6

Pre-coordination and subject adadings

Introduction

Chapter 5 considered the principles of language control and the construction and use of thesauri. Here we are still concerned with language control. This chapter develops the idea of pre-coordination and its application in subject headings, where the approach is predominantly verbal. At the end of this chapter you will:

understand syntax in indexing languages

know the uses and limitations of post-coordination and pre-coordination

understand the importance of significance order and citation order in pre-coordinate systems

be aware of the development of subject heading theory and practice

understand the main features of the library of Congress Subject Headings

know some of the principal considerations in formulating subject headings.

In the previous chapter we suggested that a person’s natural inclination is to describe subjects in documents by means of title-like phrases: Laboratory techniques in organic chemistry, Skin diseases in dogs, and the like. These examples, and many others, are of compound concepts: in the language of information retrieval, they are pre-coordinated. However, thesauri as described in Chapter 5 deal in simple concepts only - laboratory techniques; organic chemistry; skin; diseases; dogs - and are designed for use with post-coordinate indexing and searching methods.

Verbal subject headings apply the principles of the thesaurus - controlled terms together with the semantic relations between them - to both simple and compound concepts. So verbal subject headings are pre-coordinate. Subject headings lists are lists of index terms, normally arranged in alphabetical order, which have been given authority for use in an index, catalogue or database for retrieving records by their subject content In manually searched indexes, the subject headings are used to file the records in alphabetical order. When these are interfiled with entries representing titles and authors in a library, the result is known as a dictionary catalogue.

Subject headings lists also make recommendations about the use of references for the display of semantic relationships, in order to (a) guide the cataloguer or indexer to the most suitable subject heading, and (b) guide users between connected or related terms.

Some writers on information access contrast thesauri with subject headings lists, others are more concerned with pointing out the similarities. The terminology is not chiselled in stone, however, and a number of thesauri have been designed for either post-coordinate or pre-coordinate use.

Syntax and Pre-Coordination

Pre-coordination is the combination of index terms at the indexing stage. The indexer constructs a heading containing as many terms as are required to summarize as much of the subject content of the document as the indexing system permits, and the searcher has to accept this heading in its entirety. This reflects and systematizes our natural tendency to think of subjects as phrases, like ‘Drug abuse treatment in Britain’. The LCSH for this topic is: Drug abuse - Treatment - Great Britain.

A pre-coordinate indexing system is one which, like LCSH, sets out to create compound headings - i.e., headings which may contain two or more elements or facets. Traditionally, two forms of manually searched index have used pre-coordination: dictionary and classified indexes. Also, library classification schemes are pre-coordinate systems. Older library classification schemes used pre-coordination intuitively, as does LCSH. All these are controlled language systems. Natural-language pre-coordinate systems are also found, mainly keyword in context (KWIC) indexes. (All these are described in Chapter 12.)

Pre-oordinate indexes are essentially for manual searching. By the time machine searching became the norm, and post-coordinate searching became the more usual way of accessing databases, pre-coordinate indexing systems were deeply and permanently embedded into many of our largest and most highly institutionalised bibliographic databases. Machine-searchable indexes (with a few exceptions) use inverted files to decompose subject headings, titles, etc. into their constituent keyword elements. These can then be searched individually, using the standard techniques of post-coordinate searching. For example, a record carrying the subject heading Drug abuse - Treatment - Great Britain would be retrieved by a search on any Boolean combination of individual words: ABUSE AND BRITAIN, and so on.

After specificity, pre-coordination is the most powerful device for improving the precision of a search - far more precise than the crude AND of Boolean searching. A few systems (MeSH, Compendex) permit limited preordination in a Boolean search. The method typically consists of applying a subheading to the descriptor for a system or organ (e.g., KIDNEYS - LESIONS). In natural language searching, phrase searching and the use of adjacency and proximity operators are forms of pre-coordination.

Pre-coordination is an aspect of the wider field of syntax: the study of the way we put words together to make sentences. Formally, syntax comprises the rules defining valid constructions in a language. These include rules for such elements as word order and punctuation, neglect of either of which reduces intelligibility. In the English language, a great deal of syntax is about word order: alter the order of ‘Dog bites man’ and you either reverse its meaning or create something unintelligible. Similarly with an indexing language. Here are two typical subject headings:

History-Teaching

Teaching - History

Anyone familiar with the English language coming across either would intuitively understand its meaning: the teaching of history, and the history of teaching. The syntax of indexing languages normally tries to eliminate prepositions and other link words (because they make for untidy filing). A few indexing languages include such link words systematically; their indexes are known as articulated indexes. They are described in ‘Facet analysis and subject headings’ in this chapter.

Significance Order

We all have well-organized minds, and tend naturally to think of the most significant elements of a subject first, and to establish a pecking order from the most important to the least important. This principle is fundamental to the way we structure knowledge in any medium, and can be seen, for example, in many onscreen menu trees. In most pre-coordinate systems, significance order is the basis on which index terms are combined, and is particularly important where:

a pre<oordinate system is in use and

La manual system of searching is in use and

items (citations or actual documents) are located in one place only.

These conditions are mainly to be found in:

library classification, where open access encourages users to browse the shelves

traditional printed and card catalogues, whether in dictionary or classified formats

the hard-copy versions of many bibliographies, indexes, and abstracts.

Significance order determines filing order. If a document was given the subject heading SOCCER - CUP COMPETITIONS, it would generally be far more useful if it could be sought in a filing sequence which included:

SOCCER - CUP COMPETITIONS

SOCCER - FRIENDLY MATCHES

SOCCER - LEAGUES

etc., than in a filing sequence which looked like this:

CUP COMPETITIONS - GOLF

CUP COMPETITIONS - NETBALL

CUP COMPETITIONS - RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL

CUP COMPETITIONS - SOCCER

CUP COMPETITIONS - TENNIS

etc. - a person is more likely to be interested in Soccer in all its aspects than in cup competitions across a range of sports. Also, anyone searching library shelves or ‘one place’ indexes, having noted the sequence SOCCER - CUP COMPETITIONS would reasonably expect the same pattern to be observed for items on cup competitions in other sports.

Significance order cannot be left entirely to intuition. The intuitions of two cataloguers in the library of Congress, presumably working separately and at different times, gave the world not only the heading Drug abuse - Treatment -Great Britain, but also Drug abuse - Great Britain - Prevention. A more systematic set of syntactic rules is needed if this kind of inconsistency is to be avoided. These rules are known as Citation order.

Citation order is the order in which the facets of a compound subject are set down (i.e., cited) in a pre-coordinate system. The elements may combine to make up a verbal subject heading or a classification notation. Traditionally, citation order has always been based on significance order. In making up a subject heading, as many of the facets are used as are required, or as the system permits (if the system in use does not permit facets to be combined freely), e.g.:

SOCCER - REFEREEING

SOCCER - CUP COMPETITIONS

SOCCER - CUP COMPETITIONS - REFEREEING

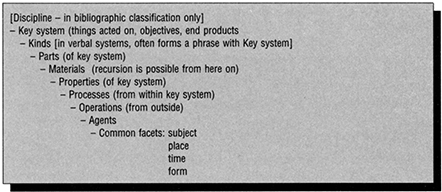

Figure 6.1 Standard citation order

The principles of citation order were largely evolved in the 1960s, and are based on the fundamental categories of facet analysis described in Chapter 5. Citation order also underpins the construction and use of library classification schemes, which will be described in the next chapter. The present section thus forms a bridge between Chapters 5 and 7.

The intention of ‘standard’ citation order was to form a set of readily understood and generalizable principles for determining facet sequence across all subjects. The elements of citation order are shown in Figure 6.1.

The following notes and comments are to be read in conjunction with Figure 6.1.

Discipline. General classification schemes all use discipline as their primary facet: e.g. in DDC the topic HORSES is expressed as Zoological sciences -horses (599.725), Animal husbandry - horses (636.1), etc. The descriptor in a verbal system (e.g. LCSH) would be, simply, HORSES.

Key system. A question-begging term for ‘whatever seems most significant’. Often it conveys the idea of purpose, end product etc. Key systems are always passive, and represent what is being influenced or acted upon. Examples: Testing the hardness of metals; Software packages for machine knitting; Group theory in physics; Road construction in developing countries; The conquest of California by the USA A key system in one context may not be so in another: e.g. MAPS is the key system of the topic The cataloguing of maps; but if the topic had been The cataloguing of maps in university libraries, then the key system would be UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES, and MAPS would be Materials.

Kinds. Whatever differentiates a term (focus), e.g. PORTABLE PRINTERS where PORTABLE differentiates such printers from other printers. Most alphabetical systems now treat these semantically, i.e. they would use the single heading PORTABLE PRINTERS. (Technically, PRINTERS is known as the focus and PORTABLE the difference.) A classification system on the other hand would differentiate printers by establishing subfacets:

Printers

(by portability)

(by method of operation)

(by colour)

fixed

ink-jet

monochrome

portable

laser (etc.)

colour

Parts. These are often treated semantically (i.e. using BT and NT). Here we are concerned with those instances where the part is not unique to the whole, and so has to be entered syntactically in pre-coordinate systems, e.g. GARAGES - DOORS. As well as physical parts, this category includes constituent parts, e.g. Recruitment of personnel to the Civil Service.

Materials. These are fairly self-explanatory, e.g. Glass for windows; though in practice this category is often subsumed under Kinds or Parts, and in verbal systems is often treated as a phrase (STEEL DOORS). (Recursion is the programmer’s term for a procedure which calls itself, as in the tale of the fairy who grants you two wishes. Your first wish is to be granted two wishes… The point here is that it is possible to have kinds of materials (GALVANIZED STEEL DOORS), parts of materials, etc.; and the same applies to the facets which follow: e.g. an agent can have kinds, parts, etc.)

Properties. Whatever qualities a key system possesses, e.g. Testing the hardness of metals; The development of reading skills in children.

Processes. These occur within the key system, and do not require any external agency: e.g., Diseases of mice, Development of reading skills in children.

Operations. These imply an agent (which need not always be named), e.g., Coaching children in reading, The conquest of California by the USA, Road construction in developing countries.

Agents. The agent or instrument which carries out an operation, e.g. Roundworms as vectors of virus diseases in potatoes; The marketing of prepackaged consumer goods by multinational companies, The conquest of California by the USA.

Common facets are concepts that are applicable to a wide range of topics. Most pre-coordinate indexing systems have lists of such concepts, so they can be tacked on to the end of a heading. They may be:

- subjects like Research or Psychology, which exist as disciplines in their own right, but are also applicable to any subject.

- places, where they limit the context of a topic (e.g., Road construction in developing countries)

- time, often a more restricted view of the common subject History (e.g., The conquest of California by the USA, 1846-1850), but sometimes including other temporal concepts (e.g., weekly).

- form, a catch-all which includes physical form (e.g. videos), literary form (e.g. poetry), and form of presentation (e.g. manuals) or arrangement (e.g. dictionaries, tables, programmed texts). They are most closely associated with headings for use in library catalogues and bibliographies of books.

As with fundamental categories, citation order often has to be adapted to the subject in hand, particularly within the humanities and social sciences. For example, in Education it is generally agreed that the key system is the Educand: the person being taught. However, in the literature of education it is not always easy to distinguish the Educand from the schools and colleges where education takes place. Some systems regard them as one; others distinguish them. The next most important facet concerns what is taught, i.e., Curriculum subjects, which correspond nearly enough to the generalized Materials facet. Under Processes we can subsume Student learning, but Teaching implies an Agent (the Teacher), so it is more properly an Operation; but teaching and learning are not always distinguishable in the literature.

Limitations of Pre-Coordination

There are six possible ways to arrange a subject string containing three elements (3 x 2 x 1); a five-element string can be arranged in 125 different ways. Therefore, in pre-coordinate systems, strings become exponentially more difficult to handle as the number of elements in them increases. More generally, they require more intellectual effort at the input stage, and are therefore costly to produce. They make too for bulky indexes, as they create cumbersome networks of references; and unless the index is ‘articulated’ (i.e. includes linking words such as for’, ‘in’, ‘of etc. to clarify relationships), a long subject string can be difficult to interpret. Thus the exhaustivity possible with pre-coordinate systems is low, and they can only operate at the level of summarization.

In practice, many systems limit the amount of pre-coordination they permit The following degrees of pre-coordination can be found:

Heading + single subheading, e.g. FOOTBALL - INJURIES. Examples: Index medicus (MeSH); Engineering index (Compendex). Here, pre-coordination is essentially a means for improving precision in post-coordinate searches.

Heading + a variable number of subheadings, but rarely exceeding three facets in all. Examples: any catalogue or index based on the LCSH or the DDC. Also most H. W. Wilson indexes, e.g., Cumulative Book Index, Library Literature.

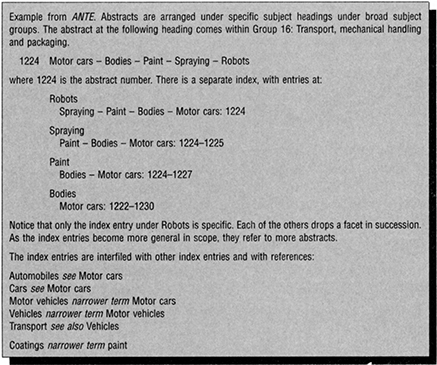

Fully faceted systems, allowing complete flexibility to express complex subjects. Examples: the PRECIS system, used to index the British National Biography (BNB) between 1971 and 1990; the revised BC2; Abstracts in New Technology and Engineering (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts -ASSIA - uses the same system).

Who Needs Pre-Coordination?

Citation order is important in that it determines the degree of collocation and scattering in one-place pre-coordinate systems. In particular, it is (after Discipline) the second most important factor affecting the physical ordering of items on library shelves. As machine searching of indexes has become the norm, the importance of citation order in indexes has diminished. Pre-coordination is important only in the printed versions of indexes; and most indexing and abstracting services now regard their hard-copy formats as incidental by-products of the machine-held database. Their indexing systems are often designed primarily for online searching, and users of the printed versions are left to manage as best they can with indexes that are relatively unsophisticated.

Another inherent problem with pre-coordination is that the searcher has to make do with the sequence of topics imposed by the system’s citation order. To some extent, multiple entry indexing systems can alleviate this problem. These, however, are inherently bulky, and unsuited to all situations - in particular they cannot be applied to shelf classification. A classification scheme that is sensitive to its users can provide alternative citation orders to serve the needs of different users. For example, DDC permits law books to be arranged by jurisdiction within broad topic headings (i.e. Broad topic - Jurisdiction - Problem), rather than by the preferred citation order, which is Broad topic - Problem - Jurisdiction. Another measure is the differential facet: part of a subject being treated differently from the rest. Thus in DDC curriculum subjects are distributed around the classification, using standard subdivision - 071, giving (e.g.) Mathematics teaching 510.71. This reflects the fact that in secondary education and above, subjects are taught by specialist teachers. This does not hold in elementary (primary) schools, however, where class teachers are normally responsible for all subjects. DDC recognizes this by classing elementary education in specific subjects within elementary education (372), at 372.3-372.8, e.g., Mathematics at 372.7.

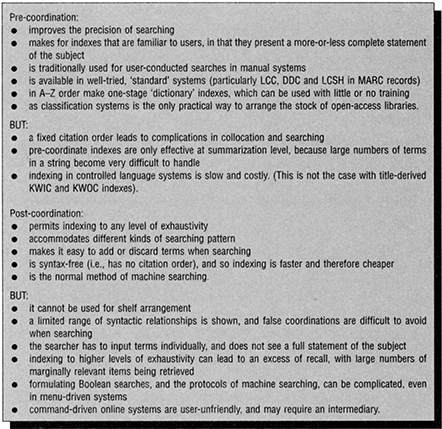

A summary of the relative merits of pre-coordinate and post-coordinate techniques is given in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2 Summary of pre-coordination and post-coordination

Traditional Cutter-Based Subject Headings Lists

Verbal subject headings began to be systematized well over a century ago, in 1876, when Charles Ammi Cutter published his Rules for a Dictionary Catalog (Cutter, 1904). Cutter’s system was as much of an advance on preceding systems as was Melvil Dewey’s Decimal Classification (which also dates from 1876; see Chapter 8 for a full discussion and listing of editions etc.). Around the turn of the century, the Library of Congress thoroughly reorganized its cataloguing procedures, adopting and developing Cutter’s Rules, and inaugurated its printed card distribution service. Its dictionary catalogue, based on Cutter’s principles, was quite simply the best available at the time. Library of Congress Subject Headings has continued with only evolutionary alterations (most of them since 1975) until the present day.

Cutter’s Rules thus still retains its relevance (as well as its readability). Cutter lists among the objectives of a catalogue:

To enable a person to find a book of which the subject is known; and

To show what the library has on a given subject and in a given kind of literature.

The techniques used to achieve these ends are:

Subject entry under the most specific word or phrase expressing the subject. In Cutter’s words: ‘Put Lady Cust’s book on “The cat” under CAT, not under ZOÖLOGY or MAMMALS, or DOMESTIC ANIMALS.’ This establishes the principle of alphabetico-direct as opposed to alphabetico-classed entry. Many catalogues and indexes of the time used the method known as alphabetico-classing, where subject entries display two or more hierarchical levels, a broad topical heading with a specific subheading, like DOMESTIC ANIMALS - CATS.

A work may have two or more subject entries if the subject cannot be fully specified in one. Composite subjects were less prevalent in Cutter’s day. Cutter did not recognize subheadings: a work on social conditions in rural England might have entries under SOCIAL CONDITIONS, RURAL CONDITIONS and ENGLAND. This principle is still to be found in LCSH: while subheadings are permitted there, such a work would now have the headings ENGLAND - RURAL CONDITIONS and ENGLAND - SOCIAL CONDITIONS.

The wording of subject headings must reflect usage. Cutter selected headings on the basis that they should be terms in general usage and accepted by educated people. In addition to problems with new subjects that lacked accepted or established names, this guiding principle engendered inconsistency in the form of headings. Equally, Cutter’s devotion to natural language posed problems with multi-word terms. Direct order was preferred, but inverted phrases were acceptable when it could be established that the second term was definitely more significant, leaving it to the individual to judge when to apply this. The well-intentioned vagueness of these rules has been inherited by LCSH.

A uniform heading for each subject, with references from synonymous terms. This technique states for once and for all the guiding principle of vocabulary control and, together with specific entry, is Cutter’s most lasting contribution to indexing theory and practice.

See also references Unking related subjects. While Cutter’s system of references has been refined, the main features of semantic relations are clearly laid down.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Library of Congress Subject Headings is the preeminent authority list for subject headings. First published in 1909, it is used not only by the Library of Congress but widely throughout the English-speaking world. The headings form the verbal subject approach in USMARC records and also in UKMARC records since 1997 (and sporadically before then), as well as in centrally produced records from Canada, Australia and some other countries.

Structure and Application

Library of Congress Subject Headings is firmly based on Cutter’s Rules for a Dictionary Catalog. The most important developments of Cutter to have been introduced by LCSH are subdivided headings and the use since 1988 of the thesaurus conventions BT, NT etc. to express semantic relationships in place of Cutter’s see, x, see also and xx.

Library of Congress Subject Headings was developed well before modern ideas about thesaurus construction were developed. It has been tidied up considerably since the mid-1980s in the light of modern theory, but is still full of inconsistencies. Like DDC, it is so well entrenched in library practice that it is unlikely to be replaced for many years. Paradoxically, online searching and OPAC have made LCSH more effective, as keyword access has ironed out many of its inconsistencies.

It is well to remember that LCSH is the head of a large family of subject heading systems derived from Cutter and sharing the same principles. Other examples include Sears List of Subject Headings - virtually an abridgement of LCSH - and the subject headings used in the various indexes published by the H. W. Wilson Company.

Types of Heading

Most headings are mapped to their equivalent LCC class numbers. The simplest form of heading is a single noun, e.g. Advertising; Heart; Railroads; Success.

A heading may be followed by a parenthetical qualifier, usually to distinguish homographs e.g. Cold (Disease) or explain terms not widely known, e.g. Dodoth (African tribe). Some qualifiers simply limit or qualify their heading by discipline, e.g. Divorce (Canon law); Bread (in religion, folk-lore, etc.) - the precise form of the qualifier can vary. A few, like Cookery (Chicken), are idiosyncratic forms of pre-coordination.

Phrase headings will usually be in direct order, often Adjective + Noun, e.g. Nuclear physics; American drama; Mining machinery. Other examples are: Children’s art; Chevrolet automobile (LCSH does not always follow thesaural recommendations as to singular and plural); and the notorious One-leg resting position (used once only, for a 28-page pamphlet published in 1942). Occasionally, following Cutter’s (1904, p. 69) instruction that phrases may be inverted ‘where the second term seems decidedly more significant’ we find such headings as: Education, secondary and Functions, Abelian - unfortunately the headings Adult education and Bessel functions also occur. Editorial policy is to reduce the number of inverted headings, and many have been eliminated: e.g. Gas, Natural has become Natural gas.

Conjunctive phrase headings link overlapping topics by means of ‘and’ or ‘etc.’, e.g.: literary forgeries and mystifications; Mines and mineral resources; Law reports, digests, etc. As well as being used for the conjunction of A and B, this type of heading can also be used to express a relationship between A and B, e.g.: Good and evil; Television and children; literature and society. Because of their inherent looseness, this type of heading has now been discontinued and some headings simplified, e.g.: Cities and towns, Ruined, extinct, etc. is now simply: Extinct cities.

A final form of heading is the prepositional phrase heading, e.g.: Fertilization of plants; Radar in speed limit enforcement; Automobile driving on mountain roads; Cooperative marketing of farm produce; Mites as carriers of disease; Bread in literature.

Headings for named entities - persons, families, places, corporate bodies - are established where possible in accordance with AACR2, and can usually be checked in the Name Authority File, as LCSH lists them only sporadically. To this extent, LCSH is an open system, allowing individual users to create headings for named entities.

Many headings have scope notes. These usually start with the formula ‘Here are entered works…’, and go on to define or explain the heading, indicate its application, and often to indicate the line of demarcation with related headings.

A heading may be a topical heading (what the work is about) or a form heading (indicating the work’s physical form or its form of presentation and arrangement). A heading such as Short stories might apply to a collection or to a work of criticism. In some but not all cases a subdivision may clarify which is which.

Subdivisions

The subdivision of headings is LCSH’s principal advance on Cutter, and the pre-coordination they provide greatly increases the precision of headings. Subdivisions are introduced by a hyphen. A large number of subdivisions are enumerated under their headings, but many more are designated free-floating. These are commonly used subdivisions which can be added to headings as required, and do not appearing specifically after their headings in LCSH. They can be of general or restricted application. There are around 40 different categories of these latter. They are controlled by pattern headings (i.e. representative headings for personal names, other proper names, various ethnic and national topics, and certain everyday objects, and serving as a pattern for all entries of the same type). Subdivisions are of four types: topical, form, geographic, and period.

Topical (i.e. subject) subdivision, often follows standard citation order, e.g.: Heart - Diseases; Herbicides - Research - Technique; Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616 - Characters - Children. There are (as always) anomalies: Automobiles - Motors - Carburetors (Thing - Part - Part) looks suspiciously like alphabetico-classing. (English readers should note both the terminology and the spelling. UKMARC records take LCSH as it comes, with no concessions to British English.)

Form subdivisions are the everyday common facets denoting common subject or form, e.g.: Engineering - Dictionaries; Mathematics - Study and teaching; France - History - Revolution, 1789-99 - Fiction; Suffolk - Description and travel - Guidebooks.

Geographic subdivisions are the common facets of place, e.g.: Probation -Northern Ireland; Music - England - Manchester; Geology - England - Peak District; Churches - England - Suffolk - Guidebooks. ‘Indirect’ subdivision (the name of the place is preceded by the name of the country in which it is situated) is often used for places smaller than a country to improve collocation.

Period subdivisions are the common facet of time. Mostly however they are not free-floating but are tailored to their topic (DDC often behaves in much the same way), e.g.: Great Britain - History - to 1485; Great Britain - History -Victoria, 1837-1901; France - Politics and government, 1589-1610; English fiction - nineteenth century; English drama - Restoration, 1660-1700; English language - Dictionaries - Early works to 1700. Occasionally, period is expressed in ways other than by a subdivision, e.g.: Art, Renaissance.

It will be seen from the above examples that more than one subdivision may be applied. There are usually specific instructions for particular combinations, to maintain control over the use of subdivisions. Recent policy has been to replace subdivisions with a phrase heading if possible, e.g., Railroads - Stations has become Railroad stations. In the application of subdivisions the following should be noted:

Order of heading and subdivision. Most headings conform to standard citation order (Entity - Action or process), e.g.: Kidneys - Diseases; but with occasional exceptions, e.g. Advertising - Cigarettes, which places the process before the product, presumably on the grounds that advertising is advertising whatever the product.

Topic versus Place. Usually topic comes first; but there are many occasions, particularly in the social sciences, where place takes precedence. To confuse matters further, cities are treated differently from regions, e.g. Nottingham (Notts) - Hospitals; but Hospitals - Nottinghamshire.

Geographic names may serve as headings, as part of a heading, as a subdivision, or as a qualifier, e.g.: Manning Provincial Park, BC; Jamaica - description and travel; Paris in literature; Building permits - Belgium; Japanese in San Francisco.

The filing sequence of headings and subheadings in card indexes and printed lists can be complex. An example appears in Figure 12.2.

Revision of Headings

A new edition of the printed LCSH appears annually, and now extends to five volumes. It is available in other formats, notably as part of the Cataloged Desktop CD-ROM. There is a weekly computer tape distribution service of new and changed headings, a cumulated file of which is accessible on the library of Congress’s (LC’s) Web site. There are also various printed and fiche lists. CDMARC Subjects is a quarterly CD-ROM update of the complete subject authority file. The L.C. Cataloging Service Bulletin gives information on selected new and cancelled headings.

Editorial policy has always been to create new headings as needed. Because of varying editorial policies stretching back for nearly a century, there are many inconsistencies in the formulation of headings. Where there has been a change of policy, normal practice was to leave existing headings alone, and apply the new policy only to headings established after the change of policy, with retrospective revision undertaken only when the pressure to change became intolerable, as when Negroes was changed to Blacks, or Electronic calculating machines to Computers. This conservatism was understandable and indeed necessary with card catalogues. Now that increasingly software is able to accommodate global changes to the catalogue database, current practice is to replace headings systematically.

References in Lcsh

The former reference symbols See, x, sa and xx have since 1988 been replaced with:

USE |

|

UF |

Used for |

BT |

Broader topic |

NT |

Narrower topic |

RT |

Related topic |

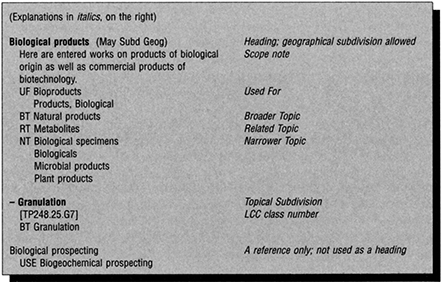

Library of Congress Subject Headings’s references (see Figure 6.3) have been tidied up considerably in recent years. The symbols follow thesaural practice, and denote Equivalence, Hierarchical and Associative relationships. Note however the subtle use of topic (acknowledging that some headings are pre-coordinate) instead of term (which in a thesaurus normally indicates a simple concept).

SA (see also) is still used, but is limited to general references. The following general reference appears under the heading Bibliography:

SA names of literatures, e.g. American literature; and subdivision Bibliography under names of persons, places and subjects; also subdivision Bibliography - Methodology under specific subjects, e.g. Medicine - Bibliography - Methodology; and subdivision Imprints under names of countries, states, cities, etc.

References are used in two ways. The cataloguer uses the references in the List to help locate the correct heading. References to headings in a catalogue or bibliography are interfiled with the headings. The catalogue user uses the references to help locate the correct heading for a topic; also as a means of moving between related topics. This use of references is becoming obsolete. It was normal usage with card and printed catalogues and bibliographies; but it is very unusual to include references in computerized catalogues and bibliographies (whatever their format)

Figure 6.3 LCSH heading with its references

Facet Analysis and Subject Headings

Library of Congress Subject Headings and other subject headings lists are known as enumerative systems. They are thus named because many headings - Fertilization of plants, and Radar in speed limit enforcement are two examples among many - list, or enumerate, compound topics in an ad hoc way, without system. So, for example, Fertilization of plants is not matched by any corre sponding heading for (say) the fertilization of roses; and there are no corresponding headings for the use of cameras or police helicopters to dis courage motorists from exceeding speed limits.

Developments since Cutter in the theory and practice of subject headings have largely taken place outside the USA, where the authority and wide availability of library of Congress printed cards discouraged experimentation. In England, J. Kaiser’s Systematic Indexing, published in 1911, suggested that many composite subjects can be analysed into a combination of a ‘concrete’ and a ‘process’; for example, SHIPS - SERVICING to represent the topic The servicing of ships’. While Kaiser made an important contribution to the development of citation order in subject headings, his work had little influence for nearly half a century.

In the late 1950s E. J. Coates took Kaiser’s work as his starting point, and combined it with the contribution to classification theory of S. R. Ranganathan. Ranganathan was the first to fully articulate the analytico-synthetic principle. This is the process of facet analysis (described later in this chapter) by which a summarization of the subject content of a document is analysed into its constituent facets, which are then synthesized into a subject heading according to the rules of whichever indexing language is being used. He also developed the theory of fundamental categories and citation order with his PMEST (Personality - Matter - Energy - Space - Time) formula, and devised chain procedure for organizing subject indexes to files of citations. Coates further developed facet analysis and applied it to subject headings. For over 30 years from 1963 Coates’s theories on the construction of subject headings and their references - expounded in his book Subject Catalogues (Coates, 1960) - were put into practice in British Technology Index (BT1), of which Coates was editor. They were sub sequently applied also to Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts and to BTTs successor Current Technology Index, now Abstracts in New Technology and Engineering (ANTE). Unlike Cutter and LCSH, Coates held that headings should be coextensive with a summarization of the subject. Multiple subject headings were, and are, forbidden. As the system is used to index technical subjects, some headings assume a daunting complexity. One knack is to read them backwards, inserting prepositions as required. The following are examples of subject headings as structured by Coates and his successors:

Steel, Low alloy: Welding, Electron beam

Piles; Concrete, Bored: Testing: Ultrasonics

Motor cars - Bodies - Paint - Spraying - Robots

Compact video discs - Image compression - Decoding - Multimedia microcomputers - Window systems - Replay systems - Expansion cards

The system has historical importance as the first large-scale working example of the use of computers to manipulate subject strings. It had some interesting subtleties - notice the use of punctuation as role indicators in the first two examples: commas introduce kinds, and semicolons materials. (The third and fourth examples show current practice, which is not to use differential punctuation.)

Articulated Subject Indexes

Articulated subject indexes have had some popularity as a less formal and intimidating technique than Coates for computer-generated subject indexes. Articulation means the insertion of link words into subject headings in order to bring them closer to natural language. Articulation is a purely syntactic device. It is for individual users to decide whether or not to employ a controlled vocabulary.

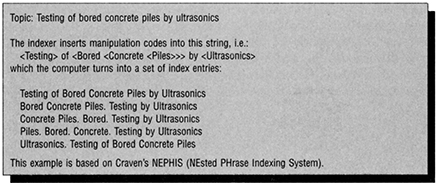

In an articulated subject index, the entry consists of a subject heading and a modifying phrase; these can be combined to form a title-like phrase. Modifying phrases are arranged alphabetically under a subject heading. The words or strings of words may be machine selected or drawn manually from a controlled vocabulary. The structure of the phrases is analysed, and various connectives and prepositions cause the generation of different arrays of entries. Note that prepositions are retained in the index. Figure 6.4 gives an example of string manipulation to form a set of articulated subject index entries.

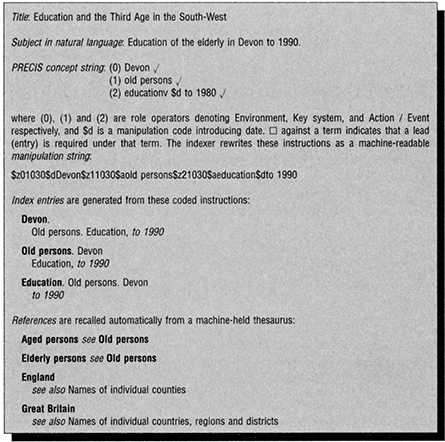

Precis

Coates’s BTI helped pave the way towards a new system of subject indexing that was to serve UKMARC records well for twenty years from 1971. The development of MARC in the late 1960s forced the British National Bibliography to rethink its indexing policies. Hitherto it had based its indexing on a locally expanded version of DDC. However, irregularities in the structure of DDC made it unsuitable for the machine generation of subject index entries, and the lack of specificity of a classification whose primary purpose was (and is) shelf arrangement was held to be inimical to good indexing practice. Additionally, good indexing practice was felt to require a more friendly and explicit procedure than chain indexing.

Figure 6.4 Articulated subject index

A completely new indexing system was therefore commissioned. The criteria laid down were that the system was to be based on a single coherent logic. The indexer was to produce, by intellectual effort, an input string of terms and role operators. The generation of index entries from this string, and any other subsequent operations, were to be computerized. Each entry under every significant word in the string was to provide a full subject statement - unlike LCSH, and unlike Coates’s system also, where only one entry was coextensive with the subject, access from other terms being by references. Entries were to be as close as possible to natural language. Finally, the new system was to make a firm distinction between semantic and syntactic relations (chain procedure linked to a classification schedule is unable to distinguish them), and was to have a machine-held thesaurus that would automatically produce see and see also references to the terms in each string. Effectively, what was to be devised was an articulated subject indexing system having a controlled vocabulary.

The result was called Preserved Context Index System (PRECIS). Its syntax is based on a system of over 30 role operators and other manipulation codes. These have three functions. They indicate the role of each term within the subject statement or string. They determine the citation order. Finally, they pass instructions to the computer for the precise pattern of rotation of the index entries under each lead term, as well as their typography, punctuation and capitalization.

Figure 6.5 PRECIS worked example

Figure 6.5 shows a fairly simple subject string; the system is capable of far greater complexity. While indexes produced by PRECIS are models of clarity and precision, the system was essentially designed for printed output and manual searching. With the move to machine searching, it became difficult to justify the costly complexity of formulating input strings, and UKMARC records now use LCSH as their only means of controlled language subject access.

PRECIS is an example of an open indexing system. Many indexing systems are closed: that is, individual users have no autonomy to add new headings as required, but have to wait until the next official amendment list from the system’s compilers or other responsible authority. Any system with a classified display is likely to be closed, as new headings have to be inserted into their correct classified position. PRECIS as a purely alphabetical system simply sets out the rules for the construction of headings and references, and allows users to construct and maintain their own authority files.

Access From Subordinate Terms in Subject Headings

Many subject headings consist of a single concept only, but many more contain two or more concepts, or facets. In machine-searched systems any facet is equally retrievable, but manually searched indexes need to provide some mechanism for gaining access from terms that are not in the lead (filing) position. Most indexes employ some form of rotation: a subject heading consisting of the facets ABCD, and filed at A, can also be retrieved by means of references or additional citations at B, C and D.

There are a number of different ways of rotating subject headings. All of the following are commonly found in indexes:

Cycling; Successive index entries move the final term across to the lead position:

Football. Clubs. Management Scotland.

[citation or address]

Management Scotland. Football. Clubs.

[citation or address]

Clubs. Management. Scotland. Football.

[citation or address]

Scotland. Football. Clubs. Management.

[citation or address]

Keyword out of Context (KWOC). With this technique (which has many variations) the lead term is followed by either the whole of the string, or (as in the example) the remainder of the string:

Football. Clubs. Management Scotland.

[address]

Clubs. Football. Management. Scotland.

[address]

Management Football. Clubs. Scotland.

[addresss

Scotland. Football. Clubs. Management.

[address]

Rotation, or Keyword in Context (KWIC). The whole string is slid forward in successive index entries, so that each term in turn appears in the lead position:

Football. Clubs. Management Scotland. [address]

Football.

Clubs. Management. Scotland, [address]

Football. Clubs.

Management Scotland. [address]

Football. Clubs. Management.

Scotland, [address]

Shunting. This method is used by PRECIS, and has a two-line format:

Scotland. Football. Clubs. Management

[citation or address]

Football. Scotland. Clubs. Management.

[citation or address]

Clubs. Football. Scotland. Management.

[citation or address]

Management Clubs. Football. Scotland.

[citation or address]

(PRECIS determines citation order by context dependency; hence the different ordering of the string.) KWIC and Shunting preserve the citation order of the original string; other methods based on rotation distort the citation order. This can occasionally cause relevant entries to be overlooked when conducting a manual search. To counteract this, some have suggested permutation: creating references under all possible combinations of the facets. This however is prohibitively bulky: a four-facet string would generate 24 references (4! factorial 4, i.e. 4x3x2x1). There is a modified form of permutation called Selective Listing in Combination (SLIC), which bears a similar relationship to permutation as chain procedure (see below) does to rotation. Even this generates an unac-ceptably large number of references.

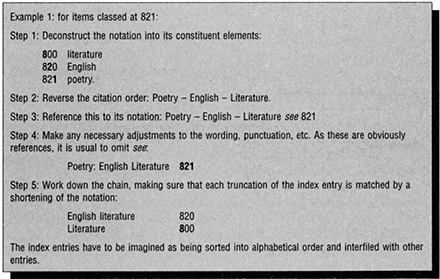

Chain Procedure

Rotated indexes are usually generated by computer program. Chain procedure was originally devised by Ranganathan as an economical method for the manual production of subject indexes, but it is equally amenable to computer-generated indexes. It became popular in Britain in the 1960s as an economical method of organizing the subject indexes to classified library catalogues, and so was often adapted for use with DDC. The essentials of this will be described below. However, chain procedure in its original and purest form uses verbal headings alone. We will use the same subject heading as in the previous examples:

Football. Clubs. Management Scotland.

This heading would be Mowed by a citation. Every other approach is a reference:

Scotland. Management. Clubs. Football, see Football. Clubs. Management Scotland.

Notice that the reference reverses the order of the original string. Then, each successive reference truncates the string by removing its last facet (the first facet of the back to front string):

Management Clubs. Football, see Football. Clubs. Management. Clubs. Football, see Football. Clubs.

The reference under Management has dropped Scotland, so that the reference can be used as it stands for items on the management of football clubs in England, Milan, or wherever, as well as for the management of football clubs generally. In the same way, the reference

Clubs. Football, see Football. Clubs.

will serve for items on all aspects of football clubs, and not just their management.

This describes the original system of references. As it was rather bulky, it has subsequently been simplified (Figure 6.6).

Again, observe in the above example that (a) the references reverse the citation order of the heading, and (b) each successive reference drops a facet, so that only the first reference is specific to the subject. Note that until the reference is followed up, the searcher does not know exactly how detailed the subject is; and what looks like a reference to a general topic may lead only to an item on one small aspect of it. This situation happens all the time with post-coordinate searches, where searchers are aware that they are working with keywords, and the actual searching is done by computer. Searchers are therefore less likely to mind if their search yields a highish proportion of dross along with the nuggets. Greater precision is usually expected with manual searching, however, as it is far more laborious; and pre-coordinate headings look as if they ought to mean what they say, so that searchers are rightly disappointed if they find that they do not This is a typical instance of greater recall in a search leading to loss of precision.

Figure 6.6 Subject index by chain procedure

Chain procedure and the classified catalogue

The adaptation of chain procedure to the classified catalogue relies on classifications like DDC having a notation that is largely hierarchical. The technique was widespread from the 1960s on in Britain, where the great majority of libraries of all kinds had classified catalogues; and there are still many library catalogues, including OPACs, whose subject indexes are based on (or at least pay lip-service to) chain indexing. The technique is described in Figure 6.7.

A big limitation of this method when applied to DDC is that the classification is often too inflexible to express all facets of a subject. The nearest that DDC can get to the Football example is 796.3340681 (Soccer - Management). As the other elements (Clubs, Scotland) are absent from the notation, it becomes very difficult to express them in the indexing. Thus, anyone using a library catalogue that purports to be based on chain procedure should not expect too much from it library subject indexes of this kind provide a rough and ready guide to the whereabouts of the various topics; for serious searching they are a starting point and nothing more.

Figure 6.7 Chain indexing applied to a DDC classified catalogue

Assigning Subject Headings

As subject headings are pre-coordinated, and can often be used as they stand, it is easy to think that assigning them is simply a matter of picking from a list. In reality there are a number of issues to be considered. These include:

Policy issues:

Are subject headings to be assigned:

only to complete works?

to partial contents, where a substantial part of a work deals with a distinct topic?

to individual chapters, articles, etc.?

to parts of a work, as analytical entries, where a work consists of a small number of discrete items?

What is the maximum number of subject headings that can be assigned to a work?

Are there any categories of work to which no subject headings are to be assigned? (Possible examples include fiction and general periodicals.)

If a specific heading is not available, is there a mechanism for creating a new heading?

If keyword access is available on the OPAC, do the subject headings complement the keywords available elsewhere in the record, or are they searchable independently of them?

In working situations, headings and their references are recorded in a Subject Authority File (see Chapter 14).

Specific entry: use the most specific heading that will accommodate the subject content of the work. If there is no specific heading, and a new heading cannot be created, use the nearest broader heading.

Multiple headings: consider whether more than one subject heading is needed to cover the major aspects of the subject content Occasionally, depending on policy, additional subject headings may be assigned to express subordinate themes within the work.

Multi-topical works: if a work deals separately with two or three distinct topics, assign separate subject headings to each topic, provided that the topics do not together constitute a more general topic (e.g., a work dealing with inorganic and organic chemistry is assigned the single heading Chemistry).

Follow any scope notes governing correct usage.

Apply subdivisions judiciously, paying attention to LCSH’s often subtle rules governing their application and sequencing (where more than one subdivision applies). Again, check any scope notes, as distinctions between subdivisions (e.g., between Social conditions and Social life and customs) can be fine.

Summary

Subject headings have had a topsy-turvy history. Library of Congress Subject Headings in particular was for many years a target for abuse (and indeed offered some very easy targets). Ultimately it was saved by a combination of factors: the sheer weight of the resources behind it; apprehensions about the intellectual effort required to apply its strongest contender PRECIS; some much needed updating; and above all the change to OPACs with their keyword facility. In recent years the use of subject headings has been extended: both territorially (through the UKMARC record format) and in the range of documents indexed, as works of the imagination are now given subject headings, and new systems of headings have been developed for fiction.

Library of Congress Subject Headings and other subject heading systems are limited by the inability of pre-coordinated systems to express anything more than a broad summarization. While they are unlikely to offer more than a general indication of subject, their sturdiness and familiarity will ensure their survival even in an age of machine searching.

References and Further Reading

Bates, M. J. (1989) Rethinking subject cataloging in the online environment Library Resources and Technical Services, 33 (4), October, 400–412.

Calderon, F. (1990) Library of Congress Subject Headings: vested interest versus the real needs of the information society. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 11 (2), 85–94.

Chan, L. M. (1990) Subject analysis tools online: the challenge ahead. Information Technology and Libraries, 9 (3), September, 258–262.

Chan, L. M. (1995) Library of Congress Subject Headings: Principles and Practice, 3rd edn. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Chan, L. M., Richmond, P. A. and Svenonius, E. (eds). (1985) Theory of Subject Analysis: A Sourcebook. Littleton, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Coates, E. J. (1960) Subject Catalogues: Headings and Structure. London: Library Association.

Cutter, C. A. (1904) Rules for a Dictionary Catalog, 4th edn. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (and later reprints).

Drabenstott, K. M. and Vizine-Goetz, D. (1994) Using Subject Headings for Online Retrieval: Theory, Practice, and Potential. San Diego, CA Academic Press.

Dykstra, M. (1987) PRECIS: A Primer. London: Scarecrow.

Franz, L. (1994) End-user understanding of subdivided subject headings. Library Resources and Technical Services, 38 (3), 213–226.

Kaiser, J. (1911) Systematic Indexing. London: Pitman.

Langridge, D. W. (1989) Subject Analysis: Principles and Procedures. London: Bowker-Saur.

Library of Congress. Cataloging Policy and Support Office. (1966-) Subject Cataloging Manual: Subject Headings. Washington, DC: Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress.

Miksa, E. (1983) The Subject in the Dictionary Catalog from Cutter to the Present. Chicago: American Library Association.

Rolland-Thomas, P. (1993) Thesaural codes: an appraisal of their use in the library of Congress Subject Headings. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 16 (2), 71–91.

Sear’s list of Subject Headings (1997) 16th edn. New York: H. W Wilson.

Shubert, S. B. (1992) Critical views of LCSH - ten years later: a bibliographic essay. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 15 (2), 37–91.

Studwell, W. E. (1991) Of eggs and baskets: getting more access out of LC subject headings in an online environment. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 13 (3/4), 91–96.