7

Classification and systematic order

Introduction

This chapter brings together, and builds on, strands from the preceding two chapters. In it you will learn:

the place of classification in the scheme of controlled languages

the differences between natural and bibliographic classifications

the functions of bibliographic classification

the component parts of a bibliographic classification scheme: schedules, notation, index

the differences between the enumerative and faceted approaches to bibliographic classification

some practical guidelines for classifying documents.

Categories, Hierarchies and Systematic Arrangement

The formation of categories is one of the most fundamental of human learning activities. Many of us have observed small children in their attempts to categorize the everyday world, and can supply instances - a typical one being the two-year-old who classified birds as pigeons if they were flying and ducks if they were walking or swimming.

In Chapter 6 we learnt how to categorize pairs of terms in three basic ways: where term A is considered equivalent to term B; where A and B are in an hierarchical relationship; and where there is such a close association between A and B that the one forms part of the definition of the other. The skills we acquire in recognizing these relationships are essentially classificatory skills. We use these skills, often unconsciously, in a number of ways when accessing information. Some examples are:

Many menu-based user interfaces are hierarchically organized. We start with a broad area, and narrow it down in hierarchical steps to find the required information.

In traditional alphabetical indexes, if we wish to expand a search to a term that is hierarchically broader, the reference structure usually gives no help: we have to think of the broader term ourselves.

Conversely, in machine searching, if we wish to search on terms that are hierarchically narrower, we may be able to make use of an EXPLODE function, but more usually have to enter the narrower terms individually and OR them together.

Systematic Arrangement

Humankind’s attempts to classify the world are as old as knowledge itself - the biblical story of the Creation is an exercise in classification. Much of the human learning process is through classification - Bernard Palmer once gave a series of lectures on classification and published them (they are still worth reading) under the title Itself an Education. It is by classifying the objects and activities of the everyday world that children develop their world-knowledge, and this process is constantly being added to and fine-tuned throughout the life cycle. Most of us have seen the attempts of very young children to categorize the world. The 18-month-old who looked at the television screen showing King Kong tearing down skyscrapers and said ‘Doggy’ was merely trying to fit the unknown into his personal classification schema. The two-year-old who categorized all birds as pigeons if they were flying and ducks if they were walking or swimming had a slightly more sophisticated schema. As we learn, we extend and refine our personal classifications of the world around us.

Classifications of the objects of the everyday world are often known as taxonomies. Their archetype is Linnaeus’ systematic ordering of the world of botany. Such classifications work by grouping things together on the basis of their similarities and dissimilarities. Thus onions, leeks, shallots, chives and garlic are grouped together under the family name of Alliaceae.

The systematic arrangement of knowledge, or of the documents in a collection or index, has two important functions:

It gives us an overview of the subject field covered.

It makes it possible for information on a subject to be retrieved without having to search the whole file.

Most contents pages of books are effectively classifications of their contents. Encylopaedia Britannica has a classification of the whole of knowledge to introduce readers to its scope and organization. Other classifications are not hard to find. Governments maintain official classifications of occupations and industries; educationalists have classifications of schools and of exceptional children; supermarkets group their wares on their shelves, and so on.

Information professionals use classified order in many ways. One common use is to arrange current bibliographies. Users who are interested in keeping up to date on developments in a particular subject field can turn straight to it, either by turning the pages of a printed bibliography or by keying in its class code in a machine-retrieval system. Another use is in designing the knowledge bases for expert systems. Yet another is to give structure to data archives and knowledge repositories held by business and other organizations, so packages of relevant knowledge can be directed to users. An application that is increasingly important today is the design of menus for interactive searching. However, the longest established use of classified order is for the arrangement of the stock of libraries. A number of classification schemes have been devised for this purpose. Chief among them are the DDC, its offshoot the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC) and the LCC.

Library classifications have much in common with the taxonomic groupings of the everyday world, but there are important differences:

Taxonomic groupings of the everyday world are limited to generic relationships. Documents, as we have seen in Chapter 3, deal with combinations of topics, e.g. a report on the prevention of diseases in onions.

The classification of documents is governed by literary warrant: the actual or probable existence of documents that are about the topic for which a class has been defined. This principle has not always been recognized: DDC used many years ago to provide a specific class for library hat-stands (under the broader class Public conveniences), ignoring the extreme improbability of there ever being a literature on that topic.

Documents can only be arranged in a one-dimensional, linear order. This makes it possible for shelf arrangement to show only one kind of relationship at a time. Catalogues and indexes are necessary to supplement shelf order.

‘Library’ classification is to some extent a misnomer, as the same schemes are often used to arrange bibliographies (British National Bibliography, American Book Publishing Record among others are arranged by DDC) and latterly for the grouping of electronic files also: an example is the Web directory BUBL (Bulletin Board for Libraries), which also uses DDC. The term bibliographic classification is more accurate.

Bibliographic Classification

Functions of Classification

Traditionally, bibliographic classification has two functions:

Linking an item on the shelves with its catalogue entry. An item’s classmark forms part of its shelf mark (also known as call number and book number), which enables items located within a library catalogue to be retrieved from the shelves.

Direct retrieval by browsing. If we know where a subject is classed, we can locate it without having to search the whole collection; and can moreover expect to find related subjects nearby. However, because of the limitations of linear order, not all like subjects can be collocated. It is the function of a classification to group together the topics that the users of the collection are most likely to want grouped together (library shelves and, increasingly, virtual collections also).

These two functions taken together are sometimes referred to as marking and parking. The qualities that a bibliographic classification requires in order to achieve these ends are a helpful collocation and sequence, and a brief and memorable notation. Detail is not in itself a requirement, so long as there is enough of it to spare users from having to scan long sequences of items carrying the same classmark. The detailed retrieval of items through the catalogue is achieved through a verbal indexing language. Classification and subject cataloguing are thus seen as distinct and separate.

Some would give classification a third function. Many librarians of special collections have developed detailed, specialized classifications - detailed enough for the topics in the classification, translated back into words, to be used as the basis for compiling the subject catalogue. Traditional enumerative classifications were by and large incapable of supporting this function; but UDC, supplemented by Ranganathan’s development of faceted classification in the 1930s, greatly extended the ability of classification to support pre-coordination, to the extent that it became possible for even highly specialized research libraries to base subject indexes on the classification.

The techniques used to construct faceted classifications and their accompanying subject indexes were essentially the techniques of thesaurus construction with systematic order and preordination thrown in. By this argument, thesauri, subject headings and classifications are all manifestations of the same ‘deep’ index language structure (which, broadly, is the position taken by this book). These new theories and practices were seized on with eagerness, mainly by the British library community, to the extent that classification was held to be the key to all information retrieval; and a lot of energy was expended in the pursuit of the will-o’-the-wisp of a truly universal classification scheme that could be drawn on for use in any kind of information retrieval situation. In recent years there has been some reconciliation of these opposing perspectives on classification and information retrieval generally.

General and Special Classification Schemes

A classification may be general or special. A general classification covers all subjects. A special classification concentrates on a narrower range of topics, typically the goods manufactured or services provided by the organization for which it has been developed. Some general classifications, notably UDC and BC2, have been developed in sufficient depth to enable them to be adapted to special collections.

Component Parts of a Classification Scheme

Why classification scheme? A classification is simply a systematically arranged list. To be of practical bibliographic use a classification needs additional features, and these are what make it into a scheme. A classification scheme has three components:

the schedules, in which subjects are listed systematically showing their relationships. This grouping is not self-evident, and therefore it requires:

a notation, a code using numbers and/or letters, that have a readily understood order which signals the arrangement of the schedules, and

an alphabetical index to locate the terms within the classification.

It is often stated that a classification requires a fourth component: an organization to develop it and maintain its currency. This is true, but such a mechanism is not unique to classification, but is a feature of all controlled language systems.

Schedules

Classification schedules comprise the following elements:

the division of classes by a single characteristic at a time

main classes

facets, generated by facet analysis (as described in Chapter 6)

subfacets (arrays), formed by the subdivision of the facets by a single characteristic at a time

notation, a numeric, alphabetical or alphanumeric code to fix the position of each topic within the the schedules

alphabetical index, for accessing the schedules.

These will now be described in turn.

Division of Classes

Division of classes must be by one principle (characteristic) of division at a time. That is, all the subclasses have the same attribute. For example, garments can first be divided according to function (e.g., overcoats, dresses, underwear), and then within these functional groups, or classes, there will be further principles of division, such as size or material.

Failure to observe this principle (see Figure 7.1) reduces the predictability of the system and can lead to cross-classification, which could be problematic if you know of a tame stray dog or an embalmed sucking pig. More plausibly perhaps, DDC’s Architecture class (720) has subdivisions 722-724 for schools and styles, and 725-728 for types of structure. Ancient Egyptian architecture is at 722.2, and Temples and shrines at 726.1. Where to class a book on ancient Egyptian temples? The schedules have a clear instruction to use the latter number, and provide we know that types of structure take precedence over schools and styles, all is well.

There are two approaches to the division of classes: enumerative, and analytico-synthetic or faceted. Historically, bibliographic classifications have followed Lin-naean principles. Linnaeus divided the plant kingdom into Orders: flowering and non-flowering plants; and then proceeded by successive subdivision to enumerate the various genera and species of plants in their classes and subclasses. Such a top-down, deductive procedure applied to documents results in an enumerative classification. Both LCC and DDC are essentially enumerative classifications. This method of compiling a classification brings with it a number of problems:

Figure 7.1 Principles of division

Figure 7.2 Enumerative classification 1

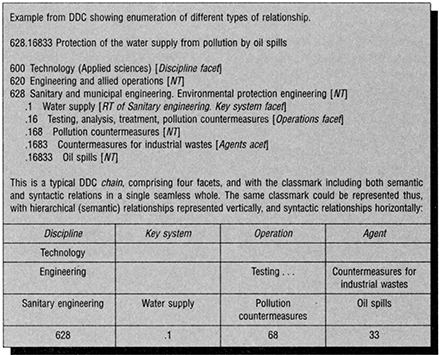

Successive subdivision of classes can only properly cover one kind of relationship - the hierarchical. Other semantic relationships, and all syntactic relationships, have to be assimilated as best they can. This in practice means that relationships of different types are listed in the schedules in a way that makes them look hierarchical when they are not. Figure 7. 2 shows how a single DDC class can include associative as well as hierarchical relationships, together with a range of syntactic relationships.

Successive subdivision of classes carries the temptation to continue subdividing for the sake of it, ignoring literary warrant, as with the library hat-stands.

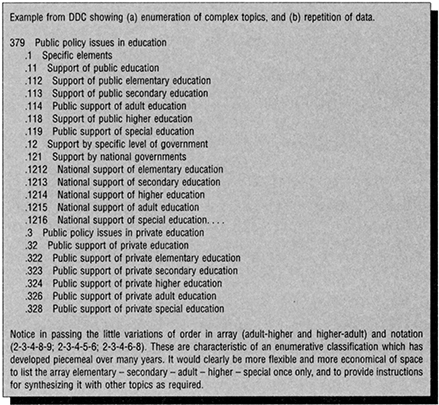

Another problem with enumerative classification is that of repetition. Subordinate topics have to be enumerated every time, which bulks out the schedules (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Enumerative classification 2

Enumerative classifications behave in a very similar way to enumerative subject headings lists, in that they may permit only a limited amount of preordination. Just as a work on the architecture of wooden church buildings would carry the LCSH headings Church architecture and Wooden buildings, so the best that an enumerative classification like DDC can offer is 721.0448 Architectural structure - Specific materials - Wood, and 726.5 Buildings associated with Christianity (class here-church buildings), with no provision for combining the two. However, whereas an item can carry more than one subject heading, we are forced to make a choice between two non-specific classmarks. There is a very real danger of cross-classification, the classing of works on the same subject at two different places. (DDC is good at anticipating this kind of problem: at 721 there is an instruction to ‘class architectural structure of specific types of structures in 725-728’.)

Figure 7.4 Enumerative and faceted classifications compared

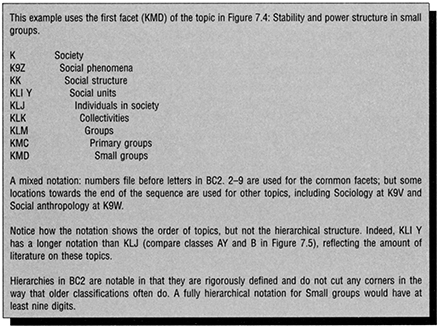

Faceted classifications are constructed in an inductive, bottom-up manner, as was described in Chapter 6. Figure 7.4 shows the principal features of a faceted classification:

Compound topics are formed by synthesis.

The classification is infinitely hospitable to new compounds. All facets can be expressed. Suppose, for example, someone made a study of resistance to change in the power structure of small groups. No problem: simply alter the final facet to KCT X Resistance to change, giving KMD GMR CDC.

Summary of Enumerative and Faceted Classification

Enumerative classification

There is a temptation to dismiss enumerative classification as antiquated and inflexible. While there is some truth in this, it need not be dismissed out of hand. Dewey Decimal Classification and LCC go back a long way and have solid institutional support, and the story of DDC in particular over the past generation has been one of careful and sympathetic improvement, and the piecemeal incorporation of faceted features. These vary in extent: 780 Music is fully faceted, but 150 Psychology has very few such features.

Dewey Decimal Classification and LCC are sophisticated, well developed and widely used schemes.

Perhaps the strongest inherent advantage of enumerative classification is that it is constructed and displayed in a way that can be intuitively understood. If we take a topic like ‘Stability and power structure in small groups’ we think of it like that: as a phrase, not as three facets to be stuck together. And if we cannot find the precise topic, we look for the nearest match, in the spirit of compromise that is part and parcel of everyday life. In spite of its many faceted features, and sometimes labyrinthine instructions, DDC can be picked up and understood in its main features with little preliminary training, and LCC is even more thoroughly enumerative than DDC.

Enumerative classification is incapable of the depth of pre-coordination (hospitality in chain) of faceted classification. This is not often a problem provided a generally helpful sequence of topics is maintained, and the system is not used in the compilation of verbal subject indexes.

It is true that it is unsystematic in application. Synthesis is unevenly developed, and methods vary from class to class.

Enumerative schemes are more difficult to revise, because enumerated compounds have to be relocated.

Schedules tend to be bulky, because the enumeration of compound topics leads to much repetition of data. This, however, is becoming less of a practical (i.e., weight!) problem now that electronic access to schedules is available.

Faceted classification

Faceted classification has largely been developed since the 1950s.

Schemes can be daunting at first appearance, as the construction of compound subjects requires both knowledge of the methods of synthesis used and looking up two or more places in the schedules.

It offers hospitality in chain to any degree, subject only to the overall limitations of pre-coordination.

Schedules are compact, as only simple topics are listed, with little repetition of data.

Application is systematic and predictable. With familiarity, the classifier can work with speed and confidence.

Schemes can be more easily kept up to date.

Faceted classification has had an incalculable influence on the development of controlled languages over the past half century, but the schemes themselves are largely confined to a few specialist applications. DDC and LCC have an iron grip on general libraries, and BC2 has been developed too late and with insufficient resources to make a significant impact. The rapid growth of mechanized post-coordinate retrieval methods has meant that classification can get by without the level of detail that is required to support a subject index.

Main Classes

General classifications, whether enumerative or faceted, must have an initial system of broad classes, called the main classes or primary facet. All current classifications base their main classes on disciplines. Disciplines are ways of looking at the world. The narrowest definition of disciplines postulates a small number - perhaps six or seven - of fundamental disciplines, and contrasts them with phenomena, the objects of the world, any of which can be studied from more than one disciplinary viewpoint. Many of the traditional disciplines of professional and academic life are, according to this perspective, subdisciplines: a fundamental discipline applied to a particular group of phenomena. So biology is science applied to living organisms, social science is science applied to human groups, and so on. Bliss Bibliographic Classification, second edition, is constructed in this way (see Figure 7.5).

The use of disciplines raises a number of questions and problems:

There is a large body of literature, often but by no means exclusively written for children, the focus of which is a phenomenon treated from a range of disciplinary viewpoints: Water, Colour, Life underground, and so on. (BC2 reserves class 3 for such topics.)

Figure 7.5 Order of main classes in BC2

There needs to be provision for topics that are too general in scope to fall within the disciplinary structure. Traditionally, such topics have been placed in a main class labelled Generalia. These may include:

- the vehicles for communicating information: books, journals and so on

- documents with no subject limitation, which may be classed by their format or arrangement: encyclopaedias, general newspapers, and the like

- the tools of knowledge: systems, computers

- the disciplines associated with any of these: publishing, information science, librarianship, bibliography.

Not all disciplines are clear-cut. Geography for example is a loose aggregate of topics.

Disciplines are by no means static, but are constantly evolving and being added to, often by the fusion of distinct fields of study, as with biochemistry or psycholinguistics - there was a book published some years ago with the title Biological and Social Factors in Psycholinguistics. Where such topics have to be accommodated within an existing disciplinary framework, anomalies and second thoughts can result, as with DDC’s recent relocation of the sociology of education from 370.19 (within Education) to 306.43 (aspects of the sociology of culture).

The number and order of main classes are determined by:

- philosophical and scientific considerations. Bliss studied for 40 years to find a ‘scientific and educational consensus’ on which to base his classification. Francis Bacon and Hegel are both said to have influenced Dewey in his choice of main classes.

- the practicalities of the notation. In theory, anyone constructing a classification should determine the number and order of the classes first, and then apply a notation; but there is no denying that Melvil Dewey thought of the notation first and adapted the schedules to it.

- other considerations, from the pragmatic to the ideological. For example, the Library of Congress’s primary function is to serve Congress, and a basic function of government is national defence. The LCC accordingly has a main class for military science. Or take Colon Classification (CC): to its deviser Ranganathan, mysticism was the pinnacle of human experience, so he created a main class for it, gave it a suitable notational symbol - the Greek letter delta (A) - and located it at the very centre of his classification.

Facets

A vocabulary of terms organized into broad facets is the defining structural feature of a faceted classification. The terms are derived from the literature, using the technique of facet analysis outlined in Chapter 5. An important difference between the terms of a classification schedule and a verbal system is that the terms of a classification represent the concepts defining each class, whereas the terms in a verbal system are labels for retrieval. In many cases these are identical. Where they are not so, classes can be defined by means of headings such as Secondary forms of energy, Persons by miscellaneous social characteristics, or Postage stamps commemorating persons and events, which would be unacceptable (except as node labels) in a verbal system. As they are collected, many of the terms will tend to organize themselves into groups. These are the broad facets of the classification. A facet is the total subset of classes produced when a class is subdivided by a single broad principle or characteristic.

Subfacets or Arrays

Once the broad facets have been determined, each must be examined to see if it can be further subdivided by a more specific principle into subfacets, or arrays. The order of classes within an array can often be determined intuitively, the guiding principles being that (a) any hierarchies must be indicated, and (b) alphabetical order is used only as a last resort. More specifically, the following arrangements have been found useful:

chronological, e.g. for history and literature; also for operations carried out sequentially, e.g., the sequence of agricultural operations from ploughing to harvesting

evolutionary, e.g., the stages in the life cycle

increasing size or complexity, e.g., for musical ensembles

spatial, with the proviso that classification is one-dimensional, making it impossible to maintain full geographic contiguity. Thus, in DDC’s Table 2 (Geographic areas), the first area enumerated under -4 Europe is 41 British Isles, from where the table crosses the North Sea to Germany and tours the central European states as far as Hungary (439); after which it skips to France (44), Italy (45), Spain and Portugal (46); then an even greater leap to Russia and Scandinavia. At is perhaps comforting to find that 611 Human anatomy is better ordered.)

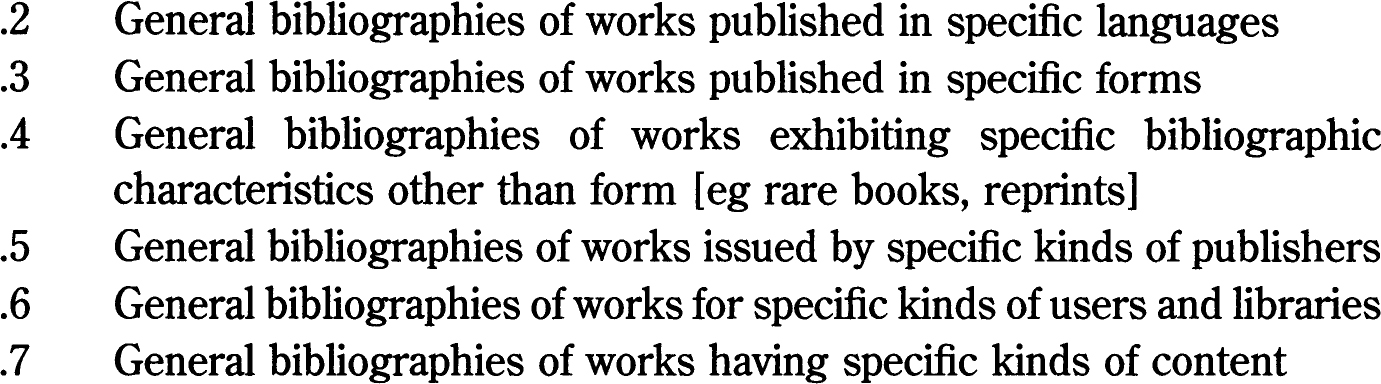

Enumerative systems such as DDC also recognize subfacets. For example, Oil Bibliographies has these divisions:

However, whereas a faceted classification would be able to express as many of these characteristics as required (e.g., serial publications from underground presses, or rare books in microform), with DDC it is only possible to express one characteristic.

Unless a classification is intended for in-house use only, it is helpful to allow alternative locations where user feedback suggests that other collocations might be preferred. For example, in DDC much the greatest part of class 200 is given to the Christian religion. No fewer than five different options are offered to users who wish to give preferred treatment to a specific religion.

Citation Order

The principles are precisely the same as for pre-coordinate systems generally (see Chapter 6) except that in general classifications discipline forms the primary facet

Alternative citation orders are sometimes offered. An example from DDC is subject bibliographies (016), where the preferred citation order is Bibliographies - Subject, as 016.61 for a bibliography of medicine. The alternative treatment scatters subject bibliographies by topic instead of keeping them all together, as 610.16.

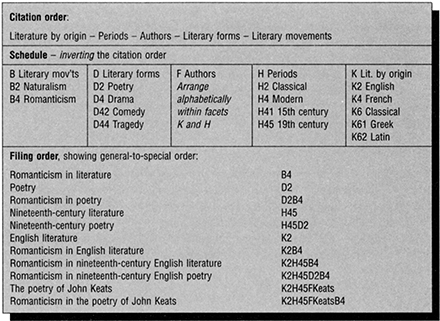

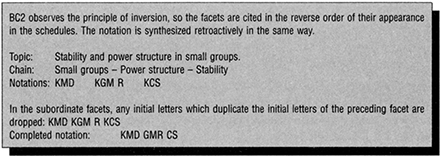

Filing Order

Filing order is the actual sequence of books on shelves, citations in bibliographies, etc. There is an apparent paradox here. Schedules are arranged from general to specific, which means that the least significant facet is listed first and the most significant last. In other words, filing order is the reverse of the citation order. This is known as the principle of inversion, and maintains the principle of filing general topics before special in syntactic as well as in semantic relationships (Figure 7.6). In DDC the principle is seldom specifically acknowledged, but often followed in practice, in ‘class elsewhere’ and ‘preference’ instructions. For example, when classifying the book on ancient Egyptian temples referred to earlier, there is an instruction at 722-724 to ‘class specific types of structures regardless of school or style in 725-728’ - that is, at the later class. For the bibliographies at Oil, there is the preference instruction: ‘class a subject with aspects in two or more subdivisions of 011.1-011.7 in the number coming last, e.g. Russian-language newspapers on microfilm 011.36 (not 011.29171 or 011.35)’.

Figure 7.6 Citation order and filing order

Other Components

Notation

Notation is a code applied to topics in order to fix their arrangement. Thus notation or code may be used in organizing books on shelves, files in a filing cabinet, entries in a catalogue or bibliography, or electronically held resources or their representations. The term ‘notation’ is generally used of document arrangement for shelf retrieval and for manually searched files. The more general term ‘code’ is used in machine retrieval.

Notation fixes a pre-existing arrangement: that is, it is applied to the schedules of a classification system after the subjects to be included, and their order, have been settled. It is necessary because systematic order is not self-evident.

After fixing the order of classes, the next important function of notation is hospitality: the ability to accommodate new subjects. For manual searching, a notation should be easy to use. Finally, there is the question of expressiveness: it is open for a notation to express the hierarchical structure of the classification, and also to express the facet structure of compound topics. These considerations will now be discussed in turn, together with a brief consideration of shelf notation.

Showing the order of classes

The purpose of notation is to give each class an address that fixes its order within the classification. The ordinal values of Arabic numbers and roman letters are widely understood and form the basis of all notations. Where more than one kind of symbol is used - a mixed notation - filing precedents may have to be set, and here the ASCII sequence of numbers - upper case - lower case is used. Where non-alphanumeric characters are used, they are assigned arbitrary ordinal values.

Hospitality

Notation must be hospitable to the insertion of new subjects. There are two methods by which this can be achieved:

Unassigned notation within an array. If the new topic is coordinate, all is well if a suitable gap has been provided. DDC20 classed Roller skating at 796.21, with 796.22 unused; DDC21 has appropriated 796.22 for Skateboarding.

Subdivision of the notation. If the notation is hierarchical and the new topic is by nature subordinate, it can be slotted in naturally. DDC20 used 004.67 for wide area networks (WANs), and DDC21 has inserted a class for the Internet at 004.678. However, if the array of subordinate topics has a larger number of classes than the notational base can accommodate, then the hierarchical nature of the notation is inevitably compromised. Greece recently set up 12 new regional government areas, for which provision has been made in DDC21’s Table 2, where some of the regions have four digits and others five, as the notational base is too short to allow them all notations of the same length.

Any more extensive revision in an established scheme is likely to involve the reuse of existing numbers with new meanings. The recent revision of DDC’s Life sciences class has tried to reduce the burden on individual libraries by leaving unassigned class 574, which was very heavily used in previous editions.

Ease of use

A notation should be easy for users to remember, copy, and shelve books by. To a large extent this is a function of brevity, the shorter the notation the easier it is to remember. Length of notation is determined by:

The notational base. There are over twice as many letters as numbers, so a lettered notation will be shorter than one that uses numbers alone.

The allocation of notation to the literature. This particularly affects established classification schemes, whose main classes may have been established for a century or more, and where the original allocation becomes less balanced with time and the emergence of new subdivisions. Growth subjects like electronic engineering tend to have long notations (621.38 in DDC), which gives all topics within that class even longer notations: 621.389332 is the number for Hi-fi systems. Conversely, some subjects have little or no growth. The classic instance is Logic (160 in DDC). It is a salutary exercise to go round any general library making a note of the length of shelving taken up by each main class.

Provision for synthesis: the more facets, the longer the notation. In DDC this can lead to some very long notations, especially in classes such as 338 Production, where the synthesis of Topic + Industry + Place leads to prodigious notations: a history of the Merseyside ship repair industry is classed at 338.476238200288094275. Where synthesis is systematic, as in faceted classifications, the notation for a facet will be consistent. In BC2 for example 28 introduces Place, so that 28S will always denote Japan. In DDC synthesis is anything but systematic: Africa is often denoted by -096, but 344.096 denotes Laws relating to religion; a class mark ending in -03 often denotes a dictionary or encyclopaedia, but 697.03 denotes central heating.

Mnemonics, where the same notational symbol is consistently used to denote the same topic, is properly an aspect of synthesis. Occasionally a classification having a lettered notation may be able to use literal mnemonics based on the initial letter of a subject. BC2 has AL Logic, AM Mathematics, C Chemistry, among others. There is however a temptation on the part of the designer of classifications to allow literal mnemonics to distort the order of the schedules; and they can raise false expectations among users - for example that B should denote Biology. (In BC2 B is Physics, and Biology is E.) At worst, it can lead to the use of alphabetical order as a lazy substitute for classification.

Chunking: long notations are more memorable if broken up into shorter groups in the manner of telephone numbers. Many classifications (DDC, UDC, BC2) use groups of three symbols separated by spaces or points.

Expressiveness

The notation may express the hierarchy of classes, and if it is intended for machine manipulation, this is a requirement, as with the EXPLODE function with MeSH tree structures. With manual systems, anyone familiar with DDC tends to expect this: there is an intuitive satisfaction in observing that, say, 636 denotes animal husbandry, 636.1 horses, and 636.12 racehorses. However, maintaining hierarchical expressiveness has certain problems:

It can lead to excessively long notations.

It is impossible to maintain if he number of terms in an array exceeds the notational base (as with the regions of Greece mentioned above).

Human perspectives on hierarchical structures can change over time. Relationships between subjects change as knowledge develops.

Figure 7.7 shows a notation that is deliberately non-hierarchical.

The notation may also express the facet structure of classes. In a faceted classification, there is often an expectation that this will be achieved. Even DDC makes some use of facet indicators, both generally throughout the scheme, for example where 09 often (but by no means invariably) introduces place or time, and in individual classes, notably 780 Music, where both 0 and 1 are used only as facet indicators. A few classifications, notably UDC and CC, use non-alphanumeric symbols to introduce particular facets. Universal Decimal Classification, for example, encloses places between parentheses and uses the colon to introduce a whole range of relationships. This complicates filing, as it is not self-evident whether, say, 63:31 Agricultural statistics will file before or after 63(31) Agriculture in ancient China. Another drawback is that facet indicators make the notation longer. A simple way to avoid both problems is to use a lettered notation, the initial letter of each class being in capitals and the rest in smalls, e.g. TjgLmEs for a (hypothetical) notation containing three facets. A variation of this technique is shown in Figure 7.8. Douglas Foskett (Foskett and Foskett, 1974) used a pronounceable notation in his London Education Classification, with some wickedly memorable features, e.g. the notation for Students was Sad, and for Sex education, Pil.

Figure 7.7 Retroactive notation in BC2

Figure 7.8 Non-hierarchical notation in BC2

Shelf notation

The notation inscribed on the back of books may usefully be shorter than that used in catalogues and other indexes. Dewey Decimal Classification notation supplied by central bibliographic agencies is often segmented: that is, one or two points are shown at which the notation could be cut off. So the 21-digit class appearing above could be shortened to 338.4762382 or even 338.4 (the maximum allowed in the Abridged DDC).

The notation forms the basis of an item’s call number or shelfmark, the actual symbol on the spine of the item which determines its place on the shelves and which the catalogue uses to locate it. This has three elements:

a symbol denoting any special shelving sequence, e.g. oversize items (usually omitted for items within the main sequence)

the classmark proper (full length or shortened)

a device to denote the item’s position within that class. This may be a Cutter number - a letter Mowed by one or more numbers as a coded representation of the author’s name - or some other (usually simpler) device.

Cutter numbers are used by LC to arrange books alphabetically within a class number. They consist of the initial letter of the main entry heading Mowed by one or two numbers that represent the second or subsequent letter of the name. The precise distribution of the numbers depends on the initial letter. For most names beginning with a consonant the second letter:

a e i o r u y is represented by the number: 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

So the name Davidson might be represented by .D3, Deakin by .D4, and so on. The numbers may be expanded decimally, using the third letter of the name, so Dean might be .D42. Further expansion is applied as required. The system is collection-specific: two libraries applying Cutter numbers independently would be likely to assign different numbers to the same work. Hence the tendency to rely on numbers supplied by LC.

Cutter-Sanborn Author Tables are a modification, using three digits. For large collections, Cutter numbers provide a better collocation than systems based on the first three letters of the heading, or on the initial letter Mowed by a running accession number.

Alphabetical Index

The index to the classification schedules has two purposes:

to locate topics within the classification

to bring together related aspects of a subject which appear in more than one place in the schedules. (Indexes to classification schemes are sometimes known as relative indexes.)

Faceted classifications need only index the simple concepts appearing in the schedules. Related aspects are uncommon, but do occur (essentially they reflect polyhierarchies): for example, the index to class K Society of BC2 gives two locations for Ethnomethodology. Enumerative classifications must show enumerated compound subjects: examples from DDC were given in Figures 7.2 and 7.3. Additionally, DDC’s index also includes a selection of synthesized compounds: Pines, Elms and Eucalyptus for example have subheadings for Ornamental arboriculture, whereas Apples, Firs and Yews do not.

Revision

Bibliographic classifications are inherently out of date. In part this is due to the tendency of all controlled language systems to lag behind the times. Additionally with classification:

Classifications are necessarily closed rather than open systems. The ordering of a new topic is not automatic, as it is with verbal systems: only a controlling organization can determine the correct placing of a new topic within the schedules.

Any revision of the order of topics involves the physical removal of books from shelves, the altering of their shelf numbers, and their replacement - a far more labour-intensive operation than the altering of surrogate records.

So classification schemes tend to be revised on the principle of doing only as much as the market will bear. The point is stressed here to explain how it is that, even though modern faceted principles have been shown to be far superior to traditional enumerative classifications, the great majority of libraries use enumerative classifications. The Library of Congress Classification is almost entirely enumerative. The Dewey Decimal Classification is largely enumerative but with variable proportions of faceted features. The Universal Decimal Classification is a faceted system grafted on to an enumerative base. The Bliss Bibliographic Classification, second edition, is thoroughly faceted, but is incomplete and little used. Colon Classification, the original faceted classification, has few users outside its home country.

The Classification Process

These guidelines are based on DDC, but can be adapted to apply to any classification.

Analyse the Subject

Use title and subtitle, contents list and scan the author’s introduction for any paragraph describing the purpose of the book. Treat blurbs with caution -their primary objective is to sell the book.

In working situations you have outside sources: reviews, bibliographies (e.g., BNB, MARC records), subject experts, etc.

Make a mental note of the word or phrase which most precisely describes the subject: e.g. if it is on combine harvesters, note it as such, not as agricultural machinery.

Now Go to The Classification Schedules

The most reliable way to classify is to start at the most appropriate discipline in the summary tables and work downwards through the schedules.

What is The Discipline?

If the work appears to fall between two (or more) main classes, then:

class at the discipline which receives the greater emphasis

watch the schedules for instructions on classing interdisciplinary works

check the DDC index. If the first index entry has a classmark on the same line (and not after an indented subheading), that is probably the place to classify a topic covering more than one discipline (but check the schedules).

Which Aspect of the Subject First?

Check the schedules carefully for any table of precedence, class here note, or class elsewhere note. If necessary, check the broader containing headings for your subject (e.g., for 305.4 check 305, 302-307, and 300 - this is why it is always best to work downwards from the main class whenever you can.)

In any given subject, there is an expectation that the more important facets of a subject will be listed after the less important e.g., class Norman castles at 728.81 castles rather than at 723.4 Norman architecture.

Class at the passive system: i.e., at whatever is at the receiving end of any process or operation: e.g. a book on bovine medicine with cattle (636.2) rather than veterinary medicine (636.0896).

Follow any add instructions (e.g., to give 636.20896), but never try to combine two numbers from the schedules if there is no specific instruction to do so.

Anything normally falling within the scope of DDC’s standard subdivisions is classed last: i.e.,

- common subject aspects, e.g., historical aspects of X; also biography, management, philosophy, psychology, psychology, statistics, computer applications, etc.

- the subject in relation to a particular place

- the subject written for a class of users who would not normally be the target readership, e.g. Anatomy for nurses

- the way the subject is arranged or presented, e.g. dictionary, humorous treatment.

More Than One Subject

(A + B, where A and B are independent themes treated together in a work).

If one is clearly subordinate, ignore it (e.g. Chess and draughts).

If two equal subjects, class at the earlier one, unless there are contrary instructions.

If three or more within the same general subject field, class at the first more general class that will accommodate all of them.

If necessary, apply a combination of these rules.

Final Check

Always check a classmark upwards through every stage of its hierarchy. If doing so leads to a heading that is irrelevant or misleading, there is a strong possibility that you have selected an inappropriate number (another reason for starting with the main class and working downwards).

Summary

This chapter has led us from a discussion of classification as a fundamental human activity to an introduction to the theoretical features of a bibliographic classification and some practical hints on how to apply a classification scheme. Our account is necessarily brief, and should be supplemented by at least a selection of the fuller studies listed below.

In studying a construct as complex, abstract and highly organized as bibliographic classification, it is all too easy to lose sight of the principles among the plethora of detail. Much of this chapter has elaborated principles introduced in Chapter 5. It’may help to keep the following three principles from Chapter 5 firmly in mind:

Bibliographic classification is not something apart, but is in essence a means of organizing a controlled vocabulary. Turn back to the principles of language control section in Chapter 5, as a reminder of how the trio of basic semantic relationships - equivalence, hierarchical, associative - are displayed in classification schemes.

Facet analysis, introduced in Chapter 5, lies at the core of modern classification theory.

The systematic display that forms the most obvious feature of a bibliographic classification indicates its main purpose: to achieve the sequence of topics that is most helpful to the users of the system. The section ‘Displaying the thesaurus’ in Chapter 5 took us in steps from a simple alphabetical display to systematic displays which are at the threshold of bibliographic classification.

The present chapter has been at pains to take most of its examples from published general classification schemes, especially DDC. Much of modern classification theory was conceived as an antidote to the traditional classification schemes, and there was a tendency to treat classification theory and DDC and its companions as totally separate entities: theory on the one hand which bore little relationship to practice, and practice on the other which was entirely devoid of theory. This is not a helpful attitude, and it is particularly unjust to DDC, which has striven over the past generation to adapt itself to modern ideas. It is now time to look at the individual schemes in more detail.

References and Further Reading

Beghtol, C. (1998) Knowledge domains: multidisciplinary and bibliographic classification systems. Knowledge Organization, 25 (1/2), 1–12.

Buchanan, B. (1979) Theory of Library Classification. London: Bingley.

Cochrane, P. A. (1995) New roles for classification in libraries and information networks. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 21 (2), 3–4.

Foskett, A. C. (1996) The Subject Approach to Information, 5th edn. London: Clive Bingley; Hamden, CT: Linnet Books.

Foskett, D. J. and Foskett, J. (1974) The London Education Classification: A Thesaurus/Classification of British Educational Terms, 2nd edn. London: University of London Institute of Education Library.

Hunter, E. (1988) Classification Made Simple. Aldershot: Gower.

Hurt, C. D. (1997) Classification and subject analysis: Looking to the future at a distance. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 24 (12), 97–112.

Langridge, D. W. (1992) Classification: Its Kinds, Systems, Elements and Applications. London: Bowker-Saur.

Mcllwaine, I. C. (1997) Classification schemes: consultation with users and cooperation between editors. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 24 (1–2), 81–95.

Marcella, R. and Newton, R. (1994) A New Manual of Classification. Aldershot: Gower.

Mills, J. (1969) Bibliographic classification. In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, vol. 2, pp. 368–380. New York: Dekker.

Mills, J. and Broughton, V. (1977) Organizing information and the role of bibliographic classification; and, The structure of a bibliographic classification. Both in Bliss Bibliographic Classification, 2nd edn. Vol. titled Introduction and Auxiliary Schedules, pp. 29–34, 35–48. London: Butterworths.

Palmer, B. (1971) Itself an Education: Six Lectures on Classification. London: Library Association.