page 28

CHAPTER

TWO

2

Organization Strategy and Project Selection

page 29

A vision without a strategy remains an illusion.

—Lee Bolman, professor of leadership, University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Strategy is fundamentally deciding how the organization will compete. Organizations use projects to convert strategy into new products, services, and processes needed for success. For example, Intel’s major strategy is one of differentiation. Intel relies on projects to create specialty chips for products other than computers, such as autos, security, cell phones, and air controls. Another strategy is to reduce project cycle times. Procter and Gamble, NEC, General Electric, and AT&T have reduced their cycle times by 20–50 percent. Toyota and other auto manufacturers are now able to design and develop new cars in two to three years instead of five to seven. Projects and project management play the key role in supporting strategic goals. It is vital for project managers to think and act strategically.

Aligning projects with the strategic goals of the organization is crucial for business success. Today’s economic climate is unprecedented by rapid changes in technology, page 30global competition, and financial uncertainty. These conditions make strategy/project alignment even more essential for success.

The larger and more diverse an organization, the more difficult it is to create and maintain a strong link between strategy and projects. How can an organization ensure this link? The answer requires integration of projects with the strategic plan. Integration assumes the existence of a strategic plan and a process for prioritizing projects by their contribution to the plan. A key factor to ensure the success of integrating the plan with projects is an open and transparent selection process for all participants to review.

This chapter presents an overview of the importance of strategic planning and the process for developing a strategic plan. Typical problems encountered when strategy and projects are not linked are noted. A generic methodology that ensures integration by creating strong linkages of project selection and priority to the strategic plan is then discussed. The intended outcomes are clear organization focus, best use of scarce organization resources (people, equipment, capital), and improved communication across projects and departments.

2.1 Why Project Managers Need to Understand Strategy

Project management historically has been preoccupied solely with the planning and execution of projects. Strategy was considered to be under the purview of senior management. This is old-school thinking. New-school thinking recognizes that project management is at the apex of strategy and operations. Shenhar speaks to this issue when he states, “It is time to expand the traditional role of the project manager from an operational to a more strategic perspective. In the modern evolving organization, project managers will be focused on business aspects, and their role will expand from getting the job done to achieving the business results and winning in the marketplace.”1

There are two main reasons project managers need to understand their organization’s mission and strategy. The first reason is so they can make appropriate decisions and adjustments. For example, how a project manager would respond to a suggestion to modify the design of a product to enhance performance will vary depending upon whether his company strives to be a product leader through innovation or to achieve operational excellence through low-cost solutions. Similarly, how a project manager would respond to delays may vary depending upon strategic concerns. A project manager will authorize overtime if her firm places a premium on getting to the market first. Another project manager will accept the delay if speed is not essential.

The second reason project managers need to understand their organization’s strategy is so they can be effective project advocates. Project managers have to be able to demonstrate to senior management how their project contributes to their firm’s mission in order to garner their continued support. Project managers need to be able to explain to stakeholders why certain project objectives and priorities are critical in order to secure buy-in on contentious trade-off decisions. Finally, project managers need to explain why the project is important to motivate and empower the project team (Brown, Hyer, & Ettenson, 2013).

page 31

For these reasons project managers will find it valuable to have a keen understanding of strategic management and project selection processes, which are discussed next.

2.2 The Strategic Management Process: An Overview

Strategic management is the process of assessing “what we are” and deciding and implementing “what we intend to be and how we are going to get there.” Strategy describes how an organization intends to compete with the resources available in the existing and perceived future environment. Two major dimensions of strategic management are responding to changes in the external environment and allocating the firm’s scarce resources to improve its competitive position. Constant scanning of the external environment for changes is a major requirement for survival in a dynamic competitive environment. The second dimension is the internal responses to new action programs aimed at enhancing the competitive position of the firm. The nature of the responses depends on the type of business, environment volatility, competition, and the organizational culture.

Strategic management provides the theme and focus of the future direction of the organization. It supports consistency of action at every level of the organization. It encourages integration because effort and resources are committed to common goals and strategies. See Snapshot from Practice 2.1: Does IBM’s Watson’s Jeopardy Project Represent a Change in Strategy? Strategic management is a continuous, iterative process aimed at developing an integrated and coordinated long-term plan of action. It positions the organization to meet the needs and requirements of its customers for the long term. With the long-term position identified, objectives are set, and strategies are developed to achieve objectives and then translated into actions by implementing projects.

Strategy can decide the survival of an organization. Most organizations are successful in formulating strategies for the course(s) they should pursue. However, the problem in many organizations is implementing strategies—that is, making them happen. Integration of strategy formulation and implementation often does not exist.

The components of strategic management are closely linked, and all are directed toward the future success of the organization. Strategic management requires strong links among mission, goals, objectives, strategy, and implementation. The mission gives the general purpose of the organization. Goals give global targets within the mission. Objectives give specific targets to goals. Objectives give rise to the formulation of strategies to reach objectives. Finally, strategies require actions and tasks to be implemented. In most cases the actions to be taken represent projects. Figure 2.1 shows a schematic of the strategic management process and major activities required.

FIGURE 2.1 Strategic Management Process

Four Activities of the Strategic Management Process

The typical sequence of activities of the strategic management process is outlined here; a description of each activity then follows.

Review and define the organizational mission.

Analyze and formulate strategies.

Set objectives to achieve strategies.

Implement strategies through projects.

page 32

page 33

Review and Define the Organizational Mission

The mission identifies “what we want to become,” or the raison d’être. Mission statements identify the scope of the organization in terms of its product or service. A written mission statement provides focus for decision making when shared by organizational managers and employees. Everyone in the organization should be keenly aware of the organization’s mission. For example, at one large consulting firm, partners who fail to recite the mission statement on demand are required to buy lunch. The mission statement communicates and identifies the purpose of the organization to all stakeholders. Mission statements can be used for evaluating organization performance.

Traditional components found in mission statements are major products and services, target customers and markets, and geographical domain. In addition, statements frequently include organizational philosophy, key technologies, public image, and contribution to society. Including such factors in mission statements relates directly to business success.

page 34

Mission statements change infrequently. However, when the nature of the business changes or shifts, revised mission and strategy statements may be required.

More specific mission statements tend to give better results because of a tighter focus. Mission statements decrease the chance of false directions by stakeholders. For example, compare the phrasing of the following mission statements:

Provide hospital design services.

Provide data mining and analysis services.

Provide information technology services.

Provide high-value products to our customer.

Clearly the first two statements leave less chance for misinterpretation than the others. A rule-of-thumb test for a mission statement is that, if the statement can be anybody’s mission statement, it will not provide the guidance and focus intended. The mission sets the parameters for developing objectives.

Analyze and Formulate Strategies

Formulating strategy answers the question of what needs to be done to reach objectives. Strategy formulation includes determining and evaluating alternatives that support the organization’s objectives and selecting the best alternative. The first step is a realistic evaluation of the past and current position of the enterprise. This step typically includes an analysis of “who are the customers” and “what are their needs as they (the customers) see them.”

The next step is an assessment of the internal and external environments. What are the internal strengths and weaknesses of the enterprise? Examples of internal strengths or weaknesses are core competencies, such as technology, product quality, management talent, low debt, and dealer networks. Managers can alter internal strengths and weaknesses. Opportunities and threats usually represent external forces for change such as technology, industry structure, and competition. Competitive benchmarking tools are sometimes used to assess current and future directions. Opportunities and threats are the flip sides of each other. That is, a threat can be perceived as an opportunity, or vice versa. Examples of perceived external threats are a slowing of the economy, a maturing life cycle, exchange rates, and government regulation. Typical opportunities are increasing demand, emerging markets, and demographics. Managers or individual firms have limited opportunities to influence such external environmental factors; however, notable exceptions have been new technologies such as Apple using the iPod to create a market to sell music. The keys are to attempt to forecast fundamental industry changes and stay in a proactive mode rather than a reactive one. This assessment of the external and internal environments is known as the SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats).

From this analysis, critical issues and strategic alternatives are identified. Critical analysis of the strategies includes asking questions: Does the strategy take advantage of our core competencies? Does the strategy exploit our competitive advantage? Does the strategy maximize meeting customers’ needs? Does the strategy fit within our acceptable risk range? These strategic alternatives are winnowed down to a critical few that support the basic mission.

Strategy formulation ends with cascading objectives or projects assigned to lower divisions, departments, or individuals. Formulating strategy might range around 20 percent of management’s effort, while determining how strategy will be implemented might consume 80 percent.

page 35

Set Objectives to Achieve Strategies

Objectives translate the organization strategy into specific, concrete, measurable terms. Organizational objectives set targets for all levels of the organization. Objectives pinpoint the direction managers believe the organization should move toward. Objectives answer in detail where a firm is headed and when it is going to get there. Typically objectives for the organization cover markets, products, innovation, productivity, quality, finance, profitability, employees, and consumers. In every case, objectives should be as operational as possible. That is, objectives should include a time frame, be measurable, be an identifiable state, and be realistic. Doran (1981) created the memory device shown in Exhibit 2.1, which is useful when writing objectives.

EXHIBIT 2.1 Characteristics of Objectives

| S | Specific | Be specific in targeting an objective | ||||

| M | Measurable | Establish a measurable indicator(s) of progress | ||||

| A | Assignable | Make the objective assignable to one person for completion | ||||

| R | Realistic | State what can realistically be done with available resources | ||||

| T | Time related | State when the objective can be achieved, that is, duration |

Each level below the organizational objectives should support the higher-level objectives in more detail; this is frequently called cascading of objectives. For example, if a firm making leather luggage sets an objective of achieving a 40 percent increase in sales through a research and development strategy, this charge is passed to the Marketing, Production, and R&D Departments. The R&D Department accepts the firm’s strategy as their objective, and their strategy becomes the design and development of a new “pull-type luggage with hidden, retractable wheels.” At this point the objective becomes a project to be implemented—to develop the retractable-wheel luggage for market within six months within a budget of $200,000. In summary, organizational objectives drive projects.

Implement Strategies through Projects

Implementation answers the question of how strategies will be realized, given available resources. The conceptual framework for strategy implementation lacks the structure and discipline found in strategy formulation. Implementation requires action and task completion; the latter frequently means mission-critical projects. Therefore, implementation must include attention to several key areas.

First, task completion requires resources. Resources typically represent funds, people, management talents, technological skills, and equipment. Frequently, implementation of projects is treated as an “addendum” rather than an integral part of the strategic management process. However, multiple objectives place conflicting demands on organizational resources. Second, implementation requires a formal and informal organization that complements and supports strategy and projects. Authority, responsibility, and performance all depend on organization structure and culture. Third, planning and control systems must be in place to be certain project activities necessary to ensure strategies are effectively performed. Fourth, motivating project contributors will be a major factor for achieving project success. Finally, areas receiving more attention in recent years are portfolio management and prioritizing projects. Although the strategy implementation process is not as clear as strategy formulation, all managers realize that without implementation, success is impossible. page 36Although the four major steps of the strategic management process have not been altered significantly over the years, the view of the time horizon in the strategy formulation process has been altered radically in the last two decades. Global competition and rapid innovation require being highly adaptive to short-run changes while being consistent in the longer run.

2.3 The Need for a Project Priority System

Implementation of projects without a strong priority system linked to strategy creates problems. Three of the most obvious problems are discussed in this section. A priority-driven project portfolio system can go a long way to reduce, or even eliminate, the impact of these problems.

Problem 1: The Implementation Gap

In many organizations, top management formulate strategy and leave strategy implementation to functional managers. Within these broad constraints, more detailed strategies and objectives are developed by the functional managers. The fact that these objectives and strategies are made independently at different levels by functional groups within the organization hierarchy causes manifold problems.

Following are some symptoms of organizations struggling with strategy disconnect and unclear priorities.

Conflicts frequently occur among functional managers and cause lack of trust.

Frequent meetings are called to establish or renegotiate priorities.

People frequently shift from one project to another, depending on current priority. Employees are confused about which projects are important.

People are working on multiple projects and feel inefficient.

Resources are not adequate.

Because clear linkages do not exist between strategy and action, the organizational environment becomes dysfunctional, confused, and ripe for ineffective implementation of organization strategy and, thus, of projects. The implementation gap is the lack of understanding and consensus of organization strategy among top and middle-level managers.

A scenario the authors have seen repeated several times follows. Top management pick their top 20 projects for the next planning period, without priorities. Each functional department—Marketing, Finance, Operations, Engineering, Information Technology, and Human Resources—selects projects from the list. Unfortunately, independent department priorities across projects are not homogenous. A project that rates first in the IT Department can rate 10th in the Finance Department. Implementation of the projects represents conflicts of interest, with animosities developing over organizational resources.

If this condition exists, how is it possible to implement strategy effectively? The problem is serious. One study found that only about 25 percent of Fortune 500 executives believe there is a strong linkage, consistency, and/or agreement between the strategies they formulate and implementation. In a study of Deloitte Consulting, MacIntyre reports, “Only 23 percent of nearly 150 global executives considered their project portfolios aligned with the core business.”2

page 37

Problem 2: Organization Politics

Politics exist in every organization and can have a significant influence on which projects receive funding and high priority. This is especially true when the criteria and process for selecting projects are ill-defined and not aligned with the mission of the firm. Project selection may be based not so much on facts and sound reasoning as on the persuasiveness and power of people advocating projects.

The term sacred cow is often used to denote a project that a powerful, high-ranking official is advocating. Case in point, a marketing consultant confided that he was once hired by the marketing director of a large firm to conduct an independent, external market analysis for a new product the firm was interested in developing. His extensive research indicated that there was insufficient demand to warrant the financing of this new product. The marketing director chose to bury the report and made the consultant promise never to share this information with anyone. The director explained that this new product was the “pet idea” of the new CEO, who saw it as his legacy to the firm. The director went on to describe the CEO’s irrational obsession with the project and how he referred to it as his “new baby.” Like a parent fiercely protecting his child, the marketing director believed that he would lose his job if such critical information ever became known.

Project sponsors play a significant role in the selection and successful implementation of product innovation projects. Project sponsors are typically high-ranking managers who endorse and lend political support for the completion of a specific project. They are instrumental in winning approval of the project and in protecting the project during the critical development stage. The importance of project sponsors should not be taken lightly. For example, a PMI global survey of over 1,000 project practitioners and leaders over a variety of industries found those organizations having active sponsors on at least 80 percent of their projects/programs have a success rate of 75 percent, 11 percentage points above the survey average of 64 percent. Many promising projects have failed to succeed due to lack of strong sponsorship.3

The significance of corporate politics can be seen in the ill-fated ALTO computer project at Xerox during the mid-1970s.4 The project was a tremendous technological success; it developed the first workable mouse, the first laser printer, the first user-friendly software, and the first local area network. All of these developments were five years ahead of their nearest competitor. Over the next five years this opportunity to dominate the nascent personal computer market was squandered because of internal in-fighting at Xerox and the absence of a strong project sponsor. (Apple’s MacIntosh computer was inspired by many of these developments.)

Politics can play a role not only in project selection but also in the aspirations behind projects. Individuals can enhance their power within an organization by managing extraordinary and critical projects. Power and status naturally accrue to successful innovators and risk takers rather than to steady producers. Many ambitious managers pursue high-profile projects as a means for moving quickly up the corporate ladder.

Many would argue that politics and project management should not mix. A more proactive response is that projects and politics invariably mix and that effective project page 38managers recognize that any significant project has political ramifications. Likewise, top management need to develop a system for identifying and selecting projects that reduces the impact of internal politics and fosters the selection of the best projects for the firm.

Problem 3: Resource Conflicts and Multitasking

Most projects operate in a multiproject environment. This environment creates the problems of project interdependency and the need to share resources. For example, what would be the impact on the labor resource pool of a construction company if it should win a contract it would like to bid on? Will existing labor be adequate to deal with the new project—given the completion date? Will current projects be delayed? Will subcontracting help? Which projects will have priority? Competition among project managers can be contentious. All project managers seek to have the best people for their projects. The problems of sharing resources and scheduling resources across projects grow exponentially as the number of projects rises. In multiproject environments the stakes are higher and the benefits or penalties for good or bad resource scheduling become even more significant than in most single projects (Mortensen & Gardner, 2017).

Resource sharing also leads to multitasking. Multitasking involves starting and stopping work on one task to go and work on another project, then returning to the work on the original task. People working on several tasks concurrently are far less efficient, especially where conceptual or physical shutdown and start-up are significant. Multitasking adds to delays and costs. Changing priorities exacerbate the multitasking problems even more. Likewise, multitasking is more evident in organizations that have too many projects for the resources they command.

The number of small and large projects in a portfolio almost always exceeds the available resources. This capacity overload inevitably leads to confusion and inefficient use of scarce organizational resources. The presence of an implementation gap, of power politics, and of multitasking adds to the problem of which projects are allocated resources first. Employee morale and confidence suffer because it is difficult to make sense of an ambiguous system. A multiproject organizational environment faces major problems without a priority system that is clearly linked to the strategic plan. See Exhibit 2.2, which lists a few key benefits of Project Portfolio Management; the list could easily be extended.

EXHIBIT 2-2

Benefits of Project Portfolio Management

|

2.4 Project Classification

Many organizations find they have three basic kinds of projects in their portfolio: compliance (emergency—must do), operational, and strategic projects. (See Figure 2.2.) Compliance projects are typically those needed to meet regulatory conditions required to operate in a region; hence, they are called “must do” projects. Emergency projects, page 39such as building an auto parts factory destroyed by a tsunami or recovering a crashed network, are examples of must do projects. Compliance and emergency projects usually have penalties if they are not implemented.

FIGURE 2.2

Project Classification

Operational projects are those that are needed to support current operations. These projects are designed to improve the efficiency of delivery systems, reduce product costs, and improve performance. Some of these projects, given their limited scope and cost, require only immediate manager approval, while bigger, more expensive projects need extensive review. Choosing to install a new piece of equipment is an example of the latter, while modifying a production process is an example of the former. Total quality management (TQM) projects are examples of operational projects.

Strategic projects are those that directly support the organization’s long-run mission. They frequently are directed toward increasing revenue or market share. Examples of strategic projects are new products, new technologies, research, and development.5

Frequently these three classifications are further decomposed by product type, organization divisions, and functions that will require different criteria for project selection. For example, the same criteria for the Finance or Legal Division would not apply to the Information Technology Department. This often requires different project selection criteria within the basic three classifications of strategic, operational, and compliance projects.

2.5 Phase Gate Model

Before we delve into the intricacies of project selection, we need to put this process in perspective. The selection process is the first part of the management system that spans the lifetime of the project. This system has been described as a series of gates that a project must pass through in order to be completed.6 The purpose is to ensure that the organization is investing time and resources on worthwhile projects that contribute to its mission and strategy. Each gate is associated with a project phase and represents a decision point. A gate can lead to three possible outcomes: page 40go (proceed), kill (cancel), or recycle (revise and resubmit). Figure 2.3 captures the phase gate model.

FIGURE 2.3

Phase Gate Process Diagram

The first gate is invisible. It occurs inside the head of a person who has an idea for a project and must decide whether it is worth investing the time and effort to submit a formal proposal. This decision may be a gut reaction or involve informal research. Such research might include bouncing the idea off of colleagues or doing online research. It helps if the organization has a transparent project selection process where objectives and requirements for approval are well known.

If the person believes his idea is worthwhile, then a project proposal is submitted conforming to the selection guidelines of the firm. Project proposals, as you will see, include such items as project objectives, business case, estimated costs, return on investment, risks, and resource requirements. Beyond the basic question of whether the proposal makes sense, management assesses how the project outcomes will contribute to the mission and strategy of the firm. For example, page 41what strategic objectives does the project address? A second key question is “How well does the project fit with other projects?” Will it interfere with other, more important projects? Here the final question is whether this project is worthy of more planning.

If the preliminary proposal is approved, then a project manager and staff are assigned to develop a more comprehensive implementation plan. The preliminary proposal is revised and expanded. The plan now includes detailed information regarding schedule, costs, resource requirements, risk management, and so forth. Not only is the proposal assessed again in terms of strategic importance, but the implementation plan is scrutinized. Does the plan make sense? Do the numbers add up? Is it worth the risk? How much confidence is there in the plan? If affirmative, the green light is given to launch the project.

Once the project is under way there will likely be one or more progress reviews. The main purpose of progress review is to assess performance and determine what, if any, adjustments should be made. In some cases, the decision is made to cancel, or “kill,” a project due to poor performance or lack of relevancy.

The last gate is the finish line. Here the necessary customer acceptance has been achieved and management has signed off on the fulfillment of project requirements. This stage includes a project audit to assess project success as well as identifying key lessons learned.

It should be noted that this is the basic phase gate model. For many firms, projects will go through a series of internal escalated reviews before they obtain final approval. This is especially true for projects that have high risks, have high costs, and/or demand scarce resources. Likewise, the number of progress gates will vary depending upon the length and importance of the projects. For example, a three-year U.S. Department of Defense project will have progress reviews every six months.

The remainder of this chapter focuses on gates 2 and 3, which lead to a project being green lighted. Performance data to assess progress are the subject of Chapter 13, while the final gate is addressed in Chapter 14.

2.6 Selection Criteria

Selection criteria are typically identified as financial and nonfinancial. A short description of each is given next, followed by a discussion of their use in practice.

Financial Criteria

For most managers financial criteria are the preferred method to evaluate projects. These models are appropriate when there is a high level of confidence associated with estimates of future cash flows. Two models and examples are demonstrated in this section—payback and net present value (NPV).

Project A has an initial investment of $700,000 and projected cash inflows of $225,000 for 5 years.

Project B has an initial investment of $400,000 and projected cash inflows of $110,000 for 5 years.

1. The payback model measures the time it will take to recover the project investment. Shorter paybacks are more desirable. Payback is the simplest and most widely page 42used model. Payback emphasizes cash flows, a key factor in business. Some managers use the payback model to eliminate unusually risky projects (those with lengthy payback periods). The major limitations of payback are that it ignores the time value of money, assumes cash inflows for the investment period (and not beyond), and does not consider profitability. The payback formula is

Exhibit 2.3A compares the payback for project A and project B. The payback for project A is 3.1 years and for project B is 3.6 years. Using the payback method, both projects are acceptable, since both return the initial investment in less than five years and have returns on the investment of 32.1 and 27.5 percent. Payback provides especially useful information for firms concerned with liquidity and having sufficient resources to manage their financial obligations.

EXHIBIT 2.3A

Example Comparing Two Projects Using Payback Method

Microsoft Excel

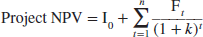

2. The net present value (NPV) model uses management’s minimum desired rate of return (discount rate, for example, 15 percent) to compute the present value of all net cash inflows. If the result is positive (the project meets the minimum desired rate page 43of return), it is eligible for further consideration. If the result is negative, the project is rejected. Thus, higher positive NPVs are desirable. Excel uses this formula:

where

| I0 | = | Initial investment (since it is an outflow, the number will be negative) |

| Ft | = | Net cash inflow for period t |

| k | = | Required rate of return |

| n | = | number of years |

Exhibit 2.3B presents the NPV model using Microsoft Excel software. The NPV model accepts project A, which has a positive NPV of $54,235. Project B is rejected, since the NPV is negative $31,263. Compare the NPV results with the payback results. The NPV model is more realistic because it considers the time value of money, cash flows, and profitability.

EXHIBIT 2.3B

Example Comparing Two Projects Using Net Present Value Method

Microsoft Excel

In the NPV model, the discount rate (return on investment [ROI] hurdle rate) can differ for different projects. For example, the expected ROI on strategic projects is frequently set higher than operational projects. Similarly, ROIs can differ for riskier versus safer projects. The criteria for setting the ROI hurdle rate should be clear and applied consistently.

Unfortunately, pure financial models fail to include many projects where financial return is impossible to measure and/or other factors are vital to the accept or reject decision. One research study by Foti (2003) showed that companies using predominantly financial models to prioritize projects yielded unbalanced portfolios and projects that were not strategically oriented.

Nonfinancial Criteria

Financial return, while important, does not always reflect strategic importance. The past saw firms become overextended by diversifying too much. Now the prevailing thinking is that long-term survival is dependent upon developing and maintaining core competencies. Companies have to be disciplined in saying no to potentially profitable projects that are outside the realm of their core mission. This requires other criteria be considered beyond direct financial return. For example, a firm may support projects that do not have high profit margins for other strategic reasons, including

To capture larger market share.

To make it difficult for competitors to enter the market.

To develop an enabler product, which by its introduction will increase sales in more profitable products.

To develop core technology that will be used in next-generation products.

To reduce dependency on unreliable suppliers.

To prevent government intervention and regulation.

Less tangible criteria may also apply. Organizations may support projects to restore corporate image or enhance brand recognition. Many organizations are committed to corporate citizenship and support community development projects.

Two Multi-Criteria Selection Models

Since no single criterion can reflect strategic significance, portfolio management requires multi-criteria screening models. Two models, the checklist and multi-weighted scoring models, are described next.

page 44

Checklist Models

The most frequently used method in selecting projects has been the checklist. This approach basically uses a list of questions to review potential projects and to determine their acceptance or rejection. Several of the typical questions found in practice are listed in Exhibit 2.4.

EXHIBIT 2.4 Sample Selection Questions Used in Practice

| Topic | Question |

| Strategy/alignment | What specific organization strategy does this project align with? |

| Driver | What business problem does the project solve? |

| Sponsorship | Who is the project sponsor? |

| Risk | What is the impact of not doing this project? |

| Risk | How risky is the project? |

| Benefits, value, ROI | What is the value of the project to this organization? |

| Benefits, value, ROI | When will the project show results? |

| Objectives | What are the project objectives? |

| Organization culture | Is our organizational culture right for this type of project? |

| Resources | Will internal resources be available for this project? |

| Schedule | How long will this project take? |

| Finance/portfolio | What is the estimated cost of the project? |

| Portfolio | How does this project interact with current projects? |

A justification of checklist models is that they allow great flexibility in selecting among many different types of projects and are easily used across different divisions and locations. Although many projects are selected using some variation of the checklist approach, this approach has serious shortcomings. Its major shortcomings are that it fails to answer the relative importance or value of a potential project to the organization and fails to allow for comparison with other potential projects. Each potential project will have a different set of positive and negative answers. How do you compare? Ranking and prioritizing projects by their importance is difficult, if not impossible. This approach also leaves the door open to the potential opportunity for power plays, politics, and other forms of manipulation. To overcome these serious shortcomings, experts recommend the use of a multi-weighted scoring model to select projects, which is examined next.

Multi-Weighted Scoring Models

A weighted scoring model typically uses several weighted selection criteria to evaluate project proposals. Weighted scoring models generally include qualitative and/or quantitative criteria. Each selection criterion is assigned a weight. Scores are assigned to each criterion for the project, based on its importance to the project being evaluated. The weights and scores are multiplied to get a total weighted score for the project. Using these multiple screening criteria, projects can then be compared using the weighted score. Projects with higher-weighted scores are considered better.

Selection criteria need to mirror the critical success factors of an organization. For example, 3M set a target that 25 percent of the company’s sales would come from products fewer than four years old versus the old target of 20 percent. Their priority system for project selection strongly reflects this new target. On the other hand, failure to pick the right factors will render the screening process useless in short order. See Snapshot from Practice 2.2: Crisis IT.

page 45

Figure 2.4 represents a project scoring matrix using some of the factors found in practice. The screening criteria selected are shown across the top of the matrix (e.g., stay within core competencies . . . ROI of 18 percent plus). Management weights each criterion (a value of 0 to a high of, say, 3) by its relative importance to the organization’s objectives and strategic plan. Project proposals are then submitted to a project priority team or project office.

FIGURE 2.4

Project Screening Matrix

Each project proposal is then evaluated by its relative contribution/value added to the selected criteria. Values of 0 to a high of 10 are assigned to each criterion for each project. This value represents the project’s fit to the specific criterion. For example, project 1 appears to fit well with the strategy of the organization, since it is given a value of 8. Conversely, project 1 does nothing to support reducing defects (its value is 0). Finally, this model applies the management weights to each criterion by importance using a value of 1 to 3. For example, ROI and strategic fit have a weight of 3, while urgency and core competencies have weights of 2. Applying the weight to each criterion, the priority team derives the weighted total points for each project. page 46For example, project 5 has the highest value of 102 [(2 × 1) + (3 × 10) + (2 × 5) + (2.5 × 10) + (1 × 0) + (1 × 8) + (3 × 9) = 102] and project 2 has a low value of 27. If the resources available create a cutoff threshold of 50 points, the priority team would eliminate projects 2 and 4. Project 5 would receive first priority, project n second, and so on. In rare cases where resources are severely limited and project proposals are similar in weighted rank, it is prudent to pick the project placing less demand on resources. Weighted multi-criteria models similar to this one are rapidly becoming the dominant choice for prioritizing projects.

At this point in the discussion it is wise to stop and put things into perspective. While selection models like the one in this section may yield numeric solutions to project selection decisions, models should not make the final decisions—the people using the models should. No model, no matter how sophisticated, can capture the total reality it is meant to represent. Models are tools for guiding the evaluation process so that the decision makers will consider relevant issues and reach a meeting of the minds as to which projects should be supported. This is a much more subjective process than calculations suggest.

2.7 Applying a Selection Model

Project Classification

It is not necessary to have exactly the same criteria for the different types of projects discussed in the previous section (strategic and operations). However, experience shows most organizations use similar criteria across all types of projects, with perhaps one or two criteria specific to the type of project—for example, strategic breakthrough versus operational.

page 47

Regardless of criteria differences among different types of projects, the most important criterion for selection is the project’s fit to the organization strategy. Therefore, this criterion should be consistent across all types of projects and carry a high priority relative to other criteria. This uniformity across all priority models used can keep departments from suboptimizing the use of organizational resources. Project proposals should be classified by type so the appropriate criteria can be used to evaluate them.

Selecting a Model

In the past, financial criteria were used almost to the exclusion of other criteria. However, in the last two decades we have witnessed a dramatic shift to include multiple criteria in project selection. Concisely put, profitability alone is simply not an adequate measure of contribution; however, it is still an important criterion, especially for projects that enhance revenue and market share such as breakthrough R&D projects.

Today senior management are interested in identifying the potential mix of projects that will yield the best use of human and capital resources to maximize return on investment in the long run. Factors such as researching new technology, public image, ethical position, protection of the environment, core competencies, and strategic fit might be important criteria for selecting projects. Weighted scoring criteria seem the best alternative to meet this need.

Weighted scoring models result in bringing projects into closer alignment with strategic goals. If the scoring model is published and available to everyone in the organization, some discipline and credibility are attached to the selection of projects. The number of wasteful projects using resources is reduced. Politics and sacred cow projects are exposed. Project goals are more easily identified and communicated using the selection criteria as corroboration. Finally, using a weighted scoring approach helps project managers understand how their project was selected, how their project contributes to organization goals, and how it compares with other projects. Project selection is one of the most important decisions guiding the future success of an organization.

Criteria for project selection are where the power of a portfolio starts to manifest itself. New projects are aligned with the strategic goals of the organization. With a clear method in place for selecting projects, project proposals can be solicited.

Sources and Solicitation of Project Proposals

As you would guess, projects should come from anyone who believes her project will add value to the organization. However, many organizations restrict proposals from specific levels or groups within the organization. This could be an opportunity lost. Good ideas are not limited to certain types or classes of organization stakeholders.

Figure 2.5A provides an example of a proposal form for an automatic vehicular tracking (Automatic Vehicle Location) public transportation project. Figure 2.5B presents a preliminary risk analysis for a 500-acre wind farm. Many organizations use risk analysis templates to gain a quick insight into a project’s inherent risks. Risk factors depend on the organization and type of projects. This information is useful in balancing the project portfolio and identifying major risks when executing the project. Project risk analysis is the subject of Chapter 7.

FIGURE 2-5A

A Proposal Form for an Automatic Vehicular Tracking (AVL) Public Transportation Project

FIGURE 2.5B

Risk Analysis for a 500-Acre Wind Farm

In some cases organizations will solicit ideas for projects when the knowledge requirements for the project are not available in the organization. Typically the organization will issue a Request for Proposal (RFP) to contractors/vendors with page 48adequate experience to implement the project. In one example, a hospital published an RFP that asked for a bid to design and build a new operating room that used the latest technology. Several architecture firms submitted bids to the hospital. The bids for the project were evaluated internally against other potential projects. When the project was accepted as a go, other criteria were used to select the best-qualified bidder.

page 49

Ranking Proposals and Selection of Projects

Culling through so many proposals to identify those that add the most value requires a structured process. Figure 2.6 shows a flow chart of a screening process beginning with the submission of a formal project proposal.7 A senior priority team evaluates each proposal in terms of feasibility, potential contribution to strategic objectives, and fit within a portfolio of current projects. Given selection criteria and current portfolio, the priority team rejects or accepts the project.

FIGURE 2.6

Project Screening Process

If the project is approved, a project manager and staff are assigned to develop a detailed implementation plan. Once completed, the proposal with implementation plan is reviewed a second time. Veteran project managers are assigned to the priority team. They draw on their experience to identify potential flaws in the plan. Strategic value is again assessed, but within the context of a more detailed plan. page 50Variances between what was estimated in the initial proposal and final estimates based on more complete research/planning are examined. If significant negative differences are found (e.g., the initial total cost estimate was $10 million but the final estimate was $12 million, or the end product will no longer include a key feature), the proposal will likely be deferred to more senior management to decide whether the project should still be approved. Otherwise, the project is approved and priority assigned. Management issues a charter authorizing the project manager to form a project team and secure resources to begin project work.

Figure 2.7 is a partial example of an evaluation form used by a large company to prioritize and select new projects. The form distinguishes between must and want objectives. If a project does not meet designated “must” objectives, it is not considered and is removed from consideration. Organization (or division) objectives have been ranked and weighted by their relative importance—for example, “Improve external customer service” carries a relative weight of 83 when compared to other want objectives. The want objectives are directly linked to objectives found in the strategic plan.

FIGURE 2.7

Priority Screening Analysis

Impact definitions represent a further refinement to the screening system. They are developed to gauge the predicted impact a specific project would have on meeting a particular objective. A numeric scheme is created and anchored by defining criteria. To illustrate how this works, let’s examine the $5 million in new sales objective. A “0” is assigned if the project will have no impact on sales or less than $100,000, page 51a “1” is given if predicted sales are more than $100,000 but less than $500,000, a “2” if greater than $500,000. These impact assessments are combined with the relative importance of each objective to determine the predicted overall contribution of a project to strategic objectives. For example, project 26 creates an opportunity to fix field problems, has no effect on sales, and will have major impact on customer service. On these three objectives, project 26 would receive a score of 265 [99 + 0 + (2 × 83)]. Individual weighted scores are totaled for each project and are used to prioritize projects.

Responsibility for Prioritizing

Senior management should be responsible for prioritizing projects. It requires more than a blessing. Management will need to rank and weigh, in concrete terms, the objectives and strategies they believe are most critical to the organization. This public declaration of commitment can be risky if the ranked objectives later prove to be poor page 52choices, but setting the course for the organization is top management’s job. The good news is, if management is truly trying to direct the organization to a strong future position, a good project priority system supports their efforts and develops a culture in which everyone is contributing to the goals of the organization.

2.8 Managing the Portfolio System

Managing the portfolio takes the selection system one step higher in that the merits of a particular project are assessed within the context of existing projects. At the same time it involves monitoring and adjusting selection criteria to reflect the strategic focus of the organization. This requires constant effort. The priority system can be managed by a small group of key employees in a small organization. Or in larger organizations, the priority system can be managed by the project office or a governance team of senior managers.

Senior Management Input

Management of a portfolio system requires two major inputs from senior management. First, senior management must provide guidance in establishing selection criteria that strongly align with the current organization strategies. Second, senior management must annually decide how they wish to balance the available organizational resources (people and capital) among the different types of projects. A preliminary decision of balance must be made by top management (e.g., 20 percent compliance, 50 percent strategic, and 30 percent operational) before project selection takes place, although the balance may be changed when the projects submitted are reviewed. Given these inputs the priority team or project office can carry out its many responsibilities, which include supporting project sponsors and representing the interests of the total organization.

Governance Team Responsibilities

The governance team, or project office, is responsible for publishing the priority of every project and ensuring the process is open and free of power politics. For example, most organizations using a governance team or project office use an electronic bulletin board to disperse the current portfolio of projects, the current status of each project, and current issues. This open communication discourages power plays. Over time the governance team evaluates the progress of the projects in the portfolio. If this whole process is managed well, it can have a profound impact on the success of an organization. See Snapshot from Practice 2.3: Project Code Names for the rationale behind titles given to projects.

Constant scanning of the external environment to determine if organizational focus and/or selection criteria need to be changed is imperative. Periodic priority review and changes need to keep current with the changing environment and keep a unified vision of organization focus. If projects are classified by must do, operation, and strategic, each project in its class should be evaluated by the same criteria. Enforcing the project priority system is critical. Keeping the whole system open and aboveboard is important to maintaining the integrity of the system and keeping new, young executives from going around the system.

Balancing the Portfolio for Risks and Types of Projects

A major responsibility of the priority team is to balance projects by type, risk, and resource demand. This requires a total organization perspective. Hence, a proposed page 53project that ranks high on most criteria may not be selected because the organization portfolio already includes too many projects with the same characteristics—for example, project risk level, use of key resources, high cost, non-revenue-producing, and long durations. Balancing the portfolio of projects is as important as selecting projects. Organizations need to evaluate each new project in terms of what it adds to the project mix. Short-term needs must be balanced with long-term potential. Resource usage needs to be optimized across all projects, not just the most important project.

Two types of risk are associated with projects. First are risks associated with the total portfolio of projects, which should reflect the organization’s risk profile. Second are specific project risks that can inhibit the execution of a project. In this chapter we look only to balancing the organizational risks inherent in the project portfolio, such as market risk, ability to execute, time-to-market, and technology advances. Project-specific risks will be covered in detail in Chapter 7.

David and Jim Matheson studied R&D organizations and developed a classification scheme that could be used for assessing a project portfolio (see Figure 2.8).8 They separated projects in terms of degree of difficulty and commercial value and came up with four basic types of projects:

FIGURE 2.8

Project Portfolio Matrix

page 54

Bread-and-butter projects are relatively easy to accomplish and produce modest commercial value. They typically involve evolutionary improvements to current products and services. Examples include software upgrades and manufacturing cost-reduction efforts.

Pearls are low-risk development projects with high commercial payoffs. They represent revolutionary commercial advances using proven technology. Examples include next-generation integrated circuit chips and subsurface imaging to locate oil and gas.

Oysters are high-risk, high-value projects. These projects involve technological breakthroughs with tremendous commercial potential. Examples include embryonic DNA treatments and new kinds of metal alloys.

White elephants are projects that at one time showed promise but are no longer viable. Examples include products for a saturated market and a potent energy source with toxic side effects.

The Mathesons report that organizations often have too many white elephants and too few pearls and oysters. To maintain strategic advantage they recommend that organizations capitalize on pearls, eliminate or reposition white elephants, and balance resources devoted to bread-and-butter and oyster projects to achieve alignment with overall strategy. Although their research centers on R&D organizations, their observations appear to hold true for all types of project organizations.

Summary

Multiple competing projects, limited skilled resources, dispersed virtual teams, time-to-market pressures, and limited capital serve as forces for the emergence of project portfolio management that provides the infrastructure for managing multiple projects and linking business strategy with project selection. The most important element of this system is the creation of a ranking system that utilizes multiple, weighted criteria that reflect the mission and strategy of the firm. It is critical to communicate priority criteria to all organizational stakeholders so that the criteria can be the source of inspiration for new project ideas.

page 55

Every significant project selected should be ranked and the results published. Senior management must take an active role in setting priorities and supporting the priority system. Going around the priority system will destroy its effectiveness. Project review boards need to include seasoned managers who are capable of asking tough questions and distinguishing facts from fiction. Resources (people, equipment, and capital) for major projects must be clearly allocated and not conflict with daily operations or become an overload task.

The governance team needs to scrutinize significant projects in terms of not only their strategic value but also their fit with the portfolio of projects currently being implemented. Highly ranked projects may be deferred or even turned down if they upset the current balance among risks, resources, and strategic initiatives. Project selection must be based not only on the merits of the specific project but also on what it contributes to the current project portfolio mix. This requires a holistic approach to aligning projects with organization strategy and resources.

Key Terms

Organization politics, 37

Review Questions

Describe the major components of the strategic management process.

Explain the role projects play in the strategic management process.

How are projects linked to the strategic plan?

The portfolio of projects is typically represented by compliance, strategic, and operations projects. What impact can this classification have on project selection?

Why does the priority system described in this chapter require that it be open and published? Does the process encourage bottom-up initiation of projects? Does it discourage some projects? Why?

Why should an organization not rely only on ROI to select projects?

Discuss the pros and cons of the checklist versus the weighted factor method of selecting projects.

SNAPSHOT  FROM PRACTICE

FROM PRACTICE

Discussion Questions

2.1 Does IBM’s Watson’s Jeopardy Project Represent a Change in Strategy?

Why would IBM want to move from computer hardware to service products?

What impact will artificial intelligence (AI) have on the field of project management?

2.2 Crisis IT

What benefits did Frontier Airlines obtain by using a weighted scoring scheme to assess the value of projects?

2.3 Project Code Names

Can you think of a project code name not mentioned in the Snapshot? What function did it serve?

page 56

Exercises

You manage a hotel resort located on the South Beach on the Island of Kauai in Hawaii. You are shifting the focus of your resort from a traditional fun-in-the-sun destination to eco-tourism. (Eco-tourism focuses on environmental awareness and education.) How would you classify the following projects in terms of compliance, strategic, and operational?

Convert the pool heating system from electrical to solar power.

Build a four-mile nature hiking trail.

Renovate the horse barn.

Launch a new promotional campaign with Hawaii Airlines.

Convert 12 adjacent acres into a wildlife preserve.

Update all the bathrooms in condos that are 10 years old or older.

Change hotel brochures to reflect eco-tourism image.

Test and revise disaster response plan based on new requirements.

How easy was it to classify these projects? What made some projects more difficult than others? What do you think you now know that would be useful for managing projects at the hotel?

Two new software projects are proposed to a young, start-up company.* The Alpha project will cost $150,000 to develop and is expected to have an annual net cash flow of $40,000. The Beta project will cost $200,000 to develop and is expected to have an annual net cash flow of $50,000. The company is very concerned about their cash flow. Using the payback period, which project is better from a cash flow standpoint? Why?

A five-year project has a projected net cash flow of $15,000, $25,000, $30,000, $20,000, and $15,000 in the next five years. It will cost $50,000 to implement the project. If the required rate of return is 20 percent, conduct a discounted cash flow calculation to determine the NPV.

You work for the 3T company, which expects to earn at least 18 percent on its investments. You have to choose between two similar projects. The following chart shows the cash information for each project. Which of the two projects would you fund if the decision were based only on financial information? Why?

You are the head of the project selection team at SIMSOX.* Your team is considering three different projects. Based on past history, SIMSOX expects at least a rate of return of 20 percent.

page 57

Given the following information for each project, which one should be SIMSOX’s first priority? Should SIMSOX fund any of the other projects? If so, what should be the order of priority based on return on investment?

Project: Dust Devils

| Year | Investment | Revenue Stream | ||

| 0 | $500,000 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 50,000 | |||

| 2 | 250,000 | |||

| 3 | 350,000 |

Project: Osprey

| Year | Investment | Revenue Stream | ||

| 0 | $250,000 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 75,000 | |||

| 2 | 75,000 | |||

| 3 | 75,000 | |||

| 4 | 50,000 |

Project: Voyagers

| Year | Investment | Revenue Stream | ||

| 0 | $75,000 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 15,000 | |||

| 2 | 25,000 | |||

| 3 | 50,000 | |||

| 4 | 50,000 | |||

| 5 | 150,000 |

You are the head of the project selection team at Broken Arrow Records. Your team is considering three different recording projects. Based on past history, Broken Arrow expects at least a rate of return of 20 percent.

Given the following information for each project, which one should be Broken Arrow’s first priority? Should Broken Arrow fund any of the other projects? If so, what should be the order of priority based on return on investment?

Recording Project: Time Fades Away

| Year | Investment | Revenue Stream | ||

| 0 | $600,000 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 600,000 | |||

| 2 | 75,000 | |||

| 3 | 20,000 | |||

| 4 | 15,000 | |||

| 5 | 10,000 |

page 58

Recording Project: On the Beach

| Year | Investment | Revenue Stream | ||

| 0 | $400,000 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 400,000 | |||

| 2 | 100,000 | |||

| 3 | 25,000 | |||

| 4 | 20,000 | |||

| 5 | 10,000 |

Recording Project: Tonight’s the Night

| Year | Investment | Revenue Stream | ||

| 0 | $200,000 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 200,000 | |||

| 2 | 125,000 | |||

| 3 | 75,000 | |||

| 4 | 20,000 | |||

| 5 | 10,000 |

The Custom Bike Company has set up a weighted scoring matrix for evaluation of potential projects. Following are five projects under consideration.

Using the scoring matrix in the following chart, which project would you rate highest? Lowest?

If the weight for “Strong Sponsor” is changed from 2.0 to 5.0, will the project selection change? What are the three highest-weighted project scores with this new weight?

Why is it important that the weights mirror critical strategic factors?

*The solution to these exercises can be found in Appendix One.

Project Screening Matrix

page 59

References

Adler, P. S., et al., “Getting the Most Out of Your Product Development Process,” Harvard Business Review, vol. 74, no. 2, 2003, pp. 134–52.

Benko, C., and F. W. McFarlan, Connecting the Dots: Aligning Projects with Objectives in Unpredictable Times (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003).

Boyer, C., “Make Profit Your Priority,” PM Network, October 2003, pp. 37–42.

Brown, K., N. Hyer, and R. Ettenson, “The Question Every Project Team Should Answer,” Sloan Management Review, vol. 55, no. 1 (2013), pp. 49–57.

Cohen, D., and R. Graham, The Project Manager’s MBA (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001), pp. 58–59.

Descamps, J. P., “Mastering the Dance of Change: Innovation as a Way of Life,” Prism, Second Quarter, 1999, pp. 61–67.

Doran, G. T., “There’s a Smart Way to Write Management Goals and Objectives”, Management Review, November 1981, pp. 35–36.

Floyd, S. W., and B. Woolridge, “Managing Strategic Consensus: The Foundation of Effectiveness Implementation,” Academy of Management Executives, vol. 6, no. 4 (1992), pp. 27–39.

Foti, R., “Louder Than Words,” PM Network, December 2002, pp. 22–29.

Foti, R., “Make Your Case, Not All Projects Are Equal,” PM Network, July 2003, pp. 35–43.

Friedman, Thomas L., Hot, Flat, and Crowded (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2008).

Helm, J., and K. Remington, “Effective Project Sponsorship: An Evaluation of the Executive Sponsor in Complex Infrastructure Projects by Senior Project Managers,” Project Management Journal, vol. 36, no. 1 (September 2005), pp. 51–61.

Hutchens, G., “Doing the Numbers,” PM Network, March 2002, p. 20.

“IBM Wants to Put Watson in Your Pocket,” Bloomberg Businessweek, September 17–23, 2012, pp. 41–42.

Johnson, R. E., “Scrap Capital Project Evaluations,” Chief Financial Officer, May 1998, p. 14.

Kaplan, R. S., and D. P. Norton, “The Balanced Scorecard—Measures That Drive Performance,” Harvard Business Review, January/February 1992, pp. 73–79.

Kenny, J., “Effective Project Management for Strategic Innovation and Change in an Organizational Context,” Project Management Journal, vol. 34, no. 1 (2003), pp. 45–53.

Kharbanda, O. P., and J. K. Pinto, What Made Gertie Gallop: Learning from Project Failures (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996), pp. 106–11, 263–83.

Korte, R. F., and T. J. Chermack, “Changing Organizational Culture with Scenario Planning,” Futures, vol. 39, no. 6 (August 2007), pp. 645–56.

Leifer, R., C. M. McDermott, G. C. O’Connor, L. S. Peters, M. Price, and R. W. Veryzer, Radical Innovation: How Mature Companies Can Outsmart Upstarts (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

page 60

Magretta, Joan, Understanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competition and Strategy (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2011).

Milosevic, D. Z., and S. Srivannaboon, “A Theoretical Framework for Aligning Project Management with Business Strategy,” Project Management Journal, vol. 37, no. 3 (August 2006), pp. 98–110.

Morris, P. W., and A. Jamieson, “Moving from Corporate Strategy to Project Strategy,” Project Management Journal, vol. 36, no. 4 (December 2005), pp. 5–18.

Mortensen, M., and H. K. Gardner, “The Overcommitted Organization,” Harvard Business Review, September/October 2017, pp. 58–65.

Motta, Silva, and Rogério Hermida Quintella, “Assessment of Non-Financial Criteria in the Selection of Investment Projects for Seed Capital Funding: The Contribution of Scientometrics and Patentometrics,” Journal of Technology Management Innovation, vol. 7, no. 3 (2012).

Raskin, P., et al., Great Transitions: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead, www.gtinitiative.org/documents/Great_Transitions.pdf. Accessed 6/3/08.

Schwartz, Peter, and Doug Randall, “An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and its Implications for United States National Security,” Global Business Network, Inc., October 2003.

Shenhar, A., “Strategic Project Leadership: Focusing Your Project on Business Success,” Proceedings of the Project Management Institute Annual Seminars & Symposium, San Antonio, Texas, October 3–10, 2002, CD.

Swanson, S., “All Things Considered,” PM Network, February 2011, pp. 36–40.

Case 2.1

Hector Gaming Company

Hector Gaming Company (HGC) is an educational gaming company specializing in young children’s educational games. HGC has just completed their fourth year of operation. This year was a banner year for HGC. The company received a large influx of capital for growth by issuing stock privately through an investment banking firm. It appears the return on investment for this past year will be just over 25 percent with zero debt! The growth rate for the last two years has been approximately 80 percent each year. Parents and grandparents of young children have been buying HGC’s products almost as fast as they are developed. Every member of the 56-person firm is enthusiastic and looking forward to helping the firm grow to be the largest and best educational gaming company in the world. The founder of the firm, Sally Peters, has been written up in Young Entrepreneurs as “the young entrepreneur to watch.” She has been able to develop an organizational culture in which all stakeholders are committed to innovation, continuous improvement, and organization learning.

Last year, 10 top managers of HGC worked with McKinley Consulting to develop the organization’s strategic plan. This year the same 10 managers had a retreat in Aruba to formulate next year’s strategic plan using the same process suggested by McKinley Consulting. Most executives seem to have a consensus of where the firm should go page 61in the intermediate and long term. But there is little consensus on how this should be accomplished. Peters, now president of HGC, feels she may be losing control. The frequency of conflicts seems to be increasing. Some individuals are always requested for any new project created. When resource conflicts occur among projects, each project manager believes his or her project is most important. More projects are not meeting deadlines and are coming in over budget. Yesterday’s management meeting revealed some top HGC talent have been working on an international business game for college students. This project does not fit the organization vision or market niche. At times it seems everyone is marching to his or her own drummer. Somehow more focus is needed to ensure everyone agrees on how strategy should be implemented, given the resources available to the organization.

Yesterday’s meeting alarmed Peters. These emerging problems are coming at a bad time. Next week HGC is ramping up the size of the organization, number of new products per year, and marketing efforts. Fifteen new people will join HGC next month. Peters is concerned that policies be in place that will ensure the new people are used most productively. An additional potential problem looms on the horizon. Other gaming companies have noticed the success HGC is having in their niche market; one company tried to hire a key product development employee away from HGC. Peters wants HGC to be ready to meet any potential competition head on and to discourage any new entries into their market. Peters knows HGC is project driven; however, she is not as confident that she has a good handle on how such an organization should be managed—especially with such a fast growth rate and potential competition closer to becoming a reality. The magnitude of emerging problems demands quick attention and resolution.

Peters has hired you as a consultant. She has suggested the following format for your consulting contract. You are free to use another format if it will improve the effectiveness of the consulting engagement.

What is our major problem?

Identify some symptoms of the problem.

What is the major cause of the problem?

Provide a detailed action plan that attacks the problem. Be specific and provide examples that relate to HGC.

Case 2.2

Film Prioritization

The purpose of this case is to give you experience in using a project priority system that ranks proposed projects by their contribution to the organization’s objectives and strategic plan.

COMPANY PROFILE

The company is the film division for a large entertainment conglomerate. The main office is located in Anaheim, California. In addition to the feature film division, the conglomerate includes theme parks, home videos, a television channel, interactive games, and theatrical productions. The company has been enjoying steady growth over the past 10 years. Last year total revenues increased by 12 percent to $21.2 billion. The company is engaged in negotiations to expand its theme park empire to mainland China and Poland. The film division generated $274 million in revenues, which was an page 62increase of 7 percent over the past year. Profit margin was down 3 percent to 16 percent because of the poor response to three of the five major film releases for the year.

COMPANY MISSION

The mission for the firm is as follows:

Our overriding objective is to create shareholder value by continuing to be the world’s premier entertainment company from a creative, strategic, and financial standpoint.

The film division supports this mission by producing four to six high-quality, family entertainment films for mass distribution each year. In recent years the CEO of the company has advocated that the firm take a leadership position in championing environmental concerns.

COMPANY “MUST” OBJECTIVES

Every project must meet the must objectives as determined by executive management. It is important that selected film projects not violate such objectives of high strategic priority. There are three must objectives:

All projects meet current legal, safety, and environmental standards.

All film projects should receive a PG or lower advisory rating.

All projects should not have an adverse effect on current or planned operations within the larger company.

COMPANY “WANT” OBJECTIVES

Want objectives are assigned weights for their relative importance. Top management is responsible for formulating, ranking, and weighting objectives to ensure that projects support the company’s strategy and mission. The following is a list of the company’s want objectives:

Be nominated for and win an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature or Best Picture of the Year.

Generate additional merchandise revenue (action figures, dolls, interactive games, music CDs).

Raise public consciousness about environmental issues and concerns.

Generate profit in excess of 18 percent.

Advance the state of the art in film animation and preserve the firm’s reputation.

Provide the basis for the development of a new ride at a company-owned theme park.

ASSIGNMENT

You are a member of the priority team in charge of evaluating and selecting film proposals. Use the provided evaluation form to formally evaluate and rank each proposal. Be prepared to report your rankings and justify your decisions.

Assume that all of the projects have passed the estimated hurdle rate of 14 percent ROI. In addition to the brief film synopsis, the proposals include the following financial projections of theater and video sales: 80 percent chance of ROI, 50 percent chance of ROI, and 20 percent chance of ROI.

For example, for proposal #1 (Dalai Lama) there is an 80 percent chance that it will earn at least 8 percent return on investment (ROI), a 50/50 chance the ROI will be 18 percent, and a 20 percent chance that the ROI will be 24 percent.

page 63

FILM PROPOSALS

PROJECT PROPOSAL 1: MY LIFE WITH DALAI LAMA

This project is an animated, biographical account of the Dalai Lama’s childhood in Tibet based on the popular children’s book Tales from Nepal. The Lama’s life is told through the eyes of “Guoda,” a field snake, and other local animals who befriend the Dalai Lama and help him understand the principles of Buddhism.

| Probability | 80% | 50% | 20% | |||

| ROI | 8% | 18% | 24% |

PROJECT PROPOSAL 2: HEIDI

The project is a remake of the classic children’s story with music written by award-winning composers Syskle and Obert. The big-budget film will feature top-name stars and breathtaking scenery of the Swiss Alps.

| Probability | 80% | 50% | 20% | |||

| ROI | 2% | 2% | 30% |

PROJECT PROPOSAL 3: THE YEAR OF THE ECHO

This project is a low-budget documentary that celebrates the career of one of the most influential bands in rock-and-roll history. The film will be directed by new-wave director Elliot Cznerzy and will combine concert footage and behind-the-scenes interviews spanning the 25-year history of the rock band the Echos. In addition to great music, the film will focus on the death of one of the founding members from a heroin overdose and reveal the underworld of sex, lies, and drugs in the music industry.

| Probability | 80% | 50% | 20% | |||

| ROI | 12% | 14% | 18% |

PROJECT PROPOSAL 4: ESCAPE FROM RIO JAPUNI

This project is an animated feature set in the Amazon rainforest. The story centers around Pablo, a young jaguar that attempts to convince warring jungle animals that they must unite and escape the devastation of local clear cutting.

| Probability | 80% | 50% | 20% | |||

| ROI | 15% | 20% | 24% |

PROJECT PROPOSAL 5: NADIA!

This project is the story of Nadia Comaneci, the famous Romanian gymnast who won three gold medals at the 1976 Summer Olympic Games. The low-budget film will document her life as a small child in Romania and how she was chosen by Romanian authorities to join their elite, state-run athletic program. The film will highlight how Nadia maintained her independent spirit and love for gymnastics despite a harsh, regimented training program.

| Probability | 80% | 50% | 20% | |||

| ROI | 8% | 15% | 20% |

page 64

Project Priority Evaluation Form

PROJECT PROPOSAL 6: KEIKO—ONE WHALE OF A STORY