![]()

The orchids display a remarkably diverse range of intriguing and beautiful pollination mechanisms, and include some of the most extraordinary examples of adaptation to insect visitors. Although earlier botanists had described the structure of orchid flowers and observed visits by insects, the nature and variations in detail of pollination mechanisms in orchids were first fully appreciated by Charles Darwin. His book The various contrivances by which Orchids are fertilised by Insects, first published in 1862, is the record of a great deal of painstaking and perceptive observation. From 1842 until his death 40 years later, Darwin lived at Down, close to the crest of the North Downs in Kent. Many of the British orchids are plants of chalky soils, and it was in the country around Down that many of Darwin’s observations were made. These were the orchids with which he was most familiar. They show well the essential features of pollination in the family, even though they embrace only a fraction of the variation found in other parts of the world, of which many examples are included in his book.

The orchids are, by common consent, one of the most advanced families of flowering plants – in the sense that the structure of their flowers has diverged more than almost any others from the condition of their primitive ancestors of 100 million years ago. They are the ultimate expression of the evolutionary trend of increasingly precise adaptation to particular flower-visiting insects seen in the zygomorphic flowers, considered in Chapter 6. But a very high degree of evolutionary advancement could equally be argued for the Composites (Asteraceae) (Chapter 6) and the grasses (Poaceae) (Chapter 9), which have quite different pollination mechanisms and relationships. It was suggested at the end of Chapter 6 that the very precise adaptations in orchids have evolved to provide specific and effective pollination of flowers which are often widely scattered and typically form only a small part of the bulk of the vegetation in which they grow. Many of the pollination systems that have evolved in this situation are in varying degrees pollinator-limited, which may make adaptive shifts to new pollination systems rather easy. The present chapter may be read with these thoughts in mind.

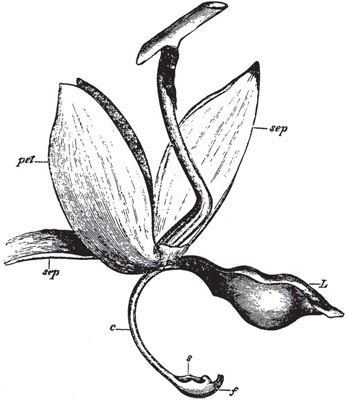

At first sight, an orchid flower has little in common with the flowers of any other family. However, when it is examined in detail it appears that it is, in effect, an exceedingly specialised version of the kind of flower seen in the lilies and their relatives (Liliaceae). A lily or tulip flower has six perianth segments, three outer and three inner, six stamens, again in two whorls of three, and an ovary made up of three fused carpels – though the ovary is superior in the tulip or lily, but inferior in the orchids. The orchid flower also has six perianth segments, though one segment of the inner whorl is usually larger than the others, and is called the lip (or labellum). The lip is strictly the uppermost petal, but in most orchids the ovary is twisted through 180° so that the flower is, in fact, upside down. The lip then appears at the bottom, where it forms an alighting platform for insects; it often has a spur or nectary at its base. It is in the stamens that the greatest modifications of the orchid flower are found. Most of the stamens have been either completely lost or reduced to sterile vestiges. Two members of the outer whorl are missing; Darwin believed that they had become fused with the sides of the lip, but it is generally thought now that they have vanished without trace. The remaining stamens, together with the stigmas, have become fused into a stout column which projects in the centre of the flower, above the lip. The small tropical Asian and Australian genus Neuwiedia (usually regarded as a primitive orchid, but sometimes, with the related two-stamened Apostasia, placed in a separate family Apostasiaceae) is a nicely illustrative ‘missing link’ with three fertile stamens (Dressler, 1993). In all other orchids, never more than two stamens are fertile, and in most orchids the only fertile stamen is the remaining one in the outer whorl. Only two stigmas are functional; the third forms the rostellum, which generally projects from the top of the column, and produces sticky matter whose function will be referred to repeatedly in what follows.

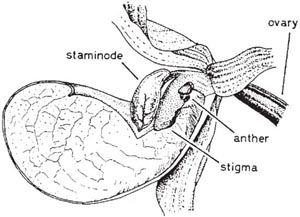

The orchids fall into two main groups. Most primitive are the Lady’s slipper orchids, Cypripedium and related genera (Fig. 7.1). In these, two stamens of the inner whorl are fertile, the third forming the front of the column. The single remaining stamen of the outer whorl is represented by a thick petal-like staminode, overarching the stigma. The lip forms a deep pouch. The flowers of the European Lady’s slipper Cypripedium calceolus (Fig. 7.2) offer no reward, but the bright yellow lip and somewhat fruity scent attract a variety of bees. In the colonies studied by Nilsson (1979a) on the Swedish island of Öland, the commonest visitors, and the most important for pollination, were medium-sized female solitary bees of the genus Andrena, especially A. haemorrhoa; in Czechoslovakia, Daumann (1968) found that the main pollinators were larger Andrena species such as A. tibialis and A. nigroaenea. The bees enter the lip through the obvious large opening. Large bees, such as bumblebees (and, on Öland, the larger Andrena species), seldom enter the flowers and if they do, they can generally quickly climb out the same way as they came in. Smaller bees are trapped in the lip. After some minutes of wing-buzzing and undirected efforts at escape, the bees begin to prise methodically under the stigma, slightly depressing the elastic lip. In so doing, they free a passage for themselves out through the back of the flower. From this point, the translucent ‘window-panes’ in the sides of the lip near its base probably help to guide the bee towards one of the two narrow openings on either side of the stigma and staminode, past one of the stamens where some of the sticky pollen is smeared onto the upper side of its thorax. On visiting another flower, the bee will leave pollen from the first flower on the stigma before it squeezes out past one of the two stamens to pick up a further load of pollen. The mechanism does not always work in this neat and tidy way; a bee may have to make several attempts before it finds its way out of the lip. However, it seems to be rare for a flower to receive its own pollen in the course of a single visit. The Lady’s slipper flower is generally an effective ‘one-way-traffic’ device, ensuring that the insect passes the stigma before it comes into contact with the anthers, which in a plant with few, large flowers should favour cross-pollination. This in itself is probably less effective than might be expected, because Cypripedium is rhizomatous and often grows in clonal patches. It has been suggested that after a few visits the bees learn to avoid the flowers; this would tend to limit pollinations within a single patch and the bees might then fly some distance before trying another Cypripedium flower. There seems to be no firm evidence on this question one way or the other.

Fig. 7.1 Lady’s slipper (Cypripedium calceolus). Flower with half of lip removed to show details of the column and the path taken by a visiting insect.

Fig. 7.2 Lady’s slipper (Cypripedium calceolus); close-up of lip to show the large opening by which a visiting insect enters the flower, the translucent ‘window-panes’ at the back of the lip, and one of the smaller openings beneath the anthers by which the insect escapes.

The bees visiting Cypripedium calceolus are predominantly females. This may be related to the scent of the flowers. The scent of the European Lady’s slipper is unusual in being dominated by octyl and decyl acetates, with smaller amounts of various other substances common in flower and fruit scents. These are chemically similar to constituents of pheromones important in odour-marking and other aspects of the behaviour of Andrena bees, suggesting that Cypripedium has evolved a scent which specifically manipulates the innate behavioural responses of its pollinators. Of two American forms of C. calceolus, var. parviflorum, pollinated by Ceratina bees (Anthophoridae), has a scent dominated by mono and sesquiterpenoids, and var. pubescens, pollinated by halictid bees, has a scent dominated by 1,3,5-trimethoxy benzene (Bergström et al., 1992).

The large genus Paphiopedilum is the tropical counterpart of the bee-pollinated Lady’s slippers. It has the same one-way pollination system, but the flowers are probably generally adapted to lure flies, beetles and perhaps other insects. The colours, prevailingly green, brown, dull red, purple and white in various combinations, the sometimes putrid smell, and other features of the flowers recall the deceptive fly-pollinated aroids and asclepiads (Chapter 10, see here). According to Atwood (1985) P. rothschildianum is pollinated by syrphid flies which are deceived into laying their eggs in the flowers, especially on the staminode (see here).

In the great majority of orchids there is only a single, much-modified anther. Like most anthers, this is two-lobed, but by contrast with the loose, powdery pollen of most plants, the pollen grains are bound together by slender elastic threads into pollen masses or pollinia. The two anthers which are fertile in Cypripedium are reduced to projections on the column, often forming part of the clinandrium – the little hood protecting the fertile anther. In the greater number of orchids, the anther is borne by a comparatively slender stalk on the back of the column. Its apex is close to the rostellum, and it is by their apices that the pollinia become attached to a visiting insect. This condition is found in the huge subfamily Epidendroideae, which grow in a wide diversity of habitats and include almost all the epiphytic orchids of the tropics as well as such temperate orchids as the helleborines (Epipactis, Cephalanthera) and twayblades (Listera), and also in the Lady’s tresses and related genera (subfamily Spiranthoideae). In the subfamily Orchidoideae, Orchis and its close relatives, the single anther is perched on top of the column, and the two pollinia are furnished with minute stalks or caudicles at their bases, attached to viscid discs (viscidia) formed of rostellum tissue, but in other members of the subfamily the relation of the pollinia to the viscid matter of the rostellum varies a good deal. The Orchidoideae are typically ground orchids, often grassland plants, and although a minority in the world orchid flora in both species and individuals, they are well represented in temperate regions and include many of the best-known orchid species of Europe and North America.

Fig. 7.3 Marsh helleborine (Epipactis palustris).

The marsh helleborine (Epipactis palustris) is a locally-distributed plant of open calcareous fens and dune slacks over much of Europe. The whitish flowers (Fig. 7.3 and Fig. 7.4), which have no noticeable scent, are borne in a loose raceme on a stem 10–30 cm or more tall, and are visited by a wide diversity of insects, including various bees, social and solitary wasps, ants and two-winged flies (Nilsson, 1978b). The summit of the column in a newly-opened flower is occupied by the large, projecting, almost globular rostellum, with the broad squarish stigma below it. The anther overhangs the rostellum. Even before the bud opens the anther cells dehisce, releasing the rather friable pollinia which come to lie with their tips touching the rostellum. As the rostellum matures, its outer surface develops into a soft elastic membrane; at a slight touch it becomes viscid, so that the pollinia stick to it. The tissue within the rostellum develops into a lining of sticky matter which, on exposure to air, hardens in a few minutes. An object brushing upwards and backwards against the rostellum easily removes the whole of the elastic skin of the rostellum as a little cap, which sticks firmly by its adhesive lining. The base of the lip forms a cup, the hypochile, containing nectar; its broad flat tip, the epichile, is attached to the base by a slender, elastic ‘waist’. An insect visiting the flower for nectar and alighting on the lip depresses it, and as long as it is feeding, is well clear of the rostellum and the pollinia. But as soon as it makes to leave the flower and takes its weight from the lip, the epichile returns to its original position. Darwin saw this as an important element in the mechanism of the flower, causing the visitor to fly upwards and strike the rostellum with its head as it left the flower, but Nilsson’s observations cast doubt on this, and Darwin himself expressed reservations in the second edition of his book. In the Isle of Wight, Darwin’s son, William, observed visits by honeybees, but he also saw visits (and pollinia removed) by small solitary wasps and by various Diptera. Honeybees are an introduced species in northern Europe, so they cannot be the original pollinators of E. palustris. Nilsson saw very few honeybees on marsh helleborines in Sweden. The flowers are probably primarily adapted to pollination by solitary wasps, perhaps particularly Eumenes, but a wide range of insects can bring about pollination, including honeybees if they are abundant. If the flowers are not visited by insects, the friable pollinia sooner or later break up, and the loose pollen falls down over the the rostellum and stigma. This may happen even before the flower opens, and the relative importance of cross and self-pollination probably varies greatly at different times and in different localities.

Fig. 7.4 Marsh helleborine (Epipactis palustris). Side view of flower with half of perianth removed.

The broad-leaved helleborine (Epipactis helleborine), another species very widespread in Europe (and naturalised in eastern North America), is a shade-loving plant perhaps more common along shady roadsides and wood margins than in extensive woods. The flowers (Fig. 7.5) vary in colour from dull purple to greenish, and are pollinated mainly by common wasps (Vespula spp.) which are sometimes attracted to the flowers in considerable numbers, perhaps in the first instance by scent. The colour of the flowers is reminiscent of the dingy brownish-purple of the wasp-pollinated figworts (Scrophularia spp.) (Chapter 6, see here and here). The mechanism of pollination is similar to that of the marsh helleborine, but the smaller lip is not hinged in the middle and removal of the pollinia depends entirely on the insect’s head striking upwards against the rostellum as it backs out of the flower; the more protuberant rostellum no doubt aids in bringing this about. This species can also be self-pollinated. According to Hagerup (1952), pollen grains which fall onto the rostellum are trapped by its viscid secretion, which later spreads out over the stigmas, where the pollen grains germinate and bring about fertilisation; Waite et al. (1991) found substantial levels of selfing, especially in short, few-flowered inflorescences. In common with orchids known to be regularly selfed, the broad-leaved helleborine shows remarkably regular production of well-developed capsules, nicely graded in size as they mature in succession from the bottom of a long flower-spike to the top.

Fig. 7.5 Flowers of broad-leaved helleborine (Epipactis helleborine).

The helleborines of the related genus Cephalanthera illustrate the way in which the Epipactis type of pollination mechanism probably originated. In size and structure the flowers are not unlike those of Epipactis, but the centre stigma lobe forms no more than a rudimentary rostellum and the pollen grains are only weakly bound together by a few elastic threads. The narrow-leaved helleborine (C. longifolia), which is distributed very widely across Eurasia, is mainly pollinated by small bees. Dafni & Ivri (1981b) observed numerous visits by Halictus species in Israel. Its white flowers (fragrant there, but apparently not so in northern Europe) provide no nectar; visiting bees are presumably attracted by the scent and the ‘pseudopollen’ of the papillose yellow-ridges on the lip. The flowers open rather widely, but the narrow tubular space between the lip and the column forces an insect penetrating the flower against the stigma, which is covered with a copious sticky secretion. Leaving the flower, the insect brushes past the anther, which arches over the front of the stigma, and the friable pollen adheres to the stigmatic secretion smeared on its back. The anther has an elastic hinge at its base and springs back to its original position as soon as the insect has gone. It is arguable whether the lack of a developed rostellum, and other features of the Cephalanthera flower, are primitive or degenerate, but the flower nicely illustrates how the Epipactis condition might have evolved from that seen in ordinary flowers with friable pollen and sticky stigmas. It is particularly interesting that the sticky stigmatic secretion serves to stick the pollen to the visiting insect, because it is the sticky secretion of the rostellum – generally thought to be derived from a vestigial stigma – which takes over this function in all the more advanced orchids. Self-pollination evidently does not take place in C. longifolia in Israel, because no seed is set if pollinators are excluded. The red helleborine (Cephalanthera rubra) is also visited by bees, and apparently (to insect senses) mimics tall Campanula species with which it often grows; the orchid sets more seed in localities where Campanula is present. It is curious that the helleborine is pollinated by early-emerging male leaf-cutter bees of the genus Chelostoma, while the Chelostoma females gather pollen almost exclusively from Campanula (Nilsson, 1983c). The self-pollinated white helleborine (C. damasonium) is discussed later in this chapter.

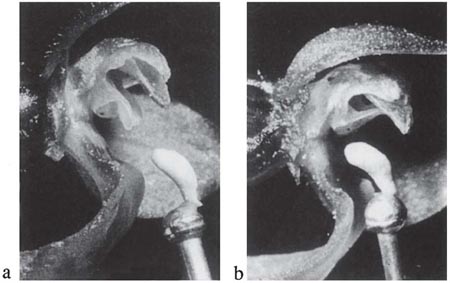

The common twayblade (Listera ovata) (Fig. 7.6 and Fig. 7.8) shows a rather similar mechanism to that of Epipactis, with some interesting differences in detail. The greenish flowers are borne in a long, slender raceme above the two leaves that give the plant its name. They are particularly attractive to ichneumons (a twayblade with a visiting ichneumon appears on the title page of Sprengel’s classic book), especially the males, which visit the flowers in considerable numbers; sawflies and beetles are also frequent visitors (Nilsson, 1981), and these three groups are the principal pollinators. The scent is dominated by two common monoterpenes, linalool and trans-β-ocimene; some of the many minor ingredients may play a part in attracting these particular insects. The lip of the flower is broadly strap-shaped, bent sharply downwards from a point near its base, and deeply notched at the tip. It forms a landing platform leading up to the column; a groove, secreting much nectar, runs from the notch up the centre of the lip. The anther lies behind the rostellum, protected by a broad expansion of the back of the column. As in Epipactis, the anther cells dehisce before the bud opens, and the pollinia are left quite free, supported in front by the concave back of the rostellum. A visiting insect crawls slowly up the narrowing lip, feeding on the copious nectar, which leads it to a point just below the rostellum. On the gentlest touch the tip of the rostellum exudes, almost explosively, a drop of viscid liquid which, coming into contact with the tips of the pollinia and the insect, cements them firmly to its head and sets in a matter of seconds. As the drop of viscid matter is expelled, the rostellum bends sharply downwards, but within 2–3 hours it straightens from its arched position close to the lip, leaving clear the way to the stigma (Fig. 7.7). Now an insect crawling up the nectar groove can pollinate the flower with pollinia brought from another, younger flower. It has been suggested that the almost explosive ejection of the viscid matter from the rostellum may startle the pollinating insects sufficiently to make them fly to another plant before they start feeding again. However, many visiting insects seem little disturbed by the explosion of the rostellum and, as insects generally work up the inflorescence from the bottom, this probably makes little difference to the effectiveness with which cross-pollination is brought about. The most interesting feature of the pollination of twayblade is the way in which a precision mechanism has evolved depending on relatively undiscriminating pollinators; the twayblade probably attracts a greater diversity of insects than any other European orchid. It is striking and curious that an ichneumon or a skipjack beetle (Fig. 7.8) will operate the mechanism neatly and accurately, but the flower evidently does not provide the appropriate cues for orientation of the bees which visit this species casually for nectar and in general are not effective pollinators. The twayblade depends entirely on insects for pollination; self-pollination under natural conditions is apparently rare (Nilsson, 1981). The tiny lesser twayblade (Listera cordata), which grows in boreal and mountain coniferous forests and on moist upland heather moors, has a similar floral mechanism. The principal pollinators in North America are fungus gnats (Ackerman & Mesler, 1979); in California, experimentally emasculated flowers showed a capsule set of 72% which must all have been due to pollinia brought from other spikes (Mesler et al., 1980). However, this species seems to be largely autogamous in north and west Europe.

Fig. 7.6 a–b, Ichneumon wasp (Ichneumon sp.) visiting flowers of twayblade (Listera ovata). a, the insect is sucking nectar from the groove up the centre of the lip. b, the insect has reached the base of the lip and its head is about to make contact with the pollinia.

Fig. 7.7 a–b Twayblade (Listera ovata): a, newly-opened flower; the pollinia have been removed on the head of a pin. b, older flower; the column has curved upwards so that pollinia can now come into contact with the stigmas.

Fig. 7.8 a–c Pollination of twayblade (Listera ovata), by the skipjack beetle Athous haemorrhoidalis: a, beetle with freshly acquired pair of pollinia on its head. b, beetle has arrived at another flower and is beginning to suck nectar from the groove on the lip. c, pollinia have come into contact with the stigma to which pollen is firmly adhering.

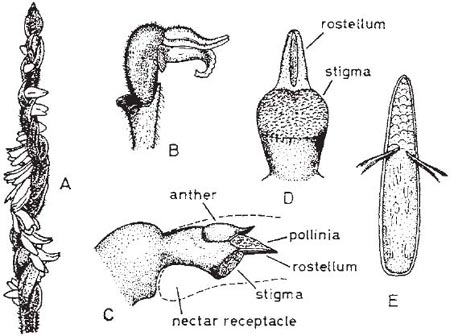

The Lady’s tresses orchids and their relatives (subfamily Spiranthoideae) make up a rather distinctive, largely tropical, group. Autumn Lady’s tresses (Spiranthes spiralis) is an attractive though inconspicuous little orchid locally common in central, western and southern Europe in short turf in late summer. In the south of England the leaf-rosettes die down about May, and the leafless flower spikes appear in August or early September, just before the new season’s leaf-rosette emerges beside them. The small, tubular, sweetly-scented whitish flowers are borne in a spiral on the upper part of the stem, giving a plait-like appearance, hence the English name of the plant. The flowers project almost horizontally from the stem and never open widely (Fig. 7.9). The rostellum is a slender flattened structure, projecting forwards above the stigma. The central part of its upper surface consists of an elongated mass of thickened cells forming a wedgeshaped viscidium (which Darwin called the ‘boat-formed disc’) to which the tips of the pollinia are attached; the viscid matter on its underside is protected by the delicate membrane of the lower surface of the rostellum. At a touch, the membrane splits down the middle and around the edges of the viscidium, exposing the viscid matter and leaving the viscidium free but supported between the prongs of a fork formed by the sides of the rostellum. In a newly-opened flower, the column lies close to the lip, leaving only a narrow passage for the tongue of a bee visiting the flower to reach the nectar in the cup-shaped base of the lip. The flower cannot be pollinated, but the bee inevitably touches the lower surface of the rostellum, and the ‘boat-formed disc’ with its attached pollinia becomes cemented to the upper side of its proboscis. Following removal of the pollinia, the remains of the rostellum wither and the column and lip slowly move apart, leaving the stigma freely exposed to pollen brought by a visiting bee from another flower. The flowers at the bottom of a spike always open first, and those at the top last, so that while the most recently-opened flowers at the top of the spike have pollinia waiting to be removed, those at the bottom of the spike are ready for pollination. The principal visitors are bumblebees (Fig. 7.10), which invariably start at the bottom of a spike and work upwards, visiting flowers in succession until they reach the top and fly off to repeat the process on another flower-spike, so cross-pollination is practically assured. The flowers appear to be quite freely visited. In southern England, Darwin observed visits by bumblebees at Torquay, and visits by bumblebees are frequent at a population on the university campus in Exeter (MCFP), where a good deal of seed is set. Visits by honeybees have been observed at Exeter and in Gloucestershire (K.G. Preston-Mafham), where the flowers were also visited by solitary bees (probably Andrena sp.); and pollinia of S. spiralis were seen on an unidentified small solitary bee in Dorset (MCFP). The floral mechanism of temperate North American species of Spiranthes is essentially similar. Bumblebees are the principal pollinators of most of the species, with leaf-cutter bees (Megachilidae) playing a minor role (Catling, 1983).

Fig. 7.9 Autumn Lady’s tresses (Spiranthes spiralis). A, inflorescence. B, single flower, with lower sepal removed. C, detail of column; the broken line indicates the outline of the perianth. D, front view of column. E, disc with pollinia attached. B–E after Darwin.

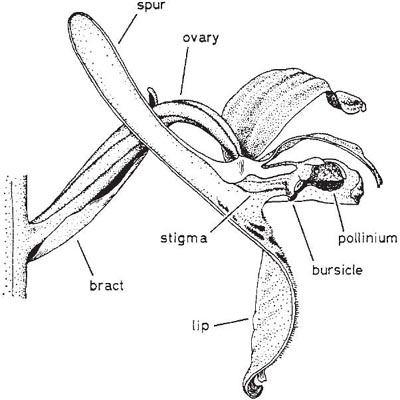

The species which Darwin took as the first example in his book, the early purple orchid (Orchis mascula) occurs almost throughout Europe and is surely one of the best known of all orchids. In Britain, it is often common in woods and pastures and along roadsides in spring and early summer, with its bright purple flowers borne above rosettes of dark-spotted leaves in a rather loose spike which may be anything from 5 cm to 40 cm or more tall. The flowers emit a rather strong and, to our senses, unpleasant scent, due mainly to monoterpenes, especially pinenes, myrcene and trans-β-ocimene (Nilsson, 1983a). The lip is broad, flat or somewhat reflexed at the sides, slightly lobed, and with a long stout spur at its base (Fig. 7.11). The two lateral sepals spread widely, while the upper sepal and the two upper petals form a hood over the single anther, which stands erect just above the wide entrance to the spur. The pollen grains are aggregated into small compact masses (massulae) which are bound together by slender elastic threads into a pair of club-shaped pollinia; the elastic threads run together at the base to form the slender stalks (caudicles) by which the pollinia are attached to a pair of sticky discs, the viscidia, formed of rostellum tissue. The rostellum forms a protective pouch, the bursicle, enclosing the viscidia immediately over the entrance to the spur. Just behind this, forming the upper side of the throat of the spur, is the sticky stigmatic area.

The anther cells open even before the flower expands, so that the pollinia are quite free within them. An insect visiting the flower lands on the lip, and inserts its proboscis into the spur. In doing so, it can hardly avoid touching the pouch-like rostellum. At the slightest touch this ruptures along the front, and the bursicle is easily pushed back by the insect’s movements, exposing the sticky discs attached to the bases of the pollinia. Almost infallibly, one or both will touch the insect, and stick firmly to it. Curiously the spur contains no free nectar. Darwin thought that visiting insects pierced the cells of the wall of the spur to feed on the abundant cell sap, but it is now generally accepted that the spur is, as Sprengel believed, merely a sham nectary (Daumann, 1941; Dafni, 1984). Deception, as we shall see, is a recurrent theme amongst the ground orchids. In the few seconds that the insect remains at the 0. mascula flower, the viscid matter sets hard and dry, and the insect leaves the flower with a pollinium, or a pair of pollinia, cemented like horns to its head. To begin with, the pollinia lie in much the same direction as they occupied in the flower from which they came. In this position, if the insect were to visit another flower, they would simply be pushed against the pollinia there. But about half-a-minute after their removal, as the membrane forming the top of the viscidium dries out, each pollinium swings forward through an angle of about 90°. This movement, completed in a time which would allow the insect to fly to another flower, brings the pollinia on the head of a suitably-sized insect (face about 3.2 mm wide) into exactly the right position to strike the sticky stigmas, leaving a layer of pollen massulae on the surface. The remainder of the pollinium remains firmly attached to the insect’s head, and a single pollinium can pollinate several flowers. The whole process is easily reproduced if a well-sharpened pencil is substituted for the tongue of the insect (Fig. 7.12). However, many visitors are larger or smaller than the optimum size, so in practice the mechanism works with less than perfect precision (Nilsson, 1983a).

Fig. 7.11 Early purple orchid (Orchis mascula). Side view of flower with half of perianth cut away to show details of the column.

Fig. 7.12 a–b Common spotted orchid (Dactylorhiza fuchsii). a, pollinia freshly removed from a flower on the point of a pencil. b, pollinia about half-a-minute after removal, now in a position to strike the stigma.

In Britain, Sweden and other parts of northern Europe, the main visitors are queen bumblebees and cuckoo bees (Psithyrus) recently emerged from hibernation, and males of the solitary bee Eucera longicornis, with occasional visits from other solitary bees and Diptera. Farther south in Europe solitary bees are probably the main pollinators; in fact the form of the flowers seems better adapted to these than to bumblebees. The plant appears to be exploiting its superior floral display at a time when the bees are generally inexperienced and have not yet established nests and regular foraging routines, and food flowers of any kind are rather few. Bumblebees and Eucera males alight at the bottom of the spike and visit only one or a very few flowers before flying off. This results in a characteristic rapid decline in fruit-set from the bottom of the spike upwards (Nilsson 1983a). Nilsson found enormous variation in the number of flowers in a spike setting capsules, with population means varying from about 3% to 20%.

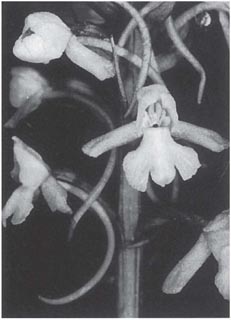

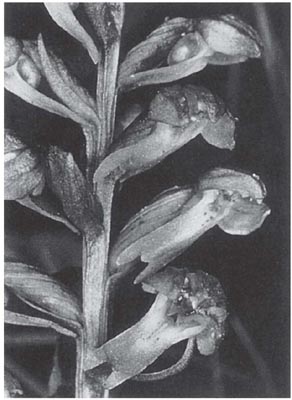

A mechanism identical in all its essentials is found in many other members of the genus Orchis, and in the marsh and spotted orchids (Dactylorhiza spp.) (Fig. 7.12 and Fig. 7.13). These plants are variously pollinated by social and solitary bees and Diptera. The widespread continental European elderflower, or ‘Adam and Eve’ orchid (Dactylorhiza sambucina), with its apple-scented flowers and striking red-purple/yellow colour dimorphism, is pollinated on the Baltic island of Öland almost entirely by bumblebees; the proportion of flowers setting seed varied between localities and years from just over 2% to nearly 50% (Nilsson, 1980). The common and heath spotted orchids (D. fuchsii and D. maculata) appear to be pollinated mainly by bumblebees and honeybees, but various Diptera and beetles (Gutowski, 1990) also visit the flowers and may locally be significant pollinators; according to Hagerup (1951), D. maculata depends for pollination mainly on the drone-fly Eristalis intricarius in the Faroes and Iceland. Honeybees and the bumblebees Bombus lapidarius and B. terrestris were the predominant visitors to a large colony of D. fuchsii near Tring in Buckinghamshire (Dafni & Woodell, 1986). At this site, the bees appeared to be exploiting the copious stigmatic secretion, which contains glucose and amino acids, as a true ‘reward’. On average, 53.7% of the flowers produced capsules, and the proportion in some plants was as high as 90%. As in Orchis mascula, most seed was set in the lower part of the spikes, but this could at least in part reflect nutrient limitation for capsule development. In a population of D. fuchsii at Leith Hill in Surrey, the proportion of pollinia removed, and the proportion of flowers pollinated, was extremely variable (Waite et al., 1991); the proportion of flowers producing capsules ranged from zero to 97%, with a mean of 46.6% in grassland but only 10.6% in woodland. The examples just quoted are instances of rather generalised food deception; the orchid simply has the kind of floral display and scent that would normally be associated with a nectar-producing flower. It is probably significant that many of these orchids are variable in flower colour and form, thus making it more difficult for insects to learn to avoid them (Dukas & Real, 1993). Sometimes the orchid appears to mimic a particular nectar-producing species, as in the case of Orchis israelitica which shares the same flowering season and pollinators – mainly solitary bees – with the common east Mediterranean spring-flowering bulb Bellevalia flexuosa, with which it often grows (Dafni & Ivri, 1981a). A different category of deception is apparent in the orchids that specifically attract males of one particular pollinator; in general this specificity must be due to scent. An example is the east Mediterranean Orchis galilaea, common in Israel, which is pollinated exclusively by the males of the bee Halictus marginatus (Bino et al., 1982); more extreme cases of sexual deception are described later in this chapter. The gaudy pink Mediterranean Orchis papilionacea is pollinated by patrolling males of the anthophorid bee Eucera tuberculata (Vogel, 1972).

Fig. 7.13 Yellow dung fly (Scathophaga stercoraria), bearing a pair of pollinia, on heath spotted orchid (Dactylorhiza maculata).

These deceptive orchids must certainly be derived from nectar-producing ancestors. Only two species of Orchis are known to produce nectar, the widespread European bug orchid (Orchis coriophora) and the similar east Mediterranean O. sancta. In Israel, Dafni & Ivri (1979) found the fragrant flowers of O. coriophora freely visited, especially by honeybees and Nomada, and most of the flowers produced capsules. There are many nectar-producing flowers in genera related to Orchis, and there has been a good deal of adaptive radiation to different pollinators amongst them.

The fragrant orchid (Gymnadenia conopsea), with its slender spikes of heavily scented long-spurred pink flowers (Fig. 7.14), occurs throughout Europe; the smaller, shorter-spurred and even more sweetly-scented G. odoratissima is mainly central European. Both produce copious nectar and are pollinated by Lepidoptera. The flowers of both species are rather small, with a short three-lobed lip. The pollinia are placed so that their elongated viscidia form part of the arched roof of the entrance to the slender spur. The rostellum does not form a bursicle, so the two viscidia are freely exposed to the air. The viscidia become fixed lengthwise to the tongue of a visiting insect, and stick sufficiently firmly even though the viscid matter does not set hard as in Orchis and its near allies – though, as if to compensate for this, the pollinia are more friable and the massulae more easily detached than in Orchis. After removal of the pollinia, the caudicles bend forward and downwards, so that they come to lie almost parallel with the tongue of the insect. In this position they readily strike the two protuberant stigmas, to right and left of the entrance to the spur, when the insect visits another flower. Darwin saw visits by a number of noctuid moths to G. conopsea, and this species seems to set abundant seed; day-flying forester moths (Adscita sp.) are among the visitors to G. odoratissima in Switzerland (MCFP).

Fig. 7.14 Fragrant orchid (Gymnadenia conopsea).

The butterfly orchids Platanthera bifolia and P. chlorantha resemble the fragrant orchids in their naked viscidia. In fact, the pollination mechanism of the lesser butterfly orchid (P. bifolia) (Fig. 7.15a) is very like that of the fragrant orchid, but the rather spidery fragrant white flowers are more obviously adapted to attracting night-flying moths. Pine and small elephant hawkmoths are major visitors to this species in Sweden, but noctuid moths are probably the main pollinators of the shorter-spurred races of P. bifolia that occur in oceanic regions of Europe such as the British Isles (Nilsson, 1983b). The small, round viscidia are placed facing each other close together over the mouth of the spur and the stigmas, and become attached to the tongues of visiting moths. The greater butterfly orchid (P. chlorantha) (Fig. 7.15b), though closely related to P. bifolia and very like it in the superficial form of its flowers, is strikingly different in the form of the column and the disposition of the pollinia and viscidia. The viscidia are placed wide apart, at either side of the entrance to the spur, with the pollinia forming an arch over the large confluent stigmas. The flowers are visited largely by night-flying noctuid moths, but the pollinia become attached to the insect’s head, usually to its compound eyes – which may become so plastered with viscidia that the insect can hardly see. This difference in the structure of the column and spacing of the viscidia places an effective breeding barrier between the two species, and, although they are freely interfertile and overlap both geographically and in flowering time, hybrids are rare. The ‘mechanical isolation’ is reinforced by a difference in scent. On Öland, Nilsson (1983b) found about 22% linalool and 60% methyl benzoate (long known to be attractive to hawkmoths) in the scent of P. bifolia, whereas the scent of P. chlorantha was dominated by lilac alcohols (c. 70%) with c. 25% methyl benzoate.

Fig. 7.15 a–b The common European butterfly orchids, a, lesser butterfly orchid (Platanthera bifolia; south-west England form); the pollinia, close together over mouth of spur, are carried on the tongues of visitors. b, greater butterfly orchid (Platanthera chlorantha); the pollinia, widely spaced at the base, are carried on the compound eyes of visiting moths.

Of 333 visitors to P. chlorantha recorded by Nilsson (1978b) on Öland, 280 were noctuids, belonging to 22 species. The most frequent (106 individuals), and the species carrying the most pollinia, was the plain golden-Y moth (Autographa jota). The tongue length of this species almost exactly matched the most frequent depth of accumulated nectar in the spurs, and its head width was just slightly less than the mean distance between the viscidia. The large and small elephant hawkmoths (Deilephila elpenor and D. porcellus) were also rather frequent visitors on Öland, but with their larger heads are probably less effective pollinators than the noctuids. Pollinium removal (and pollination) can only take place if the insect brings its head up to the mouth of the spur, so longer-tongued moths such as the larger hawkmoths can suck nectar without bringing about pollination. This must impose a selection pressure for adaptation to the longest-tongued of the plant’s major visitors (Nilsson, 1988). Judging from the amount of seed set, the butterfly orchids have an efficient means of pollination. In counts made over three seasons on Öland, Nilsson found seed-set in P. chlorantha ranging from 31% (probably explained by bad weather) to 78%.

Fig. 7.16 a–b Pyramidal orchid (Anacamptis pyramidalis). a, five-spot burnet moth (Zygaena cf. trifolii), visiting a flower; the proboscis of the moth bears several pairs of pollinia. b, another five-spot burnet moth, probing for nectar in an inverted position; the collar-like viscidium encircling the proboscis is clearly visible.

The sweetly vanilla-scented Nigritella nigra of the high pastures of the Alps, with its small, dark red-purple flower-head, is also a butterfly flower, producing nectar in a short, narrow-mouthed spur. As in other head-like inflorescences visited by butterflies (e.g. red valerian and hemp agrimony, see here), the form of the perianth is of little consequence to the pollination mechanism; there is, in fact, little differentiation between the lip and the other perianth members, and in Nigritella (unlike most other orchids) the ovary is not twisted, so the lip of the flower is at the top. Otherwise, the flower works in much the same way as the fragrant orchids, except that the pollinia become attached to the lower side of the visitor’s proboscis.

After these nectar-providing moth and butterfly flowers, the pyramidal orchid (Ana-camptispyramidalis) poses something of an enigma. It has all the marks of a beautifully-adapted butterfly flower. The rather small, pink, sweet-scented, long-spurred flowers are borne in a dense pyramidal spike. The three-lobed lip bears two conspicuous projecting ridges, forming a guide like half a funnel leading into the narrow mouth of the slender spur; Darwin compares them to the sides of a bird decoy. The pollinia are borne on a single saddleshaped viscidium, placed very low on the column over the mouth of the spur, so that the two stigmas (which are confluent in many orchids) are here widely separated. Butterflies and moths, including both day-flying burnet moths (Zygaena spp.) (Fig. 7.16) and night-flying noctuids, visit the flowers in large numbers. The proboscis of a visiting insect is guided straight into the mouth of the spur by the converging ridges on the lip. As it is inserted into the spur it brushes past the bursicle, which moves back at a slight touch and exposes the viscidium. As soon as this is exposed to the air it begins to curl inwards, clasping the insect’s proboscis around which it fits like a collar. Indeed, if the proboscis is slender, the two ends of the viscidium may encircle it completely. Within a few seconds the viscid matter has set and the pollinia are firmly cemented in place, though owing to the curling of the viscidium they now diverge more widely than they did in the anther. After a short interval they begin to swing forward, and soon come to project one on either side of the insect’s proboscis, exactly placed to contact the two stigmas when the insect visits another flower.

Fig. 7.17 Glanville fritillary butterfly (Melitaea cinxia), on pyramidal orchid (Anacamptis pyramidalis), with a pair of pollinia on its proboscis.

Both the number of pollinia removed and the number of capsules produced by the pyramidal orchid suggest that this finely-coordinated mechanism is generally highly effective. Many species visit the flowers, and individual moths often visit this species repeatedly. Darwin remarks on a noctuid moth bearing eleven pairs of pollinia of A. pyramidalis on its proboscis, ‘The proboscis of this latter moth presented an extraordinary arborescent appearance!’ Yet Darwin was unable to find even a trace of free nectar in the spurs of the pyramidal orchid, and was driven to conclude that visiting insects must suck from the intercellular spaces nectar secreted within the tissue of the spur. This is clearly not so in the early purple orchid, in which recent study has confirmed that there is no nectar and the flower depends on deception for pollination, as Sprengel suggested two centuries ago (Nilsson, 1983a). But insects visit the pyramidal orchid so persistently that one can only echo Darwin’s comment (after remarking on a spike of A. pyramidalis which had produced twice as many capsules in the upper as in the lower half), ‘…it appears to me quite incredible that the same insect should go on visiting flower after flower of these Orchids, although it never obtains any nectar,’ (Darwin, 1877). The relation of this orchid to its pollinators calls for critical experimental study.

Fig. 7.18 Frog orchid (Coeloglossum viride).

Fig. 7.19 Chalcid wasp (Tetrastichus conon, female) with a pollinium of musk orchid (Herminium monorchis) attached to each front femur. Scanning electron micrograph, × 64.

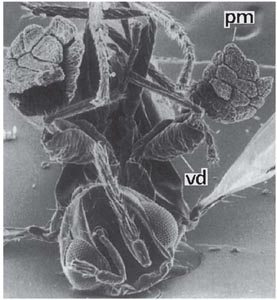

The frog orchid (Coeloglossum viride) (Fig. 7.18) and the musk orchid (Herminium monorchis) have inconspicuous flowers, secreting nectar and pollinated by various small crawling and flying insects. They represent a further variation on the Orchis theme, and provide interesting parallels with the twayblade, which has a similar range of pollinators. The green to brownish-tinged flowers of the frog orchid are like those of Orchis in structure, but the lip is broadly strap shaped with a short broad spur at its base and the remaining perianth segments form a helmet over the column. The two viscidia are rather widely spaced; the stigma is small and lies in the centre of the flower between them. Nectar is secreted in the spur, but in addition there are two small nectaries on either side of the lip close to its base, and almost beneath the viscidia. The lip has a median ridge, which tends to make an insect landing on it crawl up one side or the other, towards one of the drops of nectar beneath the viscidia, rather than up the middle. Feeding at one of these nectaries the insect can easily remove a single pollinium on its head. The forward movement of the pollinium, completed within a minute in Orchis, takes 20 minutes or half-an-hour in the frog orchid – time enough for its rather slow-moving pollinators to visit another spike. The pollen is then readily transferred to the central stigma as the insect explores the nectaries at the base of the lip. Beetles are probably among the commonest pollinators of the frog orchid; soldier-beetles (Rhagonycha fulva) and a small black sawfly have been seen on the inflorescences, bearing pollinia, in Sussex (K.G. Preston-Mafham). Silén (1906a) observed many visits by beetles of the genus Cantharis in northern Finland, and some visits by ichneumons and other insects. The smaller yellowish-green flowers of the musk orchid do not expand widely, and the lip, which has a very short spur at its base, does not differ greatly from the other petals. The flowers are visited by a variety of small Diptera and Hymenoptera; the main pollinators are female parasitic wasps of the genus Tetrastichus (Nilsson, 1979b). Attracted by the characteristic fragrance (probably mainly p-methoxybenzaldehyde, with common monoterpenes), these crawl into the flowers on either side between the perianth segments to seek nectar in the spur. So placed in a semi-inverted position in the corner of the flower, the insect’s leg is immediately below one of the relatively large saddleshaped viscidia, which become transversely attached to the femur, usually near its base (Fig. 7.19). The stigmas are transversely orientated with their broadest parts just below the viscidia, where they receive pollen when the insect visits another flower. Insect visits are essential for pollination, but as Tetrastichus wasps are virtually ubiquitous, seed-set is generally good; Nilsson found that about 70% of flowers formed capsules in southern Sweden.

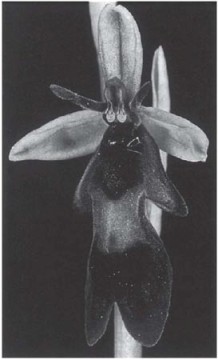

Quite the most remarkable pollination mechanisms among European orchids – and indeed among the most remarkable to be found in any plants – are those of the ‘insect orchids’ of the genus Ophrys. These orchids are well known for the fancied resemblance of their flowers to various insects. What function, if any, this resemblance served was long a matter for conjecture; Darwin was plainly puzzled by it. It was not until the early decades of the twentieth century that it was discovered that pollination in most species is brought about by insects going through part at least of their mating behaviour in response to the flower. This process, often called pseudocopulation, was first elucidated by Pouyanne (Correvon & Pouyanne, 1916; Pouyanne, 1917), who observed the common Mediterranean mirror orchid (Ophrys speculum) for many years in Algeria, where he was Président du tribunal de Sidi-Bel-Abbès. His observations on O. speculum and other species were soon confirmed by those of Col. M.J. Godfery (1925 onwards) in the south of France. Not long afterwards, a similar sexually-deceptive mechanism was described by Mrs Edith Coleman (1927 onwards) in the south-east Australian tongue-orchid Cryptostylis leptochila, pollinated by males of the ichneumon Lissopimpla excelsa. Since then, pseudocopulation has been found in a number of other southern Australian genera, and it may well occur in more genera and species of orchids, and involve a greater diversity of pollinators, in southern Australia than anywhere else in the world. The discovery that two species of Disa in the Cape Province of South Africa are pollinated similarly, D. atricapillata by a sphecid wasp Podalonia canescens, and D. bivalvata by a pompilid wasp Hemipepsis hilaris, adds yet further examples of sexual deception from a different, yet climatically similar, part of the world (Steiner, Whitehead & Johnson, 1994).

Ophrys is represented by many species in southern Europe, north Africa and the Levant. The flowers are similar in general plan to Orchis, but the lip is thick, brownish and velvety-textured, often with metallic bluish markings, there is no spur, and the two viscidia are covered by separate bursicles. Much of our knowledge of Ophrys pollination biology is due to the researches of Kullenberg (1961).

The mirror orchid (Plate 6b; Fig. 7.20B) is a widespread and common Mediterranean species which will be familiar to many people who have spent spring holidays anywhere between Portugal and the Aegean islands. The lip is like an oval convex mirror, of a curious glistening metallic violet-blue colour, with a narrow yellow border thickly fringed with long reddish brown hairs. The thread-like dark red upper petals can be imagined as simulating an insect’s antennae. Pouyanne found, from 20 years’ observation, that O. speculum is visited by one insect only, the scoliid wasp Campsoscolia ciliata, and of that species only by the males. The females ignore the flowers, although both sexes visit other flowers for nectar.

Fig. 7.20 Insect visits to Ophrys flowers. A, male of the solitary wasp Campsoscolia ciliata on a flower of O. speculum. B, male of the solitary wasp Argogorytes mystaceus visiting a flower of the fly orchid, Ophrys insectifera. C, male of the bee Andrena maculipes visiting a flower of O. lutea. After photographs by Kullenberg (1956a, 1961).

Campsoscolia ciliata is rather larger than a honeybee; each segment of the abdomen is fringed with long red hairs. The males appear several weeks before the females, and Pouyanne often saw them during March skimming with a swift zig-zag flight over the dry sunny banks where the wasps make their burrows. The females spend much of their lives underground, hunting for the beetle larvae with which they provision the burrows for their own progeny, and scarcely leave the soil except to mate and feed.

The flowers of Ophrys speculum are eagerly sought out and visited by the males,1 though the insect neither seeks nor finds nectar or other food. Although the flowers have no appreciable scent to us, the males can detect their presence at some distance; Pouanne remarked that if one sat in the sun ‘un petit bouquet d’O. speculum à la main’, the flowers soon attracted the insects, sometimes several hustling one another on the same flower, and apparently oblivious of the observer. The attraction of the flowers resides in the lip; flowers with the lip cut off were completely ignored. Detached flowers laid face-upwards on the ground were as attractive as if they were on the flower spike. If they were laid face-downwards, with the ‘mirror’ hidden, the insects were still attracted but had difficulty in finding the flowers. The wasps were clearly aware of the presence of O. speculum flowers even when they were hidden from sight.

Alighting on the flower of O. speculum, the male Campsoscolia sits lengthwise on the lip, with his head just beneath the rostellum (Fig. 7.20A), and plunges the tip of his abdomen into the fringe of long reddish hairs at the end of the lip with brisk, tremulous, almost convulsive movements, in the course of which he rarely fails to carry off the two pollinia on his head. Pouyanne was struck by the resemblance of the behaviour of the wasp to copulatory movements; later, when he was able to observe the males pursuing the females, he described them alighting on their backs and performing exactly the same movements as they did on the flowers.

Even to our eyes, the lip of O. speculum bears a certain resemblance to the female of Campsoscolia ciliata, with her broad abdomen likewise fringed with red hairs. At first sight the mirror is puzzling, but as Pouyanne realised when he was able to observe the females of Campsoscolia at close quarters, it corresponds exactly with the position of the bluish shimmering reflection on the wings of the wasp when she is resting or crawling over the ground (Correvon & Pouyanne, 1923). To us the resemblance between the wasp and flower may seem crude, but combined with scent and tactile stimuli it attracts the male wasps and elicits the copulation behaviour effectively enough for some 40% of the flowers to produce capsules.

The fly orchid (O. insectifera), which occurs widely from the west Mediterranean countries northwards to Britain and southern Scandinavia, is related to O. speculum. Its pollination, first observed by Godfery (1929) and since studied in detail by Wolff (1950) in Denmark and Kullenberg (1950, 1961) in Sweden, bears many points of resemblance to that species. The flower-spike is slender, typically about 20–40 cm high, and bears up to about ten rather widely-spaced flowers. The lip is rather long and narrow, dark reddish brown with a metallic bluish patch in the centre, and shallowly lobed at the tip (Fig. 7.21). The two upper petals are small, narrow and blackish, forming the ‘antennae’ of the ‘fly’. Perhaps its most characteristic habitat is about wood margins on calcareous soils, but it also occurs in woods, in chalk and limestone grassland, and in open calcareous fens.

Fig. 7.21 Close-up of single flower of fly orchid (Ophrys insectifera).

The only insects known as regular pollinators of the fly orchid are the solitary wasps Argogorytes mystaceus and A.fargei. As in the mirror orchid, the wasps are attracted to the flowers in the first place by scent. Upon settling, the wasp sits lengthwise on the lip – like Campsoscolia on O. speculum – with its head close to the column (Plate 6a; Fig. 7.20B). Often it remains on the flower for many minutes, every now and then restlessly changing its position before settling down again and performing movements which look like an abnormally vigorous and prolonged attempt at copulation. While it is on the flower, the wasp seems quite oblivious of the observer’s presence. Very similar accounts of visits by A. mystaceus are given by Godfcry from the south of France and by Wolff and Kullenberg in Scandinavia, and similar visits have been photographed in south Germany (Baumann & Kunkele, 1982) and in Surrey (G.H. Knight, C. Johnson) and Wiltshire (H. Jones) in southern England. Darwin found that pollinia had been removed from 88 of the 207 flowers he examined; in a small Wiltshire colony visited in early June, 1969, of 13 flowers (on six plants) all but three of the oldest had at least one pollinium removed and eight had been pollinated (MCFP). But it is unusual for more than a quarter of the flowers to be pollinated, and sometimes the proportion is much lower than that, especially in large colonies and in seasons when the orchid is particularly numerous. The flowers are self compatible with their own pollen, but most of the flowers which are pollinated at all must receive pollen from other plants.

Godfery remarked that with only one, apparently accidental, exception, he never saw Argogorytes visit any orchid but O. insectifera; and apart from the two Argogorytes species, O. insectifera received no more than casual visits from other insects. In fact, the Argogorytes species regularly visit umbellifers (Apiaceae) for nectar, and also twayblade (Listera ovata) (Nilsson, 1981). Nevertheless, the relationship between the fly orchid and Argogorytes is so specific that crosses with other species of Ophrys cannot be more than rare accidents. Obviously the fly orchid is closely adapted to Argogorytes. The upper surface of the lip bears a remarkable general resemblance to the back of the female in contour and the nature of its hair covering. The fly orchid has a long flowering season, from early May to the latter part of June, broadly spanning the period when the male wasps emerge. Kullenberg noticed the interesting fact that in a Swedish locality the flowers were visited by A. mystaceus in the early part of the flowering season, but a fortnight later they were being visited by A. fargei.

There is much diversity in detail in the pollination of Ophrys. One of the species studied by Pouyanne and by Godfery (1930) was the widespread Mediterranean orchid O. lutea (Plate 6c). In this plant the lip is brilliant yellow, with a dark raised area in the centre, and a pair of narrow metallic bluish patches on either side of a dark marking near the base. O. lutea flowers in March around Algiers, when even in North Africa calm sunny days are few and far between, and its visitors are much harder to observe than those of O. speculum. The number of capsules produced varies enormously from place to place; in the localities Pouyanne examined it ranged from as few as 3% to as many as 70–80% of the flowers produced. It was in this last favourable locality that Pouyanne was able to witness repeated visits to the flowers by small bees, males of Andrena nigro-olivacea and A. senecionis. The bees made the same kind of movements as Campsoscolia on O. speculum, but in contrast to the insects visiting that species and the fly orchid, the visitors to O. lutea always took up a position with their heads outwards on the flower, so that the pollinia were borne away on the tip of the abdomen (Fig. 7.20C). Evidently to the male bees, the ‘decoy’ represents a female bee sitting head downwards on a large yellow flower. Kullenberg found that by cutting off and reversing the lip of O. lutea he could induce the males to visit the flowers the ‘normal’ way round with their heads next to the column! Ophrys fusca, also a widespread Mediterranean species, works similarly; visiting bees carry the pollinia on the tip of the abdomen (Correvon & Pouyanne, 1916; Godfery, 1927, 1930; Vogel, 1976a; Paulus & Gack, 1981, 1990a).

Another species Godfery observed in the south of France was the late spider orchid, O.fuciflora, which extends from the east Mediterranean to France, and just reaches the chalk of south-east England. The flowers were visited by the large grey males of the bee Eucera tuberculata. The bees became aware of the flowers remarkably promptly and pounced on them, staying only momentarily but quickly and neatly removing the pollinia as they flew away. Kullenberg (1961) observed many visits by Eucera longicornis to plants in experimental cultivation in Sweden, and this bee also effectively pollinated the flowers. Many of the Mediterranean Ophrys species with flowers of the same general form as O. fuciflora are pollinated by bees in a similar way, but these brief visits are easily missed (Paulus & Gack, 1990a, 1990b). A population of the early spider orchid (O. sphegodes; Fig. 7.22), which is very local on chalk and limestone at its northern limit on the south coast of England, showed surprisingly rapid population turnover; individuals lived on average not more than a couple of years, and (at least under good grazing conditions) there was abundant recruitment to the population from seed (Hutchings 1987a, b; Waite & Hutchings 1991). But pollinator visits to this species appear to be infrequent. Godfery (1933) found that of 27 flowers he examined near Swanage, in Dorset, four had both pollinia removed and six had pollen on the stigma; a visit by a bee already bearing pollinia was observed in Dorset in 1975 by Mr J. Moore.

The commonest Ophrys in western Europe, the bee orchid, O. apifera, is regularly self-pollinated, at least in the northern part of its range. Structurally, the bee orchid is very like other members of the genus. Its two significant differences are that the anther cells open a little more widely, and that the caudicles are a little longer and more flexible. Apparently insects occasionally visit the flowers; such visits are probably commoner in the Mediterranean region than in Britain or Ireland. In Morocco, Kullenberg observed visits by Eucera and Tetralonia males (the main species visiting the allied species O. scolopax, O. bombyliflora, O. tenthredinifera and O.fuciflora), but these insects seem often to fail to come into contact with the pollinia and are therefore often not effective pollinators. However, some of the Eucera males observed by Kullenberg visiting the sawfly orchid (O. tenthredinifera) attempted copulation with the labellum but here too failed to reach the pollinia, so in the Mediterranean region there may not be a sharp difference between the bee orchid and some of the related species in this respect. In Britain, too, pollinia are sometimes removed from flowers of the bee orchid; hybrids with the two spider orchids and the fly orchid have been reported, and a correspondent of Darwin’s saw a bee ‘attacking’ a bee orchid flower. However, these are uncommon occurrences, and normally, when the flowers have been open for a day or two, the pollinia fall out of the anther and hang down in front of the stigma. With the spike shaking in the wind, the pollinia swing against the sticky stigma and are held fast. Kullenberg, who made most of his observations on the bee orchid in Morocco, doubted whether self-pollination would take place regularly without the disturbances caused by insect visits, and in north Africa this may be so. The experience of many observers confirms that in the south of England the bee orchid is self-pollinated with a very high degree of regularity. Often a spike of O. apifera can be found with the uppermost flower freshly opened and the pollinia still in their cells, the next flower with the pollinia dangling freely from the column (Plate 6d), and the lowest flower faded, with the pollinia caught against the stigma and a plump capsule developing beneath the flower. In contrast to the other species, almost every flower produces a capsule. O. apifera is often a notably early colonist of suitable disturbed calcareous habitats, but contrary to common belief it is quite a long-lived plant; despite the heavy investment in seed production, the same individual may flower repeatedly in successive years (Wells & Cox, 1991).

The remarkable pollination relationships in Ophrys have stimulated much research into the chemistry of the fragrances produced by the flowers and their insect visitors (Borg-Karlson, 1990). Several conclusions stand out. First, the range of compounds produced by the flowers and insects is similar; both include aliphatic hydrocarbons, alcohols, ketones and esters, benzenoid substances, various common monoterpenes, and sesquiterpenes, especially farnesol and farnesyl esters (but there are compounds in some insect fragrances not matched in Ophrys flowers). Second, there are recognisable broad correspondences between the fragrances produced by individual Ophrys species and those of the insects that visit them. Thus the scents of typical O. insectifera and of Argogorytes are both rich in aliphatic hydrocarbons (O. insectifera subsp. aymonii contains less hydrocarbons and more aliphatic alcohols and terpenes, and is also pollinated by Andrena). In general, the Ophrys species pollinated by Andrena bees have scents rich in aliphatic alcohols, ketones, esters and terpenes, and amongst these there is fair correspondence between the scents of particular groups of Ophrys species and of the particular groups of Andrena species pollinating them. However, these correspondences are by no means exact, and it is clear that the mimicry of insect fragrances by Ophrys is more subtle than straight chemical duplication – and also less than perfectly effective. In field experiments, males were always less attracted to the Ophrys flowers than to their own females. Ophrys pollination thus depends heavily on the newly emerged males early in the flying season before the females appear.

There are many biological parallels between the orchids of the Mediterranean region and those growing in similar climates in the southern parts of Australia, despite the fact that the two floras are not closely related (Dafni & Bernhardt, 1990). Little more than a decade after Pouyanne first recognised pseudocopulation in Ophrys, a similar pollination relationship was found in the south-east Australian small tongue-orchid Cryptostylis leptochila, in this case involving males of the ichneumon wasp Lissopimpla excelsa (L. semipunctata) (Coleman, 1927, 1928a, 1928b, 1929a). The spidery-looking flowers of Cryptostylis are ‘resupinate’, with the narrow, warty reddish-brown lip at the top and curved over the back of the flower (Plate 6c). The male wasps are strongly attracted to the flowers by a scent which is imperceptible to us, and alight on the lip with the tip of the abdomen towards the column. As it attempts to mate with the lip, the visiting insect probes the area around the column with its genitalia, often presenting the flower with its sperm-packet. When the end of the insect’s abdomen comes into contact with a viscidium it carries away a pollinium, which is then brought into contact with the stigma of the next Cryptostylis flower with which the wasp tries to mate. At least five species of Cryptostylis are pollinated by males of the same species of wasp, but the species are apparently incompatible with one another’s pollen and hybrids between them are unknown (Coleman, 1929b, 1930, 1931, 1938).

Fig. 7.23 Pollination of the West Australian orchid Drakaea glyptodon by the thynnine wasp Zaspilothynnus trilobatus. A, The pre-mating posture of the wingless female wasp when calling for a mate, compared with the orchid flower. B, Male wasp tipped against the column in the position required for pollination. C, column; L, labellum; F, female wasp. Reproduced with permission from Peakall (1990).

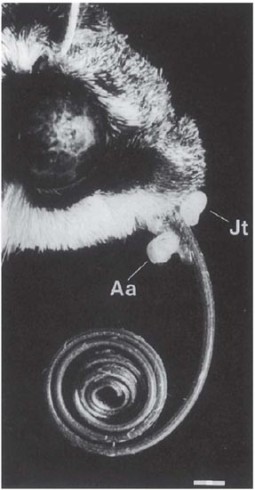

Some very striking Australian examples of pollination by sexual deception depend on thynnine wasps (Hymenoptera Aculeata: Tiphiidae subfamily Thynninae). The female wasps are wingless and, apart from mating (which can take place several times), spend most of their lives underground, searching for the root-feeding scarabaeid beetle larvae upon which they lay their eggs. When ready to mate, the female climbs to a vantage point from which she releases a pheromone that attracts the patrolling, winged males. Final recognition is by sight; the male seizes the female and carries her off. Copulation takes place in flight and is prolonged, the pair visiting flowers at which both sexes feed on nectar while mating. In the west-Australian hammer orchids (Drakaea), the solitary flowers are borne on a slender stem 10–25 cm high. The end of the lip forms a dummy thynnine female, maroon in colour, glossy and usually variously decorated with protuberances or warty excrescences. This dummy is connected to the base of the lip by a slender stalk with a flexible hinge in the middle (Fig. 7.23). The flowers attract the male wasps by odour. Stoutamire (1974) decribes how on several occasions thynnine males followed his car down the road and flew in through the open windows to locate Drakaea flowers on the floor behind the driver’s seat. Peakall (1990) found that flowers of Drakaea glyptodon introduced experimentally into a habitat were discovered by the males of Zaspilothynnus trilobatus within a minute. Once close to the flower, the visitors locate the dummy female by sight, and most alight. Some of the visitors seize the tethered dummy female and attempt to fly off with ‘her’, in doing so swinging back against the column and receiving a pair of pollinia on the top of the thorax – or bringing previously acquired pollinia into contact with the stigma. Peakall found that, following one attempt to carry off a dummy female, a wasp generally did not repeat the attempt with another flower in the immediate vicinity. Different species of Drakaea are pollinated by different wasp species; Stoutamire found that D. elastica was visited by Z. nigripes. As in Ophrys, the number of flowers pollinated varies greatly from place to place; in nine populations examined in 1985 and 1986, the proportion of flowers pollinated ranged from zero to 58% (Peakall, 1990).

Other Australian orchids are pollinated by thynnine wasps in a similar way, including the east-Australian elbow orchids (Spiculaea), and a number of species of the large and varied genus Caladenia, which occurs throughout the southern parts of Australia. Some Caladenia species have colourful sweet-scented flowers visited by small bees in apparent search for pollen or nectar. Other species pollinated by male thynnines have dull-coloured and (to us) odourless flowers; they have mobile, more-or-less lobed lips, bearing a dark raised mark (or a series of dark protuberances) about the size and shape of a female thynnine in the centre, sometimes with leg-like dark markings on either side. In eastern Australia, pseudocopulation with thynnine wasps has also been observed in the bird-orchids Chiloglottis (Stoutamire, 1974, 1975), and in the copper beard-orchid (Calochilus campestris) in Victoria.

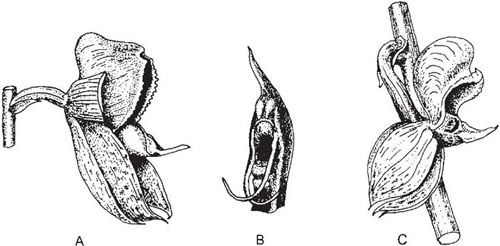

Several other instances of sexual deception have been described from Australian orchids. These include the sawfly Lophyrotoma leachii, visiting the large duck-orchid (Caleana major) (Cady, 1965), and winged male ants (Myrmecia urens) which are the exclusive pollinators of the fringed hare-orchid (Leporella fimbriata) (Peakall, Beattie & James, 1987). A curious case occurs among the greenhood orchids (Pterostylis), where the species of the P. rufa group are pollinated by male fungus gnats which appear to be attracted sexually to the oddly insect-like small brown lip. The lip is irritable, and when triggered by an insect touching the sensitive base it snaps smartly upwards (Fig. 7.24). This traps the visitor with its back against the column, and if the insect is carrying pollinia these are thrown into contact with the stigma. The column has two wings near the tip which project towards the lip, and the only way the insect can escape is by pushing between these wings with its back towards the column, picking up pollinia on its thorax as it does so. A different species of insect appears to be responsible for the pollination of each species of Pterostylis (Coleman, 1934; Sargent, 1909, 1934; Beardsell & Bernhardt, 1983).

Fig. 7.24 a–b Flower of the rufous greenhood orchid (Pterostylis rufa); Eltham, Victoria. In a the lip is in its normal position; in b, following stimulation, it has swung up against the column × 3.5.

There are perhaps 20,000 species of orchids. Most of them grow in the tropics, where probably nearly three-quarters of them are epiphytes on the branches of the forest trees, especially in the tropical mountains. It is clear that our knowledge has only begun to scratch the surface of the pollination biology of these plants. However, a few generalisations can probably be made. First, the kind of highly specific relationships that have figured prominently in the earlier parts of this chapter do occur throughout the orchids (for example, the Andean Trichoceros antennifera, pollinated by tachinid flies, and its relatives are tropical American instances of sexual deception), but they are probably the exception rather than the rule. Many orchids provide nectar or other reward and are ‘normally’ pollinated by bees, moths or other visitors (van der Pijl & Dodson, 1966); indeed, some are quite promiscuous and are pollinated effectively by a range of insects. Second, as we have already seen among European orchids, a remarkably large proportion of orchid species, perhaps more than a quarter, practise ‘false advertisement’ and do not reward their pollinators (Dressler, 1993). Third, it is clear that the same sort of pressures for floral diversification seen at work among the zygomorphic flowers described in the last chapter have also operated in the orchids. The paragraphs that follow highlight only a few selected examples.

‘Angraecum sesqipedale, of which the large six-rayed flowers, like stars of snow-white wax, have excited the admiration of travellers in Madagascar, must not be passed over. A green whip-like nectary of astonishing length hangs down beneath the labellum,’ (Darwin, 1862b). In specimens sent to him, Darwin measured spurs 11 1/2 inches (29 cm) long, ‘with only the lower inch and a half filled with nectar. What can be the use…of a nectary of such disproportionate length?’ Darwin found when he examined the flowers that for a moth to reach deeply into the spur, it would be forced to push its proboscis through the deep notch in the centre of the rostellum, and only if the moth did this would the pollinia become attached to the thick base of its proboscis. It is thus essential to the pollination mechanism (as in the north-temperate butterfly orchids [Platanthera, see here]) that the flower’s spur should be a little longer than the tongue of the pollinator. Even so, this still implies a remarkably long-tongued pollinator, and Darwin concluded that ‘…in Madagascar there must be moths with proboscides capable of extension to a length of between ten and eleven inches!’ (25–28 cm). His surmise was vindicated by the discovery 40 years later of the hawkmoth Xanthopan morgani subsp. praedicta (Rothschild & Jordan, 1903), which has an average tongue-length of about 20 cm, reaching over 24 cm in some individuals. In fact, visits of this moth to A. sesquipedale have yet to be observed in the field, and there is at least one other hawkmoth in Madagascar, Coelonia solani, with a tongue of comparable length (Nilsson et al., 1985). Several long-spurred orchids in the forests of central Madagascar are pollinated by a long-tongued form of the hawkmoth Panogena lingens, with a tongue averaging about 12 cm; the spurs of the orchids are a centimetre or two longer. Angraecum arachnites (Fig. 7.25) places its pollinia near the base of the visitor’s proboscis on the under side (Fig. 7.26); the pollinia of A. compactum, Jumella teretifolia and Neobathiea grandidierana also become attached to the base of the proboscis but on the upper side, while those of Aerangis fuscata are generally carried on the head and the palps (Nilsson et al., 1987). The orchids and the hawkmoth have almost certainly interacted evolutionarily over a long span of time – an instance of diffuse co-evolution, where the orchids have generated a selective pressure as a group. The individual orchid species may compete for pollination, but also benefit from common support of the nectar requirements of their shared pollinator. A hawkmoth the size of P. lingens probably requires about 1.3 mg sugar (22 J) per minute for hovering flight. Nilsson et al. (1985) calculated that for the long-tongued form of this moth the nectar from a single visit to a flower of Angraecum arachnites would yield enough energy to maintain hovering for about 70 seconds.

Fig. 7.25 The long-spurred hawkmoth-pollinated orchid Angraecum arachnites, growing as an epiphyte in primary forest in central Madagascar. Scale bar = 1 cm. Reproduced with permission from Nilsson et al. (1987).

Fig. 7.26 Head of long-tongued hawkmoth (Panogena lingens), with pollinia of two angraecoid orchid species attached to the base of the proboscis, Angraecum arachnites on the ventral and Jumellia teretifolia on the dorsal side. Scale bar = 1 mm. Reproduced with permission from Nilsson et al. (1987).

Several groups of tropical orchids produce oil as a reward, and are visited by oil-collecting bees (see here and here). These include species of Disperis, pollinated by bees of the genus Rediviva (Steiner, 1989), and related African ground orchids, the dwarf tropical American epiphytes of the subtribe Ornithocephalinae, and others (Dressler, 1993). A good many tropical American orchids are visited by hummingbirds, and various genera of diverse systematic affinity (e.g. Stenorrhynchos [Spiranthoideae] and many Epidendreae), have red or yellow flowers which appear to be adapted primarily to bird pollination.

Other pollination systems are based on deception of one sort or another. Two species of Oncidium are pollinated by males of the solitary bee Centris (Dodson & Frymire, 1961b; Dodson, 1962). The bees usually have a favourite perch near an Oncidium plant, and from time to time take off and hover near the orchid. The flowers are borne in long racemes, and when they are moved by the wind the bee darts in and buffets one of the flowers. The Centris bees appear to hold territories by chasing off all insects which fly nearby. Possibly this is a case of ‘aggressive mimicry’, the bees seeing the flowers as flying insects. As a result of repeated buffeting flights, all the flowers of an inflorescence may be pollinated in a short space of time – but often the bees appear to ignore the flowers altogether. However, the flowers are open for about three weeks, which gives them a fair chance of being visited, though investigators have little chance of seeing pollination take place. The plants are apparently self-incompatible, and often only one flower of a pollinated plant produces a fruit.