Chapter 17

Synapse Formation

A fundamental issue in neurobiology is defining the mechanisms by which neurons form synapses with their targets. The development of appropriate synaptic connections requires a series of steps including the specification and generation of neurons and their target cells (Chapters 13, 14, and 15), the guidance of axons to their targets, the selection of appropriate targets, the formation of orderly and specific projections within the target (Chapter 16), and ultimately the induction of a specialized presynaptic terminal and postsynaptic membrane (this chapter). The first section of this chapter focuses on neuromuscular synapses that form between motor neurons and muscle cells in the peripheral nervous system. The second section summarizes current views of how neuron–neuron synapses in the central nervous system are assembled.

Development of the Neuromuscular Synapse

Once axons have arrived at their appropriate target destination, synapse formation ensues. Much of our understanding about the mechanisms of synapse formation arises from studies of the neuromuscular synapse. These studies have benefited from (1) the relative ease of experimentally manipulating developing and regenerating neuromuscular synapses in vivo, (2) cell culture systems for both motor neurons and skeletal muscle cells, (3) the Torpedo electric organ, an abundant and homogeneous source of neuromuscular-like synapses (Box 17.1), and (4) transgenic and mutant mice for studying and altering gene expression. Consequently, we have a good, although incomplete, understanding of the mechanisms that lead to the formation of the neuromuscular synapse.

Box 17.1 Torpedo Electric Organ

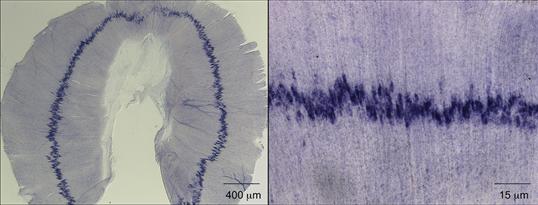

The majority of proteins known to be localized to neuromuscular synapses were first identified in postsynaptic membranes isolated from the electric organ of the marine ray Torpedo. Indeed, this specialized tissue has been essential for the identification and purification of AChR, AChE, Rapsyn, Syntrophin, Agrin, MuSK, and several synaptic vesicle proteins. The electric organ is a particularly homogeneous and abundant source of pre- and postsynaptic membranes that are similar in structure and function to those at neuromuscular synapses. The biochemical advantages of the electric organ are evident from its anatomy. The postsynaptic cell, which differentiates initially as a syncitial skeletal muscle fiber but subsequently loses its contractile machinery, is termed an electroplaque. Each electroplaque is a thin, elongated cell (1 cm × 1 cm × 10 μm) that is so densely innervated that nearly one-half of the electrocyte membrane is studded by nerve terminals. In contrast, nerve terminals occupy less than 0.1% of the cell surface of a skeletal myofiber. Because of this dense innervation and because the electric organ from a moderate size ray weighs several kilograms, it is possible to obtain several mg of purified postsynaptic proteins from a single electric organ.

Innervation is restricted to the ventral surface of the electroplaque, whereas the dorsal surface is enriched for the sodium/potassium ATPase that maintains the resting potential. Because the electroplaque lacks action potentials, activation of AChRs on the innervated ventral surface results in a voltage drop across the innervated but not the noninnervated membrane of the electrocyte. Since thousands of electroplaques are stacked closely one upon another, the potential difference across a single electrocyte is summated by the stack of electroplaques, resulting in a several thousand volt potential difference across the entire electric organ, a voltage that is sufficient to stun prey.

Steven J. Burden and Peter Scheiffele

The assembly of neuromuscular synapses is a multistep process. It requires coordinated interactions between motor neurons and muscle fibers, which eventually lead to the formation of a highly specialized postsynaptic membrane and a highly differentiated nerve terminal. As a consequence, acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) become highly concentrated in the postsynaptic membrane and arranged in perfect register with active zones in the presynaptic nerve terminal, ensuring fast, robust, and reliable synaptic transmission. Because neuromuscular synapses control all voluntary movement as well as respiration, the formation and function of this synapse are essential for survival. Disruption of this synapse, caused by axon withdrawal and motor neuron death, is responsible for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). A large number of proteins contribute to the process of synapse formation, several of which play fundamental roles: (1) Agrin, a motor neuron-derived ligand essential to stabilize nascent synapses; (2) Lrp4, the receptor for Agrin; (3) MuSK, the receptor tyrosine kinase that transduces the Agrin signal; (4) Dok-7, an adaptor protein that is recruited to activated MuSK; and (5) Rapsyn, the AChR-associated protein that anchors AChRs at synapses. Defects in this signaling pathway, which lead to a reduced number of AChRs at synapses, are responsible for a variety of congenital neuromuscular disorders, termed congenital myasthenia, and autoantibodies to AChRs, Lrp4 or MuSK are responsible for myasthenia gravis. Here, we describe the structure of the neuromuscular synapse and the molecules and mechanisms responsible to assemble this structure.

Substructural Organization of the Neuromuscular Synapse

An adult myofiber, a syncitial cell containing hundreds to thousands of nuclei, is innervated by a single motor axon that terminates and arborizes over approximately 0.1% of the muscle fiber’s cell surface. The neurotransmitter receptor, AChR, is highly concentrated in this small patch of the muscle fiber membrane, and its precise localization to synaptic sites during development is a hallmark of the inductive events of synapse formation. Although other proteins are likewise concentrated at synaptic sites, much of our knowledge about synaptic differentiation has come from studies designed to understand how AChRs accumulate at synaptic sites.

Nerve terminals are situated in shallow depressions of the muscle cell membrane, which is invaginated further into deep and regular folds, termed postjunctional folds (Fig. 17.1). AChRs and additional proteins (see later) are localized to the crests of these postjunctional folds, whereas other proteins, including sodium channels, are enriched in the troughs of the postjunctional folds. The nerve terminal likewise is organized spatially, and its substructural organization reflects that of the postsynaptic membrane. Synaptic vesicles are sparse in the region of the nerve terminal underlying Schwann cells, which cover nerve terminals and myelinate motor axons, and abundant in the region of the nerve terminal facing the muscle fiber. Moreover, synaptic vesicles are clustered adjacent to a poorly characterized specialization of the presynaptic membrane, termed active zones, which are the sites of synaptic vesicle fusion. Active zones are organized at regular intervals and are aligned precisely with the mouths of the postjunctional folds. This precise registration of active zones and postjunctional folds ensures that acetylcholine encounters a high concentration of AChRs within microseconds after release, thereby facilitating synaptic transmission. The alignment of structural specializations in pre- and postsynaptic membranes, separated by a 500-Å synaptic cleft, suggests that spatially restricted signaling between pre- and postsynaptic cells is important to coordinate pre- and postsynaptic differentiation. The mechanisms that align active zones and postjunctional folds are not well understood, but α3/β2 laminin, produced by the muscle and found in the synaptic basal lamina, binds calcium channels in nerve terminals, and this interaction has a role in anchoring active zones and coordinating pre- and postsynaptic differentiation (Nishimune, Sanes, & Carlson, 2004).

Figure 17.1 Pre- and postsynaptic membranes at the neuromuscular synapse are highly specialized. (A) An electron micrograph of a neuromuscular synapse shows that the nerve terminal is capped by a Schwann cell and is situated in a shallow depression of the muscle cell membrane, which is invaginated further into deep and regular folds, termed postjunctional folds (arrows). AChRs, labeled with α-bungarotoxin coupled to horseradish peroxidase, are concentrated at the synaptic site. (B) A higher magnification view shows that AChRs are concentrated at the crests and along the sides of the postjunctional folds (white arrow). Rapsyn, Neuregulin receptors, and MuSK are also concentrated in the postsynaptic membrane, whereas Agrin, Neuregulin-1, acetylcholinesterase, S-laminin, and certain isoforms of collagen are localized to the synaptic basal lamina. The postjunctional folds of the myofiber are spaced at regular intervals and are situated directly across from active zones and clusters of synaptic vesicles in the nerve terminal (arrows).

The precise organization of molecules in pre- and postsynaptic membranes belies the concept that the neuromuscular synapse is a simple synapse. Rather, the substructure of pre- and postsynaptic membranes, together with the faithful registration of pre- and postsynaptic specializations, suggests that complex mechanisms are required to assemble the synapse and to coordinate pre- and postsynaptic differentiation.

Muscle-Autonomous Patterning of AChR Expression

As motor axons extend toward developing muscle, muscle cells are themselves undergoing differentiation. Myotubes, formed by fusion of precursor myoblasts, develop prior to innervation and continue to grow after innervation by further myoblast fusion. Because myoblasts fuse to developing myotubes at their growing ends, the central region of the muscle is more mature than the distal ends of the muscle. Recent studies have shown that the central region of muscle is regionally specialized prior to innervation. For example, AChRs are already clustered in the central region of the muscle prior to and independent of innervation (Flanagan-Steet, Fox, Meyer, & Sanes, 2005; Lin et al., 2001; Panzer, Song, Balice-Gordon, 2006; Yang et al., 2001; Yang, Li, Prescott, Burden, & Wang, 2000;). As such, motor axons approach muscles that are regionally specialized, or prepatterned, prior to innervation, in a manner that preconfigures the prospective zone of innervation (Fig. 17.2).

Figure 17.2 Muscle prepatterning. (A) Motor axons (green) approach muscles that are prepatterned, as AChR transcription (blue) and AChR clustering (red) are enhanced in the central, prospective synaptic region of muscle, prior to and independent of innervation. Motor axons terminate and form synapses (orange) in the prepatterned region. (B) Lrp4 and MuSK are required for prepatterning AChRs and are themselves expressed in the central region of muscle independent of innervation. The prepatterned zone of AChR expression becomes refined and sharpened following innervation, so that AChR expression and AChR clustering are restricted to nascent synaptic sites. Two neural signals refine AChR expression: Agrin/MuSK signaling stabilizes and stimulates AChR clustering, whereas acetylcholine (ACh) disperses AChR clusters. As a consequence of these two signals, AChR clusters are maintained only at nascent synaptic sites.

How the prospective synaptic region of the muscle becomes prepatterned is not well understood (see following), but muscle prepatterning restricts motor axon growth and promotes synapse formation in the central region of mammalian muscle (Kim & Burden, 2008).

The Synaptic Basal Lamina Contains Signals for Synaptic Differentiation

Following contact with the growth cone of a developing motor neuron, developing muscle fibers undergo a complex differentiation program in the synaptic region, which is dependent upon motor neuron–derived signals. In addition, signals from the muscle regulate differentiation of presynaptic nerve terminals. The idea that signals for regulating both presynaptic and postsynaptic differentiation are contained in the synaptic basal lamina arose from studies of regenerating neuromuscular synapses. Following damage to a motor axon, the distal portion of the motor axon degenerates, and the proximal end regenerates to muscle. The regenerated axon precisely reinnervates the original synaptic site and forms a synapse that is indistinguishable from the original synapse. Original synaptic sites are not thought to provide guidance cues to motor axons; rather, it is believed that the vacated perineural tubes, containing Schwann cells and their basal lamina, provide a favorable substrate for motor axons and have a role in directing regenerating motor axons to original synaptic sites (Son & Thompson, 1995). Although motor axons precisely reinnervate original synaptic sites, there appears to be little, if any, selectivity among motor neurons or among Schwann cells in ensuring accurate regeneration; indeed, both original and foreign motor neurons can accurately and functionally reinnervate original synaptic sites in denervated muscle.

Following damage to motor axons and muscle, nerve terminals and muscle fibers degenerate and are phagocytized, but the basal lamina of the muscle fiber remains intact. Even in the absence of nerve terminals and muscle fibers, several structures, including the terminal Schwann cells, the basal lamina of the postjunctional folds, and AChE, remain at the original synaptic site and allow for its identification.

Axons eventually regenerate into the muscle, and new myofibers regenerate within the basal lamina of the original myofiber. The regenerated motor axons form synapses with the regenerated myofibers precisely at the original synaptic sites. If axons regenerate into muscle, but muscle regeneration is prevented, axons still unerringly reinnervate the original synaptic site on the basal lamina, and active zones form in register with the basal lamina of the original postjunctional folds (Fig. 17.3) (Sanes, Marshall, & McMahan, 1978). Thus, the presence of the myofiber is necessary neither for precise reinnervation nor for the morphological differentiation of regenerated nerve terminals. The vacated perineurial tubes, containing Schwann cells and their basal lamina, may direct regenerating motor axons to original synaptic sites, but the induction of active zones suggests that cues in the synaptic basal lamina, possibly α3/β2 laminin, have a role in organizing the presynaptic terminal.

Figure 17.3 The synaptic basal lamina contains signals for presynaptic and postsynaptic differentiation. A cross section of normal muscle containing a nerve terminal, Schwann cell, and myofiber is shown at the far left. AChR genes are induced in synaptic nuclei (red) and AChRs (green) are concentrated at synaptic sites. Active zones and clusters of synaptic vesicles in the nerve terminal are aligned with postjunctional folds in the myofiber. Each myofiber is ensheathed by a basal lamina (MBL), which is specialized at the synaptic site (synaptic BL) and which remains intact following degeneration of the original myofiber. The MBL serves as a scaffold for regenerating myofibers, which form from the fusion of satellite cells that proliferate following damage to the original myofiber. (A) Experiments showing that the synaptic basal lamina contains signals for clustering AChRs and activating AChR genes in synaptic nuclei. Following damage and degeneration of axons, Schwann cells, and myofibers, new myofibers regenerate within the basal lamina of the original myofiber in the absence of the nerve. AChRs cluster and AChR gene expression is reinduced at original synaptic sites in myofibers that regenerate in the absence of the nerve and other original presynaptic cells. (B) Experiments showing that the synaptic basal lamina contains signals for inducing presynaptic differentiation. Following damage and degeneration of axons and myofibers, motor axons regenerate to original synaptic sites in the absence of the myofiber and accumulate synaptic vesicles precisely across from the sites of the original postjunctional folds.

If regeneration of motor axons is prevented, but myofibers are allowed to regenerate, AChRs accumulate and membrane folds form in the regenerated myofiber precisely at the original synaptic site on the basal lamina (Burden, Sargent, & McMahan, 1979). Thus, in the absence of nerve terminals, myofibers, and terminal Schwann cells, information remains at the original synaptic site and instructs both pre- and postsynaptic differentiation (Fig. 17.3). Because the synaptic basal lamina is the most prominent extracellular structure remaining at neuromuscular synapses following removal of all cells, these results indicate that the synaptic basal lamina contains signals that can induce differentiation of both nerve terminals and myofibers.

Agrin is a Signal for Postsynaptic Differentiation

Because clustering of AChRs, unlike the formation of active zones, can be studied readily in cell culture, it has been far simpler to identify the basal lamina signals that induce postsynaptic rather than presynaptic differentiation. Extracellular matrix from the Torpedo electric organ, a tissue that is homologous to muscle but more densely innervated, contains an activity that stimulates AChR clustering in cultured myotubes (see Box 17.1). McMahan and colleagues purified the electric organ activity, which they termed Agrin, and showed that Agrin is synthesized by motor neurons, transported in motor axons to synaptic sites, and deposited in the synaptic basal lamina. Agrin also stimulates the clustering of other synaptic proteins, including AChE, Rapsyn, and Utrophin (see later), indicating that Agrin has a central role in synaptic differentiation.

Agrin is a ~200-kDa protein containing multiple epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like signaling domains, two different laminin-like domains, and multiple follistatin-like repeats. The four EGF-like domains and three laminin G domains are contained in the carboxyl-terminal region, which is sufficient for inducing AChR clusters in cultured myotubes; sequences in the amino-terminal region are responsible for the association of Agrin with the extracellular matrix.

The agrin gene is expressed in a variety of cell types. Alternative splicing results in multiple Agrin isoforms that differ in their AChR clustering efficiency. The isoform that is most active in clustering AChRs is expressed in neurons, including motor neurons, whereas other Agrin isoforms are expressed in additional cell types, including skeletal muscle cells. The active, neuronal-specific isoforms of Agrin contain 8, 11, or 19 amino acids at a splice site, referred to as the Z site in rat Agrin and the B site in chick Agrin. The agrin gene contains multiple promoters. Although the promoter used in motor neurons leads to expression of isoforms that are associated with the extracellular matrix, the promoter used in the CNS leads to expression of membrane-bound isoforms (Burgess, Skarnes, & Sanes, 2000).

In mice lacking Agrin, AChRs are initially prepatterned, and synapses appear to form, but only transiently (Lin et al., 2001; Misgeld, Kummer, Lichtman, & Sanes, 2005). Over the course of several days, the AChR prepattern is dispersed, synapses are lost, and motor axons begin to grow throughout the muscle. Thus, Agrin is necessary to stabilize the AChR prepattern and nascent synapses. Because the AChR prepattern is stable in the absence of innervation but dispersed by motor axons lacking Agrin, neural signals, other than Agrin, extinguish the AChR prepattern (Lin et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001). Genetic evidence indicates that acetylcholine is a key neural signal that disperses AChR clusters (Lin et al., 2005; Misgeld et al., 2005). Thus, during normal development, Agrin counteracts acetylcholine-mediated dispersion, thereby stabilizing AChR clusters selectively at nascent synapses (see following).

MuSK and Lrp4 Are Required for Agrin-Mediated Signaling and Synapse Formation

The mechanisms of Agrin-mediated AChR clustering are poorly understood, but a receptor tyrosine kinase, termed MuSK, is a critical component of an Agrin receptor complex. MuSK is expressed in Torpedo electric organ and in skeletal muscle, where it is concentrated in the postsynaptic membrane (Jennings, Dyer, & Burden, 1993; Valenzuela et al., 1995). Mice deficient in MuSK (DeChiara et al., 1996), like agrin mutant mice, lack normal neuromuscular synapses. Both agrin and MuSK mutant mice are immobile, cannot breathe, and die at birth. Muscle differentiation is normal in agrin and MuSK mutant mice, but muscle fibers in MuSK mutant mice lack all known features of postsynaptic differentiation. Moreover, unlike agrin mutant mice, the AChR prepattern is absent from MuSK mutant mice at all stages, indicating that MuSK is essential not only for synapse formation but also to establish muscle prepatterning. Muscle-derived proteins, including AChRs and AChE, which are concentrated at synapses in normal mice, are distributed uniformly in MuSK mutant myofibers (Fig. 17.4). In addition, AChR genes, which are transcribed selectively in synaptic nuclei of normal muscle fibers (see later), are transcribed at similar rates in synaptic and nonsynaptic nuclei of muscle fibers from MuSK mutant mice.

Figure 17.4 Presynaptic and postsynaptic differentiation are defective in mice lacking MuSK. Whole mounts of muscle from wild-type and MuSK mutant mice were stained with antibodies to neurofilament (NF) and synaptophysin (Syn) to label motor axons and nerve terminals (green), respectively, and with α-bungarotoxin to label acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) (red). In MuSK mutant mice, motor axons fail to stop and differentiate adjacent to the main intramuscular nerve and instead wander aimlessly over the muscle; AChRs, as well as other postsynaptic proteins, are expressed at normal levels but they fail to cluster.

Multiple lines of evidence indicate that MuSK is required for Agrin-mediated signaling and is a component of an Agrin receptor complex (Glass et al., 1996): (1) Agrin can be chemically cross-linked to MuSK in cultured myotubes; (2) Agrin induces rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of MuSK in cultured myotubes; (3) a recombinant, soluble extracellular fragment of MuSK inhibits Agrin-induced AChR clustering in cultured muscle cells; (4) cultured MuSK mutant muscle cells, unlike normal muscle cells, do not cluster AChRs in response to Agrin; and (5) dominant-negative forms of MuSK inhibit Agrin-induced AChR clustering in cultured myotubes. MuSK itself, however, does not bind Agrin (Glass et al., 1996).

Instead, the muscle receptor for Agrin is the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (Lrp4) (Kim et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). Neural Agrin binds Lrp4, which stimulates association between Lrp4 and MuSK and increases MuSK kinase activity (Kim et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). Only neural forms of Agrin bind Lrp4, providing an explanation for the selective activation of MuSK by neural isoforms of Agrin (Kim et al., 2008). Because Lrp4 self associates, independent of Agrin, Agrin may increase MuSK kinase activity by stimulating recruitment of MuSK to a preformed oligomer of Lrp4, thereby facilitating MuSK trans-phosphorylation. Lrp4 is essential for synapse formation, and the synaptic defects in lrp4 mutant mice appear identical to those in MuSK mutant mice (Weatherbee, Anderson, & Niswander, 2006).

Interestingly, a pair of proteins with homology to MuSK and Lrp4 are required for clustering AChRs at C. elegans neuromuscular synapses: CAM-1, a receptor tyrosine kinase that shares homology with MuSK, and LEV-10, a transmembrane protein that contains an LDLa domain and forms a complex with two secreted proteins, LEV-9 and OIG-4, as well as AChRs (Francis et al., 2005; Gally, Eimer, Richmond, & Bessereau, 2004; Rapti, Richmond, & Bessereau, 2011). However, the kinase activity of CAM-1 is dispensable for synaptic differentiation, pointing to a different mechanism of action than MuSK at vertebrate neuromuscular synapses.

Glutamate, rather than ACh, is the neurotransmitter at Drosophila neuromuscular synapses. As such, perhaps it is not surprising that a different class of signals regulate differentiation of these synapses. Although little is known about the initial formation of synapses during embryogenesis in Drosophila, two ligands, Wingless and TGF-β, unrelated to Agrin, are involved in the growth of Drosophila neuromuscular synapses during larval development. Wingless is secreted by motor neurons and thought to activate Frizzled-2, a Wingless receptor expressed in muscle (Packard et al., 2002), whereas Glass bottom boat, a ligand from the TGF-β family, is synthesized by muscle and thought to activate Wishful thinking, a type II receptor, in motor neurons (Aberle et al., 2002). These signaling mechanisms participate in the regulation of bouton growth and size, which adapt to changes in synaptic activity.

Downstream of MuSK

How does MuSK activation lead to postsynaptic differentiation at vertebrate neuromuscular synapses? Agrin binds Lrp4 and stimulates the rapid phosphorylation of MuSK. The kinase activity of MuSK is essential for Agrin to stimulate clustering and tyrosine phosphorylation of AChRs. Signaling downstream from MuSK depends on phosphorylation of a tyrosine residue (Y553) in the juxtamembrane region of MuSK (Herbst, Avetisova, & Burden, 2002). Phosphorylation of this tyrosine leads to recruitment of Dok-7 (Okada et al., 2006), an adapter protein that further stimulates MuSK and becomes tyrosine phosphorylated (Bergamin, Hallock, Burden, & Hubbard, 2010). Mice lacking Dok-7 have defects identical to MuSK mutant mice (Okada et al., 2006), and mutations in human Dok-7 are a major cause of congenital myasthenia (Beeson et al., 2006). Tyrosine phosphorylated Dok-7 recruits Crk and Crk-L, two related adapter proteins that engage additional but unknown downstream signaling pathways essential for synapse formation (Hallock et al., 2010). Rac and Rho, small GTP-binding proteins that regulate actin organization, are activated by Agrin and required for Agrin to stimulate AChR clustering (Weston, Yee, Hod, & Prices, 2000; Weston et al., 2003). Rac acts early and is important for the formation of AChR microclusters, whereas Rho is activated more slowly and is important for the consolidation of microclusters into larger AChR clusters. Moreover, at least one kinase acts downstream from MuSK and is recruited and/or activated by Agrin-activated MuSK, as staurosporine, a protein kinase inhibitor, inhibits Agrin-induced AChR tyrosine phosphorylation and clustering without blocking tyrosine phosphorylation of MuSK. Figure 17.5 illustrates the fundamental signaling components required for forming neuromuscular synapses.

Figure 17.5 Signaling mechanisms for neuromuscular synapse formation. Agrin, released from motor axon terminals, binds Lrp4, stimulating association between Lrp4 and MuSK and increasing MuSK kinase activity. Phosphorylation of MuSK Y553, in the MuSK juxtamembrane region, causes recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of Dok-7, which further stimulates MuSK and recruits Crk and Crk-L adapter proteins to the MuSK/Dok-7 signaling complex. Rac and Rho GTPases function downstream of MuSK/Dok-7/Crk/Crk-L to anchor AChRs at synapses by a poorly understood process that requires Rapsyn, which binds directly to AChRs. The pathway for synapse-specific transcription is less well understood but likely involves JNK-dependent activation of Ets-family transcription factors that stimulate expression of multiple genes encoding synaptic proteins. Synaptic vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane of the nerve terminal, releasing acetylcholine (ACh), which binds to AChRs and causes a conformational change that increases the permeability of the channel to small cations and depolarizes the muscle.

Synapses gradually mature after their initial formation and become fully mature and stable nearly one month after birth in mice. The mechanisms involved in this transition are not well understood, but may involved additional signaling molecules, such as Neuregulin and ErbB receptors, as well as Src-family kinases and cytoskeletal components, such as dystrobrevin (Grady et al., 2000; Smith, Mittaud, Prescott, Fuhrer, & Burden, 2001).

Muscle-Autonomous and Neural-Dependent Patterning of AChR Expression

The preceding sections have described the role of muscle prepatterning and motor neuron-derived signals in regulating the distribution of AChR expression. An initial, spatially restricted pattern of AChR expression is generated in muscle independent of neurally derived Agrin, or indeed of any other neural signal (Fig. 17.2). The mechanisms that are intrinsic to muscle and responsible for establishing regional differences in muscle in the absence of innervation are not well understood but appear to depend upon the pattern of muscle growth and positive feedback loops that sustain MuSK activation (Kim & Burden, 2008). Because this prepattern is not observed in mice lacking Lrp4, MuSK, or Dok-7, the emergence of this muscle AChR prepattern, nonetheless, coopts some of the same molecules used later during normal synaptogenesis. Additional molecules, however, may be dedicated for prepatterning; for example, zebrafish Wnt11R can function as an alternative direct ligand for MuSK and is important for prepatterning but not synapse formation in zebrafish (Jing, Lefebvre, Gordon, Granato, 2009). Whether Wnts have a role in prepatterning mammalian muscle is not known.

The prepatterned region specifies where motor axons will form synapses. Some synapses form on prepatterned AChR clusters, which become stabilized by Agrin, whereas Agrin also induces new AChR clusters (Flanagan-Steet et al., 2005; Panzer et al., 2006). Thus, the final cohort of synapses on the muscle fiber includes those recognized by motor axons and those induced by motor axons (Arber, Burden, & Harris, 2002; Kummer, Misgeld, & Sanes, 2006) (Fig. 17.2).

Arrival of the nerve, and its attendant signals, converts the AChR prepattern into the more refined pattern of AChR transcription and AChR clustering characteristic of mature synapses. This conversion appears to be dependent on two separable nerve-dependent programs: one program utilizes neurally derived Agrin to maintain AChR expression at nascent synaptic sites, and a second program, which appears to be triggered by acetylcholine, extinguishes AChR clustering at sites that are not stabilized by Agrin/MuSK signaling (Fig. 17.2). These two programs thus ensure the stable expression of AChR clusters selectively at nascent synapses.

Rapsyn is Required for Postsynaptic Differentiation Downstream of Agrin and MuSK

A 43-kDa protein, termed Rapsyn, has an important role in Agrin-mediated signaling. Rapsyn is a myristolated, peripheral membrane protein that is present at 1:1 stoichiometry with AChRs at synaptic sites and interacts directly with AChRs. In addition, Rapsyn links AChRs to components of a subsynaptic, cytoskeletal complex, including Dystroglycan and Dystrophin, Utrophin, Syntrophin, Dystrobrevin, and α-actinin.

Agrin stimulates the clustering of Rapsyn in myotubes grown in cell culture, and clustering of Rapsyn and AChRs occurs coincidentally at developing synapses. Rapsyn is critical for synapse formation, since mice lacking Rapsyn die within hours after birth and have difficulty moving and breathing (Gautam et al., 1995). Mutations in human Rapsyn are a cause of congenital myasthenia with defects in AChR clustering that lead to muscle weakness (Engel, Ohno, & Sine, 2003). Although the mechanisms by which Rapsyn regulates the clustering of synaptic proteins are poorly understood, the clustering of most synaptic proteins, including AChRs, Utrophin, and Dystroglycan, depends upon Rapsyn. Nonetheless, MuSK is clustered at synapses in rapsyn mutant mice, raising the possibility that engagement with Agrin/Lrp4 is sufficient to stabilize MuSK at rapsyn mutant synapses. Synapse-specific gene expression (see following) is also normal in rapsyn mutant mice, indicating that Rapsyn acts downstream from MuSK to anchor postsynaptic proteins but not in the synapse-specific transcription pathway.

Agrin and MuSK Are Required for Retrograde Signaling and Presynaptic Differentiation

Although pathfinding of motor axons to muscle is normal in mice lacking Agrin or MuSK, agrin and MuSK mutant mice lack normal nerve terminals. In the mutant mice, branches of the main intramuscular nerve fail to arrest their growth and instead wander aimlessly across the muscle (Fig. 17.4). Because MuSK is expressed in skeletal muscle and not in motor neurons, it seems likely that the aberrant behavior of presynaptic terminals in MuSK mutant mice is due to indirect actions of the Agrin/MuSK signaling system. Indeed, restoring MuSK expression selectively in muscle of MuSK mutant mice rescues synapse formation and neonatal lethality (Herbst et al., 2002). These results indicate that Agrin, released from nerve terminals, causes the muscle cell, via MuSK activation, to reciprocally provide a recognition signal back to the nerve to indicate that a functional contact has occurred. In response to this putative muscle-derived recognition or adhesion signal, the nerve undergoes presynaptic differentiation and stops growing. Unlike our knowledge of the signals and mechanisms that control postsynaptic differentiation, unraveling the mechanisms that control the differentiation of motor nerve terminals has proved far more challenging and remains one of the glaring gaps in our understanding of neuromuscular synapses. Several muscle-derived signals regulate distinct aspects of presynaptic differentiation: FGFs of the 7/10/22 subfamily, laminin β2, collagen IV, and SIRP-α stimulate clustering of synaptic vesicles in cultured motor neurons. Genetic studies support the idea that these signals participate in synaptic differentiation, since neuromuscular synapses do not fully mature in mice that are mutant for FGFR2, laminin β2, or collagen IV alpha subunits (Fox et al., 2007). Nonetheless, motor axons terminate and differentiate to a considerable extent in the absence of these signaling components, indicating that additional, yet to be identified retrograde organizers regulate earlier steps in presynaptic differentiation.

Certain Genes Are Expressed Selectively in Synaptic Nuclei of Myofibers

Like AChR protein, mRNAs encoding the different AChR subunits (α, β, γ or ε and δ) are concentrated at synaptic sites. Studies with transgenic mice that harbor gene fusions between regulatory regions of AChR subunit genes and reporter genes have shown that AChR genes are transcribed selectively in myofiber nuclei near the synaptic site (Fig. 17.6). Thus, localized transcription of AChR genes in synaptic nuclei is responsible, at least in part, for the accumulation of AChR mRNA at synaptic sites. This pathway is important for ensuring that AChRs are expressed at the required density in the postsynaptic membrane, since defects in synapse-specific gene expression of the AChR ε subunit gene are a cause for congenital myasthenia (see later).

Figure 17.6 Acetylcholine receptor (AChR) genes are expressed selectively by myofiber synaptic nuclei, leading to enrichment of AChR mRNA in the central, synaptic region of the muscle. A whole mount of a mouse diaphragm muscle was processed for in situ hybridization to reveal the pattern of AChR δ mRNA expression. AChR δ mRNA expression is concentrated in a narrow band in the central, synaptic region of the muscle.

Like AChR subunit genes, the utrophin gene is transcribed selectively in synaptic nuclei, resulting in an accumulation of utrophin mRNA and protein at synaptic sites. mRNAs encoding Rapsyn, NCAM, MuSK, sodium channels, the catalytic subunit of AChE, LL5beta, and CD24 are also concentrated in the synaptic region of skeletal myofibers, raising the possibility that these genes are likewise transcribed preferentially in synaptic nuclei (Fig. 17.5). Thus, synapse-specific transcription may be a common and important mechanism for expressing and localizing a variety of gene products at high levels at the neuromuscular synapse.

The neural signals that regulate synapse-specific transcription remain elusive. Neuregulin-1, which stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB2, a member of the EGF receptor family, stimulates AChR gene expression in cultured muscle cells, but neuromuscular synapses form normally during development in mice lacking ErbBs in skeletal muscle, as well as in mice lacking Neuregulin-1 in motor neurons and skeletal muscle (Escher et al., 2005; Jaworski & Burden, 2006). Synapse-specific transcription in vivo, however, requires Agrin, Lrp4, and MuSK, indicating that this signaling pathway has a critical role in regulating synaptic gene expression.

Ets Domain Transcription Factors Regulate Synapse-Specific Transcription

A binding site for Ets domain proteins in the AChR delta subunit gene is critical for synapse-specific gene expression in mice. Importantly, mutation of an Ets-binding site in the human AChR ε subunit gene leads to congenital myasthenia, due to decreased AChR expression. This Ets site can bind GABP, a complex containing GABPα, an Ets protein, and GABPβ, a protein that lacks an Ets domain but dimerizes with GABPα, suggesting that GABP may be a transcriptional regulator that stimulates transcription of AChR genes in synaptic nuclei (Fig. 17.5). In addition, the gene encoding another Ets domain protein, Erm, is expressed selectively by myofiber synaptic nuclei (Hippenmeyer et al., 2002), suggesting that Erm may also have a role in synapse-specific expression. Genetic analysis of GABP and erm mutant mice indicates that Erm has a critical role, whereas GABP has a more subsidiary role in synapse-specific transcription.

Electrical Activity Regulates Gene Expression

Changes in the pattern of muscle electrical activity have an important role in regulating the electrophysiological and structural properties of muscle, as well as the ability of motor axons to innervate muscle. The expression of several genes, including AChR genes, is repressed by electrical activity, and this repression, together with focal activation in synaptic nuclei, as described earlier, contributes to the disparate levels of AChR expression in synaptic and nonsynaptic regions of the muscle. A binding site for myogenic bHLH transcription factors, or E box, in the proximal promoter of AChR subunit genes is essential for electrical activity-dependent transcription, since transgenes containing a mutation in this E box, unlike wild-type transgenes, are not induced following denervation. These results suggest that electrical activity decreases the level and/or activity of E box binding proteins, notably Myogenin, leading to decreased AChR expression. The transcriptional mechanisms that control expression of myogenin in an activity-dependent manner are just beginning to be explored. Electrical activity induces expression of two transcriptional repressors, HDAC-9 (aka MITR) and Dach2, which act to repress myogenin expression (Mejat et al., 2005; Tang and Goldman 2006). A reduction in myofiber electrical activity leads to a reduction in HDAC-9 and Dach2 expression, causing an elevation in myogenin expression. Thus, the mechanisms that couple changes in electrical activity to changes in HDAC-9 and Dach2 expression are critical for regulating genes, such as AChR genes, which are dependent upon Myogenin. The mechanisms that regulate HDAC-9 and Dach2 expression are not understood, but the involvement of multiple protein kinases, including PKA, CAM kinase II, and PKC, has been suggested.

Summary

Signals exchanged at developing synapses ensure that differentiated presynaptic terminals are aligned precisely with a highly specialized postsynaptic membrane. Analysis of mice lacking innervation demonstrates that a coarse pattern of postsynaptic differentiation is present prior to innervation and that neuronal signals, including Agrin, both maintain and induce postsynaptic differentiation at sites of nerve–muscle contact (Fig. 17.2). We are gaining a better understanding of the pathways that act downstream from MuSK to control postsynaptic differentiation (Fig. 17.5), but we remain poorly informed about the signals and pathways that control presynaptic differentiation.

Synapse Formation in the Central Nervous System

Compared to synapse formation between neurons and muscle cells (at the neuromuscular synapse), we currently know relatively little about how neuron-to-neuron synapses in the central nervous system are put together. The reason for this relative lack of knowledge is the complexity of the problem. CNS synapses are much smaller (about one-hundredth the size of a neuromuscular synapse), a single neuron typically receives hundreds to thousands of synapses, and the synaptic inputs are derived from multiple different synaptic partners. Finally, these synapses employ not just one type but a variety of neurotransmitters. Some of these neurotransmitters are excitatory and depolarize the postsynaptic partner, and some are inhibitory and lead to hyperpolarization. The placement of excitatory and inhibitory synapses on the postsynaptic cell is a critical parameter for integration of these counteracting inputs. Synaptic connectivity in the CNS is not static but undergoes extensive plastic changes. In response to experience, synaptic connections and the function of neuronal circuits are modified. All of these CNS synapse properties pose intriguing questions regarding the synthesis of synaptic components, their targeting and assembly at functionally distinct synaptic sites, and the recognition of the appropriate synaptic partners amongst an array of candidate partners.

Despite these differences between peripheral and CNS synapses, there are several common principles that apply to both systems: (1) Like neuromuscular synapses, CNS synapses are tri-partite structures. Highly specialized presynaptic release sites are closely apposed to postsynaptic specializations that concentrate neurotransmitter receptors (Fig. 17.7). This pair of synaptic partners is lined by astroglial processes that ensheath the synaptic cleft. (2) Cells contain most synaptic proteins before synapse formation and bidirectional signaling organizes these components at emerging synaptic contacts. (3) Synapses undergo extensive functional maturation. (4) During development, an exuberant number of synaptic contacts are formed, some of which later undergo elimination.

Figure 17.7 Synapses are tripartite junctions. The electron micrograph shows a parallel fiber synapse in the mouse cerebellum, an example of a glutamatergic synapse. The presynaptic terminal contains a mitochondrion and clusters of synaptic vesicles throughout the terminal. A few vesicles are morphologically docked at the active zone opposite the postsynaptic density. The postsynaptic side is a dendritic spine that in the cross section appears like a circular structure. The electron-dense material opposite the vesicle release sites is the postsynaptic density (PSD). Synaptic cleft and dendritic spine are closely ensheathed by an astroglia process (image courtesy of Stéphane Baudouin).

The following section focuses on the formation of CNS synapses in vertebrates. Much research has been on glutamatergic synapses—excitatory synapses using the neurotransmitter glutamate that are the most abundant in the CNS. We will also highlight important insights gained in the analysis of synapses using other neurotransmitters. We will start by discussing the time-course of morphological rearrangements of synapse formation and then examine emerging evidence on the mechanisms controlling recruitment and assembly of pre- and postsynaptic components. Finally, we will describe some candidate signals that may contribute to the selectivity of synaptic wiring during development.

Initiation of Axon-Target Interaction

Prior to synapse formation, neurons already express both pre- and postsynaptic proteins. For example, growing axons and growth cones contain synaptic vesicles and release neurotransmitter. Similarly, target cells (that will later become the postsynaptic side) express functional neurotransmitter receptors on their surface. Cell–cell contact then is essential for the concentration and juxtaposition of pre- and postsynaptic components in opposing membranes and for achieving the mature complement of both pre- and postsynaptic proteins.

Many initial contacts between synaptic partners are established through filopodia, tiny actin-based extensions that rapidly protrude and retract from a cell. Importantly, filopodia extend from both axons and dendrites and increase the extracellular space sampled by a cell during development. Imaging studies, both in culture and in vivo, indicate that when filopodia contact potential synaptic partners, they can lose their motility and become stabilized. These contacts are then thought to transform into synaptic structures. Indeed, synaptic specializations have been seen on filopodia themselves, and neurotransmitter release from axons is likely to play an important role for the regulation of filopodial dynamics.

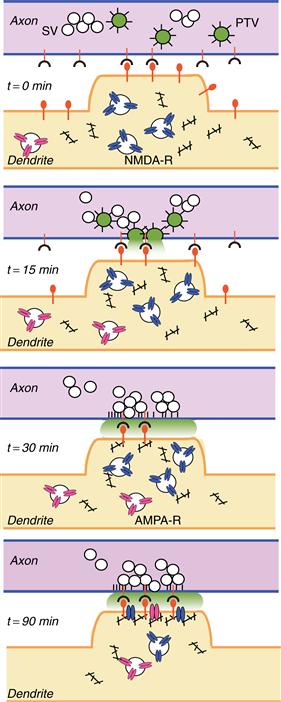

A further important realization from imaging studies has been that the assembly of synaptic structures occurs rapidly. The time required from initial contact to establishment of a functional synapse is only in the range of 1–2 hours, with the formation of a presynaptic terminal occurring in only 10–20 minutes and the recruitment of postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors taking place in approximately 90 minutes after cell–cell contact (Garner, Zhai, Gundelfinger, & Ziv, 2002). How is the entire machinery for regulated vesicular release recruited within such a short time frame? This timecourse is plausible if one considers that most synaptic components are “ready-to-go” before contact and primarily need to be redistributed (rather than newly synthesized). Still, the speed of synaptic assembly is remarkable. One intriguing model poses that presynaptic components are recruited in preassembled units (Fig. 17.8). Synaptic vesicles move in axons before synapse formation in grape-like clusters. Similarly, multiple active zone components such as voltage-gated calcium channels and syntaxin can be found prepackaged in so-called “piccolo-bassoon transport vesicles” (PTVs) (Garner et al., 2002). PTVs are vesicles named after the presynaptic active zone proteins piccolo and bassoon that are closely associated with these carriers that appear as 80-nm-diameter dense core vesicles in electron microscopy. PTVs could be rapidly captured and inserted in response to a target-derived signal, thereby greatly simplifying the process of presynaptic assembly (Fig. 17.8). Subsequently, neurotransmitter receptors are recruited to the postsynaptic domain. Excitatory synapses using the transmitter glutamate contain the ionotropic NMDA- and AMPA-type receptors (see Chapter 9). After cell–cell contact, NMDA- and AMPA-receptors are recruited to synapses in a stepwise manner, with an initial accumulation of NMDA receptors at postsynaptic sites and the subsequent addition of AMPA receptors (Fig. 17.8). Candidate signals for the neurotransmitter receptor accumulation at synapses and for the stabilization of filopodial contacts between pre- and postsynaptic partners are discussed next.

Figure 17.8 Hypothetical model for the assembly of central synapses. Before synapses formation, axons and dendrites contain synaptic vesicles (SV), active zone components, and neurotransmitter receptors, respectively. Cell–cell contact is initiated via cell surface adhesion and/or signaling molecules (red, t = 0 min). Contact triggers fusion of piccolo-bassoon transport vesicles (PTV, green) with the plasma membrane (t = 15 min), which leads to the deposition of active zone material (black spikes). Subsequently, synaptic vesicles (clear circles) are recruited to the cell–cell contact sites (t = 30 min), and postsynaptic scaffolding molecules (black), NMDA-type (blue), and AMPA-type neurotransmitter receptors (red) are delivered sequentially to the maturing postsynaptic membrane. Adapted from Garner et al. (2002).

Molecular Signals for Synaptic Development in the CNS

What are the signals that mediate the morphological and functional differentiation of pre- and postsynaptic structures? It turns out that several transsynaptic signals “singlehandedly” induce a substantial degree of synaptic organization. Based on this ability to drive synapse assembly, these signals have been termed “synapse-organizing” or “synaptogenic” factors. Synaptogenic proteins are employed in multiple ways to drive synapse organization: First, target cells (the future postsynaptic partner) secrete growth factors that instruct presynaptic differentiation in axons. We refer to these signals as retrograde organizers of synapses. Second, axons (the future presynaptic partner) release signals that drive the postsynaptic accumulation of neurotransmitter receptors, much like Agrin at the neuromuscular junction. These signals are referred to as anterograde organizers. Third, several adhesion and signaling complexes bridge the synaptic cleft and simultaneously recruit pre- and postsynaptic components; consequently, these are considered bidirectional organizers of synapses. Finally, synaptic astroglia also contribute signals that promote formation and maturation of central synapses. Examples for each of these four different classes of synapse-organizing mechanisms are discussed following.

Morphogens as Retrograde Signals for Synaptic Organization

Morphogens are secreted growth factors that direct cell fate decisions during embryonic development. Components of many morphogen signaling cascades continue to be expressed in the postnatal brain, indicating that they may govern additional developmental processes after the completion of cell fate specification. For example, Wnts and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) exhibit important, previously unanticipated signaling functions in axon guidance and synapse formation—essentially being “recycled” for morphogenetic programs in a different developmental context during postnatal development.

At CNS synapses, Wnts and FGFs both act as retrograde signals. This means they are released from synaptic target cells and promote presynaptic differentiation in afferents. Synaptic signaling functions were first discovered in the mouse cerebellum for Wnt7a, a vertebrate homologue of the Drosophila melanogaster wingless gene (Fig. 17.9). Wnt7a is released from cerebellar granule cells and promotes synaptic vesicle accumulation in mossy fiber axons, a class of afferent projections derived from the brainstem and the spinal cord (Hall, Lucas, & Salinas, 2000). Presynaptic vesicle recruitment in response to Wnt7a is most likely regulated through local modification of microtubule branching and remodeling. Wnt7a signaling is mediated through the axonal receptor frizzled, a receptor that also plays a central role in Wnt signaling during early development. Frizzled acts through the signaling adapter disheveled-1 (Dvl-1) and the cytoplasmic serine/threonine kinase GSK3beta. In turn, GSK3beta regulates microtubule-associated proteins (MAP1B and adenoma polyposis complex, APC) by phosphorylation to shape a specialized microtubule network in growth cones and axonal branches.

Figure 17.9 Synapse-organizing signals at CNS synapses. Different modes of synaptic organizing signals exchanged between pre- and postsynaptic partners and glial cells are illustrated. Wnt7a and FGF22 are retrograde signals derived from the postsynaptic target cell. Transsynaptic adhesion complexes link to scaffolding molecules which interact with presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) or postsynaptic NMDA-receptors (GluN1/N2), respectively. Several anterograde signals from the presynaptic cell exert their synapse-organizing functions via direct interaction with the amino-terminal-domain (NTD) of glutamate receptors. Perisynaptic astroglia release synapse-organizing molecules such as thrombospondin (TSP). See text for further discussion.

Fibroblast growth factors comprise a large family of secreted growth factors expressed in neuronal and nonneuronal cells. The closely related isoforms FGF22, FGF7, and FGF10 are target-derived signals that contribute to presynaptic development (Umemori, Linhoff, Ornitz, & Sanes, 2004). In the absence of FGF-signaling presynaptic vesicle accumulation in axons is reduced. Notably, neither Wnts nor FGFs organize the assembly of active zones, indicating that they preferentially promote the expansion of the presynaptic vesicle pools. FGF signaling is mediated through an axonal FGF receptor complex, a receptor tyrosine kinase that couples to the PI3-kinase and Ras-MAP-kinase pathway. Similar to Wnt7a, FGFs alter cytoskeletal properties and promote axonal branching. These morphological rearrangements shape the presynaptic partner and facilitate the recruitment of appropriate organelles in response to additional transsynaptic synaptogenic signals.

Transsynaptic Adhesion Complexes as Bidirectional Synapse Organizers

Adhesion molecules are central organizers of specialized cellular junctions in all tissues. Importantly, several proteins with adhesive properties have emerged as regulators with synaptogenic activity (Fig. 17.9). One class of these factors are the neuroligins, postsynaptic adhesion molecules that can bind to neurexins, a family of receptors present on axons (Sudhof, 2008). Neuroligin-neurexin interactions mediate heterophilic adhesion across the synaptic cleft, thereby directly connecting the pre- and postsynaptic compartments. Heterologous expression of neuroligin in nonneuronal cells induces focal accumulations of neurexins and synaptic vesicle proteins in contacting axons (Scheiffele, Fan, Choih, Fetter, & Serafini, 2000). The neuroligin-induced presynaptic structures are capable of vesicle exo- and endocytosis upon depolarization, indicating that not only synaptic vesicles but the entire machinery for regulated exocytosis is recruited to these nascent presynaptic terminals. Interestingly, neurexins also serve as a synaptic receptor for another postsynaptic adhesion molecule called LRRTM2 (leucine-rich repeat protein 2). LRRTM2 drives presynaptic differentiation through direct interaction with axonal neurexins, therefore, providing an alternate neurexin ligand to neuroligins (de Wit et al., 2009). The neuroligin-neurexin and LRRTM2-neurexin transsynaptic complexes are part of a growing list of proteins with synaptogenic functions. One additional notable example is the postsynaptic receptor TrkC (Takahashi et al., 2011). TrkC is a well-known receptor for neurotrophins that regulates neuronal survival (see Chapter 19). Surprisingly, at synapses TrkC engages in adhesive interactions with presynaptic receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases (RPTPs). These interactions promote recruitment of synaptic vesicles to presynaptic sites and the maturation of the postsynaptic structures. Notably, the synaptogenic function of TrkC does not require the presence of neurotrophins or the TrkC kinase activity. This suggests that in addition to its role in cell survival, TrkC has evolved functions that resemble an adhesion molecule.

How do transsynaptic adhesion complexes promote the assembly of synaptic junctions? The synaptogenic functions of multiple transsynaptic adhesion complexes appear to converge onto a common platform of presynaptic signal mediators. Neurexins couple via PDZ-domain interactions to a group of multidomain scaffolding molecules including Lin-2/CASK and Lin-10/Mint. RPTPs (the presynaptic receptors for TrkC) couple to liprins, which in turn interact with Lin-2/CASK. This presynaptic scaffolding complex might link synaptic adhesion molecules to voltage-gated calcium channels—the key calcium source for regulated secretion at the active zone (Missler et al., 2003). Currently, evidence for essential roles for any of these scaffolding molecules in presynaptic assembly in vertebrates is lacking. However, analysis of invertebrate model systems highlighted that these proteins are indeed key regulators of presynaptic assembly. C. elegans liprin has been recovered as a mutation called synapse-defective-2 in a genetic screen for mutant nematodes with altered presynaptic differentiation (Jin, 2002). In synapse-defective-2 mutant worms active zones are unusually lengthened and synaptic vesicles are diffusely localized along presynaptic sites. By analogy with the RPTP-liprin interactions observed in vertebrates, SYD-2 acts downstream of the receptor tyrosine phosphatase called PTP-3A. Exploring the function of liprins/Syd-2 in vertebrates is complicated by the fact that multiple independent genes encode liprin isoforms. However, expression, localization and biochemical interactions of liprins are consistent with a role in presynaptic assembly.

The concept of submembrane scaffolds organized by synaptic adhesion complexes not only applies to presynaptic organization but such scaffolds may also underlie the concentration of postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors. In analogy to AChR clustering at the neuromuscular synapse, transsynaptic signals recruit Rapsyn-like cytoplasmic proteins that provide a scaffold lining the postsynaptic membrane. Different forms of such scaffolds selectively retain postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors at the appropriate sites. Biochemical studies have identified a vast array of such scaffolding proteins. These proteins are characterized by combinations of protein–protein interaction domains, making them well suited to cross-link postsynaptic receptors into larger complexes (Kim & Sheng, 2004). Neuroligins bind, via PDZ-domain interactions, to SAP102 and PSD-95, major components of the glutamatergic postsynaptic scaffold. Aggregation of neuroligins results in the recruitment of the scaffolding proteins and NMDA-type glutamate receptors (Chih, Engleman, & Scheiffele 2005; Graf, Zhang, Jin, Linhoff, & Craig, 2004). Mice lacking neuroligin proteins show a subtle reduction in synapse density and a significant loss of postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors from synapses (Varoqueaux et al., 2006). These studies highlight the coupling of neurotransmitter receptors to adhesion molecules and a potential role for scaffolding molecules in this process. The importance of these interactions is further emphasized by the association of mutations in scaffolding and adhesion molecules with autism-spectrum disorders in human patients (Box 17.2).

Box 17.2 Synaptic Targets in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Human genetic studies have uncovered genetic risk factors for autism-spectrum disorders. Autism is characterized by impairments in social interactions and communication. Patients exhibit a spectrum of restricted interests, ritualized behaviors, and stereotyped, repetitive movements. Autism is considered neurodevelopmental in origin as the defects emerge in the first years of life during the developmental time period of synapse formation and remodeling. Multiple genetic alterations (mutations or copy number variations) identified in patients encode proteins with synaptic function. For example, genes encoding the neurexin-neuroligin adhesion complex have emerged as autism candidate genes, including Nrxn1, Nlgn1, Nlgn3, Nlgn4, and the associated scaffolding molecules Shank2 and Shank3. Mutant mice recapitulating these mutations exhibit behavioral alterations that mimic core defects of autism and serve as models for developing therapeutic strategies.

Steven J. Burden and Peter Scheiffele

The concept that scaffolding molecules contribute to the clustering of postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors applies to both excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Importantly, these synapses differ not only in their presynaptic neurotransmitters and postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors but also in their scaffolding proteins. In fact, scaffolding molecules may ensure that the appropriate neurotransmitter receptors are selectively recruited to excitatory and inhibitory synapses, respectively. The scaffolding protein gephyrin represents one of the best-understood examples for the scaffold-mediated postsynaptic receptor clustering at inhibitory synapses. Gephyrin is a cytoplasmic protein that associates with the glycine receptor and is essential for receptor clustering at synaptic sites (Kneussel & Betz, 2000). Gephyrin is well equipped to serve as a scaffolding protein that links receptors to the cytoskeleton; it binds with high affinity to polymerized tubulin, the actin-binding protein profilin, and the lipid-binding protein collybistin. Thereby, gephyrin may link membrane lipids, neurotransmitter receptors, and cytoskeletal elements to stabilize postsynaptic specializations. Moreover, the gephyrin-collybistin complex is well positioned to recruit GABA-A-receptors in response to transsynaptic adhesion through a mechanism analogous to the scaffolding protein interactions at glutamatergic synapses. Neuroligin-2, a member of the neuroligin protein family that is concentrated at GABAergic synapses, activates collybistin, which in turn tethers gephyrin at the postsynaptic membrane. These gephyrin clusters then retain glycine and GABA-A-receptors at postsynaptic sites (Poulopoulos et al., 2009). In the hippocampus of neuroligin-2 knockout mice, the perisomatic accumulation of gephyrin and GABA-A receptors is reduced, which highlights an essential role for neuroligin-2 in nucleating a cytoplasmic protein platform of GABAergic synapses. In summary, multiple transsynaptic adhesion systems provide bidirectional signals that cooperate in the organization of pre- and postsynaptic structures.

Postsynaptic Neurotransmitter Receptors as Effectors of Anterograde Signaling

While cytoplasmic scaffolding protein interactions provide one important pathway for the clustering of postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors, direct extracellular (scaffold-independent) interactions with neurotransmitter receptors themselves have emerged as a second mechanism (Fig. 17.9). Ionotropic glutamate receptors are tetramers, generally composed of two molecules each of two different subunits. In addition to ligand-binding and pore-forming domains, glutamate receptor subunits contain an extracellular amino-terminal domain (NTD). Proteins that directly bind to these NTDs serve as anterograde signals for the synaptic recruitment of glutamate receptors. The neuronal pentraxins were the first such anterograde signals to be identified. Pentraxins (NARP and NP1) are released from axons and interact directly with the NTD of AMPA-receptor (GluA) subunits. This interaction is sufficient to drive the synaptic aggregation of receptors at glutamatergic postsynaptic sites (O’Brien et al., 1999). Importantly, NTD-mediated interactions for postsynaptic differentiation are not unique to AMPA-type glutamate receptors but are emerging as a general principle. The NTD of the NMDA-receptor subunit GluN1 mediates direct interactions with EphB2, a member of the Eph-receptor family of receptor tyrosine kinases (Dalva et al., 2000). EphB-receptors form transsynaptic complexes with their ligands, called ephrinBs. These interactions nucleate a tripartite complex consisting of ephrinB, EphB-receptor, and NMDA-receptors, providing an anterograde signal for NMDA-receptor recruitment to synapses. Notably, EphB-receptors had been initially recognized for their critical roles in axon guidance and topographic mapping. The function of the EphrinB-EphB-receptor system at synapses highlights additional functions. In fact, other axon guidance molecules were recently identified as regulators of synapse formation. In many cases the signaling read-out downstream of these receptors varies between the different steps of neural development: some receptors that mediate repulsive signaling during axon guidance (such as EphB) have adhesive and stabilizing functions at synapses. How this functional switch is achieved is currently unknown.

Arguably, the most remarkable example for direct neurotransmitter receptor interactions in synaptic differentiation is provided by the GluD2 protein. GluD2 forms homo-tetramers and shares the same domain organization with AMPA- and NMDA-type receptors. However, owing to amino acid alterations in the receptor pore, GluD2 does not appear to mediate any currents. GluD2 is selectively expressed in cerebellar Purkinje cells where it is critical for synaptic connectivity and function. Mice lacking GluD2 suffer from cerebellar ataxia—that is, defects in motor coordination and balance. Parallel fiber synapses that form between cerebellar granule cells and Purkinje cells detach, indicating a severe weakening of transsynaptic adhesion. The GluD2 NTD stabilizes synapses through the presynaptic ligand cerebellin-1 (Cbln1), a small, secreted protein (Uemura et al., 2010). Whereas the GluD2 receptor is accumulated in Purkinje cell dendritic spines, Cbln1 is secreted from cerebellar granule cells and concentrates at parallel fiber synapses with Purkinje cells. Interestingly, Cbln1 binds to presynaptic neurexins (Fig. 17.9)—that is, the same presynaptic receptor that also transduces synaptogenic activities of postsynaptic neuroligins and LRRTM proteins (see above). In summary, Neurexin, Cbln1, and GluD2 form a tripartite complex that promotes synapse formation via the amino-terminal domain of GluD2. GluD2 is expressed exclusively in cerebellar Purkinje cells but neurexins and Cbln molecules are found more broadly in the nervous system and are likely to contribute to differentiation of other synapses as well. In fact, the cell type–specific function of the three anterograde synapse-organizing systems described in this paragraph highlight an important principle for CNS synapse formation: synapses formed between different neuronal partners have evolved a diverse range of signaling modules that control their assembly. The Agrin-Lrp4/MuSK complex is a universal signal for stabilization of all neuromuscular synapses. By contrast, signaling systems in the CNS are much more diverse and different synapses assemble by different mechanistic rules.

Glial-Derived Signals for Synapse Development

All transsynaptic signals we have discussed so far are exchanged directly between the pre- and postsynaptic partners. However, synapses are tripartite structures in which glial cells assume highly specialized morphologies and functions (Fig. 17.7). Importantly, some synaptic differentiation factors are derived from glial cells and coordinate the assembly of pre- and postsynaptic structures. Cultured astrocytes greatly enhance the number of synapses formed by cultured purified retinal ganglion cells (Eroglu & Barres, 2010). Astrocytes secrete multiple factors to control various aspects of synapse formation. One of these factors is thrombospondin (TSP), a large secreted proteoglycan molecule (Fig. 17.9). TSP induces morphologically defined synapses in cultured neurons, and mutant mice with perturbed TSP expression have fewer synapses. This suggests that this astrocyte-derived protein is required for synapse formation in the intact nervous system. The activity of TSP is mediated by interactions with both pre- as well as postsynaptic receptors. A presynaptic TSP receptor is the protein alpha-2-delta, a transmembrane protein associated with voltage-dependent calcium channels. On the postsynaptic side, TSP interacts with neuroligin-1, which in turn couples to NMDA-type glutamate receptors. This example highlights that glial cells play important roles in determining the formation and function of synapses during development. Additional glial-derived signals for synapse formation are likely to exist and remain to be discovered.

Surface Recognition Molecules in Synaptic Specificity

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of synaptic specificity is arguably the most exciting unresolved question in the field of CNS synaptogenesis. A leading model is that selective transsynaptic interactions are achieved by an adhesive code. Such a code could be generated by corresponding attractive cues in pre- and postsynaptic cells, matching appropriate partners through adhesive interactions. Such attractive cues for selective wiring are complemented by repulsive signals that limit the interaction between inappropriate partners. In the following, we will discuss examples for both mechanisms.

Cadherins are the first proteins proposed to function as adhesive synaptic specificity factors. Cadherins are a family of homophilic adhesion molecules that are major regulators of cell morphology and function in all tissues. In the CNS, cadherins are concentrated at synapses. Since there are about 20 different subtypes of classical cadherins these proteins could encode selective interactions between synaptic partners. In many brain areas specific cadherin isoforms are selectively expressed in corresponding pre- and postsynaptic partners, making them excellent candidates to impose specificity on the synapse formation process. This hypothesis has been tested in the hippocampal mossy fiber projection in mice (Fig. 17.10). In the hippocampal circuit, mossy fiber axons derived from the dentate granule cells (DG) form large glomerular synapses selectively on CA3 pyramidal cells. Interestingly, preferential synapse formation between DG and CA3 cells is maintained, even in dissociated cultures of hippocampal neurons where spatial constraints imposed by the hippocampal architecture are absent. Therefore, it is indeed cellular properties and not cell location in the neuropil that are important for selective synaptic interactions. DG and CA3 cells both express the same cadherin isoform (cadherin-9). In the absence of cadherin-9, DG-CA3 synapses are under-developed and form in lower numbers (Williams, et al., 2011). These experiments provide a first glimpse of critical roles for cadherin-mediated adhesion in selective synapse formation. Given that multiple different cadherin isoforms are found throughout different brain regions and neuronal circuits, analogous cadherin-mediated interactions may contribute to further cases of synaptic specificity.

Figure 17.10 Model mechanisms for synaptic specificity. (A) In the hippocampus, dentate granule cells (DG) form synapses selectively on pyramidal cells in the CA3 region. Pre- and postsynaptic partners express the same homophilic adhesion molecule (cadherin-9) and thereby preferentially form synapses with each other. (B) In the vertebrate retina, the analysis of laminar specificity of neurite elaboration is facilitated by stereotyped layered organization of the inner plexiform layer (sub-laminae S1-S5). In this system, attractive and repulsive signals have been identified which guide synaptic specificity. Subsets of amacrine and bipolar cells in the inner nuclear layer contain different isoforms of the protein Sidekick (Sdk1 or Sdk2). Through homophilic adhesion, these cells form lamina-specific synaptic connections on the dendrites of Sdk1 or Sdk2-positive ganglion cells, respectively. In the same system, local repulsion is used as an additional specificity mechanism. The neurites elaborated by PlexinA4-positive amacrine cell (PlxA4+) are repelled by semaphorin6A (Sema6A) expressed in sub-laminae S3-S5. Thereby, PlxA4+ neurites are restricted to sub-laminae S1 and S2.

Figures adapted from Williams, de Wit, and Ghosh (2010) and Yamagata and Sanes (2008).

Beside cadherins, additional homophilic adhesion molecules have been implicated in synaptic specificity. The vertebrate retina is a particularly useful system for the analysis of selective wiring due to its stereotyped organization (Fig. 17.10). Amacrine and bipolar cells elaborate neurite arborizations in the inner plexiform layer, a laminar region where synapses on retinal ganglion cell dendrites are established. The inner plexiform layer is divided into so-called sublaminae defined by the restriction of neurites from distinct amacrine and bipolar cells and their retinal ganglion cell targets. Cells elaborating neurites and synapses in specific sublaminae differ in their activation upon visual stimuli (ON and OFF cells; see Chapter 9 for details). A family of immunoglobulin domain proteins, called Sidekicks and the closely related DSCAMs, are expressed in synaptic partners (Yamagata & Sanes, 2008). Sidekicks and DSCAMs mediate homophilic adhesion and direct axo-dendritic interactions of specific pairs of amacrine and retinal ganglion cells to specific sublaminae (Fig. 17.10). Therefore, similar to the hippocampus, a substantial degree of laminar specificity can be achieved through adhesive interactions between pre- and postsynaptic partners. However, not all aspects of laminar specificity rely on attractive interactions. Repulsion from inappropriate targets has emerged as a second fundamental mechanism for achieving synaptic specificity. A compelling example for this mechanism is observed for the laminar stratification of amacrine cell neurites (Matsuoka et al., 2011). A subclass of amacrine cells (containing the neuromodulator dopamine or calbindin) elaborates neurites and synapses predominantly in the S1 and S2 sublaminae of the IPL. This restriction is achieved by repulsive signals transduced through the Plexin-Semaphorin receptor-ligand pair of guidance molecules. The PlexinA4 receptor is expressed in the amacrine cells, whereas the transmembrane Semaphorin 6A ligand is concentrated in sublaminae S3-S5, thereby forming a repulsive barrier for PlexinA4-positive neurites (Fig. 17.10). Removal of either molecule results in neurite mistargeting.

These two examples of attractive and repulsive mechanisms for the laminar restriction of neurites and synapses explain a small number of the many selective interactions observed in the neuronal circuits of the retina. The intricate pattern of laminar restriction of the multitude of additional cellular interactions is likely achieved by a combination of cues that target neurites to or exclude them from specific domains. It is an open question whether synaptic specificity in neuronal networks, which are not organized in anatomical laminar structures, follows similar principles or whether new, yet unanticipated mechanisms are at work.

Summary

The diversity of synapses found in the nervous system is likely to be matched by an equally diverse array of mechanisms producing the synapses. These mechanisms are only now beginning to be elucidated. Prime candidates at present for synaptogenic roles include transmembrane proteins interacting with cognate receptors on the apposing cell surface (e.g., neuroligin/neurexin; RPTPs/TrkC receptors), diffusible molecules that instruct synaptic development in target cells (e.g., FGF22) or that interact directly with synaptic components (e.g., NARP, Cbln1), and intracellular components that act locally to organize synaptic constituents (e.g., gephyrin). Advances in visualizing neuronal connectivity in the intact brain have paved the way to the identification of signals that inhibit (Plexin-Semaphorin) or promote (cadherin-9) interactions between specific synaptic partners providing the first insights into synaptic specificity.

References

1. Aberle H, Haghighi AP, Fetter RD, McCabe BD, Magalhaes TR, Goodman CS. Wishful thinking encodes a BMP type II receptor that regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron. 2002;33:545–558.

2. Arber S, Burden SJ, Harris AJ. Patterning of skeletal muscle. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2002;12:100–103.

3. Beeson D, Higuchi O, Palace J, et al. Dok-7 mutations underlie a neuromuscular junction synaptopathy. Science. 2006;313:1975–1978.

4. Bergamin E, Hallock PT, Burden SJ, Hubbard SR. The cytoplasmic adaptor protein Dok7 activates the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK via dimerization. Molecular Cell. 2010;39:100–109.

5. Burden SJ, Sargent PB, McMahan UJ. Acetylcholine receptors in regenerating muscle accumulate at original synaptic sites in the absence of the nerve. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1979;82:412–425.

6. Burgess RW, Skarnes WC, Sanes JR. Agrin isoforms with distinct amino termini: differential expression, localization, and function. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;151:41–52.

7. Chih B, Engelman H, Scheiffele P. Control of excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation by neuroligins. Science. 2005;307:1324–1328.

8. Dalva MB, Takasu MA, Lin MZ, et al. EphB receptors interact with NMDA receptors and regulate excitatory synapse formation. Cell. 2000;103:945–956.

9. DeChiara TM, Bowen DC, Valenzuela DM, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK is required for neuromuscular junction formation in vivo. Cell. 1996;85:501–512.

10. de Wit J, Sylwestrak E, O’Sullivan ML, et al. LRRTM2 interacts with Neurexin1 and regulates excitatory synapse formation. Neuron. 2009;64:799–806.

11. Engel AG, Ohno K, Sine SM. Sleuthing molecular targets for neurological diseases at the neuromuscular junction. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:339–352.

12. Eroglu C, Barres BA. Regulation of synaptic connectivity by glia. Nature. 2010;468:223–231.

13. Escher P, Lacazette E, Courtet M, et al. Synapses form in skeletal muscles lacking neuregulin receptors. Science. 2005;308:1920–1923.

14. Flanagan-Steet H, Fox MA, Meyer D, Sanes JR. Neuromuscular synapses can form in vivo by incorporation of initially aneural postsynaptic specializations. Development. 2005;132:4471–4481.

15. Fox MA, Sanes JR, Borza DB, et al. Distinct target-derived signals organize formation, maturation, and maintenance of motor nerve terminals. Cell. 2007;129:179–193.

16. Francis MM, Evans SP, Jensen M, et al. The Ror receptor tyrosine kinase CAM-1 is required for ACR-16-mediated synaptic transmission at the C elegans neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 2005;46:581–594.

17. Gally C, Eimer S, Richmond JE, Bessereau JL. A transmembrane protein required for acetylcholine receptor clustering in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2004;431:578–582.

18. Garner CC, Zhai RG, Gundelfinger ED, Ziv NE. Molecular mechanisms of CNS synaptogenesis. Trends in Neurosciences. 2002;25:243–251.

19. Gautam M, Noakes PG, Mudd J, et al. Failure of postsynaptic specialization to develop at neuromuscular junctions of rapsyn-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;377:232–236.

20. Glass DJ, Bowen DC, Stitt TN, et al. Agrin acts via a MuSK receptor complex. Cell. 1996;85:513–523.

21. Grady RM, Zhou H, Cunningham JM, Henry MD, Campbell KP, Sanes JR. Maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular synapse: genetic evidence for roles of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Neuron. 2000;25:279–293.

22. Graf ER, Zhang X, Jin SX, Linhoff MW, Craig AM. Neurexins induce differentiation of GABA and glutamate postsynaptic specializations via neuroligins. Cell. 2004;119:1013–1026.

23. Hall AC, Lucas FR, Salinas PC. Axonal remodeling and synaptic differentiation in the cerebellum is regulated by WNT-7a signaling. Cell. 2000;100:525–535.