Content Area: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: 450–1050

| Merovingian Art | 481–714 | France |

| Hiberno-Saxon Art | 6th–8th centuries | British Isles |

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Lindisfarne Gospels)

Essential Knowledge:

■Early Medieval art is a part of the medieval artistic tradition.

■In the Early Medieval period, royal courts emphasized the study of theology, music, and writing.

■Early Medieval art avoids naturalism and emphasizes stylistic variety. Text is often incorporated into Early Medieval artworks.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Saint Luke portrait page from the Lindisfarne Gospels)

Essential Knowledge:

■There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Middle Ages.

■There is a great influence of Roman art on Early Medieval art.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Merovingian looped fibulae)

Essential Knowledge:

■Works of art were often displayed in religious or court settings.

■Surviving architecture is mostly religious.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Cross-carpet page from The Lindisfarne Gospels)

Essential Knowledge:

■The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

■Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In the year 600, almost everything that was known was old. The great technological breakthroughs of the Romans were either lost to history or beyond the capabilities of the migratory people of the seventh century. This was the age of mass migrations sweeping across Europe, an age epitomized by the fifth-century king, Attila the Hun, whose hordes were famous for despoiling all before them.

Certainly Attila was not alone. The Vikings from Scandinavia, in their speedy boats, flew across the North Sea and invaded the British Isles and colonized parts of France.

Other groups, like the notorious Vandals, did much to destroy the remains of Roman civilization. So desperate was this era that historians named it the “Dark Ages,” a term that more reflects our knowledge of the times than the times themselves.

However, stability in Europe was reached at the end of the eighth century when a group of Frankish kings, most notably Charlemagne, built an impressive empire whose capital was centered in Aachen, Germany.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Monasteries were the principal centers of learning in an age when even the emperor, Charlemagne, could read, but not write more than his name. Therefore, artists who could both write and draw were particularly honored for the creation of manuscripts.

The modern idea that artists should be original and say something fresh or new in each work is a notion that was largely unknown in the Middle Ages. Scribes copied great works of ancient literature, like the Bible or medical treatises; they did not record contemporary literature or folk tales. Scribes were expected to maintain the wording of the original, while illustrators painted important scenes, keeping one eye on traditional approaches, and another on his or her own creative powers. Therefore, the text of a manuscript is generally an exact copy of a continuously recopied book; the illustrations allow the artist some freedom of expression.

EARLY MEDIEVAL ART

One of the great glories of medieval art is the decoration of manuscript books, called codices, which were improvements over ancient scrolls both for ease of use and durability. A codex was made of resilient antelope or calf hide, called vellum, or sheep or goat hide, called parchment. These hides were more durable than the friable papyrus used in making ancient scrolls. Hides were cut into sheets and soaked in lime in order to free them from oil and hair. The skin was then dried and perhaps chalk was added to whiten the surface. Artisans then prepared the skins by scraping them down to an even thickness with a sharp knife; each page had to be rubbed smooth to remove impurities. The hides were then folded to form small booklets of eight pages. Parchment was so valued as a writing surface that it continued to be used for manuscripts even after paper became standard.

The backbone of the hide was arranged so that the spine of the animal ran across the page horizontally. This minimized movement when the hide dried and tried to return to the shape of the animal, perhaps causing the paint to flake.

Illuminations were painted mostly by monks or nuns who wrote in rooms called scriptoria, or writing places, that had no heat or light, to prevent fires. Vows of silence were maintained to limit mistakes. A team often worked on one book; scribes copied the text and illustrators drew capital letters as painters illustrated scenes from the Bible. Eventually, the booklets were sewn together to create a manuscript.

Manuscript books had a sacred quality. This was the word of God, and had to be treated with appropriate deference. The books were covered with bindings of wood or leather, and gold leaf was lavished on the surfaces. Finally, precious gems were inset on the cover.

A spectacular hoard of medieval gold and silverwork was discovered on a farm in Shropshire, England, in 2009. This find is so large that it has forced scholars to reconsider everything that is known about the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of medieval Britain.

Objects are done in the cloisonné technique, with horror vacui designs featuring animal style decoration. Interlace patternings are common. Images enjoy an elaborate symmetry, with animals alternating with geometric designs. Most of the objects that survive are portable.

MEROVINGIAN ART

The Merovingians were a dynasty of Frankish kings who, according to tradition, descended from Merovech, chief of the Salian Franks. Power was solidified under Clovis (reigned 481–511) who ruled what is today France and southwestern Germany. The Frankish custom of dividing property among sons when a father died led to instability because Clovis’s four male descendants fought over their patrimony. With the constant division of land after a king’s death, Merovingian history became marked by internal struggles and civil wars.

Even so, court life and art production could be quite splendid. Merovingian rulers treated their kingdom as private property and exploited its wealth as much as possible, spending lavishly on themselves.

Royal burials supply almost all our knowledge of Merovingian art. A wide range of metal objects were interred with the dead, including personal jewelry items like brooches, discs, pins, earrings, and bracelets. Garment clasps, called fibulae, were particular specialties. They were often inlaid with hard stones, like garnets, and were made using chasing and cloisonné techniques.

Merovingian looped fibulae, early medieval Europe, mid-6th century, silver gilt worked in filigree with semiprecious stones, inlays of garnets and other stones, Musee d’Archeologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France (Figure 10.1)

Form

■Zoomorphic elements: fish and bird, possibly Christian or pagan symbols.

■Highly abstracted forms derived from the classical tradition.

Figure 10.1: Merovingian looped fibulae, early medieval Europe, mid-6th century, silver gilt worked in filigree with semiprecious stones, inlays of garnets and other stones, Musee d’Archeologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Function

■Fibula: a pin or brooch used to fasten garments; showed the prestige of the wearer.

■Small portable objects.

Technique

■Cloisonné and chasing techniques.

Context

■Found in a grave.

■Probably made for a woman.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 53

Web Source https://art.thewalters.org/detail/11727/bow-fibula/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Zoomorphic Elements

–Beaker with ibex motifs (Figure 1.10)

–Buk (mask) (Figure 28.9)

–Aka elephant mask (Figure 27.12)

HIBERNO SAXON ART

Hiberno Saxon art refers to the art of the British Isles in the Early Medieval period; Hibernia is the ancient name for Ireland. The main artistic expression is illuminated manuscripts, of which a particularly rich collection still survives.

Hiberno Saxon art relies on complicated interlace patterns in a frenzy of horror vacui. The borders of these pages harbor animals in stylized combat patterns, sometimes called the animal style. Each section of the illustrated text opens with huge initials that are rich fields for ornamentation. The Irish artists who worked on these books had an exceptional handling of color and form, featuring a brilliant transference of polychrome techniques to manuscripts.

Lindisfarne Gospels, early medieval Europe, c. 700, illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum, British Library, London (Figures 10.2a, 10.2b, and 10.2c)

Function

■The first four books of the New Testament, used for services and private devotion.

Figure 10.2a: Cross-carpet page from the Book of Matthew from The Book of Lindisfarne, early medieval Europe, c. 700, illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum, British Library, London

Materials

■Manuscript made from 130 calfskins.

Content

■Evangelist portraits come first, followed by a carpet page (so called because it resembles a carpet). These pages are followed by the opening of the gospel with a large series of capital letters.

Context

■Written by Eadrith, bishop of Lindisfarne.

■Unusual in that it is the work of an individual artist and not a team of scribes.

■Written in Latin with annotations in English between the lines; some Greek letters.

–Latin script is called half-uncial.

–English added around 970; it is the oldest surviving manuscript of the Bible in English.

–English script called Anglo-Saxon miniscule.

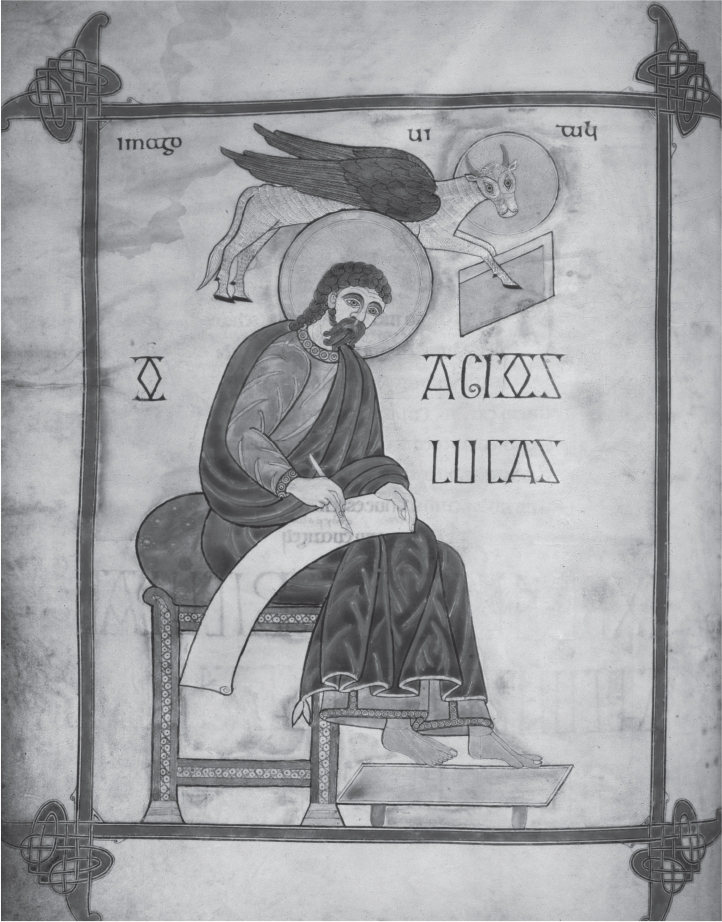

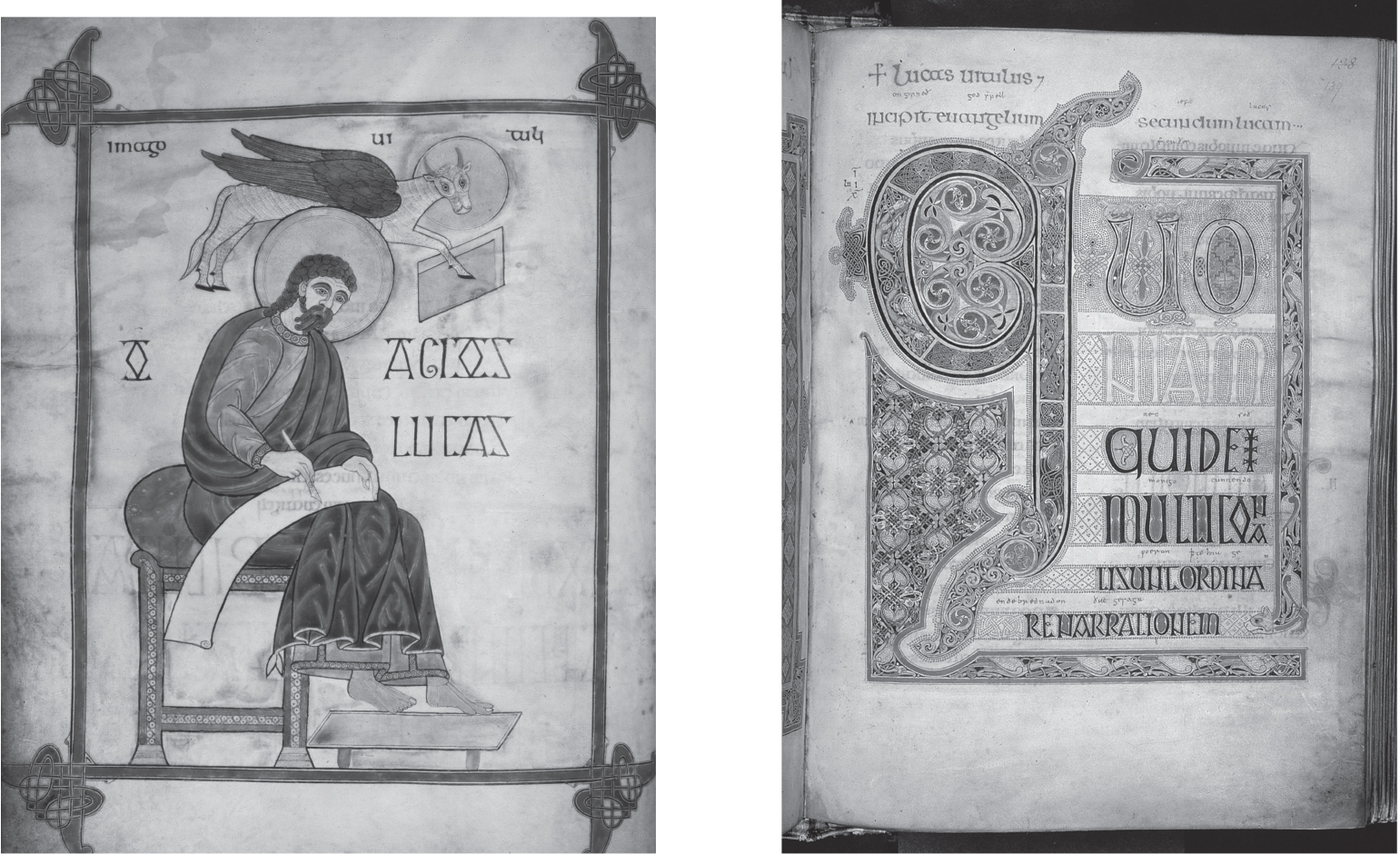

Figure 10.2b: Saint Luke portrait page from Lindisfarne Gospels, early medieval Europe, c. 700, illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum, British Library, London

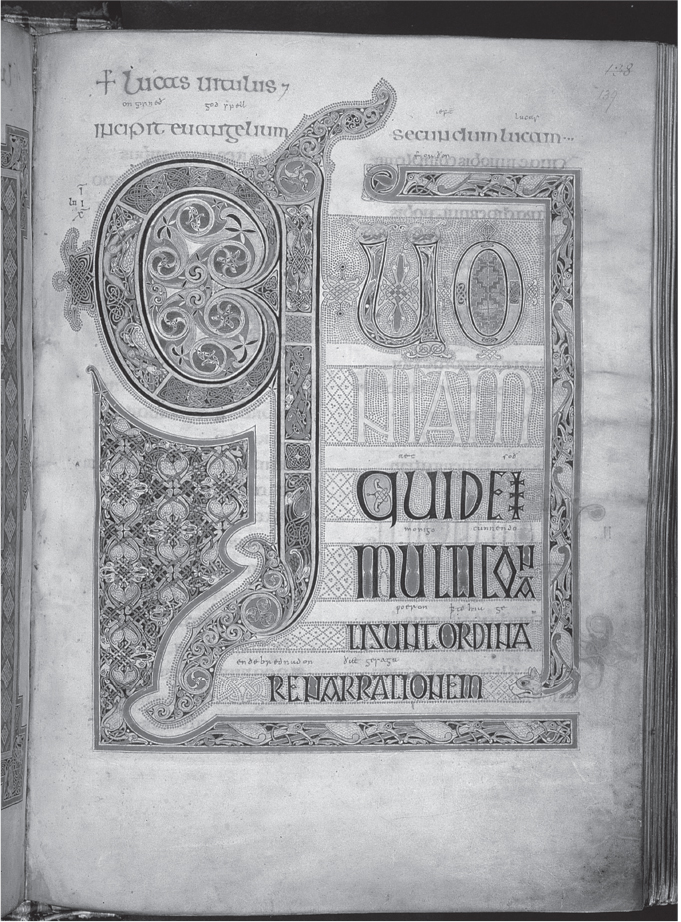

Figure 10.2c: Saint Luke incipit page from Lindisfarne Gospels, early medieval Europe, c. 700, illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum, British Library, London

■Uses Saint Jerome’s translation of the Bible, called the Vulgate.

■Colophon at end of the book discusses the making of the manuscript.

■Made and used at the Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island, a major religious center that housed the remains of Saint Cuthbert.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 55

Web Source http://www.bl.uk/turning-the-pages/

Cross-carpet page from the Book of Matthew from The Book of Lindisfarne

Form

■Cross depicted on a page with horror vacui decoration.

■Dog-headed snakes intermix with birds with long beaks.

■Cloisonné style reflected in the bodies of the birds.

■Elongated figures lost in a maze of S shapes.

■Symmetrical arrangement.

■Black background makes patterning stand out.

Context

■Mixture of traditional Celtic imagery and Christian theology.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 55

Saint Luke portrait page from The Book of Lindisfarne

Context

■The traditional symbol associated with Saint Luke is the calf (a sacrificial animal).

■Identity of the calf is acknowledged in the Latin phrase “imago vituli.”

■Saint Luke is identified by Greek words using Latin characters: “Hagios Lucas.” There is also Greek text.

■Saint Luke is heavily bearded, which gives weight to his authority as an author, but he appears as a younger man.

■Saint Luke sits with legs crossed holding a scroll and a writing instrument.

■Influenced by classical author portraits.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 55

Saint Luke incipit page from The Book of Lindisfarne

Content

■This page is called “Incipit,” meaning it depicts the opening words of Saint Luke’s gospel: “Quoniam Quidem…”

■Numerous Celtic spiral ornaments are painted in the large Q; step patterns appear in the enlarged O.

■Naturalistic detail of a cat in the lower right corner; it has eaten eight birds.

■Incomplete manuscript page; some lettering not filled in.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 55

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Manuscripts

–Golden Haggadah (Figures 12.10a, 12.10b, 12.10c)

–Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Figure 9.8)

–Folio from the Qur’an (Figure 9.5)

VOCABULARY

Animal style: a medieval art form in which animals are depicted in a stylized and often complicated pattern, usually seen fighting with one another (Figure 10.2a)

Chasing: to ornament metal by indenting into a surface with a hammer (Figure 10.1)

Cloissonné: enamelwork in which colored areas are separated by thin bands of metal, usually gold or bronze (Figure 10.1)

Codex (plural: codices): a manuscript book (Figure 10.2a)

Colophon: 1) a commentary on the end panel of a Chinese scroll, 2) an inscription at the end of a manuscript containing relevant information on its publication

Fibula (plural: fibulae): a clasp used to fasten garments (Figure 10.1)

Gospels: the first four books of the New Testament that chronicle the life of Jesus Christ (Figure 10.2b)

Horror vacui: (Latin, meaning “fear of empty spaces”) a type of artwork in which the entire surface is filled with objects, people, designs, and ornaments in a crowded, sometimes congested way (Figure 10.2a)

Illuminated manuscript: a manuscript that is hand decorated with painted initials, marginal illustrations, and larger images that add a pictorial element to the written text (Figures 10.2a,10.2b, and 10.2c)

Parchment: a writing surface made from animal skins; particularly fine parchment made of calf skin is called vellum (Figures 10.2a, 10.2b, and 10.2c)

Scriptorium (plural: scriptoria): a place in a monastery where monks wrote manuscripts

Zoomorphic: having elements of animal shapes

SUMMARY

The political chaos resulting from the Fall of Rome set in motion a period of migrations. The unifying force in Europe was Christianity, whose adherents established powerful centers of learning, particularly in places like Ireland.

Artists concentrated on portable objects that intermixed the animal style of Germanic art with horror vacui and strong interlacing patterns.

Fibulae and other personal jewelry became a sign of status and wealth.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.The Lindisfarne Gospels shows classical influence in its

(A)animals depicted in margins

(B)figures shown in contrapposto

(C)use of Latin

(D)interlace patterning with interweaving forms

2.A fibula can be seen worn in which of the following images?

(A)Sarcophagus of the Spouses

(B)Augustus of Prima Porta

(C)Justinian from San Vitale

(D)Head of a Roman patrician

3.The Merovingian looped fibula shows horror vacui, cloisonné, and chasing techniques common in which of the following traditions?

(A)Roman

(B)Byzantine

(C)Greek

(D)Celtic

4.Zoomorphic designs, as seen in the Lindisfarne Gospels, are similar to those found on

(A)Camelid sacrum in the shape of a canine

(B)Anthropomorphic stele

(C)Jade cong from Liangzhu, China

(D)Tlatilco female figure

5.Gospel books

(A)are biographies of Jesus

(B)foretell the coming of Jesus

(C)discuss apocalyptic visions of the Last Judgment

(D)are letters written by saints after the death of Jesus

Short Essay

Practice Question 4: Contextual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

These are two pages from the Lindisfarne Gospels.

What was the original historical or religious context for this work? Describe at least two contextual elements.

Describe how the original context influenced the choice of both the materials and the imagery in this work.

What aspects of this work show an understanding of cross-cultural connections?

ANSWER KEY

1.C

2.C

3.D

4.C

5.A

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(C) Both (A) and (D) are Celtic inspirations in The Book of Lindisfarne. Choice (B) would be correct except that there is no trace of contrapposto in the drawing of this book. The book is written in Latin, a classical language.

2.(C) Justinian wears a fibula in the Byzantine mosaics in San Vitale.

3.(D) Merovingian looped fibulae show a decline in the classical tradition in Western Europe. Byzantine, Greek, and Roman art are aspects of the classical tradition. Celtic art from Northern Europe developed separately and is from a different tradition.

4.(C) Zoomorphic designs, those having elements of animal shapes, are seen in the jade cong from Liangzhu, China.

5.(A) The four gospels books are, among other things, biographies of the life of Jesus.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

What was the original historical or religious context for this work? Describe at least two contextual elements. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■This gospel book was used for private devotion or for public services. ■Made and used at the Lindisfarne Priory on the Holy Island, a major religious community that housed the shrine of Saint Cuthbert. ■Written by Eadrith, bishop of Lindisfarne; unusual in that it was done by an individual rather than a workshop. |

Describe how the original context influenced the choice of both the materials and the imagery in this work. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■Materials (gold on vellum) indicate a sumptuously illustrated book. ■Materials reflect the sacredness of the subject and the reverence in which it is held. ■Imagery includes Saint Luke as bearded (indicating his philosophical status as a great thinker). ■The traditional sacrificial animal, the calf, hovers over Saint Luke as his symbol. ■Luke appears as an author in the midst of writing on a scroll; the calf holds a completed book. |

What aspects of this work show an understanding of cross-cultural connections? |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Latin writing. ■Classical author portraits. ■Margins written in English. ■Interlace patterning of Celtic origin. ■Greek words written in Latin characters. |