TIME PERIOD: ROCOCO: 1700–1750 AND BEYOND NEOCLASSICISM: 1750–1815

The Rococo derives its name from a combination of the French rocaille, meaning “pebble” or “shell,” and the Italian barocco, meaning “baroque.” Thus, motifs in the Rococo were thought to resemble ornate shell or pebble work.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Jefferson, Monticello)

Essential Knowledge:

■Europe and the Americas experience great innovation in economics, industrialization, war, and migration. There is a strong advancement in social issues.

■The ideas of the Enlightenment and scientific inquiry affect the arts.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction.

Essential Knowledge:

■Architecture is expressed in a series of revival styles.

■Artists are exposed to diverse, sometimes exotic, cultures as a result of colonial expansion.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Houdon, George Washington)

Essential Knowledge:

■The Salon in Paris becomes important. Museums open and display art. Art sells to an ever-widening market.

■The importance of academies rises, as artistic careers become dependent on juried salons.

■Women artists become increasingly important.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art.

Essential Knowledge:

■Artists use new media including photography, lithography, and mass production.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Wright of Derby, A Philosopher Giving a Lecture on the Orrery)

Essential Knowledge:

■Art history as a science continues to be shaped by theories, interpretations, and analyses applied to the new art forms.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Center stage in early-eighteenth-century politics was the European conquest of the rest of the world. The great struggles of the time took place among the colonial powers, who at first merely established trading stations in the lands they encountered, but later occupied distant places by layering new settlers, new languages, new religions, and new governments onto an indigenous population. At first, Europeans hoped to become wealthy by exploiting these new territories, but the cost of maintaining foreign armies soon began to outweigh the commercial benefits.

As European settlers grew wistful for home, they built Baroque- and Rococo-inspired buildings, imported Rococo fashions and garments, and made the New World seem as much like the Old World as they could.

In France, the court at Versailles began to diminish after the death of Louis XIV, leaving less power in the hands of the king and more in the nobility. Therefore, the Rococo departs from the Baroque interest in royalty, and takes on a more aristocratic flavor, particularly in the decoration of lavish townhouses that the upper class kept in Paris—not in Versailles.

The late eighteenth century was the age of the Industrial Revolution. Populations boomed as mass production, technological innovation, and medical science marched relentlessly forward. The improvements in the quality of life that the Industrial Revolution yielded were often offset by a new slavery to mechanized work and inhumane working conditions.

At the same time, Europe was being swept by a new intellectual transformation called the Enlightenment, in which philosophers and scientists based their ideas on logic and observation, rather than tradition and folk wisdom. Knowledge began to be structured in a deliberate way: Denis Diderot (1713–1784) organized and edited a massive 52-volume French encyclopedia in 1764, Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) composed the first English dictionary singlehandedly in 1755, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau discussed how a legitimate government was an expression of the general will in his 1762 Social Contract.

With all this change came political ferment—the late eighteenth century being a particularly transformational moment in European politics. Some artists, like David, were caught up in the turbulent politics of the time and advocated the sweeping societal changes that they thought the French Revolution espoused.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Rome was the place to be—to see the past. New artistic life was springing up all over Europe, leaving Rome as the custodian of inspiration and tradition, but not of progress. Italy’s seminal position as a cultural cornucopia was magnified in 1748 by the discovery of the buried city of Pompeii. Suddenly genuine Roman works were being dug up daily, and the world could admire an entire ancient city.

The discovery of Pompeii inspired art theorist Johann Winckelmann (1717–1768) to publish The History of Ancient Art in 1764, which many consider the first art history book. Winckelmann heavily criticized the waning Rococo as decadent, and celebrated the ancients for their purity of form and crispness of execution.

Because of renewed interest in studying the ancients, art academies began to spring up around Europe and in the United States. Artists were trained in what the Academy viewed as the proper classical tradition—part of that training sent many artists to Rome to study works firsthand.

The French Academy showcased selected works by its members in an annual or biannual event called the Salon, so-called because it was held in a large room, the Salon Carrè, in the Louvre. Art critics and judges would scout out the best of the current art scene, and accept a limited number of paintings for public view at the Salon. If an artist received this critical endorsement, it meant his or her prestige greatly increased, as well as the value of his paintings.

The Salons had very traditional standards, insisting on artists employing a flawless technique with emphasis on established subjects executed with conventional perspective and drawing. History paintings, that is, those paintings dealing with historical, religious, or mythological subjects, were most prized. Portraits were next in importance, followed by landscapes, genre paintings, and then still lifes.

No education was complete without a Grand Tour of Italy. Usually under the guidance of a connoisseur, the tour visited cities like Naples, Florence, Venice, and Rome. It was here that people could immerse themselves in the lessons of the ancient world and perhaps collect an antiquity or two, or buy a work from a contemporary artist under the guidance of the connoisseur. The blessings of the Neoclassical period were firmly entrenched in the mind of art professionals and educated amateurs.

ROCOCO PAINTING

Rococo painting shuns straight lines, even in the frames of paintings. It is typical to have curved frames with delicate rounded forms in which the limbs of several of the figures spill over the sides so that the viewer is hard-pressed to determine what is painted and what is sculpted.

Rococo art is flagrantly erotic, sensual in its appeal to the viewer. The curvilinear characteristics of Rococo paintings enhance their seductiveness. Unlike the sensual paintings of the Venetian Renaissance, these paintings tease the imagination by presenting playful scenes of love and romance with overt sexual overtones.

Although the French are most noted for the Rococo, there were also active centers in England, central Europe, and Venice.

Rococo painting is the triumph of the Rubénistes over the Poussinistes. Artists, particularly those of Flemish descent like Watteau, were captivated by Rubens’s use of color to create form and modeling.

Figures in Rococo painting are slender, often seen from the back. Their light frames are clothed in shimmering fabrics worn in bucolic settings like park benches or downy meadows. Gardens are rich with plant life and flowers dominate. Figures walk easily through forested glens and flowery copses, contributing to a feeling of oneness with nature reminiscent of the Arcadian paintings of the Venetian Renaissance. Fête galante painting features the aristocracy taking long walks or listening to sentimental love songs in garden settings.

Colors are never thick or richly painted; instead, pastel hues dominate. Some artists specialized in pastel paintings that possessed an extraordinary lifelike quality. Others transferred the spontaneous brushwork and light palette of pastels to oils.

By and large, Rococo art is more domestic than Baroque, meaning it is more for private rather than public display.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767, oil on canvas, Wallace Collection, London (Figure 19.1)

Form

■Pastel palette; light brushwork.

■Figures are small in a dominant garden-like setting.

■Use of atmospheric perspective.

■Puffy clouds; rich vegetation; abundant flowers; sinuous curves.

■Symbolically a dreamlike setting.

Patronage and Content

■Commissioned by an unnamed “gentleman of the Court:” a painting of his young mistress on a swing; in an early version, a bishop is pushing the swing with the gentleman admiring his mistress’s legs from below.

■In the finished painting, the older man is no longer a priest, a barking dog has been added, and Falconet’s sculpture of Menacing Love comments on the story.

■The patron in the lower left looks up the skirt of a young lady who swings flirtatiously, boldly kicking off her shoe at a sculpture.

■The dog in the lower right corner, generally seen as a symbol of fidelity, barks in disapproval at the scene before him.

Figure 19.1: Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767, oil on canvas, Wallace Collection, London

Context

■Fragonard answers the libertine intentions of his patron by painting in the Rococo style.

■Fragonard often used different styles at the same time, and he seems to have seen the Rococo as particularly appropriate for an erotic scene.

■An intrigue painting; the patron hides in a bower; the garden sculpture of Menacing Love asks the lady to be discreet and may be a symbol for the secret hiding of the patron.

Content Area Later Europe and Americas, Image 101

Web Source https://www.wallacecollection.org/collection/les-hazards-heureux-de-lescarpolette-swing/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Figures Set in a Landscape

–Fan Kuan, Travelers among Mountains and Streams (Figure 24.5)

–Dürer, Adam and Eve (Figure 14.3)

–Cotsiogo, Hide Painting of a Sun Dance (Figure 26.13)

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait, 1790, oil on canvas, Uffizi, Florence (Figure 19.2)

Form

■Light Rococo touch in the coloring.

■Inspired by the portraits of Rubens.

Context

■Forty self-portraits exist, all highly idealized.

■The artist was 45 when this was painted, but she appears much younger.

■Painted in Rome during the French Revolution when the artist was exiled for political reasons.

■The artist was granted admission to the male-dominated French Royal Academy through the influence of Marie Antoinette.

■The artist looks at the viewer as she paints a portrait of the French queen Marie Antoinette, who is rendered from memory since she was killed during the French Revolution.

■Subject in the painting looks admiringly upon the painter.

Content Area Later Europe and Americas, Image 105

Web Source https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005721740

Figure 19.2: Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait, 1790, oil on canvas, Uffizi, Florence

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Individual, Status, and Society

–Augustus of Prima Porta (Figure 6.15)

–Portrait of Sin Sukju (Figure 24.6)

–Mblo (Figure 27.7)

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH PAINTING

Freedom of expression swept through France and England at the beginning of the eighteenth century and found its fullest expression in the satires of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and Voltaire’s Candide. The visual arts responded by painting the first overt satires, the most famous of which are by the English painter Hogarth. Satirical paintings usually were done in a series to help spell out a story as in Marriage à la Mode (Figure 19.3). Afterward the paintings were transferred to prints, so that the message could be mass produced. Themes stem from exposing political corruption to spoofs on contemporary lifestyles. Hogarth knew that the pictorial would reach more people than the written, and he hoped to use his prints to didactically expose his audience to abuses in the upper class. Society had changed so much that by now those in power grew more tolerant of criticism so as to allow satirical painting to flourish, at least in England. Today, the political cartoon is the descendant of these satirical prints.

William Hogarth, The Tête à Tête from Marriage à la Mode, c. 1743, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London (Figure 19.3)

Marriage à la Mode

Form

■Richly decorated rooms painted in brilliant color.

■Myriad of details; each detail adds to the symbolism in the work.

■Elements of French Rococo style used to indict those who are flattered in French art.

Figure 19.3: William Hogarth, The Tête à Tête from Marriage à la Mode, c. 1743, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London

Function

■Highly satiric paintings about a decadent English aristocracy and those who would have liked to buy their way into it.

■A series of six narrative paintings; later turned into a series of prints.

Context

■Second of six scenes in a suite of paintings called Marriage à la Mode.

The Tête-à-Tête

■Shortly after the marriage each partner has been pursing pleasures without the other.

■The husband has been out all night with another woman (the dog sniffs suspiciously at another bonnet); the broken sword means he has been in a fight and probably lost (and may also be a symbol for sexual inadequacy).

■The wife has been playing cards all night, the steward indicating by his expression that she has lost a fortune at a card game called whist; he holds nine unpaid bills in his hand (one was paid by mistake, further illustrating their carelessness).

■The painting over the mantlepiece is a symbolic depiction of Cupid among the ruins.

■A turned-over chair indicates that the violin player made a hasty retreat when the husband came home.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 98

Web Source http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/william-hogarth-marriage-a-la-mode-2-the-tete-a-tete

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Elements of Humor

–Jeff Koons, Pink Panther (Figure 29.9)

–Michel Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000) (Figure 29.16)

–Honoré Daumier, Nadar Raising Photography to the Height of Art (Figure 21.2)

Joseph Wright of Derby, A Philosopher Giving a Lecture on the Orrery, 1763–1765, oil on canvas, Derby Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, U.K. (Figure 19.4)

Form

■One of a series of candlelight pictures by Wright; inspired by Caravaggio’s use of tenebrism.

■Clearly drawn and sharply delineated portraits of individuals.

Figure 19.4: Joseph Wright of Derby, A Philosopher Giving a Lecture on the Orrery, 1763–1765, oil on canvas, Derby Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, U.K.

Content

■An orrery is an early form of a planetarium, imitating the motion of the solar system.

■The lamp in the center represents the sun; it is blocked by the silhouette of a figure.

■All ages of man are represented by the mixed group of middle-class people in attendance.

■Some curious, some contemplative, some in wonder, some fascinated.

■The philosopher is based loosely on a portrait of Isaac Newton; he is demonstrating an eclipse.

■The philosopher stops to clarify a point for the note-taker on the left.

Context

■Influenced by a provincial group of intellectuals called the Lunar Society, who met once a month to discuss current scientific discoveries and developments.

■To complete the celestial theme, each face in the painting is an aspect of the phases of the moon.

■Illustrates the eighteenth-century period called the Enlightenment and the democratization of knowledge.

Content Area Later Europe and Americas, Image 100

Web Source http://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/jom/0706/byko-0706.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Knowledge

–Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings (Figure 23.9)

–Cabrera, Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Figure 18.6)

NEOCLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE

The best Neoclassical buildings were not dry adaptations of the rules of ancient architecture, but a clever revision of classical principles onto a modern framework. While many buildings had the outward trappings of Roman works, they were also efficiently tailored to living in the eighteenth century.

Ancient architecture came to Europe distilled through the books written by the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, and reemphasized by the classicizing works of Inigo Jones. From these sources Neoclassicists learned about symmetry, balance, composition, and order. Greek and Roman columns, with their appropriate capitals, appeared on the façades of most great houses of the period, even in the remote hills of Virginia. Pediments crown entrances and top windows. Domes grace the center of homes, often setting off gallery space. The interior layout is nearly or completely symmetrical, with rectangular rooms mirroring one another on either side of the building. Each room is decorated with a different theme, some inspired by the ancient world, others with a dominant color in wallpaper or paint.

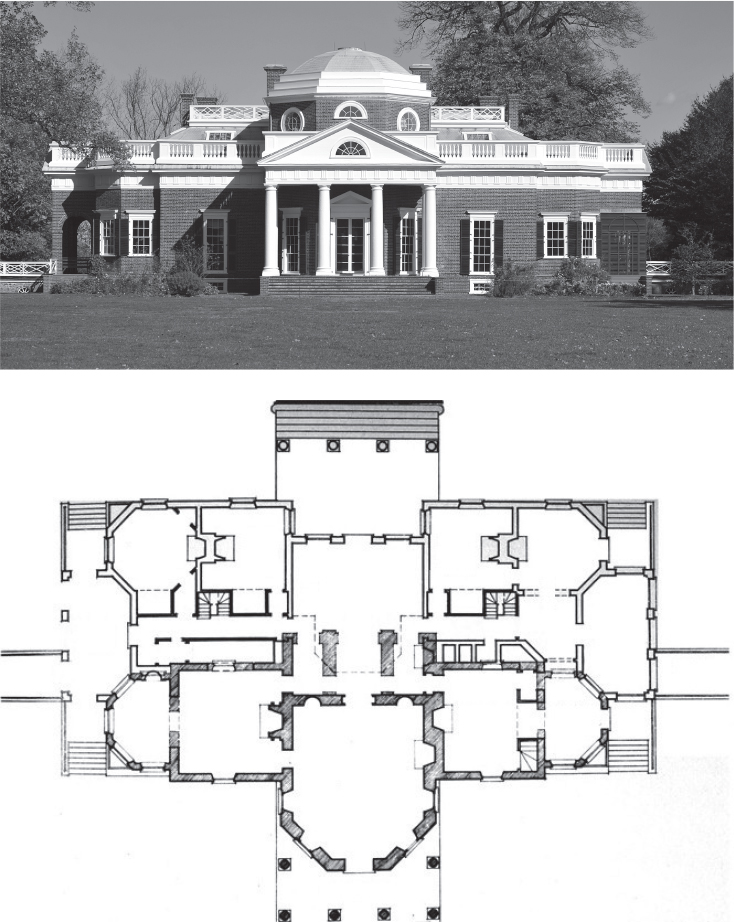

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello, 1768–1809, brick, glass, stone, and wood, Charlottesville, Virginia (Figures 19.5a and 19.5b)

Form

■Monticello is a brick building with stucco applied to the trim to give the effect of marble.

■It appears to be a one-story building with a dome, but the balustrade hides a modest second floor.

■The octagonal dome functions as an office or retreat.

■The rooms generally have a symmetrical design.

■Tall French doors and windows allow air circulation in hot Virginia summers.

■Jefferson was concerned with saving space: very narrow spiral staircases; beds in alcoves or in walls between rooms.

Figures 19.5a and 19.5b: Thomas Jefferson, Monticello, 1768–1809, brick, glass, stone, and wood, Charlottesville, Virginia

Function

■Chief building on Jefferson’s plantation, supported by slave labor.

Context

■Monticello is “little mountain” in Italian, sited on a hilltop in Virginia.

■Inspired by books by the Italian Renaissance architect Palladio and by Roman ruins Jefferson saw in France.

■The design is also impacted by eighteenth-century French buildings in Paris.

■Illustrates the Roman Republican goals of equality and democracy expressed in this adaptation of Roman architectural themes.

Content Area Later Europe and Americas, Image 102

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/442/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Classical Revival

–Houdon, George Washington (Figure 19.7)

–Donatello, David (Figure 15.5)

–Alberti, Palazzo Rucellai (Figure 15.2)

NEOCLASSICAL PAINTING

Stories from the great epics of antiquity spoke meaningfully to eighteenth-century painters. Mythological or Biblical scenes were painted with a modern context in mind. The retelling of the story of the Horatii would be a dry academic exercise if it did not have the added implication of self-sacrifice for the greater good. A painting like this was called an exemplum virtutis.

Even paintings that did not have mythological references had subtexts inviting the viewer to take measure of a person, a situation, and a state of affairs.

Compositions in Neoclassical paintings were symmetrical, with linear perspective leading the eye into a carefully constructed background. The most exemplary works were marked by invisible brushwork and clarity of detail.

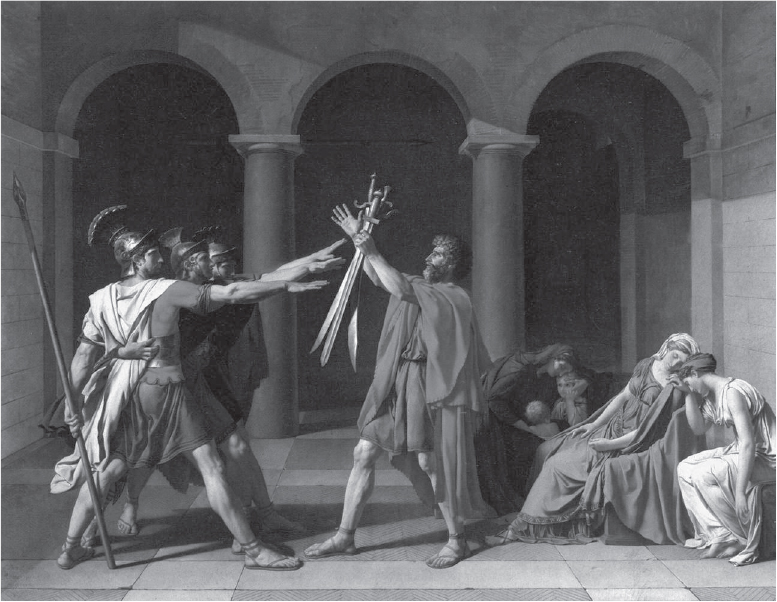

Jacques-Louis David, The Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris (Figure 19.6)

Form

■Male forms are vigorous, powerful, animated, emphatic, angular; symbolically they are figures of action.

■Female forms are soft and rounded, displaying “feminine” emotion; symbolically they are figures of inaction or reaction.

■Gestures are sweeping and unified.

■Figures are pushed to the foreground.

■Neoclassical drapery and tripartite composition.

■Not neoclassical in its Caravaggio-like lighting and un-Roman architectural capitals.

Figure 19.6: Jacques-Louis David, The Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris

Patronage

■Painted under royal patronage, Louis XVI.

■The artist presented the finished canvas in his studio in Rome in 1785 and at the Paris Salon later that year—on both occasions to acclaim.

Content

■Story of three Roman brothers (the Horatii) who do battle with three other brothers (the Curiatii—not painted) from the nearby city of Alba; they pledge their fidelity to their father and to Rome.

■One of the three women on right is a Horatii engaged to one of the Curiatii brothers; another woman is the sister of the Curiatii brothers and wife of the eldest Horatii.

Context

■Exemplum virtutis.

■David presents this episode as an example of patriotism and stoicism, which should override family relationships.

■Influenced by Enlightenment philosophers, such as Diderot, who advocated the painting of moral subjects.

■Emulated Grand Style of French painting of the seventeenth century.

Content Area Later Europe and Americas, Image 103

Web Source http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/oath-horatii

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Historicism

–Rivera, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park (Figure 22.20)

–Shonibare, The Swing (after Fragonard) (Figure 29.22)

–Sherman, Untitled #228 (Figure 29.10)

NEOCLASSICAL SCULPTURE

Before the Industrial Revolution, bronze was the most expensive and most highly prized sculptural medium. Mass production of metal made possible by factories in England and Germany caused the price of bronze to fall, while simultaneously causing the price of marble to rise. Stonework relied on manual labor, a cost that was now going up. Because it was felt that the ancients preferred marble, it still seemed more desirable possessing an authoritative appeal. It was also assumed that the ancients preferred an unpainted sculpture, because the majority of marbles that have come down to us have lost their color.

The recovery of artifacts from Pompeii increasingly inspired sculptors to work in the classical medium. This reached a fever pitch with the importation of the Parthenon sculptures, the Elgin Marbles, to London, where they were eventually purchased by the state and ensconced in the Neoclassical British Museum. Sculptors like Houdon saw the Neoclassical style as a continuance of an ancient tradition.

Sculpture, while deeply affected by classicism, also was mindful of the realistic likeness of the sitter. Sculptors moved away from figures wrapped in ancient robes to more realistic figural poses in contemporary drapery. Classical allusions were secondary influences. Still, Neoclassical sculpture was carved from white marble with no paint added, the way it was felt the ancients worked.

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–1792, marble, State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia (Figure 19.7)

Form and Content

■Washington is dressed as an eighteenth-century gentleman with a Revolutionary War uniform.

■Military associations minimized: he wears only epaulettes on his shoulders; the sword is cast to the side.

■Naturalistic details: the missing button on his jacket and the tightly buttoned vest around a protruding stomach.

■Seen as a man of vision and enlightenment.

■Stance inspired by Polykleitos’s Doryphoros (Figure 4.3) linking Washington’s actions with the greatness of the past.

Materials

■Marble, appreciated for its durability and luster, was used to associate the figure of Washington with the great sculptures of the Renaissance and the ancient world.

Figure 19.7: Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–1792, marble, State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia

Function and Patronage

■Commissioned by the Virginia legislature to stand at the center of the state capitol in Richmond, which was designed by Jefferson.

■Meant to commemorate the central position of Washington in the founding of American independence.

■Installed in 1796, the year Washington published his farewell address.

Symbolism

■The badge of Cincinnatus is on his belt: Washington was a gentleman-farmer who left Mount Vernon to take up the American cause much as Cincinnatus from the Roman Republic left his farm to command Roman armies and then returned to the farm.

■Washington leans on the Roman fasces: a group of rods bound together on the top and the bottom; the 13 rods symbolize the 13 colonies united in a cause.

■Washington leans on the 13 colonies, from which he gets his support.

■Arrows between the rods likely refer to Native Americans or the idea of America as wild frontier.

■Plow behind Washington symbolizes his plantation as well as the planting of a new world order.

Content Area Later Europe and Americas, Image 104

Web Source https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/online_classroom/shaping_the_constitution/doc/washington

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Rulers

–King Menkaura and queen (Figure 3.7)

–Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene (Figure 28.7)

–Augustus of Prima Porta (Figure 6.15)

VOCABULARY

Academy: an institution whose main objectives include training artists in an academic tradition, ennobling the profession, and holding exhibitions

Exemplum virtutis: a painting that tells a moral tale for the viewer (Figure 19.6)

Fête galante: an eighteenth-century French style of painting that depicts the aristocracy walking through a forested landscape

Grand Tour: in order to complete their education young Englishmen and Americans in the eighteenth century undertook a journey to Italy to absorb ancient and Renaissance sites

Pastel: a colored chalk that when mixed with other ingredients produces a medium that has a soft and delicate hue

Salon: a government-sponsored exhibition of artworks held in Paris in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

SUMMARY

The early eighteenth century saw the shift of power turn away from the king and his court at Versailles to the nobles in Paris. The royal imagery and rich coloring of Baroque painting was correspondingly replaced by lighter pastels and a theatrical flair. Fragonard’s lighthearted compositions, called fête galantes, were symbolic of the aristocratic taste of the period.

Partly inspired by the French Rococo, English painters and patrons delighted in satirical painting, reflecting a more relaxed attitude in the eighteenth century toward criticism and censorship.

The aristocratic associations of the Rococo caused the style to be reviled by the Neoclassicists of the next generation, who thought that the Rococo style was decadent and amoral. Even so, the Rococo continued to be the dominant style in territories occupied by Europeans in other parts of the world—there it symbolized a cultured and refined view of the world in the midst of perceived pagans.

Intellectuals influenced by the Enlightenment were quick to reject the Rococo as decadent, and espoused Neoclassicism as a movement that expressed the “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” of the French Revolution. Moreover, the discovery of Pompeii and the writings of Johann Winckelmann, the first art historian, did much to revive interest in the classics and use them as models for the modern experience.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard is similar to other Rococo paintings in that it

(A)uses tenebrism to sharply contrast dark and light

(B)is concerned with the classical ideals of Polykleitos

(C)is innovative and experimental in painting techniques

(D)uses a pastel palette

2.The structure of Monticello is heavily influenced by Thomas Jefferson’s

(A)trip to Spain to study Renaissance architecture

(B)work as an archaeologist uncovering the ancient ruins of Pompeii

(C)study of books on architecture by the Italian architect Palladio

(D)friendship with George Washington, whose architectural theories were widely respected

3.The columns and the pediment of Monticello are meant to recall the

(A)ancient Egyptian pharaohs and their expression of eternity

(B)Greek gods and their mythological stories

(C)Roman Republic and its governmental ideals

(D)Gothic churches and their spirituality

4.Jacques-Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii is based on an ancient Roman story, but the painting technique owes a great deal to

(A)Peter Paul Rubens

(B)Caravaggio

(C)Johannes Vermeer

(D)Jacopo Pontormo

5.William Hogarth’s satiric paintings are a reflection of a movement in the eighteenth century called

(A)the Enlightenment

(B)Naturalism

(C)the Industrial Revolution

(D)the Grand Tour

Short Essay

Practice Question 5: Attribution

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

Attribute this painting to the artist who painted it.

Using at least two specific details, justify your attribution by describing relevant similarities between this work and a work in the required course content.

Using at least two specific details, explain why these visual elements are characteristic of this artist.

ANSWER KEY

1.D

2.C

3.C

4.B

5.A

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(D) Rococo paintings can be characterized by their soft, delicate, pastel color schemes.

2.(C) Jefferson possessed copies of Palladio’s books on architecture.

3.(C) Jefferson felt that the Roman Republic embodied the spirit of democracy.

4.(B) The dark/light contrast called tenebrism is associated with artists like Caravaggio. David’s mysteriously darkened background in The Oath of the Horatii is indebted to this artist.

5.(A) European painting was affected by the Enlightenment. For the first time, artists experienced a new freedom to lampoon political and social conventions in a public way. All the other choices are events that took place in the eighteenth century but don’t apply to this question.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Attribute this painting to the artist who painted it. |

1 |

Jacques-Louis David |

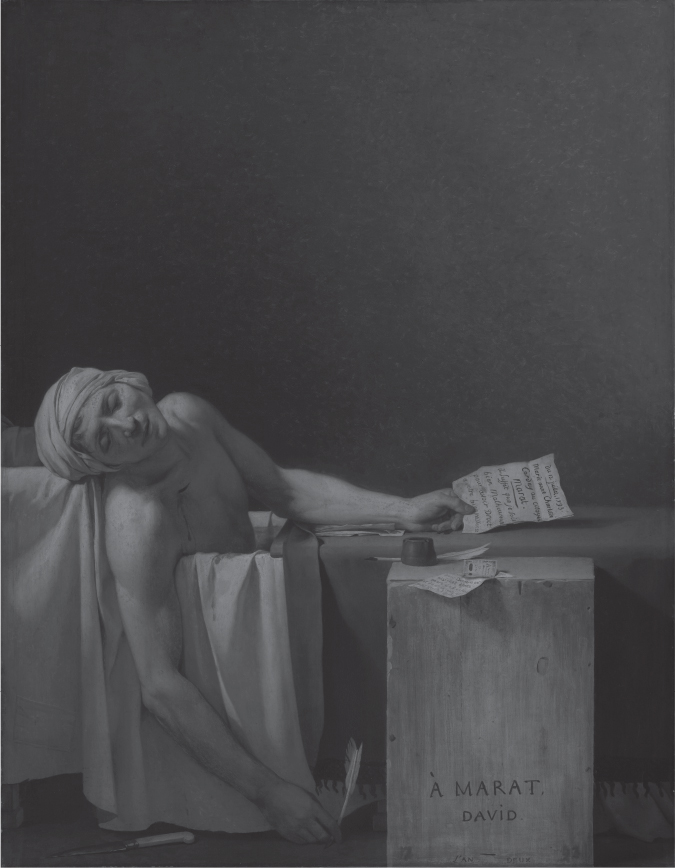

Using at least two specific details, justify your attribution by describing relevant similarities between this work and a work in the required course content. |

2 |

The work in the required course content is David, The Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, Neoclassicism. Two specific details could include: ■Greco-Roman imagery. ■Classical compositions. ■Antique drapery. ■Firm, robust, idealized figures. ■Minimum of extraneous detail. ■Tenebrism. |

Using at least two specific details, explain why these visual elements are characteristic of this artist. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■David was an advocate of the French Revolution, which was seen as a mythical and critical moment in politics. ■David used the ancient world to reflect on the contemporary world. ■David’s style of Neoclassicism was a rejection of the previous Rococo style, which was linked to the aristocracy. ■Both works indicate a dedication to patriotic causes. |