9

Access points in catalogues and bibliographies

Introduction

This chapter draws together strands from earlier chapters. Chapter 3 examined document representation, including record formats, bibliographic description and the structure of the MARC record. This chapter examines document access in the context of catalogues and bibliographies. Access points, called headings, in catalogues and bibliographies use a special kind of controlled language: one that is confined to proper names and is governed not by a thesaurus but by cataloguing rules. Cataloguing rules are quite different in structure and appearance from thesauri; and whereas there exists a large range of special purpose thesauri, in most of the world there is just one cataloguing code: the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, first published in 1967, extensively revised in 1978 (AACR2), and reissued with minor revisions in 1988 and 1998. As was explained in Chapter 3, Part 1 of AACR2 addresses document description. Part 2, entitled ‘Headings, Uniform Titles, and References’, addresses document access.

This chapter, then, aims to give you a critical awareness of cataloguing rules governing access points. You will learn:

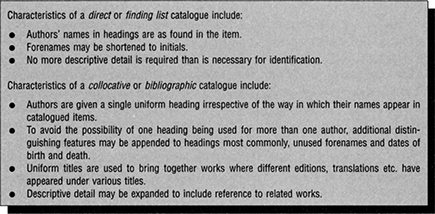

the functions of catalogues, and the conflict between the ‘direct’ or ‘finding list’ and ‘collocative’ or ‘bibliographic’ functions

the structure of Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules

the ‘cases’ and ‘conditions’ approaches to catalogue rule construction

the principles of main and added entries

how headings for persons, corporate bodies and uniform titles are structured

how to make and use references in catalogues.

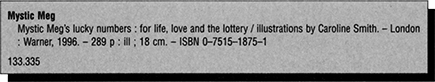

Figure 9.1 Sample catalogue entry

What is a Catalogue?

A catalogue is a list of the documents in a library, with the entries representing the documents arranged for access in some systematic order. Catalogues, today, are often held as a computer database, usually called an OPAC. Otherwise, a catalogue may be held as a card catalogue, or on microform, or as a printed book.

A catalogue comprises a number of entries, each of which is an access point for a document. A document may have several entries, or just one.

The entry shown in Figure 9.1 has, like all catalogue entries, three sections:

heading: this is the access point, the element under which the record is filed

description, identifying and further characterizing the item

shelfrnark: a mark identifying the physical location of the item within the collection.

The presence or absence of a shelfmark is the most obvious distinguishing feature between a record in a catalogue and one in a bibliography. Bibliographies are not normally limited to items in one collection, and so the records in a bibliography do not carry shelfmarks.

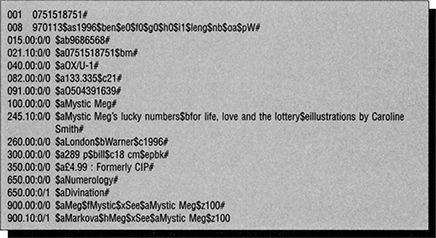

The entry is derived from a MARC record: the same record that was used in Figure 3.8, and is displayed again in Figure 9.2.

In this MARC record, the access points are determined as follows:

100.00:0/0 |

the 100 field determines a personal author main entry heading. |

245.10:0/0 |

1 in the first indicator position of a 245 (title) field indicates that an entry is required under the title. |

900.00:0/0 |

This field shows that references are required. The first reference is from an inverted form of the author’s name. The second is from her real name to her given name. |

The MARC record also gives subject access points (field 650), which were described in Chapter 6.

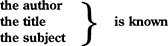

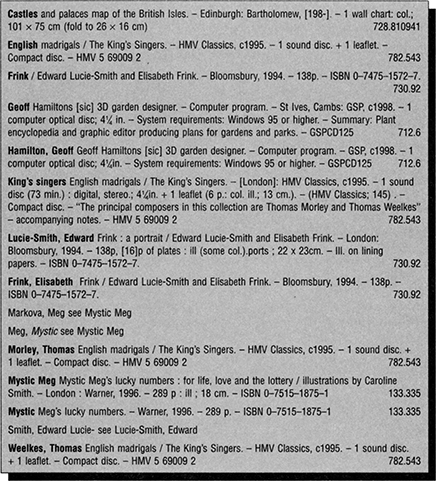

In an author/title catalogue or bibliography, entries for persons, corporate bodies, and titles are filed alphabetically, together with references from unused names or forms of a name. Figure 9.3 shows a mini-catalogue containing just five works, all taken from the example in Figure 3.6. (For simplicity, Level 1 descriptions have been used for the added entries):

Figure 9.2 MARC record from which the catalogue entry in Figure 9.1 was derived

Functions of Catalogues

As explained in Chapter 6, the functions of a catalogue were systematically defined over a century ago by Charles Ammi Cutter, whose Rules for a Dictionary Catalogue (fourth edition, 1904) is one of the seminal works of the information and library profession - and remains highly readable today. Cutter’s is the classic analysis, and is still widely accepted, at least as the starting-point for a definition of the functions of a catalogue:

1. To enable a person to find a book of which either

Cutter oversimplifies. No single one of these attributes (except sometimes the title) can be relied on to find a book. In practice two are needed: author + title, or author + subject, or title + subject. With the increased availability of keywords as identifying elements in online searches, it is no longer necessary to know the first word of an author, title or subject heading.

Otherwise, Cutter’s basic definition of the catalogue as a finding list to the contents of a library or library system still holds good, but with the reservation that in recent years attitudes to retrieval have become access based rather than collection based, so that many catalogues range more widely than their own collections. Also, most library catalogues now include not only books but other materials as well, particularly audiovisual materials (films, videos, tapes, slides, etc.); only occasionally are there separate catalogues for these. Catalogues did not and do not normally list the contents of books or serials. For serials normally only the title of the serial as a whole is catalogued, and other indexes identify the individual articles.

Figure 9.3 Author/title catalogue

The catalogue is primarily a finding list for known-item searches. It gives direct access to a specific document, details of which are known to the searcher, and in the past often constituted a library’s administrative record of its stock. This type of catalogue has been variously labelled a direct catalogue, finding-list catalogue, or inventory catalogue. This group of functions is valid for both manual and machine-searchable catalogues. The latter usually offer extended facilities for known-item searches (e.g., author/title acronym; title keywords; control number).

Card catalogues in the UK traditionally only provided title access points for a small proportion of their stock. Many UK catalogues were described as name catalogues, containing entries under authors and under personal names as subjects.

A subject search is not usually a known-item search, unless the subject is the only retrievable fact known about a half-forgotten item (‘… a slim green volume on fly-fishing, written by J. R. somebody-or-other…’). Since Cutter’s day, subject and author approaches have come to be contrasted. In the one, the requester usually has a specific item in mind. In the other, there is only an information need, and no specific item or items can be identified until a selection of hopefully relevant items has been found. Catalogue codes after Cutter have excluded the subject approach.

2. To show what the library has:

by a given author…

This has caused, and continues to cause, endless confusion in catalogues. Many authors use or are known by variants on their name (George Bernard Shaw; Bernard Shaw; G. B. Shaw; even G.B.S.) or even by two or more completely different names (Anthony Eden; Earl of Avon). Cutter implies that all the works of a given author must appear in a catalogue under a single unique and uniform heading.

A catalogue that sets out to fulfil these functions is called a collocative or bibliographic catalogue. This group of functions has long been recognized as being far subordinate to the finding-list function (Figure 9.4). Advances in bibliography over the past century have meant that there is now far less need for a catalogue to provide this kind of service than there was in Cutter’s time. However, much networked catalogue copy is produced by national bibliographic agencies (e.g., the British Library), whose primary function is to produce a national bibliography which will correctly and uniquely ascribe each work to its author.

Current cataloguing rules (AACR2) try to reconcile this tension (see the discussion at the end of this chapter); but essentially the bibliographic tail continues to wag the finding-list dog in the majority of our catalogues.

Figure 9.4 Direct and collocative catalogues

…on a given subject…

Nearly all catalogues offer a subject approach. ‘On a given subject’ is a delightfully simple phrase, implying that the subject of a published item can be adequately summed up in a single word or short phrase. This might have sufficed a century ago, but it is ill equipped to express the complexities of current publishing and scholarship. However, such is the weight of tradition that it is largely through Cutter’s influence that the subject approaches available in library catalogues today are simplistic, crude and superficial. (Notice, again, that AACR2 does not deal with the subject approach.)

… in a given kind of literature.

Catalogues are mostly well equipped to tell the user if a book is prose or poetry, or even (say) German poetry. In other respects (e.g., all books written in German; all humorous books; all biographies) catalogues today are less helpful. The MARC record format does however provide for these (and other) approaches.

3. To assist in the choice of a book:

as to its edition…

It is basic to the function of a catalogue to be able to identify each item uniquely, and the need for catalogues to indicate the edition of a work is undisputed. Beyond this, full descriptive cataloguing (AACR2’s Levels 2 and 3) provides for considerably more detail than is needed for identification. Such elements as subtitle, series title, physical description (pagination etc.) and (usually) notes serve to characterize rather than to identify, and some library catalogues exclude them as a matter of policy.

… as to its character (literary or topical)

Cutter had annotations in mind when he wrote this. A century ago, libraries kept their stock on closed access, and every item had to be individually requested. Under these conditions, suitably annotated catalogue entries were considered well worth while in giving readers some better idea of what they were requesting, and so saving the time and shoe-leather of library clerks scurrying to and fro in the stacks. Open access and plastic jackets have removed the need to annotate catalogue entries routinely. The practice survived sporadically into the 1960s, but is now confined to special subject lists in libraries, and to catalogue entries for videos, CD-ROMs and similar non-browsable materials.

Access to items of information by the names of the persons responsible for their intellectual content has a long and complex history. The need for a code of practice was powerfully established a century and a half ago by Antonio Panizzi, who as Keeper of Printed Books in the British Museum Library had to persuade the trustees of the need for the complex rules he was proposing to introduce. This he did by sending each of them off separately with copies of the same books, to catalogue them; and on their return he pointed out to them how each of them had done it quite differently.

The problems of personal names, as of corporate bodies, are, as Panizzi told his trustees, essentially two: agreeing on the name to be used, and establishing its entry element and other factors affecting its filing position in an alphabetical list an these respects the rules governing the author approach are the standard thesaural rules of vocabulary control extended to proper names.) These problems are as real today as they were in Panizzi’s day, though societal and technological changes have emphasized different aspects of them. With personal names, the problems addressed by Panizzi and his successors as compilers of catalogue codes for a full century were predominantly historical: what name to use for a nobleman; how to enter classical writers; whether to use the vernacular or Latinized form of name of writers like Linnaeus, and so on. We today tend to be more occupied with the problems of reconciling all the varied traditions of contemporary personal names in the global society. In the case of factors affecting filing, technology has removed many of the old problems. With keyword access, the filing element of Muhammad Ali or Chiang Kai-shek is no longer an issue.

While the author approach is traditionally associated with library catalogues, listings other than author indexes or catalogues also involve the arranging of entries according to the names of persons or organizations. Telephone directories are an obvious example, and there are many trade directories and similar publications that are alphabetically arranged. Even in this era of machine searching, there is still a significant place for manually searched, alphabetically arranged databases.

Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules

Two early sets of cataloguing rules have been mentioned so far: Panizzi’s British Museum Rules of 1841, and Cutter’s Rules for a Dictionary Catalog, first published in 1876. Other significant codes of rules have included the Anglo-American Code of 1908 (AA1908), and the American Library Association Code of 1949 (ALA1949).

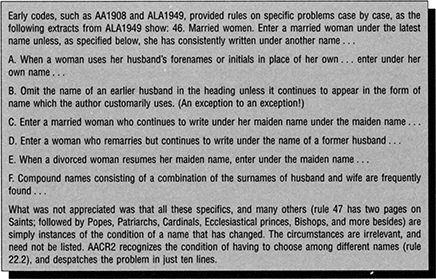

These codes were all based on the ‘cases’ approach whereby specific procedures were ordained to deal with specific problems (see Figure 9.5), and cataloguers faced with a problem that was not specifically covered by a rule had to proceed as best they could by analogy - there were even published special interleaved editions of the rules for cataloguers to add their marginal glosses.

The futility of the ‘cases’ approach was exposed in detail in 1953 by Seymour Lubetzky. He proposed instead a simpler set of ‘conditions’ or principles to guide the cataloguer. These were debated in detail by an International Conference on Cataloguing Principles held in Paris in 1961 - a landmark in the history of universal bibliographic control. The code which eventually emerged - the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules of 1967 (AACR1) - is based on the ‘conditions’ approach. The Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules received a thorough revision in 1978 (AACR2), and was reissued with minor revisions in 1988 (AACR2R) and 1998. This last is available in print (AACR2R2) and CD-ROM (AACR2e). A Concise AACR2 is also published. AACR2R2 incorporates a number of corrections and changes authorized by the Joint Steering Committee of AACR since the 1988 revision. (The acronym becomes more and more unwieldy with each successive issue. We shall refer simply to AACR2.)

Figure 9.5 The ‘cases’ approach to catalogue code compilation

Structure of AACR2

Throughout this section, Concise AACR2 equivalent rules are given in italics. This section will be easier to understand if a copy of AACR2 is to hand.

The rules follow the sequence of cataloguers’ operations, and proceed throughout from general to specific. The sequence is:

Description: The first step is to create a description based on the chief source of information (e.g., title page) of the item being catalogued. The description will normally contain enough information to explain the access points (headings) under which it is filed.

Choice of access points thus follows description. An access point may be a person, a corporate body, or a title. A work is likely to have more than one access point, typically two or three.

Headings. The cataloguer may have to choose between different names, or variant forms of the same name, or between different entry (filing) elements for any of the chosen access points.

References. Finally, references are needed for the guidance of catalogue users who approach the catalogue under a name or filing element other than the one that has been used.

Choice of Access Points

The concept of the access point belongs to manually searched indexes, and is arguably irrelevant to databases with search systems allowing keyword access. In manual indexes where every access point requires physical space, it is economically only possible to list a work in a limited number of places - very seldom more than five or six. The general principle is to provide access points under the significant persons and corporate bodies, and under titles, shown in the description.

One of these access points is traditionally designated the main entry, and all other approaches are by definition added entries. The original concept of main entry was partly administrative, partly intellectual. Administratively, the main entry in a card catalogue might carry ‘tracings’ - notes at the foot, or on the reverse, of the card, showing where the added entries were filed, so that the catalogue could be properly updated whenever a work was discarded or its catalogue entry amended. Intellectually, main entry was selected on the basis of the author ‘chiefly responsible for the creation of the intellectual or artistic content of a work’ (21.1A1). This principle is extended to works of corporate bodies. For the great majority of items, the main entry consists of a single personal author, which in a catalogue entry is followed immediately by the title - which follows our normal everyday practice of citing a work by its author and title.

The idea of main entry is thus a deep-rooted one, even though there is general acceptance that it has little relevance to modern cataloguing practice, and survives largely through being built into the structure of the MARC record. In most libraries, however, the main entry heading determines the shelving position of an item, as some kind of abbreviation (e.g., a Cutter number) forms partoftheshelfmark.

Most of Chapter 21 (i.e., 21.1-21.28) (21-28) is concerned with establishing Main Entry and distinguishing it from Added Entries. Do not overlook sections 29 and 30 (29), which deal specifically with added entries, as the rules for main entry include instructions for added entries only where these are specifically covered by the rule.

General Rule: 21.1 (23)

Main entry under a personal author or corporate body has to be justified on criteria of responsibility for the existence of the work; otherwise main entry is under title.

Works of Single Responsibility: 21.4 (19)

Single person 21.4A (24A)

Single corporate body 21.4B (24B)

Problems and special cases 21.4C-D

Personal authors are straightforward to define; corporate bodies (‘no body to kick, no soul to be damned’) are more elusive. AACR2 defines a corporate body as ‘an organization or a group of persons that is identified by a particular name and that acts, or may act, as an entity’. The designation of corporate author is studiously avoided. Instead, works are described as ‘emanating from’ one or more corporate bodies - the desperate verb, with its connotations of spiritualism and drains, warns of the many hair-splitting and sometimes arbitrary distinctions that are inevitably associated with corporate bodies. The general intention of rule 21.IB (main entry under corporate body) is clear enough: works dealing with the policies, procedures, operations or resources of the body, or which record or report its collective thought or activity. The specific rules on the other hand are fraught with provisos and special cases, making their consistent application very difficult in practice.

Here, as throughout AACR2, the examples are essential reading. They show how the problem or condition set out in the rule is applied to individual cases.

Works of Unknown or Uncertain Authorship, or by Unnamed Groups: 21.5(23C)

Main entry is under title. The second example under 21.5A (A Memorial to Congress against an increase of duties on importations/by citizens of Boston and vicinity) illustrates the definition of a corporate body: the group acted as an entity, but is not identified by a particular name. (Some earlier codes tried to invent a name: Boston. Citizens.)

Works of Shared Responsibility: 21.6 (25)

Shared responsibility is where two or more persons (or occasionally corporate bodies) have performed the same kind of activity. In cases where principal responsibility is indicated (usually by layout or typography), main entry is straightforward. Otherwise, an arbitrary rule is applied: if there are two or three contributors, main entry is under the first named, with added entries for the second and/or third. If there are four or more authors, main entry is under tide, with an added entry for the first named person or body only.

Citation practice is to name two authors, e.g., Aitchison, Jean and Gilchrist, Alan. Headings of this kind are not authorized by AACR2 and are not found in modern catalogues. The main entry would be under Aitchison, Jean with an added entry under Gilchrist, Alan.

Collections, and Works Produced Under the Direction of an Editor: 21.7 (26)

Editors of works consisting of contributions by different hands, and compilers of collections, are not regarded as having sufficient responsibility for their works to warrant main entry. In all cases, main entry is under title, with an added entry for the editor. If, however, a collection does not have a collective title, then main entry is made under the heading appropriate to the first contribution.

Mixed Responsibility: 21.8-21.28 (27)

Notice the spread of rules; unusually, AACR2 takes a case-by-case approach in this section. Mixed responsibility covers works to which different persons or bodies have contributed different kinds of activity. Two types of mixed responsibility are distinguished: works that are modifications of other works (e.g., adaptations, revisions, and translations); and new works (e.g., collaborations between artist and writer, interviews, and - wondrously, but such works exist -communications ‘presented as having been received from a spirit’ through a medium). Principal responsibility is usually assigned to the person or body (or spirit!) named first. However, at 21.10A covering adaptations of texts, main entry is under the heading for the adapter, to the annoyance of children’s librarians everywhere.

Related Works: 21.28 (28)

We now come to the sixth and last condition of authorship. Related works are separately catalogued works that have a relationship to another work. These include continuations and sequels, supplements, indexes, concordances, scenarios and screenplays, opera librettos, subseries, and special numbers from serials.

A related work is entered under its own appropriate heading, with an added entry under the work to which it is related. In some cases ‘name-title’ added entries are prescribed. These consist of the author and the title of the related work, for example,

Homer. Odyssey

for an adaptation that has a different main entry heading and title.

Added Entries: 1.29-21.30 (29)

The rule for added entries consolidates and expands on all the above. ‘Make an added entry under the heading for a person or corporate body or under a title if some users of the catalogue might look under that heading or title rather than under the main entry heading or title.’ Added entries are to be applied judiciously and sparingly - the rules are almost as much concerned with when not to make an added entry as when to make one - there is though a splendid catch-all at 21.29D: ‘If… an added entry is required under a heading or title other than those prescribed in 21.30, make it.’

The specific rules at 21.30 cover:

Two or more persons or corporate bodies involved. These include collaborators, editors, compilers, revisers, etc.; performers; and other related persons or bodies, such as the addressee of a collection of letters, or a museum where an exhibition is held. Corporate bodies warrant an added entry unless they function solely as distributor or manufacturer. Even so, an added entry is made for a publisher whose responsibility for the work extends beyond that of publishing.

Two or more persons or bodies sharing a function. Entries are made under all of them if there are no more than three. If there are four or more, an added entry is made only under the first.

Related works (which may need a name/title heading).

Other relationships if needed, unless the relationship between the name and the work is that of a subject The example given is that of an art collection from which reproductions of art works have been taken.

Titles (with a few exceptions); today’s automated catalogues will provide these automatically.

And if thought appropriate: translators, illustrators, series title, and analytical added entries (entries for separate works contained within the item being catalogued: a collection of plays for example) guidance is given on this.

Headings for Persons

Chapter 22 (31-43) is set out step by step. First, a choice may have to be made between different names by which the same person may be known. Second, once the name has been decided, the entry element must be decided. Finally, it may be necessary to make additions to names, to clarify the person’s identity or to distinguish the name from other similar names.

Choice of Name: 22.1-22.3 (31-32)

Many people use more than one name. They may be a completely different names, as with authors who change their names on marriage, or who use pseudonyms, or are known to their friends and to posterity by a soubriquet or nickname, as with the Venetian painter Jacopo Robusti, whose father was a dyer and so was called Tintoretto. Or the names may be variants, as with Tony (for Anthony) Blair, or Ovid (Publius Ovidius Naso), or W(illiam) Somerset Maugham. The general rule is to use ‘the name by which a person is commonly known from the chief sources of information of works by that person issued in his or her language’; otherwise from reference sources in his or her language or country.

The principle that a person can appear under only one form of heading is broken only in the case of pseudonyms (22.2B). This complex rule tries to allow for the fact that nobody can be certain how many authors are lurking in catalogues under one or more pseudonyms (Stendhal is said to have used 71). Established writers may have two or more separate bibliographic identities, as with Charles Luttwidge Dodgson the mathematician and Lewis Carroll the author of Alice in Wonderland; AACR2 allows such writers to retain their separate identities. In the case of contemporary authors, the basis for the heading is the name appearing in each work, with connecting references where two or more names are known to belong to the same person.

Entry Element: 22.4-22.11 (33-39)

Once the name has been established, it is time to decide on the order of the components of the name in the heading. The general rule is to follow national usage, unless a person’s preference is known to be different. In most cases the surname is the entry element. Problems occur with compound surnames (Lloyd George) and names with prefixes (if Van Gogh, why not Van Beethoven?). AACR2 lists the commoner national usages; the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA, 1996) publication Names of Persons may be consulted for others.

The section tails off in an entertaining miscellany, including persons who are to be entered under a title of nobility (Lord Byron becomes Byron, George Gordon Byron, baron); under a given name (Leonardo, da Vinci); or under initials etc., or under a phrase: the lottery winner’s friend Mystic Meg’s name should surely have been inverted according to 22.1IB; and the 1920s book Memoirs of a Flapper/by One, is solemnly entered under the heading One.

Additions to Names: 22.12-22.20 (40-43)

In some instances AACR2 calls for additions to names. They may be needed for identification purposes (Francis, ofAssisi, Saint, Moses, Grandma; Elizabeth I, Queen of England; or even Beethoven, Ludwig van (Spirit)). Often though they serve the collocative function, distinguishing names that would otherwise be identical (Smith, John, 1924-; Smith, John, 1837-1896); Murray, Gilbert (Gilbert George Aimé); Murray, Gilbert (Gilbert John). There are also a number of special rules for names in certain languages, which cover a small number of Asiatic languages only. Names of Persons examines a wider range.

References to Personal Name Headings

References generally are used to make different approaches to a heading. In this they differ from added entries, which make different approaches to a work. References are made from a form of name that might reasonably be sought to the form of name that has been chosen as a heading. References therefore should not be made to non-existent headings, and there must be a mechanism (normally a function of the authority file: see Chapter 13) to record under every heading which references have been made to it

Chapter 22 gives some specific instances of the use of references. The conventional symbol x introduces the name from which reference is to be made, thus

Leonardo, da Vinci

x Vinci, Leonardo da

is an instruction to make the reference

Vinci, Leonardo da see Leonardo, da Vinci.

References are treated in full in Chapter 26. See references are made as necessary from different names, from different forms of a name, and from different entry elements of a name. Two examples of each type follow:

Barrett, Elizabeth see Browning, Elizabeth Barrett

Königsberg, Allen Stewart see Allen, Woody

Ovidius Naso, Publius see Ovid

Nanaponika, Thera see Nyanaponika, Thera

Dr Seuss see Seuss, Dr

James, Anne Scott- see Scott-James, Anne

In the case of pseudonyms, see also references are made to link the different headings used for the same person, for example:

Innes, Michael see also Stewart, J.I.M.

Stewart, J.I.M. see also Innes, Michael

A variant is the explanatory reference, typically for contemporary authors appearing under several pseudonyms:

Plaidy, Jean. For this author under other names, see Carr, Philippa, Ford, Elbur, Holt, Victoria, Kellow, Kathleen, Tate, Ellalice

Corporate Bodies

Before rules for headings for corporate bodies are given, AACR2 has a short chapter on geographic names. Geographic names are not used as such, but may constitute, or be added to, a heading for a corporate body. Specifically, they are used:

as the names of governments and communities

to distinguish between corporate bodies with the same name

to add to some corporate names (particularly names of conferences).

They have their own chapter in AACR2 because of their pervasive nature. The chapter is, however, little more than an appendix to Chapter 24 (Corporate bodies) (45-47). The rules are uncomplicated (but note the international emphasis: country is almost always added to the names of places smaller than a country).

AACR2’s definition of a corporate body was given earlier in this chapter: ‘an organization or a group of persons that is identified by a particular name and that acts, or may act, as an entity’. From a cataloguer’s viewpoint, the principal differences between a person and a corporate body are:

Persons are unique and indivisible. A corporate body may have subordinate or related bodies whose names require the parent body’s name for proper identification. (This can include government departments.)

A person who changes their name remains the same person. Change of name in a corporate body normally denotes a change of purpose or scope, so that the body under its new name is a different body from the old.

Establishing the Name of a Corporate Body

Rule 24.1 (43), the General rule - ‘Enter a corporate body directly under the name by which it is commonly identified’ - was quite revolutionary when introduced in 1967. The examples are worth studying by anyone involved with manually searched indexes, since ‘directly’ is rigorously applied and often conflicts with telephone books and other everyday reference tools. Thus Colin Buchanan and Partners files under letter C, not at any inversion of the name under B; the University of Oxford is to be sought under U and not 0; and so on.

The name by which a body is ‘commonly identified’ is to be determined if possible from items issued by the body in its language. When this condition does not apply, reference sources (including works written about the body) are to be used.

The rules for variant names broadly follow personal authors. For the most part they prescribe what most people would intuitively choose:

|

Unesco |

not |

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Society of Friends |

not |

Quakers, or Religious Society of Friends |

Additions, in 24.4 (45), are prescribed for names which do not convey the idea of a corporate body. Study the examples: Bounty (Ship) and Apollo 11 (Spacecraft) help to illustrate the breadth of definition of a corporate body. Ships have a name and may act as an entity - the Bounty’s logbook is a famous example. (Spacecraft, one assumes, qualify only if they are manned?) Rock groups and the like often require this kind of parenthetical qualifier, and one could endlessly argue the toss over whether Spice Girls conveys the idea of a corporate body as opposed to, say, Oasis.

The rule prescribing additions for bodies with identical or similar names takes us firmly into the field of the bibliographic catalogue. In the main, it is place names that are to be added. If the mind balks at some of the detail, such as the presumed documented existence of three different Red lion Hotels in three different British towns all called Newport, it is as well to remember that much of the cataloguing envisaged by these rules can be quite specialized - the local studies departments of public libraries, for example.

Omissions, 24.5, do not require much attention; in the main, they codify commonsense omissions of initial articles, citations of honour, and terms indicating incorporation etc.

There are a number of special rules prescribing additions for specific types of body: governments and conferences are the most important of these. Additions for Governments, 24.6, are needed when governments at different levels share the same name, as with New York city and New York state. In the case of conferences, 24.7 (46), AACR2 comes very close to prescribing a ‘structured’ form of heading. We are instructed to omit from the name any indications of number, frequency or year(s). These are to be tacked on to the end of the heading, together with the date and location of the conference. The resulting headings take the following pattern:

International Congress of Neurovegetative Research (20th: 1990: Tokyo, Japan)

How does one retrieve such a heading? With keyword access all is well; but in manually searched indexes, the slightest error in transcription (‘Congress’ mis-remembered as ‘Conference’, or even the substitution of ‘on’ for ‘of’) can make headings of this type well-nigh irretrievable. Experienced searchers faced with this type of situation will have other search strategies to hand: a keyword search if one is available, or the subject approach, or better still access to Boston Spa Conferences.

Subordinate and Related Bodies

These are to be entered directly under their own name whenever possible, 24.12 (47): that is to say, when the name does not necessarily imply subordination. Thus the Bodleian library belongs to the University of Oxford, but it is to be entered directly under its name, even though the format may be inconsistent with other university libraries.

Bodies to be entered subordinately, 24.13 (48) include:

a body that is subordinate by definition: e.g., Department, Division, Com mittee: provided it cannot be identified without the name of the higher body

a name that is so general that it requires the parent body for proper identification

a name that does not convey the idea of a corporate body

university faculties, institutes, etc., where the name simply denotes a field of study

a name that includes the entire name of the higher or related body.

As always, AACR2R’s examples should be studied carefully.

In many cases with subordinate bodies there is a hierarchy of subordination. Where there are three or more levels of subordination, cataloguers are instructed to omit intermediate elements in the hierarchy unless this might result in ambiguity. This rule had some purpose in manually compiled and searched indexes, in preventing headings from becoming unnecessarily long. However, it necessitates some complex references (as well as being difficult to apply consistently); and in the context of machine retrieval, it has been argued that it would be simpler either to use the subordinate body on its own as a heading, or to set down the complete hierarchy once and for all, allowing each searcher to home in on whichever part of it they wish.

Government Bodies and Officials

Governments form one of the most important categories of corporate body. Governments operate at many levels: international, national, regional, local. Mostly, a government is entered under its conventional name, which is the geographic name of the area governed, 24. Essentially governments are treated in the same way as any other corporate body, and the Concise AACR2 does just that; but because of their complexity the full AACR2 devotes a section, 24.17-24.26, to them.

National governments have three traditional areas of responsibility: the legislature, for which the agency is the country’s legislative body, e.g., Parliament, Congress; the executive, which consists of the government and its various departments, ministries, etc., and also its armed forces; and the judiciary, or courts of law. Governments also have ambassadors and other agencies to represent their interests abroad. Much of the complexity of headings for governments derives from the tendency of modern government to pervade and regulate more and more areas of everyday life. The range of government agencies today is such that AACR’s general rule, 24.17, and default condition is that a body created or controlled by a government is to be entered directly under its name, with a reference from the agency as a subheading of the name of the government, thus:

Heading: |

Arts Council of Great Britain |

Reference: |

Great Britain. Arts Council see Arts Council of Great Britain |

The agencies performing the central functions of government are entered as a subheading of the name of the government according to rule 24.18, which somewhat paradoxically forms an exception to the general rules for governments. The proliferation of government agencies today is such that an official publication is to be assumed not to be concerned with one of the central functions of government. Rule 24.18 lists 11 types of government agencies to be entered subordinately. As a further exception, there are special rules for government officials, legislative bodies, constitutional conventions, courts, the armed forces, embassies and consulates, and delegations to international or intergovernmental bodies - all of which are entered subordinately. Where there are degrees of subordination, the general rules - 24.14, elaborated at 24.19 -apply. The special rules have some exceptions, however: the heading for the US Senate is United States. Congress. Senate and not simply United States. Senate; a similar construction is prescribed for other legislative bodies, and for armed forces.

AACR2 also devotes three pages to special rules for religious bodies and officials - 24.27.

References to Headings for Corporate Bodies

The principles for making references to corporate bodies are similar to those for personal names. The following are some typical instances, covering different names, different forms of a name, and different entry elements:

Deutschland (Bundesrepublik) see Germany (Federal Republic)

Friends, Society of see Society of Friends

International Business Machines Corporation see IBM

Quakers see Society of Friends

Religious Society of Friends see Society of Friends

Roman Catholic Church see Catholic Church

RSPB see Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization see Unesco

Subordinate bodies lead to complications not found with personal names:

University of Oxford. Bodleian Library see Bodleian library

and for more than one degree of subordination:

Great Britain. Department of Energy. Energy Efficiency Office see Great Britain. Energy Efficiency Office

Change of name in corporate bodies can give rise to more insidious complications:

Great Britain. Board of Education

see also

Great Britain. Ministry of Education

Great Britain. Department of Education and Science

Great Britain. Department for Education and Employment

with similar references under the three other bodies. In such cases an explanatory reference is often recommended, giving the dates between which each name applied. Rule 26.3C has some even more complex examples.

Uniform Titles: 25 (51-55)

Uniform titles are filing titles supplied by the cataloguer, and are used optionally. They have two functions:

To bring together entries for different editions, translations etc. of the same work, appearing under different titles.

To provide identification for a work when the title by which it is known differs from the title of the item in hand.

Function (1) is typical of collocative catalogues. It belonged originally to manually searched files: a uniform title such as

Dickens, Charles

[Martin Chuzzlewit] The life and adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit

could be retrieved electronically by keyword access even without the uniform title. Function (2) however is a finding-list function and is valid irrespective of the mode of searching. A person searching for an edition of Swiff s Gulliver’s Travels could conceivably have problems retrieving this without its uniform title:

Swift, Jonathan

[Gulliver’s travels] Travels into several remote nations of the world / by Lemuel Gulliver

and a work such as this:

[Arabian nights] The book of the thousand and one nights

could be completely irretrievable.

There are a number of special categories of works that might carry a uniform title. They include:

Collections: a uniform title may be used to collocate complete or partial collections of an author’s works, where these appear under different titles; for example:

Maugham, W. Somerset

[Selections] The Somerset Maugham pocket book

Specific uniform titles are prescribed for use as appropriate, for example: [Works], [Poems], [Short stories], [Poems. Selections], [Short stories. Spanish. Selections].

Sacred scriptures. Uniform titles for the more logical arrangement and retrieval of the Bible and other sacred scriptures are well established. The method is reminiscent of subject retrieval with its fixed citation order:

Bible. Testament. Book or group of books. Language. Version. Year.

For example:

Bible. N.T. Corinthians. English. Authorized.

Bible. English. Revised Standard. 1959.

Music. Music, especially classical works, often requires a uniform title as the international nature of music publishing often results in editions of works having title pages in a variety of languages. They are best explained by examples:

Handel, George Frideric

[Messiah. Vocal score]

Rossini, Gioacchino

[Barbiere di Siviglia. Largo al factotum]

Schubert, Franz

[Quintets, violins (2), viola, violoncelli (2), D. 956, C major]

Discussion

Citations, Catalogue Entries and Metadata

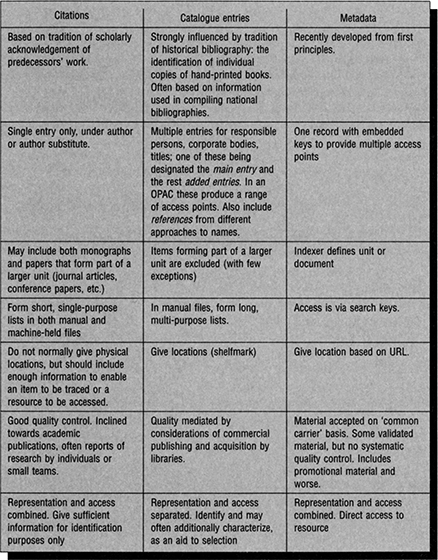

This chapter opened by referring to earlier chapters where document representation was described. AACR2 is unusual in its careful separation of representation (description) and access. While Chapter 3 did not discuss document access as such, it did discuss citations, where the document representation has its own built-in access point. Also, in Chapter 2 we looked at metadata, a mechanism for both representing and accessing networked electronic resources. Citations, catalogues and metadata have evolved through quite different traditions. Figure 9.6 summarizes some points of similarity and contrast.

Direct Versus Collocative in AACR2

Showing the relationship of an item with others is complex and in some respects controversial in the context of cataloguing. A catalogue in its basic finding list function focuses on the individual item. Two works by the same author are clearly related to the extent that they are products of the same brain. Queen Victoria, after meeting the author of Alice in Wonderland, expressed the desire to be given a copy of his next book, and was presented to her disappointment with a mathematical treatise. AACR2 has relaxed the bibliographic unit of authorship to the extent of allowing both Carroll, Lewis and Dodgson, Charles Luttwidge as headings. Within the description, relationships may be shown in many ways. One kind of relationship that must be shown is one that the author considers important enough to incorporate into the title or statement of responsibility: this covers many works of mixed responsibility, 21.8-21.27, as well as those falling under the rule for related works, 21.28. Any edition statement implies a relationship with another edition; any series statement is a clear indication that the item has siblings. The Notes area is a catch-all for relationships which cannot be expressed within the body of the description - that is, which do not appear in the chief source of information. Rule 1.7 has several examples of notes indicating continuations, translations, adaptations, and the like. The danger of this is the implied invitation for cataloguers to turn themselves into literary detectives, and the question to be asked is, does this information add anything to the usefulness of the catalogue? Is the fact that The Second Sex is a translation of Le deuxième sexe something that a person needs to be told in the catalogue, or can they be left to discover it for themselves? If the cataloguer can find the information within the item, then so can the reader.

Figure 9.6 Citations, catalogue entries and metadata

AACR2 maintains an uneasy compromise between the direct and bibliographic functions of catalogues. The various rules that point to either function are as follows.

Rules pointing to a direct catalogue

Access points are to be determined from the chief source of information (21.0B).

The heading for a person is based on the name by which he or she is commonly known, as determined by the chief source of information (22.1).

Persons who have established two or more bibliographic entities under different names may be entered under different names (22.2B).

The heading for a corporate body is based on the name by which it is commonly identified (24.1).

Rules pointing to a collocative catalogue

Parts of a full Description, such as Series (1.6) and edition and history notes (1.7B7) link the description to related works.

Persons known by more than one name (other than a pseudonym) are to be entered under a single uniform heading, which may differ from that appearing in the chief source of information (22.2).

Additions are prescribed to headings for persons in order to distinguish identical names: these may be dates (22.17), fuller forms of the name (22.18) or distinguishing terms (22.19).

Where variant names of a corporate body are found, one of them is chosen as the basis for the heading (24.2-24.3).

Additions are prescribed to names of corporate bodies to distinguish two or more bodies having the same name (24.4[en24.11).

Uniform titles provide ‘the means for bringing together all catalogue entries for a work when various manifestations (e.g. editions, translations) have appeared under various titles’ (25.1).

In practice, there is a greater polarization than is immediately apparent. On the one hand, some national bibliographic agencies routinely make additions to names (dates of birth, expansion of forenames), even where these are not immediately required to distinguish identical headings. (It is cheaper to do this than to amend an existing heading when a conflict does arise.) On the other hand, the accuracy of any given catalogue is only as good as its authority file, and in particular the diligence with which this is applied. Failure to recognize an existing heading, the addition or omission of a distinguishing date, or the slightest variation in spacing or punctuation, will in most retrieval systems result in the same person appearing under more than one heading. Not surprisingly, there is a well-established lobby against the application of any kind of rules to names. While this is mainly to be found among the abstracting houses, it has also been suggested, with increasing plausibility as the technology improves, that it is possible to create working catalogues based on records derived directly from optically scanned title pages - the ultimate negation of the collocative function. In 1953 Lubetzky asked the question, Is this rule necessary? The question of the future may well be, Are any rules necessary?

The Out-of-Dateness of Cataloguing Rules

A set of cataloguing rules, like any other code of practice, depends on there being a well-established set of procedures that can be codified with general agreement. Codes are thus inevitably backward-looking, and liable to be overtaken by events the moment they are published. AA1908 was implicitly designed with printed book catalogues in mind, and was published just at the time when card catalogues were taking over. Both editions of AACR have been similarly afflicted. The MARC record format is built round cataloguing rules governing the production of card catalogues, and was first implemented in 1968, the year after the publication of AACR1. AACR2 and MARC are virtually two sides of the same coin, and AACR2 is essentially a code designed for manually searched indexes with their immensely long, static lists - and was published just as the first OPACs were coming into use. Twenty years on, not only do we still lack a set of rules designed explicitly for machine searchable bibliographic databases, but there is no consensus on the desirability or otherwise of developing AACR2 in that direction. The awful contemplation of having to restructure MARC and amend millions of existing MARC records is a powerful deterrent to radical revision.

There is movement for change, however, and already much groundwork has been done in redefining the principles of AACR according to the entity-relationship model. Other themes can be identified: for example the need to resolve the ‘content versus carrier’ question: whether cataloguing should be based on the item in hand (or on screen), or on the more generalized concept of the work. Whatever the future may hold, AACR2 has without doubt been highly successful both as a set of rules and as an instrument of universal bibliographic control. It is based on clear principles: treating all media equally; the separation of document representation (description) from document access; and Lubetzky’s conditions approach. It is clearly set out, and lucidly written. It is the first truly international code, accepted and applied throughout the world, having been translated into 18 languages and forming the basis for other codes in use today. It is the first code to be hospitable to all types of communication media. It is easy, when censuring it for what it does not do - perhaps may never do - to forget its massive achievement.

Summary

Headings in catalogues are in essence controlled vocabularies applied to classes of one. Even more than the general classification schemes, catalogues are encumbered with the detritus of well over a century of practice, and their rules remain in many respects Byzantine. In understanding the complexities of catalogue rules, an analytical approach, taking each problem a step at a time, yields the best results. The tension between the direct and collocative functions remains as strong as ever, and an understanding of these functions is fundamental to the appreciation of the role of catalogues and of the author approach generally.

References and Further Reading

Baughman, B. and Svenonius, E. (1984) AACR2: main entry free? Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 5 (1), 1–15.

Boll, J. (1990) The future of AACR2 (in the OPAC environment). Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 12 (1), 3–34.

Bryant, E. (1980) Progress in documentation: the catalogue. Journal of Documentation, 36 (2), 133–163.

Buckland, M. K. (1988) Bibliography, library records, and the redefinition of the library catalog. Library Resources and Technical Services, 32 (4), 299–311.

Carpenter, M. and Svenonius, E. (eds) (1986) Foundations of Cataloging: A Sourcebook. Littleton, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Cutter, C. A. (1904) Rules for a Dictionary Catalog, 4th edn. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (and later reprints).

Fattahi, R. (1995) Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules in the online environment a literature review. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 20 (2), 25–50.

Gorman, M. (1978) The Anglo-American Cataloging Rules, second edition. Library Resources and Technical Services, 22 (3), 209–226.

IFLA (1996) Names of Persons: National Usages for Entry in Catalogues, 4th edn. Munich and London: K. G. Saur.

Lubtezky, S. (1953) Cataloging Rules and Principles. Washington, DC: Library of Congress.

Madison, O. M. A. (1992) The role of the name main-entry heading in the online environment. Serials Librarian, 22 (3/4), 371–391.

Maxwell, R. with Maxwell, M. (1997) Maxwell’s Handbook for AACR2R: Explaining and Illustrating the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules and 1993 Amendments. Chicago: American Library Association.

Oddy, P. (1996) Future Libraries, Future Catalogues. London: Library Association.

Piggott, M. (1988) A Topography of Cataloguing: Showing the Most Important Landmarks, Communications and Perilous Places. London: Library Association.

Piggott, M. (1990) The Cataloguer’s Way through AACR2: From Document Receipt to Document Retrieval. London: Library Association.

Shoham, S. and Lazinger, S. S. (1991) The no-main-entry principle and the automated catalog. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly 12 (3/4), 51–67.

Smiraglia, R. P. (ed.) (1992) Origins, Content, and Future of AACR2 Revised. Chicago: American library Association. (Particularly: Gorman, M. After AACR2R: the future of the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, pp. 89–94; also responses, pp. 95–131).

Swanson, E. (1990) Choice and form of access points according to AACR2. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly; 11 (3/4), 35–36

Weihs, J. (ed.) (1998) The Principles and Future ofAACR: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Principles and Future Development of AACR2, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, October 23–25, 1997. Ottawa: Canadian Library Association. For later developments, see the Joint Steering Committee’s Web site: <http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/jsc/index.htm>.

Winke, R. C. (1993) Discarding the main entry in an online cataloging environment. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 16 (1), 53–70.