11

The Internet and its applications

Introduction

Many of the online search services, and online public access catalogues described in the previous chapter may be accessed through the Internet, the WWW or intranets. This chapter focuses on the wide range of other information sources that may be accessed through the Internet, and considers the ways in which documents that are available over the Internet may be created and accessed. At the end of this chapter you will:

understand the nature of the Internet, the WWW and the information resources to which they provide access

be aware of the tools for searching such resources

understand the basics of creating and maintaining a Web site

appreciate the need for structuring of information in the context of subject gateways

be aware of the processes associated with document creation and publication across the WWW

appreciate the challenges for further development and effective exploitation of this type of networked ‘tower of Babel’.

The Internet

The Internet is a collection of interlinked computer networks, or a network of networks. It can connect millions of different computers and the rate of increase in use and in new subscribers is growing on a month-by-month basis. Historically, the Internet was essentially an academic network, but business use is growing, so that it is no longer an élite network for communication between eminent research centres, but also is accessible to small colleges, small businesses and libraries throughout the world. The Internet offers a gateway to a myriad of online databases, library catalogues and collections and software and document archives, in addition to frequently used store-and-forward services, such as UserNet News and e-mail. In addition, the commercial applications of the Internet are becoming significant. Electronic commerce (e-commerce) is of increasing concern to businesses. The main products sold through the Internet are books, CDs and music and software, but the potential is much greater. Sainsbury and Tesco and other leading supermarkets are in the process of major trials of Internet-based home delivery services. Most businesses regard it as important to have a presence on the Internet, in the form of a Web site, since the Internet is becoming an increasingly important means of promotion and visibility.

The terms Internet and World Wide Web tend to be used interchangeably. Strictly they are not the same thing. The Internet is a world-wide network of interlinked computer networks. The Internet provides global connectivity via a mesh of networks based on the transmission control protocol/Internet protocol (TCP/IP) and open systems interconnection (OSI) protocol. Documents are transferred between these networks using one of a variety of Internet transfer protocols, such as file transfer protocol (FTP) or hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP).

The Web comprises those servers linked to the Internet that use HTTP. This means that documents are linked to one another through hyperlinks that are embedded in each document. Users move from one document to the next using hyperlinks links, which are created through a combination of:

an addressing system that allows the location of any object stored on a networked computer to be uniquely identified by a uniform resource locator

mark-up language (HTML) that allows the authors of documents to identify a particular location within their document as the source of links, and to specify the location of the target of those links

a transfer protocol (HTTP) that allows copies of target documents stored on remote servers to be retrieved and displayed

a client program, or Web browser such as Netscape Navigator or Internet Explorer that provides the user with control over the retrieval process and over the links to be activated.

People and organizations create home pages to present their own information or service. A collection of home pages, located on the same server is called a Web site. Access to these pages is via the URL using a browser. These addresses link the user to the host computer and their individual files; these are then displayed on the user’s personal workstation. With the appropriate software, users can read documents, view pictures, listen to sound and retrieve information.

From an indexing perspective, the hyperlinks on the WWW that form the basis of the browsing network are uncontrolled, but humanly assigned index terms (or on occasions other objects, such as images). They are normally terms in the body of the text of the Web page. There is no general control over which terms should be used as hyperlinks, but each hyperlink is individually coded by the creator of the HTML Web page that contains the hyperlink.

A Web browser add-on to a Web client program is an external program that can run individually without the help of the Web client software. Many Web clients allow a link to other software in order to represent the contents of a file for which the Web client software has no built in functionally. A plug-in to a Web client program is almost the same as an add-on, except that this plug-in cannot run on its own. Examples of add-ons are Adobe Acrobat and the portable document format; PDF is often used to distribute documents in computer readable form, giving a high-quality document that is very similar to the original hard copy.

Another concept often encountered in the Internet world is that of the intranet. An intranet is an organization’s internal communication system that uses Internet technology. Intranets use Web browsers and graphical user interfaces. While the Internet provides largely unrestricted access to its contents to almost any member of the public, intranets have strict access controls, often described as firewalls. These firewalls protect corporate Web pages, document databases and other information from external access.

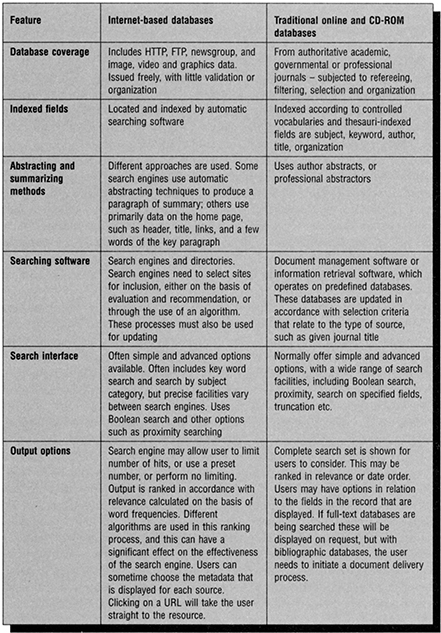

Many of the online search services, and on-line public access catalogues described in the previous chapter may be accessed through the Internet, the WWW or intranets. In addition the Internet offers access to a plethora of other resources. These resources are controlled by their providers and there is no inherent evaluation or validation embedded in their distribution or publication process. In addition, the resources can be volatile. Figure 11.1 summarizes the differences between general Internet resources, and more traditional databases, and the means of accessing such resources. This chapter explores the range of search tools that are available for locating Internet resources, and explores issues associated with the creation and maintenance of a Web site. The creation of subject gateways requires the use of metadata standards, name authority lists, thesauri and classification schemes. The final section on document publication and creation explains the tools that are used in the creation of documents that can be accessed over the Internet.

Searching the Internet

With the vast array of databases and other services available via the Internet it has been important to design interfaces that help users search the information sources and services available on the Internet. Retrieval is recognized to be a significant problem on the Internet, with databases in a wide variety of different formats and numerous different search and retrieval software packages mounted on the different computers and providing access via different interfaces to subsets of the databases. Various print-based similes have been used to describe the situation, one of which is that the current state of the Internet can be likened to a library in which everyone in the community has donated a book and tossed it into the middle of the library floor. Accordingly, a range of tools have been created which help users to locate Internet resources. Some of these rely entirely, or almost entirely, on automatic search and retrieval techniques, while others use human intervention in selection, evaluation and indexing.

Tools that are used for searching the Internet often operate in client/server mode. Server software that allows the user to search the database in a more intuitive way has been set up on many computers on the Internet. The user’s local system runs the equivalent client software that communicates with the server software and gives a homogeneous interface to the data.

Browsers, described above, allow users to navigate between linked documents, but browsing is not an effective means of identifying specific information; this requires a search engine.

Search Engines

A search engine is a retrieval mechanism that performs the basic retrieval task, the acceptance of a query, a comparison of the query with each of the records in a database, and the production of a retrieval set as output The primary application of such search engines is to provide access to the resources that are available on the WWW, and stored on many different servers. A related area of application that is likely to grow in the next few years is the use of search engines as retrieval mechanisms in intranet environments for retrieval of documents from one organization’s collection. Most search services are free, with their financial support coming from advertising revenue and through sales of the underlying technology. They can be located on a remote server on the Web, or located on a local PC or internal network. Increasingly search engines are becoming more than a Web index, and are adding content to their sites, in the form of additional services. Some believe that they are fast becoming information providers or ‘hosts’ in their own right

Since search engines need to provide access to a large and distributed document collection the retrieval process must be efficient This efficiency is achieved by the search engines using metadata to represent Web sites. Typical metadata includes URL, titles, headers, words and first lines. Some search engines also use abstracts and full text.

Each of the records contained in the database maintained by a global Web search service is created automatically by a program called a spider, robot Web wanderer or Web crawler. Each time a spider is run, it is initially issued with the URLs of a small seed set of target Web pages. It retrieves and downloads copies of the targets of those links and then activates every link contained in those pages, and so on, until it has downloaded copies of every single page that it can find. Typical target Web pages are server lists, Whafs new pages, and the most popular sites. The main functions of a spider are the indexing of Web documents, HTML validation, link validation (do links still exist?), what’s new monitoring and mirroring of Web sites.

The content of each page is stored in a record which also contains other fields containing basic metadata such as the title of the document the date on which it was last modified, its size in megabytes and its URL. The values of these attributes are determined automatically from the document Searching on these records is facilitated by the creation of an inverted index. The nature of this index depends on whether searching is by Boolean search or best-match searching (see Chapter 5). The inverted index is stored using compression techniques that reduce to a significant extent the storage capacity that it requires.

The user interface supports the interaction between the user and the system. For query formulation, the Web page presented to the user of a Web search engine typically contains a ‘form’ made up of a text entry box in which the user is invited to enter search terms. Check boxes or menu boxes to allow field limitations or the use of operators may also be featured on the form. Once the query has been formulated, the depression of a button labelled ‘Submit’ or some related term triggers a standard HTTP request to GET a document of a particular URL from the search service’s Web server. The data entered by the user is appended to the URL in the form of a string of characters representing certain parameters and their values, together with a specification of the search program which is to be run, and to which those values should be passed, before the GET request is fulfilled.

Most Web search services use a best-match search process and present search output in order ranked by relevance. Relevance is calculated by the search engine and is based on:

how many of the search terms were found in the document

how often the search terms were found in the document

where in the document the search terms were found (e.g. URL, metatags etc.)

proximity of the terms to one another

rarity of the terms.

Different search engines give different weightings to each of the above elements.

The assumption here is that the more similar a record is to a query, the more likely the document that it represents will be relevant to the user’s information need. It is not unusual to find a very large number of hits; if this is the case, a rule of thumb is to scan the first 50 hits and, if these do not provide useful information, to consider redesigning the search strategy. On occasions it is possible with some search engines to get a completely different set of results on the basis of the same search strategy. This idiosyncrasy arises because some search engines, Alta Vista being a prime example, allocate a set amount of time to each search, and with complex or long searches the results displayed are those found when time has run out, and are not a complete set.

Once the search has been run, the Web server responds to the GET request by sending to the user a Web page for display in place of the original search form, whose content includes the output of the search program. The displays of the retrieval set typically take the form of a list of Web pages representing the records retrieved, ranked in order of their potential relevance to the query and presented a certain number, say, ten at a time; each of these incorporates a hypertext link to the source document presented by the record, and clicking on it will call up the source document This may be accompanied by a statement of how often each of the search terms were found in the whole database.

The information that is displayed for each entry in the results list derives from the data that is used to describe the site in the search engine database and typically includes:

the title of the page

the URL of the page

a description taken from the metatag at the start of the Web page

the relevance ranking of the site as calculated by the search engine

the size of the page or file

a date, which is usually the date that the page was loaded on to the server.

There are a number of different types of search engines. These include directories, subject gateways, meta search tools, and search bots and intelligent agents.

Basic search engines, such as Alta Vista, collect data by sending out programs, known as spiders or robots, on to the Internet to look for new and updated Web pages. Information is brought back to the database. The whole process is automated.

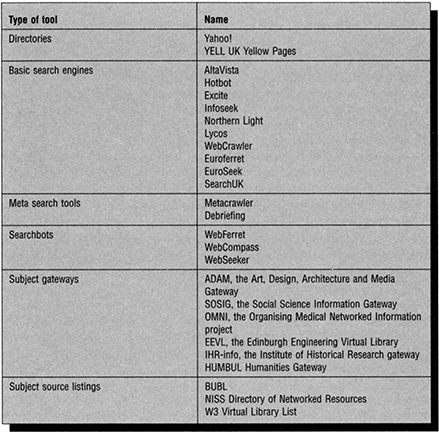

Directories, such as Yahoo! add value through human intervention in the assignment of subject headings to records in databases. In addition, all sites are visited and evaluated prior to inclusion. Web site creators may submit their page for consideration, but inclusion is subject to an evaluation process. Searching is via menus of the added subject headings, or through keyword searching. The maintenance of such directories is a labour-intensive process, which means that the search service is selective in the sites that are included. However, selection reduces the amount of garbage that can often present real problems in searching the Internet. Experiments are under way in the areas of semantic knowledge bases and the use of thesauri to improve search effectiveness. In addition, the users’ ability to assess the relevance of a document depends critically upon the metadata that is displayed about the document in the displays of the retrieved set. Accordingly this is another area of current interest.

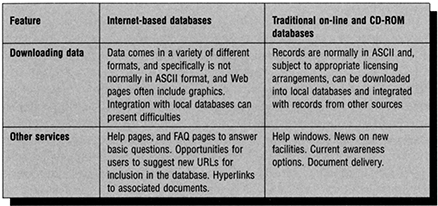

Subject gateways, are similar to directories except that they have a specific subject focus. All resources are evaluated prior to inclusion. Some examples are listed in Figure 11.2. Most of those listed in Figure 11.2 are funded through the UK elib initiative and, in general, represent the work of a group of academic libraries. There are also a number of more specialized gateways produced by libraries or individuals. Subject listings maintain an up-to-date list of these gateways, and can be useful in locating a gateway in a specific subject area. The creation and maintenance of subject gateways is explored in more detail below.

Figure 11.2 Some examples o! Internet search tools

Meta search and all-in-one tools search for words and phrases across a number of search engines at the same time. They then amalgamate results, remove duplicate entries and present a single listing. They are a quick way of searching across several search tools, although they may not support some of the more sophisticated search facilities.

Search bots act like meta search tools, and search many Internet search engines in parallel. They differ from meta search tools, in that they are loaded on the local workstation, rather than operating in client server mode.

Intelligent agents can be used to collect relevant items on the basis of a search profile. Once a search has been performed, the user needs to assign relevance rankings to the items retrieved. The intelligent agent uses this information to modify its search process in its next iteration. Such tools are particularly useful in current awareness searching and other contexts in which the same search needs to be rerun.

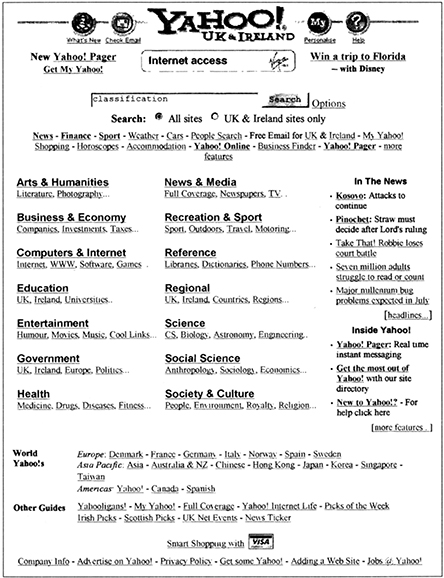

Search engines differ from one another in the following important respects:

Coverage of the database. Some engines only provide access to WWW resources, whereas others provide access to a wide range of Internet resources. Other constraints may relate to the section of the site that is indexed. Yahoo!, for example, indexes only the home page of a site that is listed and not every page.

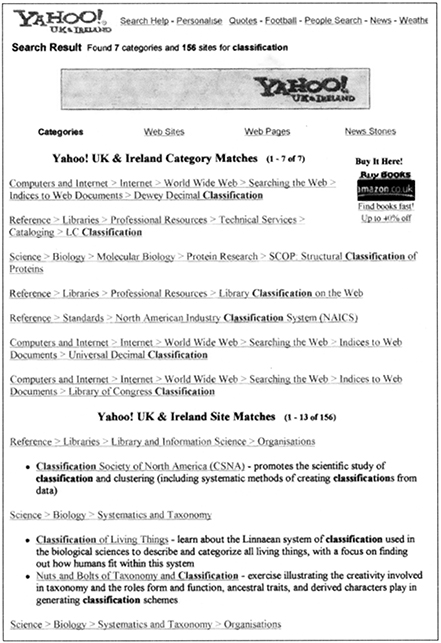

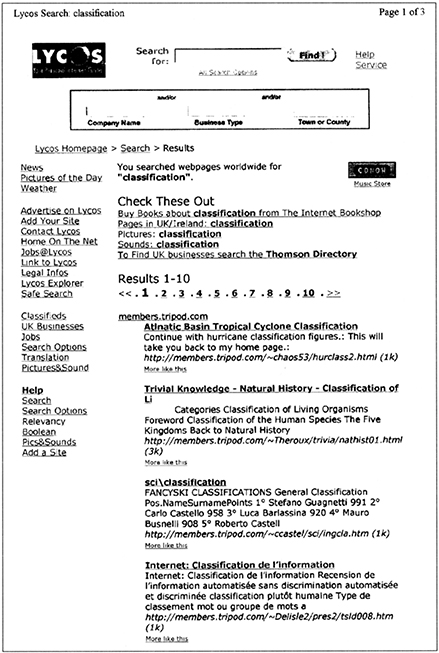

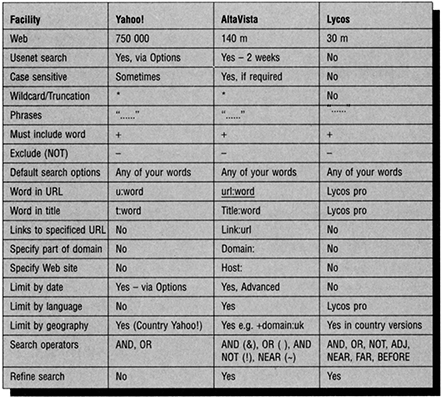

Search facilities and process. Search engines search different parts of HTML documents. Some search only titles and headers, and not the full text of the HTML document. The range of search facilities also varies. Some search engines offer only basic keyword searching, but others offer Boolean searching and, even, proximity searching. Figures 11.3, 11.4 and 11.5 give some examples of the search facilities offered by search engines.

Results list. Some engines display a simple list of resources, while others include the context of the hit, weighted results and options to link to similar pages.

Versions of search tool. Many search tools have different versions for different countries. Yahoo!, for example, has a common main database, but the interface and headings are in the local language, and the results listings are displayed with sites based in that country region at the top. Current news stories and events also reflect local interests.

An awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of the different search engines is important in searching the Internet for resources (Figure 11.6). If a library is designing a Web site, it is important to be aware of the search engines that users may use in accessing that Web site.

Creating and Maintaining a Web Site

Most businesses and other organizations will use a Web site to increase their visibility in cyberspace. The Web is increasingly being seen as an opportunity for communication with customers and potential customers, suppliers and staff. The range of applications of a Web site for a typical organization may include:

Providing basic information about the organization, such as product and services available, hours of availability, contact people, addresses and policies. There is an opportunity to make such information more interesting than through other media, through the inclusion of pictures of staff, a short sound file or direct e-mail links which allow users to send messages.

Figure 11.3 Yahoo! search page: search specification

Figure 11.4 Yahoo! search page: search results

Figure 11.5 Search results from Lycos

Figure 11.6 Comparing search facilities in search tools

New ways through which customers can access organizational facilities and services. Examples for libraries include:

- book request forms that can be completed by users, and then converted into catalogue data

- remote access to catalogues

- improved OPAC search interfaces

- showcase to library resources, such as library tours, or a video of story-time

- new information services, such as a home page linked to a collection of electronic texts, databases and other Internet resources; such access can be designed for specific user groups, such as children, or the housebound

- access to the resources of the online search services.

Interactive home pages, offering facilities such as:

- fill in forms used for feedback and services

- requests for purchases

- questions concerning services.

Linking customers to remote information, and connecting to information resources around the world. These resources may be other sites that the organization thinks might be useful or, alternatively, the sites of related organizations whose products and services they may wish to promote. Hot lists and bookmark files of frequently used resources for support in answering frequently asked questions, may be provided.

Staff development. Offering a WWW service allows staff the opportunity to keep involved in developments in this field, and to be aware of what related organizations are doing in the areas of e-commerce, and e-communication.

Communication with suppliers - The Internet can provide access catalogues of suppliers’ products, and mechanisms for placing orders.

Policy and practice documents, and other internal documents can be distributed to geographically scattered sites in order to keep the various members of staff in an organization aware of developments.

Document delivery. Electronic documents are one of the main products that can be provided digitally. The use of the networked pubic access catalogues of other libraries, and the online search services, coupled with document delivery services is an increasingly important avenue for document delivery.

The creation and maintenance of a Web site needs continuing commitment. Web sites need to be professionally designed and regularly updated if they are to portray a positive message about the organization. A Web site is a shop window for an organization and its services. A Web site needs to be managed in much the same way as any other promotional venture or service. Clear objectives need to be identified at the beginning of a project to create a Web site; these will determine the content and design of the site. In a burst of enthusiasm it is easy to view a Web site as a one-off project. For continued effectiveness the resources need to be available for updating, evaluation and maintenance. Some of the issues that need to be considered include:

Objective: the creation of a Web site must start with the identification of the objectives of that Web site. Standard promotional questions need to be asked and answered: Who is the audience? What is the message? Which is the most appropriate form in which to convey the message? How can the likelihood that the message will be seen or heard be maximized? If the Web site also has a purpose in supplying services, or in offering access to other information, the nature and scope of these facilities need to be determined and agreed. In large organizations it may be necessary to coordinate the creation of a number of Web sites, and to agree the distinct objectives of each.

Staff ownership: staff should identify with and be aware of the site and its intended objectives. This can most effectively be achieved by keeping staff involved in the development of the site, and encouraging them to visit the site from time to time. Staff involvement is essential because they need to be aware of the messages that are being conveyed to others and, in particular to customers, and also, if they are in contact with customers, when to refer customers to the Web site services. In addition, staff input of a variety of different types will be needed in order to be confident that the information provided on the Web site is current. Staff may be involved in updating basic information about the organization’s activities, or alternatively they may be responsible for other aspects of the content of the Web site, such as the maintenance of links to other related Web sites.

Content information may need to be drawn from sources across the organization; these sources must be identified. Any new content will need to be designed. Remote content needs to be located, and evaluated prior to selection. Further discussion of the evaluation of content for inclusion in Web sites follows in the section on setting up a gateway.

Presentation is concerned with structure and style of the Web site. This includes the design of the individual pages, but also the underlying template and design that provides a standard for all pages. Consistency in this area can be a particular challenge for large multinational organizations, where there may be a number of different Web sites loaded by different parts of the organization. A corporate image needs to be established and used throughout In this context it is important to remember that the Web facilitates global communication. The Web space structure, which is determined by the way in which pages are linked together, is also an important element in design.

Promotion is concerned with attracting visitors to the site. As with any other product or service, the work does not stop when the product is completed. A Web site needs promotion. This can be achieved through workshops, posters and over the WWW. links with other sites, and inclusion in search engines are much coveted for promotional purposes.

Evaluation is concerned with monitoring whether the Web site is achieving its objectives. The number of visits to the site is one measure of success, but more searching evaluation can be achieved through user evaluation, and whether interest or business is being generated as a result of the visit. Regular communication with users through electronic suggestion boxes and other interactive devices provides useful information for evaluation.

Maintenance can be a major task. Information needs to be updated, and, as the information is updated, links between pages must be reviewed. A new corporate image or design requires a complete overhaul of the design of all pages in the Web site.

Establishing a Subject Gateway

A number of organizations, including groups of academic libraries, have sought to establish gateways to Internet resources, or to embed some guidance on appropriate resources in a home page. Some examples of such gateways are listed in Figure 11.2. These projects are a recognition that, although there is a wealth of information available through the Internet, browsers and search engines are not always effective in identifying the most important sources. This is largely because such tools are, at best, limited in the extent to which they seek to evaluate sources. Internet resources:

include a large amount of junk

have grown rapidly, which leads to significant changes in the resources available on a daily basis.

include resources which disappear, or cease to be of use because they are not updated.

A key issue for users, and for the creators of gateways that are intended to help users in navigating Internet resources, is quality assurance and, specifically, quality assurance in a shifting morass of resources. There is no standard or authority associated with publishing on the Web. Publishing standards that have been well tested and established in print publishing do not yet apply to the Internet. Internet resources are not subject to the type of evaluation, refereeing, reviewing and editing processes associated with print publishing. In other words, some of the stages in the 7 Rs model (Figure 1.1) are bypassed. The onus for evaluation lies with the user, or with the information professional who seeks to create a subject gateway. The key issues in quality assurance are authority, accuracy, appropriateness and accessibility:

Authority is often evaluated on the basis of the author, the publisher, or the originating institution for a given resource. Problems arise when one of these cannot be identified, or when it is difficult to assess the authority of the agent in this context. This assessment of authority requires subject knowledge and an awareness of the authority and reputation of originators of information.

Accuracy is more difficult to assess in the absence of reviewing, assessing and editing. It is possible to check superficial factors, such as spelling, typography and grammatical errors. Evaluation of the accuracy of the content depends on the evaluator’s subject knowledge.

Appropriateness, or the interests of the anticipated audience. Key aspects in determining appropriateness are subject and currency. A gateway may define its boundaries in terms of subject coverage, or may be seeking to provide a service for, say, a specific academic community with relatively wide subject interest Currency can be determined by examining the dates of the last update in different sections of a resource; it is important to check more than just the home page. Different levels of currency will be required from different types of source.

Accessibility is determined by file format, storage location, and whether users need to be subscribers, or make other payments for access to the information.

The establishment of a gateway may be viewed as the creation and maintenance of an electronic library collection. Processes associated with the maintenance of such a gateway include selection, creation of metadata, authority lists for names, use of controlled subject terms, classification, and search facilities and interfaces.

Selection of items for inclusion. This is one of the key challenges, partly because of the issues associated with the evaluation of resources that have been outlined above. In addition, there are no formal selection tools, in the conventional sense. Resources need to be identified through search engines and browsers. Intelligent agents can be used to check resources for new information and new sites, so that the gateway can be kept up to date.

Metadata. It is necessary to establish a method of describing resources. Reference to standards such as those embedded in AACR, MARC and the Dublin Core are useful here (see Chapter 2). Specific decisions are concerned with:

- Whether to use pure metadata from within the HTML of a given resource, as the basis for the record

- What resource description format to adopt

- Establishing an appropriate level of granularity in the resource description and handling the relationships between resources.

Authority lists for names are important if searching is likely to be performed on names. For example, the ADAM gateway, which covers Art, Design, Architecture and Media, uses the Union List of Artists’Names, from the Getty Information Institute.

Controlled subject terms are often used as the basis for subject searching within the gateway. Gateway designers may make use of an existing thesaurus, such as Art and Architecture Thesaurus, but since most special thesauri have been developed for specific purposes, there are likely to be subject areas covered by a gateway for which there is either no thesaurus, or the existing thesaurus needs further development. Some in-house thesauri development may be necessary.

Classification is central to the provision of a browsing facility within the gateway’s database. On the other hand, the one-locument-one-place mentality that derives from an environment in which classification was used to guide the location of books on shelves is less relevant. Faceted classification would allow multiple approaches to one source. The internationally recognized standards, such as DDC, UDC and LCC are not always appropriate in gateways with a specific subject orientation. Again, special classification schemes may assist in some applications, but many gateway developers may need to design and maintain a classification scheme that meets their particular purposes.

Search facilities and interfaces are determined by the search software that is used to create the gateway. It is desirable for there to be both simple and advanced interfaces. A useful range of search facilities includes: Boolean logic, searching on specific fields, stemming or truncation, proximity searching and relevance ranking. The integration of thesauri supports the expansion of searches. Other useful facilities are the ability to handle natural-language enquiries, duplicate checking and report-generating tools.

Evaluation and updating. The effectiveness of the gateway needs to be evaluated, with feedback from users. In addition, the sources that are included in the gateway, as well as, from time to time, the design of the gateway will need revision.

How to Guide: Questions for Use in the Evaluation of Internet Resources

What is the intended audience? Is this academic, business, professional or popular?

What is the frequency of update? Is there any information on updating?

What is the affiliated institution?

What is the resource developer’s expertise? Is there an ‘about’ section that describes the author/creator?

What is the relationship between resources and other resources on the same topic? Are there any links or references to these related resources?

Are there any reviews or evaluations of the site? What do these say?

Is any permission needed for access, and are any charges made for access?

Document Publishing on the Web

Document publishing systems are systems that support the creation, storage and subsequent retrieval and dissemination of documents and/or document representations or metadata. They are widely used in information retrieval applications and, in particular, are important in supporting the publication of documents on CD-ROM or the Web. The documents that such systems manage may be in any medium, including text, graphics, sound, still or moving images, video, or any mixture of these, in the form of a multimedia document. Although there are increasing opportunities for multimedia document creation, the volume of text-based information is increasing at an alarming rate, with a great diversity of form. This ranges from the relatively unstructured memo, letter or journal article, to the more formally structured report, directory or book. Such text-based documents were previously managed through the earlier generations of document publishing and management systems, then described as text management systems, or text retrieval systems. Text management systems were distinguished from other database management software by a set of characteristics that supported the effective management of text-based applications. These characteristics are still applicable to document publishing and management systems:

the ability to handle variable-length fields and the expectation that many of the fields in the records will be of variable length

access to records is usually through an inverted file of index keys or words from the text of the records on the database

a range of retrieval facilities that support retrieval based on words in records; these are necessary to accommodate the fact that there is limited control over the form in which the search key might appear in the record

emphasis on the management of one or more distinct databases, since the ability to draw data from a number of related databases is not central to the application

relatively fixed applications which require limited programming or systems development facilities.

Large publishers make use of such software in the distribution of a wide range of electronic documents, such as electronic journals and books. In addition, corporate publishing across a corporate intranet is an important application of such systems.

What is the difference between Internet document publishing products and Internet search engines such as Yahoo! and Lycos? The major issue is that Yahoo! and Lycos work on repositories of HTML documents. This gives rise to two problems. First, HTML indexing and retrieval tools have limitations. Second, in many organizations considerable information exists in documents that are not HTML structured, such as word-processed documents and spreadsheets. If these repositories are large it may not be feasible to convert them to HTML documents or, if they are changing, it may not be desirable to manage an ongoing conversion process. In such cases, Yahoo! and Lycos cannot index or search the documents. Internet document publishing products support the indexing of unstructured documents, and provide users with the full-text searching capabilities of those indices. The original document format can be directly searched and made available on the Internet through an HTML search form. These capabilities facilitate publishing internally generated documents for either Internet or intranet use.

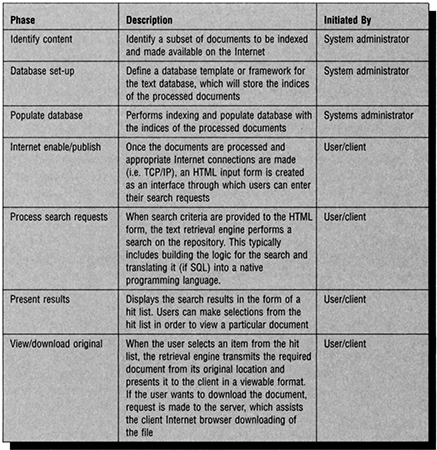

The Publication Process

In order to appreciate the features that are necessary in a document publishing system, it is useful to review the nature of and steps in the electronic publication process. The stages in the process that is associated with making documents available in electronic form, via the Internet or intranet, are represented in Figure 11.7. The stages in the first column of Figure 11.7 are also applicable to publication on CD-ROM. In such applications, the fourth stage becomes publication on CD-ROM. This then needs to be followed by a stage in which the CD-ROM is mounted in a workstation or, for multiple users, a server.

The stages in Figure 11.7 can be divided into two groups:

those executed by the systems designer and document creator

those executed by the document user.

The first four stages are associated with the creation and preparation of the electronic document, or document publishing. The final three stages are concerned with document retrieval. Each of these stages is described briefly.

First, the systems creator will design an appropriate database environment and set up dynamic search and index support tools such as thesauri. Next, documents are entered and tagged, and converted into appropriate formats, often described as populating the database. Such database creation includes indexing. The database or document will then be uncompressed and mastered for delivery in whichever format is appropriate. This may include Internet, CD-ROM, LAN or WAN. Next the user takes over and submits search requests, which are then processed by the software. This results in the display of a results list, from which the user selects one or more documents to view and/or download.

The key issues that a document publishing system needs to address to support effective publication and retrieval are:

the integration of mixed computing platforms in order to avoid disenfran-chisement of some users

data entry and document creation

control over documents once they have been published, including issues associated with security (including control of access) and updating

effective access and retrieval whenever documents are required.

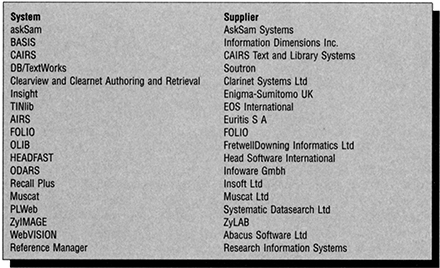

Figure 11.8 lists some document management and publishing systems, together with their suppliers. Contact addresses are not given, since all of these suppliers can be accessed through the Web, using the name of the system supplier as a search key.

Figura 11.7 Phases of the Internet document management and publishing process

Document publishing systems need a range of document creation features, such as:

visual desktops in which documents can be easily arranged for chapter ordering

book catalogues which manage groups of documents

ease of access to creation formats, such as word processing, tables, charts and graphics

advanced tools to support the creation of graphics and images

Figure 11.8 Some document management and publishing systems

version control - to manage document versions throughout the life cycle

access control - to allow different types of access to documents, as well as to implement information security policies for secure document access

tracking - to track document access and change, creating its history to support audit requirements

templates - for defining standard document types, and behaviour and establishing consistent application properties.

The most sophisticated of these packages have an object-oriented architecture. Group-working is supported by view-only facilities, coupled with annotation. Support for multiple languages may also be available, and special features that support the creation of SGML documents. Some of these manage document objects, rather than complete documents. The really large systems need to be capable of operating on multiple servers to serve vast user communities and store vast databases. This requires very large database (VLDB) capability to allow an index to be split physically across several files.

Once the document has been created, questions of use and retrieval arise. In this context the range of information retrieval facilities is important. The retrieval facilities associated with a document publishing system are central to the effective operation of the system. With increasing connectivity, many more users need sophisticated search facilities as they seek to navigate their way through vast quantities of knowledge. Accordingly, more and more of the search facilities that were once unique to document or text management systems are now to be found in the search engines on the Internet, and on library public access systems. Indexing facilities that are especially appropriate in document publishing applications include:

indexing on any field or part of a structured or unstructured document

combinations of automatic indexing, tagged indexing (terms manually selected from text), manual keyword indexing and relational indexing.

Thesaurus construction and maintenance facilities are important and may, for instance, allow the automatic posting of preferred and macro (generic group) terms. Hyperlinks are useful in moving between documents. In a multimedia database, these hypertext links may be pictures, images, spreadsheets and word-processed documents. Other new facilities include ‘note search’ which allows the user to collect selected terms from the output and to use these as a basis for another search if required.

Interface design is also important in effective searching. Most document publishing systems offer GUIs. The use of GUIs has facilitated search strategy editing, recall of earlier search sets, browsing, and the selection and highlighting of relevant documents for later printing or downloading to a personal database. Some systems offer different interfaces for different categories of user, such as expert or novice modes. Multilingual interfaces are a feature of a few systems.

Security is important in any multi-user database environment. The first level of security is concerned with database security. Features such as automatic recovery subsequent to a system failure are important in maintaining the integrity of the database. Access to the database is another aspect of data security. The better systems offer selected access, according to user group, to specified databases, specified documents or records or specified fields. Thus the early definition of document types and attributes is an important device in determining the document views that individual users have of the database. Some users may have read-only access whereas others may be allowed to change the data. Important categories of user might be producer, consumer and administrator. The consumer may only have access to the author and title, the producer may have access also to date, category and abstract, and the administrator may also have access to version and security. The chief security measures offered are passwords and user identification numbers. Security login is useful to report any attempts to breach security. Data encryption is a feature in some document publishing systems.

Special issues that need to be considered when publishing databases over the Internet include:

Access - ensuring that access to the database is stable, but also that users only have access to the files on the server to which they should have access; security must be available for confidential information such as staffing or financial records. Search speed is also crucial; this requires a sufficiently powerful file server.

Database quality and maintenance, including appropriate indexing, needs just as much attention in the Internet environment as in other contexts.

Support - often in the form of online help, but possibly also accompanied by printed documentation. A telephone or e-mail contact point for when things go wrong is often necessary. Also communication with users about new developments is important.

Marketing - databases need to be promoted. Channels include electronic mailing lists and bulletin boards. Other channels such as press releases and receptions still remain important, as are any other contacts with key user groups, such as those at exhibitions. The database also needs to be included in database directories and Internet resources guides. Demonstration discs are valuable.

Further Developments

As more and more organizations recognize the value of effective management of their electronic document collections, the role of document publishing systems will become ever more significant. It is likely that a significant number of these applications will be supported by intranet technology, because this offers the immense attraction of platform independence. Issues that are likely to be significant in the future for document publishing include:

Workgroup publishing - suppliers are beginning to revisit the document creation aspect of document management and to incorporate features that support team-based document creation. As the demand to create more documents in multimedia format grows, so the facilities for group work publishing will need to become more sophisticated.

Increased use of hybrid publication, including the use of CD-ROM/Web. Features necessary to support integration of access to data in different formats will need to be further developed. This includes indexing facilities that can provide access to data stored in these different formats.

Increasing globalization, with applications supporting organizations operating across several countries. The need to manage documents in multiple languages is becoming more pressing.

Closer integration of document publishing and document management facilities in order to create a seamless process of document assembly, management, retrieval, distribution and publication. For some products this will be linked to increased sophistication in their facilities for data entry and document creation.

Closer integration with Web server technology in order to provide Web opportunities that offer seamless access to information. For example, the BASIS Web server gateway is fully integrated with Microsoft Internet Server (IIS) and Netscape Enterprise Server.

Internet and intranet technology offer platforms for document publishing. Document publishing systems already offer important opportunities for electronic publication; it is likely that the number and type of applications supported by these systems will escalate over the next few years.

Challenges for the Internet

Projections of the growth in the number of Internet servers and users accessing Internet resources are available from numerous sources, and change too rapidly to be encapsulated in a book; accordingly, none of these are reproduced here! Nevertheless, the Internet has the potential to realize the final stage of the exponential curve that was embedded in the speculations of writers on the information explosion earlier in the twentieth century. This in itself will pose yet more problems for information management but, in the mean time, there are a number of other problems associated with the exchange of information over the Internet that need to be addressed. Some of these are less pressing if the Internet is viewed largely as a tool for a community of IT enthusiasts and as a means for communication between individuals, but now that commercial applications are becoming significant they will need to be addressed. The issues are:

The World Wide Wait’. One of the most annoying features of the Internet is the speed with which Web pages are delivered to a screen. The graphics embedded in many pages are demanding of transmission capacity and there are a number of servers and clients that suffer from relatively slow telecommunications links. Delays can be further aggravated by high traffic on some sections of the Internet. This will get worse rather than better as the volume of traffic increases, unless higher capacity telecommunications links are available across more elements of the networks that comprise the Internet, and/or improved data compression algorithms allow more data to be transmitted through the same bandwidth.

Security and ownership. Issues of copyright and intellectual property are of particular concern to the information industry, since issues of ownership are at the heart of rights, responsibilities and who has the authority to make commercial arrangements associated with information. These must be addressed through a mixture of legislation that is relevant across an international network (and this is a true challenge in itself), practice, licences and the agreements. However, in addition, to be able to conduct commerce on the Internet, the ability to keep monetary and other propriety information (such as order information) secure as it passes across the Internet, and the need to authenticate the status and identity of the sender, is crucial for effective commercial transactions.

Structure. Users cannot locate the information or the site that they want on the Internet unless they are searching with a specific address, and addresses change. Even the most hardened of technocrats, have been heard to rehearse the wonders of Dewey and other classification schemes. As discussed above, some of the search engines offer evaluation, classification and indexing of Internet resources. The role that search engines play in providing access to Internet resources will evolve over the next few years. Search engines will be viewed as increasingly central in determining which sites users visit; as consumer guides they have the potential to be very powerful. In addition, a greater number of search engines will be necessary to meet the needs of different client groups. An important element in the professional development of information managers will be current awareness in respect of the scope and features of the search engines.

Summary

The Internet and the World Wide Web have changed the landscape of information retrieval. Many of the online search services can be accessed through the Web, and a plethora of other information resources are available through this channel. Although browsers are useful in allowing users to move between documents in searching, search engines are necessary if searchers are to locate specific information There are a number of different types of search engines, including basic search engines, directories, subject gateways, meta search tools and search bots. Search results differ between different search engines. Many organizations create their own Web site in order to enhance their visibility in cyberspace. Other organizations, including groups of academic libraries, have sought to establish gateways to Internet resources. Information managers will not only be involved with the identification of information on the Web, but may also have responsibility for document publishing. Document publishing systems support the creation, storage, and subsequent retrieval and dissemination of documents and document representations or metadata.. Key challenges for the future of the Internet concern the World Wide Wait’, security and ownership, and the structuring of knowledge.

Further Reading

There are a wide range of sources on the Internet and intranet, in both print and electronic form. This is a small sample of such resources that either offer practical advice, or describe case study experiences that might also offer guidance to others embarking on similar projects.

Anonymous (1996) CD-ROM indexing/authoring systems Digital Publishing Techniques, 1 (12), 12–16.

Ashford, J. A. and Willet, P. (1989) Text Retrieval and Document Databases, Bromley, Chartwell Bratt.

Biddiscombe, R., Knowles, K., Upton, J. and Wilson, K. (1997) Developing a Web library guide for an academic library: problems, solutions and future possibilities. Program, 31 (1), 59–74.

Blakeman, K. (1997) Intelligent search agents: search tools of the future? Business Information Searcher; 7 (1), 16–18.

Blakeman, K. (1998) Search Strategies for the Internet: How to Identify Essential Resources More Effectively. Caversham: RBA Information Services.

Blinko, B. B. (1996) Academic staff, students and the Internet: the experience at the University of Westminster. Electronic Library; 14 (2), 111–116.

Boyle, J. (1997) A blueprint for managing documents. Byte, 22 (5), May, 75–76, 78, 80.

Bradley, P. (1997) Going online, CD-ROM and the Internet, 10th edn. London: Aslib.

Bradshaw, R. (1997) Introducing ADAM: a gateway to Internet resources in Art, Design, Architecture and Media. Program, 31 (3), July, 251–267.

Branse, Y. et al. (1996) Libraries on the Web. Electronic Library; 14 (2), 117–121.

Chowdhury, G. G. (1999) The Internet and information retrieval research: a brief review. Journal of Documentation, 55 (2), 209–225.

Clarke, S. J. and Willett, P. (1997) Estimating the recall performance of Web search engines. Aslib Proceedings, 49 (7), 184–189.

Cox, J. (1995) Publishing databases on the Internet. Managing Information, 2 (4), April, 30–32.

Cunningham, S. (1995) Electronic publishing on CD-ROM. In International Conference on Digital Media and Electronic Publishing, Weetwood Hall Conference Centre, Leeds, December 1994. London: British Computer Society.

Curie, D. (1997) Downloading data from the Web: you are not in ASCII any more. Online, 21 (4), 51–58.

Davenport, E., Proctor, R. and Goldenberg, (1997) A distributed expertise: remote reference service on a metropolitan area network. Electronic Library; 15 (4) August, 271–278.

Davies, R. (1996) The Internet as a tool for Asian libraries. Asian Libraries, 5 (1), 43–52.

Dawson, A. (1997) The Internet for Library and Information Professionals, 2nd edn. London: Library Association.

Dong, X. and Su, L. T. (1997) Search engines on the World Wide Web and information retrieval from the Internet: a review and evaluation. On-line and CD-ROM Review, 21 (2), 67–81.

Ellis, D., Ford, N. and Furner, J. (1998) In search of the unknown user: indexing, hypertext and the World Wide Web. Journal of Documentation, 54 (1), 28–47.

Falk, H. (1996) Working the Web. Electronic Library, 14 (5), October, 453–469.

Falk, H. (1997) World Wide Web search and retrieval. Electronic Library; 15 (1), 49–55.

Garlock, K. L. and Piontek, S. (1996) Building the Service Based Library Website; a Step-by-Step Guide to Design and Options. Chicago and London: ALA.

Hamilton, F. J. (1998) Document management: getting better or just complicated? Information Management Report, April, 13–16.

Harrison, S. (1997) NHSWeb: a health intranet. Aslib Proceedings, 49 (2) February, 36–37.

Heery, R. (1996) Review of metadata formats. Program, 30 (4), 345–373.

Helm, P. (1997) Hewlett Packard and the intranet - case study and alliances. Aslib Proceedings, 49 (2), February, 32–35.

Hitchcock, S., Carr, L. and Hall, W. (1997) Web journals publishing: a UK perspective. Serials, 10 (3), 285–299.

Jasco, P. (1996) The Internet as a CD-ROM alternative. Information Today, 13 (3), 29–31.

Jasco, P. (1996) Who’s doing what in the CD-ROM publishing realm. Computers in Libraries, 16 (9), 55–56.

Jeffcoate, G. (1996) Gabriel: gateway to European national libraries. Program, 30 (3), 229–238.

Kalin, S. and Wright, C. (1994) Internexus: a partnership for Internet instruction. In R. Kinder (ed), Libraries on the Internet: Impact on Reference Services, pp. 29–41. New York: Haworth Press.

Kimberley, R. (1986) Integrating Text with Non-Text [En] a Picture Is Worth IK Words: Proceedings of the Institute of Information Scientists Text Retrieval ‘85 Conference, London, Taylor-Graham.

Kimberley, R. (ed.) (1990) Text Retrieval: A Directory of Software, 3rd edn. Aldershot: Gower.

Kimberley, R., Hamilton, C. D. and Smith, C. H. (eds) (1985) Text Retrieval in Context: Proceedings of the Institute of Information Scientists Text Retrieval *84 Conference, London, Taylor-Graham.

MacLeod, R. and Kerr, L. (1997) EEVL: past, present and future. Electronic Library, 15 (4), August, 279–286.

Marcoux, Y. and Sevigny, M. (1997) Why SGML? Why Now? Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48 (7), 584–592.

McMahon, K. (1995) Using the BUBL information service as an Internet reference resource. Managing Information, 2 (4), 33–35.

McMurdo, G. (1995) How the Internet was indexed. Journal of Information Science, 21 (6), 479–489.

Merchant, B. and Winters, N. (1997) Small libraries on the Internet. Library Technology, 2 (4), August, 78–79.

Morrel, P. (1997) Building intranet-based information systems for international companies etc. Aslib Proceedings, 49 (2), February, 27–31.

Nieuwenhuysen, P. and Vanouplines, P. (1997) Libraries and the World Wide Web. Electronic Library, 15 (2), April, 79–81.

Notess, G. R. (1997) Internet search techniques and strategies. Online, 21 (4), 63–66.

Pal, A., Ring, K. and Downes, V. (1996) Intranets for Business Applications. London: Ovum Reports.

Poutler, A. (1997) The design of the World Wide Web search engines: a critical review. Program, 31 (2) 131–145.

Pritchard, J. A. T. (1998) Developments in document management systems. Information Management Report, March, 15–18.

Rowlands, I. (ed.) (1987) Text Retrieval: An Introduction. London: Taylor-Graham.

Rowley, J. (1996) Retailing and shopping on the Internet, Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 6 (1), 81–91.

Rusch-Feja, D. (1997) Subject oriented collection of information resources from the Internet, Libri, 47 (1), 1–24.

Still, J. (ed.) (1994) The Internet Library: Case Studies of Library Internet Management and Use. Westport, CT: Mecklermedia.

Storey, T. and Dalrymple, T. (1996) One the Web with OCLC FirstSearch and NetFirst OCLC Newsletter; (220), 26–29.

Tedd, L. A. (1995) An introduction to sharing resources via the Internet in academic libraries and information centres in Europe. Program, 29 (1), January, 43–61.

Tegenbos, J. and Nieuwenhuysen, P.. (1997) My kingdom for an agent? Evaluation of Autonomy, an intelligent search agent for the Internet. Online and CD-ROM Review, 21 (3), 139–148.

Tseng, G., Poulter, A. and Sargent, G. (1997) The Library and Information Professional’s Guide to the World Wide Web. London: Library Association

Watson, J. (1996) Evaluating Internet text retrieval products. Document World, May-June, 3.

Willet, P. (ed.) (1988), Document Retrieval Systems. London: Taylor-Graham for IIS (The Foundations of Information Science, Vol. 3).

Winship, I. and McNab, A. (1996) The Student’s Guide to the Internet. London: Library Association.

Woodward, J. (1996) Cataloguing and classifying information resources on the Internet Annual Review of Information Science and Technology; 31, 189–220.

Yip, K. E. (1997) Selecting internet resources: experience at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) library. Electronic Library, 15 (2) April, 91–98.