CHAPTER 8

Investment Decisions (Marriott Corporation and Gary Wilson)

In Chapter 7, we outlined five policy guidelines that Marriott's Board of Directors had set. To review, the guidelines were:

- Debt should be maintained between 40% and 45% (or debt + leases at 50–55%) of financing.

- The Moody's commercial paper rating should be at P-1 or better (this is roughly equivalent to a bond rating of A or above).

- The principal source of financing should be domestic, unsecured, long-term, fixed-rate bonds.

- No convertible debt or straight preferred stock should be issued.

- The dividend payout should not be increased substantially.

The reasons for setting these guidelines are described in Chapter 7.

Two years later, Marriott is generating excess cash, and without a change in its policies its debt/equity ratio will fall below the level Marriott considered optimal. As discussed, from a corporate finance point of view, excess cash is equivalent to negative debt. That is, a firm with $0 cash and $500 million in debt is much more leveraged than a firm with $500 million in cash and $600 million in debt. When we calculate actual debt/equity ratios, we must net out excess cash against debt (we also net out excess cash and debt when we lever and unlever betas).

Given excess cash, as we noted in Chapter 7, Marriott had five choices. It could:

- Grow its existing businesses faster

- Acquire new businesses

- Pay down its debt

- Pay higher dividends

- Buy back stock

The first two solutions are product market solutions. The last three are financial solutions.

We ended the last chapter by noting that Marriott had decided that repurchasing shares was a good financing decision. The question now is: At what price (i.e., should they repurchase 10 million shares at $23.50)?

As previously noted, for any project there is always a price high enough to make the NPV negative. In addition, but not always, there is usually a price low enough to make the NPV positive. Now as simple as that sounds, this is really a very important point in finance. A project can switch from negative NPVs to positive NPVs, or vice versa, depending on the price bid. This sounds simple, but it is very important for valuation, and we will discuss it more fully later in the book.

Marriott is making both a financing as well as an investing decision. Making a correct financing decision does not guarantee the firm will also make a correct investment decision—and vice versa. One decision can be correct while the other can be incorrect, or both correct, or both incorrect. That is, repurchasing stock could move Marriott to the correct capital structure, but the firm could pay too high a price for the shares. On the other hand, Marriott could have an incorrect capital structure decision, yet a low price for the repurchase decision (e.g., at a price per share at which Marriott would want to buy). Thus, these decisions, while linked, don't have to both be correct. In the last chapter, we discussed the financing decision. In this chapter, we introduce and discuss the investment decision. We are not going to do a complete valuation. We will deal with valuations later in the book.

WHAT IS THE CORRECT PRICE?

So, is Marriott's offer price of $23.50 for its own stock too much? The stock price at the time is $19 5/8 (stocks on the NYSE used to be quoted in eighths before 2001, when they became decimalized). Marriott's EPS is $1.96, giving it a P/E of 10. Its book value is $12.90. So here's an important question: The market says the stock is worth $19.63. Why would anyone pay more than the market? Why would Marriott pay $23.50 rather than $19.63?

How much of a premium is Marriott offering over the market? $3.87, or 20%. A $39 million premium on the 10 million shares. If Marriott truly has excess cash, it can afford to pay the premium, but should it? Why are the shares worth $39 million more than the market value? Is the market wrong and Marriott right, or is the market right and Marriott wrong?

Sometimes a premium is paid in order to gain control of a firm.1 This is not the case with Marriott, since the Marriott family already controls the firm—they own 20% of the stock and constitute half the Board of Directors. Thus, control is clearly not an issue for Marriott, although it may be an issue in other cases.

HOW SHOULD MARRIOTT BUY ITS SHARES?

Let's take a detour and ask a slightly different question. If the stock is selling for $19.63 in the market, why doesn't Marriott go into the market and buy it there? Why pay $23.50 in a tender offer, if the firm can buy it in the market for $19.63? One reason Marriott is offering more than the market price is because it doesn't think it can get 10 million shares for $19.63. As it buys shares, the price will go up. However, suppose Marriott can buy 1 million shares for $20, then another million for $20.50, then the next million for $21.00, and so on. This means on the first million shares it saves $3.5 million. On the second million shares it saves $3 million, and so on. Actually, there's an important reason Marriott does not buy shares this way. It's illegal to repurchase shares that way if Marriott does not first inform the market. If Marriott tries to buy the stock quietly (without informing the market), regulations restrict its repurchases to 25% of the four-week float (i.e., volume).

Let's look at what this means. Marriott's volume in October 1980 was 17,825,000 shares traded. This means the most Marriott can buy privately over that four-week period is 4,456,250 shares. The trading volume for November was 5,844,000, so the most Marriott can buy privately in November is 1,461,000. In December, the volume was 7,014,000, so the most Marriott can buy privately is 1,753,500. So if Marriott wants to buy 10 million shares quietly without announcing it first to the market, it has to buy the shares very slowly over time.

There is another alternative, however: Marriott can publicly announce its intent, and then buy the shares as an “open-market” repurchase. That is, if Marriott publicly announces its repurchase plans, it is not restricted by the 25% rule. The 25% rule is in place to prevent firms from manipulating the stock price.2 If a firm announces it will purchase up to 10 million shares on the market, it can purchase as many shares as it wants at whatever price it wants. So why not do it that way? The problem with announcing the intended purchase is that the share price usually rises on the announcement. But will it rise above $23.50? The question is, if 10 million shares will be tendered at $23.50, wouldn't some of those shares be sold at a price less than $23.50? Couldn't Marriott first buy a million shares at $21 in the market, and then another million at $21.50 and so on? In other words, can a firm walk up the supply curve, or does the whole supply curve shift?

Tender offers are an alternative to a firm repurchasing its shares over time, either privately or through a public open-market repurchase program. In a tender offer, a firm buys back a number of shares at a point in time. A tender offer must announce the quantity of shares to be repurchased and a range of prices the firm is willing to pay, or it must announce a set price the firm will pay and a range of the quantity of shares to be repurchased. This is because tender offers are regulated to have either a range of prices or a range in the quantity of shares to be repurchased but not both. This regulation is meant to protect shareholders. In addition, tender offers are open for a fixed amount of time, although they must be open a minimum of 20 trading days.

An important feature of tender offers versus open-market repurchases is that the open-market repurchases are typically a less expensive way to repurchase shares, but one that takes longer. By contrast, tender offers are more expensive but quicker. Tender offers and their variants are discussed later in the context of hostile takeovers.

Since open-market purchases are cheaper but slower than tender offers, a firm must ask itself: Where does it think the stock price is going and how quickly will it get there? If the firm believes the stock price will remain low, it is cheaper to do an open market purchase. If the firm believes the stock price will double within six months, it may be cheaper to do a tender offer.

Back to the Share Price

Let's return to the valuation. To review, Marriott is considering a tender offer of $23.50. Is extra value coming from higher EPS or a tax shield? We know Marriott's EPS should rise if it issues debt to do a stock buyback. Table 8.1 shows us that the pro forma change in EPS is from $1.96 to $2.19 after the proposed share repurchase. At a P/E of 10, this makes the stock price $21.90. However, we know that the P/E of 10 is a maximum. From the last chapter, we know that if we increase the debt ratio, we may increase EPS, but we also decrease the P/E. Thus, the EPS may go to $2.19, but the P/E will fall below 10. As such, we can't get to a stock price of $23.50 using the P/E effect.

TABLE 8.1 Marriott Corporation Current and Pro Forma Earnings per Share (EPS)

| Net income as stated | $71,000,000 | |

| Outstanding shares | 36,225,000 | |

| Current EPS | $1.96 | |

| Net income as stated | $71,000,000 | |

| New debt (10 million shares * $23.50/share) | $235,000,000 | |

| After-tax cost of interest * = 10.6% * (1 – 0.46) = | 5.724% | |

| After-tax cost of debt on repurchased shares | ($13,451,400) | |

| Pro forma adjusted net income | $57,548,600 | |

| Pro forma adjusted outstanding shares** (36.225 million − 10 million) | 26,225,000 | |

| Pro forma EPS | $2.19 | |

* Assumes a 0.5% premium to the 30-year U.S. Treasury bond rate, which was 10.1% at the end of 1979, and a corporate tax rate of 46%.

** Marriott had 36.225 million shares outstanding at the end of 1979.

What is the tax shield worth to Marriott? The tax shield3 for Marriott on $235 million in debt is approximately $47 million if we assume a 20% tax shield.4 With a premium of $3.90/share over the current market price, the stockholders whose stock is repurchased are given a total premium of $39 million. There are currently 36.2 million shares outstanding. If Marriott repurchases 10 million shares, this will leave 26.2 million shares outstanding. Thus, with a tax shield of $47 million, $39 million of which is given to the selling shareholders, the price for the remaining 26.2 million shares is never going to reach $23.50.

Could the higher stock price be justified because of future inflation? Is the market missing the fact that the stock price will rise in the future due to inflation? Since the market price of the stock is $19.60 but the book value is $12.90, it is clear that investors do understand the firm is worth more than book value. Thus, future inflation is at least partially accounted for and probably cannot explain the premium of $3.90 per share Marriott is willing to pay.

So, we again return to the question: What is the real reason that Marriott (and Gary Wilson) is willing to pay more than the market for Marriott's stock? The answer appears to be because Marriott currently has a very different outlook about its future prospects than does the market. In 1980, the average EPS forecast for Marriott from all analysts was $2.08, with a high-end estimate of $2.20.5 The average ROE forecast was 14.8%, with the highest estimate of 16%. The forecast for 1983 was an average EPS of $3.38 (highest estimate of $3.80) with an average ROE of 15.4% (highest estimate of 17%). This is what the analysts (and presumably the market) expected. What did Marriott expect? Wilson, in 1980, stated that he expected Marriott's ROE to be at least 20% by 1983—well above the high-end analyst estimate. Furthermore, he expected the return on assets to go from 6.6% to 8.7% between 1979 and 1981. This is a 32% increase in Marriott's return on assets.

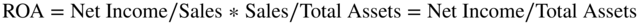

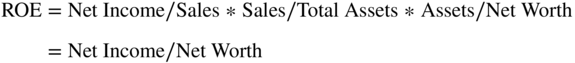

Let's discuss the relationship between ROE and ROA. Return on equity equals profits over assets, which can be written as profits over sales (profit margin) times sales over assets (capital intensity).

If you multiply this equation by leverage, measured as assets to net worth (assets/equity), you get ROE (return on equity or profits to net worth).

This formula is an important one in finance and, as noted before, is called the DuPont formula.6 It says that return on assets equals profit on sales times sales on assets times assets to net worth. It also says that you can increase ROE by increasing profitability (making more profit per dollar of sales), increasing asset turns (generating more sales with the same assets), or increasing leverage (borrowing a greater percentage of your assets).

Thus, if a firm keeps assets to net worth the same, that is, keeps leverage the same and return on assets goes up 32%, then ROE will also go up by 32%. So the analysts (i.e., the market) are saying they expect ROEs of 16% and 17% in 1980 and 1983 (and they expect EPSs of between $2 and $4). Meanwhile, Marriott is saying it expects ROE to be at least 20%, and, if you work it out through the DuPont formula, it could even be higher. So clearly, Wilson and Marriott are more optimistic than the market about the firm's future.

So the situation is as follows: the market says Marriott's stock is worth $19.60. Wilson and Marriott clearly believe it is worth more. This is not due to the tax shields. It also has nothing to do with inflation. It is simply a different view of the future. Furthermore, Wilson doesn't think the market's right about the market's forecasted inflation. Thus, tax shields and inflation may help influence Wilson's and Marriott's view but are not the principal determinants. Wilson's different view of the future combined with his view that the debt level will go down as Marriott gets more profitable leads him to recommend that Marriott buy back its shares.

The Marriott Family's Decision

So if Marriott is tendering for 10 million shares, how is the Marriott family betting? That is, what are they going to do with their shares? At this time the Marriott family intends to hold their shares and not tender. So here's the next question: Who do you believe? Do you believe Wilson and the Marriott family, or do you believe the analysts?

Suppose Gary Wilson is wrong. What are the consequences for Marriott? First, Marriott will have paid a premium of $39 million above market value. In addition, Marriott's debt levels will go up significantly. While the debt levels will not put Marriott into financial distress, it does mean Marriott may lose financial flexibility and have to forego future opportunities. Is Wilson/Marriott betting the company on this? No, they are not. There is no real worry about losing the company to bankruptcy or a takeover. Nobody's going to take Marriott over because the Marriott family owns 20% of the stock, and if the tender offer goes through, they will own 29%.

Marriott will add a lot of debt but not enough to risk the firm's viability. Even so, Marriott is going to bet a lot on this. So here's a new question. Suppose you bought the stock last week for $19.60 a share. Marriott offers $23.50 in a tender offer. Should you tender your shares? That question really asks whether you believe Wilson and Marriott or whether you believe the market.

Let's discuss what the Marriott family is doing with their shares. If Marriott tenders for 10 million shares total and the Marriott family says, “We're all in, we are tendering all of the 6.5 million shares we own.” Does this influence your decision? By contrast, since we know the Marriotts decided not to tender any of their shares, how does this influence your decision? Examining what the firm's insiders do with their own shares or the firm's shares is called signaling.

Let's summarize for a moment. Marriott can do this share repurchase as an open-market purchase. Marriott can do this as a tender offer. Marriott can't, however, buy the shares secretly on the market because it is illegal, as stated above, under SEC rules to purchase more than 25% of the average traded volume over any four-week period.

THE LOAN COVENANTS

Switching gears, let's talk a little bit about the loan covenants. Loan covenants are restrictions placed in a debt contract by lenders to monitor and control the borrowing firm's actions. If a covenant is violated, even if the interest is paid on time, the borrower is technically in default and can be forced to pay back the debt immediately.7 Covenants are usually stated as ratios that include the amount and percentage of debt.

If Marriott issues debt to repurchase 10 million shares of equity, what happens to its loan covenants? Although not listed here, a huge increase in debt will cause Marriott to be in violation of some of its covenants. In fact, even before the buyback, Marriott is already violating one of the covenants, which prohibits negative working capital.

However, despite this technical violation, Marriott's creditors did not demand repayment. Gary Wilson/Marriott did not correct the violation and lenders waived the covenant. In fact, on page 18 of its 1979 Annual Report, Marriott states: “Marriott has no requirement for positive working capital, since it principally sells services rather than goods for cash. Therefore, the company maintains low receivables and cash balances. . . monetary assets that depreciate in value due to inflation.” It goes on to say, “Negative working capital is a source of interest-free financing.” What Marriott and Wilson are essentially saying is that Marriott has negative working capital, and it's great to have negative working capital because it's free financing. We try to get negative working capital. We have very low receivables, and if we can stretch out our payables, then our suppliers finance us at no cost.

Do Marriott's banks care if the firm has negative working capital? Apparently not. The banks could force repayment since Marriott is in violation of one of their covenants. This is true despite the fact that Marriott is paying the interest and principal. So why have none of Marriott's bankers called in any of Marriott's loans? The simple answer is that Marriott would go to another bank and borrow there instead. Marriott's banks have implicitly waived the covenant violations. In practice, loan contracts have covenants to protect lenders, but if the bank feels that the covenant being violated is not putting the loan at risk, the bank will waive it.

To summarize, Marriott has 40–45% debt, has lots of assets backing its leverage, is making its payments on time, and has a positive cash flow that is getting better. While Marriott is in violation of one of its covenants, if the banks want to force repayment, Marriott will simply switch its banks with another syndicate. The banks won't play hardball since Marriott is a good client, doing good business.

Also, Marriott has a very different view than the analysts of where the firm is going and where the market interest rates are going. Gary Wilson comes to the Marriott family and says, “We should borrow $235 million and use it to tender for 10 million shares at $23.50.” As a result, the family decides to authorize the repurchase of shares but not tender any of their shares.

THE IMPACT OF THE PRODUCT MARKET ON FINANCIAL POLICIES

As noted above, Marriott is making two simultaneous corporate finance decisions. Are they good or bad? The first is a capital structure decision. By borrowing $235 million, Marriott will increase the debt in its capital structure above 40–45%, but possibly only temporarily. If Gary Wilson is right and Marriott does not issue more debt, then the firm will fall below the target debt ratio. This debt issue initially overshoots, but it will dynamically come back down. The second decision is an investment decision. If the market is right, then $23.50 is way too much to pay for Marriott's stock. If Gary Wilson is right, however, $23.50 is a reasonable price, and Marriott might be buying the shares cheaply compared to what they will be worth in the future.

What is driving these decisions is Marriott's major policy change in its product market operations. As noted in the prior chapter, Marriott went from owning its hotel properties to managing them. That is, Marriott now builds hotels and then sells them to investors while maintaining a contract to operate the facility as a Marriott hotel. Thus, Marriott used to have a lot of assets in place and, as a consequence, Marriott absolutely had to have access to the capital markets to fund for expansion. The firm has now changed. It went from owning to managing, and now the need for financing to grow assets is not as great.

What does this mean for our target debt rating? Does Marriott still have to maintain an A rating? It could, but it's nowhere near as important. Also, Marriott does not have to be able to obtain financing at all times. It can be more aggressive with its debt ratio; that is, it can increase its debt ratios, particularly in the short term. Add to this the fact that Marriott thinks its stock price is low, and we understand its willingness to pay a $39 million premium to the current market. If Marriott is not right, it is going to be saddled with a lot of debt over a long period of time. More importantly, if it is not right, it will forego a lot of investment opportunities.

Marriott's Repurchase Decision

So what happened? On January 24, 1980, Marriott announces it will buy 5 million shares at $22 a share for a total of $110 million. Marriott's tender specifies that it will buy any and all shares up to 5 million, but that it may buy up to 11 million, but not over. This means that Marriott is guaranteeing that if stockholders tender any amount up to 5 million shares, the firm will buy them all at $22. If stockholders tender over 5 million shares, Marriott has the option to buy them or not. Marriott also says it will not purchase more than 11 million shares.

Let us briefly discuss tender offers. When a firm makes a tender offer, the firm can guarantee a fixed price and a fixed number of shares. For example, a firm can tender for 5 million shares at $22 a share. However, it is rare to have a tender offer of this form anymore with a fixed price and a fixed number of shares. Generally, a firm will vary one of the two dimensions. It will fix the price, say $22, and offer to buy a range of shares, say between 5 and 11 million, as Marriott did. Alternatively, it will fix the number of shares, 10 million, and provide a range for the price, say $18 to $25. These are called Dutch auction tenders.8 So why doesn't a firm vary both the price and the number of shares, for example, offer to buy between 5 and 10 million shares at $18 to $22 per share? It is illegal not to fix one of the two parameters. The SEC has ruled that tender offers that vary both price and quantity put the stockholders at a disadvantage. Some tender offers were done this way in the past, but it is no longer allowed under SEC regulations. A firm can either set the price and vary the quantity or can set the quantity and vary the price.

So Marriott's initial tender offer on January 24, 1980, was 5 to 11 million shares at $22 per share. A week later, on January 31, Marriott sold six hotels to Equitable Life for $159 million, which Marriott then leased back. As a consequence, Marriott changed the tender offer to $23.50 a share for up to 10.6 million shares. A month later, on February 28, 1980, the tender offer expired, and 7.5 million shares had been tendered.

Was this a successful tender offer or not? If a firm makes a tender offer at $23.50 a share for 10 million shares, what's the worst thing that can happen to the firm? It could get all 36.2 million shares tendered. Why is this bad? First of all, it means the firm offered too high a price. The firm clearly didn't have to go that high. It also means, in some cases, the firm just put a price on itself. If a firm makes a tender offer for its shares at $23.50 and all the shares are tendered, a potential raider now knows the price at which they can take over the firm. If a firm does a tender offer for 10 million shares, it doesn't really want more than 10 million shares. If you see a tender offer for 10 million shares and 15 million come in, the firm priced it incorrectly. The firm wants to price the tender offer so that around 10 million shares come in.

Suppose a firm tenders for 10 million shares at $23.50 and zero come in or 1 million come in. This is also not a good thing. In this case, the firm has not changed its capital structure, as it has not repurchased the desired number of shares. Why? Because the price was too low. So one of the ways we can tell if a firm has priced a tender offer correctly is by how many shares come in. Thus, we can infer that Marriott's original offer of $22 a share for the 5 million shares was not getting enough stockholders to tender. As a consequence, Marriott upped the price to $23.50, and then 7.5 million shares were tendered. This is not a bad outcome. It is enough shares to change the capital structure, and the tender offer was not oversubscribed.9

How does a firm decide on the price and number of shares for a tender offer? In a tender offer, a firm is trying to determine the supply curve of its shares and then choose where on the supply curve it is going to price the tender. It's not a perfect process, and the firm depends heavily on the advice from investment banks regarding the supply curve.

THE CAPITAL MARKET IMPACT AND THE FUTURE

Ten days after the tender offer expired on March 10 1980, Moody's, because of the increase in Marriott's debt ratio, dropped Marriott's commercial paper rating from a P-1 to a P-2. Did Marriott care? It mattered some, but it did not matter that much, because Marriott was not as dependent on the market as it was before. In addition, the maximum amount Marriott's bond ratings were expected to drop was just one level, from a single-A to a triple-B. Marriott was willing to live with this.

Let's review what happened. In 1979, Marriott's EPS was $1.96, ROE was 17.2%, and its net income was $71 million. Long-term debt and leases were 49.6% of capital structure. The total amount of debt was $407 million. Marriott's working capital was $3.8 million. Its year-end stock price was $19.63. Then Marriott bought 7.5 million shares at a tender price of $23.50.

Was this a good deal for the shareholders who tendered, and therefore a bad deal for the Marriott family? It is important to note that only 7.5 million shares were tendered. This means that many more shareholders decided not to tender than those who tendered—many people believed the Marriott family and not the analysts.

In general, the market views a company's willingness to buy back shares at a premium where the management is not tendering its own shares as a positive signal. In addition, as we will discuss in a later chapter, if a firm issues shares, the stock price generally falls. That is, if a firm announces it is issuing equity, the stock price generally declines. The market interprets the share price of a firm that is willing to sell shares at the current price as meaning that the current price is probably too high.10

Table 8.2 documents Marriott's financial performance from 1979 to 1983.11 Sales grew at an average compound rate of 18.2% (from $1.51 billion in 1979 to $2.95 billion in 1983), net income grew at an average compound rate of 12.9% (from $71.0 million in 1979 to $115.2 million in 1983), while earnings per share increased from $1.95 in 1979 to $4.15 in 1983. At the same time Marriott's ROA and ROE both rose and then fell. Interestingly, while EPS grew a total of 113% (($4.15 – $1.95)/$1.95), net income only grew 62.3% (($115.2 – $71.0)/$71.0). Why did EPS rise so much more than net income? Because Marriott's debt level increased from 49.6% to 63.9%. As we now know, if a firm increases its leverage and net income remains constant, then both ROE and EPS will increase. In Marriott's case, it is simply issuing debt to replace equity. It is still the same firm with the same assets and the same operations. Marriott was not expanding or changing the management. Marriott was simply changing the way it financed the firm.

TABLE 8.2 Marriott Corporation Summary Financial Information from 1979 to 1983

| ($000s) | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 |

| Sales | 1,509,957 | 1,718,725 | 2,000,314 | 2,458,900 | 2,950,527 |

| Operating expenses | 1,358,972 | 1,551,817 | 1,809,261 | 2,218,569 | 2,710,196 |

| Operating profit | 150,985 | 166,908 | 191,053 | 240,331 | 240,331 |

| Interest expense, net | (27,840) | (46,820) | (52,024) | (55,270) | (55,270) |

| Income before income taxes | 123,145 | 120,088 | 139,029 | 185,061 | 185,061 |

| Provision for income taxes | (52,145) | (48,058) | (52,893) | (50,244) | (76,647) |

| Operating income | 71,000 | 72,030 | 86,136 | 134,817 | 108,414 |

| Discontinued operations | — | — | — | 10,887 | 6,831 |

| Net income | 71,000 | 72,030 | 86,136 | 145,704 | 115,245 |

| Earnings per share | 1.95 | 2.60 | 3.20 | 3.44 | 4.15 |

| Year-end share price | 17.63 | 32.75 | 35.88 | 58.50 | 71.25 |

| ($000s) | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 |

| Current assets | 177,722 | 218,156 | 267,290 | 381,672 | 401,370 |

| PP&E net | 825,178 | 916,383 | 1,072,770 | 1,494,227 | 1,791,782 |

| Other assets | 77,465 | 79,725 | 114,816 | 186,749 | 308,276 |

| Total | 1,080,365 | 1,214,264 | 1,454,876 | 2,062,648 | 2,501,428 |

| Current liabilities excl. debt | 173,948 | 222,725 | 266,837 | 391,091 | 455,227 |

| Total debt | 406,748 | 575,006 | 628,324 | 926,378 | 1,110,305 |

| Other liabilities | 86,166 | 105,028 | 137,986 | 229,174 | 307,692 |

| Shareholders' equity | 413,503 | 311,505 | 421,729 | 516,005 | 628,204 |

| Total | 1,080,365 | 1,214,264 | 1,454,876 | 2,062,648 | 2,501,428 |

| 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | |

| ROA (NI/TAopen) | 7.10% | 6.70% | 7.10% | 10.00% | 5.60% |

| ROE (NI/equityopen) | 17.00% | 17.40% | 27.70% | 34.50% | 22.30% |

| TA turnover (sales/TAopen) | 1.51 | 1.59 | 1.65 | 1.69 | 1.43 |

| Leverage (TAopen/equityopen) | 2.39 | 2.61 | 3.90 | 3.45 | 4.00 |

| Debt ratio (debt/(debt + equity) | 49.60% | 64.9% | 59.8% | 64.2% | 63.9% |

| Times interest (EBIT/interest) | 5.42 | 3.56 | 3.67 | 4.35 | 4.35 |

Note also that Marriott's working capital is a negative $4.5 million at the end of 1980 (current assets of $218.2 million less current liabilities of $222.7 million). This means that more of Marriott's financing was provided interest free by its suppliers. Finally, Marriott's stock price at year-end 1980 is $32.00 per share. And now we understand Marriott's decision not to do an open-market repurchase program. Open-market repurchases are cheaper if the stock price doesn't change much because the firm does not have to pay the premium associated with a tender offer. However, if the firm believes the stock price will rise significantly during the time a repurchase program takes, it may be cheaper for the firm to tender for the shares all at once.

By 1981, Marriott's EPS is $3.20, its ROE is 27.7%, and its net income is $86 million. Debt is at 60% of capital structure, total debt is $628 million, and working capital is at $0.5 million. Marriott's stock price at year-end is $35.88 per share.

In 1982, Marriott's EPS is $3.44; in 1983 it is $4.15. This contrasts with the maximum analysts' forecast of $3.80 per share by 1983. At the same time, Marriott's ROE in 1982 and 1983 is 34.5% and 22.3%, respectively. Net income is $145.7 million and $115.2 million, respectively. The debt level is 64.2% and 63.9% with total debt of $926.4 million and $1,110.3 million. Working capital is –$9.4 million and –$53.9 million. The stock price is $58.50/share in1982, and $71.25/share in 1983.

Let's look at these results more closely. One fact that stands out is that Marriott's percentage debt level did not come back down—it remained high. This occurred not because Wilson was wrong about future cash flows, but rather because Marriott continued buying other assets and issuing debt to finance them. For example, in 1982 Marriott bought Host International. Host International operated cafeterias at many airport terminals in the United States. Recall that Marriott was already selling food services directly to the airlines, while Host International sold food to the passengers in the terminal.12 Marriott's strategy in purchasing Host International can be summed up quickly: since Marriott is at the airport anyway, why not capture all the food business there. Marriott also bought Gino's, a regional hamburger chain, in 1982, which complemented their existing Roy Rogers hamburger/roast beef franchises. In 1985, Marriott also purchased Howard Johnson's, a national chain of restaurants.

When purchasing these assets, Marriott often issued additional debt, which is why the debt level remained high. It is important to understand the following point: if Marriott had been wrong and hadn't generated enough future cash flow, the increased debt level due to the stock repurchases might have prevented it from acting on the opportunities to buy Host International, Gino's, and Howard Johnson's.

In addition to purchasing food service assets, Marriott also started the Marriott Courtyard chain for the medium-priced hotel market. It then entered the retirement housing industry, recognizing that just as their own parents were getting older, that segment was likely to expand. Marriott also started the Marriott Residence Inns. This created a situation in which there were now different Marriotts across the street from one another. Thus, Marriott was expanding both via acquisitions and internal growth. Furthermore, it was doing this with its excess cash flow, even though it repurchased $235 million of its own stock.

To repeat and summarize, what Marriott is doing with its excess cash flow depends on what its stock price is. When the stock price is low, Marriott is buying back its stock. And when Marriott thinks its stock price is high, it uses its excess cash to buy hard assets and expand internally. By 1986, Marriott's stock price reached $37.00—but this is after a five-for-one stock split,13 or effectively $185 a share on a pre-split basis. Basically, by 1986, Marriott's stock price had increased almost ten times.

What Are You, Gary Wilson, Going to Do Next? I'm Going to Disney World!

As an aside, in 1985 Gary Wilson left Marriott to become the CFO of Disney.14 Founded by Walt Disney, the company was very profitable on the product market side but lacked good financial policies. For example, in 1985 Disney was almost entirely equity financed. The reason for this was that when Walt started out and wanted to build the first Disneyland, the bankers thought it too risky. They equated theme parks with carnivals, which had extremely poor reputations, and consequently they would not lend Disney money for this purpose. Walt bought a small piece of land and built Disneyland (in California) anyway. Afterward, all the land around the park became very valuable, but it was owned by others who profited greatly by having Disneyland nearby. All the hotels and supporting infrastructure were not owned by Disney. This is why, when Walt started building Disney World (in Florida), he bought a total of 27,743 acres at the time, virtually a whole county in Florida. As a result, the nearest hotels to the Florida theme park are all on Disney property and owned by Disney.

When Walt Disney died (in 1966), control of the firm stayed in the family (first to his brother, then to his nephew, then to his son-in-law), but the firm and stock price began to stagnate. As a consequence, Disney became a takeover target, and eventually the Bass brothers acquired control. They put Michael Eisner in charge as chairman of the company and hired Gary Wilson to be the CFO. One of the first things Gary Wilson did was to raise prices at both the theme parks and hotels. If you've ever been to Disney World, you may have stayed at one of the onsite hotels. There used to be the four hotels on the monorail with a basic price of $110 a night. They were usually sold out. Gary Wilson raised the price to $170/night. What happened to occupancy? It remained at full occupancy. In addition, Disney began building more hotels.

Admission to the theme park used to be $19 for a day pass. Gary Wilson increased the price to $28 a day. What happened to attendance? It stayed the same while revenues went up almost 50%. What Wilson understood was that the price was largely inelastic. People planned their vacation around going to Disney World, drove or flew down to Orlando, and when they got to the gates, they were not going to turn around just because it cost $9 more per day to get in.

Back to Marriott

Returning to Marriott and Wilson's old job: Was Wilson correct about inflation in 1979? He was. To review, Wilson felt that long-term interest rates were low in 1979, and he locked in these rates by issuing long-term, fixed-rate debt. In the early 1980s interest rates soared, with the prime rate hitting a peak of 21.5% in December 1980.15 With the changes in interest rates and the yield curve, Wilson also changed Marriott's interest rate structure. As Wilson noted in the 1985 Annual Report (the last one he wrote at Marriott):

Marriott minimizes capital cost and risk by optimizing the mix of floating-rate and interest-rate debt. . . . Target levels of floating-rate debt were exceeded during the early 1980s in order to employ more lower-price, floating-rate debt rather than speculate on fixed interest rates at high levels.

So, when interest rates were low and Wilson thought they were going up, Marriott issued long-term fixed-rate debt. After interest rates went up, Marriott issued short-term, floating-rate debt. When interest rates came back down, Wilson engaged in interest-rate swaps of fixed to floating rates to lock in the lower rates.

Regarding working capital, Wilson says in the 1980 Annual Report:

Negative working capital and deferred taxes provide Marriott with. . . large, interest-free source of capital. Because of disciplined capital balance sheet management and the service nature of. . . business, negative working capital will continue to increase as the company grows.

Marriott's Annual Report further says:

Marriott has no requirement for positive working capital since it principally sells services (rather than goods) for cash. Therefore, the company maintains relatively low receivable and cash balances—monetary assets that depreciate in value during inflation. Negative working capital is a source of interest-free financing.16

This essentially means that Marriott is going to continue to finance itself for free from its suppliers.

For students of corporate finance, what is important here is not that Gary Wilson was right, although that's impressive on its own. What is important is the fact that Gary Wilson thought about these interactions and understood that when the product market strategy changed, the financial strategy also needed to change. Also, as capital market conditions changed, how Marriott financed itself also needed to change.

Let's refer again to the diagram on corporate strategy discussed in Chapters 1 and 5.17 At the top of the diagram is a firm's corporate strategy (i.e., setting the corporate goals). This is not the CFO's job per se, although the CFO should participate. The firm sets its corporate strategy. For Marriott, the corporate strategy changed from owning hotels to operating hotels. Operationally, this means the firm will own a lot fewer assets. This in turn influences financial strategy, which is the second level of the diagram and part of the CFO's responsibility. The change in corporate strategy means the firm can be more aggressive with financial strategy and also more aggressive with its capital structure decisions. As far as Marriott's financial policies are concerned (illustrated on the third level of the diagram), some change and some stay the same. We assume Marriott's dividends are going to stay the same.18 Since Marriott's capital structure will change, how much debt the firm maintains and the bond rating will both change. Structuring the maturity ladder of the debt, which entails choosing the mix between long- and short-term debt, depends on what Marriott thinks interest rates will do in the future. Whether interest rates should be fixed or floating also depends on future forecasts of interest rates. Issues such as the debt covenants and whether the debt should be secured or unsecured are all issues the CFO should think about and evaluate in deciding the firm's financial strategy and policies.

SUMMARY

To summarize, this and the prior chapter are really about a firm's financial policies. One of the most important policies is the capital structure policy. The capital structure decision tries to jointly achieve a low cost of capital with a maximum share price. In fact, as we discussed, if you minimize the cost of capital, you maximize the share price. Done properly, this is one way the CFO adds value to the firm. It is also the aggressive side of financial policy. At the same time, the CFO wants to make sure the firm has access to the capital markets and can get the financing it needs for its growth. This is the supportive side of financial policy. Financial policy does not have to be just one or the other. The CFO wants to make sure that the firm has the capital to grow but, at the same time, maximizes its share price. The CFO wants financial flexibility and financial slack simultaneously.

Review: These Two Chapters Contain the Following Nine Key Concepts

- Capital structure. It is important, in thinking about capital structure, to realize that future opportunities are tied to that decision. If Wilson had been wrong, Marriott would not have been able to buy Host, Gino's, or Howard Johnson's. While that would not have destroyed the firm, it would have slowed down the growth significantly.

- Financial policies. In 1979, Marriott obtained debt financing in the domestic, unsecured, fixed-rate, long-term debt market. Why? First, Marriott is using fixed-rate, long-term debt since Gary Wilson has a view of future inflation increasing. Given this view, fixed-rate, long-term debt maximizes firm value. Next, Marriott is issuing unsecured debt because Marriott wants to be able to sell its hotel assets without having to refinance in potentially difficult times. This policy means that Marriott pays a higher interest rate—unsecured debt is more expensive than secured debt—but it increases financial flexibility and allows Marriott to sell off the assets without having to retire the debt. Then, Marriott issues in the domestic market because Marriott is not well known overseas and will have difficulty issuing there.

- Working capital. Marriott's working capital policy can be simply stated as maximizing negative working capital. As an aside, working capital across the whole economy should zero out. One firm's accounts payable are another firm's accounts receivable and vice versa. Gary Wilson is basically following the old saw of collect early, pay late.

- Dividend policy. Marriott's dividend policy is set to minimize taxes for its shareholders—the largest of which are the Marriott family. As high-taxed individuals, there's no reason for them to pay higher taxes on dividends when they can receive the return as capital gains.

- Equity. Marriott also has no preferred stock or convertible debt because of its financial policies. Since Marriott does not have a regulated capital structure, there is no reason to issue straight preferred stock when instead it can issue debt, whose interest is tax deductible. Marriott has no convertible debt because the market does not anticipate much upside to Marriott's stock price. That is, the market thinks Marriott's stock had less option value than Gary Wilson believes. If Marriott issues convertible debt, it would give Marriott a lower interest rate than straight debt, but only by a small amount because of the low option value. If a firm believes its option value is larger than the market believes, it should not issue convertible debt if it can issue straight debt. Marriott was able to issue straight debt at a reasonable rate and was not cash constrained, so they had no reason to issue convertible debt.

- Internal capital markets. In addition to financial strategy and financial policies, these two chapters show the importance of internal capital markets. This is captured by the concept of sustainable growth, which is central to the question of whether a firm finances itself internally or whether it must raise external funding.

- Excess cash. These two chapters also emphasize that there are only five things a firm can do with excess cash. Which of these five a firm should do depends on what the firm believes its future cash flows and stock price will be. The five things to do with cash contain both financial solutions (i.e., repurchase stock, pay down debt, or increase dividends) as well as product market solutions (i.e., grow faster internally or acquire external assets). In Marriott's situation, when Wilson thought the stock price was low, he used the extra cash to buy back stock. When he thought the stock price was high, he did not buy back stock but rather bought other assets.

- Asymmetric information. These chapters also demonstrate the importance of asymmetric information. When firms announce tender offers, the stock market, on average, increases the stock price. When a firm announces an open-market share repurchase, the market also increases the price, but not as much as for a tender offer. This is due to the market's belief that a tender offer, where the firm is willing to pay an immediate premium, is stronger evidence that a firm's share price is going up and it's going up soon. When a firm issues equity, the market generally lowers the stock price. It's as if the market says, “If the firm is selling equity, it must need the money, or the firm believes its stock price is high.” If you ask a CEO “Why is the firm not currently issuing equity?” the answer is usually, “The price is not high enough.” If one day the CEO announces, “Oh, by the way, we're issuing equity,” the market interprets this as information. Dividend policy can also be interpreted through this lens of asymmetric information. The next chapter includes a longer discussion of asymmetric information and market signaling.

- Interactions. There is a relationship between financing decisions and investment decisions. A policy change can be a good investment decision and/or a good financing decision. Often, policy changes affect both, and we should consider them both together. In this case, the decision to repurchase the stock and issue debt is both a financing decision that affects the capital structure and an investment decision that determines the price used to repurchase the shares. We conclude this was probably a good financing decision, although it was a dynamic decision. Wilson overshot his optimal capital structure with the anticipation that the cash flow would bring it back down. We also conclude that the investment decision was a good one, as $23.50 was subsequently shown to be a cheap price to pay for Marriott stock.

Postscript

In 1993 Marriott decided to divide itself into two firms: Marriott International—where it put most of the hotel properties, and Host Marriott—where it put everything else.19 At that time, the hotel properties were operating better than the rest of Marriott. Marriott took most of the firm's debt and assigned it to Host Marriott, leaving Marriott International largely unlevered. This was very controversial at the time, and at least one director resigned. The two divided parts of the firm were called good Marriott and bad Marriott in the press. Good Marriott contained the best operating companies with low debt. Bad Marriott was the weaker operating company, which assumed most of the debt. Marriott stock was also split into two. The split was essentially a stock dividend, with current stockholders getting shares of both Marriott International and Host Marriott.

Coming Attractions

Where are we headed next? In the next two chapters, we are going to discuss these issues again with different companies: AT&T and MCI. We're going to look at AT&T and its financial policies before it was deregulated and then we're going to discuss its policies and what they should be after deregulation. Then we're going to look at MCI before and after deregulation.