Content Area: South, East, and Southeast Asia, 300 B.C.E.–1980 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: FROM PREHISTORIC TIMES TO THE PRESENT

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Terra cotta warriors)

Essential Knowledge:

■The art of China is some of the oldest in the world with the longest continuous tradition.

■Chinese artists employ a wide range of materials including ceramics and metal.

■Distinctive to China is the development of monochrome ink painting and the pagoda.

■Chinese art extensively employs stone and wood carving.

■Calligraphy was considered the highest art form in China.

■Silk weaving is an important Chinese art form.

■Elaborate floral and animal-inspired artwork is a Chinese specialty.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Funeral banner of Lady Dai)

Essential Knowledge:

■Ancient Chinese civilizations were very advanced for their time.

■Shared cultural ideas throughout Asia stimulated artistic production.

■Some of the world’s greatest philosophies and religions developed in China.

■Figural subjects are common in Chinese painting.

■Daoism and Confucianism, both Chinese philosophies, explore the interconnected nature that people have with the spiritual and natural world.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan)

Essential Knowledge:

■Chinese art featured a counterculture approach called the literati.

■Chinese architecture is generally religious.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Longmen Caves)

Essential Knowledge:

■Asian art is influenced by global trends, and in turn influences global trends.

■Trade routes connected Asia with the world.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Gold and jade crown)

Essential Knowledge:

■Art history as a science is subject to differing interpretations and theories that change over time.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Although Chinese culture seems monolithic to those in the West, China has the size and population of Europe, with the same ethnic diversity and the same number of languages. To speak in general terms of Chinese art, therefore, has the same validity as speaking in general terms about European art.

To make such a diverse subject more manageable, Chinese art is divided into historical periods named after the families who ruled China for vast stretches of time. These families, united by blood and tradition, formed dynasties, and their impact on Chinese culture has been enormous.

The first ruler of a united China was Emperor Shi Huangdi, who reigned in the third century B.C.E. He not only unified China politically, but was also responsible for codifying written Chinese, standardizing weights and measures, and establishing a uniform currency. Moreover, he started the famous Great Wall and began his majestic tomb. While historians have taken a more critical look at Shi Huangdi’s accomplishments, his insistence on government promotion based on achievement rather than family connections had far-reaching effects on Chinese society.

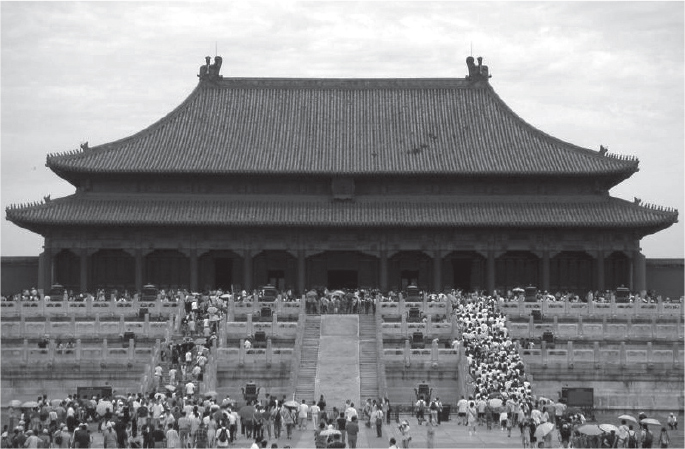

Dynastic fortunes reached their greatest height during the Tang Dynasty (618–906 C.E.). Brilliant periods were also achieved under the Yuan of Kublai Khan (1215–1294) and the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), which built the Forbidden City (Figure 24.2).

A particularly long-lasting and artistically rich period in Korea was formed during the Silla Dynasty (57 B.C.E.–935 C.E.). Silla rulers united with the Tang Dynasty to solidify territorial gains on the Korean peninsula. They later waged a successful war to expel the Chinese who had intended to form puppet governments throughout Korea. Silla rulers established a royal burial ground in present-day Gyeongju. The largest tomb measures over 260 feet in diameter and 400 feet long, and contains a wide array of imperial gold regalia, jewelry, pottery, and metalwork.

East Asia has been marked by a great deal of turbulence in the twentieth century. The Qing Dynasty collapsed in 1911, replaced by a chaotic rule under the Republic of China. The Japanese invasion in the 1930s caused more upheaval, as did the eventual triumph of the communist forces under Mao Tse-tung in 1949. Peace still did not settle over China since internal struggles, such as the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward, ended up being political motives to enforce purges and persecutions.

Similarly in Korea, occupation by Japan left great scars on the Korean physical and mental landscape. The 1945 Japanese collapse left Korea as a nation divided in two. The subsequent Korean War achieved little—the country lay in ruins, and is still divided roughly the same way it was before the war. Today South Korea has a vibrant economy and is a world leader in many scientific and economic related fields. North Korea, however, remains economically stagnant.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Calligraphy is the central artistic expression in traditional China, standing as it does at a midpoint between poetry and painting. Those who wanted important state positions had to pass a battery of exams that included calligraphy. Even emperors were known to have been accomplished calligraphers, painters, and poets. Standard written Chinese is often at variance with the more cursive or running script used in paintings, some of which is so artistically rendered that modern Chinese readers cannot decipher it. Rather than letters, which are used in European languages, Chinese employs characters, each of which represents a word or an idea. Therefore, the artistic representation of a word inherently carries more meaning than a creatively written individual letter in English.

Artists worked under the patronage of religion or the state, although a counterculture was developed by a group called the literati who painted for themselves, eschewing public commissions and personal fame. These artists produced paintings of a highly individualized nature, not caring what the world at large would think.

At first the Korean language was written with adapted Chinese characters called hanja. A native alphabet was invented in 1444 during the reign of Kong Sejong, a king of the Joseon Dynasty. However, many Koreans preferred to remain loyal to the Chinese script, seeing the native writing as common and therefore for the uneducated. During the twentieth century, standard Korean began to adopt the native script as its own. Today, it is more likely to be written in a western style—that is, horizontally and from left to right—in contrast to other Asian scripts.

CHINESE PHILOSOPHIES

Daoism and Confucianism, the two great philosophies of ancient China, dominate all aspects of Chinese art, from the original artistic thought to the final execution. Dao, meaning “the Way,” can be characterized as a religious journey that allows the pilgrim to wander meaningfully in search of self-expression. It was begun by Laozi (604–531 B.C.E.), a philosopher who believed in escaping society’s pressures, achieving serenity, and working toward a oneness with nature. Daoists emphasize individual expression and strongly embrace the philosophy of doing unto others. The yin and the yang are well-known Daoist symbols (Figure 24.3c).

The great Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 B.C.E.) wrote about behavior, relationships, and duty in a series of precepts called The Analects. Built on a system of mutual respect, the Confucian model presents an ideal man whose attributes include loyalty, morality, generosity, and humanity. An important ingredient in Confucianism is respect for traditional values.

CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

The design of the stupa, a Buddhist building associated with India, moved eastward with missionaries along the Great Silk Road, transforming itself into the pagoda when it reached China. Built for a sacred purpose, the pagoda characteristically has one design that is repeated vertically on each level, each smaller than the design below it. In this way, pagodas achieve substantial height through a repetition of forms.

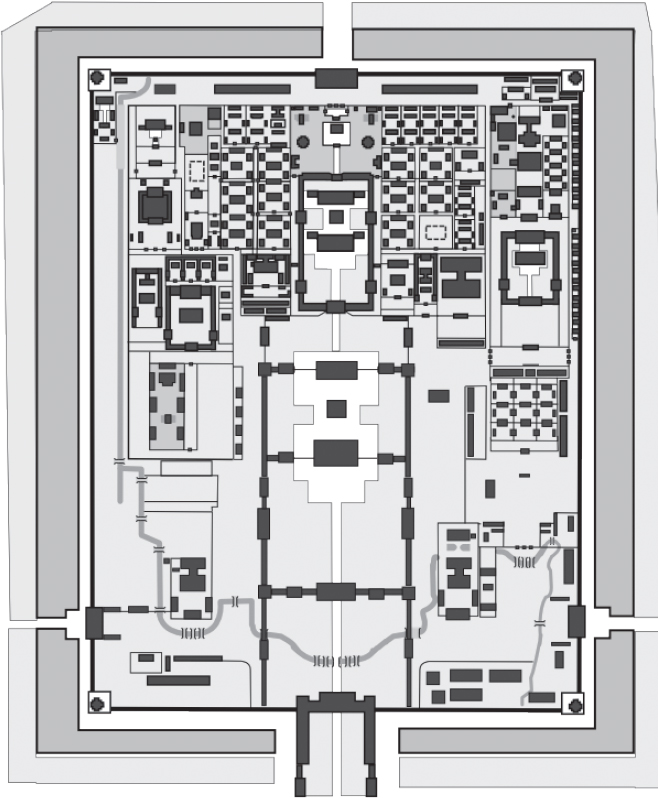

The exterior walls of a courtyard style residence (Figure 24.1) kept the crowded outside world away and framed an atrium in which family members resided in comparative tranquility. In harmony with Confucian thought, elders were to be honored and so were to live in a suite of rooms on the warmer north end of the courtyard. Children lived in the wings, servants in the south end. The southeast corner usually functioned as an entrance, and the southwest as a lavatory.

This courtyard-style arrangement is reflected on a massive scale in the Forbidden City. The emperor’s seat is in the Hall of Supreme Harmony, itself on the north end of a courtyard; the throne faces south. The entire Forbidden City is a rectangular grid with its southern entrance and its high walls keeping the concerns of the multitude at a safe distance.

The Chinese, both in the Forbidden City and in less lavish projects, used wood for their principal building material. Tiled roofs seem to float over structures with eaves that hang away from the wall space and curve up to allow light in and keep rain out. Walls protect the interior from the weather, but do not support the building. Instead, support comes from an interior fabric of wooden columns that are grooved together rather than nailed. Corbeled brackets are used to transition the tops of columns to the swinging eaves. Wooden architecture is painted both to preserve the wood and enhance artistic effect.

Figure 24.1: Chinese courtyard-style residence with the principal structure on the north side facing south.

Forbidden City, 15th century and later, Ming Dynasty, stone masonry, marble, brick, wood, ceramic tile, Beijing, China (Figures 24.2a, 24.2b, 24.2c, 24.2d)

Form

■Largest and most complete Chinese architectural ensemble in existence.

■9,000 rooms.

■Walls were built 30 feet high to keep outside people out and those inside in.

■Each corner of the rectangular plan has a tower representing one of the four corners of the world.

■The focus is on the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the throne room and seat of power; it is a wooden structure made with elaborately painted beams; meant for grand ceremonies.

■Yellow tile roofs and red painted wooden beams placed on marble foundations unify the structures in the Forbidden City into an artistic whole; yellow is the emperor’s color.

Figure 24.2a: Forbidden City, 15th century and later, stone masonry, marble, brick, wood, and ceramic tile, Beijing, China

Function

■The emperor’s palace; the seat of Chinese power: the capital of the empire during the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

■Originally built to consolidate the emperor’s power.

■Ceremonies took place in the Hall of Supreme Harmony for the new year, the winter solstice, and the emperor’s birthday.

■The Hall of Supreme Harmony is the largest building in the complex.

Figure 24.2b: Front Gate of the Forbidden City

Context

■Called “Forbidden” in that no one could enter or leave the inner sanctuaries without official permission.

■The throne room was placed symbolically at the center.

■The emperor is associated with the dragon: sits on a dragon throne, wears dragon-themed robes.

■Animals and figures on the roof were placed to ward off fire and evil spirits.

■The surrounding wall of the Forbidden City is characteristic of a Chinese city: privacy within provides protection and reflects the containment aspect of Chinese culture.

■Mandate of Heaven: heaven bestows a mandate on the emperor, who rules with divine blessing as the Son of Heaven; as a result, his Forbidden City was a reflection of heaven itself.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 206

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/439

Figure 24.2c: Hall of Supreme Harmony

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Centers of Power

–Versailles (Figure 17.3a)

–Nan Madol (Figures 28.1a, 28.1b)

–Barry and Pugin, Houses of Parliament (Figures 20.1a, 20.1b)

Figure 24.2d: Plan of Forbidden City

CHINESE AND KOREAN PAINTING

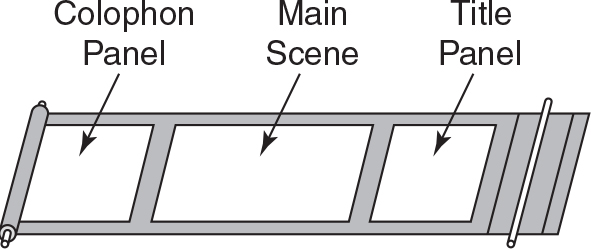

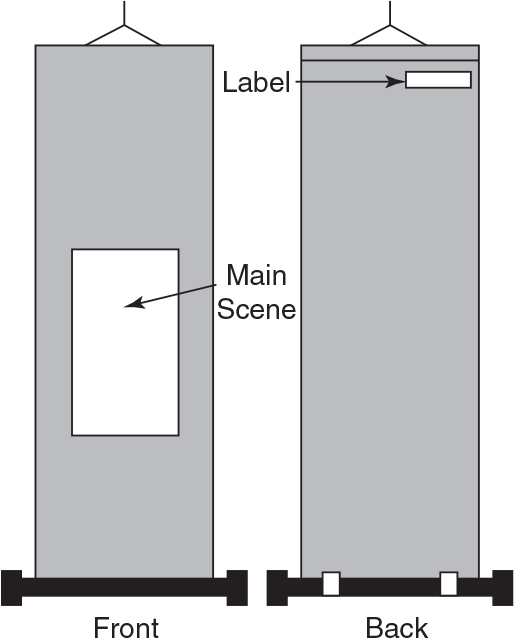

East Asian painting appears in many formats, including album leaves, fans, murals, and scrolls. Scrolls come in two formats: The handscroll (Figure 24.3a), which is horizontal and can be read on a desk or table, and the hanging scroll (Figure 24.3b), which is supported by a pole or hung for a time on a wall and unraveled vertically. No scrolls were allowed on permanent view in a home—they were something to be admired, studied, and analyzed, not hung for mere decorative qualities. Scrolls were stored away in specifically designed cabinets.

Figure 24.3a: A Chinese handscroll read right to left. It starts with the title panel, moves to the main scene, and ends with a colophon.

Handscrolls are read right to left. Although paper is sometimes used as a painting surface, silks are preferred and specially chosen by the artist for their color and texture to evoke a mood. The silk is then attached to wooden dowels and secured at the ends. When the scrolls are unwound, a title panel first appears, much like the title page in a book. As the scroll is carefully unrolled a section at a time, the viewer encounters both text and painting intertwined. Square red markings, made by artistically rendered seals, identify either the artist or the owners of the painting. In Chinese art, it is considered acceptable to comment on a work by writing poetry in praise of what has been read or seen. The commentaries are written on the last panel, called the colophon.

Figure 24.3b: A Chinese hanging scroll with the main scene on the front and the title on the top back.

Landscape paintings are highly prized in Chinese art. Like European paintings of the same date, they do not seek to represent a particular forest or mountain, but reflect an artistic construct yielding a philosophical idea. Typically, some parts of a painting are empty and barren, suggesting openness and space. Other parts are crowded, almost impenetrable. This intertwining of crowded and empty spaces is a reflection of the Daoist theory of yin and yang (Figure 24.3c), in which opposites flow into one another.

Figure 24.3c: Yin and yang

Another specialty is porcelain. Subtle and refined vase shapes are combined with imaginative designs to create works of art that appear to be utilitarian, but are actually objects that stand alone. To achieve maximum gloss and finish, sophisticated glazing techniques are applied to the surface. Glazing has the added benefit of protecting the vase from wear.

The Literati

Some artists rejected the restrictive nature of court art and developed a highly individualized style. These artists, called literati, worked as painters, furniture makers, and landscape architects, as well as in other fields. The literati were often scholars rather than professional artists, and by tradition did not sell their works, but gave them to friends and connoisseurs.

Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), Han Dynasty, 180 B.C.E., painted silk, Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha (Figure 24.4)

Form and Content

■Painted in three distinct sections:

–Top: Heaven, with the crescent moon at left and the legend of the ten suns at right.

•In the center, two seated officers guard the entrance to the heavenly world.

–Middle: Earth, with Lady Dai in the center on a white platform about to make her journey to heaven with the walking stick that was found in her tomb.

•Mourners and assistants appear by her side.

•Dragons’ bodies are symbolically circled through a bi in a yin and yang exchange.

–Bottom: the underworld; symbolically low creatures frame the underworld scene: fish, turtles, dragon tails; tomb guardians protect the body.

Figure 24.4: Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), Han Dynasty, 180 B.C.E., painted silk, Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha

Function

■The T-shaped silk banner covered the inner coffin which contained the intact body of Lady Dai in a tomb.

■It was probably carried in a procession to the tomb, and then placed over the body to speed its journey to the afterlife.

Context

■Lady Dai died in 168 B.C.E. in the Hunan province during the Han Dynasty.

■The tomb found with more than 100 objects in 1972.

■Yin symbols on the left of the banner; Yang symbols at right; the center mixes the two philosophies; Daoist elements.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 194

Web Source http://61.187.53.122/collection.aspx?id=1348&lang=en

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Fabric Arts

–Hiapo (Figure 28.6)

–All-T’oqapu tunic (Figure 26.10)

–Ringgold, Dancing at the Louvre (Figure 29.11)

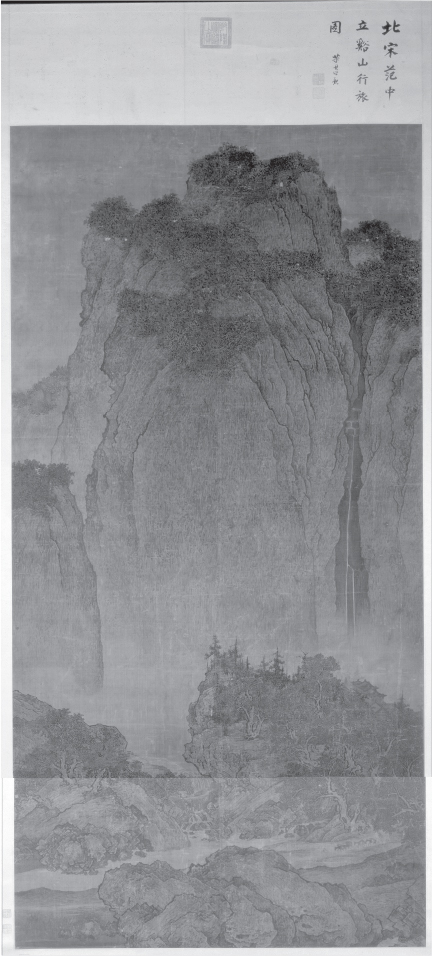

Fan Kuan, Travelers among Mountains and Streams, c. 1000, ink and colors on silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan (Figure 24.5)

Form and Content

■Very complex landscape.

■Different brushstrokes describe different kinds of trees: coniferous, deciduous, etc.

■The long waterfall on the right is balanced by a mountain on the left; the waterfall accents the height of the mountain; embodying the essence of a place rather than likeness.

■Not a pure landscape: donkeys laden with firewood are driven by two men; a small temple appears in the forest; people seen as small and insignificant in a vast natural world.

■Mists, created by ink washes, silhouette the roof of the temple.

Function

■Hanging scroll; meant to be studied and appreciated, not hung permanently.

Context

■The artist isolated himself away from civilization to be with nature and to study it for his landscapes; this reflects a Daoist philosophy.

■The work contains elements of Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.

■This might be the artist’s only surviving work; his signature is hidden in the bushes on the lower right.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 201

Web Source http://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/fan-kuan/travelers-among-mountains-and-streams/

Figure 24.5: Fan Kuan, Travelers among Mountains and Streams, c. 1000, ink and colors on silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Figures Set in Landscape

–Cole, The Oxbow (Figure 20.6)

–Breughel, Hunters in the Snow (Figure 14.6)

–Circle of the Gonzalez family, Screen with the Siege of Belgrade and hunting scene (Figure 18.3b)

Portrait of Sin Sukju, 1417–1475, Imperial Bureau of Painting, 15th century hanging scroll, ink and color on silk (Figure 24.6)

Form

■Hanging scroll.

Function

■May have served as a focus for ancestral rituals after death.

■May have hung in a private setting in a family shrine; hence the emphasis on the rank badge.

■Served as a reminder to his descendants of Sin Sukju’s status in Korean society.

Materials

■Painting on silk was a highly desired and a greatly esteemed product.

Context

■Korean prime minister (1461–1464 and 1471–1475); scholar and soldier, involved in creating the modern Korean alphabet.

■The portrait was made when he was a second-grade civil officer: insignia, or rank badge, designed with clouds and a wild goose.

■Korean portraits emphasize how the subject made a great contribution to the country and how the spirit of loyalty to king and country was valued by Confucian philosophy.

■Repainted over the years, especially in 1475, when Sin Sukju died, as an act of reverence for a departed ancestor.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 205

Web Source http://koreaarthistory.weebly.com/traditional-paintings.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Painting Technique

–Campin, Annunciation Triptych (Figure 14.1)

–Rivera, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park (Figure 22.20)

–Smith, Lying with the Wolf (Figure 29.20)

Figure 24.6: Portrait of Sin Sukju, 1417–1475, Imperial Bureau of Painting, 15th century hanging scroll, ink and color on silk

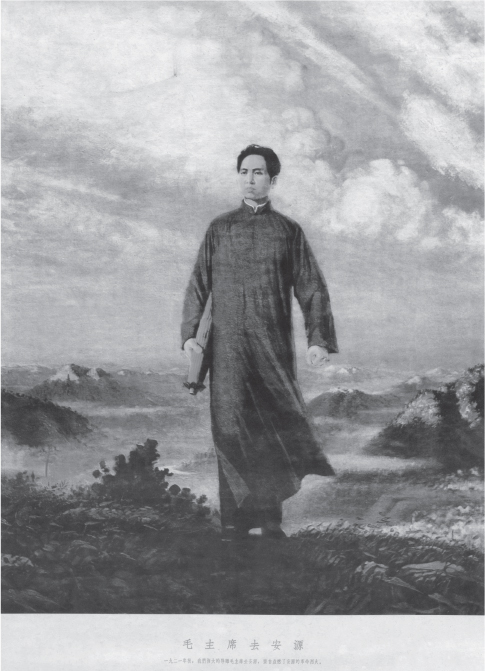

Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan, artist unknown, based on an oil painting by Liu Chunhua, 1969, color lithograph, Private Collection (Figure 24.7)

Form

■Mao rises above a landscape that contains a power line as a symbol of industrialization.

■Iconic representation of the great leader’s career.

■Poster-like; vivid colors, dramatic, and with obvious political message.

Function

■Done as propaganda: Mao appears youthful, heroic, and idealized.

■May be the most reproduced image ever made: 900,000,000 copies were generated.

Context

■Painted during the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976; high art was dismissed as feudal or bourgeois; art was created to be of service to the state.

■Based on an oil painting by Liu Chunhua, which first appeared at the Beijing Museum of the Revolution in 1967.

■This type of art was done anonymously; individual artistic fame was seen as countercultural in a collectivist society.

■A moment in the 1920s; Mao on his way to Anyuan to lead a miners’ strike.

■Mao worked for reforms for miners; supported a local strike for better wages, working conditions, and education.

■For many people, this action formed a permanent bond with the Communist Party.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 212

Figure 24.7: Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan, artist unknown, based on an oil painting by Liu Chunhua, 1969, color lithograph, Private Collection

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Non-Western Works Using Western Ideas

–Bandolier bag (Figure 26.11)

–Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene (Figure 28.7)

–Frontispiece of the Codex Mendoza (Figure 18.1)

CHINESE SCULPTURE

China is a monumental civilization that has produced large-scale sculpture as a sign of grandeur. Enormous scale, without sacrificing artistic integrity, is a typical Chinese characteristic epitomized by the terra cotta army of Shi Huangdi (Figures 24.8a and 24.8b) and the huge seated Buddha at Longmen (Figure 24.9a). The Chinese have created a dazzling number of sculptures cut from the rock in situ, a technique probably imported from India.

At the same time, Chinese sculpture is known for intricately designed miniature objects. Those made of jade are especially prized for their beauty; they are durable and polished to a high shine in a matte green-gray color.

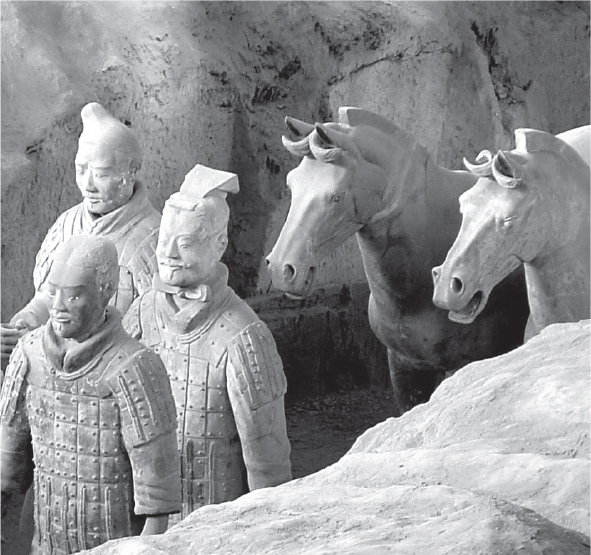

Terra cotta warriors from the mausoleum of the first Qin emperor of China, Qin Dynasty, painted terra cotta, c. 221–209 B.C.E., Lintong, China (Figures 24.8a and 24.8b)

Form

■About 8,000 terra cotta warriors, 100 wooden chariots, 2 bronze chariots, 30,000 weapons.

■Soldiers are 6-feet tall—taller than the average person of the time; some are fierce, some proud, some confident; actually held metal weapons.

■Originally colorfully painted.

■Tomb oriented north–south.

■The tomb has a rectangular double-walled enclosure.

Figure 24.8a: Terra cotta warriors from the mausoleum of the first Qin emperor of China, Qin Dynasty, painted terra cotta, c. 221–209 B.C.E., Lintong, China

Function

■Tomb of Emperor Shi Huangdi, founder of the first unified Chinese empire.

Context

■The work represents a Chinese army marching into the next world.

■Each soldier’s face is unique and expresses the army’s ethnic diversity.

■Daoism is seen in the individualization of each soldier despite their numbers.

■This is an early form of mass production, alluding to the power of the state.

■Discovered in 1974.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 193

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/pg.cfm?cid=31&id_site=441

Figure 24.8b: Terra cotta warriors

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Intentionally Buried Works

–Tomb of Tutankhamun (Figure 3.11)

–Catacomb of Priscilla (Figure 7.1a)

–Tomb of the Triclinium (Figure 5.3)

Longmen Caves, 493–1127, Tang Dynasty, limestone, Luoyang, China (Figures 24.9a, 24.9b, and 24.9c)

Form

■The Buddha is arranged as if on an altar of a temple, deeply set into the rock face.

■Vairocana Buddha is flanked by monk attendants, bodhisattvas, and guardians; perhaps a portrait of Wu Zetian.

■The figures have elongated legs and exaggerated poses.

■Sculptures and reliefs are carved from the existing rock—some colossal, some small.

■Realistic musculature of the heavenly guardians (Figure 24.9b) shows them as able protectors and defenders of the faith.

Figure 24.9a: Longmen Caves with Vairocana Buddha, 493–1127, Tang Dynasty, limestone, Luoyang, China

Patronage

■Inscription states that Empress Wu Zetian was the principal patroness of the site and that she used her private funds to finance the project.

Figure 24.9b: Longmen Caves detail

Context

■More than 2,300 caves and niches are carved along the banks of the Yi River.

■Documents attest that 800,000 people worked on the site; they produced 110,000 Buddhist stone statues, more than 60 stupas, and 2,800 inscriptions on steles.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 195

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1003

Figure 24.9c: Longmen Caves detail

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Grand Outdoor Sculpture

–Great Altar of Zeus and Athena at Pergamon (Figures 4.18a, 4.18b)

–Bamiyan Buddha (Figure 23.2)

–Moai (Figure 28.11)

Gold and jade crown, Three Kingdoms period, Silla Kingdom, 5th–6th century, metalwork, National Museum of Korea, Seoul, South Korea (Figure 24.10)

Function

■Crown is very lightweight and therefore had limited use—maybe for ceremonial occasions or perhaps only for burial.

Context

■Stylized geometric shapes symbolize trees.

■Antler forms influenced by shamanistic practices in Siberia.

■Uncovered from a royal tomb in Gyeongju, Korea; from the Silla Dynasty.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 196

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2013/koreas-golden-kingdom

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Metalwork

–Merovingian looped fibulae (Figure 10.1)

–Golden Stool (Figure 27.4)

–El Anatsui, Old Man’s Cloth (Figure 29.23)

Figure 24.10: Gold and jade crown, Three Kingdoms period, Silla Kingdom, 5th–6th century, metalwork, National Museum of Korea, South Korea

PORCELAIN

Almost every world culture has a tradition of ceramics, few as fine as those from China. Originally most ceramics were made by the coiling method, in which clay was rolled onto a long, flat surface so that it resembles a long cord. The cords were wrapped around themselves creating a sculpture, sometimes of considerable size. To remove the appearance of the coils, the edges were often smoothed out with the artist’s hands or an instrument.

Later the clay was placed on a round tray and made to revolve using a pedal; this began the invention of the potter’s wheel. The process of making pottery on a wheel is called throwing. The potter uses his or her hands to shape the pottery as it revolves.

Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) vases have a distinctive blue and white color. The cobalt used to make the iridescent blue was imported from Iran and greatly prized by the Chinese.

The David Vases, Yuan Dynasty, 1351, white porcelain with cobalt-blue underglaze, British Museum, London (Figure 24.11)

Form and Content

■The blue color was imported from Iran; Chinese expansion into western Asia made the cobalt blue available.

■The vases were modeled after bronzes of the same type.

■The necks and feet of the vases contain leaves and flowers.

■They have elephant-head-shaped handles.

■Central section: Chinese dragons with traditional long bodies and beards; dragons have scales and claws, and are set in a sea of clouds.

Figure 24.11: The David Vases, Yuan Dynasty, 1351, white porcelain with cobalt-blue underglaze, British Museum, London

Function

■Made for the altar of a Daoist temple along with an incense burner, which has not been found; a typical altar set.

■Site heavily damaged during the twentieth century.

Materials

■Made of Jingdezhen porcelain, the same materials found in Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (cf. Figure 29.27).

Context

■One of the most important examples of Chinese blue and white porcelain in existence.

■A dedication is written on the side of the neck of the vessels; believed to be the earliest known blue-and-white porcelain dedication.

■Inscription on one of the vases: “Zhang Wenjin, from Jingtang community, Dejiao village, Shuncheng township, Yushan county, Xinzhou circuit, a disciple of the Holy Gods, is pleased to offer a set comprising one incense-burner and a pair of flower vases to General Hu Jingyi at the Original Palace in Xingyuan, as a prayer for the protection and blessing of the whole family and for the peace of his sons and daughters. Carefully offered on an auspicious day in the Fourth Month, Eleventh year of the Zhizheng reign.”

■Named after Sir Percival David, a collector of Chinese art.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 204

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Porcelain and Ceramic

–Martínez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel (Figure 26.14)

–Niobides Krater (Figures 4.19a, 4.19b)

–Terra cotta warriors (Figures 24.8a, 24.8b)

VOCABULARY

Bi: a round ceremonial disk found in ancient Chinese tombs; characterized by having a circular hole in the center, which may have symbolized heaven

Bodhisattva: a deity who refrains from entering nirvana to help others (Figure 24.9c)

Coiling: a method of creating pottery in which a rope-like strand of clay is wrapped and layered into a shape before being fired in a kiln

Colophon: a commentary on the end panel of a Chinese handscroll; an inscription at the end of a manuscript containing relevant information on its publication (Figure 24.3a)

Confucianism: a philosophical belief begun by Confucius that stresses education, devotion to family, mutual respect, and traditional culture

Daoism: a philosophical belief begun by Laozi that stresses individual expression and a striving to find balance in one’s life

Hanja: Chinese characters used in Korean script with a Korean pronunciation

Literati: a sophisticated and scholarly group of Chinese artists who painted for themselves rather than for fame and mass acceptance. Their work is highly individualized

Pagoda: a tower built of many stories. Each succeeding story is identical in style to the one beneath it, only smaller. Pagodas typically have dramatically projecting eaves that curl up at the ends

Porcelain: a ceramic made from clay that when fired in a kiln produces a product that is hard, white, brittle, and shiny

Potter’s wheel: a device that usually has a pedal used to make a flat circular table spin, so that a potter can create pottery

Throwing: molding clay forms on a potter’s wheel

Vairocana: the universal Buddha, a source of enlightenment; also known as the Supreme Buddha who represents “emptiness,” that is, freedom from earthly matters to help achieve salvation (Figure 24.9c)

Yin and yang: complementary polarities. The yin is a feminine symbol that has dark, soft, moist, and weak characteristics. The yang is the male symbol that has bright, hard, dry, and strong characteristics (Figure 24.3c)

SUMMARY

The great Chinese philosophies of Daoism and Confucianism dominate the fine arts, as well as all intellectual thought in China. They express the relationship of buildings to one another in courtyard-style residences from the most humble to the Forbidden City. They also articulate a relationship of the forms in Chinese painting.

Chinese artists apprenticed under a master and worked under a system of patronage controlled by religion or government. A powerful minority, the literati, deliberately chose to walk away from traditional artistic venues and cultivate a more individualized type of art.

Chinese art has a penchant for the monumental and the grand, epitomized by the Great Wall, the Colossal Buddhas, and the Tomb of Shi Huangdi. Considerable attention, however, is paid to smaller items such as delicate porcelains, finely cut jade figures, and laquered wooden objects.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.The tomb of the Terra cotta warriors from the first Qin emperor of China has more than 8,000 soldiers who are

(A)alike to show their uniformity in protecting the emperor

(B)unpainted to contrast with the colorful image of the emperor more forcefully

(C)subtly different to show their ethnic diversity of China

(D)from every social class, gender, and age in China

Questions 2–4 refer to this image.

2.This Korean crown was found

(A)in a royal sanctuary placed with other religious objects

(B)on the head of a large sculpture of Buddha

(C)in a royal tomb buried in a mound

(D)in Japan, given as a diplomatic gift to the Japanese emperor

3.It is assumed that the crown was probably not meant to be worn because

(A)the gold is too precious and would have been easily stolen

(B)gold is a soft metal that could be easily bent if worn

(C)the gold applied here is extremely thin and fragile

(D)the whole crown was too heavy to be worn comfortably

4.The uprights probably symbolized

(A)a distinctive royal lineage of a “family tree” that came from the gods to the wearer

(B)a stylized tree with antler forms that denoted spiritual power

(C)everlasting peace achievable through the gods and the divinely appointed emperor

(D)the riches of an earthly kingdom reflecting the glory of an eternal world

5.Which of the following Chinese art forms inspired contemporary artwork?

(A)Chinese music as seen in Horn Players

(B)Chinese porcelains as seen in Pink Panther

(C)Chinese photography as seen in Rebellious Silence

(D)Chinese writing as seen in A Book from the Sky

Long Essay

Practice Question 2: Visual and Contextual Analysis

Suggested Time: 25 minutes

As a faith, Buddhism has often had a strong impact on the art of Asia.

Select and completely identify a work of Buddhist art from the list below, or any other relevant work from Asia.

Explain how artists or architects have constructed Buddhist monuments to reflect the imagery and practice of the Buddhist faith as seen in the work you have selected.

In your answer, make sure to:

■Accurately identify the work you have chosen with at least two identifiers beyond those given.

■Respond to the question with an art historically defensible thesis statement.

■Support your claim with at least two examples of visual and/or contextual evidence.

■Explain how the evidence that you have supplied supports your thesis.

■Use your evidence to corroborate or modify your thesis.

Great Stupa at Sanchi

Longmen Caves

Todai-ji

ANSWER KEY

1.C

2.C

3.C

4.B

5.D

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(C) Each of the figures is subtly different to depict various ethnic features in different regions of China. There are no women, or old or young people.

2.(C) The crown was found in a tumulus, or burial mound.

3.(C) The gold is extremely thin and very fragile; it was meant only for limited occasions or mostly likely burial.

4.(B) The uprights symbolize a stylized tree reaching up to the sky. They have connections with spiritual forces.

5.(D) Xu Bing’s A Book from the Sky contains references to traditional Chinese art, bookmaking, and calligraphy, although much of the calligraphy is made up.

Long Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Accurately identify the work you have chosen with at least two identifiers beyond those given. |

1 |

■For the Great Stupa at Sanchi: Madhya Pradesh, India, late Sunga Dynasty, c. 300 B.C.E.–100 C.E.; stone masonry, sandstone on dome. ■For Longmen Caves: Laoyang, China, Tang Dynasty, 493–1127 C.E., limestone. ■For Todai-ji: Nara, Japan, various artists including sculptors Unkei and Keikei as well as the Kei School, 743, rebuilt c. 1700, bronze and wood (sculpture) wood with ceramic-tile roofing (architecture). |

Respond to the question with an art historically defensible thesis statement. |

1 |

The thesis statement must be an art historically sound claim that responds to the question and does not merely restate it. The thesis statement should come at the beginning of the argument and be at least one, preferably two sentences. For example: The Longmen Caves represent an extensive Buddhist monument that is composed of 2,300 caves and niches dedicated to the worship of Buddha. The main focus is a huge sculpture of Buddha that is set on an altar-like pedestal. |

Support your claim with at least two examples of visual and/or contextual evidence. |

2 |

Two visual or contextual examples are needed to supply the necessary evidence. Part of the evidence could involve a discussion of how the artist has rendered stories about Buddha, or how the stupa functions in Buddhist worship, or how Buddhist shrines are constructed in Japan. |

Explain how the evidence that you have supplied supports your thesis. |

1 |

Good responses link the evidence you have provided with the main thesis statement. With these examples, you could discuss how patronage has played a role in the artists’ rendering of the Buddha image or a Buddhist shrine. |

Use your evidence to corroborate or modify your thesis. |

1 |

This point is earned when a student demonstrates a depth of understanding, in this case of Buddhist monuments. The student must demonstrate multiple insights on a given subject. For example, you could discuss how Asian artists have manifested the image of Buddha in different ways and yet have remained true to the overall Buddhist tradition. |