10

System contexts for knowledge organization

Introduction

This chapter introduces the range of different types of systems or technologies in which the approaches to knowledge organization, which have been explored in the previous few chapters, are employed. All such systems offer access to databases. Some of these databases are bibliographic, while others are document databases. Systems, such as the online search services, the Internet and online public access catalogues offer access to a range of documents and databases of different types. At the end of this chapter you will:

be familiar with the wide range of different contexts in which knowledge organization and information retrieval is important

understand the nature of and the facilities offered by the online search services

be aware of the role that CD-ROM plays in access to information

understand the nature and role of online public access catalogues.

Public Access Systems

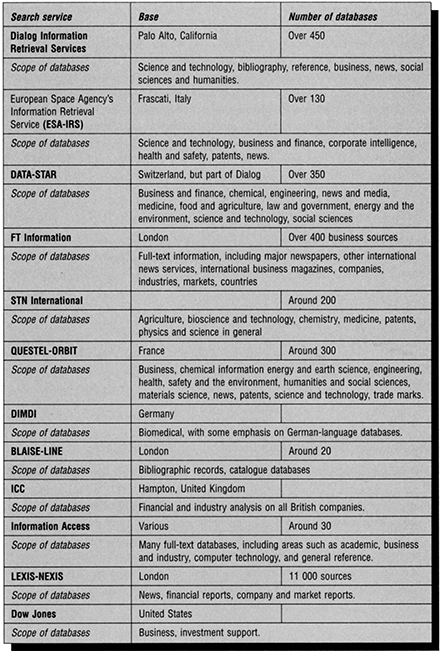

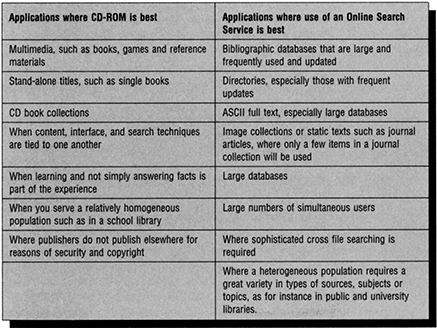

This chapter reviews a number of types of systems that are available to support users in accessing information. All of these systems can be described as public access systems. Online search services offer access to a collection of databases and documents. CD-ROM is essentially a different type of distribution media for information products. Databases and documents can be distributed to consumer markets on CD-ROM, or alternatively, CD-ROM databases can be networked within an organization or library. Online public access catalogues are a unique type of system, which developed from the library catalogue function of providing access to the resources in a library, but have subsequently taken on a range of other functions. Another increasingly important public access system is the Internet and the World Wide Web. This provides access to a Pandora’s box of information, and is becoming a main means of access to other systems, such as those of the online search services. The Internet is explored more fully in the next chapter. There are also other contexts in which public access systems provide access to information or the ability to complete transactions. All of these systems can be viewed as public access systems, and as such they must be designed to accommodate the differing needs of user segments, and the information seeking tasks that such users may seek to perform. Figure 10.1 briefly compares some of the features of such systems.

In general, public access systems exhibit challenges in respect of both the user profile and the task. The user profile has two aspects, which contribute to make system design more demanding:

Users have a wide range of different educational backgrounds and levels of experience with the system. Users range from being subject domain novices and computer novices all the way to subject experts and computer experts. The degree of knowledge of the computer user and the domain experience should be reflected in the design of the user interface prompts, alerts and help facilities. Developers must also consider the needs of the system manager as user.

A large proportion of the population are naive and new users who need to be able to adapt quickly to different systems. Many users are also subject novices and their system use is constrained by their inability to appreciate what the system can be expected to contain.

The task is ill defined and there is an element of uncertainty in both:

what the user is likely to retrieve and accept as output from the process

the search strategies which will prove the most effective.

In the Internet environment, which will be considered further in the next chapter, the remoteness between information provider and information user is especially acute. Here, for example:

the designer does not know who the user will be

the user often does not understand how the search engines which they use to assist them with their search are conducting the search process.

Figure 10.1 Different types of systems contexts for knowledge organization

Online Search Services

What is an online search service? Online search services offer access to a wide range of databases. The online search services that we are primarily concerned with in this section are what might be described as the traditional online search services or search services. In the last few years these have been joined by consumer online services such as America Online, CompuServe and Prodigy, and a wide range of other organizations that mount databases on servers on the Internet. The online search services that we are concerned with here mount a range of databases upon a large computer system and offer users access to these databases, usually in exchange for a fee. Some search services have an international market and encourage and support users from all over the world (or, more accurately, the developed world). Other search services, while they may have some users in other countries, operate more as national services. The early search services were established in the late 1960s and the early 1970s. There are now well over 10 000 databases available via such search services and mounted on computers based at various locations throughout the world.

The intending user of such an online search service must be able to access the search service computer. This may be achieved with the use of a terminal or workstation that can be linked through a telecommunications network to the search service computer. This is usually a personal computer (PC) with communication software and a modem, or a PC linked to a server that has appropriate communications software mounted. A wide range of different networks can be used, but increasingly the search services are accessed through the Internet. Internet access to online search services that were previously accessed through other telecommunications networks can make it difficult to differentiate between an Internet server and an online search service. Both offer access to databases. The diversification of the roles of online search services also adds to the complexity. Here we define an online search service as a special category of Internet service that can be described thus:

An online search service seeks to mount a range of databases designed to meet the needs of a specific audience. It acts as an intermediary between the database producer and the end-user.

Online search services that provide access to a large number of databases convert the databases into a uniform format with some standardization in element names so that the basic commands and search techniques apply across all of the databases that are offered by a given vendor. The intending searcher needs some awareness of the range of search services that are available. Increasingly any one database may be available from several search services. Access to that database may be considerably cheaper, especially once telecommunications charges have been taken into account, via one search service than others. Alternatively, one search service may offer search facilities that support much more effective searching for a given topic than might be possible via another search service. Search services can no longer differentiate themselves on the availability of specific databases, but must offer customers other benefits, such as ease of searching, processing speed and competitive pricing. There are a number of different types of search service:

The traditional supermarket online search services that offer a range of 50 to 300-plus databases on behalf of database producers. Examples include: Dialog, DataStar and Questel Orbit. Although these online search services may offer many databases and may hope to be seen as a major presence in the information industry, continued commercial success depends on their ability to segment their market and to develop specialisms to match those segments. They are increasingly offering tailored services, such as KR ScienceBase, and Web-based services that support access to a range of services, such as Dialog Web.

Specialist online search services, such as DBE-Link, which offers German language and other European databases, and the search services offering access to business and financial databases, such as ICC. ICC deliver data online (with a Windows interface), offline, or via CD-ROM. Alternatively data can be delivered in bulk for integration into a company’s own database or Intranet, via either magnetic tape or electronic data delivery (EDD). Some search services, such as Information Access Company, started with a database catalogue that was focused on one subject but have now started to diversify.

Publishers as search services. A number of major publishers have entered the market-place as search services. Some of these will have gained experience of electronic publishing through CD-ROM publishing, whilst others have formed alliances with other online service suppliers, to be able to offer an integrated information solution, which embraces both bibliographic databases for locating information and full-text databases for document delivery. Examples are EBSCOsearch service, Information Access Search bank and UMI’s ProQuest Direct.

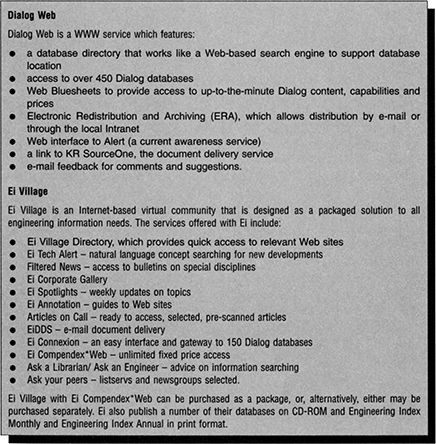

Platform independent search services, which provide access to databases on CD-ROM, the Web and client server platforms, possibly through a common user interface. Ovid Technologies are a good example of this type of search service. SilverPlatter is moving in this direction.

Bibliographic utilities that offer to specific communities access to a select range of databases, often at special rates. Examples are OCLC First Search and BIDS.

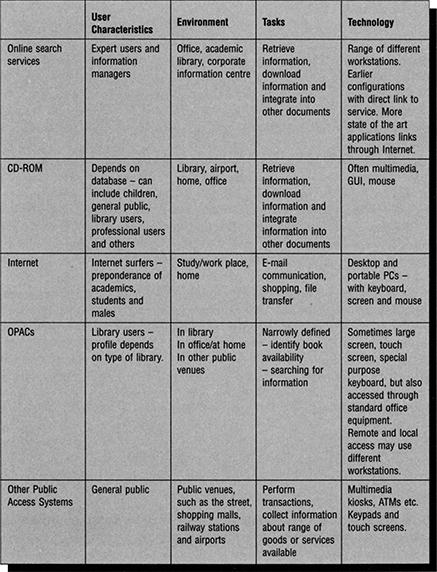

In general, online service suppliers are beginning to be able to respond to the long-standing need for common interfaces to tools, such as bibliographic databases and directories (including directories of Web sites) which indicate the location of information, and the full text of the document which contains information. The identification of a document and its delivery are much closer to being integrated into a seamless service. The more sophisticated offerings also offer access to other information channels, such as the databases mounted by other services, the contents of other Web sites, information collections such as libraries, and people as information channels. This could be described as an integrated information solution. Figure 10.2 describes two examples that seek to generate this integrated information solution. Such solutions need to be targeted to meet the needs of specific groups, and the service supplier must understand those needs, both in terms of the type of database to be accessed, and also in terms of specific features of interfaces and the most acceptable pricing strategies.

Figure 10.2 Some examples of integrated information solutions

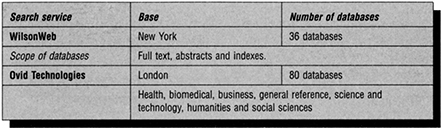

Figure 10.3 lists some of the major search services, shows the total number of their databases that may be accessed and gives some indication of the scope of the databases on offer. In addition to the range of databases available, many search services offer other services. These include current awareness services, access to web resources, Web directories, document delivery and databases on CD-ROM.

Searching Via Online Search Services

The first steps in an online search are the choice of search service and database. For most searches only a few databases might be appropriate, and having, for instance, identified the databases that cover the required subject area, further choice may be between only two or three databases. In general it is not sufficient simply to know the subject coverage of a database. An experienced searcher will, for example, also be familiar with the style of the indexing language, the time span of the database, and how items are selected for inclusion in the database. Often there may be no one database that will provide an exhaustive search and it may be necessary to consult two or more databases before a search is complete. The checklist below lists some of the factors that the experienced searcher will weigh in the selection of a database.

How to Guide: The Evaluation of Online Search Services

Databases, including the number, subject coverage, time span and language.

Search facilities. The elements of records that can be searched may differ from one search service to another. Certainly the field formats may vary and the field names may be different. Some systems offer more extensive facilities with regard to contextual or proximity searching and truncation. For source and full-text databases various special facilities may be required.

Interface options - these should include options to support both novice and expert searching. GUI and Web-based interfaces are common.

Formats for records and documents. Various formats are available for viewing the details of retrieved records. Sometimes it is possible for the searcher to select the elements that they require, but in searching other search services only a few standard formats are available.

Additional facilities. Many search services offer other facilities in addition to the basic online search facility. Often Selective Dissemination of Information (SDI) or document delivery services are available.

Support services. Most search services offer some support and training services. Help desks, training courses, manuals, newsletters and other search aids can influence the effectiveness of a searcher

Cost. Different search services have different pricing strategies. Some services are available on a subscription basis, whilst others are priced on a transaction basis. Some services allow a mixed of these two approaches, with customers, such as libraries, taking out a subscription for frequently used databases, and a transaction arrangement for less frequently used databases. There will also be special rates for additional services such as SDI or document delivery. The cost of telecommunications should also be considered, and this may vary between and within countries.

Experience. The searcher’s experience with a specific search service may be an important factor in determining his/her search effectiveness. Thus, from the searcher’s point of view it is important not only to assess the specific features of the search service, but also to examine his or her own skills.

CD-Roms

Introduction

Optical discs, and those specifically in the form of CD-ROMs, have become increasingly important as a medium for the storage and dissemination of information during the 1990s. CD-ROMs can be purchased by users and consulted at their own workstation. The price of many discs is currendy such that many disc users would not buy them for personal use, but organizations and libraries buy discs on behalf of end-users. In this context, CD-ROMs represent a means of access to information alternative to online access to external databases via telecommunications networks, including the WWW. When the database recorded on the CD-ROM is the full text of a document such as a directory or an encyclopaedia, CD-ROMs may challenge the market position of the printed book. All three media are likely to continue to coexist, with each finding its market niche.

Providing Access to CD-Roms and Network Configurations

Network configurations have a significant impact on the way in which CD-ROMs can be exploited, especially in a multi-user environment. The basic stand-alone CD-ROM workstation provides a single user with access to a single disc. Clearly this configuration is incompatible with a networked environment where users are accustomed to access shared databases via their own workstations. The ideal CD-ROM configuration offers multi-user access to many databases in a way that allows the integration of databases on CD-ROM with other databases used by the information-seeker. First, we consider the basic stand-alone configuration.

CD-ROM drive linked to a stand-alone PC

The basic components of the stand-alone configuration are:

a stand-alone PC

a CD-ROM drive and appropriate software

if required, a printer.

Most PCs have an integral CD-ROM drive, but if this is not available, the PC needs a spare expansion slot via which the drive can be linked, together with device-driver software, which tells the PC that a CD-ROM drive is connected. If hard-copy printouts of the results of a CD-ROM search are required, then a printer is essential. The choice of printer depends upon the environment and the relative priorities associated with noise, print quality and price.

In the early days of CD-ROM, compatibility was a very significant problem. There is much more standardization now, but it is still wise to check that all of the hardware and software components work with one another. The software situation is a little complex. In addition to the operating system of the microcomputer it is also necessary to have:

retrieval software, which supports the searching of the CD-ROM database. This will be supplied by the producer of the CD-ROM product

installation software, which controls the installation of the product on the user’s equipment, and supports the setting of configuration options, such as user-defined passwords, and equipment specification.

Networking internal CD-ROM drives

There are two ways to network stand-alone drives:

Place the machines with their internal drives attached on a network. Users need to place the disc in their drive before they can use it

Peer-to-peer networking, where one computer acts a the host machine, with the CD-ROM drive on that machine, and other PCs able to request access to the database This approach is easily implemented through Windows for Workgroups, but may be less easy to implement on other platforms; further, the performance depends on what the host is doing.

Using file servers and jukeboxes

The file server on a network can be used to provide access to the discs and software, rather than installing the software on individual machines. This file server can be the standard network file server, or may be a dedicated CD-ROM server or optical file server. This can either be directly plugged into the server, or logically connected across the network to the server. A dedicated server is preferable. The load on the network server may be too great, and not all CD-ROM titles will work off the server if they are not network aware. With a CD-ROM server it is easier to have all the discs and their software in one place for updating and general maintenance, and the configuration is expandable, and offers support for higher capacity jukebox systems.

A jukebox is a device that offers access to a large number of CD-ROM discs. Unlike CD-ROM drives, jukeboxes do not have a read head available for each individual disc. When a user wants to access a particular title it will be loaded by the jukebox and returned to its position after use in the same way as in audio jukeboxes. However, if there is simultaneous demand for more discs than there are drives the need to swap discs can slow down system performance.

Pre-caching

Pre-caching is the most recent approach to offering more speedy access to CD-ROM. Some publishers allow the user to copy the data from the CD-ROM disc directly on to a large magnetic hard drive. Pre-caching reduces the requirement for multiple CD-ROM drives, and more users can access the database at any one time. There are, however, a number of disadvantages:

The permission (from database producers and publishers) to pre-cache can be expensive.

Not all publishers offer pre-caching.

The databases have to be updated. When using CD-ROM discs this is achieved by simply replacing the old disc; with a pre-cached system the disc has to be copied across.

Internet access

Another type of pre-caching can be achieved through Internet access; ultimately this has very little to do with CD-ROM, since the data is not being held on CD-ROM. Instead it is held on a remote site, either belonging to the publisher or one of their appointed agents. The software to access the databases is held locally, with a pointer to where on the Internet the retrieval interface should be looking. This option is being offered by a limited number of CD-ROM publishers but is likely to become a more significant option. This solution has many of the same advantages as pre-caching, and in addition the publisher’s technical support department is charged with the task of keeping the system up and running on a 24-hours, 7-days-a-week basis. Updating of databases is the responsibility of the publisher, and can be done much quicker and, if appropriate more frequently, since the publisher can simply upload the data. The only drawback is that access to the data is subject to any Internet problems.

Figure 10.4 Comparing CD-ROM and online search services

Figure 10.4 compares CD-ROM and online services.

CD-ROM Publishers and Publishing

Nearly all new PCs come equipped with CD-ROM drives; this provides an enormous installed base of CD-ROM drives. The bulk of the retail CD-ROM sales are multimedia with games and children’s titles, followed by adult reference, being the most popular sellers. libraries supplement this personal ownership by offering access to multiple titles. All projections anticipate a significant continued growth in the market for CD-ROM.

CD-ROM publishing is a relatively easy to market to enter, and consequently there are a large number of CD-ROM publishers. Most publishers are not prolific, and many have only a single product. Publishers may be engaged in various other aspects of the information industry. CD-ROM suppliers can be broadly divided into the following categories:

Supermarket CD publishers, with a very significant catalogue of databases, which are produced by other organizations. Examples are Information Technology Supply Ltd and SilverPlatter. Another group is the online service services, such as Dialog with their KR OnDisc.

Database producers, who will probably also be making their databases available via online and WWW media. Examples are CA (Chemical Abstracts) on CD, Wilson Business Abstracts, Mintel CD and Biosis GenRef on Compact Disc.

Publishers. For example, Chadwyck Healey who started by publishing their own databases on CD-ROM but have added other HMSO and related documents, Blackwells and Wiley

Document Supply Centres (such as the British Library) who make serials, books and conferences available on CD-ROM.

The market is still volatile, with new products entering the market as others leave. Nevertheless the number of titles and associated publishers continues to grow.

Conducting a CD-ROM Search

CD-ROM products have been specifically designed for ease of use and to facilitate end-user searching. Many offer both novice and expert mode interfaces. Retrieval facilities are similar to those that might be expected in any information retrieval product. For example, Boolean logic, truncation, field-specific searching, phrase searching and other facilities are featured in most of the software used for retrieval in CD-ROM databases. An example was given in Figure 4.6. The unique feature of CD-ROM is the interface and dialogue design.

Some databases and user groups demand special information retrieval facilities. For example, Disclosure’s Global Researcher has features that support the searching and analysis task that a company researcher might need to perform, including those that:

identify companies by name, ticker symbol, geographic location, line of business or financial criteria

rank companies based on financial performance

perform instant point-and-click peer group comparisons

analyse financial data using an Excel add-in

create user-defined reports and ratios

view real-time electronic filings.

How to Guide: Evaluating Information Retrieval Features on CD-ROM

The availability of the following features should be sought

Index

- Browse index

- Number of postings

- Cross references

- Thesaurus

Search structure

- Term selection from index

- Term selection from record

- Case sensitivity

- Search types

- Combine searches

Search features

- Boolean

- Truncation

- Adjacency/proximity

- Positional

- Arithmetic

Search profile management

- Speed of performance

- Save searches

- Purge old searches

- Search status

- Set and query management

- Number of search sets

- Search history display

- Search modification

- Search selection

- Statistics gathering.

Interface/dialogue design

CD-ROMs were one of the first media that were designed with the expectation that the end-user would perform searches without the intervention or support of an intermediary. When CD-ROMs first entered the market-place, online search services were operating primarily through command-based interfaces. Even early CD-ROM interfaces made extensive use of colour, graphics and menus. Most CD-ROMs today use GUIs. Although the Web-based interfaces, which use HTML, are a significant improvement on command-based interfaces, GUIs of CD-ROMs are becoming ever more sophisticated. Animation, sophisticated graphics, multimedia capability such as is used in embedded video clips, and help systems that talk to the user, are some of the options that are available on some CD-ROMs.

Multi-tasking is another feature of GUIs. In CD-ROM applications this could, for instance, be used to access an online database, while still connected to the CD-ROM database, and possibly to compare the results of the two searches.

The future for CD-ROMs

The number of publishers and products in the CD-ROM market-place is continuing to increase. A major issue for the future of the medium is the continued development of a consumer market. Figure 10.4 has already summarized the strengths of competing technologies. In addition to the Internet, CD-ROM may be overtaken by other technologies, such as digital versatile disc (DVD).

Specific developments that are already under way and that can be expected to continue include:

Continuing growth in the number of CD-ROM titles. There has been significant recent growth in both the business and professional market-place and the consumer market-place.

Price strategies are likely to consolidate in such a way that they recognize the different market sectors for different products. This will be partly content dependent with, for example, encyclopaedias and dictionaries priced as consumer products, and bibliographic databases priced for library and corporate purchase. Greater transparency and simplicity of pricing strategies for networked use of CD-ROM will be demanded by customers.

Further integration of technologies, with CD-ROM being used for core information delivery, and online access, often via the Web, being used for more current or real-time information to update the data available on the CD-ROM. Consumers will pay for immediacy for information that is only required occasionally. Frequently required material will be already paid for, and available on disc. Also the high capacity of DVD may be attractive for some applications

Increasing sophistication of search interfaces, with tailoring to the requirements of specific user groups and types of databases. SilverPlatter’s Search Advisor, which works with a GUI may be a model for the future. An intelligent retrieval client, the Search Advisor offers the tools used by professional searchers to develop search strategies, and supports novice searchers in their use of these tools. CD-ROM multimedia databases should be at the leading edge of the enhancement of interface design.

Increased sophistication customer support from suppliers. KR, has, for instance recently launched Crossroads, a Web-based service that provides a forum for users to share their expertise and knowledge, and Learning Center which links visitors to a range of training options. These include web training sessions that are webcast live to participants, and prepared instructional modules.

The use of Intranet technology to provide access to networked CD-ROMs. For example, KRSite offers access to the Knight Ridder collection of CD-ROMs via corporate intranets.

Online Public Access Catalogues

Introduction

Online public access catalogues have become a popular option for access to the resources of the collections of libraries, library consortia and other remote collections of information resources. They are one type of information retrieval system, but are distinct from other services in that the focus is on access to:

collections of library resources and community information

books, as opposed to, say, journal articles or Web-based resources.

Early OPACs provided access only to the documents in individual library collections, but as the options for networking have become more advanced the range of different collections to which users can gain access through a library OPAC has developed. Other developments have taken place in respect of the interfaces and search facilities offered by those interfaces, as discussed below. In addition, the range of different locations in which OPACs can be used has expanded. In academic libraries, for example, OPACs are frequently available in staff offices over the university network. Some public libraries are experimenting with public access kiosks in public areas such as shopping centres and community centres. Online public access catalogues are now an important shop window on library resources.

Library Management Systems

Online public access catalogues are created and maintained through library management systems. Such systems have a catalogue maintenance module and an OPAC module. There may also be a separate community information module, with an interface that is linked to that of the OPAC. Other modules in library management systems (LMSs) support the management and control of the library stock and its delivery to users; typical modules are those to cover circulation control, ordering and acquisition, serials control and management information.

There are a wide range of different library management systems in the marketplace, designed for different types and sizes of library collections. Figures 2.3, 2.4, 2.5 and 2.6 show a search on an OPAC in one of these systems. Almost all large academic libraries have adopted a computer-based system. Most public libraries have also computerized, although a number of smaller authorities have been slower to take the plunge. In the large-systems market there is an increasing concentration on vendors maintaining existing customers, and continuing to upgrade their product so that existing customers do not switch systems. Clearly any library may review systems and choose to upgrade them by switching to another supplier from time to time. The mid-range and smaller-systems market is the area in which there is still growth. Smaller colleges, and special libraries in various sectors, are still entering the market-place, and there is more volatility in systems vendors. A number of the smaller systems are specifically marketed in the school library sector. However, even here, the established players are consolidating both their product and their market position.

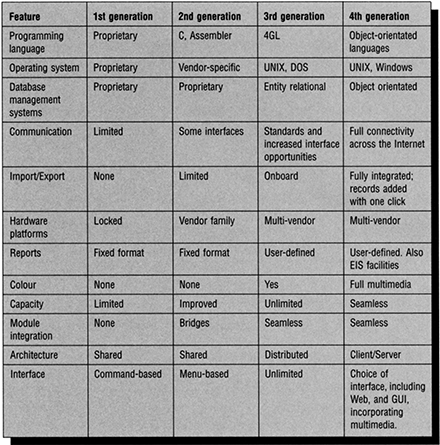

All systems suppliers continue to upgrade their systems, and enhancement of the OPAC function has been central to the changes between the different generations of library systems. Figure 10.5 is a useful summary of the differences between the four generations of library systems. The latest releases of systems generally fall somewhere between the third- and fourth-generation systems, depending on the sophistication of their facilities for integration and interconnect-ivity. To some extent the fourth generation has yet to be realized. This profile of the four generations of LMS is a useful summary of the way in which systems have developed over the past 20 years.

Figure 10.5 Library management systems by generation

The first generation of library management systems were developed on a module-by-module basis. There was very limited integration between modules, with systems either developing circulation control or cataloguing as a priority. Thus, the first edition of this text was able to divide systems according to their major function. Gradually suppliers developed a set of modules and, as they did so, started to recognize the benefits of linking these modules. Systems grew from an initial focus on, say, circulation control. Database structures differed, and might be described as proprietary. It was difficult to make any generalizations about database structure. Third- and fourth-generation systems are integrated systems based upon relational database structures.

In other respects also, first-generation systems demonstrated their lineage. They were developed to run on specific hardware platforms, and used proprietary software languages and operating systems. Some systems were specifically designed to be sold as part of an integrated hardware and software package as a turnkey system. Second-generation systems ran on a wider range of hardware platforms, but it took the introduction of UNIX- and disc operating system (DOS)-based systems for systems to become much more portable, between platforms. Fourth-generation systems are generally UNIX or Windows based.

Communication between systems was also generally non-existent in earlier systems. Links between systems for specific functions were a feature of second-generation systems. It was possible to import or export data to specific systems, but not generally. Third-generation systems embodied a range of standards that were a significant step towards open system interconnection, but a number of issues associated with end-user access and interfaces required resolution. Also implementation of systems that employed all of the appropriate standards was only gradual. Fourth-generation systems feature client/server architecture and modules that facilitate access to other servers over the Internet.

The user’s interaction with the system has also become more fruitful and straightforward as systems have moved through the generations. For library managers, reports from early systems were very limited and there was little opportunity for users to define their own reports. The range of standard reports available in third-generation systems is wide, and users may, in addition, define their own reports. The latest executive information system (EIS) modules will allow managers to manipulate data and investigate various scenarios, and thereby have the potential to be a full decision support tool.

The user interface has also improved beyond recognition. Colour became standard in third-generation systems. Graphical user interface features, such as windows, icons, menus and direct manipulation, have become the norm. This is in stark contrast with the crude command-based interfaces of the early online systems, or the need to wrestle with batch processing and printed reports. Fourth-generation systems allow access to multiple sources from one multimedia interface. This very much enhanced user interface is symbolic of the change in user or customer focus in systems over the generations. Early systems were designed primarily for staff access. Online public access catalogues started to emerge in second-generation systems. Third-generation systems saw much more sophisticated GUI-based user interfaces. The fourth-generation OPAC can be accessed through a range of interfaces depending upon the client workstation and the user. This range embraces public access terminals with limited functionality to sophisticated GUIs with a powerful range of search facilities.

Catalogue Database Creation

Online public access catalogues depend on the quality of the underlying database. One of the early advantages of the use of computer-based cataloguing was the opportunity to reduce the resources dedicated to the creation of catalogue records. There were two main ways in which this effort could be reduced: by the sharing of catalogue records, so that each individual library did not create its own records; and, because there was no longer a need to engage in the time-consuming task of filing of catalogue cards. The first of these, the sharing of catalogue records, was facilitated by the work of a number of library cooperatives and centralized cataloguing services. These cooperatives and cataloguing services took responsibility for the creation of records that could be used by subscriber or member libraries. Major agents in this were the library of Congress and the British library (BL). Other networks whose contributions have also been considerable include OCLC, Research Libraries Group (RLG), Birmingham libraries Co-operative Mechanization Service (BLCMP) and London and South East Region (LASER). In order for these ventures to be successful, it was important that standards were adopted to support the creation of shared catalogue records. These standards have been discussed in earlier chapters of this book; they include AACR and MARC, and the Dewey Decimal Classification Scheme. This need to spread the work in the creation of catalogue records has, in fact, been responsible for the extent of standardization in library cataloguing, and has a major impact on the quality and nature of the databases to which OPACs provide access.

Key features in a cataloguing module are:

data entry

downloading

authority control.

Easy data entry for local creation of records is important. It is usual for systems to use the same record for the ordering and acquisitions function as is used in the cataloguing module. Entry is via formatted screens with word processing-type facilities. Field labels and other areas of the screen should be protected, and data entry in some fields, such as the ISBN field, should be validated to ensure that the data entered are in the correct format

As regards the record format, the MARC record format is a central consideration. External records from the bibliographic utilities are generally in one of the MARC record formats. Local systems must at least be able to handle the MARC record format. Some systems are totally MARC based, others can accept records in the MARC format and convert them into an internal format. Where alternative formats are available, systems usually allow libraries to define fields for the bibliographic record. Most systems automatically update index files as soon as the record has been added to the file, so that retrieval is possible immediately. A wide range of different types of indexing may be possible.

Records from external databases may be added from tape, or via downloading direct from the files of the bibliographic utilities. A further option is to acquire records on CD-ROM and to download records from CD-ROM databases.

Authority control is important where the form of index terms or headings, such as author headings, or subject index terms, need to be controlled. Libraries maintain an authority file in order to improve consistency in indexing. Records in this file may be created locally or drawn from externally available files such as the Name and Subject Authority files of the library of Congress. The authority file can usually be consulted during indexing and cataloguing, possibly by display in a separate window, and new headings are immediately added to the authority file, with an opportunity to review or authorize recently added headings at a later date. Sometimes it is also possible to add cross-references or related terms to the authority file, and these may be displayed in the OPAC. The subject authority file may take the form of a thesaurus that displays the full range of uses for related, narrower and broader terms.

Facilities to support catalogue database creation continue to improve, and these should lead to continuing increases in the efficiency of catalogue creation and updating, and the quality of the database. Two areas in which such improvements have focused recently relate to connectivity and authority control:

Improved connectivity and interfaces support faster execution of library management operations in a number of functions. For catalogue creation this leads to improved capture of MARC records. For example, a database of such records on CD-ROM may be accessed. On the entry of an ISBN, either through scanning a bar code, or through keying, the MARC record is instantly displayed for any necessary editing. It is then automatically added to the database. The streamlining of this process is a particular asset for any library and resource collection that has yet to convert their catalogue records into a MARC format

Improved authority control. Amid the continuing debate concerning whether, with the availability of natural-language searching, it is necessary to control index terms and headings, a number of systems have enhanced their facilities for the control of index terms or headings. Authority control may be exercised in relation to subject index terms or headings, titles and author headings or access points. Authority control systems have been added by some vendors and enhanced by others. For example, some now allow a greater range of relationships to be used in the thesaurus. Where thesauri are available, and this is mainly in the systems marketed to the special library sector, these are often now displayed in sections via windows, and may thus be consulted during either indexing or searching much more easily than previously. More sophisticated authority control, with, in the most advanced systems, multiple authority files, and validation of a range of different types of heading on entry is also available. Thesauri may also be used to provide SEE and SEE ALSO cross references.

Cataloguing consistency can be improved further through spell checkers and style checkers, and de-duplications tools. If records are to be shared it will be necessary to know which spell checker has been used. Catalogue tidying and global amendment software will improve the quality of catalogue databases. The cataloguing of electronic documents still presents a number of challenges, but also opportunities. Free-text searching on the text of electronic documents offers access routes not traditionally available in catalogue records of print documents. Also there is scope for further enhancement of links between citation records and multi-media document types, and for further work on indexing of, for example, images or video clips.

Interfaces and Search Facilities

Online public access catalogue interfaces need to offer facilities for both the searching of the catalogue database and the display of records.

Online public access catalogues have been available in some systems, for approximately ten years. During that period OPACs have passed through three generations. First-generation OPACs were derived from traditional catalogues or computerized circulation systems. Access was via author, or title (as a phrase), classmark and possibly subject heading (as a phrase), and acronym key such as author-title acronyms. First-generation OPACs expected exact matching of terms and were intolerant of user mistakes. These OPACs were acceptable for known-item searching and offered menu-based access, but this access was based on limited search facilities.

Second-generation OPACs began to rectify some of the limitations of the first systems. Systems designers started to incorporate some of the facilities to be found in other text information management systems and the software used by the search services. Second-generation OPACs offered much better search facilities based upon keyword searching and post-coordination of keywords. Usually these OPACscouldbeoperatedwithacommandlanguageasweUasthroughamenu-based interface. Although second-generation OPACs were a great improvement, two problems still needed to be addressed. Browsing through records remained difficult and it was necessary to work through different menu screens, while the large size and wide coverage of catalogue databases often led to many false drops.

Third-generation OPACs use a natural-language interface, so that the users may input their search strategy as a natural-language phrase. Interfaces and search facilities began to improve with the entry of the early GUI-based OPACs. The latest OPACs offer both touch screen for public access and full GUI for full functionality for more experienced users who wish to pursue complex search strategies across a number of different sources. A wide range of search facilities such as truncation, and proximity searching is becoming common; access to and prompts for the use of these are embedded in the interface.

Once records have been identified there are a number of ways in which they may be displayed. Some systems display the index or a listing of brief records before a full record is displayed; others, if there is only one match, will show the record directly. Usually the full record display includes holdings information relating to individual copies, as well as the basic bibliographic data. Where such data are available to the public, it is often necessary to consult another window to discover the loan status of the document. Record displays may be library denned. Security procedures may mask confidential information. For non-matches, some systems show the index. Since non-match will be relatively frequent, browsing of the index and/or a list of brief records is common.

Graphical user interfaces offer point and click, icons, pull-down menus, cut, copy and paste, and multi-tasking. So, as explained in Chapter 4, users can develop a search strategy in one window, call up a thesaurus display in another window, and consult help, or view the results of their search in yet a further window. When a successful search has been completed, components of documents may be integrated into other documents through a word-processing package or, alternatively, documents may be ordered through a document ordering service. Web interfaces are widely available so remote users can access the library OPAC through the Web.

Online public access catalogues can be further enhanced by offering multimedia interfaces and access to multimedia information. This can be achieved through multimedia objects linked to bibliographic citations, in such a way that the multimedia objects can be called by clicking on a button in this citation.

Multiple client options, which means that the client can be anything from a dumb terminal, a lower specification PC or network computer to a fully configured high-specification PC with client software, will facilitate access from a greater range of networked workstations. The interface displays differently on each client, but the client may access a number of applications through the same interface, thus making it easier for the user to develop familiarity with the interface that is available through their specific client. On the other hand, where users move between workstations to obtain access to the same database, this variation may be confusing.

Access to a range of other self-service functions, such as self-issue and self-renewal, and community information is often offered through the same interface as the OPAC. There has been considerable debate about the effect that self-service may have on customer perceptions of the quality of the library service, and the effect that remote renewal may have on control of library stock, but potential savings in staff time are attractive. Some of these applications are concerned with public access terminals in a kiosk format, and links to the Internet. Public access terminals are often based on touch screens. These interfaces are generally heavily reliant on menus in which the user selects an option by touching the screen. The range of search facilities is more limited than with terminals that include keyboard access. Kiosks are designed for use in any location in which there is significant footfall, including public libraries, shopping centres and railway stations.

Community information may be one of the first categories of information that libraries wish to make accessible over the Internet, or via public access kiosks. The core of this service is, often, lists of names and addresses of contacts such as local organizations. Such files may extend to many types of other information, including information about local leisure facilities, employment opportunities, children’s activities and citizens’ information. A community information module allows a library to develop its own database of whatever information it might like to offer its public.

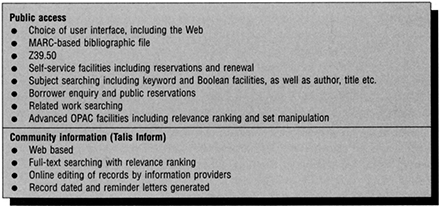

Figure 10.6 shows features available in BLBMP TALIS in respect of public access modules and community information modules.

Figure 10.6 Features available in BLCMP TALIS 298

The Future for OPACS

Libraries are moving into a position where they will be able to encourage the use of electronic resource by large numbers of remote users for payment, or will be able to limit access to specific users. Online public access catalogues are a shop window in such an environment. External users must be able to access the library’s OPAC but, in addition, library users may use the OPAC to access a wide range of other Internet resources. The OPAC can act as a window on the world of information resources. Each user will have one or more personal logins, allowing preferences, rights and activities to be stored for reuse. Search statements might be shared among users. Web browser concepts such as structured bookmarks, and back-tracking will become widespread. Users will use the OPAC as one of a number of methods to maintain personal files without rekeying data. Users need to be able to store and reuse search statements and results. Personal documents can be linked directly to library citations or electronic documents (e-documents), and can be submitted as a potential library acquisition or supplied in response to a library document request. Client/server computing will allow users to select a search interface for a task, rather than accept a standard set of options.

Online public access catalogue interfaces need to be designed for different types of users. Dynix’s ‘Kids Catalogue’ is an early example. Facilities for disabled people, and particularly the visually impaired need to be incorporated into library OPACs. In all of this, users need the ability to choose their OPAC interface.

Most libraries now provide community information on Web pages, rather than via a library management system. Increasingly this may involve the publication of web documents, and even web journals. This may necessitate converting documents to HTML format or the use of a document management system. The same machine must be able to access these pages and the LMS, other applications on the local area network (LAN), such as CD-ROMs, the intranet and the Internet. It is important that the look, feel and functionality of interfaces to these different resources be consistent

Systems may also facilitate user access to commercial databases, other library resources and document collections. Metainformation about WWW resources needs to be available. The systems must tackle issues concerning liability, control of copyright, licensing and collecting of appropriate payments. Asset trading agreements must be forged across the information chain. Such systems may also need to accommodate the assessment and evaluation of resources by those seeking to acquire them. Systems will need to be able to manage who is allowed access to what, when, for how long or to what maximum charge, the payment strategy and associated rights. They will need to manage copyright issues as an integral function, and will need to be linked to the systems of publishers, editors, indexers, picture libraries and authors.

The other side of access is security. Security must be built in, and be based on a comprehensive system of access rights, permissions, rules and parameters. Security also includes comprehensive, efficient and fast system backup and restoration of lost data. Security will increasingly be linked to charging. Proving access to the wealth of Internet resources is expensive; Smartcards that record customers transactions are likely to be increasingly used to support charging, and may also be used as the security device for access to a range of organizational and external information resources. They could also be used with self-issue kiosks.

In conclusion, the future offers a number of options, but there are unlikely to be generic solutions that will accommodate every library and information management function and task. Users will continue to choose information sources on the basis of convenience of use and access, and cost. Although future systems may offer users many opportunities to participate in systems design and to tailor interfaces and the collection of resources to which they have access, locating good, reliable and validated information is in some sense becoming more time-consuming and difficult, not easier, and there will remain a role for an information guide. library management systems will be an important tool in the armoury of the information guide.

Summary

This chapter has reviewed a number of systems contexts in which the principles of the organization of knowledge are to be encountered. Online search services offer access to a range of databases, often over the Internet. These resources include both source and reference databases. Some of these databases can alternatively be acquired on CD-ROM so that an organization or individual consumer can license the complete database. Organizations and libraries often network these databases, sometimes using Internet or intranet technology. Most libraries also use the OPAC modules of a library management system to provide online access to their catalogue databases. This access may be provided in the library but, often, catalogue databases can be accessed remotely, either through a local area network or over the Internet or Web. The issues associated with the organization of knowledge and, correspondingly, the search facilities offered in all of these different types of applications have many common features.

Further Reading

CD-ROM

Adkins, S. L. (1993) CD-ROM: a review of the 1992 literature. Computers in Libraries, 13 (8), 20–53.

Armstrong, C. J. and Hartley, R. J. (1997) Keyguide to Information Sources in Online and CD-ROM Database Searching. London: Mansell.

Batterbee, C. (1995) Open access CD-ROM in public libraries. Aslib Proceedings, 47 (3), 63–72.

Batterbee, C. and Nicholas, D. (1995) CD-ROMs in public libraries: a survey. Aslib Proceedings, 47 (3), March, 63–72.

Beheshti, J. (1991) Retrieval interfaces for CD-ROM bibliographic databases. CD-ROM Professional, 4 (1), 50–53.

Bevan, N. (1994) Transient technology? The future of CD-ROM in libraries. Program, 28 (1), 271–331.

Biddiscombe, R. (1992) Networking CD-ROMs in an academic library environment British Journal of Academic Librarianship, 6 (3), 175–183.

Black, K. (1992) CD-ROM networking: the Leicester Polytechnic experience. Aslib Information, 20 (7–8), 288–290.

Bosch, V. M. and Hancock-Beaulieu, M. (1995) CDROM user interface evaluation: the appropriateness of GUIs. Online and CDROM Review, 19 (5), 255–270.

Brackel, P. A. (1994) Implications of networking CD-ROM databases in a research environment. South African Journal of Library and Information Science, 61 (1), 26–34.

Bradley, P.. (1996) UKOLUG Quick Guide to CD-ROM Networking. London: UK Online User Group.

Bradley, P. (1997) Going Online, CD-ROM and the Internet, 10th edn. London: Aslib.

Bryant, G. (1993) Combining online and disc. Online and CD-ROM Review, 17 (6), 396–398.

Budd, J. M. and Williams, K. A. (1993) CD-ROMs in academic libraries: a survey. College and Research Libraries, 54 (6), 529–535.

Carlton, T. (1995) CD-R on the cheap? CD-ROM Professional, 8 (4), 20–27.

Cawkell, T. (1996) The Multimedia Handbook. London: Routledge

CD-ROM Consistent Interface Committee (1992) CD-ROM consistent interface guidelines: a final report CD-ROM Librarian, 7 (2), 18–29.

Clarke, K. (1993) New OVID software from CD PLUS Technologies. CD-ROM Professional, 6 (6), 230–232.

Clausen, H. (1997) Oneline, CD-ROM and Web: is the same difference. Aslib Proceedings, 19 (7), 177–183.

Diamond, S. (1993) Creating text and image CD-ROMs: getting it right the first time. CD-ROM Professional, 6 (6), 128, 130–131.

Falk, H. (1994) CD-ROM recording in every library Electronic Library, 12 (5), 304–307.

Fecko, M. B. (1997) Electronic Resources: Access and Issues. London: Bowker-Saur.

Guenette, D. (1996) The CD-ROM online connection. CD-ROM Professional, 9 (3), 30–44.

Hanson, T. and Day, J. (eds) (1994) CD-ROM in Libraries: Management Issues. London: Bowker-Saur.

Jasco, P. (1996) The Internet as a CD-ROM Alternative. Information Today, 13 (3), 29–31.

Kirby, H. G. (1994) Public library case study: CD-ROM at Croydon Central library. In T. Hanson and J. Day (eds), CD-ROM in Libraries: Management Issues. London: Bowker-Saur.

Knight, N. H. (1997) Information metering: issues and implications. Information Services and Use, 17 (1), 1–4.

Koster, D. D. (1993) CD-ROMs: stand alone or networked. Library Media Quarterly, 21 (2), Winter, 127–128.

Lambert, J. (1994) Managing CD-ROM services in academic libraries. Journal of Library and Information Science, 26 (1), 23–28.

Large, J. A. (1989) Evaluating online and CD-ROM reference sources. Journal of Librarianship, 21 (2), 87–108.

Lopez, N. K. (1997) Gale Directory of Databases. Vol. 1 Online Databases and Vol. 2 CD-ROM, Diskette, Magnetic Tape, Handheld and Batch Access Database Products. Detroit, MI: Gale Research Inc.

Ma, W. (1998) The near future trend: combining Web access and local CD Networks; experience and a few suggestions. Electronic Library; 16 (1), 49–54.

Machovec, G. S. (1997) Electronic journal market overview. Serials Review, 23 (2), 31–44.

McBride, J. (1994) CD-ROM authoring and mastering: searching for the tools to bring it all together. CD-ROM World, 9 (1), 53–55.

O’Leary, M. (1997) Online comes of age. Online, 21 (91), 10–20.

Richards, T. (1995) Proliferation of CD-ROM retrieval software: stability at last Computers in Libraries, 15 (10), 61–62.

Ronen, E. (1994) Internet CD-ROM survey. Electronic Library; 12 (6), 372–373.

Rowley, J. (1995) Issues in multiple use and network pricing for CD-ROMs. Electronic Library; 13 (5), 483–487.

Saffady, W. (1996) The availability and cost of online search services. Library Technology Reports, 32 (3), 337–456.

Stratton, B. (1994) The transiency of CD-ROM? A reappraisal for the 1990’s. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 26 (3), 157–164.

Tenopir, C. (1996) Has online made CD-ROM obsolete? Library Journal, 12 (16), 33–34.

Wiedemer, J. D. and Boelio, D. B. (1995) CD-ROM versus online: an economic analysis for publishers. CD-ROM Professional, 8 (4), 36–42.

Worley, J. (1996) The CD-word: reflections on user behaviours and user service. Electronic Library, 14 (5), 411–413.

Yeardon, J. (1995) Experiences with SilverPlatter Electronic Reference library at Imperial College. Program, 29 (2), 169–175.

Online Search Services

Amor, L. (1996) The Online Manual: A Practical Guide to Business Databases, 5th edn. Oxford: Learned Information.

Amor, L. (1997) Online Company Information 1997: The Directory of Financial and Corporate Databases Worldwide. Oxford: Learned Information.

Armstrong, C. J. and Hartley, R. J. (1997) Key Guide to Information Sources in Online and CD-ROM Database Searching, 2nd edn. London and Washington, DC: Mansell.

Armstrong, C. J. and Madawar, K. (1996) Investigation into the Quality of Databases in General Use in the UK. British library Research and Innovation Reports No. 11.

Basch, R. (1993) Annual review of database development Database, 16 (6), December, 29–41.

Bates, M. J. (1996) The Getty end-user online searching project in the humanities: report No. 6: overview and conclusions. College and Research Libraries, 57 (6), November, 514–523.

Bjorner, S. (1994) Get ready, get SET, go for more control on Dialog. Online, 18 (1), January, 103–108.

Chishti, S. H. (1993) CD-ROM vs online: a comparison of PsycLTT (CD-ROM) and PsycINFO (DIALOG). Reference Librarian, 40, 131–155.

Foote, J. B., Harrison, M. M. and Watson, M. (1997) Electronic library resources: managing the maze. Resource Sharing and Information Networks, 12 (2), 5–17.

Galt, J. S. (1997) Does the future of online industry lie in individually customised services? How online hosts are adapting to the future. In D. I. Raitt et al (eds), Online Information 97: Proceedings of the International Online Information Meeting, London 9–11 December 1997, pp. 13–18. Oxford: Learned Information.

Head, A. J. (1997) A question of interface design: how do online search service GUI’s measure up? Online, 21 (3), May-June, 20–29.

Jeffcoate, J. (1993) Multimedia in the business market: is there a multi-media market? Information Management and Technology, 26 (5), September, 222–225, 228.

Online company information (1997). Oxford: Learned Information.

Online Information (1993, 1994, 1995, 1996) Proceedings of the 17th-20th International Online Information meeting. London, December 1993,1994,1995 and 1996. Oxford: Learned Information.

Poynder, R. (1996) STN International: the scientific and technical search service. Business Information Review, 13 (2), September, 183–190.

Rehkop, B. L. (1994) Cypress: a GUI interface to Dow Jones News/Retrieval. Online, 18 (1), January, 72–75.

Scott, J. (1996) Online access to international newspapers and wires: a status report. Database, 19 (4), August-September, 42–49.

Storey, T. and Dalrymple, T. (1996) On the Web with OCLC First Search and NetFirst. OCLC Newsletter; (220), March-April, 34–35.

Tenopir, C. and Bergland, S. (1993) Full text searching on major supermarket systems: DIALOG, DATA-STAR and NEXIS. Database, 16 (5), October, 32–42.

Tenopir, C. (1996a) Moving to the information village. Library Journal, 121 (4), March, 29–30.

Tenopir, C. (1996b) Generations of online searching. Library Journal, 121 (14), 128, 130.

Vickery, B. and Vickery, A. (1993) Online search interface design. Journal of Documentation, 49 (2), June, 103–187.

Webber, S., Baile, C., Cameron, A. and Eaton, J. (1994) UKOLUG Quick Guide to Online Commands. 4th edn. London: UK Online User Group.

Online Public Access Catalogues

Alper, H. (1993) Selecting Heritage/Bookshelf-PC for the District library, Queen Mary’s University Hospital, Roehampton. Program, 27 (2), 173–182.

Batt, C. (1994) Information Technology in Public Libraries, 5th edn. London: Library Association.

Batt, C. (1995) The last migration Public Library Journal, 10 (6), 159–161.

Cherry, J. M., Williamson, N. J., Jones-Simmons, C. R. and Xin Gu (1994) OPACS in twelve Canadian academic libraries: an evaluation of functional capabilities and interface features. Information Technology and Libraries, 13 (3), 174–195.

Cibbarelli, P. (1996) Library automation alternatives in 1996 and user satisfaction ratings of library users by operating system. Computers in Libraries, 16 (2), 26–35.

Collier, M. W. (1997) A model for the electronic university library. In A. H. Helal and J. W. Weiss (eds), Toward a Worldwide Library: A Ten Year Forecast. Essen: Essen University Library.

Cousins, S. (1997) COPAC: new research library union catalogue. Electronic Library, 15 (3), 185–188.

Dempsey, L., Russell, R. and Kirriemuir, J. (1996) Towards distributed library systems: Z39.50 in a European context. Program, 30 (1), 1–22.

Electronic public information/one-stop shops/kiosks (1996) Vine, special issue (102).

Fletcher, M. (1996) The CATRIONA project: feasibility study and outcomes. Program, 30 (2), 99–107.

Furness, K. L. and Graham, M. E. (1996) The use of information technology in special libraries in the UK Program, 30 (1), 23–37.

Griffiths, J. M. and Kertis, K. (1994) Automated system marketplace. Library Journal, 119 (6), 50–59.

Grosch, A. N. (1995) Library Information Technologies and Networks. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Hanson, T. and Day, J. (1998) Managing the Electronic Library: A Practical Guide for Information Professionals. London : Bowker-Saur.

Keen, M. (1997) The OKAPI projects. Journal of Documentation, 53 (1), 84–87.

Lancaster, F. W. and Sandore, B.. (1997) Technology and Management in Library and Information Services. London: Library Association.

Leeves, J. (1995) Library systems then and now. Vine (100), September, 19–23.

Leeves, J. and Russell, R. (1995) Libsys.uk: a Directory of Library Systems in the United Kingdom. London: LITC, South Bank University.

Matthews, J. (1995) Moving to the next generation: Aston University’s selection and implementation of Galaxy 2000. Vine (101), December, 42–49.

Murray, I. R. (1997) Assessing the effect of new generation library management systems. Program, 31 (1–4), 313–327.

Robertson, S. E. (1997) Overview of Okapi projects. Journal of Documentation, 53 (1), 3–7.

Rowley, J. E. (1994) GENESIS: a new beginning or a new generation. Electronic Library, 12 (5), 277–283.

Stafford, J. (1996) Self issue the management implications. The introduction of self service at the University of Sunderland. Program, 30 (4), 375–383.

Tedd, L. A. (1995) An introduction to sharing resources via the Internet in academic library and information centres in Europe. Program, 29 (1), 43–61.

Wilson, M. (1994) Talis at Nene: an experience in migration in a college library. Program, 28 (3), 239–251.

Yeates, R. (1996) Library automation: the way forward? Program, 30 (3), 239–253.