12

Manual information retrieval systems

Introduction

This chapter draws together a number of information retrieval topics, many of which are of particular interest in printed and card-based indexes. Although electronic indexes have taken on a central significance, there remain many applications in which it is necessary to arrange printed documents, or to create and use printed indexes. Most kinds of index today are computer-produced. They are nevertheless discussed here, as the mode of searching concerns us even more than the means of production. At the end of this chapter you will:

understand the principles associated with document arrangement for effective browsing and document location

know the points of similarity and contrast between manual and machine-searchable indexes

understand the components of printed catalogues and indexes

be aware of the main approaches to the creation of printed indexes

understand some techniques for the effective searching of printed indexes

be acquainted with the key principles of book indexing

appreciate the significance of filing sequences and some of the problems associated with establishing effective filing sequences.

Document Arrangement

General Principles

Documents in libraries or resource centres must be physically stored. With closed access collections, storage may be by factors that are not significant for retrieval, for example by size or by date added. Access is by means of indexes, and the information professional will act as an intermediary between the stock and the user. Open access environments are different. Documents must be arranged or physically stored in an order which requires a minimum of explanation, and which matches as far as possible the search patterns of users.

The open access principle helps both management and users. Self-service was commonly available in libraries for many years before it was taken up by the retail trade. Managerially it is clearly cheaper to allow users to carry their own books off the shelves than to have to request them from a librarian and have them fetched from a stack. The self-service principle also respects the privacy of the user. Users may not have clearly articulated their requirements in their own minds, and a library whose shelf arrangement and physical environment encourage browsing is one of the simple pleasures of civilization.

In some environments document arrangement may be the only retrieval device available to, or used by, users. Examples of such environments are bookshops, music shops, small public libraries and document filing systems. In larger document collections browsing the whole collection is not an option, but subsets of the collection may be examined by browsing. Various document characteristics that are rarely reflected in catalogues, such as the precise scope of the work and its level of difficulty, as well as its physical format, the quality of production and the design of the cover, can be identified. Hence, despite its relative lack of sophistication, document arrangement is an important and frequently used retrieval device.

Approaches to Document Arrangement

The arrangement in a collection is unlikely to follow one sequence for all types of material. As always, a balance must be struck between managerial priorities and user convenience. In this section, the various types of shelf arrangement that encourage browsing will be discussed, followed by the factors which may lead to sequences being modified or broken.

Detailed classified subject arrangement. Detailed, or ‘close’, classification is the commonest arrangement for the majority of open access stock in all but the smallest collections. Long sequences of books sharing the same classmark but having heterogeneous but related subjects are an irritation to purposeful browsing, and a detailed classified arrangement minimizes this.

This arrangement is subject to the problems of classified order generally, whereby complex relationships have to be accommodated within a one-dimensional linear order, so only one relationship can be shown, and other related material is inevitably separated. Occasionally libraries try to improve the collocation of DDC’s main classes by rearranging their physical sequence in what is known as broken order. Class 400 (Languages) may be located adjacent to 800 literature, for example.

Broad classified subject arrangement. The principal drawback of detailed classification specifically is that shelfmarks can become unmanageably long. Smaller libraries may opt for a less detailed version of a published classification - often DDC, which publishes an official abridged edition; there are abridged versions of UDC and BC1 also. This reduces the length of classmarks (though they may still have seven or more digits in the Abridged DDC). Where segmented DDC classmarks are available on MARC records, abridged DDC classmarks can be obtained by programme, by cutting off the classmark at the first segmentation point. Otherwise classifiers have either to classify from scratch or apply their own abridgement. The Dewey Decimal Classification for School Libraries offers even broader arrangements designed for secondary and (with even less detail) primary schools. As an example, 690 Building and related activities has just three divisions, and the recommen dation for primary schools is to class everything at 690.

Some public branch libraries have adopted ‘reader interest’ arrangement. This name is given to a whole group of single-facet classifications, mostly devised in-house. Reader interest arrangement is born out of exasperation: the exasperation of readers trying to find their way round DDC’s unhelpful collocations and overlong notations, and of readers’ advisory staff trying to explain to them that d-i-y is classed at 643.7, except that carpentry is at 694, but not woodworking which is 684, unless it’s marquetry and similar handicrafts, for which you will need 745.51. And so on. These arrangements are often intuitive and very broad, 30-40 classes sufficing for the whole collection, with simple, sometimes iconic, notations.

Verbal subject arrangement may be considered if a collection is small enough, and the range of topics restricted enough, for the whole collection to be comprehended together. This warning is offered because of the inevitable limitation of verbal subject arrangement. It is quite indifferent to relationships, and gives an arbitrary sequence. The distinction between a verbal arrangement and a very broad classified arrangement is a fine one: some reader interest arrangements do not attempt to show relationships between subjects, and might be better considered as verbal subject arrangements. This is the kind of arrangement commonly found in bookshops. It also has its uses for the arrangement of small, specialist collections, for example, files of community information material or of photographs in a local collection.

Title arrangement for direct retrieval is found mainly in the specialized context of periodicals, often within broad subject categories corresponding to the library’s physical organization.

Author arrangement is traditionally found in the fiction section of public libraries, though even here it is increasingly common to find genre fiction grouped or labelled separately. Within a classified sequence, items are commonly subarranged by author, and the shelfmark will indicate this.

Parallel sequences

Very few libraries arrange their classified stock in a single sequence. A variety of parallel sequences is almost universally found. Some situations that lead to sections of stock being shelved in a separate classified sequence are as follows:

Physical form. While improvements in packaging have made it possible to box up many videos, audio cassettes and other audiovisual materials in a way that makes them suitable for interfiling with books, many libraries prefer for security or other reasons to house such materials separately. This applies particularly if equipment - video cassette recorders (VCRs), PCs, fiche readers, slide viewers and the like - is needed to use such material within the library. Some items, such as graphic materials and portfolios, are simply too large or awkwardly shaped to be shelved with books.

Books themselves often have one or more separate sequences for oversize items. Pamphlets, reports and similar items that are too slim to have a spine may be placed in separate sequences.

Nature of use. Separate sequences may be established for items where special conditions are imposed on their use, for example short-loan collections in academic libraries. Lending and reference stock are commonly segregated, and there is often a separate quick reference sequence for yearbooks, directories and other materials that are designed for rapid consultation.

Readership level. Separate undergraduate collections may be found in academic libraries. School and public libraries often split the stock into categories reflecting the child’s level of reading and emotional development

Guiding

Library guiding is essentially the system/user interface as described in Chapter 4, but writ large, and static rather than interactive. The range of sequences that are likely to be found even in quite small libraries underlines the need for users to be given clear information about the whereabouts of every item of stock. Such guidance may take forms that are specific to individual environments, but may include:

group or individual instruction in the layout and use of the collection

within the catalogue, shelfmarks must clearly indicate the sequence within which an item is housed

users of the catalogue should have easy access to information guiding them to each sequence

clear and explicit guidance that is visible within the library

guidance as necessary on book presses and shelves.

Limitations of Document Arrangement

Document arrangement is a crude retrieval device that normally needs to be supported by other approaches. Specifically its limitations are that:

documents can be arranged in only one order, and grouped according to one characteristic

any given document can only be located in one place in any given sequence

the document arrangement adopted is often broken; parallel sequences are common, and additional complexity may be introduced by the need to accommodate large collections on several different floors of a library building.

only part of the library collection will normally be visible on shelves, or in filing cabinets. Documents that may be available through a library, but which will not be evident through browsing include: documents on loan, documents which might be obtained by interlibrary loan, and any collections that are maintained on closed access.

While document arrangement has some significant limitations for the retrieval of both documents and the information contained within those documents, it is important to remember that document arrangement is used widely in documents, archive collections and paper-based filing systems, and, overall has an important impact on information retrieval.

Manual and Computerized Catalogues and Indexes Compared

A conscious effort of imagination is often needed when changing from a manual to a machine method of searching or vice versa. This section discusses manual and machine techniques generally. It has to be borne in mind that the capabilities of mechanized searching vary enormously according to system and that some systems, particularly older OPACs, offer relatively few enhancements over manual searching.

Availability and Accessibility

There will continue to be some demand for printed indexes for manual searching for the foreseeable future, on account of their familiarity, instant availability, portability and freedom from mechanical or electrical failure. Manual indexes are normally purchased, singly or on subscription, by libraries and other information organizations, and made available freely to authorized users. Some printed indexes may be locally produced, for example, printed catalogues, and copies may be available for sale. Card indexes are usually assembled on site.

Microforms require readers, but they are subject to mechanical breakdown. These, and card indexes, are not portable. Other manual systems are always accessible and their use does not require machinery. Printed indexes are portable, and may be carried around and used with other materials: for example, printed abstracting and indexing services may be used alongside the journals that they index. This is not usually possible with mechanized formats. Computerized systems are also subject to downtime and networked systems can suffer from slow transfer rates or connection failure.

Manual indexes have a long life span and are usable for as long as needed. The contrast here is with WAN-based systems, where access time is limited by expense. In-house mechanized systems, such OPACs and CD-ROMs, are usable for as long as needed.

While the range and date span of machine searchable databases have improved dramatically over the past generation, some search services are still only available in manual formats. There are also many defunct manual indexes that are still of value, especially in the arts and the humanities, as well as the pre-computerized back files of machine-searchable databases in all subjects. Nor must it be forgotten that developing areas of the world may not have the resources - or even a reliable electricity supply - to support automated systems.

Currency

The currency of manual indexes of all types is usually inferior to that of machine systems, as time is taken up for physical production and for the distribution of published indexes. Even locally maintained card indexes often have a backlog of entries for filing, as the work involved is slow and tedious and at the same time requires great accuracy and a knowledge of complex filing procedures. The updating of machine systems is usually instant - though the release of updates of publicly available systems is done on a regular-interval basis. CD-ROMs share with manual systems the feature of requiring physical production and distribution.

Static and Dynamic Lists

One of the two most important points of contrast between manual and mechanized systems is that the former depend on static lists. A static list is any index that has a physical substrate - printed page, card, microform or the physical arrangement of library materials. The list is permanent, or nearly so, and is not altered by use. These lists are costly to compile and (where applicable) to distribute, and take up physical space. Access is by consulting relevant sections of the list A search is only able to retrieve what is on the list, so queries have to be tailored to what the list can offer.

With machine systems the physical ordering of records is hidden from the user. Interrogation of the system produces dynamic lists. These are the records that have been retrieved from the system in response to a specific query. Each list is tailored to its query. Depending on the sophistication of system and user, it may be possible to fine-tune a list in respect of record format and file arrangement.

Access Points

These considerations lead to the second most important point of contrast Because of the cost in space and time of producing and maintaining static lists, information organizations make them as simple as they can, by limiting both the amount of data in the individual record and the number of access points available. Access points in manual systems typically consist of: the first word of the title, the author and one or more subject access points - rarely exceeding four or five, and often fewer.

In machine systems the number of access points depends on the size of the record, the number of indexed fields and on whether a keyword facility is available. The number of access points is normally far higher than in machine systems.

Searching

Because of the limited number of subject access points in manual systems, each one may carry a heavy freight of information. This means that manual systems are often pre-coordinate systems, where a single access point may carry two or more elements of information, the subordinate elements being picked up by means of references. The searcher has to scan through static lists, therefore it is laborious to modify a manual search. However, because the exhaustivity of indexing is limited and pre-oordinate systems are commonly used, false coordinations are uncommon, and the precision of a search can be high.

Scanning and browsing can be easy or difficult, depending on layout and typography. Manual systems can be accessed with a minimum of preliminary training. Written instructions should be available, however, and training may be useful in situations where more complex search patterns are available - as for example in some scientific abstracting services. At best, the ‘browsability’ of manual indexes encourages serendipity. A combination of machine searches supplemented by manual indexes and citations is an effective and absorbing way to conduct a literature search and build up a personal bibliography.

Machine systems normally operate in post-coordinate mode, where it is easy to modify a search by adding or discarding search terms. While great strides have been made in improving the user-friendliness of user interfaces, there are still many situations where much training and practice are needed to exploit systems to the full. Scanning and browsing capabilities depend on the interface; in the case of the WWW they are seductively easy.

Search Output

Output from a manual search has to be memorized or copied: by manual copying in most cases, otherwise by photocopying or electronic scanning. All are laborious. However, the portability of most systems makes it easy to compare different sources. Output from machine systems can usually be printed or downloaded to file - though institutions may impose restrictions.

Printed Catalogues (Including Card and Microforms)

Any catalogue comprises a number of entries, each entry representing or acting as a surrogate for a document (see Chapter 3). There may be several entries per document, or just one. Each entry comprises three sections: the heading, the description and the location.

Headings determine the order of a catalogue sequence. The entries in an author catalogue will have authors’ names as headings, and the catalogue will be organized alphabetically according to the author’s name.

The common types of catalogue are:

Author catalogues, which contain entries with authors’ names as access point Authors may be persons or corporate bodies; the term ‘author’ is normally extended to include illustrators, performers, producers and others with intellectual or artistic responsibility for a work. A variant sometimes found is the name catalogue, which includes in addition personal names as subjects and, sometimes, corporate bodies.

Title catalogues, which contain entries with titles as access points.

Author/title catalogues contain a mixture of author entries and tides entries; since both are alphabetical these can be interfiled into one sequence.

Subject catalogues use subject terms as access points.

Alphabetical subject catalogues use verbal subject headings as headings.

Classified subject catalogues use notation from a classification scheme as a heading. As this order is not self-evident, classified catalogues require a subject index, an alphabetical list of subjects and their classmarks.

Normally a combination of these catalogue sequences will be used. There are two different approaches:

classified catalogue, which has the following sequences: an author/title catalogue or index (or separate author and title catalogues), a classified subject catalogue and a subject index to the classified subject catalogue

dictionary catalogue, which has only one sequence (like a dictionary) with author, title and alphabetical subject entries interfiled.

Printed Indexes

Two basic types of indexes are common: author indexes and subject indexes. A subject index has alphabetical terms or words as headings. Entries are arranged in alphabetical order according to the letters of the heading. An author index may be created; here entries are arranged alphabetically by authors’ names. The descriptive part of an entry in an index depends upon the information or document being indexed. Three important contexts in which printed indexes are encountered are:

Book indexes. A book index is an alphabetically arranged list of words or terms leading the reader to the numbers of pages on which specific topics are considered, or on which specific names appear. Many non-fiction books and directories include an index; this is often a subject index. The section below explores some of the principles of the creation of book indexes in greater detail.

Periodical indexes. A periodical index is an index to a specific periodical titles (for example Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society; or Managing Information) Usually indexes are generated at intervals to cover several issues; annual indexes are common. Periodicals may have subject, author and/or title indexes.

Indexing journals and the indexes to printed abstracting journals are alphabetical indexes to the literature of a subject area. Usually many of the entries relate to the periodical literature, but monographs, conference proceedings and reports may also be covered. The indexing journal normally comprises an alphabetical subject index, possibly also supported with an author index. The ‘description’ is the bibliographical citation that gives details of the document that is being indexed. Different approaches to generating these indexes in printed form are discussed in the next section.

Entries and References

In catalogues or indexes there are two possible approaches to the provision of multiple entries for one work. One of these is to use main and added entries. The main entry includes the complete catalogue record of the document. In a classified catalogue the main entry will be the subject entry in the classified sequence. In a dictionary catalogue the main entry will be as determined by AACR or whichever catalogue rules are in use - normally the principal author. Added entries will be made for additional access points or headings. For example, in an author catalogue added entries might be expected for collaborating authors, writers, editors, compilers and illustrators (see Chapter 9). Typically, added entries do not include all of the components of the description that are used in the main entry, but only the minimum needed for identification. The second approach is the use of unit entries; in a unit entry catalogue all entries are equivalent and contain the same descriptive detail. This approach is commonly found in card catalogues. Printed catalogues and indexes tend to prefer the main and added entry format, which uses less space.

Entries are usually supplemented by references. A reference provides no direct information about a document but, rather, refers the user to another location or entry. References take less space than added entries in a printed index, and require less detail to be printed on a card. There are two types of reference: see and see also. These operate in a similar way whether they are used to link authors’ names or subject headings.

A see reference directs the user from a name, title, subject or other term which has not been used as an entry heading to an alternative term at which words occur as a heading or descriptor. See references may link two subjects with similar meanings (for example, Currency see Money) or variant author names (for example, Council for the Education and Training of Health Visitors see Great Britain. Council for the Education and Training of Health Visitors). Some bibliographies use references in situations where AACR would require an added entry, as with second authors. For example, the added entry:

Frink, Elisabeth Frink / Edward Lucie-Smith and Elisabeth Frink. -Bloomsbury, 1994. - 138p. - ISBN 0-7475-1572-7

from Figure 3.7 would be replaced with the reference

Frink, Elisabeth see Lucie-Smith, Edward and Frink, Elisabeth

A see also reference connects subject headings or index terms which have a hierarchical or associative relationship (Chapter 5). For example, the following see also reference links two headings under which entries may be found:

Monasteries see also Abbeys

The searcher is recommended to examine entries under both index terms if it is likely that documents might prove to be relevant. See also references between personal names, corporate bodies and uniform titles are prescribed also by AACR in a very limited number of circumstances, for example, where the same person’s works are listed under different pseudonyms or where a corporate body has changed its name.

Explanatory references may be either see or see also references that give a little more detail than merely the direction to look elsewhere. An example might be:

Devon, Sarah

For works of this author published under other names see

Murray, Jill; Treves, Kathleen.

Association of Assistant Librarians

See also the later name:

Library Association. Career Development Group

Creating and Searching Printed Indexes

One of the first applications of computers in information retrieval was in the production of printed indexes. Computers were used for in-house indexes to reports lists, local abstracting and indexing bulletins, patents lists, etc. and for the production of published indexes to many of the major abstracting journals. Particularly for the large abstracting and indexing organizations, computerization of indexes and indexing yielded considerable savings in the production and cumulating of indexes. Originally index production was an isolated operation. Now, many indexes are merely one of a range of database products.

In spite of the growth of online searching, for some time yet there will be searches in which reference to a printed index is cheaper and simpler. Several different access points may be used in printed indexes. The most important of these are subject and author; but chemical formulae, trade names, company names and patent numbers are all possible access points.

All indexes consist of a series of lead terms, arranged usually in alphabetical order. Each lead term may be qualified and must have a link that leads the user to other lists or documents. Computer-generated indexes may rely on automatically assigned index terms or intellectually assigned terms. Each of these possibilities will now be considered.

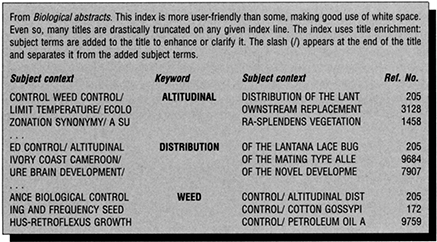

Keyword Indexes

A KWIC index is the most basic of natural-language indexes. KWIC or keyword in title (KWTI) indexes are popular because they are straightforward and relatively cheap to create. In the most basic of KWIC indexes, words in a title are compared with a stoplist, in order to suppress the generation of useless index entries. The stoplist or stopword list contains words under which entries are not required, such as: them, his, her, and. Each word in the title is compared with those in the stoplist and if a match occurs it is rejected; but if no match is found, the term is designated a keyword. These keywords are used as entry words, with one entry relating to the document for each word. The word is printed in context with the remainder of the title (including stopwords). Entry words are arranged alphabetically and aligned in the centre or left column. A single line entry, including title and source reference, is produced for each significant word in the title. The source reference frequently amounts to no more than a document or abstract number, but may extend to an abbreviated journal citation. Alternatively, a full bibliographic description, with or without abstract, can be located in a separate listing. Entries under one word are arranged alphabetically by title. Figure 12.1 presents an example of a KWIC index layout.

Figure 12.1 KWIC index

The merits of title indexes derive mainly from the low human intervention. Since a simple KWIC index is entirely computer generated, a large number of titles can be processed quickly and cheaply. The elimination of personal interpretation enhances consistency and predictability. Indexing based on words in titles reflects current terminology, automatically evolving with the use of the terminology. Also, the creation of cumulative indexes (to, say, cover five-yearly annual volumes) is easier and does not demand any added intellectual effort, only an extra computer run.

However, for all their convenience, title indexes are open to criticism on several counts:

Titles do not accurately mirror the content of a document. Titles can always be found which are misleading or eye-catching rather than informative, e.g. The black/white divide’ (politics or graphics?).

Basic KWIC indexes are unattractive and uncomfortable to read, due to their physical arrangement and typeface.

Many KWIC indexes display only part of a title.

Subarrangement at entry terms would also improve the scannability and searchability of KWIC indexes, by breaking down long sequences of entries under the same keyword.

The remainder of the criticisms of title indexes is concerned with the absence of terminology control. Irrelevant and redundant entries are inevitable. The mere appearance of a term in a title does not necessarily herald the treatment of a topic at any length in the body of the text Further, even when the term assigned is relevant, with no terminology control, all the problems, which a controlled language aims to counter, re-emerge. Subjects will be scattered under a variety of terms with similar meanings. No directions are inserted between related subjects.

The more sophisticated KWIC-type programs attempt to negotiate these limitations. Readability can be improved by simply altering the printed format A KWOC index, for instance, extracts the keyword from the title; the keyword is used as a separate heading, with titles and accession numbers listed beneath it. An asterisk sometimes replaces the keyword in the printed title. Indexes where the keyword appears both as heading and in the title are strictly keyword and context (KWAC) indexes, but this distinction is rarely made, and KWOC is the generic term used. Subarrangement at entry terms further enhances scannability. The index user is released from the necessity of scanning every entry associated with an index term and can select relevant entries by the alphabetical arrangement of qualifying terms. Both Permuterm and double-KWIC indexes provide a solution.

The Permuterm index (as used in Science and Social Sciences Citation Indexes) is based on pairs of significant words extracted from the title. All pairs of significant terms in a title are used as the basis of index entries; such pairs are arranged alphabetically with respect to each other. An accession number accompanies each pair but no title. Accession numbers, titles and other information are printed in a separate listing. Similar paired listings can also be used in searching the electronic database associated with Science and other Citation Indexes.

Double-KWIC indexes also give subarrangement at entry terms, but are fuller than a Permuterm index in that the title is displayed as part of the entries in the index. Their extreme bulkiness prevented them from gaining any significant popularity.

More refined computer-indexing packages instil a degree of control into the selection of index terms. By widening the indexing field, terms from free or controlled vocabularies may be added to the title and treated in the same way as terms in the title. Alternatively, specific terms in the remainder of the record in, say, the abstract, may be marked by the indexer to be used as terms to augment the index terms in the title. Further control may be exercised in such a way that all of the keywords under which index entries are to be found can be designated manually, prior to input. Exerting this amount of control tends to undermine most of the advantages of title indexing, but does provide for terms being assigned in accordance with the document being indexed and its content, rather than arbitrarily assigning a term as an index term merely because it appears in a record. Also, with control, terms may be signalled as comprising more than one word, e.g. international economics, since two words can be signalled as being linked.

Indexes Based on String Manipulation

Controlled indexing languages (such as may be recorded in thesauri and lists of subject headings, see Chapters 5 and 6) are still preferred by many index producers including, for example, Index Medicus, Science Abstracts, Engineering Index and the British National Bibliography. Nevertheless, the computer still has a role in the production of indexes based on intellectually assigned index terms, by formatting and printing such indexes, and particularly in making cumulations. In addition, the computer has a hand in the generation of indexes based on string manipulation. Here, the human indexer selects a string of index terms from which the computer, under appropriate instructions, prints a series of entries for the document to which the string of index terms relate. The techniques of pre-coordinated subject headings have been described in Chapter 6.

Citation Indexes

Citation indexing is a means of producing an effective index by exploiting the computer’s capacity for arranging and reformatting entries. Input to the indexing system comprises the references of recent articles in relatively few core journals and, for each article, the list of works that it refers to. A citation index then lists cited documents together with a list of those items that have cited them (citing articles). This is an effective way of covering a fairly wide subject field with almost no human intervention. The prime examples of citation indexes are those produced by the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), i.e., Social sciences, Arts and humanities, and Science citation indexes. Thus, given one document in a field, the searcher should be able to trace other related documents. However, the many inconsistencies in citation standards cause problems, and the reasons for citing a document are not always to do with shared subject content. While citation indexes started life as printed products, most users now encounter citation in databases, such as those produced by ISI, that include citation links. In this context, citation links can provide a valuable additional approach to the identification of related documents.

Searching Printed Indexes

Many of us today are so accustomed to conducting all our searches via the terminal that the techniques specific to printed indexes are apt to be forgotten. This brief checklist of practical factors to be aware of supplements the more generalized account in ‘Manual and computerized catalogues and indexes compared’ above.

Coverage. Check - either by examining any prefatory material or by direct inspection - how the subject (or other) field has been defined, and what range of material is included. If the coverage appears marginal to the information need, then either bear this in mind when searching or check literature guides and other secondary sources for more appropriate indexes. Is retrospective coverage adequate? Be aware that a long retrospective search through annual cumulations will be slow, repetitive and often heavy work.

Depth of treatment. Are there indexes only, or are there abstracts also? How exhaustive is the indexing? If there are abstracts, are they informative or merely indicative? In many cases, where there are print and electronic formats of the same database, the printed index will offer far fewer search keys, even within the same field - for example, by not making minor descriptors available for searching.

Up-to-dateness. Some abstracting journals have a time-lag of several months or even a year or two. Verify by spot-checking. If unacceptably dilatory, then see if more up-to-date hard-copy alternatives are available: for example, the Current Contents series of indexes. Otherwise, networked electronic files are usually more up to date than hard copy.

Arrangement. Indexes are basically either one-stage or two-stage.

- A one-stage, or dictionary, index has all approaches interfiled in a single A-Z sequence. Avariant has a single A-Z subject sequence with a separate author index.

- A two-stage index has (1) a bibliography (citations with or without abstracts), often in a broadly classified subject grouping to permit browsing. For specific searching the bibliography is accessible via (2) author and subject indexes; occasionally other indexes also. Author indexes may give a full citation; more usually just a reference. Depending on the nature of the subject, other specialist indexes may be found, e.g., the Biosystematic index in Biological Abstracts.

Subject approaches. These are often very limited, certainly compared with electronic versions. There is a great variety of styles, of which this is a very crude typology:

- Keyword indexes, usually based on titles. At their best, the title will appear in full at each access point, perhaps with title enrichment; at their most basic, there will be a simple keyword index.

- Heading consisting of a word or phrase expressing a single concept, e.g., CLUMSY CHILDREN. Indexes of this type are primarily intended for machine searching, the printed versions being a by-product and nothing more. Examples: British Education Index, Information Science Abstracts.

- Heading + single subheading, e.g., FOOTBALL - INJURIES. Examples: Index Medicus; Engineering Index.

- Heading + a variable number of subheadings, but rarely exceeding three facets in all. Examples: any catalogue or index based on the Library of Congress Subject Headings; subject indexes based on the Dewey Decimal Classification; also most H. W. Wilson indexes, e.g., Cumulative Book Index, Library Literature.

- Fully faceted systems, allowing complete flexibility to express complex subjects. Examples: the PRECIS system, used to index BNB between 1971 and 1990; Abstracts in New Technologies and Engineering (ASSIA uses the same system).

Scatter in subject indexes. A limitation of rotated indexes of all kinds is that the citation order used for indexing may not match the search pattern. For example, if a searcher has in mind: ‘Football in Scotland’, an index may or may not have entries at, say,

Football. Scotland

and at

Football. Management Clubs. Scotland.

It is easy to overlook the second entry, particularly if it is surrounded with a mass of similar-looking entries in close print.

Other Points to Check

Use library catalogues and guides, literature guides etc. to ascertain what is available in the subject area. Check both hard copy and electronic sources.

Instructions for using indexes are often found at the front of the index. Sometimes there are separate guides, from the publisher or produced by the library, or even video tutorials for the more complex indexes.

Layout and arrangement of bound volumes and unbound issues. How do the issues cumulate? Are the indexes in separate volumes? Current (uncumulated) issues of many abstracting journals may lack some or all indexes.

Be aware of the filing rules in use.

For subject searches, start with the most recent issue and work systematically back.

If there is an accompanying thesaurus, use it to suggest alternative approaches.

Do not expect too much of printed indexes. Many are less exhaustively indexed than their electronic versions, and increasingly printed indexes may not be designed for easy use.

Know when to stop. The Law of Diminishing Returns applies. At what point do citations become so old as to cease to be useful?

Book Indexing

Book indexes are one type of printed index. They are important in assisting the user to locate concepts within the text of a book. Since book indexes can be compiled by authors, or by professional indexers, the quality of such indexes varies considerably. A small extract from an index in a book (a book on indexing) was given in Figure 5.2. Entries may be the names of persons, corporate bodes or places, or alphabetical index terms to represent subjects, Mowed by number of those pages on which the information is to be located.

The purposes of an index are, according to the relevant British Standard (BS 3700:1988), to:

identify and locate relevant information within the material being indexed

discriminate between information on a subject and passing mention of a subject

exclude passing mention of subjects that offers nothing significant to the potential user

analyse concepts treated in the document so as to produce a series of headings based on its terminology

indicate relationships between concepts

group together information on subjects that is scattered by the arrangement of the document

synthesize headings and subheadings into entries

direct the user seeking information under terms not chosen for the index entries to the headings that have been chosen, by means of cross-references

arrange entries into a systematic and helpful order.

The same principles can be used to guide the creation of entries in book indexes, as are outlined elsewhere in this book. The indexer creates an informal controlled vocabulary, one that is based on the language used by the author. Headings for person, places and corporate bodies can follow the model offered by AACR in matters such as the identification of best known names and the use of abbreviations of names. For subject entries, the problems associated with the variability of language and the indication of relationships between subjects still need to be addressed. Figure 5.2 shows clearly how the index groups together subjects that the document scatters. In this particular index the grouping is assisted by the frequent use of see also references (not shown in Figure 5.2), for example:

alphabetization see also filing order; sorting.

See references are also found, as:

audience see readers.

Where subentries have been used, the indexer should provide appropriate access points. For example, the index used in Figure 5.2 also has such entries as:

alphabetization

of abbreviations, 130

and

double-posting

of abbreviations, 130

Indexes should subdivide entries rather than offer long lists of page numbers. Any main heading with more than five or six reference locators should be considered for subentries, as long undifferentiated lists of page or section numbers are a hindrance to the user.

Many word-processing packages support an indexing function, but they are relatively unsophisticated. Index entries are made either by applying a markup code to keywords in the text, or by embedding in the text words or phrases that will appear as index entries only. Dedicated indexing software is available in a variety of packages (CINDEX, Indexer’s Assistant, MACREX, among others), and is recommended for all but the simplest indexes. The features found in dedicated software include:

Editing and display features: copying a previous entry; transposing (flipping) main heading and subheading; searching and find-and-replace entries; creating a subset of the index for the indexer to work on; verifying cross-references; onscreen editing.

Sorting features: word-by-word or letter-by-letter alphabetizing, immediate sorting of entries, page number sort, merging of index files.

Formatting and printing features: removal of duplicate entries or page references; automatic formatting and printing of the index in a range of styles, including user-selected formats; creation of user-defined style sheets.

Exhaustive of Indexing and Specificity

The indexer is required to judge which items of information are relevant and which are to be passed over. The depth of indexing required will be affected by the nature and length of the book. An average ratio of index pages to text pages is 3 per cent, but for reference books this may be much higher. A well-structured book may be easier to index than a less well-structured one. Specificity of index headings can also be guided by the content of the book.

Filing Order and Sequences

Earlier sections have considered in some detail the headings and search keys to be used in catalogues and indexes. In any situation where a number of such headings or terms are to be displayed one after another in a static list, some well-recognized filing order must be adopted. Thus in printed and card catalogues and indexes, the filing order is important in assisting the user in the location of a specific heading or term. In computer-based systems, lists of index terms or search keys are sometimes encountered, and here it is also useful to work with a defined filing order, especially where a large collection or database is being indexed. If no filing order is adopted, the only way in which appropriate headings and their associated records can be retrieved is by scanning the entire file.

Since most headings in catalogues and indexes comprise primarily Arabic numbers and letters of the roman and other alphabets, it is these characters that must be organized and for which a filing order must be defined. While the letters of the alphabet do have a canonical order, letters, unlike numbers, are not primarily handled for their ordinal values. The larger the file, the slower and more complex the consultation process, and some users will have difficulty finding their way through large, complex files. As much help and assistance should be given, both within and outside the catalogue or index, as is reasonably possible.

Maintaining a coherent sequence requires, first, a set of filing rules. It also requires that these rules be followed accurately and consistently. In many printed indexes filing is done by program, which does ensure absolute consistency once the program has been instructed on the desired filing order. Such programs must take account of human expectations, which may conflict with unmediated machine procedures. For example, most character sets give upper case letters a lower numeric value than lower case, which would make Great Britain file before Great apes if there were no machine instruction to ignore case. Modern software mostly takes care of problems at this level; but other problems may be encountered at higher levels. A very common one is to try to manipulate numbers within an alphanumeric character set, which produces the sequence 1, 10, 100, … 11, … 12, … 2, … 3 etc. Machine filing also requires accurate data: the accidental omission of a space or a comma from a heading at the time of data entry can result in a record being filed way out of sequence.

Where filing is done manually, which is slow and expensive, the need for accuracy is critical. Nowhere is this more so than in the card index, where only one record is visible at a time, and a single misfiled card seems to acquire a magnetic attraction for other cards, causing it to grow into a substantial double sequence which may lurk undetected for years. Card indexes, and the physical location of documents, are the places where manual filing is most likely to be encountered.

Modern filing rules take into account the requirements of machine filing. There has been a welcome tendency to simplify procedures: rules such as the ALA Rules for Filing Catalog Cards (2nd edn, 1968) had grown pedantically complex.

Problems and Principles in Alphabetical Filing Sequences

Filing value of spaces and punctuation symbols

If spaces between words are given a filing value, word-by-word filing results; if not, the order is letter-by-letter. These give:

Word-by-word |

Letter-by-letter |

Leg at each corner |

Legal writing |

Leg ulcers |

Leg at each corner |

Legal writing |

Legends of King Arthur |

Legends of King Arthur |

Leg ulcers |

Word-by-word order is the more common, at least in the English language, but letter-by-letter filing is by no means dead. Hyphenated words are a related problem: where would Leg-irons file within either of the above sequences? And dashes also, which are not the same as hyphens: how would Leg - bibliographies file?

Acronyms fall within this category, as their filing value may be affected by whether they incorporate full stops and possibly spaces. Does ALA. file near the head of the sequence of As or somewhere between Al Capone and Alabama? What if it is written A. L A? Or ALA? Or ALA?

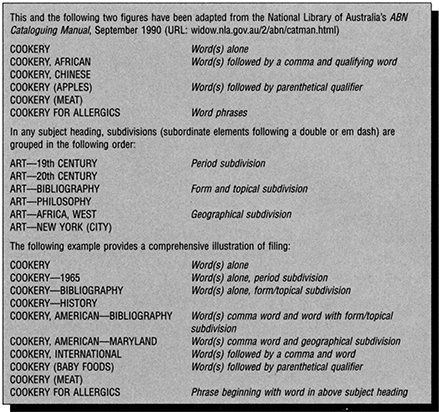

Subject headings beginning with the same word may be interfiled in different ways according to the filing value given to inverted headings, phrase headings and subdivided headings. Frequently the filing value accorded to a subdivided heading (where the punctuation is a dash) may be different from that for inverted headings (which use commas), which may lead to deviations form the strict and most obvious alphabetical sequence. Where certain symbols have a filing value, they introduce a classified element into an alphabetical file (Figure 12.2).

‘As if and ‘File as is’ filing

Some kinds of character string may file otherwise than as given. Filing rules designed with automated filing in mind tend to minimize the amount of ‘as if’ filing, and to file as given in most cases. Examples include:

abbreviations, particularly of terms of address: for example, Dr and St filing as Doctor and Saint

ampersands (&) may file as they stand - ampersand generally files before numbers and letters. ‘As if filing would have to translate & as and, et, und etc., according to the language of the document

diacriticals: should Muller file as Muller or Mueller? ligatures also: does Æthelred file under E or A? ‘As if’ filing uses the first, ‘As is’ the second, in each case

Figure 12.2 Filing values of subject headings

numbers: should Arabic numbers file as numbers, in a sequence preceding letters? In an ordinal sequence, or as characters? Should roman numbers file as numbers or as letters? And if as letters, how will this affect the filing of headings like Bus VIII, pope and Pius K, pope? How should more complicated numbers, or strings containing numbers and other characters (e.g., $50, 1/10, 3rd, πr2, 0.5), file?

Scottish and Irish names beginning with Mac and variants: filing rules of British origin often interfile Scottish and Irish names beginning with Mac, Me, Mc, and M’.

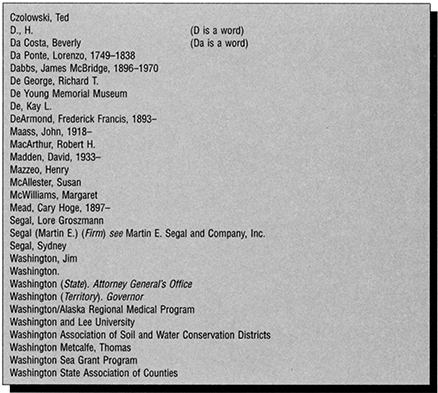

Figure 12.3 Comprehensive punctuation and filing in the author index

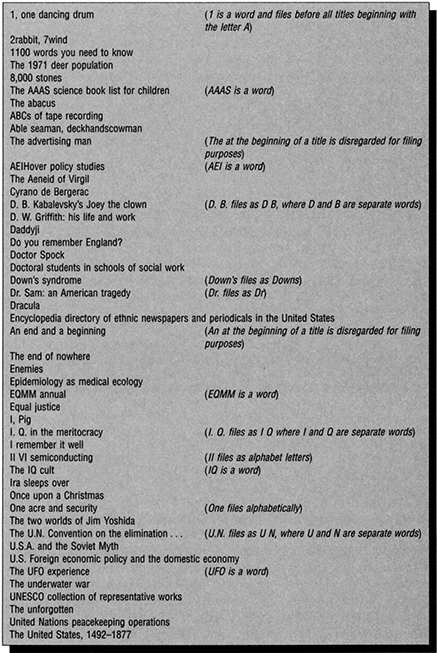

Non-filing elements

Many headings include an additional non-filing element. Most commonly, definite and indefinite articles (The, A, An) at the beginning of titles are ignored. Some text management systems incorporate in their sort procedures a routine for automatically ignoring initial articles - or more precisely, title strings beginning with A An or The. This is satisfactory provided all the titles are in the same language, though even here there could be the occasional misfit of the type A Apple pie. Another non-filing element commonly met is Sir etc. in British titles of honour of the type: Reynolds, Sir Joshua.

Many of the problems touched on here are illustrated in Figures 12.3 and 12.4.

Figure 12.4 Comprehensive punctuation and filing in the title index

Different types of headings beginning with the same word

Headings may arise as author, title and subject, and all types of headings may commence with the same word. ‘Black’, ‘Rose’, ‘London’ are all words that could be part of author, title or subject headings. The problem is whether to adopt a strict alphabetical sequence or whether the user would find it helpful to have entries of the same type grouped together.

Arrangement of entries under the same heading

A prolific author may be responsible for a number of books, or a subject heading may be assigned to several books that discuss the same subject. The preferred sequence for multiple entries under the same heading or term needs to be established. First, it is normal to distinguish between references and added entries, and then to group references at the beginning of the sequence associated with a given term or heading. Next, it is necessary to order the works for which entries are made under a specific subject or author heading. Often the title is used for this purpose but, sometimes, chronological order may be preferred.

Summary

It is a measure of the growth of machine searching that for this edition we have seen fit to relegate manual searching to a single chapter near the end of the book. In particular, the rapid growth of the World Wide Web into a single platform for services that until very recently had to be consulted by using OPACs, CD-ROMs, command-based online search services or bound volumes, has introduced an element of one-stop shopping into our information needs and has led to a growing attitude that any information that cannot be located electronically is not worth searching for at all.

This is an unsound attitude, for a number of reasons. First, there are many parts of the world where the infrastructure to support machine-based systems is inadequate or lacking. Even in developed areas there may be power failures or system downtime. Second, many information resources are still only available in hard copy. Many of these are very specialized, either because they appeal to a small clientele or because they extend a long way back in time (which amounts to much the same thing). Next, the permanence and browsability of hard-copy sources aid serendipity and creativity. Finally, only printed sources are fully portable and lend themselves to continuous consultation. To that extent, this chapter does not relegate manual searching, but serves to draw attention to it.

References and Further Reading

American Library Association (1980) ALA Filing Rules. Chicago: ALA.

British Standard Institution. (1985) British Standard Recommendation for Alphabetical Arrangement and the Filing Order of Numbers and Symbols. BS 1749:1985. London: British Standard Institution.

British Standard Institution. (1988) British Standard Recommendation for Preparing Indexes to Books, Periodicals and Other Documents. BS 3700:1988. London: British Standard Institution.

Cleveland, D. B. and Cleveland, A. (1990) Introduction to Indexing and Abstracting, 2nd edn. Littleton, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Knight, G. N. (1979) Indexing, the Art of. London: Allen and Unwin.

Mulvany, N. C. (1994) Indexing Books. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wellisch, H. (1991) Indexing from A to Z. New York: H. W. Wilson.