![]()

The Hymenoptera, which includes the bee, are a very diverse group of extreme biological interest, with about 6,200 species in Britain. These insects have four wings, those on each side being held together by a system of easily disengaged hooks. In the female the abdomen terminates in either an ovipositor or a sting. Also characteristic are the well-developed mandibles and the labio-maxillary complex. This is formed by the partial fusion of the maxillae with the labium (Box 5.1); it has a central tongue-like glossa (sometimes bilobed) but we shall use the word ‘tongue’ for the whole complex. The homology of the mouth-parts with those of primitive insects (Box 3.1) is clearer than in the Diptera or Lepidoptera. The order is divided into two sub-orders, the Apocrita, comprising gall-wasps, ichneumon-wasps, bees, wasps and ants, and the Symphyta, a more primitive and less numerous group, the sawflies.

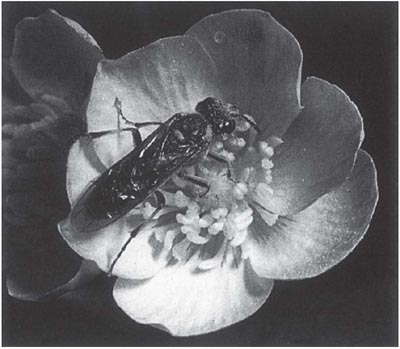

The Symphyta are distinguished from the other Hymenoptera by their lack of a narrow ‘waist’ (Fig. 5.1, Plate 2a). They are somewhat wasp-like in appearance but have proportionately larger wings, usually soft clumsy bodies, and comparatively slow movements. The flower-visiting species range in length from about 5 mm to 22 mm. The larvae of most sawflies are like lepidopteran caterpillars in appearance and live externally on plants. The adults use the mandibles to chew solid food and the tongue to lick up solids. There are three main types of food: (1) insects, (2) moisture (rain, dew, ‘cuckoo-spit’, honey-dew and damaged ripe fruit), and (3) flowers and leaves. The floral materials include nectar, pollen, stamens and petals, and are taken chiefly by females (Benson, 1950). Nectar and pollen have to be well exposed, as the mouth-parts are usually 2 mm long at most. In fact, the flowers most favoured by sawflies are Apiaceae, Rosaceae with large inflorescences, yellow Asteraceae and Ranunculus (Benson, 1950; Willis & Burkill, 1895–1908). Sawflies must certainly be effective as pollinators, and they are often common enough to form a significant fraction of the pollinator fauna, but their benefit to the plants is sometimes offset by the injuries which they do to the flowers. The larvae of sawflies are often closely restricted to certain food-plants, and there is a marked tendency of the adults to visit mainly the flowers of the larval food-plant (Table 5.1). Such attachments are particularly strong with species feeding on willows (Salix), some of them confining themselves entirely to the flowers of the species on which the eggs are laid, even when other Salix species are available (Benson, 1950, 1959).

Fig. 5.1 Sawfly (Tenthredo sp., Hymenoptera Symphyta: Tenthredinidae), on buttercup (Ranunculus sp.).

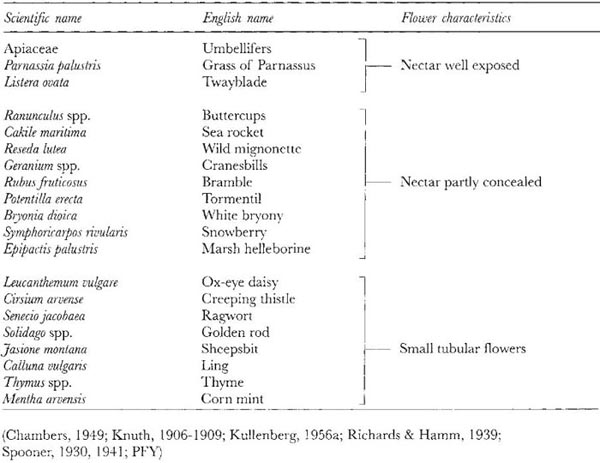

Table 5.1 Flowers visited by sawflies, Hymenoptera-Symphyta (‘L’ indicates larval food-plant of the flower-visiting species).

| Scientific name | English name |

| Some Brassicaceae | Crucifer family |

| Reseda lutea | Wild mignonette |

| Geranium dissectum | Cut-leaved cranesbill |

| Geranium sanguineum | Bloody cranesbill |

| Acer campestre | Field maple |

| Acer pseudoplatanus | Sycamore |

| Rubus spp | Bramble, raspberry, etc. (L) |

| Sedum telephium | Orpine |

| Saxifraga hypnoides | Mossy saxifrage |

| Apiaceae | Umbellifer family |

| Euphorbia cyparissias | Cypress spurge |

| Salix spp. | Sallows and willows (L) |

| Scrophularia spp. | Figwort, etc. (L) |

| Verbascum spp. | Mullein |

| Ajuga spp. | Bugle, etc. (L) |

| Polygonum bistorta | Bistort |

| Galium spp. | Bedstraw |

| Symphoricarpos rivularis | Snowberry (L) |

| Valeriana officinalis | Common valerian |

| Scabiosa spp. | Scabious (L) |

| Cephalanthera longifolia | Narrow-leaved helleborine |

(Jones, 1945; Knuth, 1906–1909; Kugler, 1955a; Poulton, 1932; Willis & Burkill, 1895–1908; PFY)

One of the more striking flower-visiting sawflies is Abia sericea (family Cimbicidae), a large blackish insect with a green metallic sheen and a wrinkled abdomen; it has been recorded as frequent at small scabious (Scabiosa columbaria) (Chambers, 1947). Many members of the large family Tenthredinidae visit flowers; an example is Tenthredo arcuata, a black insect with yellow bands, which was the sawfly most commonly recorded at flowers by Willis & Burkill (1895–1908) in their observations in the Cairngorms; it is a regular visitor to buttercups (Ranunculus spp.) (Harper, 1957). Another member of the family that visits buttercups is Athalia bicolor, a medium-sized species which is black except for the orange abdomen – a very common colour-pattern among sawflies. Sawflies (together with ichneumon-wasps, see later) have been found to be important pollinators of the twayblade orchid (Listera ovata) in Sweden (Nilsson, 1981). In both groups, more males than females were found visiting this and other flowers, even though in general the populations of these insects show a female-biased sex-ratio. One sawfly species in Australia effects the pollination of the orchid Caleana major by the process of pseudocopulation, in which the males act as if mating with the flowers, which in form and scent resemble the female insect (see here & here). The precise cise positioning and the movements involved in mating make it a suitable process for exploitation by orchids, since their method of pollination, involving the transfer of pollen masses to the stigma (Chapter 7), also requires accurate positioning of the insect.

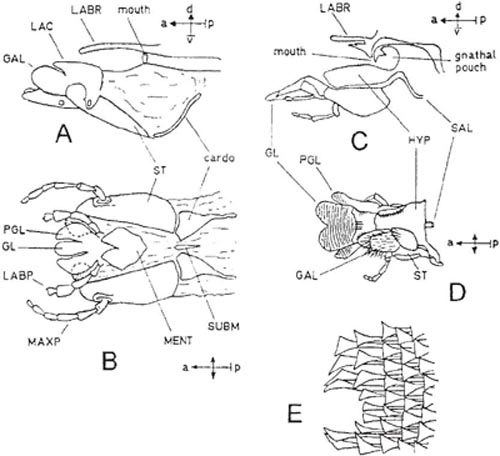

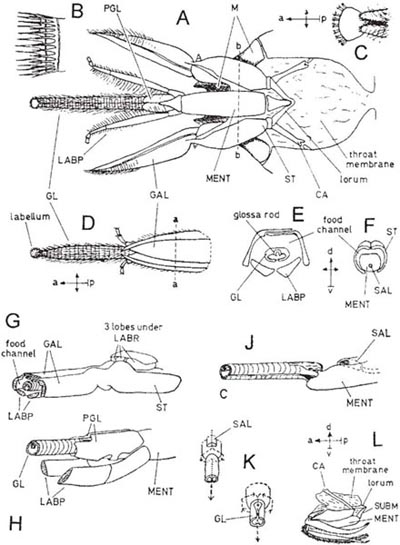

Diagrams A and B (after Bischoff, 1927) show the relatively primitive condition of the labio-maxillary complex in a sawfly (Cimbex). The social wasp Vespula is not very different (C, D – with the right maxilla removed; after Duncan, 1939), but the glossa is bilobed and, like the paraglossae, covered with flattened hairs among which liquids can be imbibed (E). This hairy part of the tongue can be brought upwards into a pouch formed by the hypopharynx, maxillae and epipharynx, and suction can then be applied to draw the imbibed liquid into the mouth. A filter is formed by the fitting together of comb-like rows of hairs on the hypopharynx and on the galeae of the maxillae. Another filter is formed by a similar row of hairs across the narrow slit-like mouth, and this prevents all but microscopic particles from entering the mouth. Material filtered out by this second comb is temporarily stored in the pouch. Key to lettering: GALea, GLossa, HYPopharynx, LABial Palp, LABRum, LACinia, MAXillary Palp, MENTum, ParaGLossa, SALivary duct, STipes, SUB-Mentum.

The larvae of the stem-sawflies (family Cephidae) live in the stems of plants, including those of cereal grasses; the adults are small or medium-sized with long and very slender bodies, and in colour they are black with narrow yellow bands. The adults visit flowers, especially Ranunculus spp.

The great majority of the Hymenoptera belong to the sub-order Apocrita and may be divided into those with stings (Hymenoptera-Aculeata) and those without (sometimes referred to as Hymenoptera-Parasitica, since most of them are parasitic). The stingless Hymenoptera, which can be referred to as wasps of various kinds, are very numerous in species but are not of great importance in pollination. The flower-visiting species are distributed across about ten families.

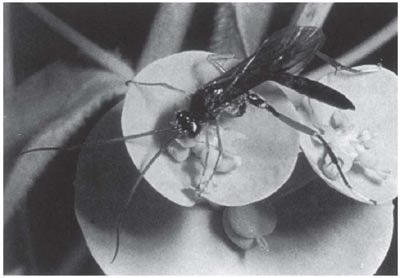

The most noticeable of the Parasitica are the ichneumon-wasps (family Ichneumonidae); these are parasitic in the larval stage, usually on the larvae of other insects. Some of the adults are very small, but a good proportion of them are of moderate or large size (with a body length of 1–2 cm). They are particularly slender insects with long antennae and long legs (Fig. 5.2), and they are usually very active. They consume sap, honey-dew, nectar and pollen; the nectar includes that obtained from extra-floral nectaries (see here) and the pollen that has been trapped by dew-drops (Leius, 1960). The mouth-parts, even of quite large species, are usually under 1 mm long; they are rather similar to those of sawflies but the glossa is larger than the paraglossae.

The Ichneumonidae visit much the same flowers as the short-tongued Diptera (Table 3.3). Laboratory experiments carried out in Canada with three species of ichneumon-wasp showed that one of them would visit only Apiaceae, among plants of several families offered, while the other two visited various flowers but made most visits to Apiaceae. Such investigations are carried out mainly with a view to finding out the food requirements of Ichneumonidae used for biological control of insect pests, since a lack of suitable food for the adult wasps after their release might lead to failure of projects. In general, any destruction of wild flowers tends to reduce the natural populations of these useful parasites of crop pests (Leius, 1960; van Emden, 1963).

Fig. 5.2 Ichneumon (Hymenoptera Parasitica: Ichneumonidae) feeding at wood spurge (Euphorbia amygdaloides). (See also Fig. 7.6.)

Among the more distinctive of the ichneumon-wasps is the genus Pimpla, the species of which range from about 6 mm to 20 mm long, and are black with brown legs and a transversely wrinkled abdomen. The species of the genera Ichneumon and Amblyteles are also conspicuous, being over 10 mm in length and decorated with bands and spots of cream, yellow and light red in various patterns on the black body. All these insects are common at Apiaceae, especially hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium) and parsnip (Pastinaca sativa), while Amblyteles uniguttatus is one of the ichneumons recorded at twayblade (next paragraph). Willis & Burkill (1895–1908) designated the Hymenoptera-Parasitica as merely injurious but this is erroneous on the evidence of the Ichneumonidae alone.

The twayblade orchid (see here and here) is often given as an example of a rare class of flowers called ichneumon-wasp flowers, and Knuth gives records of six genera of these insects visiting its flowers; it is, however, also visited to some extent by small Diptera and Coleoptera, as well as sawflies (see see here). An Australian species of ichneumon, Lissopimpla excelsa (L. semipunctata), is involved in pollination by pseudocopulation of orchids of the genus Cryptostylis (Plate 6e; see here).

Much less conspicuous among the flower-visiting Hymenoptera-Parasitica are several families constituting the chalcid wasps and gall-wasps, insects that are mostly only 1–4.5 mm in length. One of the largest chalcid wasps, Brachymeria minuta, is easily recognised, having a short, stout shining black body with a pointed abdomen and swollen hind legs. However, most chalcids are moderately slender in form and are usually black with a green or blue metallic sheen (Fig. 7.19). Some chalcids have vegetarian larvae that live in seeds. Included here is the family Agaonidae, which are specialised for living in the tissues of figs which they cross-pollinate in the course of their egg-laying activities (see Chapter 11). The gall-wasps (Cynipidae) are so called because most of them form galls on plants (the rest are parasitic on insects). The eggs of the gall-formers are laid inside the plants and the presence of the larvae stimulates the development of abnormal growths which they then consume. These small insects visit much the same flowers as Ichneumonidae (Harper, 1957; Knuth, 1906–1909; Willis & Burkill, 1895–1908), including three tiny orchids, Hammarbya paludosa (bog orchid), Listera cordata (lesser twayblade – Ackerman & Mesler, 1979) and Herminium monorchis (musk orchid – Nilsson, 1979b) (see also Chapter 7). Kevan (1973) has surveyed the occurrence of parasitic Hymenoptera at flowers in the High Arctic of Canada; he found that flowers were important to them as food sources, and that some of them carried pollen, but they were probably insignificant as pollinators compared with other groups of insects.

Our third group of Hymenoptera-Parasitica is the Chrysididae, which are closely related to the true wasps and have been placed in this position only for convenience of description in this book. These wasps have brilliant metallic colouring: the prevailing pattern is blue or green on the head and thorax and red on the abdomen, giving rise to their popular name of rubytail-wasps. They range in length from 3 mm to 10 mm, are rather scarce, and in habits they are parasitic on the larvae of solitary bees and wasps. The British species, which have short mouth-parts, have been recorded in Britain almost exclusively at the flowers of Apiaceae. However, the members of the continental chrysid genus Panorpes are specialised flower-visitors with a proboscis 6–7 mm long. In this genus the glossa is elongated and rolled at the sides to form a tube, while the galeae of the maxillae are also elongated and cover the glossa.

The Hymenoptera that have stings are classed as Hymenoptera-Aculeata. They mostly build nests in which food for the larvae is stored by the adults, and they comprise the true wasps, the ants and the bees. In many families, however, there are species or whole genera that have the habits of the cuckoo, the adults laying eggs in the nests of other Hymenoptera, and the resulting larvae feeding on the food supply of the rightful owner; such insects are called inquilines. Apart from the inquilines, there is a group of wasp families regarded as the most primitive of the aculeates, which are entirely parasitic on other larvae. This group, the superfamily Scolioidea, is represented in Britain by the large velvet-ant (Mutilla) and several smaller species that visit the same sorts of flowers as the Hymenoptera already described. In most of them, the females are wingless. Also in Scolioidea are large, usually hairy wasps, such as Campsoscolia (Fig. 7.20), noted as a pollinator of the mirror orchid (Ophrys speculum) by pseudocopulation (see here), and a variety of Australian species that also pollinate orchids by pseudocopulation (Jones & Gray, 1974; Stoutamire, 1974) (see here for details, including plant and insect names and further references).

The great majority of the true wasps capture insects or spiders as food for their larvae. Usually the prey is stung or mutilated and stored in cells in the nest, one egg being laid on the food supply in each cell. Sometimes these predatory wasps feed on the juices exuded by their victims, but otherwise they take the same liquid foods as the Hymenoptera-Parasitica, namely sap, honey-dew and nectar. Their nesting requirements are the same as those of solitary bees (see here).

Table 5.2 A selection of the flowers visited by non-social short-tongued wasps of the superfamilies Pompiloidea, Sphecoidea and Vespoidea.

Fig. 5.3 Solitary wasp (Mellinus arvensis, Hymenoptera Aculeata: Sphecidae), on sea carrot (Daucus carota ssp. gummifer).

There are three superfamilies of predatory wasps: the Pompiloidea, the Sphecoidea and the Vespoidea. The family Pompilidae, or spiderhunting-wasps, comprises about 40 species in Britain. With their long legs and slender bodies, 5–14 mm long, they are somewhat ichneumon-like. In colour, they are mostly black with red on the fore-part of the abdomen, but some are entirely black or black with white spots or bands. They pursue their prey largely on foot, skimming the ground in short flights from time to time. Spiderhunting-wasps visit flowers (Table 5.2) but are absent from Willis & Burkill’s (1895–1908) records from the Cairngorms, probably because, like most aculeate Hymenoptera, the Pompilidae require warm conditions. At the beginning of their adult lives, they seem to spend a lot of time feeding on nectar and may briefly be a significant component of the pollinator fauna for Apiaceae. Pseudocopulation is known in Pompilidae (see here).

The family Sphecidae contains most of the non-social wasps and has about 100 species in Britain. The length of the body ranges from 3–25 mm, and its shape is very variable, especially that of the abdomen, whose narrowed fore-end can have many different conformations. The colour may be black (or black with red on the fore-part of the abdomen) but often it is black and yellow, the yellow being either confined to small spots or occurring in large spots or bands so that the insect conforms to the layman’s idea of a wasp (Fig. 5.3).

The flowers they visit are listed in Table 5.2 but most visits seem to be to Apiaceae (see here). The tongue length of two fairly large species measured by Kugler was only 1.5 mm; however, in the sand-wasp, Ammophila sabulosa, it is 3 mm and the sides of the glossa are rolled back to form a tube. This wasp visits a variety of flowers, including bramble, thistles and snowberry. Species of Argogorytes pollinate the fly orchid (Ophrys insectifera) by pseudocopulation, as described here. Like Campsoscolia, but unlike Lissopimpla, Argogorytes carry the pollinia on their heads (Plate 6a; Fig. 7.20).

The Sphecidae, like Pompilidae, are probably significant as pollinators only occasionally. No doubt chiefly on account of their need for warmth they are completely absent from the records of Willis & Burkill (1895–1908), but possibly their ability to avoid capture also played its part. As in the Chrysididae, there is a continental representative of the Sphecidae with an elongated proboscis 7 mm long; this is Bembex rostrata, which is able to obtain nectar from and pollinate the explosive pea-type flowers of lucerne (Medicago sativa).

Fig. 5.4 Mason wasp (Ancistrocerus cf. trifasciatus, Hymenoptera Aculeata: Eumenidae), on hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium).

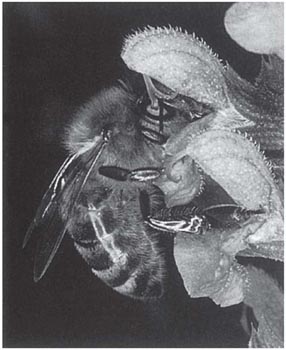

The members of the third superfamily of predatory wasps, the Vespoidea, are distinguished by having the fore-wings folded lengthwise when at rest. They comprise the non-social families Eumenidae and Masaridae, and the social Vespidae. The non-social groups have the same life-history as the Sphecidae. The family Eumenidae includes the potter wasp, Eumenes, with one species in Britain, and the mason-wasps, about 20 species in Britain, belonging to Odynerus and closely related genera. These are all yellow and black (or rarely white and black) wasps, about 8–12 mm in length (Fig. 5.4). Flowers visited are listed in Table 5.2. Eumenes coarctata is found on heaths in Britain, and it probably feeds from the flowers of ling (Calluna vulgaris). Its tongue is 4 mm long, and the glossa is rolled back at the edges to form a tube, as in Ammophila (Kugler, 1955a). This species (males only) has also been found as a visitor to marsh helleborine (Epipactis palustris) (Fig. 7.3, Fig. 7.4), whose dimensions its body fits exactly (Nilsson, 1978b). The Masaridae are almost all flower-feeders, occurring mostly in warm-temperate areas. They collect pollen on hairs on the face and transfer it to the mouth with the forelegs; it is then mixed with nectar in the crop, as in the bee Hylaeus. The one Central European species (Celonites abbreviatus) has a proboscis nearly as long as the body. It visits especially flowers with a lipped corolla, such as Teucrium (Mauss & Treiber, 1994). In California the species visit bee-adapted flowers, such as certain Penstemon species.

In the Vespidae, each colony is founded by a queen, who lays eggs and feeds the offspring as they grow. These offspring are the workers and after they become adult the queen remains in the nest and lays eggs, while the workers bring in the food and extend the nest. In temperate countries, the colony usually dies out in autumn and only the new generation of queens survives the winter. These social wasps are represented in Britain by the hornet (Vespa crabro) and the insects normally recognised by the layman as wasps. In Britain, these comprise several species each of the genera Vespula and Dolichovespula. Elsewhere, there are many slender-bodied members of the family that make nests without an envelope. They constitute the subfamilies Polistinae and Stenogastrinae; a common European example is Polistes.

In Vespula and Dolichovespula the tongue is slightly longer than in most Sphecidae (for description see Box 5.1). Although the adults of Vespula feed the larvae chiefly on insects, they also feed both themselves and the larvae on liquid foods, often obtaining these from flowers. It used to be thought that the larvae were fed only on animal food, but the transport of large quantities of a solution of sugar and honey to the nest was observed by Verlaine (1932b), and it was later shown that sugary fluids are essential to the diet of the larvae of Dolichovespula sylvestris (Brian & Brian, 1952). On the other hand, pollen is not a wasp food (Duncan, 1939).

Fig. 5.5 Common wasp (Vespula germanica. Hymenoptera Aculeata: Vespidae), feeding on exposed nectar of ivy (Hedera helix).

Vespidae visit some of the flowers in each of the groups listed in Table 5.2. Of the flowers with well-exposed nectar, the Apiaceae are the most visited, especially by the social species. In addition, ivy (Hedera helix) is visited abundantly (Fig. 5.5), and both the hornet and the common wasps can be seen on it in October. They spend a lot of time taking nectar, though they may also be attracted by the presence of flies for prey.

Individuals of Vespula and Dolichovespula, when visiting heath and cross-leaved heath (Erica cinerea and E. tetralix), take the nectar through borings, the entrances to the flowers being much too narrow for them to get their heads in (Willis & Burkill, 1895–1908). Such borings may be made by the wasps themselves (Block, 1962) but they are more often made by the shorter-tongued species of bumblebee and, of course, they by-pass the pollination mechanism.

In addition to the flowers already named, Vespidae (and to some extent Eumenidae) visit a range of small, more or less globular flowers that Müller (1883) informally referred to as ‘wasp-flowers’. These are described here and listed in Table 5.3. De Vos (1983) found that, on average, one visit by Dolichovespula sylvestris transferred seven times as many pollen grains to the stigma of Scrophularia nodosa as a bumblebee visit, though the total of visits by honeybees and bumblebees was much greater. The genus Cotoneaster is divided on flower form into two parts, one with dingy red nodding globular wasp-flowers (Fig. 6.58C), and one with upright flowers with spreading, pure white petals that are apparently not visited by wasps. The barberry, gooseberry, alder buckthorn, bilberry and cowberry, listed in Table 5.3, are all mainly visited by bees and have never been classed as ‘wasp-flowers’, but their points of similarity to them suggest that the wasps are attracted by the same means. The fact that pendent flowers discourage visits by short-tongued flies and encourage visits by bees was noted by Willis & Burkill (1895–1908). As some of these flowers are more or less nodding, it appears that wasps share with bees a readiness to cling underneath a flower to get nectar.

Table 5.3 ‘Wasp-flowers’ (favoured by Vespidae) and similar forms.

| Scientific name | English name |

| Berberis spp. | Barberry |

| Ribes uva-crispa | Gooseberry |

| Cotoneaster spp. (in gardens) | Cotoneaster (Fig. 6.59) |

| Frangula alnus | Alder buckthorn |

| Vaccinium myrtillus | Bilberry (Fig. 6.7) |

| Vaccinium vitis-idaea | Cowberry |

| Scrophularia nodosa | Common figwort (Fig. 6.58) |

| Scrophularia aquatica | Water figwort |

| Symphoricarpos rivularis | Snowberry |

| Epipactis helleborine | Common helleborine orchid (Fig. 7.4) |

| Epipactis purpurata | Violet helleborine orchid |

(Brian & Brian, 1952; Chambers, 1949; Müller, 1883; Shaw, 1962; Spooner, 1930; Trelease, 1881; Willis & Burkill, 1895–1908; Yarrow, 1945; PFY)

The ants, classed in the superfamily Formicoidea, form a great group of social insects which often form perennial colonies. They are great lovers of nectar and regularly collect it from flowers. Since the worker-ants are wingless and have to reach the flowers by crawling up the stems, they are very unlikely to cause cross-pollination between different plants, and their method of entry to the flower will in many cases permit them to take the nectar without effecting pollination at all. However, there is a rare category of plants which have become adapted to ant-pollination. Typically these are prostrate or low-growing plants and in any case they have small inconspicuous flowers close to the stem. Different individuals intertwine and plants are self-incompatible. A British example is rupture-wort (Herniaria ciliolata, family Caryophyllaceae), which in Cornwall is pollinated by Lasius niger and Formica fusca (L.C. Frost). A similar but unrelated North American plant, Polygonum cascadense (family Polygonaceae), has been dealt with in detail by Hickman (1974), who listed other examples and set out the abovementioned features of the ant-pollination syndrome, to which is added a hot dry habitat in which ants are abundant (for the syndrome concept, see Chapter 6). The characters of the plant Diamorpha smallii (family Crassulaceae), found to be mainly ant-pollinated by Wyatt (1981), proved to fit this syndrome very well. The plant grows on hot dry granite outcrops in the south-east United States. In the Mediterranean region Paronychia species, identical in habit to Herniaria, belonging to the same family and growing in soil pockets on coastal rocks, receive flower-visits from ants (PFY; see also Fig. 5.6). A few cases of orchid-pollination by ants are known, one of which involves winged male ants in a pseudocopulatory relationship (Peakall, 1989; see here). Further examples of ant pollination are listed by Peakall et al. (1991).

Except on such plants as these, ants are liable to be harmful visitors and the adaptations of plants to exclude them were treated in detail in a little book by Kerner (1878). The two main ways by which plants exclude ants are the formation of impassable barriers between the ground and the flowers, and the provision of additional nectaries away from the flowers to act as decoys. Impassable barriers are found in teasel (Dipsacus) in the form of pools of dew and rainwater around the stem, held by the united bases of each pair of leaves, and in some species of catchfly (Silene) in the form of sticky zones on the upper parts of the stem, though they may have other functions as well. Decoy nectaries (‘extra-floral nectaries’) occur on the stipules at the bases of the leaves of some vetches (Vicia spp.) and near the base of the leaf-blades in the cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus) which is commonly grown in gardens.

In many tropical plants nectar is specially provided outside the flowers to attract ants. The ants, being powerfully equipped for biting and stinging, then protect the plant from various kinds of attack, including nectar-robbery by corolla-piercing. Among the tropical plants which secrete nectar on the leaves, bracts or calyces, are some that are pollinated by the large and powerful Xylocopa bees. Since the floral mechanism makes it difficult to obtain entry to the internal nectar, these bees are often tempted to pierce the corollas from the outside. The ‘ant-guard’, however, effectively deters them from doing so. The flowers seem to be provided with a chemical means of keeping the ants away from the inside of the corolla (van der Pijl, 1954). In Trinidad, the nectar of the tropical weed Hippobroma longiflora, which is consumed by hawkmoths, elicits a strong negative reaction by ants (and is also distasteful to humans) (Feinsinger & Swarm, 1978).

The Hymenoptera dealt with so far are of slight significance as pollinators when compared with the one remaining group of this order, the bees. The different groups of bees are sometimes treated as subfamilies of a single family, the Apidae, or sometimes as separate families (O’Toole & Raw, 1991), which is more convenient for us. Unlike the wasps, they are nearly all complete vegetarians. The adults of both sexes feed on nectar and, sometimes, pollen, and the larvae on both nectar (after its conversion to honey) and pollen. As with true wasps, the larval food is collected by the female adults. Nectar is a solution of one or more of the three sugars, sucrose, glucose and fructose (see Chapter 2). After collection, the nectar is carried in the bee’s crop and any sucrose in it is enzymically converted to glucose and fructose (one molecule of sucrose makes one each of glucose and fructose). The product is honey. The vast importance of the bees as pollinators arises from the fact that the larvae, unlike all other insect larvae, have large quantities of flower-food brought to them or stored up for them in the nest by the female adults. Many flowers are specially adapted to pollination by bees, and many others, less specialised, benefit from their activities.

There are about 240 species of bees in Britain. The bumblebees (Bombus), belonging to family Apidae, have exactly the same life-cycle as the social wasps, with fertilised queens founding colonies in spring, and being later helped by their worker offspring. They number about 20 species. The honeybee (Apis mellifera) is different from all other British social bees and wasps in that the colony remains in being all the year round, and new colonies are founded by queens that are accompanied by part of the worker population of the parent colony. The life-history of the non-social majority is much like that of the non-social wasps but a great many bees appear in March or early April, whereas in Britain very few non-social wasps emerge before about the end of May. Varying levels of social organisation occur in the mainly non-social Halictidae and some species of Halictus and Lasioglossum have a similar system to that of Bombus, but two or three females may combine to start a nest in spring, and the colonies are much smaller. A considerable proportion of bee species are inquilines, laying their eggs in the nests of other species, as described for wasps.

Numbers of honeybees and their distribution in the habitable world are unnatural, being governed by the provision and movement of hives (see Chapter 13). In addition, they have a longer season of activity than any other kind of bee. When left to themselves they nest chiefly in hollow trees and cavities in buildings. Bumblebees also have a rather long season, but their numbers are disproportionately small early in the year; they nest in grass tussocks or underground (usually in ready-made holes) according to species. The non-social bees, together with the social species of Halictus and Lasioglossum, burrow in the ground or make nests in hollow stems, in rotten wood, in beetle holes in wood, in snail shells, in holes and crevices in masonry, or under stones. The situation chosen depends on the kind of bee concerned, and the occurrence of non-social bees is thus somewhat restricted by availability of nesting sites. The ground-nesting species may also be restricted in occurrence by their soil preferences for nesting purposes. The season of activity of many species is short but many genera contain both early and late species, while some species can be seen over almost as long a period as the honeybee, this being achieved by having two or three broods during the year so that there are periods of absence or scarcity between broods (see Box 5.2).

Owing to the bees’ need for pollen, which is usually easily accessible, general compilations of flowers visited by the various species of bees do not show much correlation between the tongue-length of the insect and the accessibility of the nectar (see Knuth, 1906–1909; Westrich, 1990). Kugler (1940) reported, for instance, that species of Lasioglossum readily collect pollen from flowers whose nectar they cannot reach. However, tongue-length (Table 5.4) must limit a bee’s choice of flowers for nectar-gathering except where holes are bitten in the corolla, as they often are by bumblebees, some of which appear to be more resourceful than the solitary species in getting food in unconventional ways. The particular preferences of bees for certain flowers already mentioned often concern flowers that provide both nectar and pollen; most of the family Asteraceae have flowers which provide good supplies of both, and the same applies to many Fabaceae-Faboideae. These two families are particularly suited to the bees with abdominal pollen brushes as, with few exceptions, they present their pollen from below and the bees can scrape it directly into the brush. Sometimes bees will take pollen from some flowers and nectar from others; this is commonly the case with the social species, but it occurs also with solitary bees; for example, Anthophora plumipes visits peonies (Paeonia spp.) in gardens for pollen only (PFY).

Fig. 5.7 Bumblebee, Bombus terrestris (female; Hymenoptera Aculeata: Apoidea), on ramsons (Allium ursinum).

However, it seems that some long-tongued bees never visit certain flowers with rather easily accessible nectar, for there are no records of visits of Megachile or Anthidium to ragwort (Senecio jacobaea) according to Harper & Wood (1957). Even more restricted in their habits are Macropis europaea and Andrena marginata (already mentioned), and Andrena praecox, a very early bee which takes pollen exclusively from sallows (Chambers, 1946). Andrena bicolor visits a great variety of flowers in its first brood, while in certain localities the second brood rarely visits anything but Campanula and Malva, and in some other localities nothing but dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) and bramble (Rubus fruticosus) even when Malva is available. Such situations are rather frequent in Andrena and they are paralleled in their inquilines, Nomada, which may actually specialise in the same flowers as their hosts (Friese, 1923). Bees that visit only one or a few species of flowers for food are described as oligotropic, while those showing a similar restriction for pollen supplies are called oligolectic. Oligolecty appears to be rather rare in British bees but a good example is provided by Melitta (Melittidae); its four species specialise respectively on certain Fabaceae-Faboideae, Onobrychis viciifolia (also in Fabaceae), Campanula rotundifolia (Campanulaceae) and Odontites verna (Scrophulariaceae). However, oligolecty is a common and striking phenomenon in some parts of the world and examples from America are quoted in Chapter 13. In some of these cases, the flowers concerned are the meeting place of the sexes; this is so with the British bee Macropis europaea, in which the females leave a special scent on the Lysimachia flowers which makes these attractive to other females (even when all pollen has been removed) and especially to males (Kullenberg, 1956b). In a particular experiment concerning four species of bumblebee, with varying lengths of tongue, Brian (1957) found that when gathering nectar in competition with each other these species tended to restrict themselves to the flowers most appropriate to their tongue length, although at least the longest-tongued species was not so selective when there was little competition.

Fig. 5.8 Non-social short-tongued bee (Andrena sp., female; Hymenoptera Aculeata: Apoidea), on dandelion (Taraxacum officinale agg.).

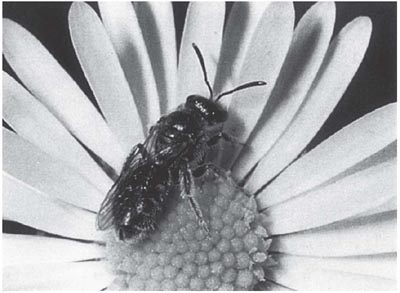

Fig. 5.9 Non-social bee: a small species of Lasioglossum (female), on common daisy (Bellis perennis).

The first bees to appear in spring are honeybees (Fig. 5.16, Fig. 6.47), and these are followed by the first queen bumblebees (Fig. 5.7, Fig. 6.8, Fig. 6.32) and, among the non-social bees, the early andrenas (Andrenidae, Fig. 5.8, Fig. 5.14) and two species of Anthophora (Anthophoridae) (Plate 2d). Honeybees have medium-length tongues and visit practically any available flower. Bumblebees have long tongues but their choice of flowers in early spring is very limited, the chief natural flower for them at this time being sallow catkins (Salix spp.). Andrena is the largest genus of bees in Britain, with over 60 species, all of which nest in the ground. Most of them are very short-tongued. It is the larger species of the genus which emerge first, and these may be as large as or larger than the honeybee. The thorax of these larger species, and sometimes the abdomen also, is densely hairy; the females of some could be mistaken for the honeybee but others are beautifully patterned and coloured. The andrenas active in March and April visit chiefly sallows and the early yellow composites (Asteraceae) (Fig. 9.9a). As the sallows are dioecious, bees collecting pollen only will not cause pollination. The early species of Anthophora (A. relusa and A. plumipes) are rounded furry bees rather like small bumblebees but they frequently hover; the males are mainly brown while the females are entirely black except for their rust-coloured pollen brushes. Their movements are extremely quick and they are more easily frightened by the human presence than the bumblebees. Their tongues are very long and they visit mainly large tubular flowers.

In March or April the first Lasioglossum species appear; these early ones are among the smallest of their genus – tiny blackish bees with rapid oscillating flight (Fig. 5.9). In gardens in April these small bees are often seen round Spanish bluebell (Hyacinthoides hispanica) which has large, bell-shaped flowers which they can crawl right into. The smaller andrenas now emerge and these are similar to the small Lasioglossum though a little larger and with more flattened abdomens. Both these groups of small bees visit yellow composites and birdseye speedwell (Veronica chamaedrys; see here). A common bee in gardens in April is the reddish-brown mason-bee Osmia rufa (Megachilidae, Fig. 5.10), with a furry body about 12 mm long. The pollen brush is on the undersurface of the abdomen instead of on the hind legs as in most bees. It has an extremely long tongue but visits a wide variety of flowers, including the wide open fruit blossom flowers with partly concealed nectar, which also attract the larger andrenas at this time.

In late April and during May further species of Andrena (Plate 2c), Lasioglossum (Fig. 5.12) and Osmia (Fig. 5.10) appear, as well as representatives of some other genera. These include Sphecodes (Halictidae), which are black with a red band on the fore-part of the abdomen, and Nomada (Anthophoridae, Fig. 2.14), which are banded with black and yellow, or brown and yellow, and look like wasps. In both genera the hair clothing is sparse, and both are inquilines, Nomada usually on Andrena, Sphecodes on Halictus and Lasioglossum. The blossoms of hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) are much visited by Andrena, Halictus and Lasioglossum during May.

In the course of June, worker bumblebees become numerous and representatives of most of the remaining genera also appear. Among these are Hylaeus (Colletidae), small shiny black bees, called in Germany ‘mask-bees’ because of their pale yellow facial markings. Hylaeus have few body hairs and no pollen brush (Fig. 5.11); the pollen required for the larvae is carried in the crop with the honey. The proboscis is very short. A wide variety of flowers is visited, but the species are particularly attracted by wild mignonette and weld (Reseda spp.). Colletes (Colletidae) also appear in June; these resemble medium-sized andrenas and the common garden species visits chiefly yarrow (Achillea millefolium), cultivated Achillea species, tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), and related Asteraceae, all with heads of closely-packed short tubular florets (Plate 2b). Friese (1923) noted that species of Colletes restrict themselves to a smaller selection of plants than Hylaeus and Lasioglossum and that their emergence is closely related to the flowering of their favourite plants. Panurgus (Andrenidae) may also appear in June; the two British species are blackish-brown with orange pollen brushes on the hind legs. They nest in sandy soil and are particularly fond of the yellow ligulate-flowered composites. The three remaining genera of Megachilidae, bees that collect pollen on the underside of the abdomen, also appear in June. These are Megachile (the leafcutter-bees), which favour Asteraceae, Campanulaceae and Fabaceae-Faboideae; Chelostoma, which favour Campanulaceae; and Anthidium, of which the only British species, the carder bee (A. manicatum), visits chiefly the large tubular flowers of Scrophulariaceae and Lamiaceae, as well as frequenting Fabaceae-Faboideae. Anthidium is unusual in that the males are larger than the females instead of smaller and hold territories based on plants at which the females forage; they are large brown bees, capable of hovering, with yellow on the face and yellow spots on the abdomen. Other bees that emerge in June are Lasioglossum leucozonium, one of the larger species of the genus, with similar flower-preferences to Panurgus, and Anthophora quadrimaculata, with similar preferences to Anthidium.

In July the species of Colletes that visit ling (Calluna vulgaris) emerge, as well as various species of Andrena found on sandy heaths, some of which favour ling and bell heather (Erica cinerea). The longer-tongued Andrena marginata also emerges in July, when its favourite flowers, scabious (Knautia arvensis, Scabiosa columbaria and Succisa pratensis) and knapweed (Centaurea) are out. Macropis europaea (Melittidae) also emerges in July and visits yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris) almost exclusively for pollen and nutritive oil (Vogel, 1976b, 1986) (see here & here).

Fig. 5.10 Long-tongued solitary bee, Osmia rufa (mason bee, probably a female), sucking nectar from wallflower (Cheiranthus cheiri).

Fig. 5.11 Short-tongued solitary bee (Hylaeus sp.), on wallflower (Cheiranthus cheiri); the bee can reach the pollen but not the nectar.

Fig. 5.12 Non-social bee: a medium-sized species of Lasioglossum foraging for pollen on white clover (Trifolium repens).

Chambers (1945, 1946) noticed that andrenas collect pollen from certain wind-pollinated trees, and honeybees are particularly noted for visits to a variety of wind-pollinated plants, including even a gymnosperm, yew (Taxus baccata) (Hodges, 1952). Wind-pollinated flowers are inconspicuous but they usually produce very large quantities of pollen which, however, is not sticky. This does not seem to make it difficult for Andrena to collect it, although these species do not moisten pollen with honey as do some bees, including the honeybee. Since many wind-pollinated flowers are unisexual the female flowers are not visited by the pollen-collecting insects, which thus fail to pollinate the plants.

Table 5.4 Lengths (in mm) of proboscis and body of some British bees (both sexes, unless otherwise stated).

| Species | Proboscis length (mainly from Knuth, 1906–1909) | Body length |

| Colletes daviesanus | 2.5–3 | 8 |

| Hylaeus communis | 1.25 | 6.5 |

| Halictus rubicundus | 4–4.5 | 10 |

| Lasioglossum morio | 2.5 | 5.5 |

| Lasioglossum leucozonium | 4 | 7–9 |

| Sphecodes reticulatus | 2 | 8.5 |

| Andrena argentata | 2.5 | 8 |

| Andrena bicolor | 2.5 | 7.5–9.5 |

| Andrena marginata | 3.5–4 | 8–9.5 |

| Andrena pubescens | 3.5 | 9.5–13.5 |

| Anthophora plumipes | 13 | 14 |

| Anthophora quadrimaculata | 8 | 9–10.5 |

| Melecta luctuosa | 11 | 14 |

| Nomada goodeniana | 4 | 9–11.5 |

| Megachile centuncularis | 6–7 | 9–11 |

| Coelioxys elongata | 4.5 | 12 |

| Osmia caerulescens | 8 | 6.5–9 |

| Osmia rufa | 7–9 | 9–11 |

| Bombus pascuorum (queen) | 11–14 | 15–17 |

| Bombus pratorum (queen) | 10–12 | 16 |

| Bombus sylvarum (queen) | 14 | 16 |

| Bombus hortorum (queen) | 18–19 | 20 |

| Bombus lapidarius (queen) | 14 | 22 |

| Bombus terrestris (queen) | 10 | 24 |

| Apis mellifera (worker) | 6 | 13 |

The scents of bee-pollinated flowers are sometimes indistinct to us, but those which we can clearly perceive are rather varied. The honeybee and short-tongued bumblebees freely visit many of the flowers visited by Diptera, some of the scents of which are described here. The flowers that are more specially adapted to bees have generally a sweet scent which, even when strong, is more delicate to the human nose than the heavy scents common in Lepidoptera-pollinated flowers (see here), but as with that group, the same scent may be found in many unrelated flowers. For example, the scent of sweet violet (Viola odorata) is like that of Iris reticulata (a commonly cultivated Middle Eastern species which, incidentally, flowers at about the same time as this violet and is similar to it in colour). Very similar to these, but more strongly scented, is the cultivated mignonette, Reseda odorata, from North Africa. Honey-like scents are common in Fabaceae-Faboideae, examples being white clover (Trifolium repens), tree lupin (Lupinus arboreus, a Californian plant introduced into Britain), and spanish broom (Spartium junceum, from the west Mediterranean region). In the last two, the scent is very powerful; both species have pollen flowers, like gorse (Ulex europaeus), which smells of coconut. Other recurring scents of bee-pollinated flowers are the plummy scent of the grape hyacinth (Muscari neglectum) and oxlip (Primula elatior), the disagreeable smell of Helleborus foetidus, and the pleasant scent of the garden pansy (Viola × wittrockiana) which is to be found in species of michaelmas daisy from both Europe and North America (for example, Aster sedifolius and A. puniceus, which are visited mainly by bees and hoverflies) and in some other flowers (PFY).

Many species of bees are involved in the relationship of pseudocopulation with orchids (Ophrys spp.) in the Mediterranean region; the bee genera usually concerned are Andrena (Andrenidae) and Eucera (Anthophoridae) (see here). Males of some Apidae (subfamily Bombinae, tribe Euglossini) are involved in the strange pollination processes of certain tropical American orchids, during which they collect fragrant compounds for later deposition at sites where females may appear (see here). The fragrance is collected by brushes of hairs on the forelegs and then stored in the hind tibiae which are specially enlarged and chambered to take the liquid (Vogel, 1966). These bees also visit members of several other plant families that provide similar fragrances. One such plant is Dalechampia in the Euphorbiaceae. This genus is particularly interesting in that most of its species, instead of supplying fragrances to male euglossine bees, offer resin for building or lining nests to female euglossines (and other bees) (Armbruster & Webster, 1979; Armbruster et al., 1989). In addition, bees specialised to collect oil in place of nectar from certain flowers (as Macropis does from Lysimachia [see here]) occur in various parts of the world, for example Rediviva (Melittidae), which gathers oil by inserting its enlarged forelegs into the twin-spurred flowers of Diascia (family Scrophulariaceae) in southern Africa (Vogel, 1974, 1984; Steiner & Whitehead, 1988). This is a striking case of co-evolution. For transport, the bee adds the oil to its pollen load (see also Vogel, 1990).

These are adapted for both nectar-collecting and nest-building. The tongue ranges in length from shorter than the insect’s head to longer than its body. The bristly glossa is greatly developed compared with that of other Hymenoptera and, except in the shortest-tongued forms, its edges are rolled back so that it looks like a tube with a slit along the back. Most probably this is not a feeding tube, and liquid uptake is by the hairs on its outside. The galeae of the maxillae have evolved to form a sucking tube, though in a very different manner from those of the Lepidoptera (Chapter 4). The mouth-parts of various bees are described in Box 5.3–Box 5.5 (fullest details are available for the honeybee, Box 5.4).

Evolution has undoubtedly progressed in the direction of greater proboscis length, but this process is better thought of as specialisation than as improvement. The gaining of access to deep-seated nectar is accompanied by decreased case of collecting fully-exposed nectar, as observed by Kugler (1943) in bumblebees.

The collection of pollen as food for the larvae is carried out in various ways by different bees. In Hylaeus pollen is carried entirely in the crop mixed with the nectar. Curiously, Hylaeus resembles all other bees in having some of the hairs branched, which is a feature generally regarded as an adaptation to pollen collection.

The abdominal pollen-collectors (Megachilidae) all have the underside of the abdomen thickly clothed with hairs which curve slightly towards the tail. Saunders (1878) found that the pollen brushes in this family consist of different kinds of hairs; thus in mason-bees (Osmia) and leafcutter-bees (Megachile) the hairs (unlike those elsewhere on the body) are unbranched, those of Megachile being spirally grooved, whereas in Chelostoma the hairs are waved and branched. The legs are used to gather up the pollen and transfer it to the abdominal brush. They are adapted to this by bearing bristles which are developed into a stiff brush on the inside of each metatarsus (compare Fig. 5.13A) and into a comb on the inner edge of each of the fore- and mid-tibiae towards their tips. These stiff hairs may be used both to collect pollen from flowers and to groom the body of the insect. While leafcutter-bees are flying from flower to flower their legs hang down and are scraped together, the pollen being passed back to the hind legs. These are then raised and the pollen transferred to the abdominal brush. However, pollen can sometimes be transferred to this brush straight from the flower (see here), with or without the assistance of the hind legs.

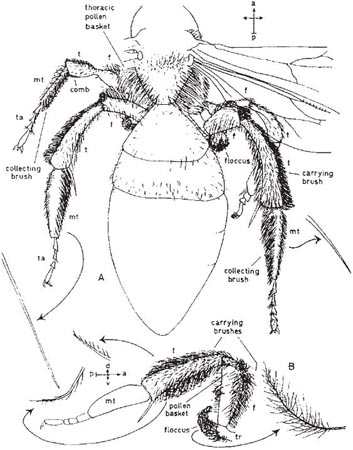

The bees that carry home the pollen on their legs resemble the abdominal collectors in having stiff pollen-gathering hairs on the insides of the metatarsi (present even in Hylaeus but there used only for cleaning the body), but these hairs sometimes extend to other joints of the tarsi. Andrenas carry home the pollen on the main joints of the hind legs and also on parts of the thorax (Fig. 5.13 & Fig. 5.14). The hind tibiae are densely clothed with branched and unbranched hairs, which form a large pollen-carrying brush. On the other hand, the hind femora carry part of their pollen in a brush on the front surface and most of it on the lower surface in a basket-like structure formed by fringes of branched hairs. The trochanter, one of the two small joints between the femur and the body, carries a group of beautiful long plumose hairs which descend and then curve rearwards, constituting the floccus. These hairs themselves enclose pollen and also help to close in the baskets of the femora.

Fig. 5.13 Pollen-collecting apparatus of Andrena denticulata. A, the insect seen from above (front legs, other parts of the body, and certain details omitted); B, right hind leg (coxa and details of tarsus and metatarsus omitted): f, femur; mt, metatarsus; t, tibia; ta, tarsus; tr, trochanter. Length of body parts shown is 11.5 mm. Individual hairs shown at greater magnification. For ‘compass-points’ see Fig. 3.10.

Fig. 5.14 Non-social bee (Andrena sp.), foraging at common melilot (Melilotus officinalis), and carrying a load of pollen.

Like the leafcutter-bees, andrenas commonly carry out pollen-packing when in flight from flower to flower, but sometimes they do it before leaving the flower. In addition, some species make the pollen easier to transport by moistening it with nectar regurgitated from the crop.

The pollen-collecting apparatus in Colletes and Lasioglossum is closely similar to that of Andrena. In both genera, however, the hind femora carry all their pollen in a basket on the underside, and the branched hairs corresponding to the floccus of Andrena arise at the base of the femur. The branches of these hairs diverge widely and overlap to form a mesh; similar hairs clothe much of the thorax of Colletes. Lasioglossum has no thoracic pollen baskets, but it collects some pollen in the dense hairs beneath the front of the abdomen. In both these genera, the curved hairs on the lower side of the hind tibiae show a fan-like development of branches near the tip.

Both Lasioglossum and Colletes pack their pollen before leaving the flower, brushing each foreleg several times very rapidly on the middle leg, and each middle leg on the hind leg. These movements take place only on one side at a time, but both hind legs can be employed simultaneously to clean the under surface of the abdomen.

A simpler system for carrying pollen on the legs is found in Melittidae and Anthophoridae. The hind metatarsus is more enlarged, and this joint and the hind tibia have large brushes of backwardly directed pollen-carrying hairs, usually confined to their outer surfaces. Eucera and Melitta moisten their pollen with nectar. Dasypoda differs in having some pollen-carrying hairs on the hind femur and and a dense brush of very long feathery hairs over the entire surface of the tibia and the large metatarsus, the last-mentioned joint having no stiff combing bristles on the inner surface. On account of its enormous pollen-carrying capacity, Dasypoda is illustrated in almost every book on pollination, though the more complex arrangements in Andrena are more interesting. Panurgus, in the Andrenidae, has a similar distribution of pollen-carrying hairs to Dasypoda, with some branched hairs on the femur, but their capacity is slight compared with those of the tibia, which is unusually well clothed with pollen-carrying hairs on the inner surface. These hairs are waved and pinnate with numerous short branches.1

The glossa is short in the genera Hylaeus (Diagrams A, B) and Colletes (Colletidae) (C, D), Andrena (Andrenidae) (F, G), Halictus (J) and Lasioglossum and also in Sphecodes (all Halictidae). The first two of these are the shortest-tongued of all bees and are peculiar in having the glossa bilobed as in Vespidae. The detailed structure of the glossa and paraglossae in these two genera is adapted to the job of lining the nest with a fluid secretion (Demoll, 1908) but the hair-fringe of the glossa (C) presumably absorbs nectar. By drawing the glossa back into the space above the mentum and beneath the galeae of the maxillae, pressure and suction can probably be applied to it so that nectar imbibed by the hairs can pass into the mouth. Demoll (1908) believed that the nectar first passes through a very narrow passage between the glossa and the paraglossae. In any case, the nectar then travels backwards through a tube formed by the mentum and the overlapping maxillae (Saunders, 1890). These structures are linked towards the base by a membranous bag, the ‘throat-membrane’ (E shows this in transverse section at the level of the mouth [after Demoll, 1908]; the epipharynx is hanging down in front of the mouth). In the upper side of this are two folds which connect the edges of the maxillae to the labrum (H,J) forming a covered passage which links the mouth with the basal ends of the maxillae, so that fluid passing back from here is unable to escape. The folds are probably kept together by tension when suction is taking place, and narrow rods present in their edges may help to keep the gap closed. The underside of the membranous bag continues back under the head where it lines the cavity into which the mouth-parts are retracted when not in use. Embedded in it are the sclerites that join the mouth-parts to the hard parts of the head and project and retract them (H, Box 5.4 Diagram A, and Box 5.5 Diagram E); the cardines move the entire apparatus to and fro while the lorum can move the mentum in relation to the maxillae. In order to project the mouth-parts, the cardines have to swing forwards and downwards and this great movement is made possible by the skin of the throat-membrane loosely linking the hardened joints together. The lowered position of the mouth-parts when nearly fully projected can be seen in B, H and J and their retracted position in Box 5.4 Diagram L.

In Andrena the proboscis is again short and constructed much as in Colletes and Hylaeus, but the galeae are large, horny and opaque, instead of partly translucent. The paraglossae are well-developed and the undivided tip of the glossa forms a sort of scoop (F). Andrena marginata is one of a few species that have a longer proboscis (G,H). All the parts are somewhat elongated in comparison with those of other species and the glossa is more tongue-like, and covered with long hairs towards the tip. In Halictus and Lasioglossum the ratio of the proboscis-length to the body-size is about the same as in Andrena marginata, but the proportions of the parts are different, the stipes (the basal part of the maxilla) being relatively longer (J). The mentum is also longer as it has to match the length of the stipes, while the hairy convex glossa is short. Sphecodes species (mostly inquilines of Halictus and Lasioglossum) have similar but slightly shorter mouth-parts.

A third and final group of bees that collect pollen on their legs consists of the social bees, Apis (Fig. 5.15) and Bombus. In these, the collection of pollen is similar to that of other bees in its first stages but quite different in its final stages.

In the honeybee (Apis mellifera) (Fig. 5.16) pollen is scraped off the head and forepart of the thorax by the antenna-cleaners and combs of the forelegs. The middle legs clear pollen from the hind part of the thorax and the hind legs clear it from the abdomen. All this pollen is worked into the brushes on the inner surface of the metatarsi of the middle legs, and is moistened by regurgitated honey. After this each middle leg in turn is placed between the two hind legs and then drawn forward; this action scrapes the pollen into the metatarsal brushes of the hind legs. When sufficient pollen has accumulated on the hind metatarsi, it is transferred to the pollen baskets (or corbiculae) on the outside of the hind tibiae. This is made possible by a structure known as the pollen press, which is found only in the social Apidae and is, perhaps, the most striking adaptation to pollen collection found among all bees. As can be seen from Fig. 5.16C, D, the hind tibiae and metatarsi are flattened and greatly widened compared with those of the other legs. The metatarsi, however, are attached to the tibiae only at the front by a narrow joint (Fig. 5.16C); this allows the press to be opened by the bending down of the metatarsus and closed by its bending up. The proximal end of the metatarsus is produced (except at the actual joint) into an outwardly directed flange which slightly overlaps the apex of the tibia; this flange is called the auricle (Fig. 5.16E). Two actions are required to transfer pollen from the inner surface of the metatarsus of, say, the right leg to the pollen basket of the left leg. In the first, the rake of spines on the apex of the left tibia is pushed downwards through the hairs of the right metatarsus. This scrapes pollen into the space between the rake and the left auricle.

The separated mouth-parts of Apis (family Apidae) are shown in Diagram A (after Snodgrass, 1956) (for mouth-parts of a long-tongued bee in their natural extended position see Box 5.5). The glossa of Apis is moderately long (A, D). In all bees it is a flexible structure with a springy rod running along it (E); muscles attached at the base of the rod can induce a great deal of movement in it, and there is in addition always a mechanism for drawing the base of the glossa some way back into the gutter-shaped mentum so that the whole is able to move to and fro in the front part of the food channel. The secretion of saliva takes place on the mentum near the attachment of the glossa (J).

At least in the honeybee the mouth-parts also contain the taste organs. As with the bees already described, the stipites of the maxillae, together with the labium, form a food channel (F), while food is licked up by the glossa; however, in the honeybee the galeae of the maxillae and the labial palps are greatly developed, so continuing the food channel forward around the longer glossa (D, E).

The slit along the underside of the glossa is closed by dense fringes of hairs; its surface is transversely ringed and each ring is the seat of a row of stiff hairs (B). The shape and position of the glossa rod is seen in E; towards the base it has the possibility of some movement to and fro within the glossa, and as a result it is able to tighten or slacken the skin of the glossa so that the hairs of the glossa stand up or lie down. When the glossa is fully extended, the hairs spread and can thus absorb liquid between them, and as it is drawn back they close up and release the liquid into the food channel. The glossa rod is apparently able to produce bending movements at the tip of the glossa which assist in licking up nectar. These movements can be seen in wide flowers, such as a small Crocus visited by Anthophora (PFY), or in captive bumblebees drinking from artificial containers (Friese, 1932), when the galeae and palps are seen to be firmly united around the glossa as it moves to and fro, sweeping the fluid into the tube. The proboscis may be extended fully if this is necessary to reach the nectar (Müller, 1883), but when the food has been imbibed among the hairs of the glossa, the proboscis has to be slightly retracted; this brings the raised part on the base of each maxilla back into contact with the lobes on the underside of the labrum. The parts fit neatly together and close over the food channel right back to the mouth, just as the throat membrane does in Halictus, etc. (G).

So far we have seen that the food channel lies between two concentric tubes in its distal part (E, section corresponding to a–a of D) and in a tube formed by the maxillae overarching the mentum in its proximal part (F, section corresponding to b–b of A). Another part of the system is formed by the large flattened paraglossae, which ensheath the apex of the mentum and the base of the glossa (H, corresponding to G but with maxillae removed); their shape is such that the saliva, produced from the salivary pouch near the tip of the upper surface of the mentum (J, corresponding to H but with the paraglossae and labial palps removed), is carried downwards on either side and passes into the tube formed by the glossa, entering through an opening on the underside (J, K). The saliva emerges at the extreme tip of the glossa where there is a little flattened disc called the labellum (C, D). The folded mouth-parts of the honeybee are shown in L.

The second movement is a bending upwards of the metatarsus which closes the gap between the auricle and the rake (Fig. 5.16E). The pollen is thereby forced upwards and outwards into the pollen basket (Fig. 5.16F) as a compact and sticky mass. Pressure applied by the springy auricle and its bristles causes successive masses of pollen to be plastered one upon the other. A solitary bristle is present on the surface of the tibia which forms a pin through the pollen mass and is apparently important in holding it in position. The tarsi of the middle legs shape the pollen mass, which is eventually kidney-shaped. The efficiency of the pollen press is probably greatly dependent on the moistening of the pollen, which also makes it possible for the rather sparse unbranched hairs of the pollen basket to carry a large quantity of compacted pollen. Honeybees which collect pollen accidentally when concentrating on nectar-gathering (Fig. 5.17) sometimes retain it but may discard it. In discarding pollen, they make movements similar to those made when packing pollen, but the position of the legs is different and probably the press is kept closed, so that the pollen just drops away from the rake. Both processes are normally carried out while the insect is in flight. The pollen-packing apparatus of the bumblebee (Bombus) differs in small details.1

Other families in which a long proboscis is found are Andrenidae, Melittidae, Anthophoridae and Megachilidae. In some of these bees the mouth-parts are of a slightly more primitive kind than in the honeybee. In Panurgus (Andrenidae), for example, the glossa is only moderately long and the labial palps are very slender, apparently playing no part in the formation of the food channel, while the maxillary palps resemble those of the bees with a short glossa (Diagram A; after Saunders, 1890). The galeae are long and strongly tapered, so they appear well-adapted to sucking the slender tubular florets of Asteraceae, which are the favourite flowers of Panurgus. Similar mouth-parts are found in Dasypoda and Melitta (Melittidae), the latter having a specialised arrangement of long curved hairs at the tip of the glossa, making it look rather like a bottle brush. A closer resemblance to the honeybee is found in the mouth-parts of Nomada and especially Epeolus (Anthophoridae), two genera of inquilines.

In Anthophora the tongue is much longer than in the honeybee, and the proportions are rather different (B). When the galeae are folded back out of use, they project well back under the thorax of the bee. In Anthophora and the closely similar Eucera the hairs of the glossa have oar-like flattenings which increase their surface area for absorption (C). The bumblebees (Bombus) are rather similar in their mouth-parts to the bees just described.

The remaining bees (Megachilidae) all have rather similar mouth-parts (D, showing Osmia coerulescens, a bee 8 mm long, with tongue extended to 6.5 mm). The glossa is long and is sheathed by the galeae for a greater proportion of its length than in other bees with a long proboscis (Demoll, 1908). The labrum is very large and curved down at the sides, and the galeae are slightly curved. This group consists of the bees which carry pollen on the underside of the abdomen (see here) and the related inquilines, Stelis and Coelioxys. Demoll suggested that the extensive sheathing of the glossa in these bees fits them to feeding from the flowers of Fabaceae-Faboideae, in which the opening is so small that it might squeeze nectar from an unprotected glossa on withdrawal from the flower.

Fig. 5.15 Honeybee foraging for pollen on flower of white rockrose (Helianthemum apenninum). A mass of pollen can be seen in the pollen basket on the hind leg of the bee.

Fig. 5.16 Pollen-collecting apparatus of the honeybee. A, left fore-leg, front view; B, right mid-leg, back view; C, right hind leg, turned forward, back view; D, both hind legs, back view (tibial rake of left leg is about to be pushed through metatarsal brush of right leg); E, two views of left pollen press, similar to those seen in ‘D’ (hairs of pollen basket omitted in left-hand drawing); F, loaded pollen-basket. c, coxa; f, femur; mt, metatarsus; t, tibia; ta, tarsus; tr, trochanter. For ‘compass-points’ see Fig. 3.10. A–C, E after Snodgrass (1956), D, F after Hodges (1952).

Fig. 5.17 Honeybee (Apis mellifera), foraging tor nectar on garden sage (Salvia officinalis). The empty pollen basket shows as a clear shining area, fringed with bristles, on the bee’s hind leg.

Fig. 5.18 Bumblebee (Bombus lucorum worker) buzz-foraging for pollen on bittersweet (Solanum dulcamara).

Bumblebees, but not honeybees, are among the wide range of bees that practise vibratory pollen-collection from certain flowers with dry pollen (see here). The vibration comes from activity in the indirect flight muscles, the main function of which is to cause deformations of the thorax that impart movement to the wings in flight. For pollen-collection, however (as also when warming-up [see here], and for communication by sound-production [see here]), the wings are uncoupled from the flight mechanism so that they vibrate at low amplitude. This sets up a resonance either in the individual anthers or in a space that they enclose, energising the pollen grains, which stream out of the flower. The flowers are usually pendent (Fig. 5.18) and it would seem that the greatest proportion of the ejected pollen will reach the insect in this case. As a rule, these flowers give pollen as the only reward, but a few also give nectar or oil (see here and here). The pollen-carrying brushes of the bees are dense, with interstices that match the rather small size of the pollen grains (see here). This process, often (inaccurately) called buzz-pollination, was reviewed by Buchmann (1983) and discussed by Corbet, Chapman & Saville (1988).

Studies of the senses and behaviour of Hymenoptera that are relevant to pollination have mostly been carried out on social species, and it is mainly these that are covered here. Progress in research on the senses of social bees can be traced in books by von Frisch (1993), Ribbands (1953), Butler (1954), Lindauer (1961), Barth (1982, 1985), O’Toole & Raw (1991), Goodman & Fisher (1991) and many others.

The use by social wasps of their sense of smell in finding food is common knowledge. Verlaine’s (1932a) experiments with scented sugar-water showed that certain scents (heliotrope, violet, jasmine, bergamot and aniseed) attracted wasps while others (cinnamon, lily-of-the-valley, creosote and turpentine) repelled them. A constancy to a particular scent was observed when a choice of attractive scents was offered, and this persisted when the strength of the preferred scent was greatly reduced. This behaviour is similar to that of Diptera and Lepidoptera, described in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4.

Verlaine (1932b) found that when workers have discovered a good food source, they display some excitement on returning to the nest and that when they leave again other workers follow them and may be led to the food directly; others also appear to be alerted and, though not able to follow the direct route to the food, they begin to search for it, probably knowing its scent from encountering it in the nest. An experiment was carried out with unscented sugar-water 25 m from the nest. A wasp that was deliberately introduced to the liquid returned once to four times every ten minutes throughout the day, but no other wasp from the nest came to this food, presumably because it was unscented and rather far from the nest. Communication between wasps relating to food sources is thus of a rudimentary nature.

An investigation of the red-blindness of Vespula rufa was carried out by Schremmer (1941b), who found a wasps’ nest with a conveniently situated entrance – a knot-hole 2 cm in diameter in the side of a white-painted hut. He screened the hole with a white card, so that the wasps could emerge but, on returning, could not see the black entrance hole to the nest. Discs of various colours and 2 cm in diameter were placed on the surface of the hut near the nest hole, and the behaviour of the returning wasps was observed. The wasps mistook the red and purple discs for their black hole; yellow, green and blue discs were ignored, however, evidently being distinguished from black. These results showed that to these wasps red appears as black. Similar methods have been used for some of the Sphecidae, and red-blindness has been found to occur among them also (Molitor, 1937). Spectral sensitivity curves for Vespula vulgaris, V. germanica and a sawfly have been published by Menzel (1990). The first two are red-blind, and the third red-sensitive but blind to ultra-violet.

The olfactory organs of bees are similar to those of other insects and are on the antennae, where they are mixed with tactile hairs. In the worker honeybee, the organs of smell are absent from the first four joints of each antenna and present in the remaining eight. These bees can detect concentrations of scents ten to 100 times weaker than those just perceptible to man, and they are also very good at discriminating between slightly different mixtures of scents (Ribbands, 1955). It was found by Lex (1954) that the different parts of a flower often smell differently to human beings. She then used flowers cut up into these parts for experiments with bees and found that the honeybee could easily distinguish between the scents of the parts. The presence of the organs of smell in the mobile antennae enables bees to explore the exact distribution of the smell of an object. They could thus easily, use the scented guide-marks of a flower, which often coincide with the visible guide-marks, to assist them in finding the nectar. Bolwig (1954), however, found that honeybees did not follow linear scent traces made on coloured models, although coloured objects with scent at one end only were visited chiefly at the scented end.

The role of scent in the approach of honeybees to food was investigated by von Frisch (1954), who trained bees to feed from a blue cardboard box containing jasmine scent, two similar but empty and uncoloured boxes being presented at the same time. The bees were then shown one plain empty box, one plain jasmine-scented box and one blue empty box. They approached the blue box directly from a distance, but on reaching the entrance hole they appeared startled and roamed around outside instead of going in. If they chanced to come within a few inches of the jasmine-scented hole they went in there. Observations show again and again that, just as with Diptera, vision is important in guiding the insects to a food source from a distance, but that scent is taken account of at close range and exerts a powerful influence on their behaviour. Kugler (1940) found that Lasioglossum could distinguish accurately between flower-heads of rough hawksbeard (Crepis biennis) and greater hawkbit (Leontodon hispidus), although they are very similar visually; discrimination took place only at very short range and was doubtless dependent on scent.

It was found by Butler (1951) that honeybee scouts (see here) were attracted to dishes of sugar-water scented with extracts of hawthorn (Crataegus) or white clover (Trifolium repens), but the bees were hardly attracted at all if the dishes were unscented or if they were scented with Spiraea arguta. The experiments were done before these plants had come into flower so that the young bees could not be familiar with the scents, and their reactions were presumably inborn. However, in experiments carried out by Free (1970a), bees trained to yellow and a particular scent, and therefore experienced bees, made more visits to scentless models than to models with a strange scent. This is the reverse of a result obtained with the fly Lucilia by Kugler (see here).

Bees, like flies, can be prevented from visiting a flower if an unaccustomed scent is present. For example, both bumblebees and honeybees, when trained to visit rosescented artificial flowers, refused to alight on models scented with a mixture of rose and lavender, although they approached them closely (Manning, 1957). Similar examples are given for bumblebees by Oettli (1972) and Manning (1956b). Even placing strongly smelling oil-of-thyme among three types of flower that honeybees had been visiting was enough to put a stop to foraging (Butler, 1951). Some solitary bees (Halictus or Lasioglossum) observed by Kugler (1940) made their first approaches to flowers visually and were put off from alighting on field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) by the application of clove-oil to the flowers.

The majority of flowers visited by bees do not have a very strong scent, and in fact the scents to which the bees pay attention at short range may be very faint to our noses. The houndstongue flowers used by Manning and some of the flowers which Lex found to have internal scent differences are not normally thought of as being fragrant. The use of such faint scents by bumblebees was clearly demonstrated by Kugler (1932a,b). The method was first tested using the strongly scented sweet pea (Lathyrus odoratus). Then three types of weakly scented flower (Lycium halimifolium, Echium vulgare, Linaria vulgaris) were tested in separate experiments. The result was that all visits to real flowers were accompanied by proboscis reactions; visually very imperfect unscented models received few visits and no proboscis reactions; similar but scented models received an intermediate number of visits, accompanied by proboscis reactions in some cases. Kugler showed in further experiments that the bees were responding to the specific flower scents, and not merely to the smell of vegetable matter or flower scent in general.

Among the louseworts (Pedicularis spp.) of North America, two species with little or no scent to humans have been shown, even when concealed, to be attractive to their bumblebee pollinators. Although the petal colours could not be seen, the bees unerringly alighted on that portion of the small muslin cage closest to freshly matured flowers. Moreover, individual bees went only to the cages containing the species they had been visiting previously, showing that they could distinguish the louseworts entirely by their smell. A third species of lousewort was found to have a much a stronger scent, and it was suggested that this was related to its shady habitat, in which scent might be more important than in the open (Sprague, 1962).

In locating a food source by scent, insects turn into the wind, and can recognise small increases in intensity, so that they reach its neighbourhood. Near the scent source bees can perceive differences in the intensity of stimulation received by each antenna and they then orientate themselves so as to equalise the stimuli. A bee deprived of one antenna waves the other from side to side to test for the same inequality (Barth, 1982, 1985).

Among honeybees, scent plays an important part in the communication of information about sources of food. Returning foragers bring into the hive the scent of the flowers from which food has been obtained, and this scent is used by other bees to find the same kind of flower. Von Frisch (1950) demonstrated this in the following way: a bowl of fragrant cyclamen flowers was put out near the hive, the flowers having been filled with sugar-water. Not far off, another bowl of cyclamen flowers was put out side by side with one containing phlox flowers which are also fragrant, but none of these flowers had food added. Some bees, presumably alerted by the finders of the original bowl of cyclamen, found the other two bowls, whereupon they ignored the phlox and persevered in searching for food in the cyclamen flowers. If the original cyclamens were replaced by phlox flowers containing sugar-water, bees interested in phlox began to appear at the site of the other two bowls of flowers. Von Frisch also discovered that when a rich source of food lacking scent is found the alerted bees visit scentless flowers. Furthermore, he found that the bees in the hive could learn a flower-scent either from another bee’s body or from the nectar she had collected, which is normally passed round among the bees in the hive. Sometimes, however, the scent on the body is lost during the flight back to the hive, so that the second method is the more reliable. Honeybees are also able to produce a scent themselves, and they sometimes use this when they are on a good food source to attract other bees in the neighbourhood towards them.