Content Area: The Pacific, 700–1980 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: FROM ANCIENT TIMES TO THE PRESENT

Except for the Easter Island sculptures, which date from the tenth century, most surviving Pacific Art dates from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Buk (mask))

Essential Knowledge:

■ Pacific art is seen as a whole: the work of art exists in the context of events, media, and ceremonies. There is a wide variety of materials used in Pacific art.

■ Among the materials used in Pacific art are bone, seashell, fiber, wood, stone, and coral, as well as tortoise shell.

■ Materials are likely to create a response in the audience; i.e., precious objects denote wealth.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting has affected the making of a work of art. (For example: Maoi from Rapa Nui)

Essential Knowledge:

■ The Pacific has 1,500 inhabited islands, each with a distinct ecology.

■ Australia was populated 30,000 years ago. The Lapita people migrated east about 4,000 years ago.

■Pacific peoples are seafaring.

■The sea is a major theme in Pacific art.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Presentation of Fijian mats and tapa cloths to Queen Elizabeth II)

Essential Knowledge:

■ Pacific art has been influenced by ecology, colonialism, social structure, missionary activity, and commerce.

■ Europeans encountered the Pacific in the sixteenth century. Later, they divided the region into three distinct zones: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Nan Madol)

Essential Knowledge:

■ Pacific art is related to forces in the spiritual world. One’s vital force, or mana, was often wrapped or shielded to be protected. Sometimes mana could represent a whole community. The act of protecting the mana through rituals or wrapping is called tapu.

■ Pacific art is often performed using dance, singing, costuming, scent, and cosmetics.

■Objects often illustrate familial and societal history. Others are created to be performed and later destroyed.

■ Sacred ceremonial spaces are common in the Pacific. Masks are key elements in Pacific performances.

■Rituals and performances often involve exchanging prearranged items that have symbolic value.

■A symmetry of relationships is often sought. Opposing forces, such as gender, are placed within a balancing situation in many rituals.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene)

Essential Knowledge:

■ Pacific art is an expression of a collection of beliefs and social relationships.

■Creating or destroying a work of art often carries great significance, sometimes more significant than the object itself. The act of performance contains the work’s meaning. The objects in that performance contain no meaning unless brought to life by rituals.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Certain areas of the Pacific are some of the oldest inhabited places on earth, and yet, paradoxically, some areas are among the newest. Aborigines reached Australia around 50,000 years ago, but the remote islands of the Pacific, like Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand were occupied only in the last thousand years or so.

Around 1300 B.C.E. seafarers reached across the vast oceanic expanses to chart their way toward Fiji in the central South Pacific. Technological development of sailing craft meant greater territories could be mapped and charted for possible occupation. The particularly effective twin-hulled sailing canoe was used to traverse hundreds of nautical miles; Tonga was reached in 420 B.C.E., and then Samoa in 200 B.C.E.

The final push to populate the Pacific came with the discovery of New Zealand. This happened perhaps as early as the tenth century, but certainly by the thirteenth century by the ancestors of the Maori.

European involvement in the Pacific began with the circumnavigation of the globe by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and his crew. Explorers of the eighteenth century were followed by occupiers from the nineteenth century, who implanted European customs, values, religions, and technologies onto the indigenous population. Many areas of the Pacific, however, achieved independence in the twentieth century.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Men and women had clearly defined roles in Pacific society, including which sex could create works of art in which media. Men carved in wood, woman sewed and made pottery.

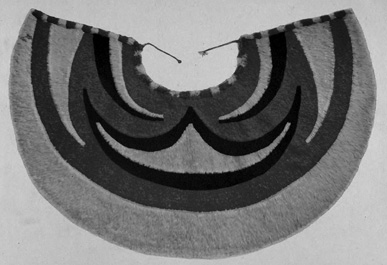

One of the most characteristic works still done by Pacific women is the weaving of barkcloth, or tapa (Figure 28.6). The inner bark of the mulberry tree is harvested and small strips are made malleable by repeated soakings. Each strip is placed in a pattern and then beaten in order to fuse them together. Designs were added by stenciling or painting directly onto the surface. The result is a cloth of refined geometric organization and intricate patterning.

MICRONESIA

Nan Madol, Saudeleur Dynasty, c. 700–1600, basalt boulders and prismatic columns, Pohnpei, Micronesia (Figures 28.1a and 28.1b)

Form

■ 92 small artificial islands connected by canals, about 170 acres in total.

■ Built out into the water on a lagoon—similar to Venice, Italy.

■ Seawalls 15 feet high and 35 feet thick acted as breakwaters.

■Canals were flushed clean with the tides.

■Islands were arranged southwest to northeast to take advantage of the trade winds.

■ Walls were made of prismatic basalt; roofs were thatched.

Function

■ Ancient city that acted as the capital of the Saudeleur Dynasty of Micronesia.

Context

■City built to separate the upper classes from the lower classes.

■ King arranged for the upper classes to live close to him, to keep an eye on them.

■Curved outer walls point upward at edges, giving the complex a symbolic boat-like appearance.

Figure 28.1a: Nan Madol, Saudeleur Dynasty, c. 700–1600, basalt boulders and prismatic columns, Pohnpei, Micronesia

Figure 28.1b: Nan Madol, Saudeleur Dynasty, c. 700–1600, basalt boulders and prismatic columns, Pohnpei, Micronesia

Content Area Pacific, Image 213

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1503

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Water and Architecture

–Ryoan-ji (Figures 25.2a, 25.2b, 25.2c)

–Gehry, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (Figures 29.1a, 29.1b)

–Wright, Fallingwater (Figures 22.16a, 22.16b, 22.16c)

Female deity, c. 18th to 19th century, wood, Nukuoro, Micronesia (Figure 28.2)

Figure 28.2: Female deity, c. 18th–19th century, wood, Nukuoro, Micronesia

Form

■Simple geometric form.

■Erect pose, long arms, broad chest.

■Chin drawing to a point; no facial features.

■Horizontal lines were used to indicate kneecaps, navel, and waistline.

Function

■ Female deity.

Context

■Many were kept in religious buildings belonging to the community.

■They represent individual deities.

■Sometimes they were dressed in garments; may have been decorated with flowers.

■Taken by missionaries who did not record anything about the sculptures.

Content Area Pacific, Image 217

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Wood Sculpture

–Olowe of Ise, veranda post (Figure 27.14)

–Nio guardian figure (Figure 25.1c, 25.1d)

–Röttgen Pietà (Figure 12.7)

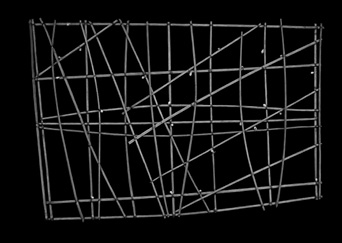

Navigation chart, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, 19th to early 20th century, wood and fiber, British Museum, London (Figure 28.3)

Figure 28.3: Navigation chart, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, 19th to early 20th century, wood and fiber, British Museum, London

Form

■Chart is made of wood, therefore waterproof and buoyant.

■Small shells indicate the position of the islands on the chart.

■Horizontal and vertical sticks support the chart.

■Diagonal lines indicate wind and water currents.

■Charts indicate patterns of ocean swells and currents.

Function

■Charts meant to be memorized prior to a voyage; not necessarily used during a voyage.

■Charts enabled navigators to guide boats through the many islands to get to a destination.

■Charts were individualized to their makers; others cannot read the chart.

Context

■Marshall Islands are low lying and hard to see from a distance or from sea level.

■Charts are called wapepe in the Marshall Islands.

Content Area Pacific, Image 221

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1978.412.826/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Utility

–Ambum Stone (Figure 1.4)

–The Ardabil Carpet (Figure 9.7a)

–Pyxis of al-Mughira (Figure 9.4)

Figure 28.4: ‘Ahu ‘ula (feather cape), late 18th century, feathers and fiber, British Museum, London

HAWAII

‘Ahu ‘ula (feather cape), late 18th century, feathers and fiber, British Museum, London (Figure 28.4)

Materials

■ The cape is made of thousands of bird feathers.

■Feathers numbered 500,000; some birds had only seven usable feathers.

■The feathers were tied to a coconut fiber base.

Function

■Only high-ranking chiefs or warriors of great ability were entitled to wear these garments; worn by men.

Context

■ Red was considered a royal color in Polynesia; yellow was prized because of its rarity.

■The cape was created by artists who chanted the wearer’s ancestors to imbue their power onto it.

■ It protected the wearer from harm.

■The concept of “mana:” a supernatural force believed to dwell in a person or sacred object.

■Many capes have survived, but no two capes are alike.

Content Area Pacific, Image 215

Web Source http://honolulumuseum.org/art/5780-feather-cape-ahu-ulaa_z

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Regalia

–Ruler’s feathered headdress (Figure 26.6)

– Gold and jade crown (Figure 24.10)

–Ndop Contextual Photograph (Figure 27.5b)

Figure 28.5a: Staff god, Rarotonga, Cook Islands, central Polynesia, late 18th to early 19th century, wood, tapa, fiber, and feathers, British Museum, London

Figure 28.5b: Staff god, Rarotonga

COOK ISLANDS

Staff god, Rarotonga, Cook Islands, central Polynesia, late 18th to early 19th century, wood, tapa, fiber, and feathers, British Museum, London (Figures 28.5a and 28.5b)

Form and Content

■Large, column-like, wooden core mounted upright in village common spaces; the wooden core is wrapped with tapa cloth (i.e., Hiapo, Figure 28.6).

■The wooden sculpture placed on top features a large carved head with several smaller figures carved below it (Figure 28.5a).

■ The shaft is in the form of an elongated body (Figure 28.5b).

■The lower end had a carved phallus. Some missionaries removed and destroyed the phalluses, considering them obscene.

■The soul of the god is represented by polished pearl shells and red feathers, which are placed inside the bark cloth next to the interior shaft.

Context

■Most staff gods were destroyed; only the top ends were retained as trophies.

■This is the only surviving wrapped example of a staff god.

■In the contextual image from a book by an English missionary (not shown), the staff gods have been thrown down in the village square in front of a European-style church; it represents the fall of one faith and the adoption of another.

■The contextual image is the only visual evidence that indicates how these staff gods were used.

■ Reverend John Williams observed that the barkcloth contained red feathers and pieces of pearl shell, known as the manava or the spirit of the god. He also recorded seeing the islanders carrying the image upright on a litter.

Content Area Pacific, Image 216

Web Source https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/god-stick-with-barkcloth/OwEzoiWYHZRkdA

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Gods and Spiritual Presences

–Last Judgment, Sainte-Foy, Conques (Figure 11.6a)

–Great Buddha, Todai-ji, (Figure 25.1b)

–Shiva as Lord of Dance (Figure 23.6)

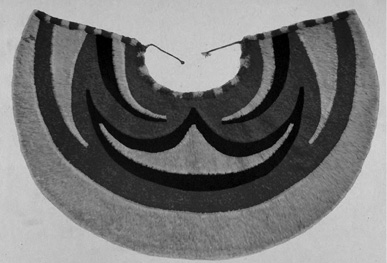

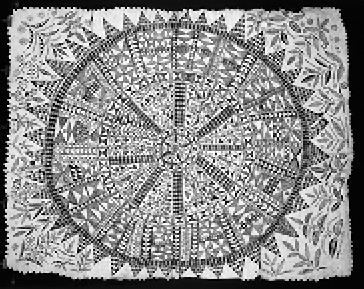

Figure 28.6: Hiapo (tapa) from Niue, c. 1850–1900, tapa or bark cloth, freehand painting, Auckland War Memorial Museum, New Zealand

POLYNESIA

Hiapo (tapa) from Niue, c. 1850–1900, tapa or bark cloth, freehand painting, Auckland War Memorial Museum, New Zealand (Figure 28.6)

Technique

■Tapa is cloth made from tree bark; the pieces are beaten and pasted together.

■Using stencils, the artists dye the exposed parts of the tapa with paint.

■After the tapa is dry, designs are sometimes repainted to enhance the effect.

Function

■Traditionally worn as clothing before the importation of cotton.

Context

■Hiapo is the word used in Niue for tapa (bark cloth).

■Tapa takes on a special meaning: commemorating an event, honoring a chief, noting a series of ancestors.

■Tapa is generally made by women.

■Each set of designs is meant to be interpreted symbolically; many of the images have a rich history.

Content Area Pacific, Image 219

Web Source http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/collection/object/am_humanhistory-object-81487

■ Cross-Cultural Connections: Art Forms Traditionally Associated with Women

–Martínez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel (Figure 26.14)

–All-T’oqapu tunic (Figure 26.10)

–Ringgold, Dancing at the Louvre (Figure 29.11)

NEW ZEALAND

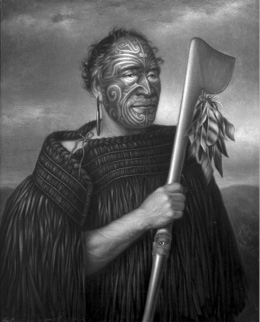

Tamati Waka Nene, Gottfried Lindauer, 1890, oil on canvas, Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand (Figure 28.7)

Figure 28.7: Tamati Waka Nene, Gottfried Lindauer, 1890, oil on canvas, Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

Subject

■ Subject is Tamati Waka Nene (c. 1780–1871), Maori chief and convert to the Wesleyan faith.

■ Painting is posthumous, based on a photograph by John Crombie.

Content

■Emphasis is placed on symbols of rank: elaborate tattooing with Maori designs, staff with an eye in the center, feathers dangling from the staff.

■Ceremonial weapon has a finely wrought blade with dangling feathers and abalone shell as a focal point or eye.

■ Status is revealed in oversize greenstone earring, which contains his power, or “mana,” and kiwi feather cloak.

Context

■ The painter was born in Bohemia and was famous for portraits of Maori chieftains upon his arrival in New Zealand in 1873–1874 until his death in 1926.

■ He was a journeyman painter and tradesman who worked on commission.

■This is a European-style painting in its use of oil paint, canvas backing, coloring, modeling, shading, and atmospheric perspective.

■ Conflicting interpretations of works such as these:

–Maori may see the portraits as an embodiment of the spirit of a person, and as a link between past and present.

–Westerners may see the paintings as a commercial adventure with a monetary value.

–Some may see the portrait as a record of a vanishing culture.

–Others may interpret the work as anthropology highlighting aspects of Maori costuming and physiognomy, and what they could mean.

–Still others may see the portraits as expressions of colonial dominance.

Content Area Pacific, Image 220

Web Source http://www.aucklandartgallery.com/explore-art-and-ideas/artist/2164/gottfried-lindauer

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Rulers

–Houdon, George Washington (Figure 19.7)

–Wall plaque, from Oba’s palace (Figure 27.3)

–Augustus of Prima Porta (Figure 6.15)

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

Malagan mask, New Ireland Province, Papua New Guinea, c. 20th century, wood, pigment, fiber, and shell, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas (Figure 28.8)

Figure 28.8: Malagan mask, New Ireland Province, Papua New Guinea, c. 20th century, wood, pigment, fiber, and shell, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas

Form

■ Masks are extremely intricate in their carving.

■ They are painted black, yellow, and red: important colors denoting violence, war, and magic.

■Artists are specialists in using negative space.

Function

■ Sculptures of the deceased are commissioned; they represent the individual’s soul, or life force, not a physical presence.

■The mask indicates the relationship of a particular deceased person to a clan and to living members of the family.

■ The large haircomb reflects a hairstyle of the time; masks are not physical portraits, only portraits of the soul.

Context

■ Malagan ceremonies send the souls of the deceased on their way to the otherworld.

■ Sometimes ceremonies begin months after death and last an extended period of time.

■During the time after death the sponsors must organize the ceremonies and the feasts. They must also hire the sculptors who will carve the structures for the event.

■ An expensive undertaking: families often combine their wealth and honor several individuals.

■The commissioned malagan sculptures are exhibited in temporary display houses. Each sculpture honors a specific individual and illustrates his or her relationships with ancestors, clan totems, and/or living family members.

■ During the course of the ceremony it is believed that the souls of the deceased enter the sculptures.

■ The ceremonies free the living from the obligation of serving the dead.

■Structures are erected to suit a purpose; after the ceremony, the structures are considered useless and usually destroyed or allowed to rot—they have fulfilled their function.

Content Area Pacific, Image 222

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nwir/hd_nwir.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Faces

–Mblo (Figure 27.7)

–Head of a Roman patrician (Figure 6.14)

–Reliquary of Sainte-Foy (Figure 11.6c)

Buk (mask), Torres Strait, mid- to late 19th century, turtle shell, wood, fiber, feathers, and shell, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Figure 28.9)

Figure 28.9: Buk (mask), Torres Strait, mid- to late 19th century, turtle shell, wood, fiber, feathers, and shell, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

■Some masks combine human and animal forms; this mask shows a bird placed on top.

■ Turtle shell masks are unique to this region.

Function

■The mask, like a helmet, is worn over the head.

■Part of a larger grass costume used in ceremonies about death, fertility, or male initiation, perhaps even to ensure a good harvest.

■Ceremonies involved fire, drum beats, and chanting; recreating mythical ancestral beings and their impact on these people in everyday activities.

Context

■ Torres Strait is the water passageway between Australia and New Guinea.

■ Human face may represent a cultural hero or ancestor.

Content Area Pacific, Image 218

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1978.412.1510/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Masks

–Aka elephant mask (Figure 27.12)

–Olmec mask (Figure 26.5d)

–Transformation mask (Figures 26.12a, 26.12b)

FIJI

Presentation of Fijian mats and tapa cloths to Queen Elizabeth II during the 1953–1954 royal tour, 1953, multimedia performance, photographic documentation, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand (Figure 28.10)

Figure 28.10: Presentation of Fijian mats and tapa cloths to Queen Elizabeth II during the 1953–1954 royal tour, 1953, multimedia performance, photographic documentation, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Materials

■ Costume, cosmetics including scent.

■Chant; movement; pandanus fiber/hibiscus fiber mats.

Technique

■Men oversee the growth of the mulberry trees that produce the tapa; women turn the bark into cloth.

–Bark is removed from the tree, soaked in water, and treated to make it pliable.

–Clubs are used to beat the strips into a long rectangular block to form pieces of cloth.

– The edges of these smaller pieces are then glued or felted together to produce large sheets.

–The tapa is decorated according to a local tradition; sometimes stenciled, sometimes printed or dyed.

Function

■Enormous tapa clothes were made and presented to Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 in commemoration of her visit to Fiji on the occasion of her coronation as queen of England.

Context

■ The presentation to the queen is an example of performance art.

■ Cf. Lapita geometric motifs (Figure 1.6).

Content Area Pacific, Image 223

Web Source https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x_PeKOvr0ng

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Performance

– Viola, The Crossing (Figures 29.18a, 29.18b)

–Lukasa (memory board) (Figure 27.11)

EASTER ISLAND (RAPA NUI)

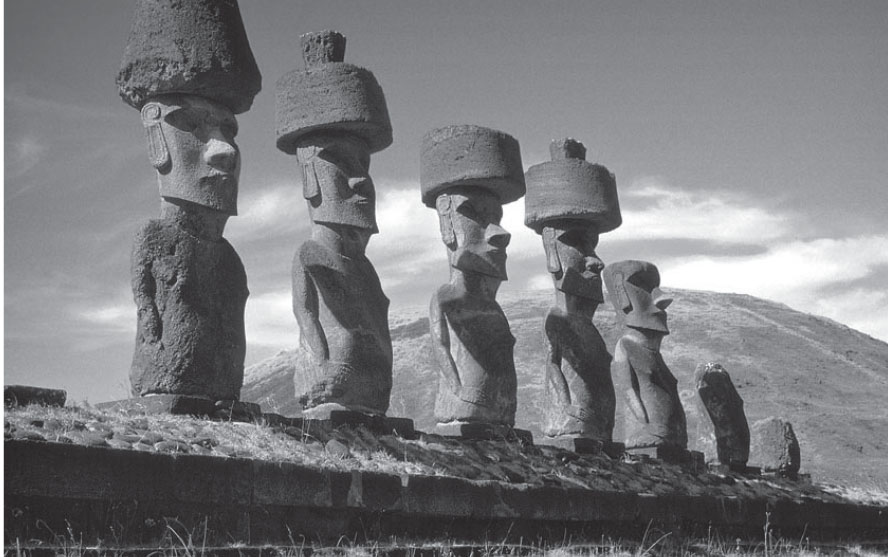

Moai on platform (ahu), c. 1100–1600, volcanic tuff figures on basalt base, Easter Island (Rapa Nui) (Figure 28.11)

Figure 28.11: Moai on platform (ahu), c. 1100–1600, volcanic tuff figures on basalt base, Easter Island (Rapa Nui)

Form

■Prominent foreheads; large broad noses; thin pouting lips; ears that reach to the top of their heads.

■ Short, thin arms fall straight down; hands on hips; hands across lower abdomen below navel.

■ Breasts and navels are delineated.

■ Backs are tattooed.

■ Topknots were added to some statues.

■White coral was placed in the eyes to “open” them.

Function

■Images represent personalities deified after death or commemorated as the first settler-kings.

Context

■There are about 900 statues in all, 50 tons apiece, mostly male; almost all facing inland.

■ They were erected on large platforms, called ahu, of stone mixed with ashes from cremations; the platforms are as sacred as the statues that are on them.

■ After being carved, figures were said to have been “walked” into place from where they were quarried.

■Beneath an ahu is a cemetery where village elders were buried.

■The depletion of resources may have caused an ecological crisis which led to a decline in society and the destruction of the monuments.

■ Monuments were toppled face down because it was believed that the eyes had spiritual power.

Content Area Pacific, Image 214

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/715

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Large-Scale Stone Sculpture

–Buddha from Bamiyan (Figure 23.2a, 23.2b)

– Lamassu (Figure 2.5)

– Longmen Caves Vairocana Buddha (Figure 24.9a, 24.9b, 24.9c)

VOCABULARY

‘Ahu ‘ula: Hawaiian feather cloaks (Figure 28.4)

Malagan: a large, traditional ceremony from Papua New Guinea, as well as the masks and costumes used in that ceremony (Figure 28.8)

Mana: a supernatural force believed to dwell in a person, or a sacred object (Figure 28.4)

Moai: large stone sculptures found on Easter Island (Figure 28.11)

Tapa: a cloth made from bark that is soaked and beaten into a fabric (Figure 28.6)

Wapepe: navigation charts from the Marshall Islands (Figure 28.3)

SUMMARY

The great expanses of the Pacific were peopled gradually over thousands of years. Indeed, the vast stretch of ocean is matched by the immense variety of artwork produced by disparate people speaking a myriad of languages.

A few generalities about Oceanic Art can be stated with foundation. Many items are portable, usually created for use in a ceremony, and made of wood or bark. When large wooden objects are introduced, they are carved with great precision using the whole of a wooden log. Intricately woven fabrics made of natural materials are a particular Pacific specialty. In all cases, intricate line definition is a hallmark of Oceanic artistic output.

None of these characteristics apply to the art of Easter Island, a unique place in which giant stone sculptures dominate a windswept landscape. These large torsos and heads find their closest artistic affinities with the cultures of ancient America, but the connection between the two cultures is still largely unproven.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

Questions 1 and 2 refer to the illustration below.

1.This type of garment is used in which of the following contexts?

(A)It established a royal lineage by discrediting rivals to the throne.

(B)It linked the wearer to the gods.

(C)It made a connection between the human world and the world of lizards and snakes.

(D)It cast a spell on enemies.

2.This garment belonged to

(A)Hawaiian royalty

(B)Motecuhzoma II

(C)King Mishe miShyaang maMbul

(D)Coyolxauhqui

3.The Processional Welcoming Queen Elizabeth II is analogous in content to

(A)Plaque of the Ergastines

(B)Forum of Trajan

(C)Bayeux Tapestry

(D)Grave stele of Hegeso

4.The weaving technique used to make tapa requires

(A)a heating process whereby the fabric is covered with wax and the threads are melted in place

(B)the use of silk threads to be woven onto a background of sheep’s wool

(C)beating soaked strips of tree bark into a flat surface to be later woven into a cloth-like fabric

(D)stitching thread into a pre-made backing to form a design

5.Prehistoric works from the Pacific, such as the Ambum Stone, illustrate the ongoing tradition of using animal motifs that appear in such works as

(A)the Moai from Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

(B)Navigation charts

(C)Buk masks

(D)the female deity from Nukuoro

Long Essay

Practice Question 1: Comparison

Suggested Time: 35 minutes

NOTE: Since the Pacific unit is such a small proportion of the testing material, the College Board has indicated that it is not likely that a long essay question will appear on this subject. However, an essay question is presented here so that students can practice a comparison essay.

The work shown, the ‘Ahu ‘ula (feather cape), is part of a ceremonial garb.

Select and completely identify another work of art that is a ceremonial garb. You may choose from the list below or any other relevant work.

Analyze how each work was meant to be used in a ceremony.

For each work, describe the relationship between its artistic decoration and its function in a ceremony.

For each work, explain the significance or symbolism of the work to contemporaries.

How does each work differ in function?

Ruler’s feather headdress

Aka (elephant mask)

Funeral banner of Lady Dai

ANSWER KEY

1.B

2.A

3.A

4.C

5.C

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(B) The cloak was created by artists who chanted to the wearer’s ancestors to imbue their power on it. Wearers chanted to create a link between the wearer and the world of spirits.

2.(A) The garment is associated with Hawaiian royalty.

3.(A) The Processional Welcoming Queen Elizabeth II is akin to the Plaque of the Ergastines because in both cases offerings are being made in a ceremonial procession.

4.(C) Tapa is made by beating soaked strips of tree bark into a flat surface to be later woven into a cloth-like fabric.

5.(C) Buk masks contain many animal motifs. The one on the curriculum guide has a turtle shell topped by a bird.

Long Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

For the ‘Ahu ‘ula, answers could include: |

Select and completely identify another work of art that is a ceremonial garb. |

— |

— |

|

Analyze how each work was meant to be used in a ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

■ Only high-ranking chiefs or warriors of great ability were entitled to wear these garments. ■Cape created by artists who chanted the wearer’s ancestors to imbue their power on it. ■ The cape protected the wearer from harm. |

|

For each work, describe the relationship between its artistic decoration and its function in a ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

■ The cape was made of as many as 500,000 bird feathers; it was worn only by men. ■Some birds had only seven usable feathers. ■Rarity of the feathers made the work especially valuable. ■ The feathers were tied to a base of coconut fiber. |

|

For each work, explain the significance or symbolism of the work to contemporaries. |

1 point for each work |

■ In Polynesia, red was considered a royal color; yellow was prized because of its rarity. ■ Polynesian kings wore the cape as a symbol of their rank, prestige, power, and majesty. |

How does each work differ in function? |

1 point shared with the two works |

This depends on the works selected. The Polynesian cape was worn as a symbol and covered the body; the Aztec feather headdress was part of an overall costume; the Lady Dai funeral banner was a burial cloth; the aka elephant mask was part of an elaborate ceremony. |

Task |

Point Value |

For the Ruler’s feather headdress, answers could include: |

Select and completely identify another work of art that is a ceremonial garb. |

1 |

1428–1520, feathers (quetzal and blue cotinga) and gold, Aztec. (Since the title is given in the directions, you may not use it in your identification. Two other identifiers are required.) |

Analyze how each work was meant to be used in a ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

■ It is a ceremonial headdress of a ruler. ■ It’s the only known Aztec feather headdress in the world. |

For each work, describe the relationship between its artistic decoration and its function in a ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

■The long green feathers (as many as 400) are the tails of sacred quetzal birds; male birds produce only two such feathers each. ■Feathers indicate trading across the Aztec Empire. ■Only the wealthy and powerful could trade across an empire for rare bird feathers, proof of the greatness of the king. |

Task |

Point Value |

For the Aka elephant mask, answers could include: |

For each work, explain the significance or symbolism of the work to contemporaries. |

1 point for each work |

■Headdress was possibly part of a collection of artifacts given by Motechuzoma II (Montezuma) to Cortez for the Holy Roman emperor Charles V; if true, it was considered a gift great enough for an emperor. ■The extravagant decorative feathers of the birds of paradise indicate a royal admiration for the exotic and the decorative. |

Task |

Point Value |

For the Aka elephant mask, answers could include: |

Select and completely identify another work of art that is a ceremonial garb. |

1 |

c. 19th–20th century; wood, woven raffia, cloth, and beads; Bamileke. (Since the title is given in the directions, you may not use it in your identification. Two other identifiers are required.) |

Analyze how each work was meant to be used in a ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

■Performance art: maskers dance barefoot to a drum and gong, waving spears and horsetails. ■The elite Kuosi masking society owns the masks, which are worn on important ceremonial occasions. |

For each work, describe the relationship between its artistic decoration and its function in a ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

■The masks have the features of an elephant: a long trunk and large ears (which symbolize strength and power). ■The mask fits over the head, and two folds hang down in front (symbolizing the trunk) and behind the body. ■The beadwork is a symbol of power. ■Eyes, nose, and mouth indicate a human face on the elephant mask. |

For each work, explain the significance or symbolism of the work to contemporaries. |

1 point for each work |

■Only important people in society can own and wear an elephant mask. ■ The power of the elephant (the most massive of land animals) seen in this work symbolizes the power of the wearer. ■The lavish display of colored beads and cowrie shells indicated the wealth of the members of the Kuosi society; the mask’s colors and patterns expressed the society’s cosmic and political functions. |

Task |

Point Value |

For the Funeral banner of Lady Dai, answers could include: |

Select and completely identify another work of art that is a ceremonial garb. |

1 |

c. 180 B.C.E., painted silk, Chinese. (Since the title is given in the directions, you may not use it in your identification. Two other identifiers are required.) |

Analyze how each work was meant to be used in a ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

■T-shaped silk banner covering the inner coffin of the intact body in a tomb. ■Probably carried in a procession to the tomb and then placed over the body to speed its journey to the afterlife. |

For each work, describe the relationship between its artistic decoration and its function in a ceremony. |

1 point for each work |

■Painted in three distinct regions: –Top: Heaven, with the crescent moon at the left and the legend of the ten suns on the right. • In the center, two seated officers guard the entrance to the heavenly world. –Middle: Earth, with Lady Dai in the center on a white platform about to make her journey to heaven with a walking stick that was found in her tomb. •Mourners and assistants appear by her side. •Dragons’ bodies are symbolically circled through a bi in a yin and yang exchange. –Bottom: the underworld, where symbolic low creatures frame the underworld scene: fish, turtles, dragon tails; tomb guardians protect the body. |

For each work, explain the significance or symbolism of the work to contemporaries. |

1 point for each work |

■Lady Dai died in 168 b.c.e. in Hunan province, during the Han Dynasty. ■ A great woman was honored with fine objects buried in the tomb and hence taken to the afterlife. ■ Tomb, with more than 100 objects, was found in 1972. ■ Yin symbols at left; yang symbols at right; the center mixes the two philosophies. |