Your Z6 has several convenient direct-access buttons (such as the ISO button on the top-right panel of the camera) and a customizable Information Edit screen that appears when you press the i button. However, many adjustments and settings require a trip to the Z6’s extensive menu system, which has nearly 170 individual top-level entries and dozens of additional options tucked away in sub-menus. But under that thicket of choices is the kind of versatility that makes the Nikon Z6 one of the most customizable, tweakable, and fine-tunable cameras Nikon has ever offered. If your camera doesn’t behave in exactly the way you’d like, chances are you can make a small change in the menus that will tailor the Z6 to your needs.

However, just telling you what your options are and what they do doesn’t really give you the information you need to use your camera to its fullest. What you really want to know is why you would want to choose a particular option, and how making a particular change will help improve your photographs in a given situation. That’s a big job, and I’m going to devote three entire chapters to demystifying the Z6 menu choices for you.

This chapter will help you sort out the settings for the Playback, Photo Shooting, and Movie Shooting menus, which determine how the Z6 displays images on review, and how it uses many of its shooting features to capture photos and videos. The following chapters will focus on the Custom Settings menu (Chapter 12), and Setup, Retouch, and My Menu options (Chapter 13).

While each entry in the Z6’s menus will be summarized in Chapters 11, 12, and 13, some complex functions, such as flash and autofocus options, require longer explanations and step-by-step instructions. I included those descriptions in previous chapters and will not repeat that information.

As I’ve mentioned before, this book isn’t intended to replace the Nikon manual available for your Z6, nor have I any interest in rehashing its contents. There is, however, some unavoidable duplication between the Nikon manual and the next three chapters, because, like the Nikon manual, I’m going to explain all the key menu choices and the options you may have in using them. You should find, though, that I will give you the information you really require in a much more helpful format, with plenty of detail on why you should make some settings that are particularly cryptic. Throughout, I’ll indicate my personal setting preference for many of the entries.

I’m not going to waste a lot of space on some of the more obvious menu choices in these chapters. For example, you can probably figure out what the Format Card entry in the Setup menu does, and it has only two options: Yes and No. In this chapter, I’ll devote no more than a sentence or two to the blatantly obvious settings and concentrate on the more confusing aspects of the Z6 setup, such as automatic exposure bracketing. I’ll start with an overview of using the Z6’s menus themselves.

Anatomy of the Nikon Z6’s Menus

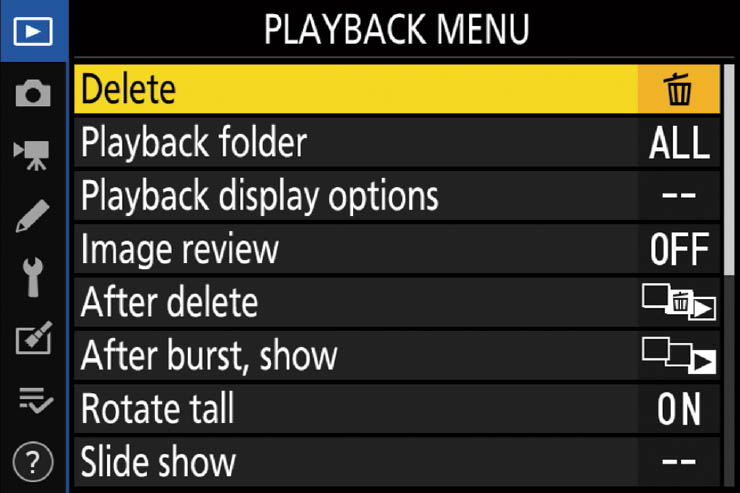

If you used any Nikon digital SLR before you purchased your Nikon Z6, you’re probably already familiar with the basic menu system. The menus consist of a series of screens with entries, as shown in the illustration of the Playback menu (discussed next) in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1 The multi selector’s navigational buttons are used to move among the various menu entries shown here.

Navigating among the various menus is easy and follows a consistent set of rules:

- View menu. Press the MENU button on the lower-right corner of the camera to display the main menu screens.

- Navigate main menu headings. Use the multi selector’s left/right/up/down buttons to navigate among the menu entries to highlight your choice. Moving the highlighting to the left column lets you scroll up and down among the seven top-level menus. From the top in Figure 11.1, they are Playback, Photo Shooting, Movie Shooting, Custom Settings, Setup, Retouch, and My Menu, with Help access (when available) represented by a question mark at the bottom of the column.

- Choose a top-level menu. A highlighted top-level menu’s icon will change from black-and-white to yellow highlighting. Use the multi selector’s right button to move into the column containing that menu’s choices. The selected top-level menu’s icon will change from yellow to a color associated with that menu (blue for Playback, green for Photo Shooting, yellow-green for Movie Shooting, red for Custom Settings, orange for Setup, purple for Retouch, and gray for My Menu). The currently selected option will be highlighted in yellow, as shown in the figure. Note: You can also press the OK button of the multi selector to move into a top-level menu’s entries, but it’s usually simpler to just press the right button, because you’ll be using the multi selector’s directional buttons to navigate the menus anyway.

- Select a menu entry. Use the up/down buttons to scroll among the entries. If more than one screen full of choices is available, a scroll bar appears at the far right of the screen, with a position slider showing the relative position of the currently highlighted entry.

- Choose options. To work with a highlighted menu entry, press the OK button, the multi selector center button, or, more conveniently, just press the right button on the multi selector. Any additional screens of choices will appear. You can move among them using the same multi selector movements.

- Confirm your choice. You can activate a selection by pressing the OK button or, frequently, by pressing the right button on the multi selector once again. Some functions require scrolling to a Done menu choice, or include an instruction to set a choice using some other button.

- Exit menus. Pressing the multi selector left button usually backs you out of the current screen, and pressing the MENU button again usually does the same thing. You can exit the menu system at any time by tapping the shutter release button.

- Returning to an entry. The Nikon Z6 “remembers” the top-level menu and specific menu entry you were using (but not any submenus) the last time the menu system was accessed, so pressing the MENU button brings you back to where you left off. So, if you were working with an entry in the Custom Settings menu’s Metering/Exposure section, then decided to take a photo, the next time you press the MENU button the Custom Settings menu and the Metering/Exposure entry will be highlighted, but not the specific submenu (b1 through b4) that you might have selected.

- Accessing a frequently used entry. If you use the same menu items over and over, you can create a My Menu listing of those entries. Or, if you’d rather have a rotating listing of the last 20 menu items you accessed, you can convert My Menu to a Recent Settings menu instead. I’ll show you exactly how to do that in Chapter 13.

Playback Menu Options

The blue-coded Playback menu, shown in Figure 11.1, has 9 entries where you select options related to the display, review, transfer, and printing of the photos you’ve taken. The choices you’ll find include the entries that follow. The last entry, Rating, is not pictured in Figure 11.1, and does not appear until you scroll the listing on the screen to the bottom.

- Delete

- Playback Folder

- Playback Display Options

- Image Review

- After Delete

- After Burst, Show

- Rotate Tall

- Slide Show

- Rating

Delete

Options: Selected, Select Date, All (default)

My preference: N/A

Choose this menu entry and you’ll be given three choices, shown in Figure 11.2, left: Selected (to choose individual images to delete); Date (to remove all photos taken on a particular day); or All (to remove all images in the folder currently selected for playback). (See Playback Folder entry, next.)

Figure 11.2 Choose selection method (left); Select individual images (right).

To select specific images or dates, follow these instructions:

- 1. Choose Selected or Date. Selection screens appear to allow you to choose which images to delete. To select by date, skip to Step 3.

- 2. Mark individual Selected images. Scroll through the thumbnails of the images displayed using the multi selector’s directional buttons. Hold down the Zoom In button to enlarge the highlighted thumbnail to full-screen view. Press the Zoom Out/Index button to mark a highlighted image for deletion, or to unmark one that has already been marked. A trash can icon is overlaid on the thumbnail when an image is marked for removal. (See Figure 11.2, right.) When finished marking, press OK to delete. Choose Yes from the Delete? screen that appears, or No to cancel.

- 3. Select dates. A list of dates on which pictures were taken appears. Press the right button to checkmark a date, or to unmark a date that has been selected. Once you’ve highlighted one or more dates, if you’re sure you want to delete all those images, press OK, and give the Z6 the go-ahead to continue on the confirmation screen that pops up.

If you want to double-check your images before removing them, press the Zoom Out/Index button to confirm your choices, and a scrollable screen of thumbnails displaying the images for the selected dates will be shown. You can press the Zoom In button to view a full-screen version of any highlighted image. When finished, press OK to return to the previous screen. Press OK again and choose Yes from the Delete All Images Taken on Selected Date screen, or No to cancel.

- 4. Exit Delete menu. To back out of the selection screens, press the MENU button.

Using this menu to delete images will have no effect on images that have been marked with an overlaid key icon when protected using the Protect option available from the i menu that appears when you press the i button during Playback. Keep in mind that deleting images in this way is slower than just wiping out the whole card with the Format command, so using Format is generally much faster than choosing Delete: All, and also is a safer way of returning your memory card to a fresh, blank state.

Playback Folder

Options: NCZ_6, All (default), Current

My preference: N/A

Your Nikon Z6 will create folders on your memory card to store the images that it creates. It assigns the first folder a number, like 100NCZ_6, and when that folder is filled, the camera automatically creates a new folder numbered one higher, such as 101NCZ_6. A folder is completely full when it contains 5,000 images, or a picture numbered 9999. If you use the same memory card in another camera, that camera will also create its own folder. Thus, you can end up with several folders on the same memory card, until you eventually reformat the card and folder creation starts anew.

This menu item allows you to choose which folders are accessed when displaying images using the Z6’s Playback facility. Your choices are as follows:

- NCZ_6. The camera will use only the folders on your memory card created by the Z6 and ignore those created by other cameras. Images in all the Z6’s folders will be displayed. This is the default setting. You can rename these folders using the Storage Folder > Rename entry in the Photo Shooting menu. Personally, I feel that the space between NCZ and 6 in the folder name is a waste of good ASCII, and will recommend some alternatives later in this chapter, using the Storage Folder entry of the Photo Shooting menu.

- All (Default). All folders containing images that the Z6 can read will be accessed, regardless of which camera created them. You might want to use this setting if you swap memory cards among several cameras and want to be able to review all the photos (especially when considering reformatting the memory card). You will be able to view images even if they were created by a non-Nikon camera if those images conform to the Design Rule for Camera File system (DCF) specifications.

- Current. The Z6 will display only images in the current folder. For example, if you have been shooting heavily at an event and have already accumulated more than 5,000 shots in one folder (or an image has been stored that’s numbered 9999) and the Z6 has created a new folder for the overflow, you’d use this setting to view only the most recent photos, which reside in the current folder. You can change the current folder to any other folder on your memory card using the Active Folder option in the Photo Shooting menu, described later in this chapter.

Playback Display Options

Options: Basic photo info: Focus Point; Additional Photo info: Exposure Info, Highlights, RGB Histogram, Shooting Data, Overview, None (Image only)

My preference: N/A

You’ll recall from Chapter 3 that a great deal of information, available on multiple screens, that can be cycled through by pressing the DISP button when reviewing images. This menu item helps you reduce/increase the clutter by specifying which information and screens will be available. To activate or deactivate an info option, scroll to that option and press the right multi selector button to add a checkmark to the box next to that item. Press the right button to unmark an item that has previously been checked. If no boxes are checked, only the default view—the image with basic information shown at the bottom of the frame—is displayed. Your additional info options include:

- Focus point. Activate this option to display the active focus point(s) with red highlighting.

- Exposure info. Shows only frame number and basic exposure information, including release mode, shutter speed, aperture, exposure compensation, and ISO sensitivity.

- Highlights. When enabled, overexposed highlight areas in your image will blink with a black border during picture review. That’s your cue to consider using exposure compensation to reduce exposure, unless a minus EV setting will cause loss of shadow detail that you want to preserve. You can read more about correcting exposure in Chapter 4.

- RGB histogram. Displays both luminance (brightness) and RGB histograms on a screen that can be displayed using the up/down multi selector buttons, as shown in Chapter 3. I explained the use of histograms in Chapter 4.

- Shooting Data. Activates the pages of shooting data shown in Chapter 3.

- Overview. Activates the overview screen shown in Chapter 3. You must scroll down the list to access this option.

- None. A screen with the image only and no photo information will be displayed.

Image Review

Options: On, On (Monitor only), Off (default)

My preference: N/A

There are certain shooting situations in which it’s useful to have the picture you’ve just shot pop up on the monitor automatically for review. Perhaps you’re fine-tuning exposure or autofocus and want to be able to see whether your most recent image is acceptable. Or, maybe you’re the nervous type and just want confirmation that you actually took a picture. Instant review has saved my bacon a few times when I accidentally made an inappropriate setting (such as specifying ISO 25600 when it really wasn’t needed or desirable).

A lot of the time, however, it’s a better idea to not automatically review your shots to conserve battery power (the LCD monitor and EVF are two of the major juice drains in the camera) or to speed up or simplify operations. For example, if you’ve just fired off a burst of eight shots during a football game, do you really need to have every frame display as the camera clears its buffer and stores the photos on your memory card? This menu operation allows you to choose which mode to use. You can elect to have the review image always appear, appear on the LCD monitor only, or never appear. Unfortunately, Nikon neglected to give us an On (Viewfinder Only) option for image review, but I’m going to give you several workarounds.

- On. Image review is automatic after every shot is taken, and your image will appear in the viewfinder or on the LCD monitor (depending on which you are using).

- On (Monitor only). Image review is displayed only on the rear-panel LCD monitor, and then only if you are not currently looking through the viewfinder; to see image review, move the camera away from your eye.

- Off. Images are displayed only when you press the Playback button. Nikon, in its wisdom, has made this the default setting.

When I am shooting concerts and performances where the audience area is darkened, I don’t want the LCD monitor lighting up after every shot and annoying people. Even so, I may want to review my images and would like them to appear immediately—just not on the monitor. There are several ways to activate that behavior.

- If you select ON with this menu entry, if your Limit Monitor Mode Selection option (in the Setup menu, and described in Chapter 13) is set to activate Automatic Selection, as long as you keep your eye up to the viewfinder, the image preview will not appear on the monitor.

- A better choice is to disable Automatic Selection, and enable just Viewfinder Only or Monitor Only options. Then you can manually toggle between the viewfinder and monitor using the VF/Monitor button on the left side of the Z6’s pentaprism. Your image review will appear only on the currently selected screen.

- If you absolutely want to prevent having your image review appear on the monitor, visit the Limit Monitor Mode Selection entry and disable everything but Viewfinder Only.

- A compromise is to use the Monitor Brightness entry in the Setup menu and set Manual Brightness to –5. This produces a very dark screen, which is unlikely to annoy those around you. It also makes it difficult to judge exposure from the monitor alone. (That’s what the histogram is for!)

After Delete

Options: Show Next (default), Show Previous, Continue as Before

My preference: Show Next

When you’ve deleted an image, you probably will want to do one of three things: have the Z6 display the next picture (in the order shot); show the previous picture; or show either the next or previous picture, depending on which way you were scrolling during picture review. Your Z6 lets you select which action to take:

- Show next. It’s likely that you’ll want to look at the picture taken after the one you just deleted, so Nikon makes this the default action.

- Show previous. I use this setting a lot when shooting sports with a continuous shooting setting. After the sequence is taken, I press the Playback button to see the last picture in the series and sometimes discover that the whole sequence missed the boat. I sometimes go ahead and press the Trash button twice to delete the offending image, then continue moving backward to delete the five or six or eleven other pictures in the wasted sequence. You’ll often find yourself with time on your hands at football games, and feel the urge to delete a stinker series of shots to save your time reviewing back at the computer (plus freeing up a little space on your card).

- Continue as before. This setting makes a lot of sense: if you were scrolling backward or forward and deleting photos as you go, you might want to continue in the same direction weeding out bad shots. Use this setting to set your Nikon Z6 to behave that way.

After Burst, Show

Options: First Image in Burst, Last Image in Burst (default)

My preference: Last Image in Burst

This menu choice allows you to determine which image is shown after a continuous series of shots are captured, when Image Review is turned off. In practice, the Z6 will not display any images on the LCD monitor while you are shooting a burst, allowing the camera to capture frames and store them on your memory card at maximum speed. However, when the burst is complete, one image will then be shown on the screen—either the first image of the series or the last image captured. I prefer to view the final image; if it’s okay in terms of exposure and focus, I can assume the others in the series are similar, and move on to initiate another burst immediately if I want. Select First Image in Burst, instead, if you want to see the initial shot and then, perhaps, continue checking subsequent photos.

Rotate Tall

Options: On (default), Off

My preference: Off

When you rotate the Z6 to photograph vertical subjects in portrait (tall), rather than landscape (wide) orientation, you probably don’t want to view them tilted onto their sides later, either on the camera monitor and viewfinder or within your image viewing/editing application on your computer. The Z6 has a directional sensor built in that can detect whether the camera was rotated when the photo was taken and hide this information in the image file itself.

The orientation data is applied in two different ways. It can be used by the Z6 to automatically rotate images when they are displayed on the camera’s monitor and viewfinder (when On is enabled), or you can ignore the data and let the images display in non-rotated fashion when Off is selected (so you have to rotate the camera to view them in their proper orientation). As mentioned earlier, your image-editing application can also use the embedded file data to automatically rotate images on your computer screen.

This menu choice deals only with whether the image should be rotated when displayed on the camera LCD monitor or in the electronic viewfinder. (If you de-activate this option, your image-editing software can still read the embedded rotation data and properly display your images.) When Rotate Tall is turned off, the Nikon Z6 does not rotate pictures taken in vertical orientation. The image is large on your display, but you must rotate the camera to view it upright.

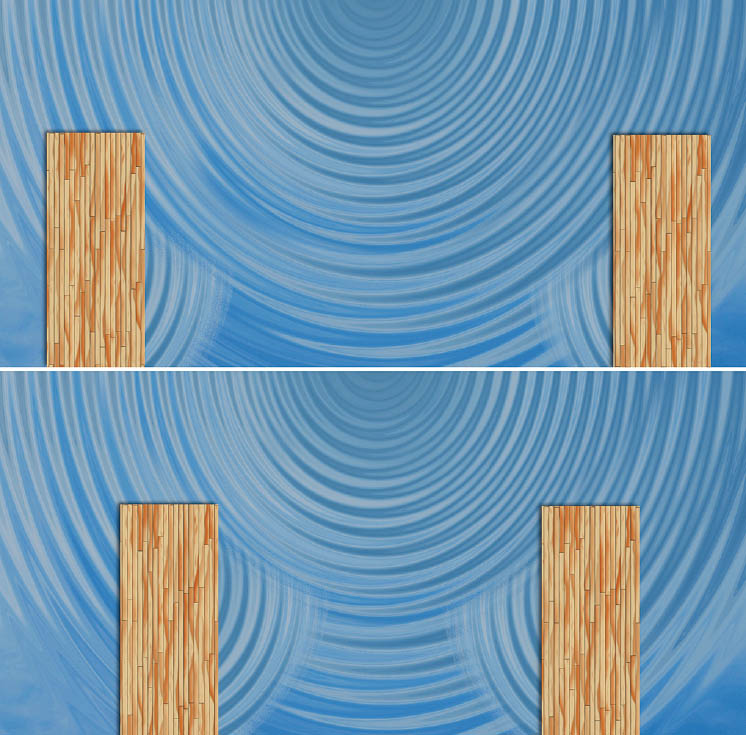

When Rotate Tall is turned on, the Z6 rotates pictures taken in vertical orientation on the monitor screen so you don’t have to turn the camera to view them comfortably. However, this orientation also means that the longest dimension of the image is shown using the shortest dimension of the monitor, so the picture is reduced in size (see Figure 11.3).

Figure 11.3 Rotate Tall: Off (top); Rotate Tall: On (bottom).

So, turn this feature On if you’d rather not turn your camera to view vertical shots in their natural orientation, and don’t mind the smaller image. Turn the feature Off if, as I do, you’d rather see a larger image and are willing to rotate the camera to do so. Rotating the camera is no big deal, and worth the trouble in order to see the largest possible review image on the display.

Slide Show

Options: Start; Image Type: Still Images and Movies (default), Still Images Only, Movies Only, By Rating; Frame Interval: 2 (default), 3, 5, 10 seconds

My preference: N/A

The Z6’s Slide Show feature is a convenient way to review images in the current playback folder one after another, without the need to manually switch between them. Re-direct the output of your camera’s video to an HDTV television, and you’ve got an instant camera-based large-screen audiovisual extravaganza. Your options include:

- Start. To activate a slide show, just choose Start from this entry in the Playback menu. During playback, you can press the OK button to pause the “slide show.” When the show is paused, a menu pops up with choices to restart the show (by pressing the OK button again), change the interval between frames, or to exit the show entirely.

- Image Type. You can choose to display both still images and movies, still images only, movies only, or images with one to five Rating stars (or none at all). The Ratings feature means you can award a “star” value to images as you shoot, or at any later time, and then activate a slide show that displays only the images with a particular rating—or images with several ratings, say, both five-star and four-star photos. I’ll explain Ratings in the next section. The default value is both stills and movies.

- Frame Interval. If you like, you can choose Frame Interval before commencing the show in order to select an interval of 2, 3, 5, or 10 seconds between “slides.” The default value is 2 seconds.

As the images are displayed, press the up/down multi selector buttons to change the amount of information presented on the screen with each image. For example, you might want to review a set of images and the settings used to shoot them. During the show:

- Change information. At any time during the show, press the up/down buttons until the informational screen you want is overlaid on the images.

- Manually change frames. As the slide show progresses, you can press the left/right multi selector buttons to move back to a previous frame or jump ahead to the next one. The slide show will then proceed as before.

- Pause. Press the OK button. Highlight Restart and press OK again to resume.

- Change playback volume (for movie images only). Press the Zoom In button to increase volume, or Zoom Out to decrease.

- Exit to Playback menu. Press the MENU button to exit the slide show and return to the Playback menu. Use this option when you want to change slide show parameters.

- Exit to Playback mode. Returns to previous playback mode (full frame or thumbnail).

- Exit to Shooting mode. Tap the shutter release button.

- Restart/Adjust. At the end of the slide show, as when you’ve paused it, you’ll be offered the choice of restarting the sequence, changing the frame interval, or exiting the Slide Show feature completely.

Rating

Options: Zero to five stars

My preference: N/A

The Rating option allows applying a star rating from zero to five stars for individual images. I love this feature, and not because my work is so variable that my images customarily range in quality from zero-star stinkers to five-star exhibition-worthy shots. In practice, you can use the Rating system to categorize your photos any way you choose, using a variety of parameters.

Select this menu item and the image selection window will appear. You can use the left/right directional buttons or touch screen to scroll among your images to highlight one you want to rate. To view a highlighted image full frame, press and hold the Zoom In button. Rate a highlighted image using the up/down buttons to apply a rating from zero to five stars, or tap the thumbnail on the monitor display one to five times. Press the down button to decrement stars, or to select the Trash icon to mark the picture for later deletion. Ratings cannot be applied to protected images. Press OK or tap Return to confirm and exit.

Images can also be rated during playback. When an image is shown on the screen as you review it, press the i button to show playback options (Rating, Select to Send to Smart Device/Deselect, Retouch, Choose Folder). Select Rating, and then use the controls to apply a rating as described above. Press OK or tap Return to confirm and exit.

I’m keen on the Rating feature because this capability is much more versatile than you might think. The stars don’t have to relate to relative image quality. You can invent any other “code” you might like to apply. For example, if you like, one star can represent photos containing animals; two stars pictures with family members; three stars photos of landscapes; and so forth. Then, with the ratings applied, you can quickly access particular types of pictures.

Or, you could mark your photos to create five different slide shows (as described earlier) on a single memory card. On a lengthy European vacation, you could assign your best shots in Spain a single star; designate shots in France with two stars; those in Italy with three; Greece, four; and Germany, five stars. Then, choose By Rating as your Image Type for your Slide Show, and then activate a show using only images with a particular number of stars. Or, you could specify a show with, say, only one-star and three-star images to display a series of Spain and Italy photographs.

Photo Shooting Menu Options

The i menu allows you to make many of the most common adjustments, including image quality, image size, autofocus mode, white balance, AF mode, and flash settings, and can be customized to include other entries of your choice. You’ll find some of these settings duplicated in the Photo Shooting menu (the first page of which is shown in Figure 11.4), along with options that you access second-most frequently when you’re using your Nikon Z6, such as specifying noise reduction for long exposures or high ISO settings. You might make such adjustments as you begin a shooting session, or when you move from one type of subject to another. Nikon makes accessing these changes very easy.

Figure 11.4 Common shooting settings can be changed in the Photo Shooting menu.

This section explains the options of the Photo Shooting menu and how to use them. The options you’ll find in these green-coded menus include:

- Reset Photo Shooting Menu

- Storage Folder

- File Naming

- Choose Image Area

- Image Quality

- Image Size

- NEF (RAW) Recording

- ISO Sensitivity Settings

- White Balance

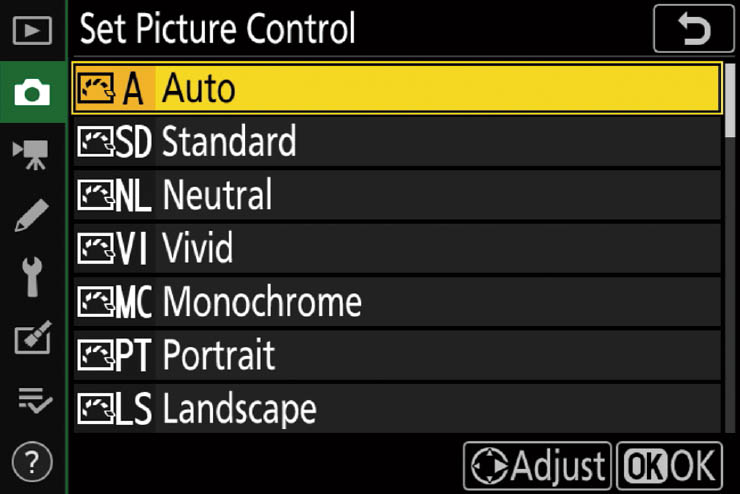

- Set Picture Control

- Manage Picture Control

- Color Space

- Active D-Lighting

- Long Exposure NR

- High ISO NR

- Vignette Control

- Diffraction Compensation

- Auto Distortion Control

- Flicker Reduction Shooting

- Metering

- Flash Control

- Flash Mode

- Flash Compensation

- Focus Mode

- AF-Area Mode

- Vibration Reduction

- Auto Bracketing

- Multiple Exposure

- HDR (High Dynamic Range)

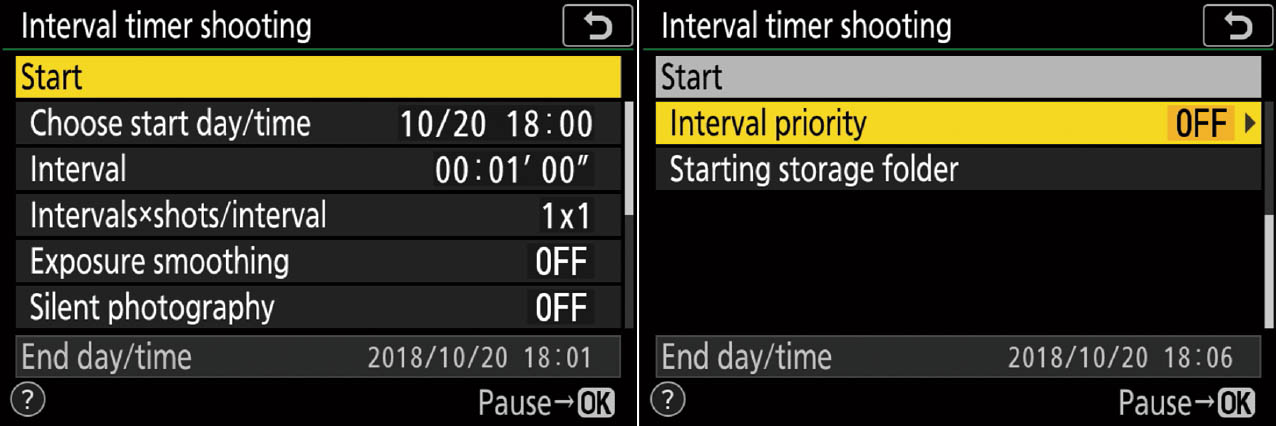

- Interval Timer Shooting

- Time-lapse Movie

- Focus Shift Shooting

- Silent Photography

Reset Photo Shooting Menu

Options: Yes, No

My preference: N/A

The Nikon Z6 has, in effect, four different kinds of resets. This is one of them.

- Photo Shooting menu reset. Use this option to reset the values of the current Photo Shooting menu to the values shown in Table 11.1.

- Movie Shooting menu reset. The Movie Shooting menu has its own settings, which are reset separately, as described later in this chapter.

- Custom Settings menu reset. This option, which I’ll describe in Chapter 12, is used to reset the Custom Settings entries. It has no effect on camera settings or Photo Shooting menu banks.

- Setup menu reset. This option resets all settings except for Language and Time Zone/Date to their default values. Use this option with caution, as it even erases copyright information and your user settings (described in Chapter 13). In that chapter I’ll also show you how to save/load settings so you can retrieve settings you saved, even after you’ve used the Setup menu reset.

Table 11.1 shows the default values that are set using Reset Photo Shooting Menu. If you don’t know what some of these settings are, I’ll explain them later in this section.

Storage Folder

Options: Rename: NCZ_6 (default); Select Folder by Number: 100 (default); Select Folder from List

My preference: I use the Select Folder by Number option frequently to organize images by topic or time frame.

If you want to store images in a folder other than the one most recently created and selected by the Nikon Z6, you can switch among available folders on your memory card, or create your own folder. Remember that any folders you create will be deleted when you reformat your memory card.

Why create your own folders? Perhaps you’re traveling and have a high-capacity memory card and want to store the images for each day (or for each city that you visit) in a separate folder. Maybe you’d like to separate those wedding photos you snapped at the ceremony from those taken at the reception. As I mentioned earlier, the Nikon Z6 automatically creates a folder on a newly formatted memory card with a name like 100NCZ_6, and when it fills with 5,000 images (an increase from the limitation of 999 images in most previous Nikon cameras) or a picture numbered 9999, it will automatically create a new folder with a number incremented by one (such as 101NCZ_6).

Folders are always identified using a three-digit number, followed by a five-character folder name. Although the default characters are NCZ_6, you can specify a name of your choice. To create your own folder or select an existing folder:

- 1. Access active folder entry. Choose Storage Folder in the Photo Shooting menu, and press the right multi selector button. The screen shown at left in Figure 11.5 appears.

- 2. Choose function. Three options are listed: Rename, Select Folder by Number, and Select Folder from List.

- Rename. Highlight and select Rename and you’ll be taken to a screen similar to the one shown at right in Figure 11.5, but with only five spaces to enter information for the naming scheme. Only numbers from 0 to 9, uppercase alpha characters, and an underline can be selected. Note that you can only change the name of your folder scheme—existing folders cannot be renamed. I like to name my folders using the scheme “NIKZ6.” It does not provide any extra information beyond that of the default “NCZ_6,” but it does make it very easy to differentiate between photos taken with my Z6, and those taken by another Z6 (most likely another photographer). See the next section, “Entering Text on the Nikon Z6” for a primer on using the on-screen keyboard.

- Select Folder by Number. If you’ve chosen this option, a screen appears with three digits representing the possible folder numbers from 100 to 999. (See Figure 11.6.) Use the left/right multi selector buttons to move between the digits, and the up/down buttons to increase or decrease the value of the digit. If a folder already exists with the number you dial in, an icon appears showing the folder is empty, partially full, or it has 5,000 images or a picture numbered 9999 (and can contain no more images).

Press OK to create the new folder and make it the active folder. You’d want to use this option to create a new folder or when you don’t know whether a folder by a particular number already exists. If a folder with that number already resides on the memory card, you can use it (if it is not full); if it doesn’t exist, you can create it.

- Select Folder from List. From among the available folders shown, scroll to the one that you want to become active for image storage and playback. This feature is handy when you want to display a slide show located in a particular folder. Use this option if you know that the folder you want to use already resides on the memory card. Press OK to confirm your choice and make the folder active.

Figure 11.5 Change your folder naming scheme, create a new folder, or select an existing folder number.

Figure 11.6 Select a folder by number.

- 3. Exit menus. Press the MENU button or tap the shutter release to exit.

Entering Text on the Nikon Z6

Your Z6 offers several opportunities to enter text, so you can change folder names, insert your name as “Artist” or provide copyright information. The Nikon Z6 uses a fairly standardized text-entry screen to name files, rename Picture Controls, create new folder names, and enter image comments and other text. You’ll be using text entry with other functions that I’ll describe later in this book. The screen looks like the one shown earlier in Figure 11.5, right, with some variations (for example, some functions have a less diverse character set, or offer more or fewer spaces for your entries). To enter text, just use the touch screen to “type” your characters or, alternatively, use the multi selector navigational buttons to scroll around within the array of alphanumerics. (I invariably use the touch screen for this, unless I am outdoors, wearing gloves, and really, really need to enter text.)

- Highlight a character. Use the touch screen or multi selector keys to scroll around within the array of characters.

- Insert highlighted character. Tap the character or press the multi selector OK button to insert the highlighted character. The cursor will move one place to the right to accept the next character.

- Non-destructively move forward/backspace. Use the main command dial to move the cursor within the line of characters you’ve entered. This allows you to skip ahead or backspace and replace a character without disturbing the others you’ve entered. Although it’s a bit more difficult for the ham-handed, you can also tap the left/right triangles on the screen located to the immediate left of the text entry area to move the cursor.

- Erase a highlighted character. To remove a character you’ve already input, move the cursor to highlight that character, and then press the Trash button or tap the trash can icon at the bottom of the screen.

- Confirm your entry. When you’re finished entering text, press the Zoom In button to confirm your entry, then press the MENU button to return to the Photo Shooting menu, or twice (or just tap the shutter release) to exit the menu system entirely.

File Naming

Options: Choose three-letter prefix. Default: DSC

My preference: NZ6

The Nikon Z6, like other cameras in the Nikon product line, automatically applies a name like _DSC0001.jpg or DSC_0001.nef to your image files as they are created. You can use this menu option to change the names applied to your photos, but only within certain strict limitations. In practice, you can change only three of the eight characters, the DSC portion of the file name. The other five are mandated either by the Design Rule for Camera File System (DCF) specification that all digital camera makers adhere to or to industry conventions.

DCF limits file names created by conforming digital cameras to a maximum of eight characters, plus a three-character extension (such as .jpg, .nef, or .wav in the case of audio files) that represents the format of the file. The eight-plus-three (usually called 8.3) length limitation dates back to an evil and frustrating computer operating system that we older photographers would like to forget (its initials are D.O.S.), but which, unhappily, lives on as the wraith of a file-naming convention.

Of the eight available characters, four are used to represent, in a general sense, the type of camera used to create the image. By convention, one of those characters is an underline, placed in the first position (as in _DSCxxxx.xxx) when the image uses the Adobe RGB color space (more on color spaces later), and in the fourth position (as in DSC_xxxx.xxx) for sRGB and RAW (NEF) files. That leaves just three characters for the manufacturer (and you) to use. Nikon, Sony, and some other vendors use DSC (which may or may not stand for Digital Still Camera, depending on who you ask), while Canon prefers IMG. The remaining four characters are used for numbers from 0000 to 9999, which is why your Z6 “rolls over” to DSC_0000 again when the 9999-number limitation is reached.

When you select File Naming in the Photo Shooting menu, you’ll be shown the current settings for both sRGB (and RAW) and Adobe RGB. Press the right multi selector button, and you’ll be taken to the (mostly) standard Nikon text entry screen described above and allowed to change the DSC value to something else. In this version of the text entry screen, however, only the numbers from 0 to 9 and characters A–Z are available; the file name cannot contain other characters. As always, press the Zoom In button to confirm your new setting.

Because the default DSC characters don’t tell you much, don’t hesitate to change them to something else. I use NZ6 for my Z6 and 850 for my Nikon D850. If you don’t need to differentiate between different camera models, you can change the three characters to anything else that suits your purposes, including your initials (DDB_ or JFK_, for example), or even customize for particular shooting sessions (EUR_, GER_, FRA_, and JAP_ when taking vacation trips). You can also use the file name flexibility to partially overcome the 9999-numbering limitation. You could, for example, use the template Z61_ to represent the first 10,000 pictures you take with your Z6, and then Z62_ for the next 10,000, and Z63_ for the 10,000 after that.

That’s assuming you don’t rename your image files in your computer. In a way, file naming verges on a moot consideration, because they apply only to the images as they exist in your camera. After (or during) transfer to your computer, you can change the names to anything you want, completely disregarding the 8.3 limitations (although it’s a good idea to retain the default extensions). If you shot an image file named DSC_4832.jpg in your camera, you could change it to Paris_EiffelTower_32.jpg later. Indeed, virtually all photo transfer programs allow you to specify a template and rename your photos as they are moved or copied to your computer from your camera or memory card.

I usually don’t go to that bother (I generally don’t use transfer software; I just drag and drop images from my memory card to folders I have set up), but renaming can be useful for those willing to take the time to do it.

Choose Image Area

Options: FX (36 × 24) (default); DX (24 × 16); 1:1 (24 × 24); 16:9 (36 × 20)

My preference: FX (36 × 24)

Here you can specify how the Z6 uses the available image area:

- Choose Image Area. You can manually specify the image area to be used, which the Z6 will apply regardless of what type of lens is mounted on the camera. Use this option to force the image area issue (as when you’re using a DX-format lens that the Z6 can’t detect automatically), or to use a particular image area for all your shots in a session. Your choices include:

- FX format (36 × 24). This is the full FX image format area, roughly 36mm × 24mm, producing a 24 MP image when Large is selected using the Image Size entry described shortly.

- DX format (24 × 16). This fills the image frame with the image in the center 24mm × 16mm of the sensor, creating a 1.5X crop factor. (See Chapter 7 for more about the crop factor and lenses.) Your final image will be about 19.5 MP.

- 1:1 (24 × 24). An image cropped to a square may be useful to emphasize a centered image, such as a close-up of a flower, when you want to direct the eye to the middle of the frame, rather than have it roam around within your image. The resulting 30 MP photo still has outstanding resolution even though you’re discarding pixels at left and right of the frame.

- 16:9 (36 × 20). This is a useful cropping that allows you to take still photos using the same 16:9 proportions as a high-definition movie frame. I like this crop when I’m producing storyboards for video productions, as my still image compositions will match the aspect ratio of the movies.

Image Quality

Options: NEF (RAW)+JPEG (Fine*, Fine, Normal*, Normal, Basic*, Basic), NEF (RAW), JPEG (Fine*, Fine, Normal*, Normal [default], Basic*, Basic), TIFF (RGB)

My preference: NEF (RAW)+JPEG Fine* for everyday shooting; JPEG Fine* for sports

As I noted in Chapter 3, you can choose the image quality settings used by the Z6 to store its files. You can use this menu entry, or, opt for the quickest way by pressing the i button, selecting the Image Quality entry (by default the second from the left in the top row), and either rotating the command dial or pressing the OK button to select quality from a screen of choices.

You can choose NEF (RAW) (only), NEF+ six different JPEG quality levels (Fine*, Fine, Normal*, Normal, Basic*, and Basic), or any of those six JPEG quality levels alone (with no NEF captured). TIFF (RGB) is also available. When you elect to store only JPEG versions of the images you shoot, you can save memory card space as you bypass the larger RAW files. Or, you can save your photos as RAW files, which consume more than twice as much space on your memory card. Or, you can store both at once as you shoot.

Many photographers choose to save both JPEG and a RAW, so they’ll have a JPEG version that might be usable as is, as well as the original “digital negative” RAW file in case they want to do some processing of the image later. You’ll end up with two different versions of the same file: one with a .jpg extension, and one with the .nef extension that signifies a Nikon RAW file.

To choose the combination you want using the menu system, access the Photo Shooting menu, scroll to Image Quality, and select it. Screens similar to the ones shown in Figure 11.7 (left and right) will appear. Scroll to highlight the setting you want, and either press OK or push the multi selector right button to confirm your selection.

In practice, you’ll probably use the JPEG Fine* and RAW+JPEG Fine* (with the “extra quality” star) selections most often. Why so many choices, then? There are some limited advantages to using some of the higher compression and lower resolution options. Settings that are less than max allow stretching the capacity of your memory card so you can shoehorn quite a few more pictures onto a single memory card. That can come in useful when on vacation and you’re running out of storage, or when you’re shooting non-critical work that doesn’t require 24 megapixels of resolution (such as photos taken for real estate listings, web page display, photo ID cards, or similar applications). Some photographers like to record RAW+JPEG Basic so they’ll have a moderate-quality JPEG file for review only and no intention of using for editing purposes, while retaining access to the original full-resolution/uncompressed RAW file for serious editing.

Figure 11.7 You can choose RAW, JPEG, or RAW+JPEG formats here.

For most work, using lower resolution and extra compression is false economy. You never know when you might need that extra bit of picture detail. Your best bet is to have enough memory cards to handle all the shooting you want to do until you have the chance to transfer your photos to your computer or a personal storage device.

TIFF (RGB)

The TIFF format is a lossless uncompressed 8-bit format (at least, in its Nikon incarnation) that is preferred for some applications, such as stock photography. TIFFs are several times larger than RAW files, more than 60MB each when shot using the Large image size. And it takes a long time to store a TIFF file on a memory card (a second or two, at least), so most photographers don’t create TIFFs in the camera. It’s often a better idea to produce a TIFF file from a RAW file, because RAW/NEF files can contain up to 14 bits of information with potentially a wider range of colors captured. Nikon’s TIFF format files are reduced from the 12-bit or 14-bit image captured by the sensor to just 8 bits of information per color channel. One key advantage of capturing TIFF in the camera is that the file is noncompressed, with minimal camera processing, giving you the best ready-to-use image quality outside of a RAW file.

Optimal Quality or Optimal Size?

Nikon has merged the JPEG-oriented “Optimal Quality” and “Optimum Size” options offered with previous cameras into the Image Quality entry. The difference:

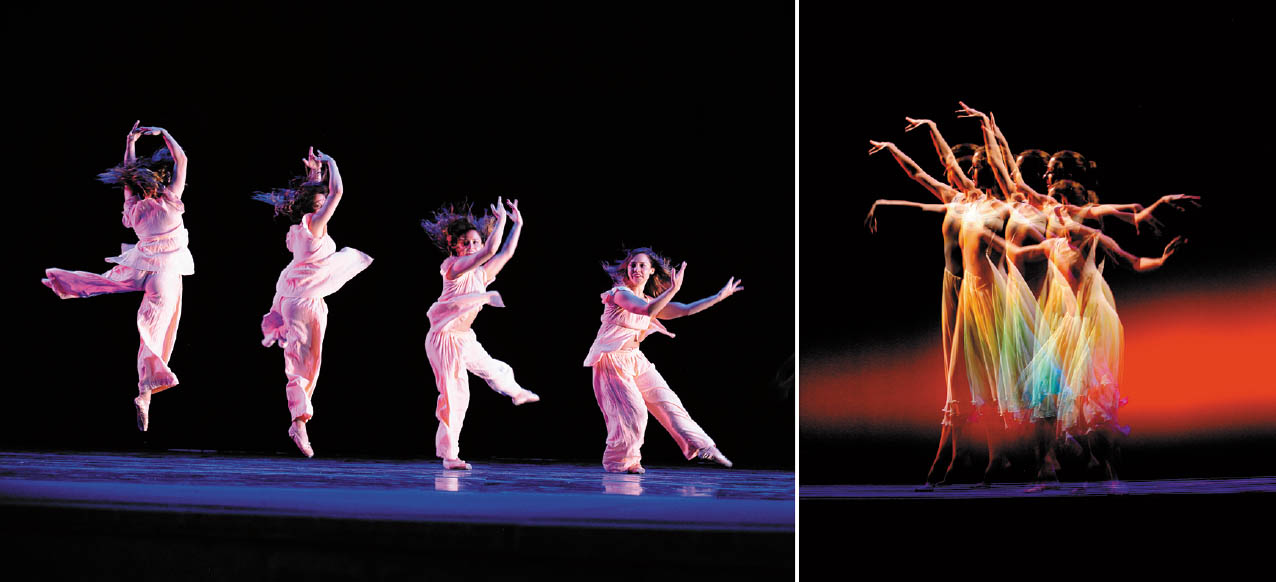

- Optimal Quality (marked with a star). Choose this option if you want to maintain the best image quality possible at a particular JPEG setting and don’t care if the file size varies. Because the Z6 will use only the minimum amount of compression required at each JPEG setting, file size will vary depending on scene content, and your buffer may hold fewer images during continuous shooting. If you’re not shooting continuously, this setting will provide optimum image quality. Figure 11.8 shows a cropped portion of an image recorded with Optimal Quality (top) and one in which Size Priority was used to provide extra compression (bottom).

- Size Priority (no star). When this option is selected, the Z6 will create files that are fairly uniformly sized JPEG images. Because some photos have content that is more easily compressible (for example, plain areas of sky can be squeezed down more than areas filled with detail), to maintain the standard file size the camera must apply more compression to some images, and less to others. As a result, there may be a barely noticeable loss of detail in the more heavily compressed images. The uniform file size also means that the Z6’s buffer will hold the maximum number of shots during continuous shooting, allowing you to shoot longer sequences without the need to pause and wait for some images to be written to the memory card. In practice, you may find you can shoot continuously until the memory card fills.

Figure 11.8 At low levels of JPEG compression, the image looks sharp even when you enlarge it enough to see the actual pixels (top); when using extreme JPEG compression (bottom), an image obviously loses quality.

JPEG vs. RAW

You’ll sometimes be told that RAW files are the “unprocessed” image information your camera produces, before it’s been modified. That’s nonsense. RAW files are no more unprocessed than your camera film is after it’s been through the chemicals to produce a negative or transparency. A lot can happen in the developer that can affect the quality of a film image—positively and negatively—and, similarly, your digital image undergoes a significant amount of processing before it is saved as a RAW file. Nikon even applies a name (EXPEED 6) to the digital image processing (DIP) chip used to perform this magic.

A RAW file is more similar to a film camera’s processed negative. It contains all the information, captured in 12-bit or 14-bit channels per color (and stored in a 16-bit space), with no sharpening and no application of any special filters or other settings you might have specified when you took the picture. Those settings are stored with the RAW file so they can be applied when the image is converted to a form compatible with your favorite image editor. However, using RAW conversion software such as Adobe Camera Raw or Nikon Capture NX-D, you can override those settings and apply settings of your own. You can select essentially the same changes there that you might have specified in your camera’s picture-taking options.

RAW exists because sometimes we want to have access to all the information captured by the camera, before the camera’s internal logic has processed it and converted the image to a standard file format. Even Compressed RAW doesn’t save as much space as JPEG. What it does do is preserve all the information captured by your camera after it’s been converted from analog to digital form.

So, why don’t we always use RAW? Some photographers avoid using Nikon’s RAW NEF files on the misguided conviction that they don’t want to spend time in post-processing, forgetting that, if the camera settings you would have used for JPEG are correct, each RAW image’s default attributes will use those settings and the RAW image will not need much manipulation. Post-processing in such cases is optional, and overwhelmingly helpful when an image needs to be fine-tuned.

Although some photographers do save only in RAW format, it’s more common (and frequently more convenient) to use RAW plus one of the JPEG options, or, if you’re confident about your settings, just shoot JPEG and eschew RAW altogether. In some situations, working with a RAW file can slow you down a little. RAW images take longer to store on the memory card, and must be converted from RAW to a format your image editor can handle, whether you elect to go with the default settings in force when the picture was taken, or make minor adjustments to the settings you specified in the camera.

As a result, those who depend on speedy access to images or who shoot large numbers of photos at once may prefer JPEG over RAW. Wedding photographers, for example, might expose several thousand photos during a bridal affair and offer hundreds to clients as electronic proofs for inclusion in an album. Wedding shooters take the time to make sure that their in-camera settings are correct, minimizing the need to post-process photos after the event. Given that their JPEGs are so good, there is little need to get bogged down shooting RAW.

Sports photographers also avoid RAW files. I recently photographed an air show that was an all-day affair, and, to make sure I didn’t miss any peak moments as the aircraft flyovers, military sky-divers, and other action unfolded, I set my camera at the maximum rate and fired away. I managed to shoot 7,200 photos in a single day. I certainly didn’t have any plans to do post-processing on very many of those shots, so carefully exposed and precisely focused JPEG images were my file format of choice that day.

JPEG was invented as a more compact file format that can store most of the information in a digital image, but in a much smaller size. JPEG predates most digital SLRs and was initially used to squeeze down files for transmission over slow dial-up connections. Even if you were using an early dSLR with 1.3 MP files for news photography, you didn’t want to send them back to the office over the telephone line communications that were common before high-speed Internet links became dominant.

HIDDEN JPEGS

You may not be aware that your RAW file contains an embedded JPEG file, hidden inside in the JPEG Basic format. It’s used to provide thumbnail previews of JPEG files, which is why you may notice an interesting phenomenon when loading a RAW image into a program like Nikon Capture NX or Adobe Lightroom. When the software first starts interpreting the RAW image, it may immediately display this hidden JPEG view which has, as you might expect, all the settings applied that you dialed into the camera. Then, as it finishes loading the RAW file, the application (Lightroom in particular) uses its own intelligence to fine-tune the image and display what it thinks is a decent version of the image, replacing the embedded JPEG. That’s why you may see complaints that Lightroom or another program is behaving oddly: the initial embedded JPEG may look better than the final version, so it looks as if the application is degrading the image quality as the file loads. Of course, in all cases, once the RAW file is available, you can make your own changes to optimize it to your taste.

There is a second use for these hidden JPEG files. If you shoot RAW without creating JPEG files and later decide you want a JPEG version, there are dozens of utility programs that will extract the embedded JPEG and save it as a separate file. (Google “JPEG extractor” to locate a freeware program that will perform this step for your Mac, PC, or other computer.)

But, as I noted, JPEG provides smaller files by compressing the information in a way that loses some image data. JPEG remains a viable alternative because it offers several different quality levels. At the highest quality Fine level, you might not be able to tell the difference between the original RAW file and the JPEG version.

In my case, I shoot virtually everything at RAW+JPEG Fine*. Most of the time, I’m not concerned about filling up my memory cards as I usually have my 128GB Sony G XQD memory cards, and several more Sony G and Lexar 64GB XQD cards with me. I also use a MacBook Air with an external 1TB hard drive. When shooting sports, I’ll shift to JPEG Fine (with no RAW file) to squeeze a little extra speed out of my camera’s continuous shooting mode, and to reduce the need to wade through eight-photo bursts taken in RAW format.

Image Size

Options: JPEG/TIFF: Large (default), Medium, Small; NEF (RAW): RAW L, RAW M, RAW S

My preference: Large

The next menu command in the Photo Shooting menu lets you select the resolution, or number of pixels captured as you shoot with your Nikon Z6. You can specify those sizes separately for both JPEG/TIFF files and 12-bit lossless compressed NEF (RAW) files. (Other RAW formats are available only in Large size.) Your choices and the resolutions are shown in Table 11.2.

Select image sizes using this menu entry or by pressing the i button and accessing the Image Size option (located by default in the second row underneath the Image Quality setting). Rotate either command dial or press OK to select size from a screen.

NEF (RAW) Recording

Options: NEF (RAW) Compression: Lossless compressed (default), Compressed, Uncompressed; NEF (RAW) Bit Depth: 12 bit, 14 bit (default)

My preference: Lossless compressed, 14 bit

When you’ve selected any NEF (RAW) setting for Image Quality, you can choose the type (amount) of compression applied to NEF (RAW) files as they are stored on your memory card, and whether the images are stored using 12-bit or 14-bit depth. The default values for type (Lossless compressed) and color depth (14 bit) work best for most situations, but there are times when you might want to use one of the other choices, as I’ll explain later in this section. (Figure 11.7, earlier, shows the options available in the long, scrolling list.)

Compression is a mathematical technique for reducing the size of a collection of information (such as an image; but other types of data or even programs can be compressed, too) in order to reduce the storage requirements and/or time required to transmit or transfer the information. Some compression algorithms arrange strings of bits that are most frequently used into a table, so that a binary number like, say, 1001011011100111 (16 digits long) doesn’t have to be stored as two 8-bit bytes every time it appears in the image file. Instead, a smaller number that points to that position in the table can be used. The more times the pointer is used rather than the full number, the more space is saved in the file. Such a compression scheme can be used to reproduce exactly the original string of numbers, and so is called lossless compression.

Other types of compression are more aggressive and actually discard some of the information deemed to be redundant from a visual standpoint, so that, theoretically, you won’t notice that details are missing, and the file can be made even more compact. The Nikon Z6’s RAW storage routines can use this kind of size reduction, which is called lossy compression, to reduce file size by up to about half with very little effect on image quality. JPEG compression can be even more enthusiastic, resulting in images that are 15X smaller (or more) and which display noticeable loss of image quality. You can choose NEF (RAW) compression and NEF (RAW) bit depth (see Figure 11.9, left).

Figure 11.9 Your Image Quality choices occupy two scrolling screens.

Under Type in the NEF (RAW) Recording menu, you can select from (see Figure 11.9, right):

- Lossless compressed. This is the default setting, and uses what you might think of as reversible algorithms that discard no image information, so that the image can be compressed from 20 to 40 percent for a significantly smaller file size. The squeezed file can always be restored to its original size precisely, with no effect on image quality.

- Compressed. Use this setting if you want to store more images on your memory card and are willing to accept a tiny potential loss in image quality in the highlights, after significant editing. (I’ve never been able to detect any effect at all.) The Z6 can achieve from 40 to 55 percent compression with this option. It uses a two-step process, first grouping some very similar tonal values in the mid-tone and lighter areas of the image together, and then storing each group as a single value, followed by a lossless compression scheme that is applied to the dark tones, further reducing the file size. The process does a good job of preserving tones in shadow areas of an image, with only small losses in the midtone and lighter areas. The differences may show up only if you perform certain types of extensive post-processing on an image, such as heavy image sharpening or some types of tonal corrections.

- Uncompressed. NEF images are stored without any compression applied. These files are larger and take longer to write to your memory card. In practice, there is little benefit from using this option.

The Bit Depth setting is another option that looks good on paper but, in the real world, is less useful than you might think. For most applications, the default value that produces 14-bit image files is probably your best choice, especially if you’re exposing images that will be combined using HDR (high dynamic range) software later. In that case, you can definitely gain some extra exposure “headroom” using 14-bit processing. The 12-bit setting saves some space and speeds up processing, but costs you a detectable amount of highlight detail.

As you may know, bit depth is a way of measuring the amount of color data that an image file can contain. What we call “24-bit color” actually consists of three channels of information—red, green, and blue—with one 8-bit bit assigned to each channel, so a 24-bit image contains three 8-bit channels (each with 256 different shades of red, green, or blue). A 24-bit color image can contain up to 16.8 million different colors (256 × 256 × 256; you do the math). Because each of the red, green, and blue channels always is stored using the same number of bits, it’s become the custom to refer only to the channel bit depth to describe the amount of color information that can be collected.

So, when we’re talking about 12-bit color, what we really mean are three 12-bit RGB channels, each capable of recording colors from 000000000000 to 111111111111 hues in a particular channel (in binary), or 4,096 colors per channel (decimal), and a total of 68,719,476,736 (68.7 billion) different hues. By comparison, 14-bit color offers 16,384 colors per channel and a total of 4,398,046,391,104 (4.4 trillion) colors.

The advantage of having such a humongous number of colors for an image that will, in the end, be boiled down to 16.8 million hues in Photoshop or another image editor is that, to simplify things a little, there is a better chance that the mere millions of colors you end up with have a better chance of being the right colors to accurately represent the image. For example, if there are subtle differences in the colors of a certain range of tones that represent only, say, 10 percent of a channel’s colors, there would be only 26 colors to choose from in an 8-bit channel, but 410 colors in a 12-bit channel, and a whopping 1,638 colors in a 14-bit channel. The larger number of colors improves the odds of ending up with accurate hues.

It’s not quite that simple, of course, because bit depth also improves the chances of having the right number of colors to choose from after the inevitable loss of some information due to noise and other factors. But in the real world, the difference between 26 colors and 410 colors is significant (which is why digital cameras always capture at least 12 bits per channel), and the difference between 12 bits and 14 bits (410 and 1,638 colors, respectively, in our example) is less significant. Because there is a penalty in terms of file size and the amount of time needed to process the image as it is recorded to your memory card, 14 bits per channel is not always your best option. Your two choices look like this:

- 12 bit. Images are recorded at 12 bits per channel in the RAW file, and end up with 12 bits of information per channel that is translated during conversion for your image editor either into 12 bits within a 16-bits-per-channel space or interpreted down to 8 bits per channel.

- 14 bit. This is the default bit depth for the Nikon Z6. At this setting, the Z6 grabs 16,384 colors per channel instead of 4,096, ending up as 14 bits in a 16-channel space or reduced to 256 colors by the RAW conversion software that translates the image for your image editor. You’ll find that such 14-bit files end up almost one-third larger than 12-bit files. 14-bit images are great for HDR photography.

ISO Sensitivity Settings

Options: ISO sensitivity: 100–51200, plus Lo 1 to Lo 0.3 and Hi 0.3 to Hi 2; Auto ISO Sensitivity Control: Maximum Sensitivity, Maximum Sensitivity with Flash, and Minimum Shutter Speed

My preference: Varies by subject type

You can make direct ISO settings without resorting to this menu entry. Just press the ISO button, located just south of the shutter release, and then rotate the front control dial to switch between Auto ISO and fixed ISO settings, and the rear dial to select specific ISO values.

This menu entry has two parts, which give you more flexibility through its ISO Sensitivity and Auto ISO Sensitivity Control adjustments. The former is simply a screen that allows you to specify the ISO setting, just as you would by spinning the main command dial while holding down the ISO button on the top-right panel of the Z6. The available settings range from Lo 1 (ISO 50 equivalent) through ISO 100–51200 to Hi 1–Hi 2 (ISO 204,800 equivalent). The available settings are determined by the size of the increment you’ve specified in Custom Setting b1: 1/3-, 1/2-, or 1-step values. Use the ISO Sensitivity menu when you find it more convenient to set ISO using the color LCD monitor.

The Auto ISO Sensitivity Control menu entry lets you specify how and when the Z6 will adjust the ISO value for you automatically under certain conditions. This capability can be potentially useful, although experienced photographers tend to shy away from any feature that allows the camera to change basic settings like ISO that have been carefully selected. But you needn’t fear Auto ISO. You can set some firm boundaries so the Z6 will use this adjustment in a fairly intelligent way.

When Auto ISO is activated, the camera can bump up the ISO sensitivity, if necessary, whenever an optimal exposure cannot be achieved at the current ISO setting. Of course, it can be disconcerting to think you’re shooting at ISO 400 and then see a grainier ISO 6400 shot during LCD review. While the Z6 provides a flashing ISO-Auto alert in the viewfinder and control panel, the warning is easy to miss. Here are the important considerations to keep in mind when using the options available for this feature:

- Off. Set Auto ISO Sensitivity Control to Off, and the ISO setting will not budge from whatever value you have specified. Use this setting when you don’t want any ISO surprises, or when ISO increases are not needed to counter slow shutter speeds. For example, if the Z6 is mounted on a tripod, you can safely use slower shutter speeds at a relatively low ISO setting, so there is no need for a speed bump. On the other hand, if you’re hand-holding the camera and the Z6, set for Program (P) or Aperture-priority (A) mode, wants to use a shutter speed slower than, say, 1/30th second, it’s probably a good idea to increase the ISO to avoid the effects of camera shake. If you’re using a longer lens, a shutter speed of 1/125th second or higher might be the point where an ISO bump would be a good idea. In that case, you can turn the automatic ISO sensitivity control on, or remember to boost the ISO setting yourself.

- Maximum sensitivity/Maximum sensitivity with flash. Use these parameters to indicate the highest ISO setting you’re comfortable having the Z6 set on its own. You can choose the max ISO setting the camera will use from ISO 200 up to ISO 51200, plus the two “expanded” settings all the way up to Hi 2. Use a low number if you’d rather not take any photos at a high ISO without manually setting that value yourself. Dial in a higher ISO number if getting the photo at any sensitivity setting is more important than worrying about noise. When using the Maximum Sensitivity with Flash setting, you can specify Same As Without Flash, so the camera will perform similarly both with and without an optional flash.

I’ve gotten surprisingly good results at ISO 25600; you should try it out yourself before ruling out this seemingly extreme ISO setting. Note that if you’ve selected an ISO setting that is higher than the Maximum Sensitivity you specify here, the Z6 will use the higher ISO value instead.

- Minimum shutter speed. This setting allows you to tell the Z6 how slow the shutter speed must be before the ISO boost kicks in, within the range of 30 seconds to 1/4,000th second. The default value is Auto. When Auto is highlighted, press the right multi selector button, and a screen appears allowing you to fine-tune Auto to respond Slower or Faster.

If you set a value manually, 1/30th second is a good choice, because for most shooters in most situations, any shutter speed longer than 1/30th is to be avoided, unless you’re using a tripod, monopod, or looking for a special effect. If you have steady hands, or the camera is partially braced against movement (say, you’re using that monopod), a slower shutter speed, down to 1 full second, can be specified. Similarly, if you’re working with a telephoto lens and find even a relatively brief shutter speed “dangerous,” you can set a minimum shutter speed threshold of 1/250th second. When the shutter speed is faster than the minimum you enter, Auto ISO will not take effect.

Your Z6 is one smart camera in Auto ISO mode. For example, if you accidentally set a minimum shutter speed that is faster or slower than you’ve specified in Custom Setting e1 (Flash Sync Speed) or Custom Setting e2 (Flash Shutter Speed), the camera will instead use a minimum shutter speed that is within the range set by e1 and e2. (You’ll find more on these Custom Settings in Chapter 12.)

You’ll recall that Program and Aperture-priority modes can adjust the camera’s shutter speed. When Auto ISO is active, the camera will adjust the ISO setting only if the minimum shutter speed specified here would produce underexposure. In all other cases, the Z6 will simply adjust the shutter speed to produce an appropriate exposure and not touch the ISO setting.

In addition, the camera is clever enough to try to use faster shutter speeds with telephoto lenses (which are more subject to camera-motion blur). This feature works only with autofocus lenses; older manual focus lenses not equipped with a CPU chip (described in Chapter 7) are not compatible with this extra function.

White Balance

Options: Auto: AUTO0 Keep White (default); AUTO1 Keep Overall Atmosphere; AUTO2 Keep Warm Lighting Colors; Presets: Natural Light Auto, Direct Sunlight, Cloudy, Shade, Incandescent, Fluorescent (seven types), Flash, Choose Color Temperature, Preset Manual

My preference: AUTO0 (Keep White)

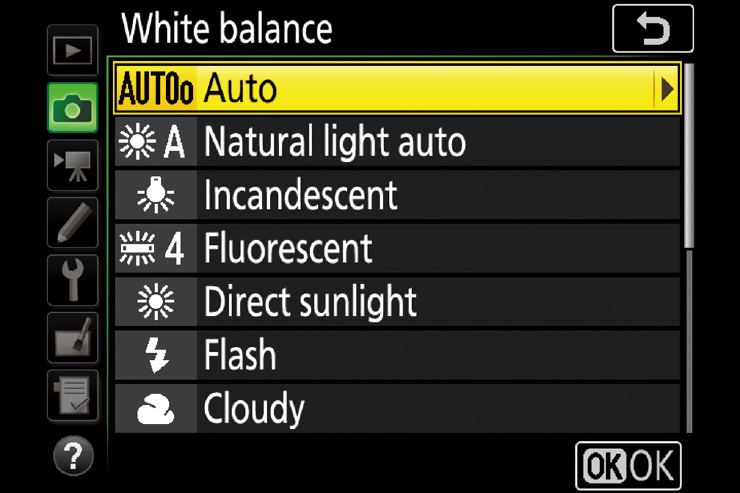

This setting is the first on the next page of the Photo Shooting menu. (See Figure 11.10.) It lets you tweak the white balance setting the Z6 applies to JPEG images, and which it embeds in the RAW image for interpretation by your image editor when the NEF file is imported. Your camera has a bewildering array of white balance settings, including three Auto modes, and, in practice, all of them are, at best, a little bit wrong. However, many are close enough that you may not notice the difference; all the presets can be adjusted by you using white balance fine-tuning (as described in Chapter 8); and, when importing RAW files, you have even greater flexibility.

Figure 11.10 The next page of the Photo Shooting menu.

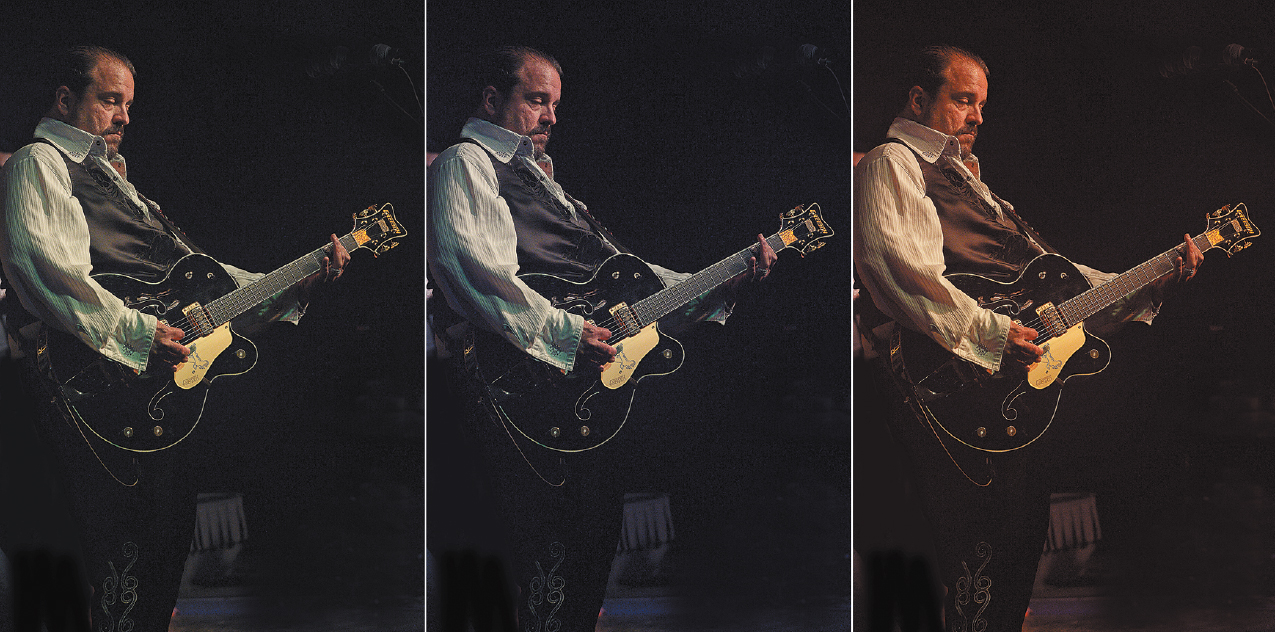

In addition to three varieties of full Auto white balance, this menu entry allows you to choose Natural Light Auto, Direct Sunlight, Cloudy, Shade, Incandescent, seven types of Fluorescent illumination, Flash, a specific color temperature of your choice, a preset value taken from an existing photograph, or a measurement you make. Some of the settings you make here can be duplicated using the Fn1 button on the front of the camera and main and sub-command dials, but the menus offer even more choices. Your white balance settings can have a significant impact on the color rendition of your images, as you can see in Figure 11.11.

Figure 11.11 Adjusting color temperature can provide different results of the same subject at settings of 3,400K (left), 5,000K (middle), and 2,800K (right).

The fastest way to change white balance settings is to use direct setting controls. Hold down the Fn1 button, then rotate the main command dial to choose one of the main settings. Your choices appear on the LCD monitor as you dial. When Auto, Fluorescent, K (Choose Color Temperature), or PRE (Preset Manual) are shown, you can also select a sub-option by holding down the Fn1 button and rotating the sub-command dial. You can also press the i button, select the White Balance icon (by default the first entry on the left of the second row), and rotate the main command dial and sub-command dial, as described above. I’ll explain your options next.

This menu entry offers additional options, including fine-tuning presets and ability to capture and store custom preset color temperatures. Select the White Balance entry on the Photo Shooting menu, and you’ll see an array of choices like those shown in Figure 11.12. (Three additional choices: Flash, K (Choose Color Temp.), and PRE Preset Manual are not visible until you scroll down to them.) If you choose Fluorescent, you’ll be taken to another screen that presents seven different types of lamps, from sodium-vapor through warm-white fluorescent down to high-temperature mercury-vapor. If you know the exact type of non-incandescent lighting being used, you can select it, or settle on a likely compromise.

The Choose Color Temp. selection allows you to select from an array of color temperatures in degrees Kelvin (more on this in Chapter 8) from 2,500K to 10,000K, and then further fine-tune the color bias using the fine-tuning feature described below. Select Preset Manual to record or recall custom white balance settings suitable for environments with unusual lighting or mixed lighting, as described later in this section.

For all other settings, highlight the white balance option you want, then press the multi selector right button to view the fine-tuning screen shown in Figure 11.13 (and which uses the Auto setting as an example). The screen shows a grid with two axes, an amber-blue axis extending left/right, and a green-magenta axis extending up and down the grid. By default, the grid’s cursor is positioned in the middle, and a readout to the right of the grid shows the cursor’s coordinates on the A-B axis (yes, I know the display has the end points reversed) and G-M axis at 0,0.

Figure 11.12 The White Balance menu has predefined values, plus the option of setting color temperature and presets you measure yourself.

Figure 11.13 Specific white balance settings can be fine-tuned by changing their bias in the amber-blue or magenta-green directions—or along both axes simultaneously.

You can use the multi selector’s up/down and right/left buttons to move the cursor to any coordinate in the grid, thereby biasing the white balance in the direction(s) you choose. The amber-blue axis makes the image warmer or colder (but not actually yellow or blue). Similarly, the green-magenta axis preserves all the colors in the original image, but gives them a tinge biased toward green or magenta. Each increment equals about five mired units, but you should know that mired values aren’t linear; five mireds at 2,500K produces a much stronger effect than five mireds at 6,000K. If you really want to fine-tune your color balance, you’re better off experimenting and evaluating the results of a particular change.

When you’ve fine-tuned white balance, either using the Photo Shooting menu options or the defined WB button (Fn1 is the default), left/right triangles appear in the white balance section of the control panel at lower right to remind you that this tweaking has taken place.

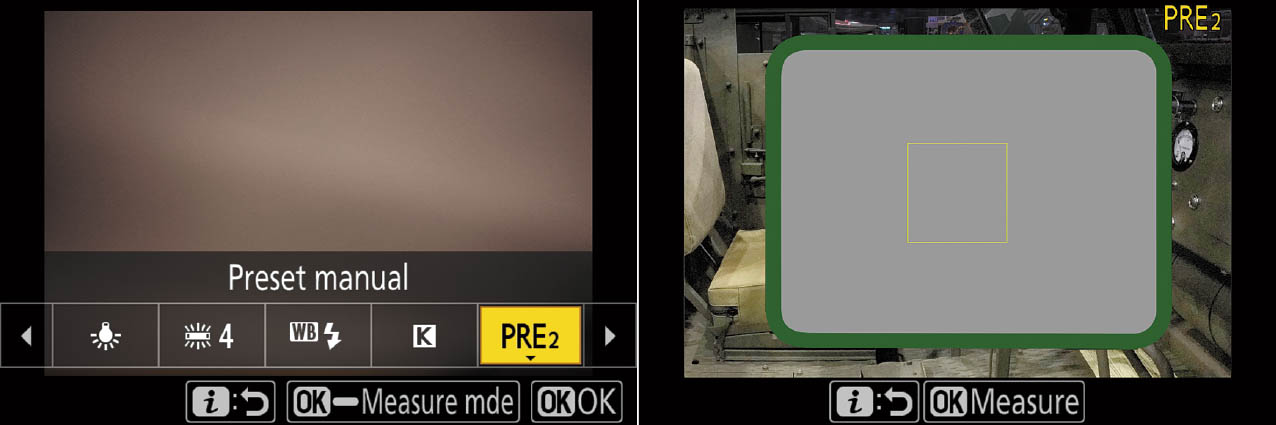

Using Preset Manual White Balance

If automatic white balance or one of the predefined settings available aren’t suitable, you can set a custom white balance using the Preset Manual menu option. You can apply the white balance from a scene, either by shooting a new picture on the spot and using the resulting white balance (Direct Measurement) or using an image you have already shot (Copy from Existing Photograph). To use an existing preset or perform direct measurement from your current scene using a reference object (preferably a neutral gray or white object), follow these steps:

- 1. Use gray or white reference. Place the neutral reference, such as a white piece of paper or a gray card, under the lighting you want to measure. You can also use one of those white balance caps that fit on the front of your lens like a lens cap.

- 2. Choose Preset Manual. Press the i button, choose White Balance, and rotate the main command dial until Preset Manual (PRE) is selected.

- 3. To use an existing preset value: Rotate the main command dial until the white balance you have previously stored is highlighted (“slots” d-1 to d-6). (See Figure 11.14.)

- 4. To define a new preset: Rotate the main command dial until the slot (d-1 to d-6) you want to use as your white balance register is highlighted. (See Figure 11.15, left.) Press and hold OK until the PRE icons in the shooting display and control panel start to flash. A white balance target frame will appear. (See Figure 11.15, right.)

Figure 11.14 When you capture a scene’s white balance, it will be stored in the selected slot.

Figure 11.15 To define a new preset, highlight the slot (d-1 to d-6), left. Then capture a neutral white or gray target (right).

- 5. Measure White Balance. Tap the touch screen at the point where your gray or white reference appears, or use the multi selector to move the target frame over that area. (Note that you can’t relocate the frame if a flash is attached.) Then press OK again or press the shutter release down all the way.

- 6. Success? If the Z6 was able to capture the white balance information, a message Data Acquired appears. If it was unable to measure white balance, you’ll be asked to try again. (Try using a different target if you fail on successive attempts.)

The preset value you’ve captured will remain in the slot until you replace that white balance with a new captured value. It can be summoned at any time (use the i button menu or Fn1) and when PRE is chosen with the main command dial, select your preset by rotating the sub-command dial until the desired white balance slot is displayed on the control panel. You can also choose an existing image or protect a captured white balance from being over-written:

- 1. Choose Preset Manual from the White Balance menu.

- 2. A screen of thumbnails appears, showing the six “slots” numbered d-1 to d-6. Use the multi selector buttons to highlight one of the thumbnail slots, and press the multi selector center button.

- 3. The next screen that appears (see Figure 11.16) has four options: Fine-tune, Edit Comment, Select Image, and Protect.

- Choose Fine-tune to fine-tune the amber/blue/magenta/green white balance of an image already stored in one of the four user slots.