13

Management of systems for the organization of knowledge

Introduction

The infrastructure for systems for the organization of knowledge has three components: databases, hardware and software. All of these three components need to be designed and maintained. Business organizations will take responsibility for performing these activities in relation to the transaction and management information systems that underpin the effective operation of the organization. Commercial software developers and information providers are concerned to develop the quality of their product and to maintain their competitive position. Public sector organizations and businesses play roles in designing and maintaining systems that support the organization of public and published knowledge. They make a national and international contribution to the development of systems that ensure the preservation of, and access to, the knowledge and information that forms our cultural heritage and economic wealth. This chapter considers the following aspects of the design and maintenance of systems:

evaluation of systems for the organization of knowledge and information retrieval

maintaining databases and authority control

managing systems

evolving and migrating systems

organizations in the organization of knowledge.

Some of these issues will be considered in greater detail in texts on information systems. They are briefly listed here lest in enthusiasm for the richness of knowledge we forget the platforms that facilitate organization and access to knowledge. The most important message embedded in this chapter is that systems for the organization of knowledge are dynamic. Users, information professionals and others involved with the design and maintenance of such systems need to manage that change.

Evaluation of Systems for the Organization of Knowledge and Information Retrieval

An important aspect of the management of systems for the organization of knowledge is the evaluation of those systems. Both researchers and systems producers participate in the evaluation of systems. This section explores some of the key measures that can be used in the evaluation of the success of information retrieval, and then briefly identifies the approaches available to performing evaluation.

Recall and precision have been traditional measures in the evaluation of information retrieval systems. While they are still important, as discussed below, they are not the only measures that can be used. Accordingly, the approaches for the evaluation of information retrieval systems are often concerned to gather a more general perspective on the user’s reaction to the system, rather than simply considering recall and precision. In addition, it is important to remember that there are two perspectives on the evaluation of information retrieval systems, characterized by the two distinct questions:

How can we design the best system?

or

Given a specific system, how can that system be searched most effectively?

Evaluation Measures: Recall and Precision

Recall and precision, the classic measures of the effectiveness of a retrieval system, have been mentioned in a number of places in the course of this book. It is now time to discuss them more fully. Recall relates to the system’s ability to retrieve wanted items in a subject (as opposed to a known-item) search. Precision relates to the system’s ability to filter out unwanted items. The two are capable of being measured under controlled conditions, and it is usual therefore to express them as ratios. A search for documents in a database has four possible outcomes:

Some relevant items are successfully retrieved. These we call Hits.

Some items that are not relevant are retrieved. This is known as Noise.

The search fails to retrieve some relevant items. These are Misses.

Some irrelevant items are not retrieved. These have been successfully Dodged.

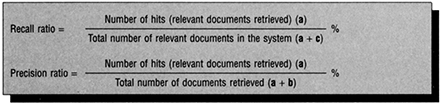

The recall ratio is the number of hits (relevant documents that have been retrieved) as a percentage of the total number of relevant documents in the system or database. The precision ratio is the number of hits (relevant and retrieved documents) as a percentage of the total number of documents retrieved, whether relevant or not (Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1 Recall and precision ratios

Indexing systems and search software should be designed to maximize both recall and precision: that is, to minimize Noise (2) and Misses (3). However, in a given search, recall and precision are usually held to be inversely related: to improve the one, the other tends to be reduced. Suppose a person is searching for items about asbestos roofing. The topic is represented in the collection, but only in a limited quantity. It is, however, possible to broaden the search and find additional information on asbestos roofing by retrieving general documents on roofing and extracting pertinent sections. This will trace more information on asbestos roofing, but only by considering all the documents listed under the much broader category of roofing. The search will have retrieved a number of non-relevant documents (noise). By broadening the search we have improved the recall but at the cost of lower precision.

It is thus unlikely to be possible to achieve a system that gives 100 per cent recall at the same time as 100 per cent precision. Thus anyone designing a retrieval system must choose an appropriate blend of recall and precision for each individual application. Quite frequently a user will be satisfied with a few items on a topic as long as they are relevant and meet other criteria such as language, date and level. Here, high precision and low recall are satisfactory. On other occasions, as, for example, when planning a research project, a user may want every document or piece of information on a topic traced, and then high recall must be sought to the detriment of precision.

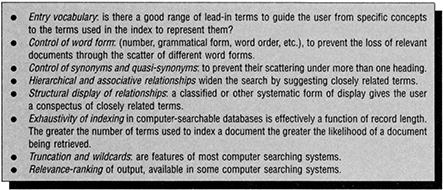

Figure 13.2 Index language devices influencing recall

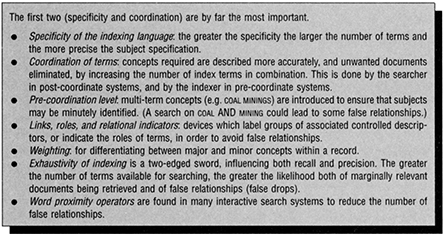

Figure 13.3 Index language devices influencing precision

An indexing language has a number of devices that improve recall (Figure 13.2), balanced by devices for improving precision (Figure 13.3).

Controversy has always surrounded recall and precision. Some of the problems may already have suggested themselves in the course of reading this account. The more important ones are summarized as follows:

What is a relevant document? Relevance is not a black and white concept. Retrieved documents may be highly suitable to a particular information need, or marginally so. It has already been suggested that users look at other criteria besides pure subject relevance when deciding whether a retrieved document is suitable to their needs. Other measures, including novelty and accuracy, have been proposed to refine the concept of relevance.

Recall and precision originally assumed delegated, as opposed to end-user conducted, searching. In the latter the searcher is able to reject irrelevant material heuristically during the course of the search. Hence precision is, indirectly, a measure of user time and effort.

The concept of retrieval assumed that a document is either retrieved or it is not. The results of many search systems are now relevance ranked. In end-user conducted searches recall is also an indirect measure of user time and effort.

Under working conditions it is impossible without scanning the entire database to know the total number of relevant documents in the system. Relative recall tries to get round this problem by comparing the numbers of documents retrieved by different indexing systems applied to the same database.

The concept of the database is no longer clear-cut. Many external online systems permit searching on a range of databases simultaneously. The World Wide Web is a ‘bottomless pit’, the extent of which can only be estimated. If the size of the database is not known for certain, then it is impossible to know how many relevant documents it contains.

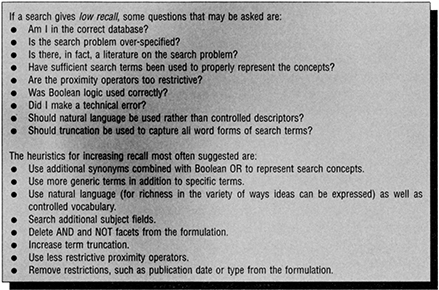

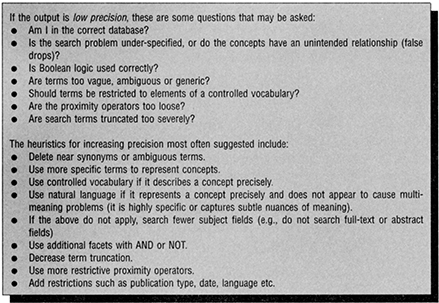

For all the difficulties surrounding recall and precision, they remain invaluable as rule-of-thumb evaluation measures, especially when reviewing search results. Figures 13.4 and 13.5 list some of the practicalities for improving searches that deliver low recall and low precision respectively.

Other Measures

Recall and precision are measures of index effectiveness, indicating the extent to which relevant documents are retrieved. A good information retrieval system must also be efficient and cost-effective. Other measures that are used to evaluate the efficiency of the system might include the following:

The time that it takes to perform a search. This is an important parameter for the individual user but, unfortunately, general measures are likely to prove elusive. The time that it takes to perform a search in a system is a function of a number of factors, including the user’s previous experience with the system, aspects of system design and the nature of the search. In an experimental situation some of these variables could be controlled, and average search times could be computed for different systems. The time taken to perform a search is not only a function of the indexing language and the system, but may also be affected by system response times, available search facilities and interface features.

Figure 13.4 Low recall in search results

Figure 13.5 Low precision in search results

Cost is a further measure of system effectiveness. Clearly, it is desirable to minimize search costs that include any expense associated with the acquisition of the source or access to it, as well as the searcher’s time. The economics of accessing data through different media, such as networked CD-ROM and Web access, vary considerably. For external databases, these costs depend upon the pricing strategy for access to the database through different routes. For internal databases, it may be difficult to separate search cost from data input and system maintenance costs. Another factor in cost is that natural-language indexing tends to shift the intellectual effort necessary for effective retrieval to the end-user. This collection of factors makes it difficult to calculate the cost of a search, but, nevertheless, cost remains an important factor.

Usability is another key factor in system evaluation. This concept was introduced in Chapter 5. Usability needs to take into account both interface design and the nature of the indexing language. Usability may affect the cost of searching, and the speed with which retrieval can be achieved. It will also impact upon training requirements.

Evaluation: Processes

There are a number of different approaches to the evaluation of information retrieval systems. Early tests sought to explore in some depth the effectiveness of different indexing languages, often in a card-based retrieval environment. This work on indexing languages has continued, but most of the more recent work has focused on the search behaviour of searchers in specific environments, such as using search engines on the Web, CD-ROM and OPACs. These studies recognize that, while the indexing language is a factor which contributes to search success, a number of other factors are also important, including:

the searching style of the searcher

subject area, and the precision associated with terminology in a subject area

the number of databases used in a search.

System evaluation needs to embrace all aspects of the system, including specifically the interface, the indexing language, the nature of the databases being searched and other aspects of the context in which the system is being used. Typically, it is also important to take into account the characteristics of intended user groups. There are two arenas for evaluation:

Evaluation by the producer of the information product during the design process and subsequent to the design process, in order to gain user feedback that will influence the design of upgrades and subsequent versions of the system. Evaluation is the gathering of data about the usability of a product for a specific activity within a specific environment. In general, the objective of evaluation is to find out what the users want, and what problems they experience, with a view to improving product design.

Evaluation conducted by researchers who are interested in establishing general principles about systems, possibly in relation to user needs and behaviours, or the effectiveness of specific system features. Recently this research has focused on the following issues: search engines; retrieval evaluation; the reliability of information on the Web; user interfaces; user search behaviour; information organization on the Web; vocabulary control; intelligent search agents; and, analyses of the relative performance of the Web, online and CD-ROM.

Possible approaches to system evaluation include:

Observing and monitoring users’ interaction, in either a laboratory setting, or the environment in which a search would normally be performed. The most popular approaches are those which involve some kind of indirect observation. Examples of such approaches are those in which a video recording of the user is made, or where the keystrokes that the user performs are logged through data logging or transaction logging.

Eliciting users’ opinions, which can offer a greater insight into why users perform particular actions, or pursue specific search strategies and can identify the problems that users might have with a system. Approaches which may be helpful in this context include individual interviews, focus groups (group interviews), questionnaires and surveys.

Experiments or benchmark tests in which the experimenter seeks to control some of the variables, while examining the effect of varying others. Typically such tests are conducted in a laboratory environment and work focuses on usability objectives and measures. Typical usability objectives might be suitability for the task, learnability and error tolerance.

Prototyping, in which the user and the designer work together to evolve the system. This may be performed in a laboratory setting, or in a real-life setting. The designer creates a prototype; the user tests the prototypes, and identifies any weaknesses in the prototype; the designer produces a further prototype, and so on until the designer is satisfied that the prototype meets the user requirements.

Predictive evaluation, is concerned with predicting the usability of a product without direct feedback on users’ opinions. Prediction is typically based on expert reviews and usage simulations. These simulations may be more or less structured. One way of structuring such simulations is to use walkthroughs. Walkthroughs require experts to simulate the actions that a user might take in using the system. Experts are asked to report on their experience with the system.

Maintaining Databases and Authority Control

Chapter 5 discusses the various different types of databases, and notes that a range of print or electronic products may be produced from one database, and packaged to meet the particular needs of a specific groups of users. All databases or other knowledge repositories need to be kept up to date, in other words, new information needs to be added. There are three different kinds of amendments that can be made to a database:

addition of new records

amendment of existing records

deletion of existing records.

Bibliographic databases are updated primarily by adding new records to the established collection of records. Catalogue databases may be updated by adding new records to correspond to additions to stock but, also, amendments may be made to existing records to accommodate, for example, the relocation of a document or the removal of documents from the collection. Other databases, such as directory databases, are primarily updated with corrections to existing records, such as changes of address, or amendments to an entry to reflect the latest social or technological developments.

Authority Control

A key issue in updating bibliographic records is authority control. Authority control is concerned with the maintenance and application of standard access points or index terms. Authority control consists of the creation of authority records for established headings, the linking of authority and bibliographic records, and the maintenance and evaluation of an authority system. Authority control can be exercised locally or within a regional or international network. Three kinds of authority control can be maintained: for names, for subjects, and for classification.

Name authority control has three purposes:

to ensure that works by an author are entered under a uniform heading

to ensure that each heading is unique - i.e., to prevent works by more than one author from being entered under the same heading (i.e., to manage the collocative function of the catalogue)

to save having to establish the heading every time a work is catalogued.

When a personal or corporate name is used for the first time, a name authority record is made. This contains:

the heading, usually based on AACR

the sources used in establishing the heading

tracings for references to the heading.

If a heading changes, the name authority record is updated and all existing catalogue entries under that heading are altered. Cataloguers of the old school used to await in eager anticipation the publication of the Queen’s new year and birthday honours lists in order to discharge this function. Today, the first use of a name is more likely to be within the offices of a national bibliographic agency. Bibliographic agencies may contact authors whose names are not represented on their authority files, to verify their full and preferred form of name, any other names they may have used and their date of birth. The library of Congress and the British library are cooperating in setting up a joint name authority file, which is made available to other bibliographic utilities and to individual subscribers, to be used as the basis for their own authority files.

Where authority control is automated, it is feasible to link the name authority file to the bibliographic file. The catalogue maintenance modules of many automated library systems check headings as they are entered, warn if a heading is not on file and display close matches. They may also allow authority control on other fields of the record, e.g., names of publishers.

Subject authority control exists to ensure that subject headings, and their references, are applied uniformly and consistently. A subject authority record is made whenever a new subject heading is established. It contains:

the heading

a scope note, if required

sources used in establishing the heading

details of references to and from the heading.

This comes very close to the contents of a thesaurus record and, indeed, many a published thesaurus began life in this way. A thesaurus that has been developed for in-house use may act as its own authority file.

Many LCSH headings are synthesized by the use of subdivisions that do not specifically appear in the list, or may be personal, corporate or geographic names which are excluded from the list. These headings are published by the library of Congress and are available in a variety of formats, including CD-ROM as CDMARC Subjects.

Shelfmark control is carried out by means of a shelflist a set of records, one for each physical bibliographic unit, arranged in the order in which they are shelved. This is used primarily as an inventory list, for stock control. It may hold acquisition details or other management information relating to the specific item. In libraries where a unique shelfmark is assigned to each item, it is used in assigning individual book numbers. In libraries with dictionary catalogues, it may be accessible to readers as a classified list. The shelflist is typically held on cards. Many libraries with automated catalogues no longer maintain a shelflist.

The USMARC format for classification data has been developed by the library of Congress, who maintain an authority record for DDC and LCC classmarks as applied. Like LCSH headings, many classmarks are formed by synthesis or, in the case of LCC, by alphabetical subarrangement.

Database Maintenance

Thesauri, classification schemes and lists of subject headings need to be kept up to date. New subjects emerge and need to be represented within the scheme. The key issues in the maintenance of such lists are:

the identification of new subjects, as they arise in the literature to be indexed

a process for agreeing on the notation or terms that are to be used to represent those new subjects

the identification of relationships between new subjects and existing subjects

processes for recording both new subjects and their relationships with other terms

processes for notifying all indexers using the scheme of the modification

processes for ensuring that searchers have access to an up-to-date version of the controlled indexing language.

When a controlled indexing language is used only to index one database or document, it is relatively straightforward, especially with the aid of special software for thesaurus maintenance, to maintain a current version of a thesaurus, to which all indexers may have access. On the other hand, for the large classification schemes, such as the Dewey Decimal Classification, or subject headings lists such as the library of Congress Subject Headings list, agreement on new terms may require elaborate and extensive consultation. Indexers all around the world may need to be notified of changes, and changes could have a potential impact on many libraries, search intermediaries and end-users.

In the context of subject terms and classification codes two issues cause complexities:

As well as the addition of a term, it is necessary to ensure that all relationships between that term and earlier and related terms have been adequately indicated. Significant new areas of knowledge may require new sections in classification schemes, or a collection of new related terms in a subject headings list or thesaurus.

Many subject terms and classification codes are drawn from published lists or schemes, and revision requires agreement on the introduction of such terms. This agreement may inject a delay in the updating of the lists or schemes. The issue of revision for classification schemes has been explored more fully in Chapter 8.

Reclassification may involve a once and for all migration to a different classification scheme, or the routine updating of the existing scheme. Changes affecting the physical distribution of stock in a library may involve significant effort and disruption to the library’s normal operation. The components of this exercise are:

Retrieve documents.

Retrieve records.

Amend classmark on document and record.

Re-file documents.

Re-file records.

Measures which may be taken to reduce the disruption include:

Rolling reclassification: separate classes are reclassified consecutively.

Reclassification by osmosis: new accessions only are classified by the new system. Existing stock is gradually weeded out, leaving only a small nucleus of old stock to be reclassified.

Managing Systems for Knowledge Organization

The hardware and software platforms that support access to knowledge need to be managed and users need to be supported in their access to such systems. Typically, this involves attention to day-to-day maintenance issues and system integrity, security and user support.

System Maintenance

System maintenance is concerned with keeping the hardware and software working. This involves:

monitoring the quality and integrity of databases, from a more technical perspective than outlined above. In other words, it is important that all of the most recent version of the database is available to those users who are authorized for access

dealing with any hardware or software malfunctions, such as faulty workstations or software bugs

making sure adequate backups of databases are taken

troubleshooting any situations where the system does not work as it might and, in general, having and being able to implement contingency plans in a crisis

implementing upgrades of software and hardware, to existing systems. This might include the installation of new workstations or further developments to an existing network. Upgrades to software may offer new features and facilities; users need to be informed of any changes that affect their interaction with the system

liaison with hardware and software suppliers, in relation to both new and future developments.

Security

The other side of access to information is security. Proper attention to security ensures that:

All users have access to the databases and functions for which they are authorized.

No users have access to databases and function for which they are not authorized.

Loss of security occurs from both accidental and deliberate threats. Accidental threats arise from poor system features such as overloaded networks or software bugs. Deliberate threats arise from human intent, and include theft, computer fraud, vandalism and other attempts to break the system. Typically such threats may lead to:

the interruption of data preparation and data input

the destruction or corruption of stored data

the destruction or corruption of software

the disclosure of personal proprietary information

injury to personnel

removal of equipment or information.

Security is a particular challenge in systems where the users are not members of the staff of a specific organization. Libraries, online search services and publishers will want to implement security that is linked to the licensing arrangements that have been contracted with organizations or individual users. Security issues in this context cover everything from the security of items in the library’s collections, to privacy concerning user information. As a quick checklist, some of the issues are:

authentication of the user, so that users can only access their own accounts

security of hardware, to avoid theft or vandalism

prevention of hacking into networks, leading to access to other databases that should not be publicly accessible

data privacy, concerning user information

item identifiers, and ensuring that these are unique

buildings’ design, to increase hardware and user security.

Increasingly systems will facilitate user access to commercial databases, library resources in a number of libraries and document collections. The systems must tackle issues concerning liability, control of copyright, licensing and collecting of appropriate payments. Asset trading agreements will increasingly be forged across the information chain. Such systems may also need to accommodate the assessment and evaluation of resources by those seeking to acquire them. Systems will need to be able to manage who is allowed access to what, when, for how long or to what maximum charge, payment strategy and associated rights. They will need to manage copyright issues as an integral function, and will need to be linked to the systems of publishers, editors, indexers, picture libraries and authors.

Security will increasingly be linked to charging. Providing access to the wealth of Internet resources is expensive; Smartcards that record customers’ transactions are likely to be used increasingly to support charging, and may also be used as the security device for access to a range of organizational and external information resources. They could also be used with self-help kiosks.

User Support

User support is concerned with ensuring that all potential users of a system can make effective use of that system. Chapter 6 has reviewed the different categories of users. Another significant group of users is information professionals, who may use a system on behalf of other users. Support will be offered through a combination of:

Documentation, in both online and printed form. Lists of key operations, commands and menu options are particularly helpful in print format. Many systems now have extensive help systems available on screen, but these may not be attractive when remote communication implies costly additional time online. In addition, with some help systems, help is needed in navigating the help system!

Training through courses, seminars and one-to-one hands-on sessions. Users of library systems fall into two categories: staff and library users. User training for staff can proceed as with many other systems, although, due to the exigencies of the issue desk, much training may need to be conducted on a one-to-one basis. Training for library users is much more difficult to achieve in many libraries. The position is better in academic and organizational libraries than in public libraries, but there is always some fluidity of clientele and, generally, a lack of interest in systematic training. The immediate focus for library users is often on the OPAC and associated CD-ROM products.

Interface design - with sophisticated GUIs, implicit support can often be integrated into the interface design. Appropriate labels in menus, and good icon design, coupled with different interfaces for quick search and advanced search can do much to make the search process intuitive.

Help desks, and other in-person support, available either remotely or at the location where the user is likely to perform the search. These are particularly valuable for problem-solving, troubleshooting and supporting the new user.

Evolving and Migrating Systems

Over the past 20 years technological developments have led to many changes in the systems platforms. Changing the platform on which a database is mounted, or which provides user access to information or knowledge, is a significant project which will affect both operations as conducted by information professional staff and the services available to, and accessed by, users. It is therefore important that the transition from one system to another be managed effectively and efficiently. There are three perspectives on such a transition; those offered by:

information-systems methodologies

strategies for the management of change

strategic information systems planning.

Information Systems Methodologies

An information systems methodology is a methodical approach to information systems planning, analysis and design. A methodology involves recommendations about phases, subphases and tasks; when to use which and their sequence; what sort of people should perform each task; what documents, products, reports should result from each phase; management, control, evaluation and planning of developments. Information system methodologies have been developed by systems developers and designers as tools to aid in modelling information systems and designing a computer-based system that meets the requirements of the user of the information. The adoption of a systematic approach to information-systems development offers a number of advantages. Broadly the advantages for the manager include:

control over planning, since progress can be charted, and financial allocations can be predicted

standardized documentation which assists in communication throughout the systems planning and life

continuity provided as a contingency against key members of staff leaving the systems staff.

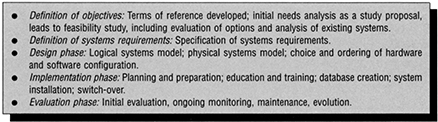

Although information systems methodologies vary, the following five main stages are common:

definition of objectives

definition of systems requirements

design

implementation

evaluation.

Figure 13.6 gives a more complete summary of some of the typical elements of such stages.

Managing Change

Figure 13.6 Summary of stages in systems analysis and design 376

The literature on the management of change recognizes that change will only be successful if people as well as systems change. Information systems have been one of the main levers for change within organizations as we move towards a knowledge-based society. For many systems users change is one of gradual evolution punctuated by occasional incremental change. Employees, and other users of systems, must feel able to adjust to systems change if they are to continue to create and use the databases upon which the organization of knowledge depends. Users will often have an opportunity to participate in systems changes. In order to allow staff and users to make a positive contribution in a change situation a manager must adopt an appropriate change strategy. Possible change strategies are:

Directive, where the manager makes a decision and indicates the direction in which he expects change to take place.

Normative, where the manager seeks to win the ‘hearts and minds’ of staff and to persuade them to share their vision of the positive value of change.

Negotiating, where bargaining in the form of: ‘if you do this, I will do that’, is employed.

Action centred, where change is tried and experimented with, and introduced on a step-by-step basis without necessarily defining the ultimate outcome in advance.

Analytical, where the best changes are identified by an expert, say, a consultant, and their advice is taken in selecting the changes.

These strategies have not been discussed extensively in the context of information systems, despite the fact that information systems either within the organization or outside have been responsible for much of the recent change in organizational structure, culture and market-place. This may be because, with information-systems implementation, it is always possible to resort to taking away someone’s old systems and presenting them with new systems so that they have no option but to use the new system. In this context it is relatively easy to adopt a focus on the Directive and Analytical strategies. However, without some application of Normative and Negotiating strategies there is not much chance that the user will use the system effectively, and enjoy the experience.

Strategic Information Systems Planning

Information systems methodologies are a useful tool at the individual project level. In recent years there has been a growing awareness that information systems planning within organizations should be integral to the organization’s strategic plan. This has led to developments in the approach to the management of information systems. This approach can be described as strategic information systems planning (SISP). Strategic information systems planning is the process of establishing a programme for the implementation and use of information systems in such a way that it will optimize the effectiveness of the organization’s information resources and use them to support the objectives of the whole enterprise as much as possible. The outcomes of an SISP are typically a short-term plan for the next 12 to 18 months, as well as a longer-term plan for the next three to five years. Strategic information systems planning has been evolving over the last ten years, fuelled by the recognition that the hardware/software approach to information systems planning was not producing results either for the information systems department or for the organization as a whole. Put very simply, it has become clear that information systems are so integral to effective management, that managers at all levels, including the very top, need to participate in information systems planning.

The central focus of SISP is the matching of computer applications with the objectives of the organization, so as to maximize the return on investment in information systems. Strategic information systems planning has a dual nature. It covers both detailed planning and budgeting for information systems at one level, and strategic issues and formulation at another. One of the characteristics of SISP is that in some cases it leads management to reassess the appropriateness of the enterprise’s objectives and strategies, and it has occasionally been known to lead to major strategic reformulation.

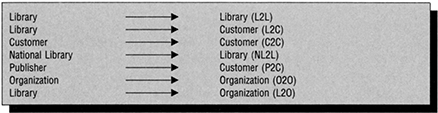

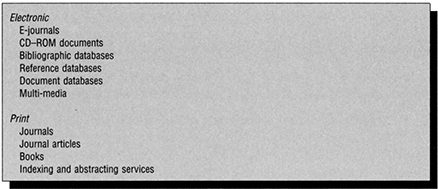

Organizations in Knowledge Organization and Delivery

The organization of knowledge is achieved through the activities of various information professionals, such as cataloguers, indexers, knowledge workers and others. These individuals are usually employed by organizations, such as libraries, library consortia, abstracting and indexing services, publishers, and Internet search engine providers. Libraries in particular have a long history of collaboration in their efforts to organize knowledge in order to preserve and develop the cultural heritage of our society. In Chapter 11 a number of the organizations that are involved in the organization of knowledge as database producers, publishers and online search services have been discussed. In general, the Internet offers an infrastructure, which supports a wide range of different types of document and information exchange. While these exchanges could be performed on an ad hoc basis, they are usually facilitated by the development of a range of relationships, otherwise described as a network. Such networks may comprise users, libraries, national libraries, publishers and a range of other agencies in the information industry. These relationships may be the basis for exchange of, or provision of access to, a range of databases and document types. Figure 13.7 summarizes the key relationship types and Figure 13.8 lists some categories of databases and documents that may be made available through the such networks.

Figure 13.7 Relationship types in knowledge networks

Figure 13.8 Document types covered by knowledge networks

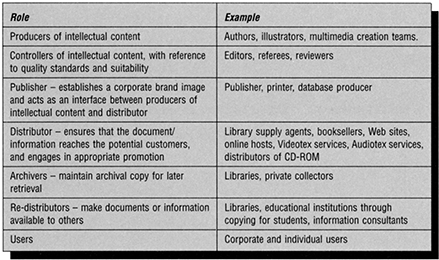

The ultimate aim of most networking is to make documents, information or knowledge accessible to the end-user. However, there may be a number of other relationships in the supply chain, which supports this end-user delivery, including in particular those roles concerned with document creation. Figure 13.9, for example, is a summary of the roles in document creation and delivery, and identifies some of the organizations and individuals that might adopt these roles in the electronic information market-place. It is perhaps particularly significant that some organizations and professional groups may be involved in a number of these stages or, to put it another way, may control several stages in the supply chain.

Librarians have long engaged in cooperative ventures, or networks and consortia. The early objectives of these networks were associated with exchange of catalogue records and print-based document delivery or interlibrary loan. These functions still remain important, but they are now facilitated by electronic exchange of records, and record keeping. Often, print document delivery has been supplemented by electronic document delivery.

Groups of libraries have maintained union catalogues for many years. The earliest union catalogues were large card catalogues whose creation was a labour of love and which were very difficult to keep up to date. Similarly, interlibrary loan arrangements existed between libraries long before the latest computer-based systems and data networks. However, under these arrangements, inter-library loan was often a slow process. Cooperation is generally seen as a means of sharing resources or containing cataloguing costs. In recent years, networks have increasingly become dependent upon telecommunication networks and computer systems. The first computer-based cooperative ventures, while ambitious for their time, would seem very basic now. Batch systems, with too much paper, little connectivity between processors and limited online access, predated the much more streamlined systems that it is easy to take for granted today. Systems have undergone major development since the late 1960s and early 1970s. Nevertheless, the central objectives of networking remain constant. These are to:

Figure 13.9 Stakeholder roles in the electronic information market-place

reveal the contents of a large number of libraries or a large number of publications especially through accessibility of catalogue databases, using OPAC interfaces

make the resources shown in these catalogue databases available to individual libraries and users when and where they need them

share the expense and work involved in creating catalogue databases through the exchange of records and associated activities.

Ancillary functions that might also be fulfilled by networks include:

distribution and publication of electronic journals and other electronic documents

end-user access to other databases, such as those available on the online search services and CD-ROM;

value-added services such as electronic mail, directory services and file transfer

exchange of bibliographic and authority records, usually in MARC format.

In the beginning networks were established with limited and well-defined objectives. As the use of networking has become more pervasive, and as the infrastructure has become available which makes data transfer more common, consortia and participants in consortia are likely to be linked to other consortia or members in consortia. The end-user can choose more than one route through the maze of networks in order to locate a given document. Barriers are already less defined by the physical limitations of networks than by licensing and access arrangements. Technology imposes few constraints, but politics and economics are beginning to define the boundaries.

The key agencies in library networking fall into two main categories:

Large national libraries or centralized cataloguing services which create large bibliographic databases and, in some instances, provide leadership in document delivery.

Cooperatives set up by groups of libraries who feel that they and their users can profit by resource-sharing, such as might be associated with interlibrary loans and document delivery, and sharing in the creation of a union catalogue database.

Developments in the USA

The USA is internationally significant in library networking, developments there will be reviewed first. Among the front-runners in US networking and responsible for much of the success of networking is the library of Congress. The Library of Congress first contributed to networking by acting as a centralized cataloguing service, and distributing printed catalogue cards, commencing in 1901. Experimentation with computer-based systems started in the 1960s with the MARC Project and led to the MARC Distribution Service. The LCMARC database is central to the Library of Congress’s cataloguing services. The database is based on the Library of Congress’s cataloguing of its own collections, with additional records from cooperating libraries. The database can be accessed online via a number of online search services. The Library of Congress has also played a major part in coordinating networking and has been involved in a number of projects that demonstrate its commitment to cooperation. Two major projects that merit mention are Cooperative Online Serials (CONSER) and the linked Systems Project (LSP). The CONSER was a cooperative venture, which sought to build a machine-readable database of serials cataloguing information. The LSP, started in 1980, aimed to establish a national network of services and utilities linked by a standard interface.

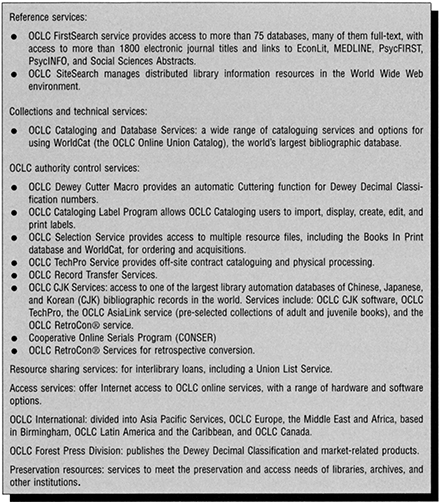

Another agency in US networking that has made a very major contribution is OCLC, founded in 1971 by a group of college libraries in Ohio. The OCLC has played a major role, both in the USA and beyond, in record supply, research and the sharing of experience. Its original acronym stood for Ohio College Library Center; it is now the Online Computer library Center. Currently over 33 000 libraries in 65 countries use OCLC services. The OCLC database is the largest catalogue records database in the world. Various services are related to the database; these are summarized in Figure 13.10.

Other networks in the USA and Canada include:

WLN, known previously as the Western library Network, and earlier as the Washington Library Network

RLG, or the Research libraries Group

UTLAS International, formerly University of Toronto library Automation System, is an important Canadian initiative.

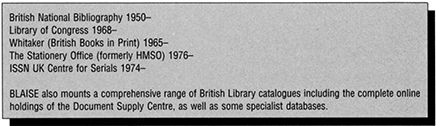

As in the USA, the first networking activities in the UK were associated with the centralized cataloguing service. The British National Bibliography, which is now the responsibility of the British library Bibliographic Services Division, was established in 1950. Initially BNB was a printed product that listed books received on legal deposit; since 1991 the main classified section contains two sections, a list of forthcoming titles and a list of titles recently received on legal deposit A MARC distribution service began in 1969, initially based on machine-readable versions of the records in BNB, referred to as the BNBMARC database. The BLMARC database now includes many other records generated by other sections of the British library. The British library Automated Information Service (BLAISE), is a major avenue through which BLMARC records may be accessed. Alongside these developments, the British library Document Supply Centre has established itself as one of the leading document delivery agents. The BLDSC supplies 4 million documents a year. Requesting is electronically through the BLDSC’s proprietary ART system, although requesting by e-mail is increasing. Requests by every route are stored in the Automated Request Processing, which streams them to the relevant document storage area. Journal articles are then picked from the shelves to be copied or scanned, or selected from the ADONIS electronic journal archive. The British library’s Digital Library Programme has a priority article alerting service and improved request and delivery from digital store.

Figure 13.10 Summary of OCLC services

Inside Science Plus and Inside Social Sciences and Humanities Plus jointly offer access to the contents of 20 000 journals. Electronic ordering of any articles retrieved from the database is possible. Delivery options include two-hour fax, courier and post.

The British Library’s Automated Information Service provides access to over 22 databases containing over 17.5 million bibliographic records. As an online search service access is available either using a command language, or using a GUI on the WWW. A direct link to the British Library Document Supply Centre means that customers can place orders for documents very easily. Figure 13.11 shows the bibliographic files that are available through BLAISE. These can be used for subject searching, bibliographic checking, acquisition, compiling booklists or record supply. The British library’s Automated Information Service also offers access to a number of specialist databases, and the catalogues of the British library collections.

Figure 13.11 BLAISE Bibliographic Files

There are also a number of library networks in the UK Two long-standing organizations are: BLCMP and LASER

Formerly known as Birmingham libraries Co-operative Mechanization Project, BLCMP is a cooperative venture that embraces a range of services that are used by a large number of libraries. The BLCMP maintains extensive MARC databases, which include records for books, audiovisual items, music and serials. An extensive authority file is also maintained. TALIS is BLMCP’s library management system. In 1999 BLCMP library Services Ltd ceased to be a cooperative and was renamed Talis Information Ltd.

The London and South East Region started life with a focus on interlending and resource sharing, rather than on cataloguing. Nevertheless, in order to achieve its objectives it built a large union catalogue, and later a bibliographic database. This is at the heart of LASER’S V3.0nline service, which provides access to this database and an electronic interlending system. A significant recent development led by LASER has been Electronic Access to Resources in Libraries (EARL). The EARL consortium of UK public libraries was established in 1995 to develop the role of public libraries in providing library and information services over the network. Its membership includes more than 50 per cent of UK public libraries. Examples of EARL initiatives include EARLWeb, a network of public library information resources, and a consortium purchase deal to OCLC’s Firstsearch service.

Exchange of expertise and plans for farther UK networking have also been fostered by a number of other groups, agencies and activities. The Consortium of University Research Libraries (CURL), for example, succeeded in creating a major machine-readable catalogue database, covering the catalogue records of the UK’s seven largest university libraries. The records are available for shared cataloguing and are distributed on tape, using file transfer and capturing session logs. The database is available to other libraries via JANET and via the more recently developed COPAC interface.

The Joint Academic Network (JANET) is not a library network, but a telecommunication network that provides communication links between users of computing facilities in over 100 universities, research establishments and other institutions. The JANET has been widely exploited by libraries for mutual access to library OPACs, and for file transfer and electronic mail. Gateways are available to other networks such as EARN (European Academic Research Network), Internet (US) and to public data networks.

Bath Information and Data Services (BIDS) is a service offered by the UK Office for Library Networking (UKOLN) which was established in 1989 with funding from the British Library; it is based at the University of Bath. The function of UKOLN is to support the development of networking activities among UK libraries by representing the needs of libraries to the computing and telecommunication industry, and promoting effective use of existing and developing networking infrastructures in the UK and abroad. The BIDS has played an important role in making electronic databases available at competitive rates within the UK academic community. Key databases are: BIDS ISI Service, BIDS EMBASE Service, BIDS COMPENDEX service, BIDS UnCover service and BIDS Inside Information Service. BIDS is unique in being one of the first national services to offer access to bibliographic databases free at the point of delivery.

The UK Pilot Site Licence Initiative, was instigated by the Joint Information Systems Committee of the Higher Education Funding Councils CISC). Pub-Ushers make their journals available to all universities and colleges throughout the UK, through their own servers. Access to the servers is provided by the JournalsOnLine service hosted by BIDS. JournalsOnLine provides Web access to a search form on which the user selects the publisher and enters the search strategy. The search is made against a headings file at BIDS, which is compiled from publishers’ data. On discovering useful documents, the user has the option of requesting them online and taking delivery online. The publishers store their electronic journals in PDF, which preserves the look of the printed counterpart when delivered to the desktop. This project finished in 1998 and is replaced by the National Electronic Site Licence Initiative (NESLI), which is seeking to establish a range of consortium licence arrangement with publishers which will provide access to electronic journals and other documents for UK academic libraries and their users.

Libraries have formed library cooperatives and networks for many decades. Such networks have played a major role in resource sharing and in the development of computerized library management systems. Networks in Europe and the USA, such as BLCMP, LASER, OCLC and WLIN have now been well established since the late 1960s.

Many established library network ventures were early participants in the investigation of potential for computerization and have been major proponents in the development and implementation of library management systems. Cooperation in recent years has been fuelled by the increase in volume of publications, expenses involved in obtaining them and new forms of publication.

Such networks have always been concerned with document delivery. Recently there have been a number of initiatives and projects associated with electronic document delivery. One example of this is the Ariel software, which was developed by RLG. Ariel is a document scanning and transmission system. The software resides on a PC running TCP/IP networking protocol and Windows GUI. It controls a locally attached scanner and printer and can sense and receive scanned documents via FTP. Records for interlending and document request are not dealt with by the system, and need to be separately managed. Ariel has been widely used between libraries within consortia. In the UK it was used in the LAMDA project, which involved four libraries from the M25 Consortium and five from the CALIM consortium. Version 2 of the software, released in 1997, included the option of transmitting documents as Multimedia Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) attachments to Internet mail. The work with Ariel has provided a platform for more ambitious projects that seek to integrate the whole process of information access, from discovery to delivery. Such projects place library consortia in direct competition with online search services. EDIL for example, identified the available mechanism for electronic document delivery, and informed the growing view that Internet standards and electronic mail are the most appropriate approaches to electronic document delivery. The EDDIS developed this further. This project developed an operational system in which users log into a local server, and the server manages access to remote databases and suppliers. Remote systems could be other EDDIS systems or any system that is EDDIS compliant, in the sense that it is implementing the same standards. The EDDIS is designed as an end-user service that integrates document discovery, location, request and receipt available through a WWW interface. In addition, it allows the librarian to control end-user activities transparently by configuring the system with library business policy decisions and by offering varying levels of mediation as part of the service. The local OPAC remains external to the server, along with remote OPAC’s and other bibliographic databases. The system might provide access to books and periodical articles in print and digitized form. Projects such as EDDIS have demonstrated that electronic document delivery is possible, but implementation depends upon an acceptance of standards and a critical mass of users. They also illustrate the centrality of the role of major libraries, special collections and library consortia in information access and document delivery.

Other Countries

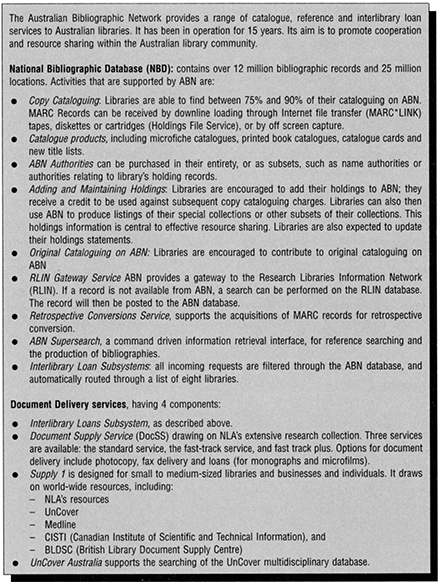

Similar roles are adopted by national libraries and consortia in other countries in the world. Figure 13.12, for example, summarizes some of the services offered by the National library of Australia and the Australian Bibliographic Network (ABN).

In conclusion, many of these consortia have made significant contributions to the realization of the electronic library, both through the continuing evolution of library management systems, and through the creation of large shared bibliographic databases which have contributed significantly to the reduction in original cataloguing. Currently such networks are serving as important focal points for developments associated with electronic document delivery, electronic journals and a variety of Web-based facilities which provide access to a wide range of other databases and information resources.

Summary

This chapter has explored a number of issues associated with the management of systems for the organization of knowledge and information retrieval. Evaluation is a key issue for the effective and efficient use of systems and systems development. Key evaluation measures are recall and precision. Evaluation has been conducted by systems developers, in respect of specific systems, and by researchers, in search of general principles that should guide system design. The databases to be searched need to be maintained and updated. Authority control over the form of names and subject terms helps to instil consistency into the database, and thereby assists with database quality. Other issues in the management of systems include maintenance, security and user support. Systems are dynamic; the evolution of systems needs to be managed. Information systems methodologies and other approaches to the management of change can assist in this context. There are many organizations that are involved in the organization of knowledge. Significant among these organizations are the national libraries and the library consortia or networks. These organizations make a significant contribution to the sharing of resources, and the sharing of the work associated with the compilation of databases that are an essential prerequisite to full access to the resources which can be accessed through a number of different libraries and other information providers.

Figure 13.12 Australian Bibliographic Network and the National Library of Australia

Further Reading

Organizations

Arnold, S. E. (1990) Marketing electronic information: theory, practice and challenges 1980–1990. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 25, 87–144.

Barker, R. (1994) Electronic libraries - visions of the future. Electronic Library; 12 (4), 221–229.

Barwick, M. (1997) Interlending and document supply: a review of recent literature - XXXII. Interlending and Document Supply, 25 (3), 126–132.

Basch, R. (1995) Electronic Information Delivery: Ensuring Quality and Value. Aldershot: Gower.

Batt, C. (1997) Information Technology in Public Libraries, 6th edn. London: Library Association.

Blunden-Ellis, J. (1997) LAMDA - a project investigating new opportunities in document delivery. Program, 30 (4), 385–390.

Boss, R. W. (1990) Linked systems and the online catalog: the role of OSI. Library Resources and Technical Services, 34 (2), 217–228.

Boyd, N. (1997) Towards access services: supply times, quality control and performance related services. Interlending and Document Supply, 25 (3), 118–123.

Bradley, P. (1997) The information mix: Internet, online or CD-ROM. Managing Information, 4 (9), 35–37.

Braid, A. (1996) Standardisation in electronic document delivery: a practical example Interlending and Document Supply, 24 (2), 12–18.

Brown, D. J. (1996) Electronic Publishing and Libraries: Planning for the Impact and Growth to 2003. London: Bowker-Saur.

Buckland, M. K. and Lynch, C. A. (1988). National and international implications of the Linked Systems Protocol for online bibliographic systems. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 8 (3/4), 15–33.

Castells, M. (1996) The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Cawkell, A. E. (1991) Electronic document supply systems Journal of Documentation, 47 (1), 41–73.

Cousins, S. A. (1997) COPAC: the new national OPAC service based on the CURL database. Program, 31 (1), 1–21.

Dempsey, L. (1991) Libraries Networks and OSI: A Review with a Report on North American Developments. Bath: UK Office for Library Networking.

Greenaway, J. (1997) Interlending and document supply in Australia: the way forward. Interlending and Document Supply, 25 (3), 103–107.

Grosch, A. N. (1995) Library Information Technologies and Networks. New York: Marcel Dekker.

King, H. (1995) Walls round the electronic library. Electronic Library, 11 (3), 165–174.

Landes, S. (1997) ARIEL document delivery: a cost effective alternative to fax. Interlending and Document Supply, 25 (3), 113–117.

Larbey, D. (1997a) Project EDDIS: an approach to integrating document discovery, location, request and supply. Interlending and Document Supply, 25 (3), 96–102.

Larbey, D. (1997b) Electronic Document Delivery. London: Library and information Technology Centre (Library and Information Briefing 77/78).

Lynch, C. F. (1997) Building the infrastrucutre of resource sharing: union catalogs, distributed search, and cross-database linkage. Library Trends, 45 (3), 448–461.

Morrow, T. (1997) BIDS and electronic publishing. Information Services and Use, 17 (1), 53–60.

Moulto, R. and Tuck, B. (1994) Document delivery using X.400 electronic mail. Journals of Information Networking, 1 (3), 191–203.

Report on Phase I of the Evaluation of the UK Pilot Site Licence Initiative. Bristol: Commonwealth Higher Education Management Service, April 1997.

Rowland, E., McKnight, C. and Meadows, J. (eds) (1995) Project EVLYN. London: Bowker-Saur.

Rowley, J. E. and Slack, F. S. (1998) New approaches in library networking: reflections on experiences in South Africa. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 31 (91), March, 33–38.

Smith, P., Stone, P., Campbell, C., Marks, H. and Copeman, H. (1997) EARL: collaboration in networked information and resource sharing services for public libraries in the UK. Program, 31 (4), 347–363.

Stone, P. (1990) JANET: A Report on its Use for Libraries. London: British Library Research and Development Department (British Library Research Paper 77).

Tuck, B. (1997) Document delivery in an electronic world. Interlending and Document Supply; 25 (1), 11–17.

Turner, F. (1995) Document ordering standards: the ILL protocol and Z39.50 item order. Library HiTech, 13 (3), 25–38.

Wiesner, M. (1997) EDI between libraries and their suppliers: requirements and first experience based on the EDILIBE project. Program, 31 (2), 115–129.

Systems

Crinnion, J. E. (1992) Evolutionary Systems Development London: Pitman.

Cutts, G. (1991) Structured Systems Analysis and Design Methodology, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell.

Harbour, R. T. (1994) Managing Library Automation. London: Aslib.

Hughes, M. J. (1992) A Practical Introduction to Systems Analysis and Design: An Active Learning Approach. London: DP Publications.

Lester, G. (1992) Business Information Systems, Vol. 2, Systems Analysis and Design. London: Pitman.

Mason, D. and Willcocks, L. (1994) Systems Analysis, Systems Design. Henley-on-Thames: Alfred Waller.

Pachent, G. (1996) Network ‘95: choosing a third generation automated information system for Suffolk Libraries and Heritage. Program, 30 (3), 213–228.

Remenyi, D. S. J. (1991) Introducing Strategic Information Systems Planning. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rowley, J. (1990) Basics of Systems Analysis and Design. London: Library Association.

Schuyler, M. (ed.) (1991) The Systems Librarian’s Guide to Computers. Westport, CT: Meckler.

Skidmore, S. (1994) Introducing Systems Analysis, 2nd edn. Manchester: NCC/Blackwell.

Vaughan, T. (1994) Multi-Media; Making it Work, 2nd edn. Berkeley, CA and London: Osborne McGraw-Hill.

Evaluation

Basch, R. (1991) My most difficult search. Database, 14 (3), June, 65–76.

Bates, M. J. (1988) How to use controlled vocabularies more effectively in online searching. Online, 12 (6), November, 45–56.

Bawden, D. (1990) User-Oriented Evaluation of Information Systems and Services. Aldershot: Gower.

Borgman, C. L., Hirsh, S. G., Walter, V. A. and Gallagher, A. L. (1995) Children’s searching behaviour in browsing and keyword searching online catalogs: the Science Library Catalog Project. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 46 (9), 663–684.

Buckland, M. and Gey, F. (1994) The relationship between recall and precision. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 45 (1), 12–19.

Clarke, S. J. and Willet, P. (1997) Estimating the recall performance of Web search engines. Aslib Proceedings, 49 (7), 184–189.

Cleverdon, C. W. (1967) The Cranfield tests on index languages devices. Aslib Proceedings, 19 (6), 173–194.

Cousins, S. A. (1992) Enhancing subject access to OPACs: controlled vocabulary versus natural language. Journal of Documentation, 48 (3), 291–309.

Felix, D., Graf, W. and Kreuger, H. (1991) User interfaces for public information systems. In H. Bullinge (ed.), Human Aspects of Computing. New York: Elsevier.

Fugmann, R. (1982) The complementarity of natural language and indexing languages. International Classification, 9 (3), 140–144.

Garzotto, F., Mainetti, L. and Padini, P. (1995) Hypermedia design, analysis, and evaluation issues. Communications of the ACM, 38 (8), 74–86.

Gordon, M. D. (1989) Evaluating the effectiveness of information retrieval systems using simulated queries. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 41 (5), 313–323.

Hancock-Beaulieu, M., Fieldhouse, M. and Do, T. (1995) An evaluation of interactive query expansion in an online catalogue with a graphical user interface. Journal of Documentation, 51 (3), 225–243.

Hill, S. (1995) A Practical Introduction to the Human-Computer Interface. London: DP Publications.

Hix, D. and Hartson, H. R. (1993) Developing User Interfaces: Ensuring Usability through Product and Process. New York: Wiley.

Karat, C. M., Campbell, R. and Fiegel, T. (1992) Comparison of the empirical testing and walkthrough methods in user interface evaluation. In P. Bauersfield, J. Bennett and G. Lynch (eds), Proceedings of ACM HCI ‘92 Conference of Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 397–404. Monterey, CA: ACM.

Kearsley, G. and Heller, R. S. (1995) Multimedia in public access settings: evaluation issues. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 4 (1), 3–24.

Keen, E. M. and Digger, J. A. (1972) Report of an Information Science Index Languages Test. Aberystwyth: Department of Information Retrieval Studies, CLW.

Keen, M. (1997) The OKAPI projects Journal of Documentation, 53 (1), 84–87.

Lancaster, F. W. (1969) MEDLARS: report of the evaluation of operating efficiency. American Documentation, 20 (2), 119–142.

Mizzaro, S. (1997) Televance: the whole history. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48 (9), 810–832.

Morley, E. T. (1995) The SilverPlatter experience. CD-ROM Professional, 8 (3), March, 111–118.

Robertson, S. E. and Beaulieu, M. (1997) Research and evaluation in information retrieval. Journal of Documentation 53 (1), 51–57.

Schamber, L. (1994) Relevance and information behavior. Annual Review of Information Science, 29, 3–48.

Su, L. T. (1992) Evaluation measures for interactive information retrieval. Information Processing and Management, 28 (4), 503–516.

Shneiderman, B., Brethauer, D., Plaisant, C. and Potter, R. (1989) Evaluating three museum installations of a hypertext system. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 40 (3), 172–182.

Slack, F. E. (1996) End user searches and search path maps: a discussion. Library Review, 45 (2), 41–51.