![]()

We have already seen in Chapter 7 how, among orchids, there are many unconventional ways of securing pollination, including various kinds of deception. Here we look at further cases of deception in the cause of pollination, including more examples from the Orchidaceae.

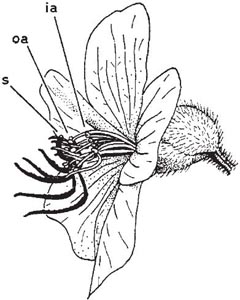

Fig. 10.1 Flower of Tibouchina (family Melastomaceae). The large purple pollination anthers (oa) and the style (s) are shown in black, the smaller yellow food anthers (ia) in white. Pointers to anthers indicate where they join their filaments.

Deceit creeps in by small steps. A mild form of it occurs in some pollen flowers (not providing nectar) that have two types of stamen, one of which provides food while the other dusts visiting insects with pollen. This is a general feature of the larger-flowered members of the family Melastomaceae (Fig. 10.1). Here the flowers are usually purple or pink and the pollination anthers are of a similar colour, while the food-anthers are yellow. The pollination anthers are carried on jointed filaments on the lower half of the sideways-facing flower, serving as a support for an insect collecting pollen from the conspicuous food-stamens while being rather inaccessible themselves. Pollen is released by vibration (buzz-pollination,see below, here, here and here). The flowers are sacrificing some of their pollen to the bees in exchange for pollination. This happens in many plants but here the allocation of pollen to bee-food is clearly defined. Similarly, in many species of the spiderwort family (Commelinaceae) some of the stamens bear modified anthers of conspicuous colour; in some species, these produce no pollen or only a minute quantity. Differentiation of stamens also occurs in Cassia (family Fabaceae) in which the arrangement of floral parts is similar to that of Melastomaceae. Here the pollen is dry and is shed in clouds from pores at the tips of the pollination anthers when these are vibrated by an insect, or as they spring up when the departing visitor takes its weight off them (van der Pijl, 1954). Species of Lecythis and Couroupita in the brazil-nut family, Lecythidaceae, which have hundreds of stamens in the flower, also have two types, one for pollination and one for the pollinators to forage at. The pollination stamens are in the part of the flower where stamens are usually to be found, while the feeding stamens are attached to a lateral appendage which over-arches the flower. The visitor thus has stamens beneath it and stamens above it and its back rubs the pollination stamens. In one species it is known that the feeding stamens produce larger pollen grains than the pollinating stamens (Mori, Prance & Bolten, 1978).

In plants such as these, one can argue that there is an element of deception because the plant is making some of its anthers attractive and others inconspicuous, as well as difficult to manipulate. The insect is not supposed to find all the pollen that is there. The less pollen there is in the food-stamens, the deeper the deception. Even when all the stamens are the same, some trickery may be practised. Several genera of various families have bushy hairs on the stamen filaments which may give the impression of pollen-richness and deflect the insects’ efforts to collect pollen to the wrong place (for example Narthecium and Varbascum) (Vogel, 1978a). In other plants, rather small anthers are borne on enlarged coloured filaments that look like anthers; alternatively the connective (the sterile piece that lies between the pollen-containing parts of the anther) can be blown up into a dummy anther. When pollen is dry and released from holes at the tips of the anthers (‘poricidal’) by the buzzing activity of bees (see here), the anther takes the form of a rigid bottle that does not collapse; this can retain its bright yellow colouring and so continue to lure insects long after it is empty. In the dioecious Begoniaceae and Cucurbitaceae, there are bulky bright yellow stigmas looking similar to the anthers of the male flowers (Agren & Schemske, 1991). The female flowers in these and several other families are rewardless and receive comparatively few pollinator-visits. They rely for pollination on ‘mistakes’ by animals that have already visited male flowers (Baker, 1976; Little, 1983; see here).

The relationship between the plant species and the insect, in the cases just described, is usually not totally one-sided. On the other hand, as we have seen earlier (Chapter 7), some orchids, particularly those that are flower-mimics – either generalised or specialised – do create a totally one-sided relationship with their pollinators. But deception does not necessarily involve the false promise of food. Deceitful attraction of insects that are seeking an appropriate place to lay their eggs is an option taken up by a whole range of plants. The victims are mostly Diptera and Coleoptera. (Some plants actually do provide tissues in which their pollinators breed: these are described in Chapter 11.)

The special features involved in this kind of pollination recur again and again in unrelated plants; they constitute the syndrome of ‘sapromyiophily’ – pollination by insects associated with decaying organic matter. Along with these, we shall now describe also pollination by insects that breed in living fungi.

The main families of plants practising deceit by imitating the ‘brood-place’ are Aristolochiaceae, Asclepiadaceae, Araceae and Orchidaceae. There are two levels of adaptation. In plants on the first level, insects are lured to the flower but are not detained or, if they are, they are released after a short interval. All four families have representatives of this type. Flowers on the second level are more complex; insects are imprisoned for a considerable time, usually 24 hours or more, and the prisons can hold not just one or a few insects, but many. The orchids are not represented on this level; they are dealt with after the other families.

An example on the first level is the genus Asarum in the birthwort family, Aristolochiaceae (Vogel, 1978b, c). In A. caudatum, from North America, the perianth forms an open cup with three brownish flesh-coloured lobes that are drawn out into long points. Tail-like points and dingy purple to brown perianths are features of the syndrome; often the tails are the source of scent and the colour suggests carrion, although here there is no evidence for imitation of flesh. In fact the pollinators are fungus-gnats (Diptera, family Mycetophilidae). Male and female flies come to the flowers and sometimes mate there. In the floral cup below each perianth-lobe are two translucent whitish patches, edged with dark red. Here the female flies lay eggs. These may hatch but the resulting larvae never get beyond the first instar. While the female is laying the eggs, her back touches the plant’s sexual organs in the centre of the flower and causes pollination. There is no scent perceptible to humans but there is evidence that scent attracts the flies. A special feature of the pale patches in the flower is their dampness, resulting from a much higher rate of transpiration than from the neighbouring surfaces. When laying eggs on a mushroom-type fungus, the fly pushes between the gills which are also very damp and may be translucent towards the stalk. Thus the flower seems to imitate the smell, dampness and illumination of the fungus. The number of flies in the habitat builds up in autumn when fungi are abundant. In spring, when Asarum caudatum flowers, there may be plenty of flies but few fungi, and this is the plant’s opportunity to get pollinated by deceiving the flies. It has a creeping habit, grows in shade and bears its flowers underneath the leaves.

This system works efficiently even when there is no exact imitation of the form of a fungus. However, in spite of this some species of Asarum have longitudinal folds or rectangular chambers formed by a grid of ridges inside the flower, thus giving a closer resemblance to the ‘damp crypts’ between the gills of mushrooms (Vogel, 1978b, c).

The milkweed family, Asclepiadaceae (see Chapter 6), has a very elaborate arrangement for attaching pollinia to the hairs, feet or mouth-parts of insects that come for nectar. In such flowers there is a strong tendency to attract Diptera, which has perhaps led to the evolution of the many deceit flowers in the family. In Stapelia and allied genera, which are cactus-like plants of Africa and southern Asia, the flowers look and smell like bad meat or carcasses, characteristically being flesh-coloured or dark purplish red, often covered with hairs, and often of large size – up to 40 cm across (Plate 5c). The largest genera of this type, Stapelia, Caralluma and Huernia, comprise about 250 species, among which there is extensive variation in colour, patterning, type and distribution of hairs, and surface sculpture of the corolla (White & Sloane, 1937). Much of this variation suggests adaptation to pollinators with specific requirements, and there would seem to be a possibility of interesting research into the instinctive requirements and sensory discrimination of the flies that pollinate these strange flowers. When cultivated in Britain the flowers attract muscid and calliphorid flies, which lay eggs in them. These are easily seen, usually near the centre of the flower where presumably the pollinia clip on to the insects.

In the Arum family (Araceae) there are again non-trapping deceit flowers that attract fungus-gnats. In the Mediterranean genus Arisarum there is one species that does not closely imitate a fungus, and one that clearly imitates one in a most perfect way. The first is A. vulgare, which has a striped hood and a club-shaped spadix appendage (see later for details of the inflorescence of Araceae); the second is A. proboscideum, the mouse plant, in which the spadix appendage is the fungus-mimic (Plate 5d). Vogel (1978b, c) found that here, too, the chambered surface of the ‘fungus-cap’ and the neighbouring internal surface of the spathe were moist. Below the moist zone, the surface carries a powdery wax on which the flies cannot walk. The base of the spathe is brightly lit, so flies apparently walk downwards and then fall. The bright light may delay their departure somewhat, but flies are rarely found inside the chamber so it seems they are not effectively imprisoned. The flies’ eggs are found on the spadix appendage of A. proboscideum. This plant also has a tail (hence ‘mouse-plant’), here developed from the tip of the spathe. The flies found by Vogel were Mycetophilidae and, in A. vulgare, also Sciaridae. Strangely, it has been found that A. vulgare attracts hardly any pollinators and reproduces mainly by small tubers (Kroach & Galil, 1986).

We can now move on to look at members of these same families that are on the second level of adaptation, imprisoning their pollinators for a time. In this group, most flowers of Aristolochiaceae and inflorescences of Araceae are protogynous and depend for pollination on insects arriving with pollen; later they shed their own pollen all over the insects and then release them. Protogyny is not needed by the Asclepiadaceae, with their precise pollination arrangements.

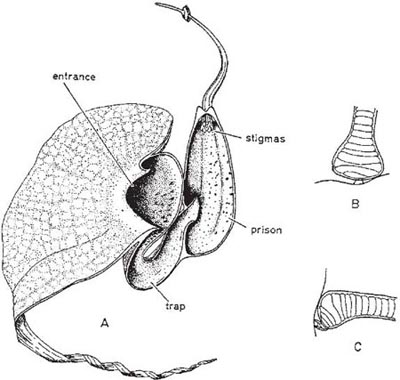

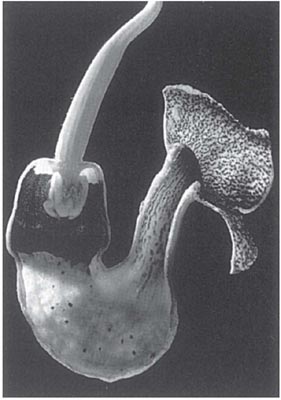

In the large genus Aristolochia (a more advanced member of its family than Asarum) the plants trap insects in their specially modified tubular perianths. In the European A. clematitis (birthwort) the perianth is greenish-yellow and 3.5 cm long, including the tongue-like lobe at one side of the mouth (Fig. 10.2). Biting-midges and other small flies are the pollinators, being attracted by the smell of the flower and alighting on the tongue. If they enter the tube they fall because the cells that line it form downwardly-directed conical lubricated papillae; pinching a papilla with the claws forces the foot off the tip. Once the insects have fallen, their escape is prevented by long hairs that can bend downwards but not upwards. A clear translucent ring round the reproductive organs falsely suggests a way of escape and ensures that the flies effect pollination. When the prisoners are due for release, the tube becomes horizontal or drooping and the hairs and papillae shrivel (Knoll, 1956; PFY). More complex structures are found in two South American species of this genus, A. lindneri and A. grandiflora (Fig. 10.3 and Fig. 10.4). In both species there are conspicuous perianth lobes, a long, tail-like appendage, a dark antechamber or trap, a brighter prison with which the trap connects by a funnel-shaped passage, and a ‘window-pane’ encircling the reproductive organs (better seen in the photograph of A. sipho, Fig. 10.5). They too have internal downwardly pointing lubricated papillae, together with larger hairs. On the day the flowers open, a foul smell is produced by the perianth lobes, and flies are attracted to them and trapped in the prison where nectar is secreted. On the second day no smell is produced, and the stigmas bend together so that they cannot receive pollen. The anthers then open and the prisoners, newly dusted with pollen, are allowed to escape by the widening of the entrance and the shrivelling of the trap hairs. In A. lindneri the purple colour of the trap, which is confined to its inner surface, disappears on the second day, brightening this part of the flower and encouraging the insects to emerge. In the study of this plant by Cammerloher (1933) the commonest visitors were flies of the family Sepsidae. The perianth lobe of A. grandiflora is about 12 cm wide and 20 cm long. The trap is U-shaped, and the hairs in it are all directed away from the entrance; as in A. clematitis these can bend inwards but not towards the entrance, so that the flies slip down the first part of the tube but are helped by them to climb up the second part into the brighter prison. The fly most commonly caught by A. grandiflora was a muscid 4–5 mm long that laid eggs in the prison (Cammerloher, 1923). Two more Aristochia species with U-shaped tubes are shown in Plate 5.

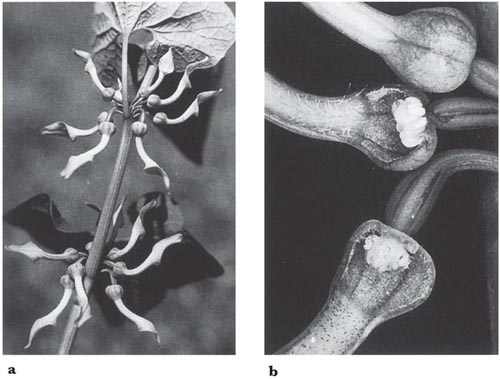

Fig. 10.2 Aristolochia clematitis (birthwort, Aristolochiaceae); a straight-tubed species. a, erect stem with flower clusters at the nodes; b, part of a flower cluster, with two flowers dissected. The upper flower is in the receptive female stage, with the anthers still undehisced; note the stiff downward-pointing hairs in the tube. The lower flower is in the male stage (or later), with the anthers dehisced and the hairs in the tube shrivelled and brown.

Fig. 10.3 Flower of Aristolochia lindneri, another straight-tubed species. A, flower in first stage of anthesis with half the perianth removed; B, flower seen from above (tail-like lobe of perianth foreshortened in this view; as the flowers are borne near the ground the other lobes suggest a faecal deposit); C, a multicellular trap hair seen from above; D, the same from the side, with adjoining papillate cells of trap wall. Shading represents purple colouring; the prison is bright, but an aggregation of dots sets off the ‘window pane’. After Cammerloher (1933) and Lindner (1928).

Fig. 10.4 Flower of Aristolochia grandiflora, with U-shaped tube. A, flower in first stage of anthesis with half the perianth cut away; B, part of a trap hair from above (the swollen base limits movement); C, the same, from the side (the swollen base prevents bending upwards but not downwards). The trap is blackish purple inside and the prison lighter purple with darker freckles; as the hairs in the right-hand arm of the trap are upside down they help flies to climb into the prison. This species is a liana. After Cammerloher (1923).

Fig. 10.5 Sectioned flower of Aristolochia sipho (dutchman’s pipe, Aristolochiaceae), back-lit to show ‘window pane’ round sexual organs; in the female stage with the cushion-like receptive stigmas shielding the anthers. This species is a liana.

More recently some work has been done on Aristolochia in natural habitats in Brazil (Brantjes, 1980). On the whole it was found that different species of Aristolochia trapped flies of different genera or families, though occasionally with a small overlap. When the plants do share the same pollinators, they grow in different habitats. The size of the flower is not related to the size of the insect – the largest species of all, A. cordifolia, attracts the smallest flies. It is the width of the space in the prison around the sexual organs of the flower that is decisive: insects that do not fill the space do not pollinate the flower. The flowers tended to attract all flies but each species actually trapped only a limited range. Various factors were involved in this selection and some of the mechanical ones were not understood. All the Aristolochia species studied had unpleasant scents, but even these had a selective effect; for example, only one Aristolochia out of three trapped dung-frequenting Sepsidae. Although the various Aristolochia species trapped a range of different flies, the overall numbers of the sexes were similar and few eggs were laid in the flowers. Nevertheless, there must have been imitation of some feature of the brood-place; presumably male flies congregate on the materials where females are likely to come to lay eggs and where, in any case, both sexes may feed. Approximate equality of sexes has also been found among the visitors to two species of Arum (see below).

Fig. 10.6 Variation in the flowers of Ceropegia (Asclepiadaceae). The scent-producing areas are shown black, the slide-zones (as far as visible) stippled; shimmering hairs shown when present. Broken lines show lower limits of slide zones. a, C. ampliata; b, C. woodii, c, C. sandersonii × C. nilotoca; d, C. radicans; e, C. elegans; f, C. sandersonii; g, C. euracme; h, C. haygarthii; i, C. stapeliiformis; k, C. robynsiana. Not to scale; some slightly larger than life. From Vogel (1961).

Aristolochia species showing fungus-mimicry also occur. In the more-or-less trumpet-shaped entrance to the flower of A. arborea, there is what looks like a mushroom, complete with stalk. Although this plant is a shrub or small tree, its flowers are borne near the ground, breaking out of the woody stems. The underneath of the cap of the ‘mushroom’ is lamellate on the inner side where it stands over the entrance to the prison. The surfaces are very smooth and it is believed that the flies slip and fall. Once in the prison, they can ascend to a lighted area round the sexual organs of the flower (Vogel, 1978b, c).

In Asclepiadaceae imprisonment is practised by a single large genus, Ceropegia, occurring in Africa, Asia and Australia and comprising herbs, shrubs and climbers, often succulent. The lengthened corolla-tube in these plants forms a trap, similar to that of Aristolochia clematitis, in which flies are imprisoned for a time. The flowers are usually small compared with trap-flowers in other groups (about 10 cm or less long) and are often fascinatingly beautiful, the corolla most often being coloured in delicate shades of green, grey and brown, with elegantly shaped tubes and erect lobes which unite at their tips to give a lantern-like effect (Fig. 10.6). This lantern effect is found in some unrelated fly-trap flowers and appears to be a means of inducing insects to enter (Vogel, gel, 1954). A study of the tiny flowers of Ceropegia woodii (Müller, 1926), published in the same year as Knoll’s investigation of Arum (see later), shows some remarkable parallels between these two unrelated plants, as well as with Aristolochia. As in these other plants, the interior of the flower tube is covered with lubricated papillae (Fig. 10.7), and as in Aristolochia it has hairs pointing away from the entrance. A day or two after the flower has opened, the tube becomes horizontal and the hairs inside shrivel so that the insects can escape. In cultivation in Vienna, this species trapped biting-midges (Ceratopogon), which were apparently attracted by a faint scent produced by the flower. Several species of Ceropegia were studied by Vogel (1961). In each he located the scent-producing area and mapped the area covered by the lubricated papillae (the slide-zone) (Fig. 10.6). He found that in cultivation in Germany five out of eight species attracted none of the available insects, while each of the others trapped female flies. C. woodii trapped biting-midges of the genus Forcipomyia, C. stapeliiformis trapped mainly Madiza glabra of the family Milichiidae, and a hybrid of C. nilotica trapped representatives of two other genera of this family. Thus the scents produced by the flowers are specific attractants to certain insects, and are presumably connected with egg-laying as in the open-flowered members of the family.

Fig. 10.7 Epidermal features of Ceropegia (Asclepiadaceae). A, hooked papillate cells inside entrance to corolla tube of C. woodii; B, blunt papillae from within upper part of tube of same; C, larger, sharper papillae from lower part of tube of same, in section; D, trap hair of C. stapeliformis, seen from above; E, section through papillate epidermal cells within tube of same, with base of a trap hair that is made from a single cell. A–C after L. Müller; D, E after Vogel (1961).

The flies approach with a typical scent-orientated flight and always alight on the scent-producing area; then they investigate the slide-zone, apparently being attracted by the dark interior of the flower, and soon slip into the tube, which is darkened by red colouring on the inner surface in some species. They then pass into the prison, which is usually partly darkened like the tube. The dark part frequently does not show on the outside (as in Aristolochia lindneri, see here, and A. fimbriata, Fig. 10.14, see here). Again, as in fly-trapping flowers of other families, there is often a bright ‘window pane’, forming a ring round the sexual organs. The imprisoned insects, reaching the light end of the chamber, climb the pillar-like inner corona; here they drink from the nectarial cups formed by the outer corona, there being one opposite each groove on the column (Fig. 10.8). After drinking, the fly withdraws its head, and the throat membrane (in Milichiidae) or the base of the labellum (in Forcipomyia), catches in the groove, and receives the clip carrying the pollinia. If the insect already carries pollinia, one of these is caught lower down the groove and pulled off, coming to rest on the stigma. Thus the stimuli which the flower presents to the insects (and the needs to which their responses are related) are successively: smell (egg-laying); dark cavity (egg-laying); bright light (escape from captivity); taste (nourishment). The duration of imprisonment varies from less than a day to four days, according to the species of Ceropegia. Arrangements for release are as in Aristolochia.

Fig. 10.8 Base of flower of Ceropegia woodii (Asclepiadaceae) cut open to show trap hairs, corona with upstanding lobes, a stamen visible between corona-lobes, and the ‘window-pane’ in the base of the prison.

In some species, the hairs inside the tube are specially constructed with a narrow stalk and a wide asymmetric swelling just above (Fig. 10.7). These will thus bend downwards but not upwards or sideways. Each consists of a single cell, although it may be up to 5 mm long. They function in exactly the same way as the similarly-shaped but multicellular hairs of Aristolochia (Fig. 10.3, Fig. 10.4), presenting a striking case of evolutionary convergence.

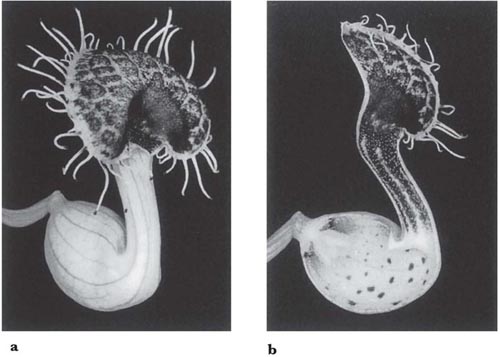

Such remarkable fly-trapping plants occur in the European flora, where much the most widespread genus is Arum, which brings us back to the family Araceae. The curious inflorescence (Fig. 10.9) is borne on a stout stalk; its two main organs are the spadix, which is the axis of the inflorescence, and the leafy spathe. The female flowers form a zone at the base of the spadix and consist merely of ovaries topped by stigmas. Above them is a zone of male flowers consisting only of short-stalked stamens packed together. There are two groups of bristle-like appendages, considered to be sterile flowers. The club-shaped terminal part of the spadix forms a sterile appendix. Pollination is brought about by small insects that become trapped in the pollination chamber during its first, female, stage of development. In the subsequent male stage they are dusted with pollen, after which they are released.

The mechanisms involved in this process were studied by Fritz Knoll (1926), who worked mainly on the Mediterranean species Arum nigrum. The spathe opens overnight and during the following day the spadix produces a strong faecal smell. Insects, mostly dung-frequenting flies or beetles, are attracted in the morning. If they alight on the club of the spadix or inside the spathe they lose their grip and fall, because the surface is papillate, as described for Aristolochia and Ceropegia. Within the spathe, this type of surface is found from the top down to the upper part of the chamber. As they drop, the insects encounter the ring of bristles and if small enough they fall through into the chamber; large insects are arrested and can fly off. If the insects that are trapped have come from another Arum inflorescence, they may pollinate the female flowers (which have receptive stigmas during the first day), probably by climbing upon them in their attempts to escape. The pollen tubes grow quickly into the ovaries and the stigmas then wither, so that by the time the inflorescence sheds its own pollen, self-pollination is impossible. The pollen is shed in great quantity and thoroughly dusts the trapped insects. By the morning of the second day the surfaces of the bristles have become wrinkled, the papillae on the rest of the spadix have shrunk and scent-production has ceased. The change to the surfaces allows the insects to escape, and if they are then trapped by an inflorescence in its first day they can cause cross-pollination.

Fig. 10.9 Lords and ladies (Arum maculatum, Araceae). a, inflorescence at flowering time; b, inflorescence cut open on the second day of flowering, with darkened stigmas, dehisced anthers and numerous trapped owl-midges, Psychoda, sprinkled with pollen.

Knoll carried out experiments using imitation spathes of coloured glass. The inner surfaces of these were dusted with talcum powder, which made it impossible for insects to cling to them. The models, when provided with real Arum nigrum spadices, caught just the same kinds of insects as the real plants, though fewer of them, apparently because the smell of the detached spadices was weaker. These models also demonstrated the principle of capture by falling: it had earlier been thought that the insects entered the chamber voluntarily, to seek shelter and warmth. The models were also used to show that the attraction of the pollinating insects from a distance is purely by scent. Light coloured and dark coloured spathes gave identical results, and Knoll concluded that the colouring of very dark spathes (as in Arum nigrum) or very light ones (as in A. italicum) was only significant in so far as it made the spathes stand out from their surroundings and so induced insects to alight.

A feature of the spadix of Arum, which has long been known, is that it generates heat. This led to the theory that it was the warmth that attracted insects to enter the chamber. Knoll performed experiments with models having an artificial spadix which was electrically heated; this showed that the heat was no attraction. The rapid respiration which gives rise to the heating uses several grams of starch in the course of a few hours, which is out of all proportion to the metabolic effort required to generate the few milligrams of malodorous compounds (ammonia, amines, amino-acids, skatole and indole) that are produced (Fig. 10.13). Probably the main function of the heating is to help vaporise these compounds and intensify their dissemination (Meeuse, 1966). The smell itself is a purely deceptive attraction; the insects receive no food from the Arum, apart possibly from drops of a sweet secretion from the withered stigmas.

Arum maculatum (cuckoo pint, or lords and ladies), which occurs in Britain, has essentially the same mechanism as A. nigrum, but the heating of the spadix and scent production are at their height during the afternoon and evening. The pollinators are small flies of the genus Psychoda (family Psychodidae), of which large numbers may be found in the chamber (Fig. 10.9B) (Grensted, 1947; Knuth, 1906–1909; Müller, 1883; Prime, 1960). However, a single insect that has visited another compatible inflorescence of this self-incompatible plant may carry enough pollen to fertilise all the ovaries in one spathe (Lack & Diaz, 1991). Even so, in England fruit-setting may be limited by shortage of pollinators. Lack & Diaz also found that the stigmatic exudate of A. maculatum had a sugar concentration (sucrose-equivalent) only slightly higher than that of the exudate from cut stems, and that the flies did not drink it; indeed, it is reported that adult Psychoda do not feed.

Arum conophalloides from south-west Asia has a scent which attracts blood-sucking midges of the families Ceratopogonidae and Simuliidae. One spathe of this species which Knoll examined contained 600 Diptera, of which 461 were identified; these were females of three species, one of which was represented by 427 insects. Evidently the attraction of these plants is both effective and highly specific. Counts of insects trapped by A. dioscoridis and A. orientale revealed approximate equality of the sexes (Drummond & Hammond, 1991).

It was in other genera of this family that the function of ‘window panes’ was first discovered. In addition, in some tropical Araceae, insects are induced to enter the trap by the bright appearance of the interior of the spathe, viewed from the entrance. The tissue of the spathe seems to reflect and refract the light to produce this concentration of illumination, which is enhanced by dark surrounding colours. This effect was described in Arisaema laminatum by van der Pijl (1953) and is seen in Plate 5d. In the aquatic Cryptocoryne griffithii, both ‘window panes’ and a bright entry are found (Fig. 10.10). In another member of this family, Amorphophallus titanum, insects are trapped by being prevented from climbing to the top of the spadix by an overhanging ridge; this has such a sharp edge that the large beetles which are reported to pollinate the flowers fall off when they try to negotiate it (this plant also receives visits from Trigona bees). The species Typhonium trilobatum, on the other hand, is pollinated by minute beetles not more than half a millimetre long. They enter the spathe in the early morning and, after they have reached the female flowers at the base, the spathe becomes constricted just above them, making them captive. On the second day, pollen is shed and collects above the constriction; after this the constriction opens slightly and the insects crawl out through the mass of pollen. The trapping of fungus-gnats by Arisaema has already been mentioned, and there are degrees of fungus-imitation in this genus also. The way the hood of the spathe is illuminated may suggest the cap of a mushroom, while the striping in the tube may suggest gills. In more extreme cases, the inner surface is chambered or there is a visual imitation of a fungus by the spadix-appendage (species involved include A. utile, A. griffithii, already mentioned, and A. costatum) (Vogel, 1978b, c).

Fig. 10.10 Inflorescence of Cryptocoryne (Araceae). A, C. griffithii, whole inflorescence with entrance turned away from the viewer and spathe cut away below to show prison; B, view into brightly-lit entrance of same; C, inflorescence of C. purpurea in which the spathe is white outside, the throat yellow and the tip warty and purple inside. A after McCann (1943), B after Vogel (1963), C after W.H. Fitch in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, t. 7719.

A one-way traffic system is found in this family in the taro (Colocasia antiquorum). Flies, attracted by an unpleasant smell, enter through a gap at the base of the spathe, and a constriction prevents them from going beyond the female flowers. Later the same day the smell fades, and the entrance closes up, imprisoning the insects. At night the flies are admitted to the upper part of the spathe where the pollen is shed, and on the second day this part opens, releasing the insects, now dusted with pollen (Cleghorn, 1913). Another one-way route for pollinators has been described in some Indian Arisaema species by Barnes (1934). In these, the spadix, unlike the spathe, is not slippery, and the insects climb down it, passing over the stamens and stigmas and out of a hole formed by unfurling of the spathe at the bottom. An example is A. tortuosum, which produces both male and hermaphrodite inflorescences. A. leschenaultii and some other species are dioecious, and only the males have the basal opening to the spathe. In the female inflorescences, the flowers are tightly packed and have stigmas that project out to the wall of the spathe. The insects – mainly tiny fungus-gnats (family Mycetophilidae) – push down between the stigmas until they are jammed, and die. These species of Arisaema have a great preponderance of male plants, which evidently reduces the risk of the female spathes being blocked by flies that are not carrying pollen. Larger flies are excluded by a ring of filamentous sterile flowers, as in Arum. For more on aroid pollination, see Meeuse & Morris (1984) and Bown (1988).

Deception by orchids ranges from a generalised floral mimicry on the part of unrewarding flowers, to deceptive sapromyiophily and sexual deceit (leading to pseudocopulation). The subject is mainly dealt with in Chapter 7, but here we give some further account of sapromyiophily in the family.

In order to get insects to operate the specialised pollination mechanisms found in orchids, they are often trapped for a short time and/or manhandled because in general only feeding insects can be made voluntarily to orientate themselves in a particular way on the flower. A good example (Bulbophyllum macranthum) is given here. Others are Cirrhopetalum and Megaclinium (closely related to Bulbophyllum), and species in the unrelated genera Anguloa, Masdevallia (Dodson, 1962) and Pleurothallis (Chase, 1985). Of these, the last three are confined to the New World and the first two to the Old, while Bulbophyllum is found in both hemispheres.

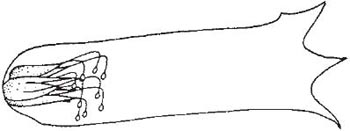

Fig. 10.11 Flower of the orchid Masdevallia muscosa. A, side view; B, side view of column and lip in open position; C, the same with lip in closed position; D, view of distal part of lip from above. Dotted lines show edge of chamber formed by sepals. After Oliver (1888).

Whereas some species of this type, especially those of Cirrhopetalum, attract flesh-flies by producing a bad smell and showing a greater or lesser resemblance to decaying flesh, others seem to be adapted to different tastes, for the flowers of B. macranthum smell of cloves and attract a single species of fly only, while Pleurothallis endotrachys attracts males of the fruit-fly Drosophila (Chase, 1985).

The large orchid genus Paphiopedilum, the tropical counterpart of the bee-pollinated slipper orchid, Cypripedium, is described here. It displays most of the syndrome of sapromyiophily, combined with a one-way passage through the flower for the pollinators. The hoverfly visitors to the spectacular 30 cm-wide P. rothschildianum, in Sabah, Borneo, take about a minute get through the exit passage after laying eggs in the flower (Atwood, 1985).

Some orchids trap insects by a movement of the lip, induced physiologically when the pollinator touches a sensitive area. This effect is called irritability, and an example is provided by Masdevallia muscosa (Oliver, 1888). This New World orchid (Fig. 10.11) has been studied only in cultivation, but the likely pollinators are Diptera. The ridge on the distal, triangular part of the lip is the sensitive area, and touching it causes this part to rise up so that an insect settled on it will be carried into the funnel formed by the united bases of the sepals. The only escape passage now is between the lip and the column, where the pollinia and stigma are situated, and the lip remains in the trap position for about 30 minutes. A very similar arrangement is found in many species of the small terrestrial greenhood orchids (Pterostylis) in Australia, in which some of the perianth parts form a chamber with a hood above, and have their tips drawn out into antenna-like points. The flowers of these species thus look remarkably like miniatures of the fly-trap inflorescences of Arisaema (Plate 5d). This resemblance is heightened by dull green or reddish colouring with darker vertical striping, frequently by the bright-looking interior of the flowers (shown in coloured plates in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine and in Nicholls, 1955, 1958) and by the tip of the narrow, upright lip showing itself at the entrance to the flower like a spadix. The sensitive area is at the base of the lip and often has the form of a filamentous appendage. The insect visitors are mosquitoes and other gnats or midges, and when they spring the lip they are thrown against the column with their backs towards it; if they are carrying pollen they pollinate the stigmas. The column has projections which function like those of Bulbophyllum macranthum (see here), clasping the insect which backs against the column in its struggles and picks up fresh pollinia. There is evidence that in the course of repeated visits to the flowers the insects become intoxicated. A different species of insect appears to be responsible for the pollination of each species of Pterostylis (Coleman, 1934; Sargent, 1909, 1934). (Other species of Pterostylis combine the same mechanism with sexual deceit, see here.)

There are also orchids that show features of the fungus-gnat syndrome. Vogel (1978b, c) has collected a series of examples of detailed fungus-mimicry in the South American genus Masdevallia, where it is the lip of the flower that is modified. It is semicircular or horseshoe-shaped and has radiating gill-like ridges on the side that faces downwards. Scent may be imperceptible or definitely present, and fungus-like or fishy. The fungus-mimics in this genus are now separated into the genus Dracula, but there are other species with a fungoid smell but no visual mimicry of fungi. In Australia, New Zealand and South Asia, tiny plants of the genus Corybas repeat the theme, while in Japan there is a Cypripedium (slipper-orchid) which bears much modified flowers drooping near the ground, in which the entrance to the pouched lip has the appearance of a small mushroom.

Fig. 10.12 Tavaresza grandiflora (Asclepiadaceae). Side view of the dangling knobs formed by lobes of the corona, with the outline of the corona added. Based on Jaeger (1957) and White & Sloane (1937).

The attractiveness to flies of some of the milkweed family is apparently enhanced by their possession of vibratile organs (Vogel, 1954). An example is supplied by the genus Tavaresia (allied to Stapelia), in which the corolla is tubular or bell-shaped and the base of the column is produced into ten long filaments, limp towards their tips and each terminated by a dark red knob (Fig. 10.12). These knobs hang down and constantly vibrate, apparently in response to air movements; the corolla is translucent so that the movement can be seen from all round the flower. Further, some Ceropegia species have large purple unicellular hairs, 3 mm long and with a constricted flexible base. These hairs are found on the borders of the corolla lobes, and hang down in still air; at the slightest breeze, however, they take on a rapid oscillation, producing a strange effect to the eye. Vibratile hairs, of similar size but multicellular in construction, are found in clusters on the tips of the petals of the tropical orchid Cirrhopetalum ornatissimum. In another tropical orchid, Bulbophyllum medusae, each perianth segment is drawn out into a thread many centimetres long, those from each cluster of flowers hanging down and forming a waving plume. The minute, pivoted lips of some species of Megaclinium, also a tropical orchid, likewise oscillate in the wind. (All three of these genera have been mentioned previously on see here.)

The molecular structures of some of the compounds used by sapromyiophilous flowers to attract pollinators are shown in Fig. 10.13. The tail-like structures that are widespread in fly-pollinated flowers may be formed by the perianth or, in the Araceae, either the tip of the spathe or by the appendix of the spadix (Plate 5d). In considering the probable significance of ‘tails’ as alighting places for insects, van der Pijl (1953) drew attention to the propensity of flies for alighting on suspended objects such as fly-papers and electric light bulbs. There is, however, marked variation in the type of ‘tail’, some being erect, antenna-like rods, and others very long threads or ribbons which trail on the ground. An investigation by Vogel (1963) showed that most tail-like structures in fly-trapping or fly-deceiving flowers are scent-producing organs. He found that the scents are often highly specific in their effect on insects, and are responsible for the initial attraction of insects to the flowers – hence the prominent position of the scent-sources. These are called osmophores. Those which produce a very powerful scent during a short period contain big food reserves which are dissipated during the production of scent, and this is frequently accompanied by a pronounced rise in temperature caused by the rapid respiration in the organ. In addition to the classic example of Arum (see here), this kind of heat-production is known in several other species of Araceae, as well as some species of Ceropegia and Aristolochia. There are, however, some species in each of these groups which produce their scent over a period of many days, without any abnormally rapid metabolism.

Fig. 10.13 Molecular structures of some compounds used by sapromyiophilous flowers to attract insects. A, dimethylamine; B, ethylamine; C, putrescine; D, skatole. All of these are found in Arum.

All the special features of the flowers we have been describing contribute to the syndrome of sapromyiophily. Sapromyiophilous and other deceptive flowers operate by stimulating in the insect an instinctive response related to the fulfilment of some need which the flower does not satisfy. Even when food is provided, as in Asclepiadaceae and some Aristolochia species, the attraction of the insect is not normally by means of a food signal. Where male insects are attracted, the signal may indicate both a brood-site (as a place where females are to be found) and a source of food, but then there may be no food.

In this situation, co-evolution of plant and animal is precluded. It is therefore interesting to find that in sapromyiophilous flowers nectar has a high level of amino-acids. Baker & Baker (1975) scored the amino-acid content of many nectars and made a number of group-wise comparisons. They were able to draw general presumptive conclusions of a relationship between amino-acid content and the biology of the flower-visitors. The implication is that where insects have been selecting flowers for the amounts of amino-acid in their nectar, the plants have responded to this in the course of their evolution. The nectars of the group of carrion-fly flowers gave an amino-acid score that was higher than in any other group for which results were published, and about 21/2 times as high as in generalised fly-flowers. Further, Baker, Baker & Opler (1973) observed that the stigmatic exudate that was supped by small flies trapped by two species of Aristolochia had an even higher concentration of amino-acids. As it is adaptively advantageous to insects to shun flowers that will trap them, higher amino-acid content cannot have evolved in response to insect ‘preferences’. What is presumably happening here is that the plant enhances the chance of insects surviving until they reach the next flower.

Sapromyiophilous flowers and fungus-gnat flowers present adaptations to their special method of pollination in both coarse and fine details of the blossom, involving situation, shape, colour, pattern, hairs, surfaces, smells, heating, motile appendages and changes of posture. In these, the different families show most extraordinary parallels. Yet this repetitiveness is accompanied within families by a virtuoso display of variation in visual effects, as expressed in form, texture and colour (see, for Aristolochiaceae, Plate 5a, Plate 5b & Fig. 10.3, Fig. 10.4 & Fig. 10.14, for Araceae, Plate 5d, Plate 5e & Fig. 10.9, Fig. 10.10, and for Asclepiadaceae, Plate 5c & Fig. 10.6). The plant families involved are diverse, the Araceae and Orchidaceae being monocotyledonous and probably very distantly related, the Aristolochiaceae being primitive dicotyledons and the Asclepiadaceae advanced dicotyledons.

Fig. 10.14 Flower of Aristolochia fimbriata (Aristolochiaceae), a further example of the many types of bizarre decoration displayed by sapromyiophilous flowers. a, from the outside; b, with half the perianth removed: this flower has reached the male stage.

Many water-lilies (family Nymphacaceae) are night-flowering and attract beetles. The giant waterlily of the Amazon, Victoria amazonica, is such a plant. The flowers first open in the evening, and are then white and scented; they become heated to several degrees above ambient temperature by their own metabolic activity. Large beetles (Cyclocephala species, family Scarabaeidae, subfamily Dynastinae) (Prance & Arias, 1975) arrive, enter the flowers voluntarily and pollinate the stigmas. Overnight the outer floral parts close up and imprison the beetles, which then cat the starch-containing appendages of the carpels. Next day the flower gradually turns deep purple; the anthers dehisce and the beetles become completely covered with pollen. Adhesion of pollen to the visitors is promoted by the fact that when they eat the stigmatic appendages their bodies become sticky. The flowers re-open in the evening and the beetles fly off and head straight for the newly opened scented white flowers. The old flowers then close up and become submerged. Although the flower manages its pollinators by imprisoning them, it is not clear how far they can be said to be victims of deception because it is not known whether they have other food sources which the plant might be imitating.

An extraordinarily similar syndrome is shown by two giant species of the large tropical aroid genus, Philodendron (Gottsberger & Amaral, 1984). They have precisely timed opening and closing sequences, spells of warming in the spadix, bringing the temperature to as much as 24°C above ambient for up to an hour, and periods of scent emission. The lowest tenth of the spadix is female and the remainder is split into a lower half of wrinkled texture, formed by sterile male flowers, and an upper half of fertile male flowers. Dynastine beetles arrive in the evening and feed on exudates and on the sterile flowers. Next day the spadix enters the male phase, exuding pollen in sticky chains, while the spathe secretes a sticky resin on its inner surface and starts to close. The beetles are thus driven out, being pasted with adhesive and liberally covered with pollen as they go. These two species of Philodendron differ in many details and each attracts a different species of beetle, respectively 2.5 cm and 2 cm long, one being in the same genus as that which pollinates Victoria amazonica. There is clearly no trapping here.