Content Area: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: 1050–1150, SOME OBJECTS DATE AS EARLY AS 1000 AND AS LATE AS 1200

To nineteenth-century art historians, Romanesque architecture looked like a derivative of ancient Roman art, and they titled the period “Romanesque,” or “in the Roman manner.” Although there are some superficial resemblances in the roundness of architectural forms, the Romanesque period is very different from its namesake.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Church of Sainte-Foy)

Essential Knowledge:

■Romanesque art is a part of the medieval artistic tradition.

■In the Romanesque period, royal courts emphasized the study of theology, music, and writing.

■Romanesque art avoids naturalism and emphasizes stylistic variety. Text is often incorporated into artwork from this period.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Reliquary of Sainte-Foy)

Essential Knowledge:

■There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Middle Ages.

■There is a great influence of Roman, Early Medieval, and Islamic art on Romanesque art.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Bayeux Tapestry)

Essential Knowledge:

■Works of art were often displayed in religious or court settings.

■Existing architecture is mostly religious.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Bayeux Tapestry)

Essential Knowledge:

■The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written record.

■Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

By 1000, Europe had begun to settle down from the great migration that characterized the Early Medieval period. Wandering seafarers like the Vikings were Christianized, and their descendants colonized Normandy, France, and southern Italy and Sicily. Islamic incursions from Spain and North Africa were neutralized; in fact, Europeans began a counterinvasion of Muslim lands called the Crusades. The universal triumph of Christianity in Europe with the pope cast as its leader was a spiritual empire not unlike the Roman secular one.

Even though Europeans fought with equal ardor among themselves, enough stability was reached so that trade and the arts could flourish; cities, for the first time in centuries, expanded. People began to crisscross Europe on religious pilgrimages to Rome and even Jerusalem. The most popular destination was the shrine dedicated to Saint James in the northwestern Spanish town of Santiago de Compostela. A magnificent Romanesque cathedral was built as the endpoint of western European pilgrimages.

The journey to Santiago took perhaps a year or longer to make. Shrines were established at key points along the road, so that pilgrims could enjoy additional holy places, many of which still survive today. This pilgrimage movement, with its consequent building boom, is one of the great revitalizations in history.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Medieval society centered on feudalism, which can be expressed as a symbiotic relationship between lords and peasants. Peasants worked the land, sustaining all with their labor. Lords owned the land, and they guaranteed peasants security. Someplace between these stations, artists lived in what eventually became a middle class. Painting was considered a higher calling compared to sculpture or architecture because painters worked less with their hands.

Women were generally confined to the “feminine arts” such as ceramics, weaving, or manuscript decoration. Powerful and wealthy women (queens, abbesses, and so on) were active patrons of the arts, sponsoring the construction of nunneries or commissioning illuminated manuscripts. Hrotswitha of Gandersheim, a nun, wrote plays that were reminiscent of Roman playwrights and poets. One of the most brilliant people of the period was Hildegard von Bingen, who was a renowned author, composer, and patroness of the arts.

Although Christian works dominate the artistic production of the Romanesque period, a significant number of beautifully crafted secular works also survives. The line between secular and religious works in medieval society was not so finely drawn, as objects for one often contain symbolism of the other.

The primary focus of medieval architecture is on the construction of castles, manor houses, monasteries, and churches. These were conceived not by architects in the modern sense of the word, but by master builders, who oversaw the whole operation from designing the building to contracting the employees. These master builders were often accompanied by master artists, who supervised the artistic design of the building.

ROMANESQUE ARCHITECTURE

Cathedrals were sources of civic pride as well as artistic expression and spiritual devotion. Since they sometimes took hundreds of years to build and were extremely expensive, great care was lavished on their construction and maintenance. Church leaders sought to preserve structures from the threat of fire and moved away from wood to stone roofs. Those that were originally conceived with wood were sometimes retrofitted. This revival of structures entirely in stone is one reason for the period’s name, “Romanesque.”

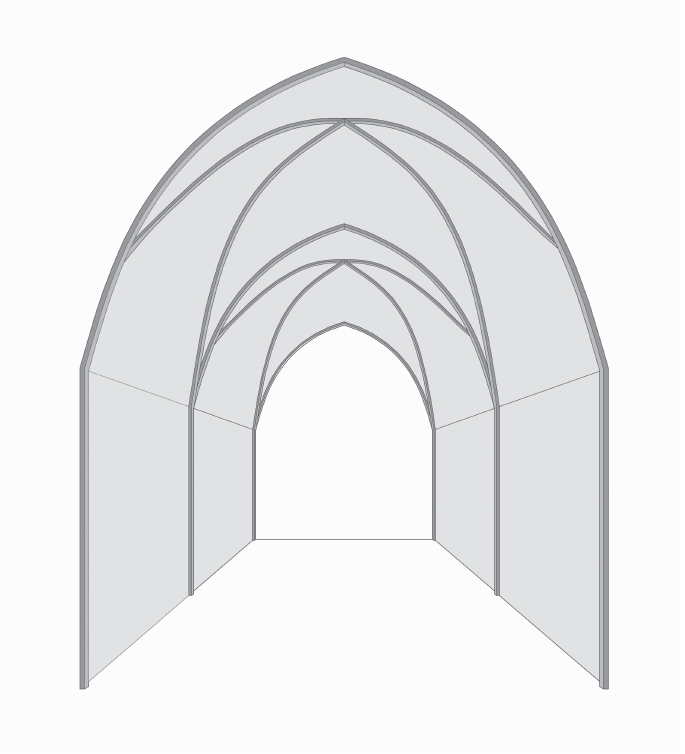

Figure 11.1: Rib vaults

But stone caused problems. It is heavy—which means that the walls have to be extra thick to sustain the weight of the roof. Windows are small, so that there are as few holes in the walls as possible. The interiors are correspondingly dark. To bring more light into the buildings, the exterior of the windows are often narrow and the interior of the window wider—this way the light would come in through the window and ricochet off its thick walls and appear more luminous. However, the introduction of stained glass darkened attempts at lightening the interiors.

To help support the roofs of these massive buildings, master builders designed a new device called the rib vault (Figure 11.1). At first, these ribs were decorative moldings placed on top of groin vaults, but eventually they became a new way of looking at roof support. While they do not carry its full weight, they help channel the stresses of its load down to the walls and onto the massive piers below, which serve as functional buttresses. Rib vaults also open up the ceiling spaces more dramatically, allowing for larger windows to be placed in the clerestory. During construction, rib vaults were the first part of the roof to be built, the stones in the spaces between were added later (Figure 11.1).

Besides the advantage of being fireproof, stone has several other positive properties. It is easy to maintain, durable, and generally weatherproof. It also conducts sound very well, so that medieval music, characterized by Gregorian chant, could be performed, enabling even those in the rear of these vast buildings to hear the service.

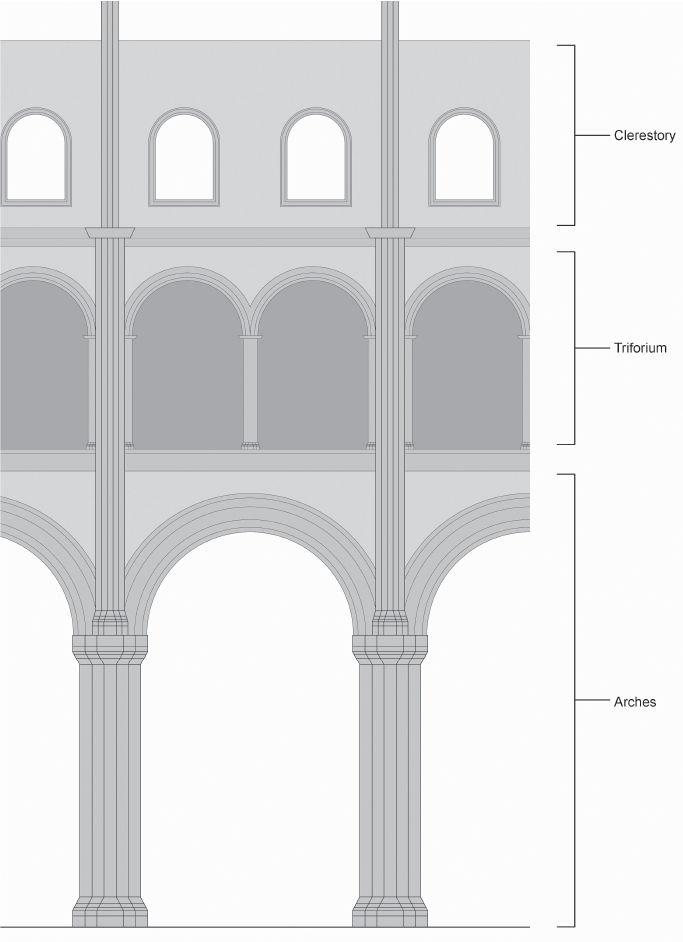

Figure 11.2: A bay is a vertical section of a church often containing arches, a triforium, and a clerestory.

The basic unit of medieval construction is called the bay. This spatial unit contains an arch on the first floor, a triforium with smaller arches on the second, and windows in a clerestory on the third. The bay became a model for the total expression of the cathedral—its form is repeated throughout the building to render an artistic whole (Figure 11.2).

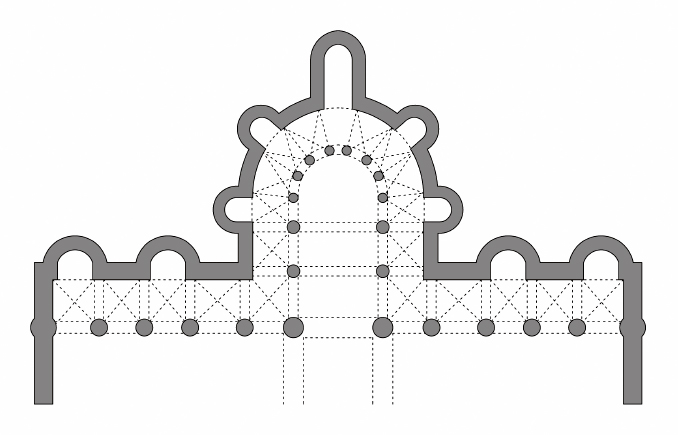

In order to accommodate large crowds who came to Romanesque buildings during feast days or for pilgrimages, master builders designed an addition to the east end of the building, called an ambulatory, a feature that was also present in Early Christian churches. This walkway had the benefit of directing crowds around the church without disturbing the ceremonies taking place in the apse. Chapels were placed at measured intervals around the ambulatory so that pilgrims could admire the displays of relics and other sacred items housed there. The ambulatory at Saint. Sernin (Figure 11.3) is a good example of how they work in this context.

Figure 11.3: An ambulatory is the passageway that winds around an apse. Romanesque buildings often have chapels that radiate from them. Ambulatories can be found in buildings as early as the Early Christian period.

After six hundred years of relatively small buildings, Romanesque architecture with its massive display of cut stone comes as a surprise. The buildings are characterized as being uniformly large, displaying monumentality and solidity. Round arches, often used as arcades, are prominent features on façades. Concrete technology, a favorite of the ancient Romans, was forgotten by the tenth century.

Interiors are dark; façades are sometimes punctured with round oculus-type windows.

Although some buildings were built with wood ceilings, the tendency outside Italy is to use Roman stone-vaulting techniques, such as the barrel and groin vault to cover the interior spaces as at Sainte-Foy (Figure 11.4). However, later buildings employ rib-covered groin vaults to make interiors seem taller and lighter.

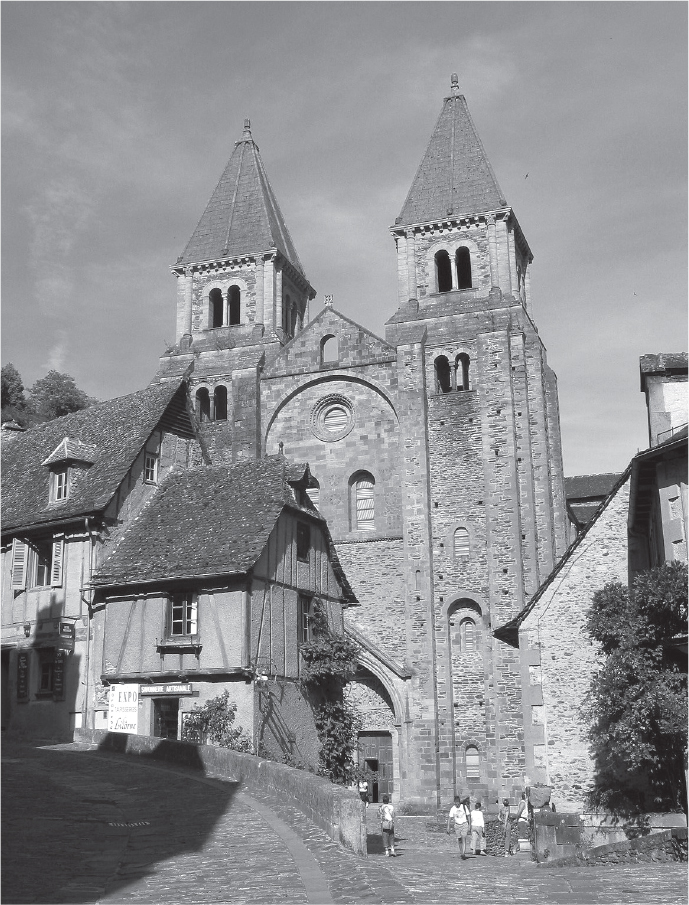

Figure 11.4a: Church of Sainte-Foy, Romanesque Europe, c. 1050–1130, stone, Conques, France

Figure 11.4b: Nave of Church of Sainte-Foy

Italian buildings have separate bell towers called campaniles to summon people to prayer. Northern European buildings incorporate this tower into the fabric of the building often over the crossing.

Church of Sainte-Foy, Romanesque Europe, c. 1050–1130, stone, Conques, France (Figures 11.4a and 11.4b)

Form

■Church built to handle the large number of pilgrims: wide transepts, large ambulatory with radiating chapels.

■Massive heavy interior walls, unadorned.

■No clerestory; light provided by windows over the side aisles and galleries.

■Barrel vaults in nave, reinforced by transverse arches.

■Cross-like ground plan, called a Latin cross.

Function

■Christian church built along the pilgrimage road to Santiago de Compostela, a popular pilgrimage center for the worship of the relics of Saint James.

■Radiating chapels housed relics of the saints.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 58

Web Source https://www.tourisme-conques.fr/en/en-conques/st-foy-abbey-church

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Pilgrimages

–Great Stupa, Sanchi (Figures 23.4a, 23.4b, 23.4c, 23.4d, 23.4e)

–Kaaba (Figures 9.11a, 9.11b)

–Bamiyan Buddha (Figures 23.2a, 23.2b)

ROMANESQUE SCULPTURE AND PAINTING

Large-scale stone sculpture was generally unknown in the Early Medieval period—its revitalization is one of the hallmarks of the Romanesque. Sculptors took their inspiration from goldsmiths and other metal workers, but expanded the scale to almost life-size works. Most characteristically, sculpture was placed around the portals of medieval churches so that worshippers could understand, among other things, the theme of a particular building (Figure 11.5). Small-scale works, such as ivories, wooden objects, and metalwork continued to flourish as they did in earlier periods.

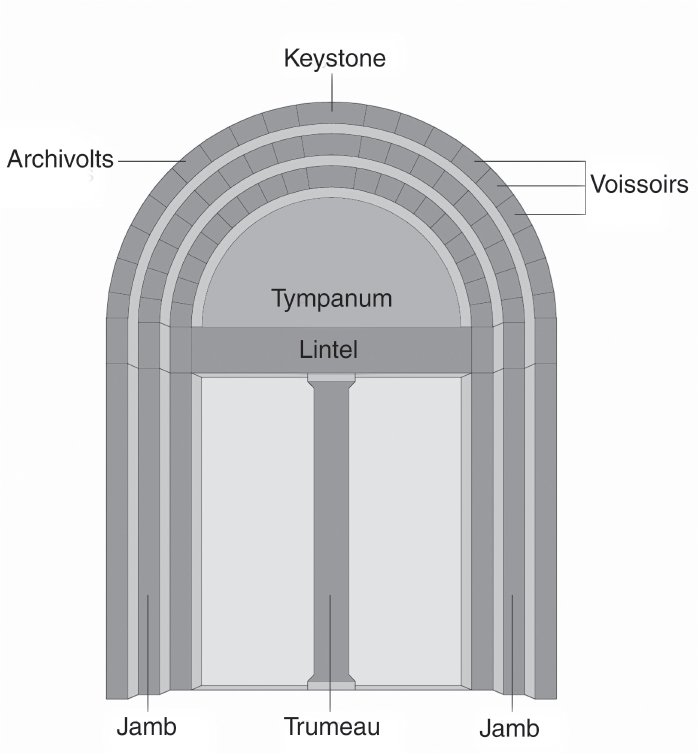

Figure 11.5: A Romanesque portal

Most of what we know about Romanesque painting comes from illuminated manuscripts and an occasional surviving ceiling or wall mural. Characteristically, figures tend to be outlined in black and then vibrantly colored. Gestures are emphatic; emotions are exaggerated—therefore, heads and hands are proportionally the largest features. Figures fill a blank surface rather than occupy a three-dimensional reality; hence they seem to float. Sometimes they are on tiptoe or glide across a surface, as they do in the Bayeux Tapestry. People are most important; they dominate buildings that seem like props or stage sets in the background of most Romanesque illustrations.

Painted stone sculpture is a trademark of Romanesque churches. Capitals are elaborately, and often fancifully, carved with scenes from the Bible. The chief glory of Romanesque sculpture is the portal. These are works of so prominent a location that sculptors vied for the honor of carving in so important a site. As artists became famous for their work, towns competed to hire them. Some have prominently placed signatures that proclaim their glory.

Although there are regional variations, there are some broad characteristics that generally define Romanesque sculpture. Figures tend to have a flattened look with zigzagging drapery that often hides body form rather than defines it. Scale is carefully articulated, with a hierarchy of figures being presented according to their importance. Figures are placed within borders, usually using them as isolated frames for scenes to be acted out in. They rarely push against these frames, preferring to be defined by them.

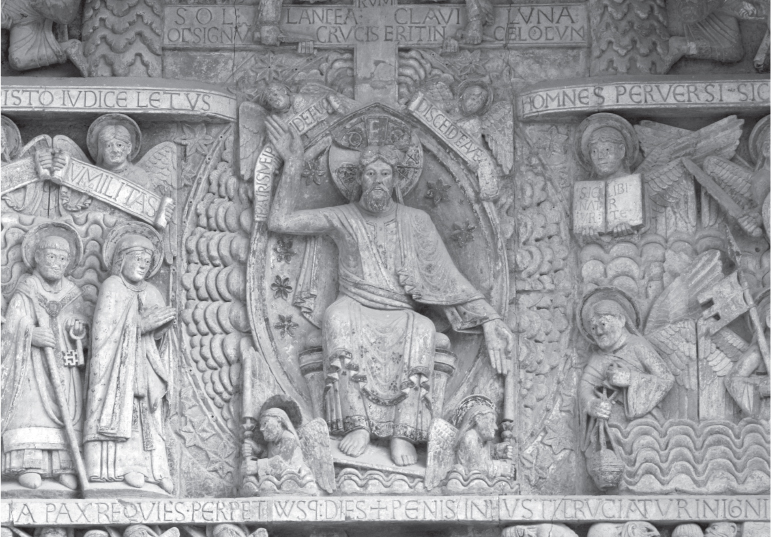

Figure 11.6a: Last Judgment, 1050–1130, stone and paint, Sainte-Foy, Conques

Smaller, independent sculptures were also produced at this time. Among the most significant are reliquaries (Figure 11.6c) that contain venerated objects, like the bones of saints; they are richly adorned and highly prized.

Figure 11.6b: Detail of 11.6a

Last Judgment, 1050–1130, stone and paint, Sainte-Foy, Conques (Figures 11.6a and 11.6b)

Form

■Largest Romanesque tympanum.

■124 figures densely packed together; originally richly painted.

Function

■Last Judgment cautions pilgrims that life is transitory and one should prepare for the next life.

■Subject of the tympanum reminds pilgrims of the point of their pilgrimage.

Content

■Christ, as a strict judge, divides the world into those going to heaven and those going to hell.

–Christ is depicted with a welcoming right hand, a cast down left hand.

–Christ sits in a mandorla.

■A dividing line runs vertically through the cross in the middle of the composition.

■The Archangel Michael and the devil are at Christ’s feet, weighing souls.

■Hell, with the damned, is on the right.

■People enter the church on the right as sinners and exit on the left as saved; the right door has sculptures of the damned and the left door has images of the saved.

■The figures of the saved move toward Christ, Mary, and Saint Peter; local abbots and monks follow Charlemagne, the legendary benefactor of the monastery, who is led by the hand.

■Paradise, at the lower level, is portrayed as the heavenly Jerusalem.

■Sainte Foy interceded for those enslaved by the Muslims in Spain—she herself appears kneeling before a giant hand of God.

■On the right lower level, the devil presides over a chaotic tangle of tortured condemned sinners.

■Inscription on lintel: “O Sinners, change your morals before you might face a cruel judgment.”

■Hieratic scale may parallel one’s status in a feudal society.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 58

Web Source https://www.tourisme-conques.fr/en/en-conques/the-tympanum

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Last Judgment Scenes

–Giotto, Arena Chapel (Figure 13.1b)

–Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel (Figure 16.2e)

–Last judgment of Hunefer (Figure 3.12)

Figure 11.6c: Reliquary of Sainte-Foy, gold, silver, gemstones, and enamel over wood, 9th century with later additions, Sainte-Foy, Conques

Reliquary of Sainte-Foy, gold, silver, gemstones, and enamel over wood, 9th century, with later additions, Sainte-Foy, Conques (Figure 11.6c)

Form

■Child saint’s skull is housed in the rather mannish-looking enlarged head.

■Jewels, gems, and crown added over the years by the faithful, as acts of devotion.

■Facial expression is haughty and severe.

Function

■Reliquary of a young girl martyred in the early fourth century.

Context

■Sainte Foy (or Faith) probably died as a martyr to the Christian faith during the persecutions in 303 under Emperor Diocletian; she was tortured over a brazier; she refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods in a pagan ritual.

■Saint Foy, triumphant over death, looking up and over the viewer’s head.

■Relics of her body were stolen from a nearby town and enthroned in Conques in 866.

■One of the earliest large-scale sculptures in the Middle Ages.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 58

Web Source https://www.tourisme-conques.fr/en/en-conques/the-treasure

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Art as a Container

–Reliquary guardian figure (Figure 27.13)

–Great Stupa (Figure 23.4a)

–Nkisi n’kondi (Figure 27.6)

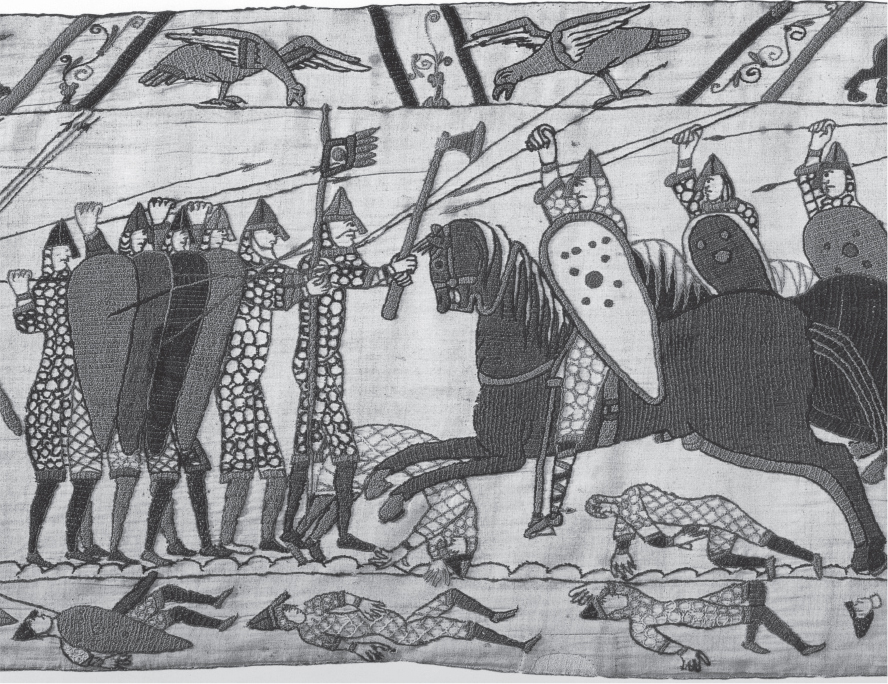

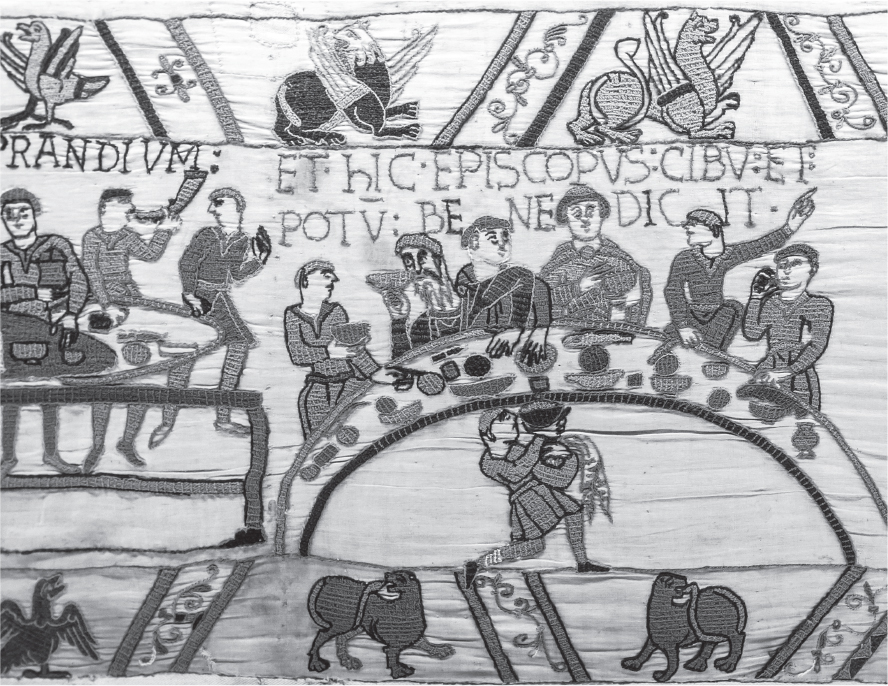

The Bayeux Tapestry, Romanesque Europe (English or Norman), 1066–1080, embroidery on linen, Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Bayeux, France (Figures 11.7a and 11.7b)

Figure 11.7a: Cavalry attack from the Bayeux Tapestry, Romanesque Europe (English or Norman), c. 1066–1080, embroidery on linen, Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Bayeux, France

Figure 11.7b: First meal from the Bayeux Tapestry

Form

■Color used in a decorative, although unnatural, manner—different parts of a horse are colored variously.

■Neutral background of unpainted fabric.

■Flat figures; no shadows.

Content

■Tells the story (in Latin) of William the Conqueror’s conquest of England at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

■The story, told from the Norman point-of-view, emphasizes the treachery of Harold of England, who breaks his vow of loyalty and betrays William by having himself crowned.

■More than 600 people, 75 scenes.

■Fanciful beasts in upper and lower registers.

■Borders sometimes comment on the main scenes or show scenes of everyday life (bird hunting, farming, even pornography).

Function

■Uncertainty over how this work was meant to be displayed, perhaps in a cathedral hung from the pillars in the nave or hung in a hall along a wall.

Technique

■Tapestry is a misnomer; actually, it’s an embroidery.

■Probably designed by a man and executed by women.

Patronage

■Commissioned by Bishop Odo, half-brother to William the Conqueror.

Context

■Continues the narrative tradition of medieval art; 230 feet long.

■Narrative tradition goes back to the Column of Trajan (Figure 6.16).

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 59

Web Source http://www.bayeuxmuseum.com/en/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Battle Scenes

–Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus (Figure 6.17)

–Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace (Figures 25.3a, 25.3b)

–Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (Figure 20.4)

VOCABULARY

Abbey: a monastery for monks, or a convent for nuns, and the church that is connected to it (Figure 11.4a)

Ambulatory: a passageway around the apse of a church (Figure 11.3)

Apse: the end point of a church where the altar is (Figure 11.3)

Arcade: a series of arches supported by columns. When the arches face a wall and are not self-supporting, they are called a blind arcade

Archivolt: a series of concentric moldings around an arch (Figure 11.5)

Axial plan (Basilican plan, Longitundinal plan): a church with a long nave whose focus is the apse, so-called because it is designed along an axis (Figure 11.4b)

Baptistery: in medieval architecture, a separate chapel or building generally in front of a church used for baptisms

Bay: a vertical section of a church that is embraced by a set of columns and is usually composed of arches and aligned windows (Figure 11.2)

Campanile: a bell tower of an Italian building

Cathedral: the principal church of a diocese, where a bishop sits

Clerestory: the window story of a church (Figure 11.2)

Compound pier: a gathering of engaged shafts around a pier (Figure 11.4b)

Continuous Narrative: a work of art that contains several scenes of the same story painted or sculpted in continuous succession (Figures 11.7a and 11.7b)

Embroidery: a woven product in which the design is stitched into a premade fabric (Figures 11.7a and 11.7b)

Gallery: a passageway inside or outside a church that generally is characterized by having a colonnade or arcade (Figure 11.4b)

Jamb: the side posts of a medieval portal (Figure 11.5)

Last Judgment: in Christianity, the judgment before God at the end of the world (Figure 11.6a)

Mandorla: (Italian for “almond”) an almond-shaped circle of light around the figure of Christ or Buddha (Figure 11.6a)

Narthex: the vestibule, or lobby, of a church

Portal: a doorway. In medieval art they can be significantly decorated (Figure 11.5)

Radiating chapel: a chapel that extends out in a radial pattern from an apse or an ambulatory (Figure 11.3)

Reliquary: a vessel for holding a sacred relic. Often reliquaries took the shape of the objects they held. Precious metals and stones were the common material (Figure 11.6c)

Rib vault: a vault in which diagonal arches form riblike patterns. These arches partially support a roof, in some cases forming a web-like design (Figure 11.1)

Tapestry: a woven product in which the design and the backing are produced at the same time on a device called a loom

Transept: an aisle in a church perpendicular to the nave

Transverse arch: an arch that spans an interior space connecting opposite walls by crossing from side to side (Figure 11.4b)

Triforium: A narrow passageway with arches opening onto a nave, usually directly below a clerestory (Figure 11.2)

Trumeau (plural: trumeaux): the central pillar of a portal that stabilizes the structure. It is often elaborately decorated (Figure 11.5)

Tympanum (plural: tympana): a rounded sculpture placed over the portal of a medieval church (Figure 11.6a)

Vault: a roof constructed with arches; when an arch is extended in space, forming a tunnel, it is called a barrel vault; when two barrel vaults intersect at right angles, it is called a groin vault

Voussoir (pronounced “vōō-swar”): a wedge-shaped stone that forms the curved part of an arch. The central voussoir is called a keystone (Figure 11.5)

SUMMARY

In a way, the monumentality, rounded arches, and heavy walls of Roman architecture are reflected in the Romanesque tradition. However, the liturgical purpose of Romanesque buildings, their use of ambulatories and radiating chapels and their dark interiors give these churches a religious feeling quite different from their Roman predecessors.

Romanesque builders reacted to the increased mobility of Europeans, many of whom were now traveling on pilgrimages, by enlarging the size of their buildings. As Romanesque art progresses, increasingly sophisticated vaulting techniques are developed. Hallmarks of the Romanesque style include thick walls and piers that give the buildings a monumentality and massiveness lacking in Early Medieval art.

Most great Romanesque sculpture was done around the main portals of churches, usually on themes related to the Last Judgment and the punishment of the bad alongside the salvation of the good. French sculptors carved energetic and elongated figures that often look flattened against the surface of the stone. Although regional variations are common, most Romanesque sculpture is content within the frame of the work it is conceived in, and rarely presses against the sides or emerges forward.

Although religious themes dominate Romanesque art, occasionally works of secular interest, like the Bayeux Tapestry, were created.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.The subject matter in the Bayeux Tapestry is most similar to

(A)scenes from the Vienna Genesis

(B)the Temple of Zeus and Athena at Pergamon

(C)the Niobides Krater

(D)the Column of Trajan

2.Pilgrims entering Romanesque churches such as Sainte-Foy were expected to

(A)walk to the chapels in the rear where the relics were housed

(B)worship around a centrally planned altar where services would be held

(C)travel to the top of the bell towers to ceremonially ring the bells

(D)place offerings at the foot of a statue of Jesus

3.The scene over the doorway of the Church of Sainte-Foy of the Last Judgment shows the damned condemned to hell on the right and the saved rising to heaven on the left because

(A)in the middle are those who were noncommittal about religion and salvation

(B)one enters the church as a sinner on the right but emerges saved on the left

(C)in the Christian tradition, the damned are unwelcome in church

(D)a parallel is drawn between sinners who must use the right door and saints who must use the left door

4.The Reliquary of Sainte-Foy and the Reliquary Figure (byeri) are similar in that they

(A)are both meant to ward off evil

(B)are both male figures in the shape of females

(C)both held skulls of important deceased people

(D)are both part of an extensive pilgrimage site for many to come to

5.Romanesque architecture can be characterized as

(A)small, intimate, and warm

(B)soaring, vertical, and uplifting

(C)thick, heavy, and massive

(D)irregular, unbalanced, and asymmetrical

Short Essay

Practice Question 4: Contextual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

This is the Romanesque church at Sainte-Foy.

Why was this church built?

Discuss how the design of this church reflects its symbolic and practical functions.

Analyze how at least two contextual elements contributed to a religious experience for medieval Christians.

ANSWER KEY

1.D

2.A

3.B

4.C

5.C

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(D) Both the Bayeux Tapestry and the Column of Trajan have narrative retellings of real historical events.

2.(A) Pilgrims treasured seeing relics of the saints, which were placed in chapels in the ambulatory around the altar of a church.

3.(B) One enters the church a sinner and leaves absolved of sins.

4.(C) Both reliquary figures hold skulls. The Sainte-Foy holds one within the head of the saint; the Reliquary Figure holds one in a container he is resting on.

5.(C) Romanesque architecture is thick, heavy, and massive, and often very dark.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Why was this church built? |

1 |

Answers could include: ■To house the relics of Sainte-Foy. ■To be a pilgrimage site along the road to Santiago de Compostela. |

Discuss how the design of this church reflects its symbolic and practical functions. |

1: symbolic function 1: practical function |

Answers could include: ■Church is nestled amid other buildings downtown, symbolically mixing with the people. ■Long nave, wide transept, and ambulatory used to accommodate large numbers of pilgrims. ■Long nave used for processions. ■Large ambulatory around the altar allows for a free flow of pilgrims to the various chapels, and relics on display. ■Cross-like ground plan reflects the crucifixion of Jesus. |

Analyze how at least two contextual elements contributed to a religious experience for medieval Christians. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■Lack of nave windows contributes to a dark interior, which symbolizes the mysteries of the Christian faith. ■Sculpture on the façade of the Last Judgment warns pilgrims of the dangers of hell and encourages them toward salvation. ■Stone walls enhance the echo effect that characterized medieval chanting. |