Content Area: Global Prehistory, 30,000–500 B.C.E.

TIME PERIOD

Paleolithic Art 30,000–8000 B.C.E. in the Near East; later in the rest of the world

Neolithic Art 8000–3000 B.C.E. in the Near East; later in the rest of the world

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Stonehenge)

Essential Knowledge:

■Prehistoric art existed before writing.

■Prehistoric art has been affected by climate change.

■Prehistoric art can be seen in practical and ritual objects.

■Prehistoric art shows an awareness of everything from cosmic phenomena (astronomy and solstices) to the commonplace (materials such as clay and stone).

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by locally available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Jade cong)

Essential Knowledge:

■The oldest objects are African or Asian.

■The first art forms appear as rock paintings, geometric patterns, human and animal motifs, and architectural monuments.

■Ceramics are first produced in Asia.

■The people of the Pacific are migrants from Asia, who bring ceramic-making techniques with them.

■European cave paintings and megalithic monuments indicate a strong tradition of rituals.

■Early American objects use natural materials, like bone or clay, to create ritual objects.

■Similarities with Asian shamanic religious practices can be found in ritual ancient American objects.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Running horned woman)

Essential Knowledge:

■Scientific dating of objects has shed light on the use of prehistoric objects.

■Archaeology increases our understanding of prehistoric art.

■Basic art historical methods can be used to understand prehistoric art, but our knowledge increases with findings made in other fields.

PREHISTORIC BACKGROUND

Although prehistoric people did not read and write, it is a mistake to think of them as primitive, ignorant, or even nontechnological. Some of their accomplishments, like Stonehenge, continue to amaze us forty centuries later.

Archaeologists divide the prehistoric era into periods, of which the two most relevant to the study of art history are Paleolithic (the Old Stone Age) and Neolithic (the New Stone Age). These categories roughly correspond to methods of gathering food: In the Paleolithic period people were hunter-gatherers; those in the Neolithic period cultivated the earth and raised livestock. Neolithic people lived in organized settlements, divided labor into occupations, and constructed the first homes.

People created before they had the ability to write, cipher math, raise crops, domesticate animals, invent the wheel, or use metal. They painted before they had anything that could be called clothes or lived in anything that resembled a house. The need to create is among the strongest of human impulses.

Unfortunately, it is not known why these early people painted or sculpted. Since no written records survive, all attempts to explain prehistoric motivations are founded on speculation. From the first, however, art seems to have a function. These works do not merely decorate or amuse, they are designed with a purpose in mind.

Prehistoric Sculpture

Most prehistoric sculpture is portable; indeed, some are very small. Images of humans, particularly female, have enlarged sexual organs and diminutive feet and arms. Carvings on cave walls make use of the natural modulations in the wall surface to enhance the image. More rarely, sculptures are built from clay and lean upon slanted surfaces. Some sculptures are made from found objects such as bones, some from natural material such as sandstone, and some carved with other stones. Early forms of human-made materials, such as ceramics, are also common.

Camelid sacrum in the shape of a canine, from Tequixquiac, central Mexico, 14,000–7000 B.C.E., bone, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico (Figure 1.1)

Figure 1.1: Camelid sacrum in the shape of a canine, from Tequixquiac, central Mexico, c. 14,000–7000 B.C.E., bone, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico

Materials

■Bone sculpture from a camel-like animal.

■The bone has been worked to create the image of a dog or wolf.

Content

■Carved to represent a mammal’s skull.

■One natural form used to take the shape of another.

■The sacrum is the triangular bone at the base of a spine.

Context

■Mesoamerican idea that a sacrum is a “second skull.”

■The sacrum bone symbolizes the soul in some cultures, and for that reason it may have been chosen for this work.

History

■Found in 1870 in the Valley of Mexico.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 3

Web Source http://research.famsi.org/aztlan/uploads/papers/stross-sacrum.pdf

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: The Depiction of Animals

–Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000) (Figure 29.16)

–Muybridge, The Horse in Motion (Figure 21.5)

–Cotsiogo (also known as Cadzi Cody), Hide Painting of a Sun Dance (Figure 26.13)

Anthropomorphic stele, Arabian Peninsula, 4th millennium B.C.E., sandstone, National Museum, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Figure 1.2)

Form and Content

■Anthropomorphic: resembling human form but not in itself human.

■Belted robe from which hangs a double-bladed knife or sword.

■Double cords stretch diagonally across body with an awl unifying them.

Function

■Religious or burial purpose, perhaps as a grave marker.

Context

■One of the earliest known works of art from Arabia.

■Found in an area that had extensive ancient trade routes.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 6

Web Source https://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/24/arts/24iht-melik24.html?_r=0

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Anthropomorphic Images

–Mutu, Preying Mantra (Figure 29.25)

–Female deity from Nukuoro (Figure 28.2)

–Braque, The Portuguese (Figure 22.6)

Figure 1.2: Anthropomorphic stele, Arabian Peninsula, 4th millennium B.C.E., sandstone, National Museum, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

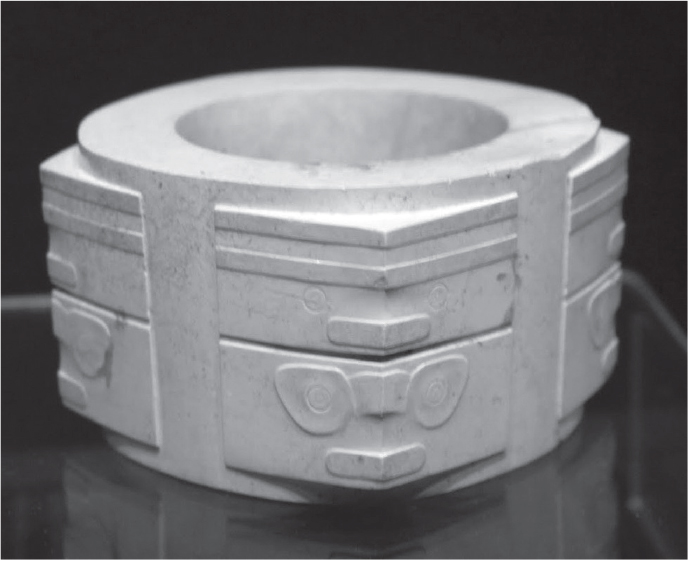

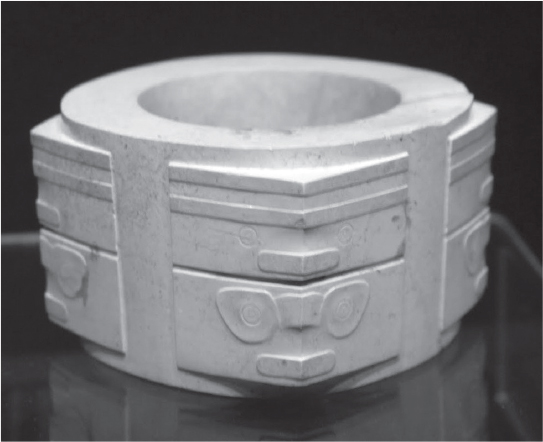

Jade cong from Liangzhu, China, c. 3300–2200 B.C.E., carved jade, Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, China (Figure 1.3)

Form

■Circular hole placed within a square.

■Abstract designs; the main decoration is a face pattern, perhaps of spirits or deities.

■Some have a haunting mask design in each of the four corners—with a bar-shaped mouth, raised oval eyes, sunken round pupils, and two bands that might indicate a headdress—resembles the motif seen on Liangzhu jewelry.

Figure 1.3: Jade cong from Liangzhu, China, c. 3300–2200 B.C.E., carved jade, Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, China

Materials and Techniques

■Jade is a very hard stone, sometimes carved using drills or saws.

■The designs on congs may have been produced by rubbing sand.

■The jades may have been heated to soften the stone, or ritually burned as part of the burial process.

Context

■Jades appear in burials of people of high rank.

■Jades are placed in burials around bodies; some are broken, and some show signs of intentional burning.

■Jade religious objects are of various sizes and found in tombs, interred with the dead in elaborate rituals.

■The Chinese linked jade with the virtues of durability, subtlety, and beauty.

■Many of the earliest and most carefully finished examples (the result of months of laborious shaping by hand) are comparatively compact.

■Made in the Neolithic era in China.

Theory

■Later works have these characteristics: rectilinear quality symbolizes the earth; central circular hole represents the sky. It is not known if these characteristics apply to these earlier works as well.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 7

Web Source http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2018/05/31/36449097.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Geometric Designs

–Mondrian, Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow (Figure 22.14)

–Relief Sculpture from Chavín de Huántar (Figure 26.1c)

–Martínez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel (Figure 26.14)

The Ambum Stone from Ambum Valley, Enga Province, Papua New Guinea, c. 1500 B.C.E., graywacke, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (Figure 1.4)

Form

■Composite human/animal figure; perhaps an anteater head and a human body.

■Ridge line runs from nostrils, over the head, between the eyes, and between the shoulders.

Theories

■Masked human.

■Anteater embryo in a fetal position; anteaters thought of as significant because of their fat deposits.

■May have been a pestle or related to tool making.

■Perhaps had a ritual purpose; considered sacred; maybe a fertility symbol.

■Maybe an embodiment of a spirit from the past, an ancestral spirit, or the Rainbow Serpent.

History

■Stone Age work; artists used stone to carve stone.

■Found in the Ambum Valley in Papua New Guinea.

■When it was “found,” it was being used as a ritual object by the Enga people.

■Sold to the Australian National Gallery.

■Damaged in 2000 when it was on loan in France; it was dropped and smashed into three pieces and many shards; it has since been restored.

Figure 1.4: The Ambum Stone from Ambum Valley, Enga Province, Papua New Guinea, c. 1500 B.C.E., graywacke, National Gallery of Australia—Canberra

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 9

Web Source http://nga.gov.au/AmbumStone/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Animal Forms

–Detail from the Lakshmana Temple (Figure 23.7c)

–Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000) (Figure 29.16)

–Buk (mask) (Figure 28.9)

Tlatilco female figurine, Central Mexico, site of Tlatilco, c. 1200–900 B.C.E., ceramic, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, New Jersey (Figure 1.5)

Form

■Flipper-like arms, huge thighs, pronounced hips, narrow waists.

■Unclothed except for jewelry; arms extending from body.

■Diminished role of hands and feet.

■Female figures show elaborate details of hairstyles, clothing, and body ornaments.

Technique

■Made by hand; artists did not use molds.

Function

■May have had a shamanistic function.

Context and Interpretation

■Some show deformities, including a female figure with two noses, two mouths, and three eyes, perhaps signifying a cluster of conjoined or Siamese twins and/or stillborn children.

■Bifacial images and congenital defects may express duality.

■Found in graves, and may have had a funerary context.

Tradition

■Tlatilco, Mexico, an area noted for pottery.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 10

Web Source http://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/39164

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Human Figure

–Veranda post (Figure 27.14)

–Power figure (Figure 27.6)

–Reliquary of Sainte-Foy (Figure 11.6c)

Figure 1.5: Tlatilco female figurine, Central Mexico, site of Tlatilco, c. 1200–900 B.C.E., ceramic, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, New Jersey

Terra cotta fragment, Lapita, Reef Islands, Solomon Islands, 1000 B.C.E., incised terra cotta, University of Auckland, New Zealand (Figure 1.6)

Form

■Pacific art is characterized by the use of curved stamped patterns: dots, circles, hatching; may have been inspired by patterns on tattoos.

■One of the oldest human faces in Oceanic art.

Materials

■Lapita culture of the Solomon Islands is known for pottery.

■Outlined forms: they used a comb-like tool to stamp designs onto the clay, known as dentate stamping.

Figure 1.6: Terra cotta fragment, Reef Islands, Solomon Islands, 1000 B.C.E., incised terra cotta, University of Auckland, New Zealand (Photo: plaster copy in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Technique

■Did not use potter’s wheel.

■After pot was incised, a white coral lime was often applied to the surface to make the patterns more pronounced.

Tradition

■Continuous tradition: some designs found on the pottery are used in modern Polynesian tattoos and tapas.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 11

Web Source for Lapita Pottery http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/lapi/hd_lapi.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Motifs in Pacific Art

–Hiapo (Figure 28.6)

–Malagan mask (Figure 28.8)

–Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene (Figure 28.7)

Prehistoric Painting

Most prehistoric paintings that survive exist in caves, sometimes deeply recessed from their openings. Images of animals dominate with black outlines emphasizing their contours. Paintings appear to be placed about the cave surface with no relationship to one another. Indeed, cave paintings may have been executed over the centuries by various groups who wanted to establish a presence in a given location.

Although animals are realistically represented with a palpable three-dimensionality, humans are depicted as stick figures with little anatomical detail.

Handprints abound in cave paintings, most of them as negative prints, meaning that a hand was placed on the wall and paint blown or splattered over it, leaving a silhouette. Since most people are right-handed, the handprints are generally of left hands, the right being used to apply the paint. Handprints occasionally show missing joints or fingers, perhaps indicating that prehistoric people practiced voluntary mutilation. However, the thumb, the most essential finger, is never harmed.

Apollo 11 stones, c. 25,500–25,300 B.C.E., charcoal on stone, State Museum of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia (Figure 1.7)

Form

■Animal seen in profile, typical of prehistoric painting.

■Perhaps a composite animal rather than a particular specimen.

Materials

■Done with charcoal.

Context

■Some of the world’s oldest works of art, found in Wonderwerk Cave in Namibia.

■Several stone fragments found.

■Originally brought to the site from elsewhere.

■Cave is the site of 100,000 years of human activity.

History

■Named after the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, the year the cave was discovered.

Figure 1.7: Apollo 11 stones, c. 25,500–25,300 B.C.E., charcoal on stone, State Museum of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 1

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/toah/hd/apol/hd_apol.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Figures in Profile

–Grave stele of Hegeso (Figure 4.7)

–Tomb of the Triclinium (Figure 5.3)

–Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and three daughters (Figure 3.10)

Great Hall of the Bulls, Paleolithic Europe, 15,000–13,000 B.C.E., rock painting, Lascaux, France (Figure 1.8)

Content

■650 paintings: most common animals are cows, bulls, horses, and deer.

Form

■Bodies seen in profile; frontal or diagonal view of horns, eyes, and hooves; some animals appear pregnant.

■Twisted perspective: many horns appear more frontal than the bodies.

■Many overlapping figures.

Figure 1.8: Great Hall of the Bulls, Paleolithic Europe, 15,000–13,000 B.C.E., rock painting, Lascaux, France

Materials

■Natural products were used to make paint: charcoal, iron ore, plants.

■Walls were scraped to an even surface; paint colors were bound with animal fat; lamps lighted the interior of the caves.

■No brushes have been found.

–May have used mats of moss or hair as brushes.

–Color could have been blown onto the surface by mouth or through a tube, like a hollow bone.

Context

■Animals placed deep inside cave—some hundreds of feet from the entrance.

■Evidence still visible of scaffolding erected to get to higher areas of the caves.

■Negative handprints: are they signatures?

■Caves were not dwellings, as prehistoric people led migratory lives following herds of animals; some evidence exists that people did seek shelter at the mouths of caves.

Theories

■A traditional view is that they were painted to ensure a successful hunt.

■Ancestral animal worship.

■Represents narrative elements in stories or legends.

■Shamanism: a religion based on the idea that the forces of nature can be contacted by intermediaries, called shamans, who go into a trancelike state to reach another state of consciousness.

History

■Discovered in 1940; opened to the public after World War II.

■Closed to the public in 1963 because of damage from human contact.

■Replica of the caves opened adjacent to the original.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 2

Web Source http://www.lascaux.culture.fr/?lng=en#/en/00.xml

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Mural Paintings

–Tomb of the Triclinium (Figure 5.3)

–Leonardo da Vinci, Last Supper (Figure 16.1)

–Walker, Darkytown Rebellion (Figure 29.21)

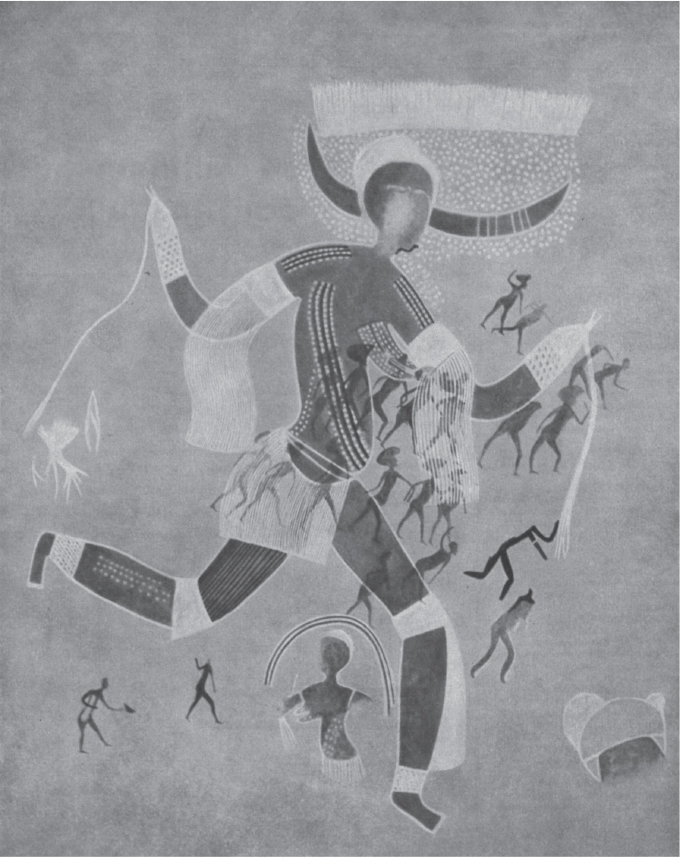

Running horned woman, 6000–4000 B.C.E., pigment on rock, Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria (Figure 1.9)

Form

■Composite view of the body.

■Many drawings exist—some are naturalistic, some are abstract, some have Negroid features, and some have Caucasian features.

■The female horned figure suggests attendance at a ritual ceremony.

Content

■Depicts livestock (cows, sheep, etc.); wildlife (giraffes, lions, etc.); humans (hunting, harvesting, etc.).

■Dots may reflect body paint applied for ritual or scarification; white patterns in symmetrical lines may reflect raffia garments.

Context

■More than 15,000 drawings and engravings were found at this site.

■At one time the area was grasslands; climate changes have turned it into a desert.

■The entire site was probably painted by many different groups over large expanses of time.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 4

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/179

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Masks and Headdresses

–Aka elephant mask (Figure 27.12)

–Ikenga (shrine figure) (Figure 27.10)

–Malagan mask (Figure 28.8)

Figure 1.9: Running horned woman, 6000–4000 B.C.E., pigment on rock, Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria

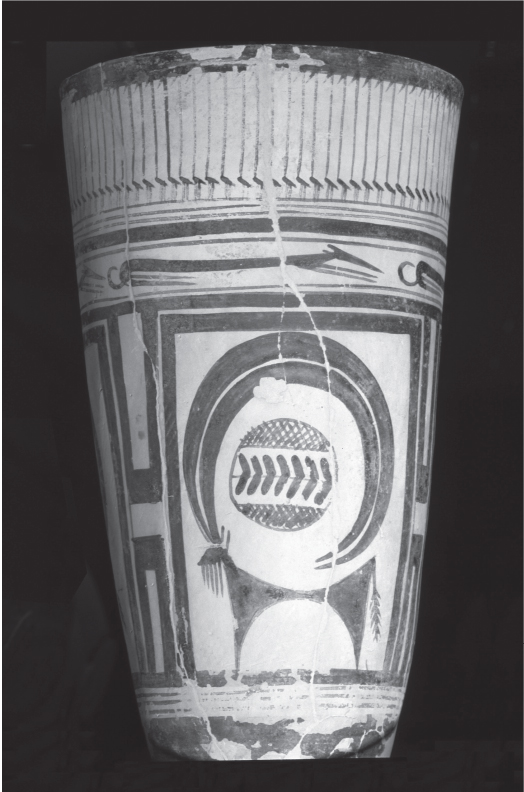

Beaker with ibex motifs, Susa, Iran, 4200–3500 B.C.E., painted terra cotta, Louvre, Paris (Figure 1.10)

Form and Content

■Frieze of stylized aquatic birds on top, suggesting a flock of birds wading in a Mesopotamian river valley.

■Below are stylized running dogs with long narrow bodies, perhaps hunting dogs.

■The main scene shows an ibex with oversized abstract and stylized horns.

Materials and Techniques

■Probably made on a potter’s wheel, a technological advance; some suggest instead that it was handmade.

■Thin pottery walls.

Context and Interpretation

■In the middle of the horns is a clan symbol of family ownership; perhaps the image identifies the deceased as belonging to a particular group or family.

■Found near a burial site, but not with human remains.

■Found with hundreds of baskets, bowls, and metallic items.

■Made in Susa, in southwestern Iran.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 5

Web Source http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/bushel-ibex-motifs

Figure 1.10: Beaker with ibex motifs, Susa, Iran, 4200–3500 B.C.E., painted terra cotta, Louvre, Paris

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ceramics

–Martínez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel (Figure 26.14)

–The David Vases (Figure 24.11)

–Koons, Pink Panther (Figure 29.9)

Prehistoric Architecture

Prehistoric people were known to build shelters out of large animal bones heaped in the shape of a semicircular hut. However, the most famous structures were not for habitation but almost certainly for worship. Sometimes menhirs, or large individual stones, were erected singularly or in long rows stretching into the distance. Menhirs cut into rectangular shapes and used in the construction of a prehistoric complex are called megaliths. A circle of megaliths, usually with lintels placed on top, is called a henge. These were no small accomplishments, since these Neolithic structures may have been built to align with the important dates in the calendar. Prehistoric people built structures in which two uprights were used to support a horizontal beam, thereby establishing post-and-lintel (Figure 1.11) architecture, the most fundamental type of architecture in history.

Figure 1.11: Post-and-lintel construction

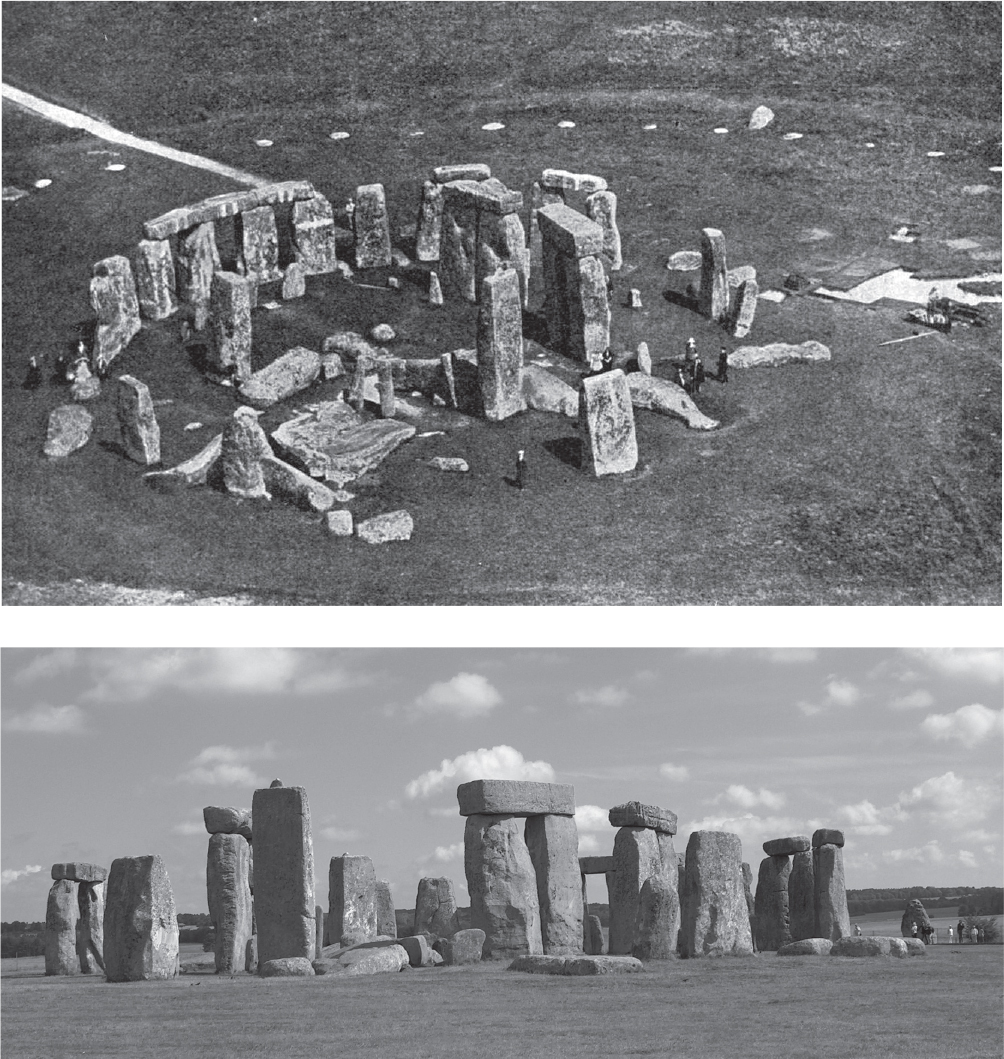

Stonehenge, c. 2500–1600 B.C.E., sandstone, Neolithic Europe, Wiltshire, United Kingdom (Figures 1.12a and 1.12b)

Technique

■Post-and-lintel building; lintels grooved in place by the mortise and tenon system of construction.

■Large megaliths in the center are over 20 feet tall and form a horseshoe surrounding a central flat stone.

■A ring of megaliths, originally all united by lintels, surrounds a central horseshoe.

■Hundreds of smaller stones of unknown purpose were placed around the monument.

■Builders did not have the wheel or pulleys. Stones may have been rolled on logs or on a sleigh greased with animal fat to get them to the site.

Context

■Some stones weigh more than 50 tons; the size of each stone reflects the intended permanence of the structure.

■Some stones were imported from over 150 miles away, an indication that the stones must have had a special or sacred significance.

Figures 1.12a and 1.12b: Stonehenge, c. 2500–1600 B.C.E., sandstone, Neolithic Europe, Wiltshire, United Kingdom

History

■Perhaps took 1,000 years to build; gradually redeveloped by succeeding generations.

■Probably built in three phases:

–First Phase: circular ditch 36 feet deep and 360 feet in diameter containing 56 pits called Aubrey Holes, named after John Aubrey who found them in the eighteenth century. Today the holes are filled with chalk.

–Second Phase: wooden structure, perhaps roofed. The Aubrey Holes may have been used as cremation burials at this time. Adult males were buried at these sites, generally men who did not show a lifetime of hard labor, signifying it was a site for a select group of people.

–Third Phase: stone construction.

Tradition

■May have been inspired by previously erected wood circles; the British Isles are rich in forested areas.

■Stone circles are a common sight, even today, in Great Britain, indicating great popularity in the Neolithic world.

Theories

■Generally thought to be oriented toward sunrise at the summer solstice (the longest day of the year) and sunset at the winter solstice; may also predict eclipses, acting as a kind of observatory.

■A new theory posits that Stonehenge was the center of ceremonies concerning death and burial; elite males were buried here.

■An alternate theory suggests it was a site used for healing the sick.

Content Area Global Prehistory, Image 8

Web Source http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/stonehenge/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ritual Centers

–Chavín de Huántar (Figures 26.1a, 26.1b)

–Pantheon (Figures 6.11a, 6.11b)

–Great Mosque of Djenné (Figure 27.2)

VOCABULARY

Anthropomorphic: having characteristics of the human form, although the form itself is not human (Figure 1.2)

Archaeology: the scientific study of ancient people and cultures principally revealed through excavation

Cong: a tubular object with a circular hole cut into a square-like cross section (Figure 1.3)

Henge: a Neolithic monument, characterized by a circular ground plan. Used for rituals and marking astronomical events (Figure 1.12b)

Lintel: a horizontal beam over an opening (Figure 1.12)

Megalith: a stone of great size used in the construction of a prehistoric structure

Menhir: a large uncut stone erected as a monument in the prehistoric era; a standing stone

Mortise and tenon: a groove cut into stone or wood, called a mortise, that is shaped to receive a tenon, or projection, of the same dimensions

Post-and-lintel: a method of construction in which two posts support a horizontal beam, called a lintel (Figure 1.11)

Shamanism: a religion in which good and evil are brought about by spirits which can be influenced by shamans, who have access to these spirits

Stele (plural: stelae): an upright stone slab used to mark a grave or a site (Figure 1.2)

Stylized: a schematic, nonrealistic manner of representing the visible world and its contents, abstracted from the way that they appear in nature (Figure 1.2)

SUMMARY

Prehistoric works of art have the power to amaze and intrigue viewers in the modern world, even though so little is known about their original intention, creation, or meaning. The creative impulse exists with the earliest of human endeavors, as is evidenced by the cave paintings from Lascaux and sculptures such as the anthropomorphic stele. The first type of construction, the post-and-lintel method, was developed during the Neolithic period to build monumental structures like Stonehenge.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.A number of theories have been proposed about the purpose of the Lascaux Cave paintings. Among the likely theories is

(A)prehistoric kings believed they absorbed the power of the animals

(B)the drawings reflected primitive masks used for ritual purposes

(C)shamans perhaps entered into a trancelike state before the paintings

(D)they illustrate the first occurrence of ritual tattooing

2.The unusual anatomical shapes of the Tlatilco female figures probably indicate

(A)a cluster of unusual congenital abnormalities

(B)the influence of similar works produced in Southeast Asia

(C)a reliance on artistic traditions going back to cave paintings

(D)their placement in ritual centers that emphasized the triumph of death over the mundane world of the living

3.Prehistoric images of people wearing masks, such as the “running horned woman,” indicate an ancient interest in

(A)coronation of royalty and a sophisticated power structure

(B)a formal hierarchy of religious leaders, including women

(C)ceremonial centers and designated performers

(D)ritual presentations in which the participants paint their bodies and dance

4.The “beaker with ibex motifs” was found at a site in the city of Susa, indicating that it was used

(A)as part of a burial tradition

(B)in business transactions

(C)in a domestic setting

(D)for governmental correspondence

5.Many works of prehistoric art had a funerary purpose as can be seen in

(A)the running horned woman who is escaping an enemy

(B)the Ambum Stone, which represents a sacred animal in a deathlike pose

(C)the camelid sacrum, which is carved from a dead animal

(D)the jade cong, which is found in a burial site

Short Essay

Since the global prehistoric unit is such a small proportion of the testing material, the College Board has indicated that it is not likely that a short essay question will appear on this subject. However, an essay question is presented here so that students can practice a contextual analysis essay.

Practice Question 4: Contextual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

This jade cong was made in Neolithic China. It has a function that can be surmised from the site it is associated with.

Where were jade congs found?

What symbolic associations did jade have to the Chinese?

What can be understood about jade congs given the context of their find spots?

Describe the images done in relief on the cong, and interpret their contextual meanings.

ANSWER KEY

1.C

2.A

3.D

4.A

5.D

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(C) Shamans may have been involved in trancelike experiences before the paintings. Since there is only one human on the walls, a stick figure at that, there is no evidence of tattooing. No aristocracy is known in the prehistoric world in England and France. Prehistoric masks from this time do not survive.

2.(A) According to modern theories, the unusual anatomical shapes may have been a reflection of a fascination with several congenital abnormalities centered in the Tlatilco in Mexico. There is no cave painting tradition in this area, nor are there influences from other parts of the world. Their original placement is unknown.

3.(D) Rituals were important aspects of prehistoric culture; hence, they are depicted fairly regularly in the prehistoric art that survives in Africa.

4.(A) The beaker was found at a burial site and was used for mortuary purposes, although no trace of human remains was found inside.

5.(D) The Chinese jade cong was found in a burial site. There is no indication that any of the other works were used for funerary purposes.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Where were jade congs found? |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Jades appear in burials of people of high rank. ■Jade religious objects found in tombs; interred with the dead in elaborate rituals. |

What symbolic associations did jade have to the Chinese? |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Jade was treasured by the Chinese for its durability and its color. ■Jade buried along with the dead indicates a special reverence for the dead. ■Chinese linked jade with virtues: durability, subtlety, beauty. ■Jade must have possessed a special spiritual quality since it was found in so many burials. |

What can be understood about jade congs given the context of their find spots? |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Placed in burials around bodies; some are broken, and some show signs of intentional burning. ■Jade congs have a spiritual significance. |

Describe the images done in relief on the cong… |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Abstract designs; main decoration is a face pattern, perhaps of spirits or deities. ■Four corners of the cong usually carry masklike images with pronounced eyes and a fanged mouth. ■Some have a haunting mask design in each of the four corners—with a bar-shaped mouth, raised oval eyes, sunken round pupils, and two bands that might indicate a headdress—which resembles the motif seen on Liangzhu jewelry. |

…and interpret their contextual meanings. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Designs represent human, animal, or spiritual faces in a stylized manner. |