Content Area: Africa, 1100–1980 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: FROM PREHISTORIC TIMES TO THE PRESENT

Some chief African civilizations include:

| Civilization | Time Period | Location |

| Great Zimbabwe | 11th–15th Centuries | Zimbabwe |

| Bamileke | 11th–21st Centuries | Cameroon |

| Benin | 13th–19th Centuries | Nigeria |

| Luba | 16th–21st Centuries | Congo |

| Kuba | 17th–19th Centuries | Congo |

| Ashanti | 17th–21st Centuries | Ghana |

| Chokwe | 17th–21st Centuries | Congo |

| Yoruba | 17th–21st Centuries | Nigeria |

| Baule | 19th–21st Centuries | Côte d’Ivoire |

| Igbo | 19th–21st Centuries | Nigeria |

| Fang | 19th–21st Centuries | Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea |

| Mende | 19th–21st Centuries | Sierra Leone |

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Bundu mask)

Essential Knowledge:

■African art is seen as a combination of the work of art itself in the context of events, media, and ceremonies. There is a wide variety of materials used in African art.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Lukasa (memory board))

Essential Knowledge:

■Human life began in Africa. African art makes its first appearance around 77,000 years ago.

■Rock art is the earliest form of African art. Animals are depicted most often.

■The Sahara was once a vast grassland.

■African art is often rooted in belief systems and ideas. It is more concerned with the spiritual and intellectual than the physical.

■African art is involved in important stages of human life.

■Important civic and religious centers are often placed apart from places that involve herding or agriculture.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Aka elephant mask)

Essential Knowledge:

■African art has been impacted by migration, world religions, and international trade.

■For many years, African art has been thought of as primitive by the outside world. However, African art is now understood as a vibrant series of artistic traditions.

■Contemporary African art understands artistic influences from around the world.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Mblo)

Essential Knowledge:

■African art is participatory. The arts express beliefs and maintain social and human relationships.

■African works are meant to be used and performed rather than simply viewed.

■Art is created for everyday use and important occasions. The object generally belongs to the person who commissioned it. Performances are highly organized.

■When an artwork represents authority, it legitimizes a leader.

■African art is presented to audiences through song and dance for specific reasons.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Great Zimbabwe)

Essential Knowledge:

■African art has been generally collected by outsiders. Generally, the artist’s name and the date of creation are not known.

■Art history as a science is subject to differing interpretations and theories that change over time.

■African art has had a global impact.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Despite the incredible vastness of the African continent, there are a number of similarities in the way in which African artists create art, stemming from common beliefs they share.

Africans believe that ancestors never die and can be addressed; hence a sense of family and a respect for elders are key components of the African psyche. Many African sculptures are representations of family ancestors and were carved to venerate their spirits.

Fertility, both of the individual and the land, is highly regarded. Spirits who inhabit the forests or are associated with natural phenomenon have to be respected and worshipped. Sculptures of suckling mothers are extremely common; it is implied that everyone suckles from the breast of God.

Great ancient civilizations in Nubia, Egypt, and Carthage dominated politics in North Africa for centuries before empires began to develop in southern Africa, or much of the rest of the world.

African kingdoms came and went with regularity; more populous and dominant people occupied wide swaths of African territory. Strong indigenous states were established in Christian Aksum in present-day Ethiopia in the fourth century, and in the Luba Empire concentrated in central Africa beginning in the fifteenth century. In the twelfth century an important center evolved in southern Africa on the Zimbabwe plateau. Whatever the location, African states developed strong cultural traditions yielding a great variety of artistic expression.

African affairs were largely internal struggles because outsiders were held back by natural barriers like the Sahara Desert and the Indian Ocean. However, by the fifteenth century African politics became greatly complicated by Asian and European incursions on both the east and west coasts of the continent. In general, outsiders restricted themselves to coastal areas that afforded the most access to African goods, and few bothered with the interior of the continent. All this changed in the late nineteenth century when a large series of invasions called the Scramble for Africa divided the continent into colonies.

The era of European control spanned less than a century. Most states achieved independence in the 1960s, with the Portuguese colonies waiting until the 1970s. Colonization brought African cultural affairs in direct contact with the rest of the world. Today African artists work both at home and abroad, using native and foreign materials, and marketing their work on a global scale.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Since traditional Africans rely on an oral tradition to record their history, African objects are unsigned and undated. Although artists were famous in their own communities and were sought after by princes, written records of artistic activity stem principally from European or Islamic explorers who happened to encounter artists in their African journeys.

African artists worked on commission, often living with their patrons until the commission was completed. The same apprenticeship training that was current in Europe was the standard in Africa as well. Moreover, Africans also had guilds that promoted their work and helped elevate the profession.

As a rule, men were builders and carvers and were permitted to wear masks. Women painted walls and created ceramics. Both sexes were weavers. There were exceptions; for example, in Sierra Leone and Liberia women wore masks during important coming-of-age ceremonies.

The most collectable African art originated in farming communities rather than among nomads, who desired portability. To that end, the more nomadic people of East Africa in Kenya and Tanzania produced a fine school of body art, and the more agricultural West Africans around Sierra Leone and Nigeria achieved greatness with bronze and wood sculpture.

African art was imported into Europe during the Renaissance more as curiosities than as artistic objects. It was not until the early twentieth century that African art began to find true acceptance in European artistic circles.

AFRICAN ARCHITECTURE

Traditional African architecture is built to be as cool and comfortable as a building could get in the hot African sun, and therefore is made of mud-brick walls and thatched roofs. While mud brick is certainly easy and inexpensive to make, it has inherent problems. All mud-brick buildings have to be meticulously maintained in the rainy season; otherwise, much would wash away. Nonetheless, Africans build huge structures of mud brick with horizontally placed timbers as maintenance ladders.

In a culture that generally eschews stonework, both in its architecture and its sculpture, the royal complex at Zimbabwe (Figure 27.1) from the fourteenth century is most unusual. The sophisticated handling of this type of masonry implies a long-standing tradition of construction of permanent materials, traces of which have all but been lost.

Great Zimbabwe, Shona peoples (Southeastern Zimbabwe), c. 1000–1400, coursed granite blocks, Zimbabwe (Figures 27.1a and 27.1b)

Form

■Walls: 800 feet long, 32 feet tall; 17 feet thick at base.

■Walls slope inward toward the top; made of exfoliated granite blocks.

Figure 27.1a: Conical tower of Great Zimbabwe, c. 1000–1400, coursed granite blocks, Zimbabwe

Figures 27.1b: Circular wall of Great Zimbabwe

Function

■Zimbabwe was a prosperous trading center and royal complex; items from as far away as Persia and China have been found.

■Stone enclosure was probably a royal residence.

Context

■Zimbabwe derives from a Shona term meaning “venerated houses” or “houses of stone.”

■Internal and external passageways are tightly bounded, narrow, and long; occupants are forced to walk in single file, paralleling experiences in the African bush.

■The conical tower is modeled on traditional shapes of grain silos; control over food symbolized wealth, power, and royal largesse.

■The tower resembles a granary and represented a good harvest and prosperity; grain gathered, stored, and dispensed as a symbol of royal power.

■Abandoned in the fifteenth century probably because the surrounding area could no longer supply food and there was extensive deforestation.

Content Area Africa, Image 167

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/364

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ashlar Masonry

–Saqsa Waman (Figure 26.8c)

–Angkor Wat (Figure 23.8a)

–Pantheon (Figures 6.11a, 6.11b)

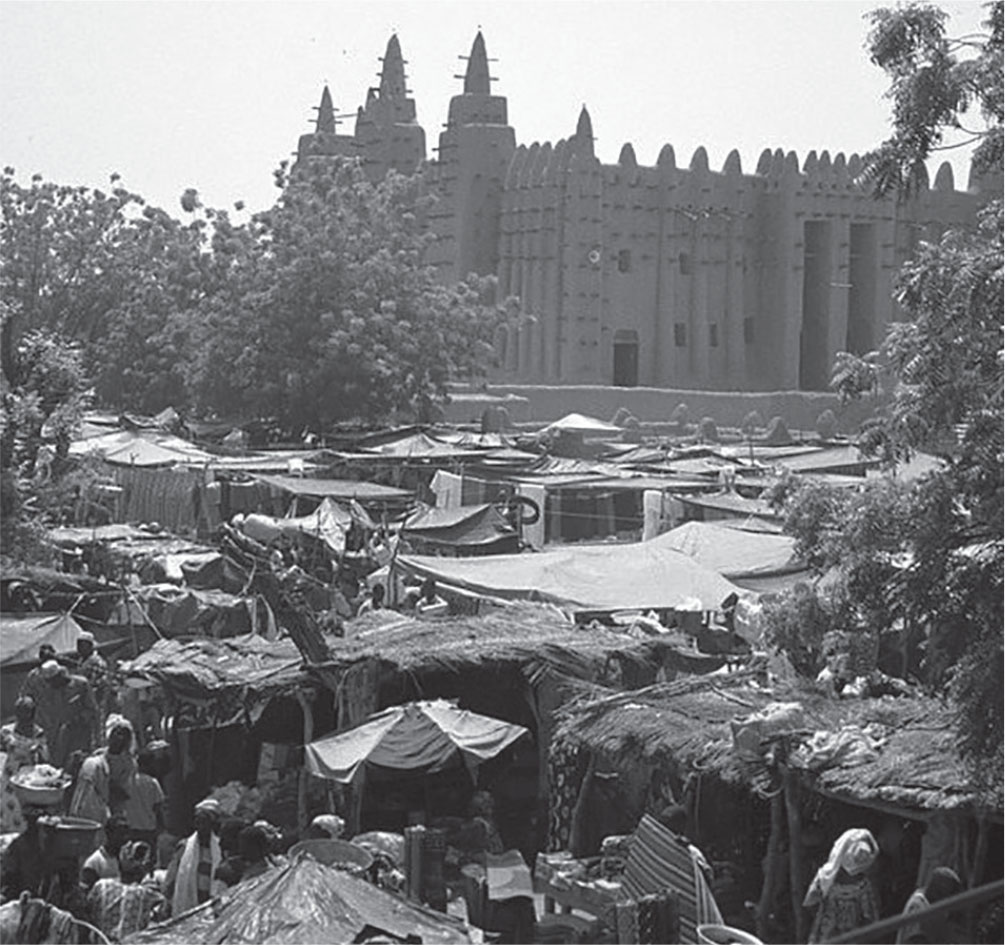

Great Mosque, founded c. 1200, rebuilt 1906–1907, adobe, Djenné, Mali (Figure 27.2)

Figure 27.2: Great Mosque, founded c. 1200, rebuilt 1906–1907, adobe, Djenné, Mali

Form

■Three tall towers; center tower is a mihrab.

■Vertical fluting drains water off the surfaces quickly.

Materials

■Made of adobe, a baked mixture of clay and straw; adobe helps maintain cooler temperatures.

■Torons: wooden beams projecting from walls.

■Wooden beams act as in-place ladders for the maintenance of the building.

Function

■Largest mud-brick mosque in the world.

Content

■Crowning ornaments have ostrich eggs, symbols of fertility and purity.

■Roof has several holes with terra cotta lids to circulate air into the main room.

Context

■Inhabited since 250 B.C.E., Djenné became a market center and an important link in the trans-Saharan gold trade.

■Two thousand traditional houses survive, built on small hills to protect against seasonal floods.

■Once a year there is a community activity to repair the mosque called Crepissago de la Grand Mosquée.

Content Area Africa, Image 168

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/116

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Other Mosques

–Great Mosque, Córdoba (Figures 9.14a, 9.14b, 9.14c)

–Mosque of Selim II (Figures 9.16a, 9.16b, 9.16c)

–Great Mosque, Isfahan (Figures 9.13a, 9.13b, 9.13c)

AFRICAN SCULPTURE

Despite the number of sculptural traditions in Africa, there are certain similarities.

■African art is basically portable. Large sculptures, the kind that grace the plazas of ancient Egypt or Rome, are unknown.

■Wood is the favorite material. Trees were honored and symbolically repaid for the branches taken from them. Ivory is used as a sign of rank or prestige. Metal shows strength and durability, and is restricted to royalty. Stone is extremely rare.

■Figures are basically frontal, drawn full-face, with attention paid to the sides. Symmetry is occasionally used, but more talented artists vary their approach on each side of the object.

■Africans did no preliminary sketches and worked directly on the wood. There is a certain stiffness to all African works.

■Heads are disproportionately large, sometimes one-third of the whole figure. Sexual characteristics are also enlarged. Bodies are immature and small. Hands and feet are very small; fingers are rare.

■Multiple media are used. It is common to see wood sculptures adorned with feathers, fabric, or beads.

■African sculpture prefers geometrization of forms. It generally avoids physical reality, representing the spirits in a more timeless world. Proportions are therefore manipulated.

Important sculpture is never created for decoration, but for a definite purpose. African masks are meant to be part of a costume that represents a spirit, and can only come alive when ceremonies are initiated. Every mask has a purpose and represents a different spirit. When the masks are worn in a ceremony, the spirit takes over the costumed dancer and his identity remains unknown—every part of his body is hidden from view. Moved by the beat of a drum, the masked dancer connects with the spirit world and can transmit messages to villagers who are witnesses.

BENIN

Wall plaque, from Oba’s palace, Edo peoples, Kingdom of Benin (Nigeria), 16th century, cast brass, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Figure 27.3a)

Form and Content

■Hierarchical proportions: largest figure is the king.

■Symbols of high rank are emphasized.

■King is stepping on a fallen leader.

■Emphasis on heads; bodies are often small and immature.

■Ceremonial scene at court.

Technique

■High-relief sculpture.

■Lost-wax process.

Figure 27.3a: Wall plaque, from Oba’s palace, Edo peoples, Kingdom of Benin (Nigeria), 16th century, cast brass, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Materials

■One of 900 brass plaques produced, each between 16 and 18 inches.

■Metal products are rare in Africa, making these objects extremely valuable.

■There was an active trade with the Portuguese for brass.

Function

■It decorated the walls of the royal palace in Benin.

■It was part of a sprawling palace complex; wooden pillars covered with brass plaques.

Context

■Shows aspects of court life in the Benin culture.

■Cross-cultural influences:

–The horse, an animal imported into Africa.

–Rosette shapes inspired by Christian crosses from Europe.

–May have been executed to reflect European books and prints that were available in Africa.

–Imported goods reflected status: i.e., the king wears necklaces of coral.

■The oba (king) was believed to be a direct descendant of Oranmiyan, the legendary founder of the dynasty.

■Only the oba was allowed to be shielded in the way depicted on the plaque.

Content Area Africa, Image 169

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/310752

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Bronze and Brass Work

–Donatello, David (Figure 15.5)

–Great Buddha at Todai-ji (Figure 25.1b)

–Shiva as Lord of Dance (Figure 23.6)

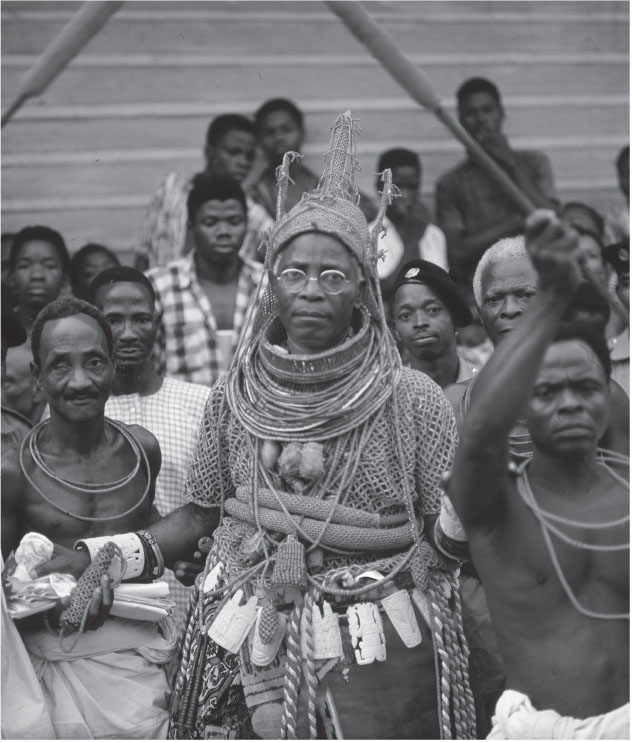

CONTEXTUAL IMAGE

The late Oba Akenzua II in full regalia, including a coral garment and headpiece (Figure 27.3b)

Figure 27.3b: The late Oba Akenzua II in full regalia, including a coral garment and headpiece

Context

■Coral is an important symbol of the identity of the oba, ruler of the land, with Olokun, ruler of the sea.

■Regalia reflects a continuous tradition of kingship and royal attire from the sixteenth century to the present.

■Photo dated December 24, 1964

Content Area Africa, Image 169

ASHANTI

Golden Stool (sika dwa kofi), Ashanti peoples (south central Ghana) c. 1700, gold over wood, and cast gold attachments, location unknown (Figure 27.4)

Figure 27.4: Golden Stool (sika dwa kofi), Ashanti peoples (south central Ghana) c. 1700, gold over wood, and cast gold attachments, location unknown

Form

■Entire surface inlaid with gold.

■Bells hang from the side to warn the king of danger.

■Replicas often used in ceremonies, but each replica is different.

Function

■Symbol of the Ashanti nation, in Ghana.

■Contains the soul of the nation.

■Never actually used as a stool; never allowed to touch the ground; it is placed on a stool of its own.

■According to Ashanti tradition, it was brought down from heaven by a priest and fell into the lap of the Ashanti king, Osei Tutu.

■It became the repository of the spirit of the nation; it is the symbol of the mystical bond among all Ashanti.

Context

■A new king is raised over the stool.

■The stool is carried to the king on a pillow; he alone is allowed to touch it.

■Taken out on special occasions.

■War of the Golden Stool: March–September 1900:

–Conflict over British sovereignty in Ghana (formerly the Gold Coast).

–A British representative who tried to sit on the stool caused an uproar and a subsequent rebellion.

–The war ended with British annexation and Ashanti de facto independence.

Content Area Africa, Image 170

Web Source https://www.britannica.com/topic/Golden-Stool

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Sacred Objects

–the Kaaba (Figure 9.11a)

–Lanzón Stone (Figure 26.1b)

–Gold and jade crown (Figure 24.10)

KUBA

Ndop (portrait figure) of King Mishe miShyaang maMbul, Kuba peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1760–1780, wood, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York (Figure 27.5a)

Figure 27.5a: Ndop (portrait figure) of King Mishe miShyaang maMbul, Kuba peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1760–1780, wood, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Form

■Characteristics of a ndop:

–Cross-legged pose.

–Sits on a base.

–Epicene body.

–Face seems uninvolved, above mortal affairs.

–A peace knife in his left hand.

■Royal regalia: bracelets, arm bands, belts, headdress.

Function

■Ndop sculptures are commemorative portraits of Kuba rulers, presented in an ideal state.

■Not an actual representation of a deceased king but of his spirit.

■Made after the death of the king.

Context

■Each king is commemorated by symbols on the base of the figure; this king has a sword in his left hand in a nonaggressive pose, handle facing out.

■One of the earliest existing African wood sculptures; oldest ndop in existence.

■Rubbed with oil to protect it from insects.

■Acted as a surrogate for the king in his absence.

■Kept in the king’s shrine with other works called a set of “royal charms.”

Content Area Africa, Image 171

Web Source https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/4791

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Authority Figures

–Houdon, George Washington (Figure 19.7)

–Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene (Figure 28.7)

–Code of Hammurabi (Figures 2.4a, 2.4b)

CONTEXTUAL IMAGE

Kuba Nyim (ruler) Kot a Mbweeky III in state dress with royal drum in Mushenge, Democratic Republic of the Congo (Figure 27.5b)

Figure 27.5b: Kuba Nyim (ruler) Kot a Mbweeky III in state dress with royal drum in Mushenge, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Form

■Photo of a Kuba king enthroned wearing royal regalia:

–Headdress.

–Necklace of leopard teeth.

–Sword.

–Lance.

–Drums of reign.

–Basket.

■Photo made in 1971, capturing a royal event.

■Costuming extremely elaborate; could weigh 185 pounds; king needed help to move.

Context

■Costuming represents the splendor of king’s court, his greatness, and his responsibilities.

■Symbolizes the king’s wealth, status, power.

■Kuba taste of accumulation of objects.

■Continuous tradition of honoring a Kuba king.

■Ruler often buried with the material after his death.

Content Area Africa, Image 171

KONGO

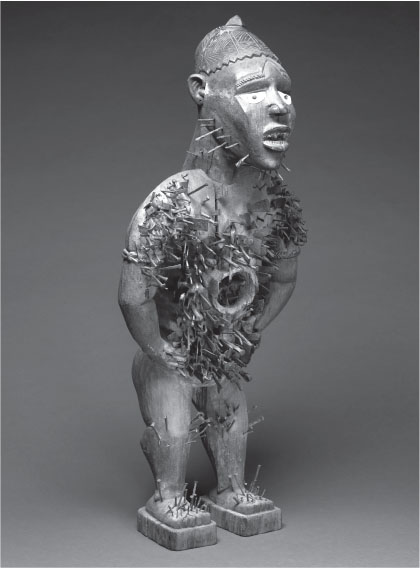

Power figure (Nkisi n’kondi), Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, c. late 19th century, wood and metal, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Figure 27.6)

Figure 27.6: Power figure (Nkisi n’kondi), Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, c. late 19th century, wood and metal, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

■Alert pose.

■Rigid frontality.

■Arms akimbo, in an aggressive stance.

■Wears a headdress worn by chiefs or priests.

■Nails are pounded into the figure.

Function and Context

■Spirits are embedded in the images.

■Spirits can be called upon to bless or harm others, cause death or give life.

■In order to prod the image into action, nails and blades are often inserted into the work or removed from it.

■Medical properties are inserted into the body cavity, thought to be a person’s life or soul.

■The figure has a role as a witness and enforcer of community affairs.

■The figure also cautions people on the consequences of actions contrary to community norms.

Content Area Africa, Image 172

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/320053

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Wood Sculpture

–Röttgen Pietà (Figure 12.7)

–Transformation mask (Figures 26.12a, 26.12b)

–Nio guardian figure (Figures 25.1c, 25.1d)

BAULE

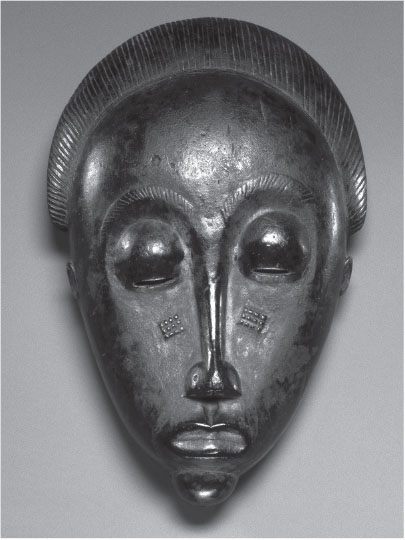

Portrait mask (Mblo), Baule peoples (Côte d’Ivoire), early 20th century, wood and pigment (Figure 27.7)

Figure 27.7: Portrait mask (Mblo), Baule peoples (Côte d’Ivoire), early 20th century, wood and pigment

Form

■Broad forehead, pronounced downcast eye sockets, column-shaped nose: features associated with intellect and respect.

■Quiet faces; introspective look; peaceful face; meditative; eyebrows in an arch.

Function

■Presented at Mblo performances in which an individual is honored with ritual dances; tributes are performed in his or her honor.

■The dancer who wears the mask and wears the clothes of the person for the performance is accompanied by the actual person in the performance.

■The honoree receives a mask—an artistic double of the person—as a gift.

Context

■The masks are commissioned by a group of admirers, not by an individual; this one was made by the artist Owie Kimou.

■The masks are an idealized representation of a real person.

■This is the idealized representation of Moya Yanso.

■From the Ivory Coast.

Content Area Africa, Image 174

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/319512

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Commemoration

–Rivera, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon on the Alameda Park (Figure 22.20)

–Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Figures 29.4a, 29.4b)

–Olmec-style mask (Figure 26.5d)

CHOKWE

Female (Pwo) mask, Chokwe peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, late 19th to early 20th century, wood, fiber, pigment, and metal, National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C. (Figure 27.8)

Figure 27.8: Female (Pwo) mask, Chokwe peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, late 19th to early 20th century, wood, fiber, pigment, and metal, National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C.

Form

■Characteristics:

–Enlarged eye sockets.

–Pushed-in chin.

–Slender nose.

–High forehead.

–Balanced features.

–Almost-closed eyes.

Content

■Marks around the eyes may suggest tears; scarification marks including cosmogram on forehead.

■White powder around the eyes connects the figure to a spiritual realm.

Function

■These are female masks used by men in ritual dances.

■Male dancers are covered with their identities masked; they are dressed as women with braided hair.

■During the ritual, men move like women.

■Depicts female ancestors.

Context

■Chokwe, a matriarchal society.

■The mask is discarded when not in use and can be buried with the dancer.

Content Area Africa, Image 173

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Faces

–Head of a Roman patrician (Figure 6.14)

–Transformation mask (Figures 26.12a, 26.12b)

–Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene (Figure 28.7)

MENDE

Bundu mask, Sande society, Mende peoples (West African forests of Sierra Leone and Liberia), 19th to early 20th century, wood, cloth, and fiber, private collection (Figure 27.9a)

Figure 27.9a: Bundu mask, Sande society, Mende peoples (West African forests of Sierra Leone and Liberia), 19th to 20th century, wood, cloth, and fiber, private collection

Form

■Idealized female beauty, both physically and morally:

–Elaborate hairstyle symbolizes wealth; worn by women of status.

–High forehead indicates wisdom.

–Small eyes in the shape of slits: she should be demure.

–Tight-lipped mouth, symbolizing secrets not revealed.

–Small ears: avoids gossip.

–Rings around the neck symbolize concentric waves from which the water spirit, Sowei, breaks through the surface; also symbolizes the fat associated with a pregnant body.

■Small horizontal features.

Function

■Used for initiation rites to adulthood.

■Used by the elder women of the Sande society, a group of women who prepare girls for adulthood and their role in society.

■Mask rests on woman’s head; head is not placed inside the mask.

■Mask is coated with palm oil for a lustrous effect; it has a shiny black surface.

■Black color symbolizes water, coolness, and humanity.

Context

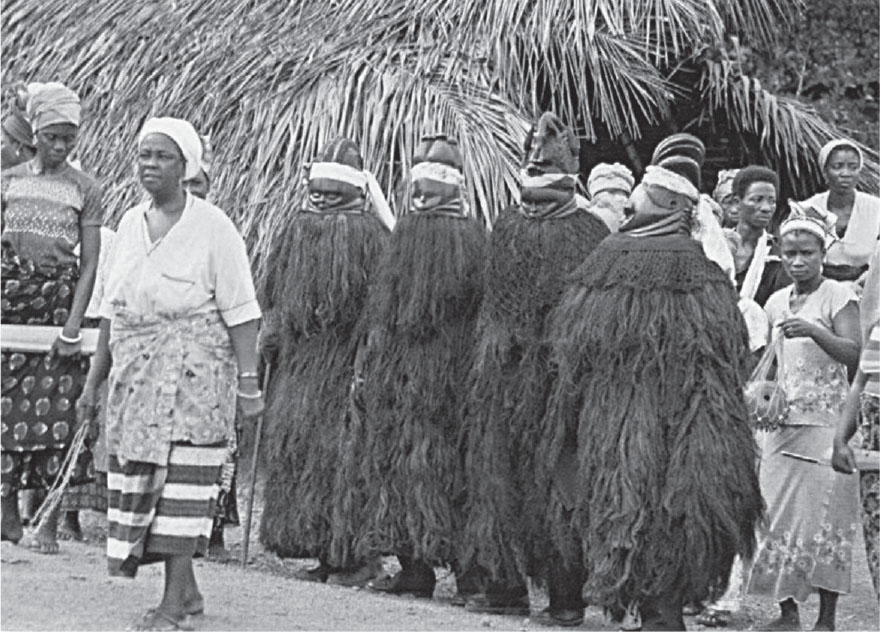

■Only African wooden masks that are worn by women.

■Costumed women wear a black gown made of raffia that hides the body.

■Costumed as a Sowei, the female water spirit.

■Female ancestor spirits.

■Symbolic of the chrysalis of a butterfly; young woman entering puberty.

■Individuality of each mask is stressed.

Content Area Africa, Image 175

Web Source www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/313757

CONTEXTUAL IMAGE

Bundu masks worn in a ceremony (Figure 27.9b)

Figure 27.9b: Bundu masks worn in a ceremony

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Art as Part of a Performance

–Presentation of Fijian mats and tapa cloths to Queen Elizabeth II (Figure 28.10)

–Viola, The Crossing (Figures 29.18a, 29.18b)

–Plaque of the Ergastines (Figure 4.5)

IGBO

Ikenga (shrine figure), Igbo peoples (Nigeria), c. 19th to 20th century, wood, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York (Figure 27.10)

Figure 27.10: Ikenga (shrine figure), Igbo peoples (Nigeria), c. 19th–20th century, wood, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Function and Content

■Ikenga means “strong right arm” and thus physical prowess.

■It honors the right hand, which holds tools or weapons, makes sacrifices, conducts rituals, and alerts to speak at public forums.

■Ikenga embraces traditional masculine associations of strength and potency.

■Often a mix of human, animal, and abstract forms.

■Carved from hardwoods, considered masculine.

■It tells of the owner’s morality, prosperity, achievements, genealogy, and social rank.

Context

■Enormous horns symbolize power.

■Requires blessings before use; consecrated with offerings before kinsmen.

■As the man achieves more success, he might commission a more elaborate version.

■It is maintained in the man’s home and is destroyed when the owner dies; another can reuse it if not destroyed.

Content Area Africa, Image 176

Web Source https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/101836

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Sculpture in the Round

–Kneeling statue of Hatshepsut (Figure 3.9b)

–Rodin, The Burghers of Calais (Figure 21.15)

–Abakanowicz, Androgyne III (Figure 29.7)

LUBA

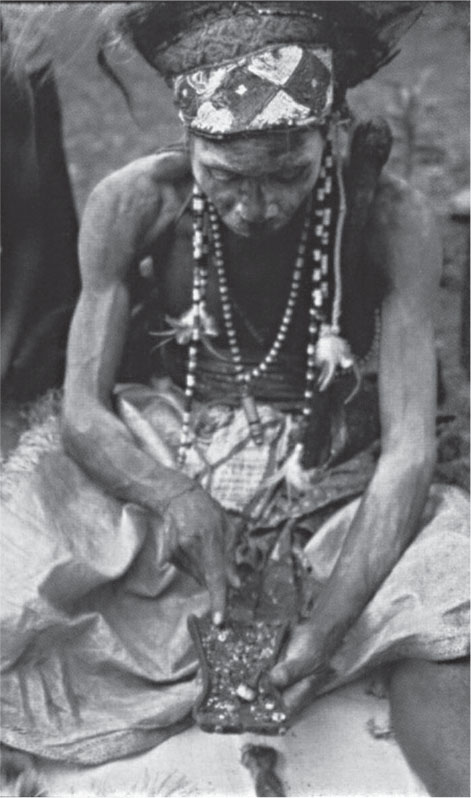

Lukasa (memory board), Mbudye Society, Luba peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, c. 19th to 20th century, wood, beads, and metal, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York (Figures 27.11a and 27.11b)

Figure 27.11a: Lukasa (memory board), Mbudye Society, Luba peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, c. 19th–20th century, wood, beads, and metal, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Figure 27.11b: Court historian using Lukasa (memory board)

Form

■Carved from wood in an hourglass shape and adorned with beads, shells, or metal.

■Back, expressed by Luba people as the “outside,” resembles the shell of a turtle.

Function

■Court historian who serves as reader of the memory board holds the lukasa in his left hand and gently touches the beads that he will discuss with his right index finger.

■Ability to read the board is limited to a few people.

■Memory board helps the user remember key elements in a story; for example:

–Court ceremonies.

–Migrations.

–Heroes.

–Kinship.

–Genealogy.

–Lists of kings.

Context

■Each board’s design is unique and represents the divine revelations of a spirit medium expressed in sculptural form.

■Memory boards are controlled by the Mbudye, a council of men and women who interpret the political and historical aspects of Luba society.

■Zoomorphic elements represented by the turtle, an animal that lives on both land and water; the dual nature of the turtle is a metaphor for the Luba people’s political organization as founded by two distinctly opposed embodiments of power: Kongolo Mwamba, avatar of all excess and tyranny, and Mbidi Kiluwe, sophisticated cultural hero who introduced royal culture to the Luba people.

■Reading example:

–One colored bead can stand for an individual.

–Large beads surrounded by smaller beads can signify a ruler and his court.

–Lines of beads are journeys or paths, migrations or genealogies.

Content Area Africa, Image 177

Web Source https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/102210

CONTEXTUAL IMAGE

Court historian using lukasa (memory board) (Figure 27.11b)

BAMILEKE

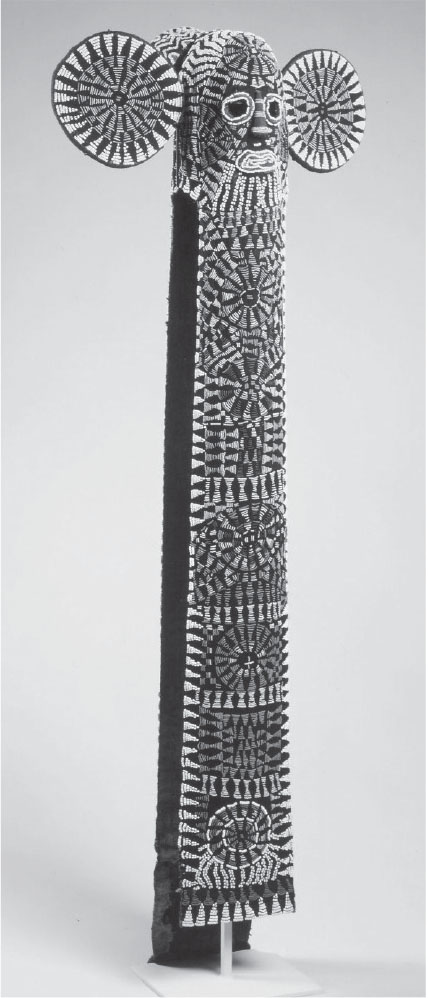

Aka elephant mask, Cameroon (western grasslands region), c. 19th to 20th century, wood, woven raffia, cloth, and beads (Figures 27.12a and 27.12b)

Figure 27.12a: Aka elephant mask, Cameroon (western grassfields region), c. 19th–20th century, wood, woven raffia, cloth, and beads

Figure 27.12b: Men wearing aka elephant masks during a ceremony

Form

■The mask has the features of an elephant: long trunk, large ears (symbolizing strength and power).

■The mask fits over the head and two folds hang down in front (symbolizing the trunk) and behind the body.

■Human face.

Materials

■Beadwork on a fabric backing; beadwork is a symbol of power.

■Lavish use of colored beads and cowrie shells displays the wealth of the members of the men’s Kuosi society; the colors and patterns express the society’s cosmic and political functions.

Function

■Elite Kuosi masking society owns and wears the masks; worn on important ceremonial occasions.

■Only important people in society can own and wear an elephant mask.

Context

■Performance art: maskers dance barefoot to a drum and gong; they wave spears and horsetails.

Content Area Africa, Image 178

Web Source www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/314264

CONTEXTUAL IMAGE

Men wearing aka elephant masks during a ceremony (Figure 27.12b)

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Spiritual World

–Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (Figures 17.4a, 17.4b)

–Staff god (Figures 28.5a, 28.5b)

–Kneeling statue of Hatshepsut (Figure 3.9b)

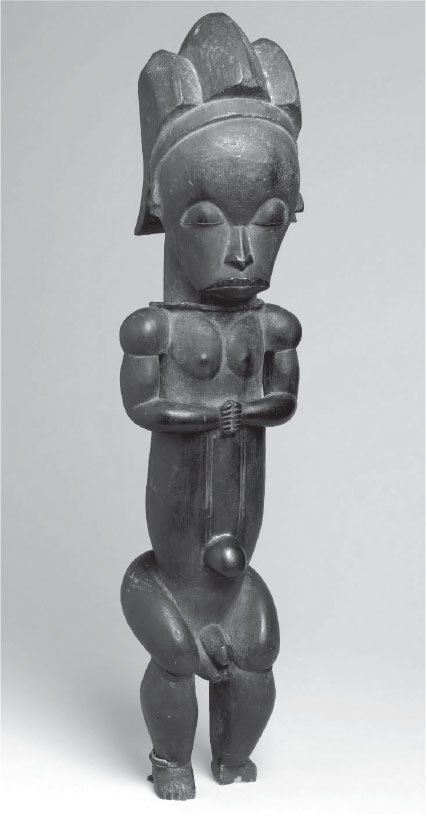

FANG

Reliquary figure (byeri), Fang peoples (southern Cameroon), c. 19th to 20th century, wood, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York (Figure 27.13)

Figure 27.13: Reliquary figure (byeri), Fang peoples (southern Cameroon), c. 19th–20th century, wood, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Form

■Feet dangling over the rim, a gesture of protecting the contents.

■Prominent belly button and genitals emphasize life; the prayerful gesture and somber look emphasize death.

■Emphasis on the head and the tubular nature of the body.

Function

■Such figures were placed on top of cylinder-like containers made of bark that held skulls and other bones of important clan leaders.

■The reliquary figure guards the head box against the gaze of women or young boys.

Context

■The surfaces were ritually rubbed with oils to add luster and protect against insects.

■Byeri figures are composed of characteristics the Fang people place a high value on: tranquility, introspection, and vitality.

■The Fang people were nomadic; these figures were made to be portable.

■The abstraction of the human body is an attraction for the early-twentieth-century artists.

Content Area Africa, Image 179

Web Source https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/4755

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Male Figure

–Apollo from Veii (Figure 5.5)

–Donatello, David (Figure 15.5)

–Nio guardian figure (Figures 25.1c, 25.1d)

YORUBA

Veranda post of enthroned king and senior wife (Opo Ogoga), Olowe of Ise (Yoruba peoples), 1910–1914, wood and pigment, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (Figure 27.14)

Figure 27.14: Veranda post of enthroned king and senior wife (Opo Ogoga), Olowe of Ise (Yoruba peoples), 1910–1914, wood and pigment, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

Form

■Wooden sculpture with tall vertical emphasis.

■Complicated and elaborate use of negative space.

■Negative space creates an openness in the composition.

■Most veranda posts were painted; this work has traces of paint remaining.

Function

■Olowe of Ise carved veranda posts for the rulers of the Ekiti-Yoruba kingdom in Nigeria.

■One of four carved for the palace at Ikere, Nigeria.

Context

■The king is the focal point between himself and others represented on the post.

■Behind the king, his large-scale senior wife supports the throne.

■She crowns the king during the coronation; protects him during his reign.

■The smaller figures include his junior wife; his flute player, Eshu, the trickster god; and a figure of a fan bearer now missing.

Content Area Africa, Image 180

Web Source http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/102611?search_no=1&index=0

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Multi-Figure Sculptures

–Helios, horses, and Dionysos (Figure 4.4)

–Rodin, The Burghers of Calais (Figure 21.15)

–King Menkaura and queen (Figure 3.7)

VOCABULARY

Adobe: a building material made from earth, straw, or clay dried in the sun (Figure 27.2)

Aka: an elephant mask of the Bamileke people of Cameroon (Figure 27.12a)

Byeri: in the art of the Fang people, a reliquary guardian figure (Figure 27.13)

Bundu: masks used by the women’s Sande society to bring girls into puberty (Figure 27.9a)

Cire perdue: the lost wax process. A bronze casting method in which a figure is modeled in clay and covered with wax and then recovered with clay. When fired in a kiln, the wax melts away, leaving a channel between the two layers of clay which can be used as a mold for liquid metal (Figure 27.3a)

Fetish: an object believed to possess magical powers

Ikenga: a shrine figure symbolizing traditional male attributes of the Igbo people (Figure 27.10)

Lukasa: a memory board used by the Luba people of central Africa (Figure 27.11)

Mblo: a commemorative portrait of the Baule people (Figure 27.7)

Ndop: a Kuba commemorative portrait of a king in an ideal state (Figure 27.5a)

Nkisi n’kondi: a Kongo power figure (Figure 27.6)

Pwo: a female mask worn by women of the Chokwe people (Figure 27.8)

Scarification: scarring of the skin in patterns by cutting with a knife: when the cut heals, a raised pattern is created, which is painted

Torons: wooden beams projecting from walls of adobe buildings (Figure 27.2)

SUMMARY

African artists operated under the same general conditions of artists everywhere—learning their craft in a period of apprenticeship, working on commission from the powerful and politically connected, and achieving a measure of international fame. However, because African artists relied on the oral tradition, little written documentation of their achievements has been recorded.

Africans achieved great distinction in the carving of masks, both in wood and metal. Costumed dancers don the mask and assume the powers of the spirit that it represents. The role of the mask, therefore, indeed the role of African art, is never merely decorative, but functional and spiritual; works are imbued with powers that are symbolically much greater than the merely visible representation.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

Questions 1–3 refer to the image below.

1.The function of the complex at Great Zimbabwe included

(A)a storehouse for grain used for dispersal in times of need

(B)a military fortress used to keep invaders out

(C)a religious center meant to represent a Christian presence in Africa

(D)a trading center with a stock and currency exchange

2.Visitors who entered Great Zimbabwe were meant

(A)to be left with the feeling that they were in a major city and transportation hub

(B)to be impressed that this was the center of manufacturing and industry

(C)to admire the impressive and extensive use of stone in a part of the world that specialized in more perishable types of construction

(D)to admire the painted friezes depicting the military exploits of the king

3.The stone walls of Great Zimbabwe exemplify the Southern African architectural practices of

(A)using ashlar masonry to create force-dependent structures

(B)making the stones from mud-backed bricks, similar to adobe construction

(C)spanning large interior spaces with great arches

(D)employing flying buttresses to support the massive walls

4.Pwo masks and Bundu masks are similar in that they both are

(A)honoring women with an idealized representation

(B)representations of an actual woman, and the rituals portray events from her life

(C)worn by women in actual ceremonies

(D)representations of the spirit of a deceased female ancestor

5.The power of Nkisi n’kondi figures is activated by

(A)nailing blades into the surface of a figure

(B)carrying a figure in a procession around a village square

(C)“marrying” the image to a second power figure

(D)masking the figure to allow its powers to work unseen

Long Essay

Practice Question 1: Comparison

Suggested Time: 35 minutes

This work is a Pwo mask from the Congo created in the early twentieth century.

Select and completely identify another work of art that was worn as a mask.

Both masks were worn in ceremonies. Describe the purpose of each ceremony.

In addition to the masks, what other materials were used in the ceremony?

Analyze how the forms of both masks were meant to enhance the meaning of the ceremony.

How do the masks differ in function?

Malagan mask

Transformation mask

Buk (mask)

ANSWER KEY

1.A

2.C

3.A

4.A

5.A

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(A) Christianity was unknown in this part of Africa at this time. Although Zimbabwe was an important trading center, the modern concept of a stock and currency exchange was unknown. Leaders controlled the food supply as a symbol of power.

2.(C) Stone buildings are rare in traditional African culture, making this complex admirable from both architectural and engineering points of view.

3.(A) No mortar is used in the construction of Great Zimbabwe; therefore, it is made of ashlar masonry.

4.(A) Both masks honor women. The Pwo mask is worn by men to honor female ancestors; the Bundu mask honors young women on the road to adulthood.

5.(A) The power figure is activated by nailing blades into the surface.

Long Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

For the Pwo mask, answers could include: |

Select and completely identify another work of art that was worn as a mask. |

— |

— |

|

Both masks were worn in ceremonies. Describe the purpose of each ceremony. |

1 point for Pwo mask |

■Female masks are used by men in ritual dances. ■Male dancers are covered with their identities masked, dressed as women with braided hair. ■It’s a ritual in which men move like women. ■The ritual depicts female ancestors. |

|

In addition to the masks, what other materials were used in the ceremony? |

1 point for Pwo mask |

■Dance. ■Music. ■Costumes. |

Analyze how the forms of both masks were meant to enhance the meaning of the ceremony. |

1 point for Pwo mask |

■Chokwe, a matriarchal society. ■It depicts female ancestors with particular characteristics: enlarged eye sockets, pushed-in chin, slender nose, high forehead, balanced features, almost-closed eyes. |

|

How do the masks differ in function? |

1 |

■Response depends on the other mask chosen. See the following. |

Task |

Point Value |

For the Malagan, Transformation, and Buk masks, answers could include: |

|

Select and completely identify another work of art that was worn as a mask. |

1; two identifiers are needed to earn a point |

Malagan mask: ■New Ireland Province of Papua New Guinea, c. 20th century, wood, figment, fiber and shell. Transformation mask: ■Kwakwaha’wakw, Northwest Coast of Canada, late 19th century, wood, paint, and string. Buk mask: ■Torres Strait, mid- to late 19th century, turtle shell, wood, fiber, feathers, and shell. |

|

Both masks were worn in ceremonies. Describe the purpose of each ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

Malagan mask: ■Malagan ceremonies send the souls of the deceased on their way to the otherworld. Transformation mask: ■Although these masks could be used at a potlatch, most often they were used in winter initiation rites ceremonies. ■Opening the mask reveals the face of an ancestor; there is an ancestral element to the ceremony. Buk mask: ■Ceremonies could involve initiation, funerary rites, and ensuring a good harvest. |

|

In addition to the masks, what other materials were used in the ceremony? |

1 point for each work |

Malagan mask: ■Dance. ■Music. ■Costumes. ■Chanting. ■Ceremonies take place in a purpose-built structure. Transformation mask: ■Drumming. ■Costumes. ■Ceremony takes place in a “big house.” Buk mask: ■Fire. ■Drumming. ■Chanting. ■Grass costumes. |

|

Analyze how the forms of both masks were meant to enhance the meaning of the ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

Malagan mask: ■Masks are extremely intricate in their carving. ■Mask indicates the relationship of a particular deceased person to a clan and to living members of the family. ■Large haircomb reflects a hairstyle of the time, but masks are not physical portraits, only portraits of the soul. ■Painted black, yellow, and red: important colors denoting violence, war, and magic. Transformation mask: ■During a ritual performance, the wearer opens and closes the transformation mask using strings. ■Bird exterior opens to reveal a human face on the interior. ■At the moment of transformation, the performer turns his back to the audience to conceal the action and heighten the mystery. Buk mask: ■Masks combine human and animal forms. ■Turtle shell is peculiar to this region and may have had symbolic overtones. ■Human face may represent a cultural hero or ancestor. |

|

How do the masks differ in function? |

1 |

Response depends on the masks chosen; however, differences can be noted in the purpose of the ceremony and therefore the mask. |