CHAPTER 2

Sweat the Right Stuff

Everybody talks about the weather,

but nobody does anything about it.

—Mark Twain

What are the most effective steps each of us can take to reduce our carbon emissions? This is the question the Climate Team at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) set out to answer in this book. Of course, the best steps for you depend to some extent on how you live now. Some of us drive big cars, others ride the bus; some live in large houses, others in tiny studio apartments. The United States is a big country, and geography makes a difference, too: in colder climates, home heating naturally accounts for a far greater share of a household's emissions; city dwellers, meanwhile, tend to be less reliant on cars, with far fewer emissions in the transportation category than their rural counterparts.

While there is no single, one-size-fits-all solution to reducing carbon emissions, the first step is to look closely at your emissions and set a goal to reduce them. Whatever your current circumstances, we suggest that you aim to reduce your carbon emissions by 20 percent over the coming year.

Of course, you may find that you can make even deeper cuts. If so, great, because ultimately much deeper cuts in overall carbon emissions will be needed to dramatically slow the pace of climate change. But 20 percent is a meaningful—and achievable—goal to start with. It's large enough that, if adopted by enough Americans, it can make a significant difference to global warming. If all Americans reduced their emissions by 20 percent, the total of heat-trapping carbon dioxide entering the atmosphere each year would drop by well over 1 billion tons. That's as much carbon dioxide as 200 of the nation's average-sized coal-fired plants produce annually, or about half of the total U.S. carbon emissions from coal.

To avoid some of the most harmful consequences of global warming, a consensus has emerged among climate scientists that the world's nations must lower their emissions by 80 percent or more by the middle of this century, a goal that could be achieved by reducing global emissions by roughly 3 percent annually. Consider your personal commitment to reduce emissions by 20 percent as a down payment to help give the nation a healthy start along this path.

A big consideration for our team in adopting the 20 percent goal is that most Americans can achieve this. Toward that end, we offer a range of suggestions in this book—including many low-cost and no-cost solutions.

As we saw in chapter 1, the average American's activities are responsible for some 21 tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually. To lower that by 20 percent, you will need to find roughly 4 tons’ worth of reductions. Of course, your personal contribution to global warming may vary significantly from this average figure. People who live in large houses, eat a lot of beef, or travel regularly may have considerably higher emissions than the national average, for instance. It will take a bit of effort to find the changes that best fit your lifestyle. But we are confident that by following the practical advice in this book, each of us can avoid emitting some 20 percent of the heat-trapping carbon dioxide we are each currently responsible for creating.

In our recommendations for steps you can take to reduce your carbon emissions, our team of authors has adopted a systematic approach. While many books and websites offer tips for lowering one's carbon footprint, we found that many of these tips have only a tiny payoff. In our quick review, we found recommendations ranging from staying out of elevators to starting worm farms in your basement and drinking locally brewed beer. None of those suggestions is likely to do any harm, but none of them will significantly reduce your carbon emissions.

To determine the most effective individual actions to combat global warming, we analyzed the climate impacts of hundreds of potential consumer decisions, from insulating your home to changing your diet. Our team used an input-output model that links detailed economic data about U.S. consumer spending in over 500 sectors with data on global warming emissions broken down by industry. By painstakingly allocating these emissions into the model's detailed consumption categories, we were ultimately able to derive both the direct and indirect emissions that resulted from every dollar spent by U.S. consumers. (For much more on the modeling methodology, see appendix C.)

UCS Climate Team Recommendation

Whatever your current circumstances, we suggest that you aim to reduce your carbon emissions by 20 percent over the coming year—a meaningful and achievable goal.

This approach grew out of a pathbreaking earlier project. In the late 1990s, the Union of Concerned Scientists published The Consumer's Guide to Effective Environmental Choices. That book evaluated the environmental impacts of a variety of consumer activities and daily decisions. It pointed out that just a handful of consumer choices accounted for the bulk of an average person's environmental impact. It advised consumers not to worry about many inconsequential decisions that received a disproportionate amount of media attention: whether to choose paper or plastic at the grocery store, whether to diaper your baby in cloth or disposables. What turned out to be more effective from a practical standpoint was to focus on a handful of common purchases and behaviors. In other words, that book argued, “stop sweating the small stuff” and focus on the decisions that have the greatest impact.

As the following chapters will show in detail, much the same advice holds for global warming. Whenever possible, we feature choices that provide the greatest payoffs. We also present some smaller-scale suggestions whose ease and practicality make them worthwhile.

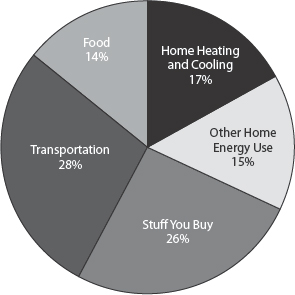

To start, take a look at the pie chart on the next page. Because it is based on average emissions, it may vary substantially from your personal numbers. Nevertheless, it's useful for thinking about the problem.

The first thing to notice is that the biggest share of Americans’ emissions comes from transportation. For this reason, we begin our analysis with this sector, which is overwhelmingly dominated by the emissions from driving our cars. As explained in chapter 4, many of us could achieve most or all of our first-year 20 percent reduction in carbon emissions simply by trading in our current car for a more energy-efficient model. In fact, switching from an average vehicle getting about 20 miles per gallon (mpg) to one getting 40 mpg would, in one fell swoop, reduce your emissions by nearly the four tons annually needed to meet the goal. No matter when you plan to purchase your next car, it will surely be one of the most important decisions you make in terms of your overall impact on global warming.

Figure 2.1. Where the Average American's Carbon Emissions Come From

The breakdown in sources of carbon emissions for

the average American shows that transportation is

the largest single category. Source: UCS modeling.

As the chart also shows, the two sectors that make up household energy usage—heating and cooling, plus lighting and the electricity for appliances and home electronics—account for about one-third of our average emissions. This is another area with great potential for reducing carbon emissions. Installing and using a programmable thermostat, if you haven't done so already, can reduce home-heating costs—and heating-related emissions—by about 15 percent, for a savings of more than a half ton of emissions annually on average. Dollar for dollar, this may be one of the most effective single actions you can take. You can probably find other good ways to drive down heat-trapping emissions without remodeling your home. However, if you are able to remodel, the possibilities are far greater.

Take the experience of Ann Luskey, a mother of three in Bethesda, Maryland. Luskey wanted to reduce her environmental impact, so she moved from an enormous suburban home to one less than half its size. But she wanted to do even more. So, working with a local contractor, she invested in retrofitting a “zero-net-energy” home—one that produces as much energy as it consumes. Zero-net-energy homes are beginning to spring up around the country. Luskey's is built with ultratight insulation and an array of solar panels on the roof. It required a significant investment of time, but the total price, including the retrofits, was not substantially higher than that of other homes in her new neighborhood. And now, after her initial outlay, Luskey has no monthly utility bills to pay. She says she prefers her new home's smaller, well-designed spaces and loves that it's close to schools and recreational spaces where her children can ride their bikes. Most of all, though, Luskey says that her experience with “green building” made her realize that energy-smart choices “really don't have to involve sacrifice.”

As we each search for the reductions that best fit our personal circumstances, it is helpful to remember Luskey's insight. Despite some stories in the press, reducing our carbon footprint doesn't mean that we have to go to extremes. A recent article in the New York Times described the lengths to which a family in upstate New York had gone to achieve a green lifestyle. They had unplugged their refrigerator, turned their home's thermostat to a frosty 52 degrees in winter, and didn't allow one son to play on a Little League baseball team because of the emissions the extra driving would cause. This example gives a false impression. In fact, we don't have to shiver in our homes or read by candlelight to make serious reductions in our carbon emissions. Instead, we each just need to make smarter use of energy resources.

Step 1: Look Closely at Your Current Energy Usage

When we begin to look at Americans’ energy usage, it is amazing to see how much energy we waste on average. Considering that we know how to make energy-efficient homes and manufacture cars that burn a fraction of the fuel that most current gas-guzzlers consume, and with the costs of energy already high and very likely to go higher, it is hard to understand why most Americans don't already make more energy-efficient choices.

Part of the answer is that many of our energy expenditures are relatively invisible to us. Most people simply aren't aware of how energy inefficient many of their choices are. Sure, we see the dollars mounting in a speedy blur when we fill the tank at a gas station. But when we turn up the thermostat or switch on the lights, most of us have very little sense of the consequences of those actions in terms of energy usage or excess carbon emissions.

Try this thought experiment: do you know where your home's electricity comes from? Do you know which of your appliances use the most energy? Or where your home's biggest heat losses are?

If your answer to any these questions is no, you are certainly not alone. A 2010 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences highlighted how inaccurate public perceptions tend to be on the subject of energy usage. More than 500 people from across the United States were asked a series of questions about what they thought were the most effective strategies for conserving energy. They were asked to estimate how much energy was used in various routine household activities and how much they thought they might save if they made certain changes. The respondents not only underestimated how much energy they could save; their estimates were also, on average, nearly three times lower than the actual savings they could achieve.

As the researchers analyzed the results, they noticed that the inaccuracies followed a pattern: people tended to favor turning off appliances and lights (what the researchers call “curtailment” efforts) over making improvements in efficiency. For instance, people were five times more likely to choose turning off lights as a strategy for saving energy than switching to more energy-efficient lightbulbs, even though replacing old-fashioned incandescent bulbs can often result in savings of 75 percent or more in electricity costs. Of course, turning off lights when they are not in use is a great way to save energy, but think about that for a moment: you would have to turn off your lights entirely for three out of every four days to achieve comparable savings. The point is: people tend to underestimate how powerful it can be to use energy more efficiently.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

In a 2010 study, Americans dramatically underestimated how much energy they might save by implementing a variety of energy efficiency measures at home. Their estimates were, on average, nearly three times lower than the actual savings they could achieve.

Along the same lines, the study found that people were twice as likely to favor curtailing their use of appliances rather than using more energy-efficient ones. In open-ended questions, only 12 percent of the respondents even mentioned efficiency improvements. The fact is, making changes to improve efficiency often yields far greater savings in energy and emissions than trying to curtail or do without.

As the study's authors note, their results show that all too often people “believe they are doing their part to reduce energy use when they engage in low-effort, low-impact actions instead of focusing on changes that would make a bigger difference.” In the chapters ahead, we will tackle many of these issues to help avoid this pitfall. By improving our “energy literacy,” each of us can understand more precisely where our personal emissions are coming from.

The first step is to review your energy usage. Save and review your gas receipts and calculate your fuel economy. Look closely at your home's utility bills. Some utility companies now provide information showing how your energy usage stacks up against that of your neighbors. And many websites can help you calculate your carbon footprint. One well-respected example is a carbon calculator developed in conjunction with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, available at http://coolclimate.berkeley.edu/uscalc. Websites such as this one ask visitors to enter specific information about their energy usage, such as how many miles they drive annually and what kind of home they live in. On the basis of the data provided, the websites offer an estimate of the amount of carbon an individual or household emits.

Carbon calculators are valuable tools, but estimating your total carbon emissions is only one piece of the picture. It is also important to find out where the biggest energy hogs in your home and your lifestyle are hiding. Before you buy a major appliance, read the labels and specification sheets to learn how much energy it consumes. Invest $20 in an appliance electricity meter that you can use to see which of your appliances are energy hogs. A wealth of this kind of information can be found through the federal government, for instance, at www.energysavers.gov, a website run by the U.S. Department of Energy. Review your travel patterns, and think about how you handle home activities such as lawn care. You might be surprised at what you find when you consider energy usage and emissions related to the many choices in your life.

As you learn more about the sources of your personal contribution to carbon emissions, you will most likely find yourself thinking differently about some of your choices. The fact is, when people realize they're being wasteful, most want to make some changes in the way they do things.

A 2002 psychological study demonstrated how information about energy usage can affect consumer behavior. In the study, 100 participants were shown an ultramodern washing machine and told they would be helping the engineers design a next-generation control panel. Using a simulated computer control panel, the participants made choices about 20 consecutive loads of laundry. All the control panels were the same—with one exception: some included a simple “real-time” meter purporting to show the amount of electricity the washing machine was using at different settings. At the end of the experiment, the people with the real-time energy usage information were found to have voluntarily set their washing machines to settings that used some 21 percent less power than their counterparts’ settings. In other words, even though the participants wouldn't derive any personal savings from their choices, simply having information about the electricity the machine would use inclined them to use it wisely.

As you begin to think about your energy usage, don't forget to consider transportation and purchasing choices and even your diet. As we discuss in later chapters of this book, when each of us becomes more aware of the emissions that result from all the various choices we make, we are far more likely to discover ways in all these arenas to lower our carbon footprints.

Step 2: Make a Plan

Once you have learned where your personal carbon emissions are coming from, you can better decide which areas of your life offer the best reductions. Part II of this book will help you make these choices.

Chapter 4 looks at the average American consumer's global warming emissions from transportation, mainly from our cars. This chapter can help you make transportation choices that will get you where you want to go while driving down your share of these carbon emissions.

Chapter 5 addresses household heating and cooling, which accounts for a significant share of the nation's carbon dioxide emissions and, depending upon where you live, up to half of your total emissions at home. Making thoughtful choices about heating and cooling can greatly reduce your emissions while still allowing you to live comfortably and save money on your energy bills. In this chapter, we explain which changes will make the most difference in reducing your carbon emissions. And we review some of the latest advances in green building technology as well as the ins and outs of purchasing electricity from renewable energy sources.

Next to home heating and cooling, the biggest sources of residential carbon emissions are lighting, laundry and kitchen appliances, and the rapidly growing category of consumer electronics: televisions, computers, and other electronic devices. Chapter 6 explores the most effective strategies for lowering the emissions from each of these sources. It discusses ways to monitor your home's electricity usage and answers such questions as whether it is better to use a microwave or a conventional oven, when to replace your refrigerator, and what to look for in a new one.

In chapter 7 we tease apart the climate consequences of our food choices by tracking the heat-trapping emissions from farms, the industries that supply farmers with chemicals and equipment, and the long chain of processing, transportation, and distribution stretching from farm to table. Not all foods have the same global warming impact: this chapter discusses the outsized impact of meat consumption, emissions related to bottled water and other beverages, and the extent to which eating locally produced food reduces your global warming emissions.

Finally, chapter 8 focuses on the emissions caused by the stuff we buy: the clothing, furnishings, toys, books—everything we accumulate and often throw out much too soon—which accounts for roughly 10 percent of our personal carbon emissions. This chapter also reviews the services we buy, from health care through legal assistance, insurance, visits to hotels, movie theaters, and even the car wash, which together account for another 16 percent. Here you will find plenty of information about the climate consequences of the purchasing decisions you make every day.

Step 3: Look Around and Connect

By following the advice in part II, you will figure out the best changes you can make to reduce your emissions by 20 percent (or perhaps even more) this year.

While individual actions matter, they aren't sufficient. As individual consumers, we simply don't have control of all the decisions that must be made in tackling global warming. While we can take responsibility for our part of the problem, we also need to call on elected officials and corporate leaders to create better policies to reduce emissions. People like you, who have taken action in your own lives, have a vital role to play. The smart personal choices you have made will help you be a leader in your community and in your workplace or school, demonstrating how feasible and beneficial change can be.

Part III shows you how to step up, connect with others, and share the knowledge and experience you've gained. Family and friends are the best place to start, and chapter 9 shows you how. Chapter 10 explains how to apply what you've learned in your workplace. This chapter documents some of the most promising changes now underway in a variety of workplaces, from small firms to large companies, as well as at colleges, churches, and municipal facilities.

Chapter 11 shows how to make your voice heard beyond your local community. From our cities and towns to our state governments, officials make many decisions about how our tax dollars are spent. The taxes we pay can be used to continue on our current, recklessly unsustainable path of energy usage—or they can be used to improve our energy future. Many of the most important planning decisions about transportation and utilities are made at the state and local levels. Meanwhile, at the federal level, in Washington, DC, a wide variety of consequential policy decisions are made and, there, lobbyists for the fossil fuel industry are pushing hard for continued support of policies that perpetuate our dependence on coal and oil, block renewable energy, and delay energy efficiency measures. This chapter highlights a number of successful local, state, and federal programs and offers ideas about how to get involved.

Finally, chapter 12 presents a vision of the low-carbon future that you can help create. This is no high-tech sci-fi scenario. Our neighborhoods will look and feel much the same as they do now. But you'll see solar panels on many rooftops, and wind turbines will dot the countryside, generating plenty of electricity. Our homes will look much the same, too, just retrofitted for much greater energy efficiency. And our home appliances, along with whatever new gizmos have come along, will do the same jobs they do today, using far less energy. Cars will run much more efficiently and will fill up on biofuels, electricity, or hydrogen, while cities will boast more and better mass transit. And a robust mix of residential and commercial development, combined with a network of high-speed railways, will reduce our dependence on cars.

The good news is that we already have many of the tools and technologies we need to lower our carbon emissions. We just need to get moving in the right direction. The imminent threat of global warming means we need to act fast. But across the country and around the world, a sea change has begun in the way many people think about their carbon emissions. International agreements and many U.S. federal policies have lagged, but all around us positive signs abound—proverbial green shoots.

These changes are visible when we begin to look for them. A recent report found that in the northeastern United States, some 60 percent of all planned new electricity-generating projects for the region—about 17,000 megawatts of capacity—involve renewable energy, including solar and wind power. That's the equivalent capacity of more than two dozen average-sized coal-fired plants.

Green building projects are fast becoming the norm. In Washington, DC, for example, the city planning department reports that all of the 200 large buildings planned or under construction have been designed to meet aggressive new energy efficiency standards. Meanwhile, scores of major companies are starting to reduce their carbon footprints. In just one example, Walmart recently pledged to make 22 million tons’ worth of reductions in its global warming emissions by 2015. That's the equivalent of taking nearly 4 million cars off the road.

The U.S. military, a huge energy consumer, is beginning to address the issue too: in 2010, U.S. Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus set the ambitious goal of deriving half of all the power used by the U.S. Navy and Marines from renewable energy sources by 2020—a figure Mabus says will include energy for bases as well as the fuel used for vehicles and ships. Among other benefits, the military considers its energy plan as a way to save lives. A 2007 report found that one U.S. military person is killed or wounded for every 24 military fuel convoys run in Afghanistan.

The fuel economy of new cars is also finally starting to change. Fuel economy was stuck at about 25 miles per gallon for decades, but it has been rising very slowly since 2005. Starting in 2012, progress kicked into high gear as new fuel efficiency standards and the first-ever national greenhouse gas standards for cars began to push new vehicles to significantly increase fuel economy and cut carbon emissions.

Taken together, these kinds of efforts are already adding up on a global scale. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2008 was a watershed year globally for investment in renewable sources of energy such as wind and solar power. For the first time ever, “green energy” investments exceeded total investments in coal, oil, and carbon-based energy, constituting some 56 percent of all money invested in the energy sector. Including businesses focused on energy efficiency and building retrofits, the total climate-related business sector had global revenues in 2008 even larger than those of the aerospace and defense industries, according to a report by HSBC Global Research, one of the world's largest financial institutions.

These important glimmers of hope indicate that once we get going, we can make changes happen quickly. That's good, because we need to act fast. For those with any doubts or questions about the pace and scope of global warming, chapter 3 provides a quick grounding in the science behind climate change that can help you spot and address some of the most egregious misrepresentations of the scientific evidence, which unfortunately have proliferated in the media and in our often polarized political discourse.

Reducing our global warming emissions is easier than you may think. A low-carbon future is within our reach, but only if all of us take steps toward it in our own lives and push for changes in the world around us. Though the task may sound huge, the transformation we need begins with each one of us, starting now.