Introduction

This book is the product of thirty years of close friendship and five of deliberate collaboration. Its immediate inspiration was a session we organized for the 2012 Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Music at the University of Nottingham, in honor of what we then believed was Anchieta’s 550th birthday. This is also a good time to thank our colleagues Maricarmen Gómez Muntané and Eva Esteve Roldán for their contributions and for allowing us to go our own way afterward.1 As we e-mailed back and forth in the weeks and months that followed, we began to realize that there was at least a book’s worth to say about Juan de Anchieta, and that the aspects of his work that we had been separately pursuing dovetailed nicely into what might become a more or less comprehensive introduction to his life and to the music he has left us. A scheme of alternating chapters fell into place easily, and then the hard part began.

Anchieta does not appear, as far as his surviving output goes, to have been an especially productive composer, at least in comparison with his colleague at the Aragonese chapel, Francisco de Peñalosa. But even that is relative: the loss of many polyphonic sources and the strong tradition of unwritten and semi-improvised polyphony in the Iberian Peninsula make it problematic to gauge the output of Spanish composers from this period in purely numerical terms. But Anchieta proves to be an interesting figure in the history of Spanish music, if only because, of the three most important composers of the time of Ferdinand and Isabel, he was first on the scene by a good deal, joining the Castilian royal chapel in 1489 and having already written some significant compositions by the time Peñalosa arrived at Ferdinand’s court in 1498 and long before we first catch sight of the largely mysterious Pedro de Escobar in 1507. And, in more recent centuries, both his biography and his worklist have excited a perhaps surprising level of controversy, which we will discuss more presently.

From the beginning we have conceived of this book as an old-fashioned life-and-works study, in the manner, just to choose from the recent books of some of our own friends and colleagues—of David Fallows’s studies of Dufay and Josquin,2 Rob Wegman’s of Obrecht,3 and Honey Meconi’s of La Rue.4 Such works are, of course, a time-honored tradition in musical scholarship, and if they sometimes tend to support a great-man or dead-white-male view of history—and there is no doubt that Anchieta was white and male and is now dead, and we hope to argue that he was reasonably great—we take comfort in knowing that our book will stand beside an astonishing new wealth of scholarship on women and music, on smaller institutions, and on community music in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Spain.5 Women were important in Anchieta’s career as chapel singer, teacher, and composer: he worked in turn for Isabel and her daughter Juana, was closely associated with Margaret of Austria, and at the end of his life was connected with a convent in the Basque country. His life and works thus serve as an exemplary representation of the importance of female patronage in the music of the Josquin era.

The life of a Renaissance composer is almost always obscure in its psychology and its daily details; most of their biographies still have large distressing gaps for periods from which no written records have been found at all; and virtually all, at least in the manuscript age, are written in the sad knowledge that a great deal of their music has been lost. Anchieta has, it must be said at the outset, all of these problems, and one more: both the life and the works have been further bedeviled by late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars working, however carefully and sincerely, within one unspoken agenda or another. This requires some untangling, and it is worth beginning to outline some of the problems here in the Introduction.

The worklist

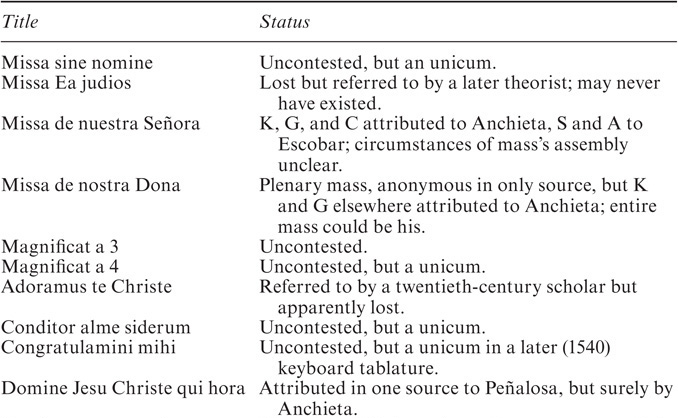

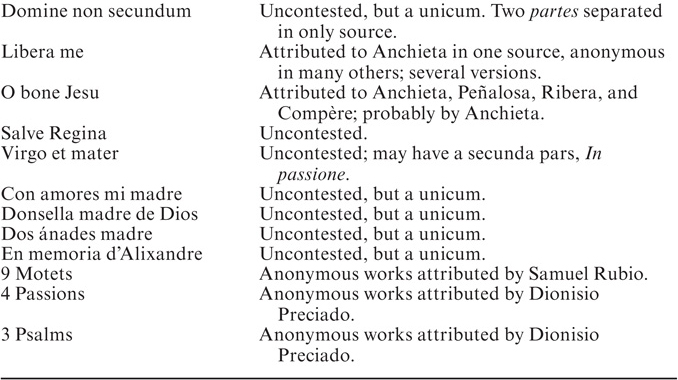

Appendix 1 at the end of the book lists all the works attributed to Anchieta somewhere, by somebody, with their sources. It may conveniently be rearranged and condensed, and the situation of each work summarized, thus (Table I.1).

To summarize further, of the thirty-five compositions on the list, by our count—

• thirteen are uncontested, but ten of these are attributed in only one source and the dimensions of one other are in question;

• two are contested in the surviving sources—one is certainly and one probably by Anchieta;

• there are two masses that are at least partly by Anchieta, one of which may be entirely his;

• two works have, if they ever existed, been lost; and

• sixteen are conjectures from twentieth-century scholars, nearly all of which we are skeptical about.

The works portion of this life-and-works, in short, is a bit of a moving target, and in talking about Anchieta’s music, we must constantly remember and reassess the level of doubt attached to individual compositions. Of particular concern are the sixteen pieces—nearly half the total, at least by title—that were assigned to Anchieta by Samuel Rubio (1912–1986) and Dionisio Preciado (1919–2007). Both of these men were highly respected scholars who knew the music of this period well, and we do not lightly discount their testimony; but both were part of a time that tended to interpret manuscript attributions as applying to more than one piece at a time, as we do not like to do today, and both, perhaps significantly, were of Basque origin and perhaps overeager to give music to their countryman. This brings us in turn to the historiography, and the nationalist motivations (among others) that lie behind it, of Anchieta’s life story as it has been told over the years.

Problems with the biography

The “life and works” study has, by nature, to be as comprehensive as possible and, ideally, to mesh biographical context with musical analysis. This in itself presents difficulties for the biographer-historian of a composer active over 500 years ago: it is particularly problematic to date works with any degree of certainty, although in the case of Anchieta, at least one song can be dated securely to 1489, and several sacred works have a terminus ante quem of c1500. The biographical study will inevitably have substantial gaps, and the surviving works may well represent only the tip of an iceberg. The inevitable tendency in historical biography toward presentation of the known facts in a chronological and linear fashion may give a false impression of a sense of completeness. A mix of the surviving facts and “fiction” in the form of hypotheses where facts are missing tends to result in a narrative strategy that might easily suggest the realistic novel.6 The temptation to fill in the gaps through surmise and hypothesis is difficult to avoid entirely, and hypotheses can build over time into a historiographical tradition from which it is difficult to disentangle fact from supposition. This has been the case with the historiographical tradition that has developed with regard to the life of Juan de Anchieta: documentary gaps have, in several respects, been filled according to prevailing issues of national identity or political and religious interests and transmuted into fact. For example, Anchieta’s biography has both benefited and suffered from his close family ties to St. Ignatius of Loyola and the hagiographical approach of some early Jesuit historians: a large amount of documentation was unearthed regarding Anchieta and his extended family, but it appears that some of it was then “lost,” presumed destroyed, as will be discussed later. Three historiographical strands can be disentangled in the narrative of his life: first, the vindication of the existence of a “national school” of Spanish composers in the early Renaissance; second, a Jesuit historiographical discourse inextricably linked with the early life of St. Ignatius of Loyola; and third, regional identification of him as a key figure in Basque cultural history.7

These competing claims of “ownership” of Anchieta as a Basque composer, a pioneer of nationalism in early Spanish music, and an eminent relative of the founder of the Jesuit Order make it difficult to find a balanced, impartial view of Anchieta’s life: Robert Stevenson’s potted account in his classic study Spanish Music in the Age of Columbus (1960) is probably as close as it gets.8 Moreover, Anchieta’s life of prestige, politics, travel, and relative wealth—not to mention the probable assassination attempt by a future saint—reads strikingly like a novel, and few of his biographers have resisted the temptation to speculate on his personal experiences and motives. In particular, two of the most extended biographies adopt what might be described as the “realistic novel” approach, imaginatively filling in gaps in the documentation: Adolphe Coster, in his 1930 essay on Anchieta and the Loyola family,9 and the relatively concise account in Juan Plazaola’s 1997 study of three distinguished personages with the surname Anchieta.10

Some of the facts relating to Anchieta’s biography passed into historiographical tradition from the late nineteenth century, at a time when the discovery of the Palace Songbook enabled Francisco Asenjo Barbieri and other early music historians to vindicate the existence of a “Spanish school” of composers which had been cast into doubt by some of the earliest generation of German and Belgian musicologists.11 In 1884, Francisco Asenjo Barbieri commissioned, at his personal expense, a biography of the composer from the Basque Jesuit Eugenio de Uriarte.12 Barbieri subsequently included the main points of this information, together with the references he had found in the state archive in Simancas, in his 1890 edition of the so-called Cancionero Musical de Palacio (known for many years as the “Cancionero de Barbieri”).13 The first modern edition of Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo’s Libro de la Cámara real del Príncipe don Juan had appeared in 1870,14 so Barbieri was also able to include the reference to Anchieta in that work in his summary.

Barbieri claimed he was the first to write a biography of Anchieta, and expressed his surprise that such an omission should have existed in the history of Spanish music.15 He lamented the lack of interest on the part of Spanish and non-Spanish music historians, which meant that no information had been published on Anchieta, and expressed his intention to remedy that need. He indicated that his own research in the Archivo General de Simancas had been supplemented by information gathered by Uriarte. He failed to mention, however, that a published biography of Anchieta had appeared in 1887, that is, between 1884 when Uriarte sent Barbieri his notes, and the publication of the edition of the Palace Songbook in 1890. This essay was attributed to the Jesuit historian José Ignacio de Arana and was published in a Basque journal.16 Javier Pino Alcón has shown that this essay, apart from minor changes, is an exact copy of Uriarte’s notes as published in Legado Barbieri.17

Barbieri appears to have been unaware of the existence of this article—or to have ignored it—and it also difficult to ascertain whether the essay appeared under Arana’s name with Uriarte’s blessing, or as unacknowledged plagiarism. Arana’s interest would have been aroused through his research on St. Ignatius of Loyola, and he contributed many articles to the Basque journal. The Uriarte/Arana text included the transcription of a number of documents relating to Anchieta’s life, notably his appointments to the ecclesiastical benefice of Villarino in 1499 and to the rectorate of the parish church of San Soreasu in Azpeitia in 1504. As will be discussed in more detail later in the first chapter, Basque writers were quick to claim Anchieta as their own at a regional level: Carmelo de Echegaray praised Barbieri’s edition and went on to defend Basque culture; who could say, he asked rhetorically, that the Basque country lacked artistic competence when there was such a brilliant array of Basque artists throughout history?18

It can thus be seen that the three narrative strands were closely interwoven from the start. The nationalist discourse continued through much of the twentieth century; in 1947, Higinio Anglés considered Anchieta to be “one of the founders of the Spanish school of composition of the time of the Catholic Monarchs,”19 a point reiterated by Samuel Rubio in the Renaissance volume of the Historia de la música española of 1983.20 The concept of the “national schools,” each with a distinctive musical style, was commonly debated in the early musicological discourse of the latter part of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth, although it is now recognized to be fraught with ideological and aesthetic problems. As Juan José Carreras has discussed, Anglés’s agenda in the first volume of the Monumentos de la Música Española was, at least in part, to confirm the existence of an indigenous musical tradition that had been deliberately cultivated by the Catholic Monarchs—an idea that found fertile soil in the political discourse of the Franco era, with its intense concern over the unification of Spain and the identity of its culture.21 Nevertheless, Barbieri-Uriarte established many of the details pertaining to Anchieta’s service in the royal chapels, and these data have been followed and occasionally expanded upon by subsequent biographers who undertook research in the royal and cathedral archives, notably Juan B. de Elústiza and Gonzalo Castrillo Hernández (1933), Higinio Anglés (1941), Robert Stevenson (1960), Mary Kay Duggan (1979), Samuel Rubio (1983), Tess Knighton (1984/2000), Pedro Aizpurúa (1995), Kenneth Kreitner (2004), and, most recently, Mary Ferer (2012).22

After Barbieri-Uriarte, the single most important contribution to the filling out of Anchieta’s biography was that of the French Hispanist Adolphe Coster (1868–1930), whose extended essay entitled “Juan de Anchieta et la famille de Loyola,” published in 1930, resulted from his study of the life of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Specifically, Coster’s interest was aroused by Anchieta’s possible role in the conversion of the young Ignatius, who the French writer also believed might well have been responsible for a vicious attack on the composer. Coster’s account was severely criticized the following year by the Jesuit historian José María Pérez Arregui, for being too hypothetical.23 Pérez Arregui’s staunch, even aggressive, defense of St. Ignatius suggests both Jesuit concerns and personal pique: his own study San Ignacio en Azpeitia had been published in 1921, and was criticized by Coster for remaining silent on the facts that were considered unacceptable in the life of the future saint.24

Coster referred to some unpublished documentation regarding Loyola and Anchieta from the municipal archive that had been drawn on by Leonardo J.-M. Cros (which Pérez Arregui claimed not to have been able to consult), and the biography of Loyola by the Italian Jesuit historian Pietro Tacchi Venturi (1922).25 The exact nature of the missing documents is impossible to ascertain, but presumably referred to the assassination attempt of 1515 and disappeared as part of an agenda in Jesuit historiography—to which Pérez Arregui contributed—to mitigate Loyola’s less than blameless early life. The most recent study of the Jesuit angle by Francisco de Borja Medina Rojas (2012) presents a more balanced and contextualized reading of the surviving documents, although it remains inconclusive. According to Borja Medina Rojas’s reassessment of the surviving documentation, there is no doubt that St. Ignatius was accused of a serious crime and had to flee to Pamplona, but the exact nature of that crime remains unclear.26

Coster based much of his biography of Anchieta on the archival work of José Adriano de Lizarralde, who, in 1921, had published a detailed account of the history of the Convent of the Most Pure Conception in Azpeitia, with which Anchieta was closely associated in the latter part of his life.27 This important information complemented the details found by Uriarte and affords much greater insight into the last years of the composer’s life and his social standing. Music historians, notably Stevenson, have generally followed Coster on the relationship between Anchieta and Loyola without reference to the Jesuit historiographical debate, which necessitates re-examination of several of the “facts” of Anchieta’s life.

As Pino Alcón has suggested, Coster’s account is heavily documented, making it appear a solid and scientific piece of research. However, in many instances, Coster presented speculation as if it were fact, in a merging of documentary evidence and his personal interpretation of it.28 Several of Coster’s errors and hypotheses thus passed into the historiography and became accepted as fact; for example, Pino Alcón demonstrates that Coster’s mistake in the identification of Anchieta’s mother has led to a false sense of security over his date of birth, generally given as 1462, when it is more likely that he was born in the 1450s.29 There is no evidence for Coster’s suggestion that Anchieta taught music to the young Ignatius, an idea taken up by some Jesuit historians, while others have sought to play down the future saint’s interest in music.30 Similarly, Coster’s hypothesis that Anchieta studied in Salamanca is given some credence by Stevenson, although both authors do point out that there is no hard evidence for this idea.31 Such reservations are cast aside by later music historians such as Dámaso García Fraile, who proudly asserts that “Juan de Anchieta, six years older than Juan del Encina, studied at Salamanca University and, like Encina, was taught by Encina’s older brother Diego de Fermoselle.”32

A generous interpretation might accuse García Fraile, himself Professor of Music at Salamanca University, of indulging in wishful thinking, and perhaps the same could be said of José Antonio Donostia’s suggestion that Anchieta began his training as a choirboy at Pamplona Cathedral.33 As mentioned earlier in this introduction, the music historiographical tradition claimed early on that Anchieta was a key figure in the development of Basque music, and Donostia’s study, like Coster’s, adds to the confusion over certain aspects of his biography, in particular, the notion that Anchieta was yearning to retire in his native Azpeitia, an idea promulgated by Coster, who imagined the composer longing to leave the court and return to his home town to show off his wealth and status.34 Coster’s speculations, in full-blown historical novel mode, quite often included allusions as to how the composer was feeling at a given moment in time. Subsequently, his attempts to fill in the gaps and add verisimilitude were taken up by those who wanted to believe those “facts” which matched their own interests and concerns. Donostia’s brief study of 1951 had been preceded by an article on Anchieta’s house in Azpeitia by the local historian Joaquín de Irizar (1947),35 and was followed by a number of other Basque writers and researchers: Enrique Jordá (1978), Imanol Elias Odriozola (1981), Jon Bagües (1993), Plazaola (1997), and Pedro Aizpurúa (1995), whose biographical profile of the composer is one of the most complete.36 With the exception of Aizpurúa, most of these authors passed over the documentation that continued to link Anchieta to Queen Juana in Tordesillas and his appointment as a member of the Aragonese royal chapel from 1512. Thus, the extent to which Anchieta resided in Azpeitia in the latter part of his career has been assumed incorrectly, and at times exaggerated.

It should perhaps be noted that not all these Basque writers were entirely complimentary about the Basque composer. Enrique Jordá, for example, painted Anchieta as an ambitious courtier, constantly seeking wealth and favor, and, with the astuteness of the master chess player, generally achieving his ends, however unethically.37 Even his donation of the Villarino benefice to the nuns of Azpeitia is seen as a calculated act designed to secure his burial there, but then who, in Jordá words, “is exempt from such failings?”38 This novelistic approach clearly derives from Anchieta’s relatively well-documented career, but projects an interpretation of it that cannot be verified. It comes as something of a relief to find a degree of balance in Donostia’s summary of Anchieta’s achievements as a composer:

Anchieta’s masses, motets, and Magnificats display fluent and correct writing, without seeking complexity for the sake of complexity. Certainly, he does not achieve the greatness of his contemporary, Josquin des Prez, yet the expressivity of his music is genuine and makes it interesting.39

In a newspaper article on St. Ignatius’s family from 1934, Donostia called for Anchieta, as the earliest known Basque composer with works to his name, to inaugurate the first volume of a projected Monumenta Polyphonica Vasconiae.40 Indeed, Donostia had prepared an edition of Anchieta’s works by the time Anglés published the first volume of La música en la corte de los Reyes Católicos in 1947,41 and he continued to find new information in the archives of Simancas and Lille, which he gathered together for an article entitled “Johanes de Anchieta y su obra musical,” which was finally included in the volume of Donostia’s oeuvre published in 1985.42 After Coster, Donostia was one of Anchieta’s most assiduous biographers, although a complete edition of Anchieta’s works did not appear until that by Rubio in 1980.

Thus, local and regional history has combined over the years with studies dedicated to the institutional history of court and church music to piece together the biography of Juan de Anchieta. The first chapter of our study brings together and reassesses the documented facts of his life and analyzes the hypotheses and disputes that have characterized the historiography stretching back over almost a century and a half. Further, it presents the information in the context of the period in which Anchieta lived, and assesses it according to what is known about prevailing practices and mentalities of around 1500. Finally, it provides a starting-point for the consideration of his music, placing his works, where possible, within the chronology of his life and in the light of the cultivation of musical genres and styles in the social and cultural milieu in which he worked.

******

The chapters in this book were written, for the most part, on separate continents and shared as drafts via e-mails: Chapters 1, 3, and 5 are by Knighton and Chapters 2, 4, and 6 by Kreitner. The Introduction and Chapter 7 were written jointly. This “conversation” has resulted in the use of first-person singular and plural as appropriate. You should consider these chapters as individual essays, though, of course, we have read each other’s drafts and commented on them extensively, and the whole book reflects a very substantial degree of collaboration and ultimate agreement on nearly every point. Early in the process, we resolved not to strain after a false uniformity: we have each tried to say what we think needs to be said about the various subjects, following the paths of our individual curiosity, and have not attempted to imitate each other’s literary style. We have aimed to make the chapters roughly equal in size and scope, though the biographical section has naturally required a good deal more space than the chapters about the music. We hope it makes sense as a coherent argument despite this division of labor.

We began this project with a conviction that Juan de Anchieta was at the very least a fascinating figure, and a suspicion that he may have been an important one. We end it, after a long look at the documentary and musical evidence, with both these beliefs amply affirmed. A few old mysteries remain, and maybe a few new ones have appeared. It does begin, however, to look as though Anchieta, more than anyone we can now see, was the man who brought the musical Renaissance to its first maturity in the Iberian Peninsula. He is well worth listening to, and we hope he will be worth reading about.

******

Our thanks go to Laura Macy, who encouraged this project from the start, and to Nick Craggs at Routledge; Dana Moss; and Jeanine Furino and Hannah Lamarre at codeMantra for seeing the production process through to tangible evidence of our efforts over the years. In addition, we thank Michael Noone and D. Bonifacio Bartolomé, archivist of Segovia cathedral, for allowing us to consult the recently discovered fragments of Anchieta’s Salve Regina, and Rosa Montalt for supplying the digitalized copy of the leaves with the part of Anchieta’s Magnificat separated at some unknown moment in the past from Tarazona 2/3 and now found in the Biblioteca de Catalunya. For various kinds of assistance in the access to and interpretation of sources, we are grateful to Pedro Aizpurúa, João Pedro d’Alvarenga, Bonnie Blackburn, Howard Mayer Brown, David Burn, María Elena Cuenca Rodríguez, David Fallows, Miguel Antonio Franco Garza, María Gembero-Ustárroz, Leofranc Holford-Strevens, the Portuguese Early Music Database, Esperanza Rodríguez, Emilio Ros-Fábregas, Nuria Torres, and Grayson Wagstaff. And for various help of a more technical nature, we are thankful to Jeffrey Dean, Scott Hines, and Mark Janello.

Finally, Ivor Bolton, Sam Bolton, and Mona Kreitner have been very patient over the long gestation of this book. We are lucky to have the families we have, and doubly lucky to have each other’s families as such good friends.

Notes

1 Professor Gómez’s paper has since been published as Maricarmen Gómez Muntané, “En memoria d’Alixandre de Juan de Anchieta en su contexto,” Revista de Musicología 37 (2014): 89–106, and we shall return to it in Chapter 5; Dr. Esteve’s paper remains unpublished, and she has graciously allowed us to incorporate some of her observations in the chapters that follow.

2 David Fallows, Dufay, The Master Musicians (London: Dent, 1982, 2/1987); idem, Josquin (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009).

3 Rob C. Wegman, Born for the Muses: The Life and Masses of Jacob Obrecht (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

4 Honey Meconi, Pierre de La Rue and Musical Life at the Habsburg-Burgundian Court (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

5 Much of this work, gratifyingly, is being accomplished by a younger generation of Spanish scholars: see, for example, Giuseppe Fiorentino, “Folia,” El origen de esquemas armónicas entre tradición oral y transmisión escrita (Kassel: Reichenberger, 2013); Ascensión Mazuela-Anguita, Artes de canto en el mundo ibérico renacentista: Difusión y usos a través del Arte de canto llano (Sevilla, 1530) de Juan Martínez (Madrid: Sociedad Española de Musicología, 2014); and various articles in Tess Knighton, ed., Companion to Music in the Age of the Catholic Monarchs (Leiden: Brill, 2017).

6 A summary of the problems of writing musical biography can be found in Jolanta T. Pekacz, “Memory, History and Meaning: Musical Biography and its Discontents,” Journal of Musicological Research 23 (2004): 39–80.

7 Some of these aspects have also been considered by Javier Pino Alcón, “Juan de Anchieta: La construcción historiográfica de un músico del Renacimiento” (undergraduate thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2015).

8 Robert Stevenson, Spanish Music in the Age of Columbus (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1960). Stevenson also wrote the entry on Anchieta for The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians of 1980.

9 Adolphe Coster, “Juan de Anchieta et la famille de Loyola,” Revue Hispanique 79 (1930): 1–322; the article also appeared as a monograph published in Paris by C. Klinksieck, 1930.

10 Juan Plazaola, Los Anchieta: El músico, el escultor, el santo (Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero, 1997).

11 For a summary of this situation, see Juan José Carreras, “Hijos de Pedrell: La historiografía musical español y sus orígenes naiconalistas, 1780–1980,” Il Saggiatore Musicale 8 (2001): 121–69; idem, “Zur Frühgeschichte der Alten Musik in Spanien,” in Camille Bork, Tobias Robert Klein, and Burkhard Meischein, eds., Ereignis und Exegese. Musikalische Interpretation: Interpretation der Musik: Festschrift für Hermann Danhuser zum 65. Geburtstag (Berlin: Edition Argus, 2011), 134–48; idem, “Problemas de la historiografía musical: El caso de Higinio Anglés y el medievalismo,” in Andrea Bombi, Juan José Carreras López, and Miguel Ángel Marín, eds., Pasados presentes: Tradiciones historiográficas en la musicología europea (1870–1930) (Valencia: Universitat de València, 2015), 19–52.

12 Stevenson, Spanish Music, 128.

13 Francisco Asenjo Barbieri, Cancionero Musical de los siglos XV y XVI (Madrid: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Francisco, 1890), 24–27. Barbieri briefly recognizes the contribution of Uriarte as regards “algunos pormenores interesantes.” Uriarte’s extensive notes, dated May 1884, formed part of the papers Barbieri left to the Biblioteca Nacional de España (MS 14020.170) on his death in 1894, and were transcribed as part of the Legado Barbieri in Emilio Casares Rodicio, ed., Francisco Asenjo Barbieri: Biografías y documentos sobre música y músicos españoles, 2 vols. (Madrid: Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales, 1994), I: 17–24.

14 J. M. Escudero de la Peña, ed., Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo: Libro de la Cámara Real del Príncipe Don Juan, e offiçios de su casa e serviçio ordinario (Madrid: Sociedad de Bibliófilos Españoles, 1870).

15 Barbieri, Cancionero musical, 24: “Sólo por la punible incuria española se puede explicar que un maestro compositor de tan gran notoriedad en su tiempo, como Anchieta, haya estado hasta ahora completamente obscurecido, sin que ningún biógrafo nacional ni extranjero haya dado noticia de su existencia. Ya voy a suplir esta falta….”

16 José Ignacio de Arana, “Euskaros ilustres: Biografía del Rdo. Johanes de Anchieta,” Euskal-Erria: Revista Bascongada 17 (1887): 12–18, 43–52; available online at: http://82.116.160.16:8080/handle/10690/67837 (accessed 25 July 2018).

17 Pino Alcón, “Juan de Anchieta,” 15–16.

18 Carmelo de Echegaray, “Euskaros ilustres: Juanes de Anchieta,” Euskal-Erria: revista bascongada 26 (1892): 69–271; available online at http://hdl.handle.net/10690/69841 (accessed 25 July 2018).

19 Higinio Anglés, ed., La música en la Corte de los Reyes Católicos, I: Polifonía religiosa, Monumentos de la Música Española 1 (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1941, 2/1960), hereafter abbreviated MME 1, 7: “Anchieta debe ser considerado como uno de los fundadores de la escuela musical española de la época de los Reyes Católicos.”

20 Samuel Rubio, Historia de la música española: Desde el “ars nova” hasta 1600 (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1983), 117–19, at 118: Rubio talks of the Spanish roots (“la típica raigambre española”) of Anchieta’s works.

21 See Note 11.

22 Juan B. de Elústiza and Gonzalo Castrillo Hernández, Antología Musical: Polifonía vocal siglos XV y XVI (Barcelona: Rafael Casulleras, 1933), xxxiii–xxxiv; Anglés, MME 1, 6–7; idem, La música en la Corte de Carlos V, Monumentos de la Música Española 2 (Barcelona: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1944, 2/1965), 4 and 14–20; Stevenson, Spanish Music, 127–45; Mary Kay Duggan, “Queen Joanna and Her Musicians,” Musica Disciplina 30 (1976): 73–95; Samuel Rubio, ed., Juan de Anchieta: Opera omnia (Guipuzcoa: Caja de Ahorros Provincial de Guipuzcoa, 1980), 13–20; Pedro Aizpurúa, “Perfil biográfico-musical,” in Dionisio Preciado, ed., Juan de Anchieta: Quatro pasiones polifónicas (Madrid: Sociedad Española de Musicología, 1995), 17–25; Tess Knighton, Música y músicos en la corte de Fernando de Aragón, 1474–1516 (Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, 2000), 323–24 (the Spanish translation, by Luis Gago, of “Music and Musicians at the Court of Fernando of Aragon [1474–1516]” [PhD diss., University of Cambridge, 1984]); Kenneth Kreitner, The Church Music of Fifteenth-Century Spain, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music 3 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2004), 104–105; and Mary Tiffany Ferer, Music and Ceremony at the Court of Charles V. The Capilla Flamenca and the Art of Political Promotion, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music 12 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2012), 35–36 and 42–43.

23 José María Pérez Arregui, “El Iñigo de Loyola visto por Adolfo Coster,” Razón y Fe 95 (1931): 324–47; Razón y Fe 96 (1931): 203–25; and Razón y Fe 97 (1932): 200–215.

24 Coster, Juan de Anchieta, 22.

25 Leonardo J.-M. Cros published a biography of Francis Xavier in 1894; and see Pietro Tacchi Venturi, Storia della Compagnia de Gesù in Italia: narrata col sussidio di fonte inedite (Roma: Società Editrice Dante Alighieri di Aghiebri Segati & C., 1910).

26 Francisco de Borja Medina Rojas, “Los delictos calificados y muy henormes de Iñigo de Loyola. Notas al llamado Proceso de Azpeitia de 1515, estudio documental,” Archivium Historicum Societatis Iesu 81, fasc.161 (2012): 3–71.

27 José Adriano de Lizarralde, Historia del Convento de la Purísima Concepción de Azpeitia. Contribución a la historia de la Cantabria francisca (Santiago: Tipografía de “El Franciscano,” 1921).

28 Pino Alcón, “Juan de Anchieta,” 23–27.

29 Ibid., 24–25; see below, Chapter 1.

30 Coster, Juan de Anchieta, 73–77; see also Luis Fernández Martín, “El hogar donde Iñigo de Loyola se hizo hombre, 1506–1517,” Archivium Historicum Societatis Iesu 49 (1980): 41–65; and Luis Fernández Martín, Los años juveniles de Iñigo de Loyola (Valladolid: Caja de Ahorros de Valladolid, 1981). Fernández Martín was followed by Pedro Aizpurúa, in his “Perfil biográfico-musical,” 24–25. Aizpurúa also contributed to the entry on Anchieta in the Diccionario de Música Española e Hispanoamericana (2002).

31 Stevenson, Spanish Music, 132.

32 Dámaso García Fraile, “La Universidad de Salamanca en la música de Occidente,” in Emilio Casares Rodicio, Ismael Fernández de la Cuesta, and José López-Calo, eds., España en la música de Occidente, 2 vols. (Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura, 1987), I: 289–92, at 291.

33 José Antonio de Donostia, Música y músicos en el País Vasco (San Sebastián: Biblioteca Vascongada de los Amigos del País, 1951), 16. This suggestion was followed by Aizpurúa, “Perfil biográfico-musical,” 18.

34 Coster, Juan de Anchieta, 134; Pino Alcón, “Juan de Anchieta,” 26.

35 Donostia, Música y músicos en el País Vasco, 16–26 and 60–63; Joaquín de Irizar, “La casa de Juan de Anchieta, el músico,” Boletín de la Real Sociedad Vascongada de Amigos del País 3 (1947): 67–81.

36 Enrique Jordá, “Vida y obra de Johannes de Anchieta,” in De canciones, danzas y músicos del País Vasco (Bilbao: La Gran Enciclopedia Vasca, 1978), 127–78; Imanol Elias Odriozola, Juan de Anchieta: Apuntes históricos (Guipúzcoa: Ediciones de la Caja de Ahorros de Guipúzcoa, 1981); Jon Bagües, “Juan de Anchieta: Estado actual de los estudios sobre su vida y obra,” Cuadernos de Sección: Música 6 (1993): 9–24; Aizpurúa, “Perfil biográfico-musical,” 17–25; Plazaola, Los Anchieta. A further strand of regional historiography links Anchieta to the history of music in Pamplona Cathedral; see Leocadio Hernández Ascunce, “Música y músicos de la Catedral de Pamplona,” Anuario Musical 22 (1967): 209–46 at 212; and José Goñi Gaztambide, La capilla musical de la Catedral de Pamplona: Desde sus orígenes hasta 1600, Música en la Catedral de Pamplona 2 (Pamplona: Catedral Metropolitana de Pamplona, 1983), 24.

37 Jordá, “Vida y obra,” 134–36.

38 Ibid., 157.

39 Donostia, Música y músicos: 16: “Las misas, motetes, magnificas de Anchieta son de una escritura fácil, correcta, que no busca la dificultad por el gusto de vencerla. No llega tal vez a la altura de un contemporáneo suyo, Josquin des Prés, ciertamente, pero el expresivismo de la música de Anchieta es de buena ley y la hace muy interesante.” The question of expressivity (in music by Spanish composers) versus complexity (of the Franco-Netherlandish composers) is another discourse that will not be entered into here, but which will become apparent in the course of the following chapters.

40 José Antonio Donostia, “La música en la parentela de San Ignacio,” Diario de Euskadi, 31 July 1934, cited in Jordá, “Vida y obra,” and Pino Alcón, “Juan de Anchieta,” 32: “el primer polifonista vasco, cuya obra nos es conocida. Antxeta es el polifonista que podía inaugurar una colección, a la que se podría darse el título de ‘Monumenta Polyphonica Vasconiae’.”

41 Anglés, MME 1, 85.

42 Jorge de Riezu, ed., Obras completas del P. Donostia, 5 vols. (Bilbao: La Gran Enciclopedia Vasca, 1983–1985), V: 203–14.