1

Contexts for the organization of knowledge

Introduction

Information is only valuable to the extent that it is structured. Because of a lack of structure in the creation, distribution and reception of information, the information often does not arrive where it is needed and, therefore, is useless.

(Koniger and Janowitz, 1995, p. 6)

In my 30-year professional career I can’t remember a time when traditional US skills have been more vaunted by commmentators outside the profession. In an increasingly chaotic information world, the librarian as organiser, disseminator, selector, facilitator, and trainer is increasingly recognised.

(Foster, 1999, p. 149)

This chapter emphasizes the significance of the organization of knowledge. It explores some of the contexts in which we organize knowledge, and considers the contribution of the organization of knowledge to the wider issue of knowledge management. At the end of this chapter you will:

have considered the definition of knowledge and information

appreciate some of the characteristics of knowledge that are important to its organization and use

understand how the model of the 7 Rs of information management can be used to represent the processes associated with the creation and dissemination of knowledge and information

appreciate the distinction between information processing, information management and knowledge management.

Information is all around us. Our senses collect and our brains filter and organize information every minute of the day. At a very fundamental level information colours our perceptions of the world around us, and thereby influences attitudes, emotions and actions. Although the focus of this book is ‘recorded knowledge’ it is significant that the boundaries of ‘recorded knowledge’ are increasingly difficult to draw. For example, each product on the supermarket shelves carries ‘recorded’ information, concerning, say, its ingredients, its use, what it looks like and its value. At a more technologically sophisticated level, multimedia kiosks with information from Gardening Which? are made available in garden centres to support customers in the selection of garden products. Political parties and pressure groups seek to draw public attention to facts and figures that support their position or case. Planning documents are made available to facilitate local participation in decisions that affect the community. Television documentaries and historical dramas serve to enlighten us about the past and the present. Multimedia encyclopaedias include both text and information in other formats, such as sound and video. In all of these contexts, information shapes our perception of the society in which we live. Organizations collect data concerning the external market-place and internal processes and operations, which support the delivery of a quality product. Access to information is important in contributing to the quality of a manager’s decision-making. The way in which decisions are communicated is an indicator of the culture of an organization, and is likely to impact on employee involvement, empowerment and motivation, which are recognized to be some of the foundations for quality management. It is not difficult to subscribe to the view that:

Information is not merely a necessary adjunct to personal, social and organizational functioning, a body of facts and knowledge to be applied to the solution of problems or to support actions. Rather it is a central and defining characteristic of all life forms, manifested in genetic transfer, in stimulus response mechanisms, in the communication of signals and messages and, in the case of humans, in the intelligent acquisition of understanding and wisdom.

(Kaye, 1995, p. 37)

Martin describes information as the lifeblood of society:

Without an uninterrupted flow of the vital resource, society as we know it would quickly run into difficulties, with business and industry, education, leisure, travel, and communications, national and international affairs all vulnerable to disruption. In more advanced societies this vulnerability is heightened by an increasing dependence on the enabling powers of information and communications technologies.

(Martin, 1995, p. 18)

This chapter commences with a consideration of some definitions of the terms ‘information’ and ‘knowledge’. These definitions are used to identify the way in which our common understanding of these and related terms are intertwined. This is followed by a summary of the differing perspectives on the nature of information. There is a range of characteristics of information and knowledge that need to be considered in any approach to the organization of knowledge. The 7 Rs of information management is a model that identifies the stages in the creation and processing of information, and is useful in identifying the stages in which knowledge is structured. The chapter concludes with a short review of the essence of information processing, information management and knowledge management Chapter 2 follows this broad exploration of the contexts for the organization of knowledge by exploring the various ways in which recorded knowledge is formatted into documents.

Defining Information and Knowledge

A preliminary examination of some dictionary definitions of the concepts of ‘information’ and ‘knowledge’ serves as a starting-point. The Oxford English Dictionary (as quoted in Rowley, 1992, p. 4) provides a useful general definition:

Information is informing, telling, thing told, knowledge, items of knowledge, news.

This definition uses the related term Toiowledge’ to define ‘information’, so, in addition to making the observation that the two concepts are closely related, it might be useful to refer to the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of ‘knowledge’:

Knowledge is knowing, familiarity gained by experience; person’s range of information; a theoretical or practical understanding of; the sum of what is known.

(Rowley, 1992, p. 4)

The central significance of information has led many authors to seek to define the concept of ‘information’, and to better understand how information is, and might be, processed and managed. These contributions offer a variety of different perspectives, which can be summarized as five distinct definitions:

information as subjective knowledge

information as useful data

information as a resource

information as a commodity

information as a constitutive force in society.

It is helpful to explain each of these concepts.

Concepts of Information

Information as subjective knowledge

The concept of information as subjective knowledge is the concept that has attracted most attention, both from early thinkers in the library and information field and from the cognitive sciences.

The subjective knowledge held in the mind of the individual may be viewed as being translated into objective knowledge through public expression, via speech and writing. The information profession is primarily concerned with this objective knowledge. In particular, they are primarily interested in recorded knowledge as it appears in documents. More recent commentators in the field of knowledge management have distinguished between explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge might be viewed as equivalent to objective knowledge and a proportion of this explicit knowledge will be recorded in documents of various types. Tacit knowledge is the knowledge that is in the mind of the individual, and may be implicitly shared, probably through actions and shared ways of doing things within an organization.

Information as useful data

Another perspective on information can be gained by examining its relationship to data. This perspective derives primarily from the information systems literature, which is, agreed that ‘Information is data processed for a purpose’ (Curtis, 1989, p. 3) or ‘Information is data presented in a form that is meaningful to the recipient’ (Senn, 1990, p. 8). Senn continues:

It must tell the recipient something that was not previously known or could not be predicted. In other words it adds to knowledge but must be relevant for the situation in which it will be applied. The lack of knowledge - that is, the absence of information about a particular area of concern - is uncertainty.

(Ibid., p. 58)

Data is then, information that has undergone some processing and the results of that processing have been communicated for a particular purpose. If information is to be defined in terms of data - what then is data? Lester (1992) offers a simple perspective that is in line with other writers on information systems. He says:

In a business organization, many events take place in the course of a single working day. When the facts about such events are recorded, they become data, and we can thus say that data is the raw facts concerning occurrences or happenings in a business… raw data… is too voluminous. A system is needed which will transform raw data into meaningful information.

Lester, 1992. p. 191)

Information and knowledge as a resource

Many professional groups in organizations take an objective and instrumental view of information and knowledge that might be described as information and knowledge as a resource. This perspective holds that information is an objective resource, which is attainable and usable and which accordingly can be managed like other factors of production such as energy, raw materials and labour. Some proponents of knowledge management argue that knowledge is a key resource in determining competitive advantage and marketplace success in the knowledge-based society. They have sought to develop approaches to valuing knowledge as an asset, and to recording that asset on the balance sheet of a business. It is important to remember, however, that information is distinct from the more traditional factors of production such as labour and raw materials, in the following respects:

The value of information is not readily quantifiable - value depends on content and use, and, indeed, it may be argued that information as it rests in an electronic database has no inherent value.

Consumption of information - information is not lost when it is given to others. Information is not sacrificed when it is given or sold to others.

Dynamics of information - information is a dynamic force for change in the systems within which it operates and must be viewed within an organization as a formative organizational entity, rather than as an accumulated stockpile of facts. Information should influence decisions, affect what an organization does and how it does it and, ultimately, these actions and decisions will influence the information that is available for the next decision-making cycle.

Information as a commodity

Intellectual property laws, such as those associated with copyright are the precursors to a range of national and international laws and policies relating to trade in information and its associated goods and services. This has led to another view of information, that of information as a commodity. The concept of information as a commodity is wider than that of information as a resource, as it incorporates the exchange of information among people and related activities as well as its use. The notion of information as commodity is tied closely to the concept of value as it progresses through the various steps of creation, processing, storage and use.

Information as a constitutive force in society

Braman (1989) identifies the wider perspective of information as a constitutive force in society. Definitions of this type view information as not just being embedded within a social structure, but also as an agent in the creation of that structure. It may be argued that information policy decisions are inevitably coloured by the view of a society and are inextricably linked with culture and values.

Characteristics of Information or Knowledge

The exploration of the definition of knowledge and information in the previous section illustrates that there are multiple perspectives on the nature of knowledge and information. Knowledge, for example, cannot be organized and arranged like tins on the supermarket shelves (although books, which are one form in which knowledge is presented and through which information is disseminated, can be arranged on library shelves). Any discussions about the way in which knowledge or information can be managed, or structured, need to take into account a number of the characteristics of knowledge. These include objectivity, explicitness, currency, relevance, structure, and systems. We discuss each of these characteristics in turn.

Objectivity

The debate associated with the objectivity of knowledge is relevant to all types of knowledge and all disciplines. All knowledge is a product of the society and cultural environment in which it is created. However, the issue of objectivity has been most hotly debated in the social sciences. Social science researchers and knowledge users have been acutely aware of the difficulties associated with creating a shared reality, which could be regarded as valid and transferable objective knowledge. Science and technology, on the other hand, often investigates problems and environments where experiments can be repeated under similar conditions to give consistent results and what can be identified as objective knowledge. Related to the issue of objectivity are those of reliability and accuracy. Accuracy means that data or information is correct. Reliability implies that the information is a true indicator of the variable that it is intended to measure. Users often judge reliability of information on the basis of the reputation of the source from which it has been drawn.

Accessibility

Accessibility is concerned with the availability of knowledge to potential users. The distinction between implicit or tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge is relevant here. Tacit knowledge is subjective knowledge, which is owned by the individual or team. Most explicit knowledge is stored in the printed and electronic archives of societies (libraries) and organizations, and is, in general likely to be more accessible than tacit knowledge. However, the storage and communication media and the form and style of communication are also important. Knowledge may be stored and communicated via people, print or electronic media. A real challenge for most individuals and organizations is the integration of information that is presented in different formats. Also the form and style of communication needs to be amenable. The user’s subject knowledge, environmental context, language used and preferences all influence the success with which a message is received.

Relevance

Knowledge available to an individual must be appropriate to the task in hand. Knowledge available to an organization must be relevant, or pertinent, to its current direction, vision and activities. Knowledge is relevant when it meets the user’s requirements, and can contribute to the completion of the task in which the user is engaged, whether that task is decision-making, problem-solving or learning. Relevance can be assessed in relation to many of the other characteristics listed in this section, such as currency and accuracy, but may specifically be judged in terms of level of detail and completeness. Completeness is normally judged in relation to a specific task or decision; all of the material information that is necessary to complete a specific task must be available. In addition the level of detail, or granularity, of the information must match that required by the task and the user. We return to the concept of relevance and define a more specialized use of the term in Chapter 13.

Currency

Currency and life span of knowledge are important for two reasons - some information may supersede other information; the most current information is required, and outdated information needs to be discarded. Each type of information has its own life cycle. At one end of the time-scale there is a core of relatively stable knowledge for each discipline, such as the way in which the heart functions or the process for the refining of steel. Other information is outdated within hours. Examples include the weather report and international exchange rates. There is a real challenge in being able to recognize the positioning on a time-scale of specific knowledge and to be able to manage that knowledge in accordance with its life cycle. Users need to be presented with information that is still current, and collections of knowledge need to be weeded of redundant and outdated material.

Structure and organization

All knowledge has a structure. At the individual cognitive level, the brain holds associations between specific concepts. Structure is important to understanding. This cognitive structure is reflected in the way in which individuals’ structure information in their communications in the form of verbal utterances, text and graphical representations. Some disciplines have inherent structures; biology, for example, is organized in accordance with a structure that reflects the structure of living matter, and documents on biology can be organized in a way that is consistent with this structure. Newspapers, similarly group information into categories such as news, politics and sport. The two important features of this structure are:

the way in which items are grouped into categories

the relationships between these categories.

Systems

Structure is often imposed by systems, whether those systems are conceptual frameworks, communication systems or information systems. Knowledge will be communicated through information systems and stored in information systems. Such systems embrace people and hardware and software. The central theme of this book is the systems for the organization of knowledge. These systems need to be designed in order to achieve effective and efficient information retrieval. Such systems include printed indexes, card indexes, databases, OPACs, Web browsers and search engines.

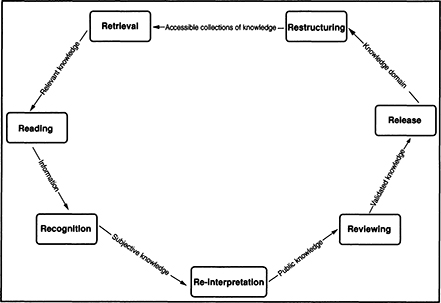

The 7 Rs of Information Management

Figure 1.1 is intended as a summary of the processes that contribute to information processing and the creation of knowledge. The significance of this model for this book is that knowledge or information is being organized, or structure is being imposed, during each of these processes. Information management as a discipline must be concerned with the management of all of these processes, although the professional group who describe themselves as information managers, or perhaps knowledge managers, are more involved with some of these processes than others. Some of these processes are performed by individuals, whilst others are performed by organizations, or, in some cases, information professionals on behalf of organizations. On the left-hand side of the model in Figure 1.1 are the processes that the individual performs in information management On the right-hand side are processes performed by organizations. The completion of all these processes may be supported by systems, but this will more evidently be the case in respect of those processes that are organizationally based. The relationships between the processes on the left-hand side of Figure 1.1 and those on the right-hand side are many to many. In other words, an individual may interact with the information management processes of many organizations and, on the other hand, any one organization will draw on the contribution of many individuals in the management of its knowledge base. It is the nature of this many-to-many relationship that poses some of the most significant challenges to information management. Perhaps, in passing it may be worthwhile to comment that Figure 1.1 does not explicitly identify the role of those responsible for the systems that facilitate each of the processes. Importantly, however, Figure 1.1 does emphasize that information and knowledge management involves a series of stages in a cycle.

Figure 1.1 The 7 Rs of information management

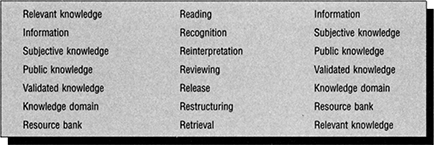

Figure 1.2 Inputs and outputs in the 7 Rs of information management

Perhaps the best way to explain the processes that comprise the information management cycle in more detail is to examine the inputs and outputs from each of these processes. Figure 1.2 summarizes the inputs and outputs from each of the processes.

Starting with the Reading process, the cycle in Figure 1.1 works like this:

A person Reads a collection of relevant knowledge recorded in both electronic and printed documents. They may also absorb other inputs from the external environment, or real-world data, using a range of data collection methodologies.

Once read, the relevant knowledge becomes information which is absorbed into the cognitive framework of the individual. This statement implies a definition of information as subjective knowledge. Other definitions of information exist and may be attractive to some audiences. The use adopted here allows a clear differentiation between knowledge and information, and relates both of these concepts to one of the 7 Rs. This process of Recognition is concerned with matching the concepts in the user’s cognitive framework with those in the document that is read. Recognizing is concerned with converting information into subjective knowledge.

Reinterpretation is concerned with the conversion of knowledge into a form that can be easily communicated, such as in a document. Although documents might be the primary concern of information managers, it is important to remember that public utterances can also be in verbal or graphical form. We describe this knowledge as public knowledge.

Review, or evaluation, is concerned with the conversion of public knowledge into validated knowledge. This process is conducted through the various channels that filter communications from individuals, at some stage in its process to the entry of validated knowledge. Typical activities concerned with validation include reviewing, refereeing, listing, and other processes for evaluating public knowledge.

Release or distribution is concerned with making public knowledge available within the community, organization or market-place that might find it to be of value. Once validated knowledge has been released, it enters the knowledge domain upon which individuals, organizations and communities can draw. Release for documents is typically in the form of publication, but other public announcements can also be made through, say, television, cinema, and other information media.

Organizations will interact with this knowledge domain, select items from it and collect or provide routes of access to a subject in the knowledge domain that they judge to be of specific interest in meeting their objectives. Processing that might be involved here might be data warehousing, indexing, and physical arrangement of printed documents. This may take place in libraries, document collections and document management systems. All such processes can be said to broadly fit into the category of restructuring of knowledge to meet a specific purpose. This collection of knowledge will be supplemented within organizations by information that emerges from the collection of transaction-based data, such as sales data, within the organization.

This accessible collection of knowledge will then be used by individuals as a resource from which they can Retrieve relevant knowledge. Users will approach this collection with individual objectives, and seek to differentiate between relevant knowledge and rubbish as defined by their specific objectives.

Relevant knowledge, once retrieved, must be Read before the knowledge recorded in documents of various types can be converted into information and the cycle can recommence.

The cycle in Figure 1.1 shows the stages in the order in which they are often encountered. However, the processes may occur in alternative orders. For example, Review may occur, before or after Release. If the stages are switched, then the inputs and outputs to the processes need to be adjusted accordingly. In addition, there are, of course, many subprocesses within each of the processes identified in this model. Restructuring is particularly concerned with the collection of knowledge in libraries, document collections and databases, and the structuring of these collections of knowledge. This is the primary focus of this book. Such collections are, however, of no value unless individuals use them to retrieve knowledge, and it is therefore also important to consider the Retrieval stage, which is concerned with information retrieval.

Information Processing, Information Management and Knowledge Management

There is a sense in which all members of knowledge-based society and the organizations within that society engage in information management and the organization of knowledge. Here we seek to differentiate between:

information processing which is conducted by all members of a knowledge-based society

information management which is concerned with managing information on behalf of others, within an organization or a community, and is primarily the domain of the professional information manager

knowledge management which is concerned with creating organizations and societies in which subjective, tacit knowledge can be converted into objective knowledge and shared in the pursuit of communal or organizational objectives, and is the domain of politicians, chief executives and senior managers.

The structuring and organizing of information and knowledge is performed in all three of information processing, information management and knowledge management The agents involved in the structuring and organization differ, and it is useful to recognize the basic differences between the roles of these different parties.

Information Processing

Information processing is doing something to information to make it into something else. Curtis (1989), for example identifies the following as types of information processing:

classification of data

rearranging/sorting data

summarizing/aggregating data

performing calculations on data

selection of data.

Information processing might then be viewed as an activity common to all information users. As a society or organization becomes increasingly knowledge based, the extent of individual involvement in these processes and the expertise required of individuals in their execution increases.

Information Management

Information management is concerned with the promotion of organizational (and possibly societal) effectiveness through the enhancement of the capabilities of the organization in coping with the demands of its internal and external environments in dynamic as well as stable conditions. Fairer-Wessels is more specific about the processes that this involves:

Information management is viewed as the planning, organising, directing and controlling of information within an open system (i.e. organisation). Information management is viewed as using technology (e.g. computers, information systems, IT [information technology]) and techniques (e.g. information auditing/mapping) effectively and efficiently to manage information resources and assets from internal and external sources for meaningful dialogue and understanding to enhance pro-active decision making and problem solving to achieve aims and objectives on a personal, operational, organisational and strategic level of the organisation for competitive advantage and to improve the performance of the system and to raise the quality of life of the individual (by teaching him/her information skills, of which information management is one, to become a global citizen).

(Fairer-Wessels, 1997, p. 99)

Information managers are professionals who act as agents on behalf of information processors to create and continuously improve systems, so that information processors are better able to meet their objectives. Information managers need to be able to understand and interpret these objectives in the context of the resources available to them. The structuring of knowledge is a key role for information managers, and there will be a continuing need for professionals who can perform this structuring on behalf of others, either through systems and knowledge design, or through support to searchers.

Knowledge Management

Knowledge management is concerned with the exploitation and development of the knowledge assets of an organization with a view to furthering the organization’s objectives. The knowledge to be managed includes both explicit, documentary knowledge and tacit or subjective knowledge, which resides in the minds of employees. Knowledge management embraces all of the processes associated with the identification, sharing and creation of information. Successful knowledge management requires systems for the management of knowledge repositories, and to cultivate and facilitate the sharing of knowledge and organizational learning. Knowledge management projects focus on one or more of the following four objectives:

To create knowledge repositories, which store both knowledge and information, often in documentary form. A common feature is ‘added value’ through categorization and pruning.

To improve knowledge access, or to provide access to knowledge or to facilitate its transfer among individuals; here the emphasis is on connectivity, access and transfer, and technologies such as videoconferencing systems, document scanning and sharing tools and telecommunications networks are central to this objective.

To enhance the knowledge environment so that the environment is conducive to more effective knowledge creation, transfer and use. This involves tackling organizational norms and values as they relate to knowledge.

To manage knowledge as an asset, and to recognize the value of knowledge to an organization. Assets, such as technologies that are sold under licence or have potential value, customer databases and detailed parts catalogues are typical of companies’ intangible assets to which a value can be assigned.

Summary

Information and knowledge are the lifeblood of organizations and society, but to be useful they need to be structured and organized. This chapter commences with a consideration of some definitions of the terms ‘information’ and ‘knowledge’. These are used to identify the way in which our common understanding of these and related terms are intertwined. This is followed by a summary of the differing perspectives on the nature of information. The following characteristics of information and knowledge need to be considered in any approaches to the organization of knowledge: objectivity, accessibility, relevance, currency, structure and organization, and systems. The 7 Rs of information management is a model which identifies the stages in the creation and processing of information, and is useful in identifying the stages in which knowledge is structured. Information and knowledge may be structured and organized through information processing, information management and knowledge management.

References and Further Reading

Bladder, F. (1995) Knowledge, knowledge work and organisations: an overview and interpretation. Organisation Studies, 16 (6), 1021–1046.

Braman, S. (1989) Denning information: an approach for policymakers. Telecommunications Policy, 13 (3), 233–242.

Brookes, B. C. (1974) Robert Fairthorne and the scope of information science. Journal of Documentation, 30 (2), June, 139–152.

Buckland, M. (1991) Information as a thing. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42 (5), 351–360.

Butcher, D. R. and Rowley, J. E. (1998) The 7 R’s of information management. Managing Information, 5 (2), March, 34–36.

Choo, C. W. (1996) The knowing organisation: how organisations use information to construct meaning, create knowledge and make decisions. International Journal of Information Management, 16 (5), 329–340.

Cronin, B. and Davenport, E. (1991) Elements of Information Management Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Curtis, G. (1989) Business Information Systems: Analysis, Design and Practice. Wokingham: Addison-Wesley.

Davenport, T. H., DeLong, D. W. and Beers, M. C. (1998) Successful knowledge management projects. Sloan Management Review, 39 (2), Winter, 43–57.

Davenport, T. H. and Prusak, L. (1998) Working Knowledge: Managing What your Organisation Knows. Boston: Harvard Business School Press

Demarest, M. (1997) Understanding knowledge management. Journal of Long Range Planning, 30 (3), 374–384.

Eaton, J. J. and Bawden, D. (1991) What kind of resource is information? International Journal of Information Management, 11, 156–165.

Fairer-Wessels, F. A. (1997) Information management education: towards a holistic perspective. South African Journal of Library and Information Science, 65 (2), 93–102.

Fairthorne, R. A. (1965) Use and mention in the information sciences. In Proceedings of the Symposium for Information Sciences, September. Washington: Spartan Press.

Foster, A. (1999) Knowledge management - not a dangerous thing. Library Association Record, 101 (3), 149.

Kaye, D. (1995) The nature of information. Library Review, 44 (8), 37–48.

Koniger, P. and Janowitz, K. (1995) Drowning in information, but thirsty for knowledge. International Journal for Information Management, 15 (1), 5–16.

Lester, G. (1992) Business Information Systems. London: Pitman.

Martin, W. J. (1995) The Global Information Society. Aldershot: Aslib/Gower.

Mullin, R. (1996) Knowledge management: a cultural revolution. Journal of Business Strategy, 17 (5), September-October, 56–60.

Nonaka, I. (1991) The knowledge creating company. Harvard Business Review, 69, November-December, 96–104.

Nonaka, I. (1995) The Knowledge Creating Company. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nonaka, I. (1996) The knowledge creating company. In K. Starkey (ed.) How Organisations Learn, pp. 18–31. London: International Thomson.

Ruggles, R. (1997) Knowledge Management Tools. Boston: Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann

Senn, J. A. (1990) Information Systems in Management, 4th edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Skyrme, D. J. and Amidon, D. M. (1998) New measures of success. Journal of Business Strategy, 19 (1), 20–24.

Wilson, D. A. (1996) Managing Knowledge. Oxford and Boston: Institute of Management and Butter-worth Heinemann.