Content Area: Ancient Mediterranean, 3500 B.C.E.–300 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: 3000–30 B.C.E.

The most relevant artistic periods in Egyptian art are the following:

| Old Kingdom | 2575–2134 B.C.E. |

| New Kingdom | 1550–1070 B.C.E. |

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

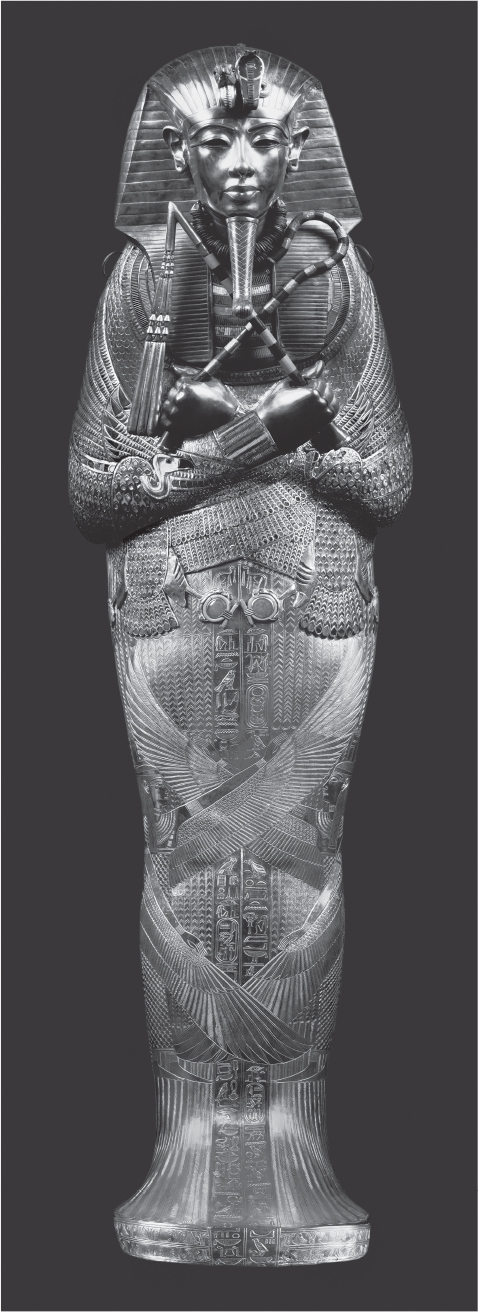

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: the Innermost coffin of King Tutankhamun)

Essential Knowledge:

■Egyptian art expresses the ideas of permanence, rebirth, and eternity.

■Egyptian figure styles follow a formula that expresses differences in status.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Temple of Amun-Re)

Essential Knowledge:

■Egyptians developed the use of the clerestory to provide light into darkened interiors.

■The god-king is expressed in monumental stone structures that Egypt has become famous for.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Great Pyramids of Giza)

Essential Knowledge:

■There are many similarities among artistic styles in Egypt, which indicates a vibrant exchange of ideas.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

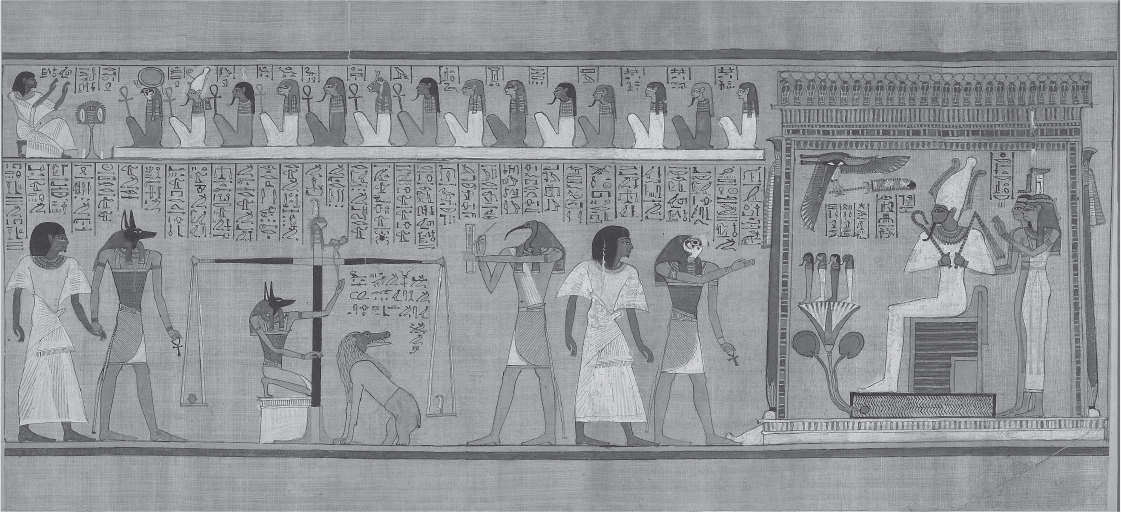

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Last judgment of Hunefer)

Essential Knowledge:

■Egyptian art is sometimes centered on elaborate funerary practices and the numerous artifacts associated with them.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Palette of King Narmer)

Essential Knowledge:

■The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Egypt gives the appearance of being a monolithic civilization whose history stretches steadily into the past with little change or fluctuation. However, Egyptian history is a constant ebb and flow of dynastic fortunes, at times at the height of its powers, other times invaded by jealous neighbors or wracked by internal feuds.

Historical Egypt begins with the unification of the country under King Narmer in predynastic times, an event or a series of events celebrated on the Narmer Palette (3000–2920 B.C.E.) (Figure 3.4). The subsequent early dynasties, known as the Old Kingdom, featured massively built monuments to the dead, called pyramids, which are emblematic of Egypt today.

After a period of anarchy, Mentihotep II unified Egypt for a second time in a period called the Middle Kingdom. Pyramid building was abandoned in favor of smaller and less expensive rock-cut tombs.

More anarchy followed the breakdown of the Middle Kingdom. Invaders from Asia swept through, bringing technological advances along with their domination. Soon enough, Egyptians righted their political ship, removed the foreigners, and embarked upon the New Kingdom, a period of unparalleled splendor.

One New Kingdom pharaoh, Akhenaton, markedly altered Egyptian society by abandoning the worship of the many gods and substituting one god, Aton, with himself portrayed as his representative on Earth. Aton was different from prior Egyptian gods because he was represented as a sun disk emanating rays, instead of gods that were human and/or animal symbols. This new religion ushered in a dramatic change in artistic style called the Amarna period. Although Akhenaton’s religious innovations did not survive him, the artistic changes he promoted were long lasting.

After the demise of the New Kingdom, Egypt felt prey to the ambitions of Persia, Assyria, and Greece, ultimately undoing itself at the hands of Rome in 30 B.C.E.

Modern Egyptology began with the 1799 discovery of the Rosetta Stone, from which hieroglyphics could, for the first time, be translated into modern languages. Egyptian paintings and sculpture, often laden with text, could now be read and understood.

The feverish scramble to uncover Egyptian artifacts culminated in 1922 with the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter. This is one of the most spectacular archaeological finds in history because it is the only royal Egyptian tomb that has come down to us undisturbed.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Egyptian architecture was designed and executed by highly skilled craftsmen and artisans, not by slaves, as tradition often alleges. The process of mummification, which became a national industry, was handled by embalming experts who were paid handsomely for their exacting and laborious work.

Most artists like Imhotep, history’s first recorded artist, should more properly be called artistic overseers, who supervised all work under their direction. They were likely ordained high priests of Ptah, the god who created the world in Egyptian mythology.

As the royal builder for King Djoser, Imhotep erected the first and largest pyramid ever built, the Stepped Pyramid. Indeed, Imhotep’s reputation as a master builder so fascinated later Egyptians that he was deified and worshipped as the god of wisdom, astronomy, architecture, and medicine. Few other Egyptian artists’ names come down to us.

EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE

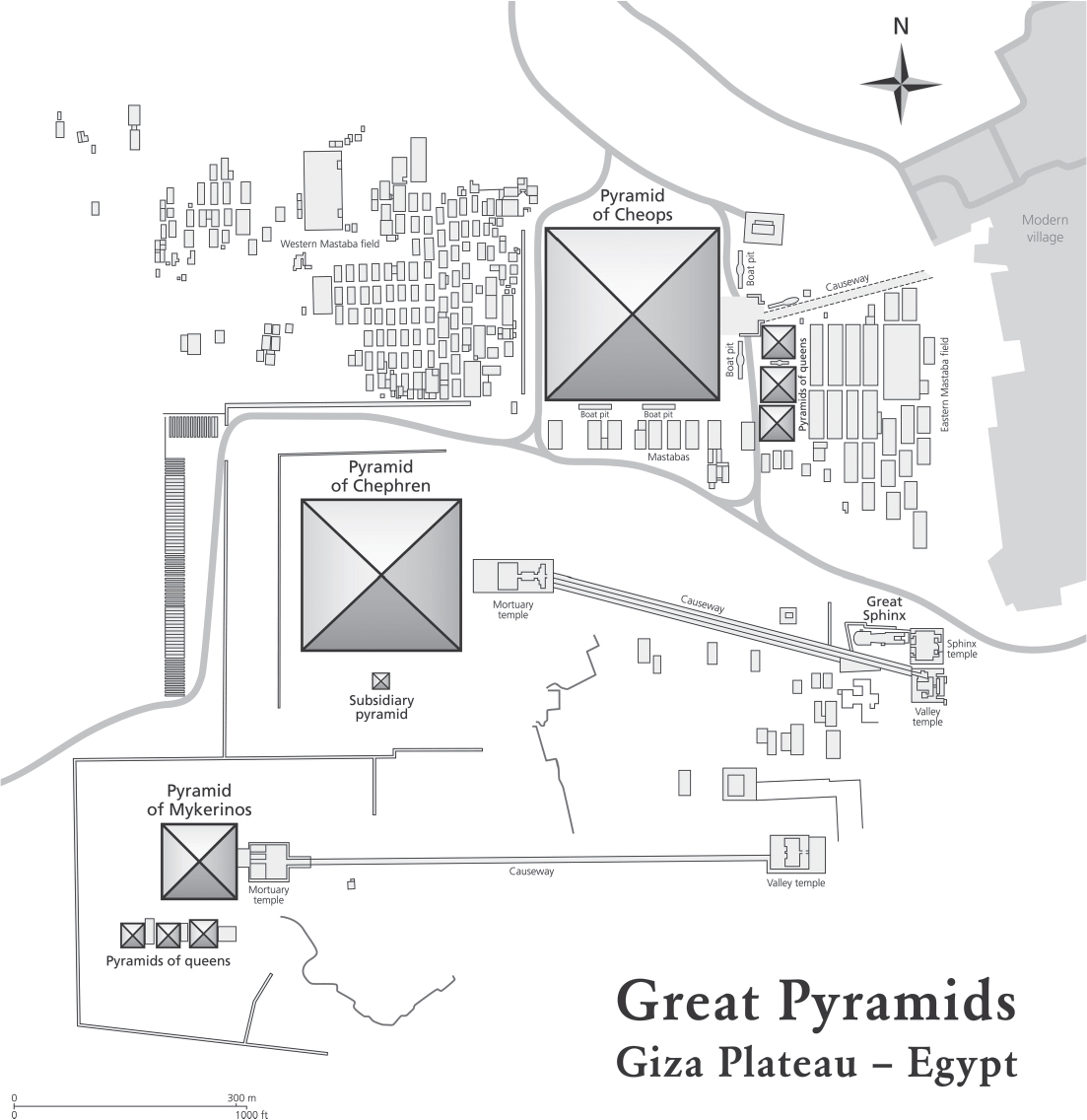

The iconic image of Egyptian art is the pyramid, sitting as it does adrift in the sands of the Sahara. Pyramids were never built alone but as part of great complexes, called necropolises, dedicated to the worship of the spirits of the dead and the preservation of an individual’s ka, or soul.

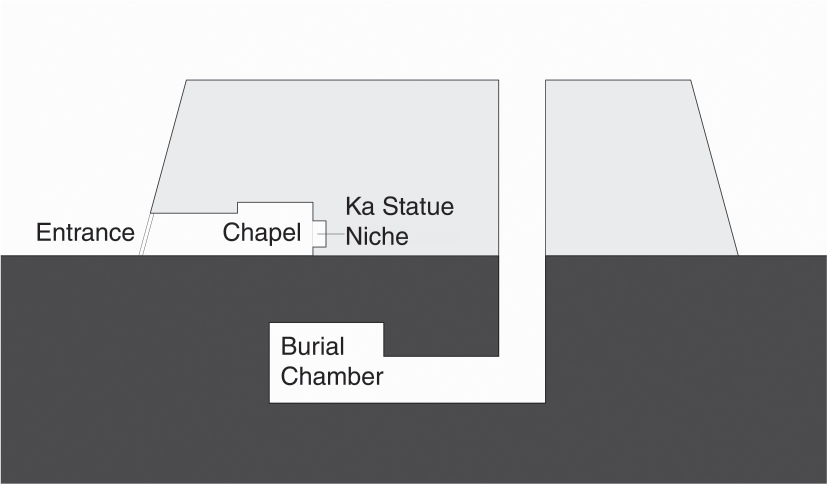

At first, Egyptians buried their dead in more unassuming places called mastabas (Figure 3.1). A mastaba is a simple tomb that has four sloping sides and an entrance for mourners to bring offerings to the deceased. The body was buried beneath the mastaba in an inaccessible area that only the spirit could enter.

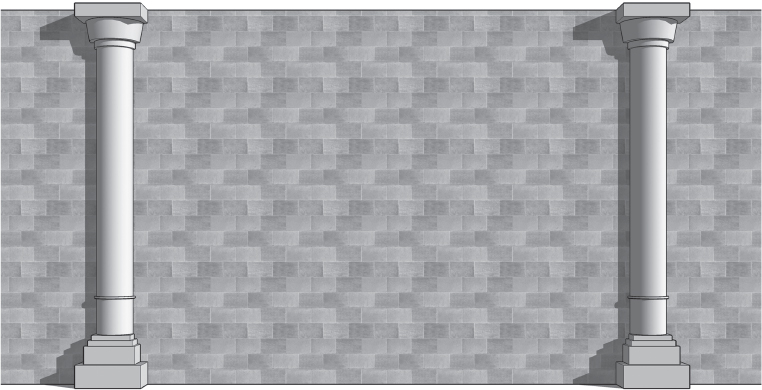

Later rulers with grander ambitions began to build larger monuments, heaping the mastaba form one atop the other in smaller dimensions until a pyramid was achieved. The first such example of this is the Stepped Pyramid of King Djoser. Imhotep’s complex included temples with engaged columns (Figure 3.2).

After several experiments with the pyramid form, the archetypal pyramids such as the ones at Giza (Figure 3.6) evolved with sleek prismatic surfaces. Interiors included false doors so that the ka could come and go when summoned by the faithful.

An Egyptian specialty is carving from living rock. Huge monuments such as the Great Sphinx (c. 2500 B.C.E.) (Figure 3.6a) were hewn from a single great rock; tombs like those at Beni Hasan were carved into hillsides, hollowing out chambers filled with reserve columns.

Figure 3.1: Sectional diagram of a mastaba

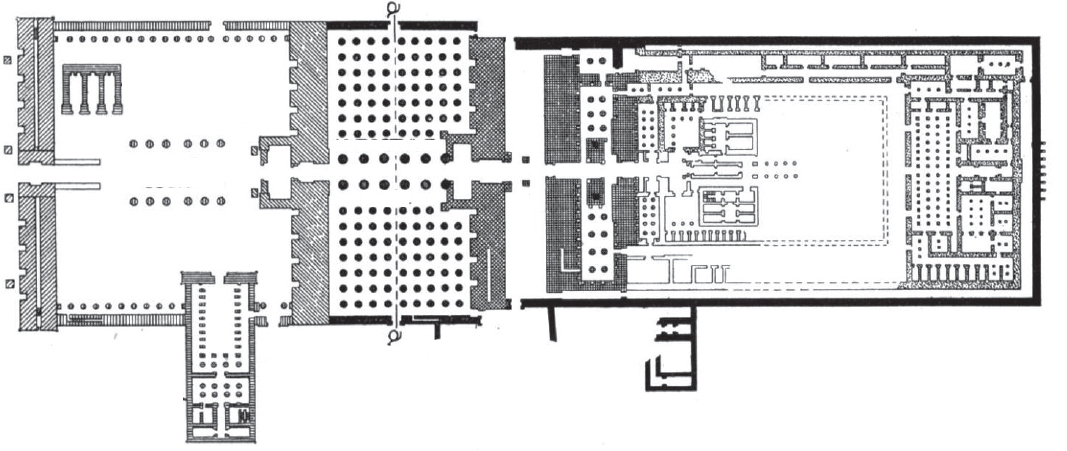

In the New Kingdom, temples continued to be built into the sides of rock formations, as at Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple (1473–1458 B.C.E.) (Figure 3.9a). However, this period also produced freestanding monuments as at Luxor (Figure 3.8a), which had massive pylons on the outside protecting the sanctuary. Behind the pylons lay a central courtyard that greeted the worshipper. The god was housed in a sacred area just beyond, which was surrounded by a forest of columns, called a hypostyle hall. Some of the columns were higher than others, allowing limited light and air to enter the complex. This upper area is called a clerestory. In a sanctuary submerged in the half-light of the closely placed columns, the god was sheltered so completely that only the high priest or the pharaoh could enter.

Figure 3.2: Engaged columns

Egyptian pyramids are known for their sleek solid surfaces and their monumental scale. They are made from stone blocks and built without mortar. Once the dead were interred, no one was permitted entry into these sealed structures. The sides of the pyramids are oriented to the four cardinal points of the compass. The benben (coming from a root meaning to “swell up”) was a pyramid-like stone at Heliopolis, Egypt, which formed the prototype for the capstone of the pyramids and/or the pyramids themselves. Pyramid Texts, the oldest religious texts in existence, confirm that the pharaoh’s body could be reenergized after death and ascend to the heavens using ramps, stairs, or ladders. He could even become airborne.

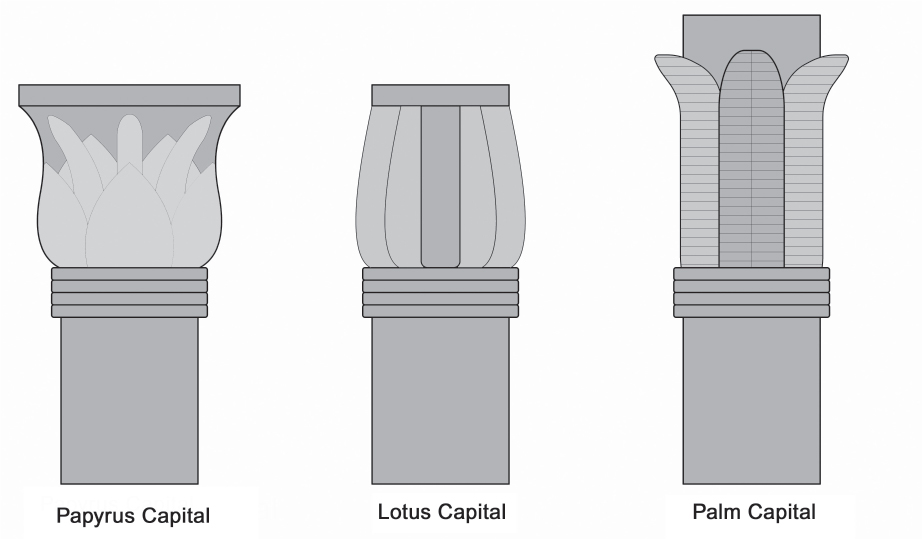

Figure 3.3: Papyrus, lotus, and palm capitals

The pyramids do not exist in isolation, but are part of a vast temple complex that was strictly organized. The complexes are on the west side of the Nile, so that the pharaoh was interred in the direction of the setting sun. The temples are on the east side of the pyramids, facing the rising sun. Like the pyramids, most Egyptian temples have an astronomical orientation.

Columns used in New Kingdom temples were based on plant shapes: the lotus, the palm, and the papyrus. These column types reflected early construction methods done at a time when Egyptian buildings were supported by perishable materials (Figure 3.3).

EGYPTIAN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE

The monumentality of stone sculpture, unseen in ancient Sumeria, is new to art history. Even Egyptian sarcophagi were hewn from enormous stones and placed in tombs to protect the dead from vandals.

Hieroglyphics describe the deceased and his or her accomplishments in great detail, without which the dead would have incomplete afterlives. Writing appears both on relief sculpture and on sculpture in the round, as well as on a paper surface called papyrus. Hieroglyphics help modern Egyptologists rediscover some of the original intentions of works of art.

Egyptians believed superhuman forces were constantly at work and needed continuous worship. Egyptian funerary art was dedicated to the premise that things that were buried were to last forever and that this life must continue uninterrupted into the next world. To that end, artists affirmed this belief by representing the human figure as completely as possible.

The Egyptian canon of proportions allows for little individuality. Shoulders are seen frontally, while the rest of the body, except the eye, is turned in profile. Often, heads face one direction while the legs face another. Men are taller than women and are painted a ruddy brown or red. Women are shorter—children shorter still—and are painted with a yellowish tinge. Shading is rare.

The ideal is to represent successful men and women acting in a calm, rational manner. Episodes of violence and disorder are limited only to scenes of slaughtering animals for sacrifices or overthrowing the forces of evil; otherwise, Egyptian art is a picture of contentment and stability.

Figures rest on a ground line often at the front of the picture plane. When figures are placed on a line above in a register, they are thought to be receding into the distance.

Because Egyptians believed in a canon of proportions, artists placed a grid over the areas to be painted and outlined the figures accordingly. Unfinished figures rendered the subject’s existence incomplete in the afterlife. Even animals had to be drawn as completely as possible.

In the Amarna period there is a general relaxation of canon rules. Figures are depicted as softer, with slack jaws and protruding stomachs over low-lying belts. Arms become thinner and limbs more flexible, as in the sculpture of Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and three daughters (Figure 3.10) in the fourteenth century B.C.E.

Egyptian sculpture ranges in size from the most intimate pieces of jewelry to some of the largest stone sculptures ever created. Huge portraits of the pharaohs are meant to impress and overwhelm; individualization and sophistication are sacrificed for monumentality and grandeur. The stone of choice is limestone from Memphis. Other stones, like gypsum and sandstone, are also used, but hard stones like granite are avoided when possible because of the difficulty in carving with soft metal tools. Wooden sculpture is painted unless made of exceptionally fine material. Metal sculptures of copper and iron also exist.

Large-scale sculptures are rarely entirely cut free of the rock they were carved from. For example, Menkaura and queen (c. 2490–2472 B.C.E.) (Figure 3.7) has the legs attached to the front of the throne, making the figures seem more permanent and solid. Colossal sculptures, like the Great Sphinx, are carved on the site, or in situ, from the local available rock.

Relief sculptures follow the same figural formula as paintings. When relief sculptures are carved for outdoor display, they are often cut into the rock so that shadows showed up more dramatically, and the figures thereby become more visible. When carved indoors, reliefs are raised from the surface for visibility in a dark interior.

Palette of King Narmer, predynastic Egypt, 3000–2920 B.C.E., graywacke, Egyptian Museum, Cairo (Figures 3.4a and 3.4b)

Form

■Hierarchy of scale.

■Figures stand on a ground line.

■Narrative.

■Schematic lines delineate Narmer’s muscle structure: forearm veins and thigh muscles are represented by straight lines, the kneecaps by half circles.

■Composite view of the human body: mostly seen in profile, but chest, eye, and ear are frontal.

■Hieroglyphics explain and add to the meaning, and they identify Narmer in the cartouche.

Function

■Palette used to prepare eye makeup for the blinding sun, although this palette was probably commemorative.

■Palettes carved on two sides were for ceremonial purposes.

Figures 3.4a and 3.4b: Palette of King Narmer, predynastic Egypt, 3000–2920 B.C.E., graywacke, Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Content

■Relief sculpture depicting King Narmer uniting Upper and Lower Egypt.

■Depicted four times at the top register is Hathor, a god as a cow with a woman’s face, or Bat, a sky goddess who has the power to see the past and the future, or a bull which symbolizes the power and strength of the king.

■On the front:

–Narmer, who is the largest figure, wears the cobra crown of Lower Egypt and is reviewing the beheaded bodies of the enemy; the bodies are seen from above, the heads carefully placed between their legs.

–Narmer is preceded by four standard bearers and a priest; his foot washer or sandal bearer follows.

–In the center, mythical animals with elongated necks are harnessed, possibly symbolizing unification; at the bottom is a bull knocking down a city fortress—Narmer knocking over his enemies.

■On the back:

–The falcon is Horus, god of Egypt, who triumphs over Narmer’s foes; Horus holds a rope around a man’s head and a papyrus plant, symbols of Lower Egypt.

–Narmer has a symbol of strength, the bull’s tail, at his waist; wears a bowling-pin-shaped crown as king of united Egypt, beating down an enemy. (This refers to a smiting pose seen in Egyptian predynastic works.)

–A servant behind Narmer holds his sandals as he stands barefoot on the sacred ground as a divine king.

–Defeated Egyptians lie beneath his feet.

Theories

■Represents the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under one ruler.

■Unification is expressed as a concept or goal to be achieved.

■May represent a balance of order and chaos.

■May reference the journey of the sun god.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 13

Web Source https://www.ancient.eu/Narmer_Palette/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Interpreting Symbols

–Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (Figure 20.4)

–Cotsiogo, Hide Painting of a Sun Dance (Figure 26.13)

–Frontispiece of the Codex Mendoza (Figure 18.1)

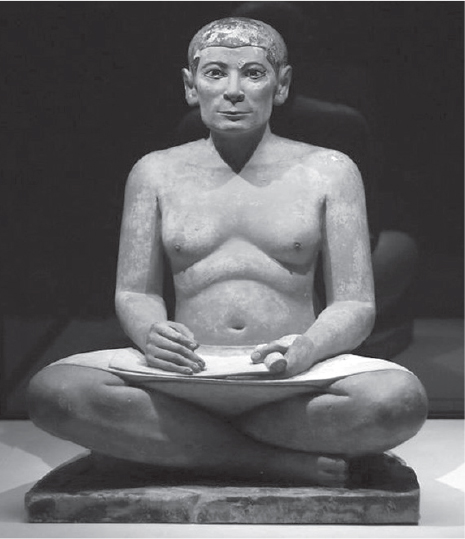

Seated scribe, Saqqara, Egypt, c. 2620–2500 B.C.E., Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, painted limestone, Louvre, Paris (Figure 3.5)

Form

■Not a pharaoh: sagging chest and realistic body rather than the idealistic features reserved for a pharaoh; the scribe contrasts with the ideally portrayed pharaoh.

■Figure has high cheekbones, hollow cheeks, and a distinctive jaw line.

■Meant to be seen from the front.

■Color still remains on the sculpture.

Function

■Created for a tomb at Saqqara as a provision for the ka.

Content

■Amazingly lifelike but not a portrait—rather, it’s a conventional image of a scribe.

■Inlaid crystal eyes.

■Holds papyrus in his lap; his writing instrument (now gone) was in his hand ready to write.

Figure 3.5: Seated scribe, Saqqara, Egypt, c. 2620–2500 B.C.E., Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, painted limestone, Louvre, Paris

Figure 3.6a: Great Pyramids (Menkaura, Khafre, and Khufu) and the Great Sphinx, c. 2550–2490 B.C.E., Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, cut limestone, Giza, Egypt

Context

■Attentive expression; thin angular face; in readiness for the words the pharaoh might dictate.

■Seated on the ground to indicate his comparative low station.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 15

Web Source http://musee.louvre.fr/oal/scribe/indexEN.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Human Figure

–Shiva as Nataraja (Figure 23.6)

–Great Buddha from Todai-ji (Figure 25.1b)

–Abakanowicz, Androgyne III (Figure 29.7)

Great Pyramids (Menkaura, Khafre, and Khufu), c. 2550–2490 B.C.E., Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, cut limestone, Giza, Egypt (Figures 3.6a and 3.6b)

Form

■Each pyramid is a huge pile of limestone with a minimal interior that housed the deceased pharaoh.

■Each pyramid had an enjoining mortuary temple used for worship.

Function

■Giant monuments to dead pharaohs: Menkaura, Khufu, and Khafre.

■Preservation of the body and tomb contents for eternity.

■Some scholars also suggest that the complex served as the king’s palace in the afterlife.

Figure 3.6b: Plan of the pyramid field

Context

■Each pyramid has a funerary complex adjacent connected by a formal pathway used for carrying the dead pharaoh’s body to the pyramid to be interred.

■Shape may have been influenced by a sacred stone relic called a benben, which is shaped like a sacred stone found at Heliopolis. Heliopolis was the center of the sun god cult.

■Each side of the pyramid is oriented toward a point on the compass, a fact pointing to an association with the stars and the sun.

■Giza temples face east, the rising sun, and have been associated with the god Re.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 17

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/86

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Commemoration of Ruler and Country

–Taj Mahal (Figures 9.17a, 9.17b)

–Houdon, George Washington (Figure 19.7)

–Terra cotta warriors (Figures 24.8a, 24.8b)

Great Sphinx, c. 2500 B.C.E., limestone, Giza, Egypt (Figure 3.6a)

Form

■Carved in situ from a huge rock; colossal scale.

■Body of a lion, head of a pharaoh and/or god.

■Originally brightly painted to stand out in the desert behind the figure, which once rose near ramps rising from the Nile.

Function

■The Sphinx seems to be protecting the pyramids behind it, although this theory has been debated.

Context and Interpretation

■Very generalized features, although some say it may be a portrait of Khafre.

■Cats are royal animals in ancient Egypt, probably because they saved the grain supply from mice.

History

■Head of the Sphinx badly mauled in the Middle Ages.

■Fragment of the Sphinx’s beard is in the British Museum.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 17

Web Source https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA58

King Menkaura and queen, Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, 2490–2472 B.C.E., graywacke, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Figure 3.7)

Form

■Two figures attached to a block of stone; arms and legs not cut free.

■Traces of red paint exist on Menkaura’s face and black paint on the queen’s wig.

■Figures seem to stride forward, but simultaneously are anchored to the stone behind; it is unusual for the female figure to be striding with the male.

■Figures stare out into space (the afterlife?).

Function

■Receptacle for the ka of the pharaoh and his queen.

■Wife’s simple and affectionate gesture, and/or presenting him to the gods.

Figure 3.7: King Menkaura and queen, Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, 2490–2472 B.C.E., graywacke, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Materials

■Extremely hard stone used; symbolizes the permanence of the pharaoh’s presence and his strength on earth.

Context

■Menkaura’s powerful physique and stride symbolize his kingship, as does his garb: nemes on the head, an artificial beard, and a kilt with a tab.

■Original location was the temple of Menkaura’s pyramid complex at Giza.

■Society’s view of women is expressed in the ankle-length tightly draped gown covering the queen’s body; men and women of the same height indicated equality.

■Society’s view of the king is expressed in his broad shoulders, muscular arms and legs, and firm stomach.

Theory

■Because of the prominence of the female figure, it has been suggested that she is not his wife but his mother, or the goddess Hathor—although the figure has no divine attributes.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 18

Web Source www.mfa.org/collections/object/king-menkaura-mycerinus-and-queen-230

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Royalty

–Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene (Figure 28.7)

–Wall plaque from Oba’s palace (Figure 27.3)

–Augustus of Prima Porta (Figure 6.15)

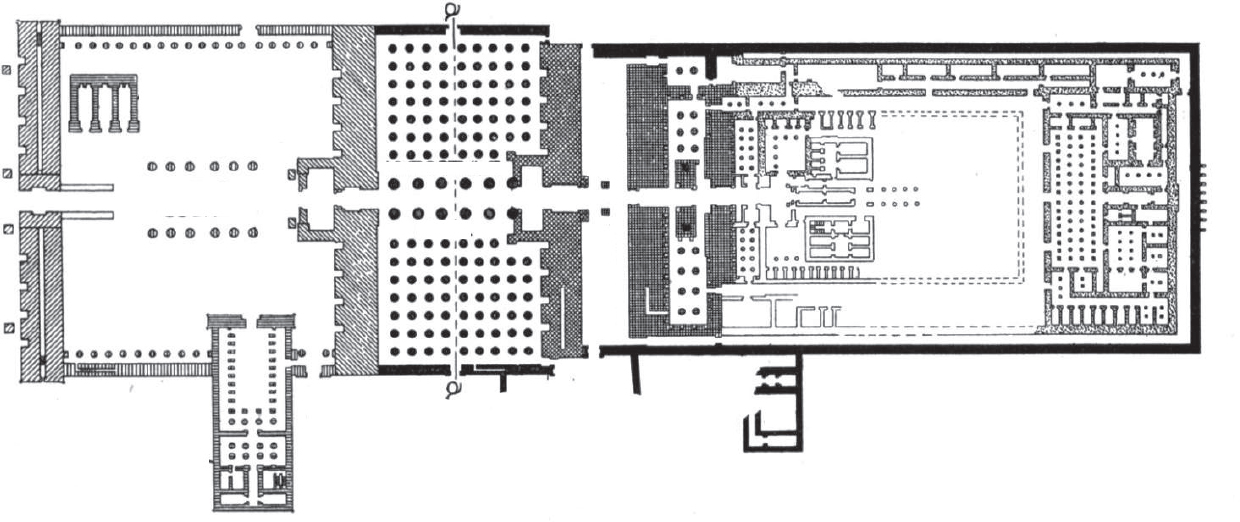

Figure 3.8a: Temple of Amun-Re and Hypostyle Hall, Temple: 1550 B.C.E., Hall: 1250 B.C.E., New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties, cut sandstone and mud brick, Karnak, near Luxor, Egypt

Temple of Amun-Re and Hypostyle Hall, Temple: 1550 B.C.E., Hall: 1250 B.C.E., New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties, cut sandstone and mud brick, Karnak, near Luxor, Egypt (Figures 3.8a, 3.8b, and 3.8c)

Form

■Axial plan.

■Pylon temple.

■Hypostyle halls.

■Massive lintels link the columns together.

■Huge columns, tightly packed together, admit little light into the sanctuary.

■Tallest columns have papyrus capitals; a clerestory allows some light and air into the darkest parts of the temple.

■Columns elaborately painted.

■Columns carved in sunken relief.

■Bottom of columns have bud capitals.

■Massive walls enclose complex.

■Enter complex through massive sloped pylon gateway into a peristyle courtyard, then through a hypostyle hall, and then into the sanctuary, where few were allowed.

Figure 3.8b: Hypostyle Hall, 1250 B.C.E., New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties, cut sandstone and mud brick, Karnak, near Luxor, Egypt

Function

■Egyptian temple for the worship of Amun-Re.

■God housed in the darkest and most secret part of the complex, only accessed by priests and pharaohs.

Figure 3.8c: Plan of Temple of Amun-Re and Hypostyle Hall, Temple: 1550 B.C.E., Hall: 1250 B.C.E., New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties, cut sandstone and mud brick, Karnak, near Luxor, Egypt

Context

■Adjacent is an artificial sacred lake—a symbol of the sacred waters of the world that existed before time.

■Located on the east side of the Nile, linked by a road with the Karnak temple for the Opet festival.

■The complex was built near this lake over time; symbolically, it arose from the waters the way civilization did.

■Theory that the temple represents the beginnings of the world:

–Pylons are the horizon.

–Floor rises to the sanctuary of the god.

–Temple roof is the sky.

–Columns represent plants of the Nile: lotus, papyrus, palm, etc.

History

■Built by succeeding generations of pharaohs over a great expanse of time.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 20

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/87

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Houses of Worship

–Lakshmana Temple (Figures 23.7a, 23.7b, 23.7c, 23.7d)

–Santa Sabina (Figures 7.3a, 7.3b, 7.3c)

–Great Mosque, Isfahan (Figures 9.13a, 9.13b, 9.13c)

Mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, c. 1473–1458 B.C.E., New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, sandstone partly carved into a rock cliff, near Luxor, Egypt (Figure 3.9a)

Form

■Three colonnaded terraces and two ramps.

■Visually coordinated with the natural setting; long horizontals and verticals of the terraces and colonnades repeat the patterns of the cliffs behind; patterns of dark and light in the colonnade are reflected in the cliffs.

■Terraces were originally planted as gardens with exotic trees.

Figure 3.9a: Mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, c. 1473–1458 B.C.E., New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, sandstone partly carved into a rock cliff, near Luxor, Egypt

Function

■Hatshepsut declared that she built the temple as “a garden for my father, Amun” (Hatshepsut claimed to have been of divine birth, sired by the god Amun).

■Was used only for special religious events; lacks subsidiary buildings for storing offerings, the accommodation of priests, temple administration, workshops, and other function-structures.

■For reasons of cultic purity, the royal burial could not be in the temple. The royal tomb was located in the mountain behind the temple and reached by way of the Valley of the Kings.

Context

■First time the achievements of a woman are celebrated in art history; Hatshepsut’s body is interred elsewhere.

■Temple aligned with the winter solstice, when light enters the farthest section of the interior.

■Located on the west side of the Nile across from Thebes.

■Perhaps designed by Senenmut, a high-ranking official in Hatshepsut’s court.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 21

Web Source https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc69.pdf

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Architecture and Setting

–Acropolis, Athens (Figure 4.16a)

–Wright, Fallingwater (Figure 22.16)

–Nan Madol (Figures. 28.1a, 28.1b)

Kneeling statue of Hatshepsut, 1473–1458 B.C.E., red granite, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Figure 3.9b)

Form

■Male pharaonic attributes: nemes or headcloth, false beard, kilt.

■Wears the white crown of Upper Egypt.

■Queen is depicted in male costume of a pharaoh, yet slender proportions and slight breasts indicate femininity.

Function

■Statue of the god brought before sculpture in a procession.

■Processions up the mortuary temple passed in front of this statue of Hatshepsut.

■One of 200 statues placed around the complex.

Context

■One of 10 statues of Hatshepsut with offering jars, part of a ritual in honor of the sun god; pharaoh would kneel only before a god.

■Inscription on base says she is offering plants to Amun, the sun god.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 21

Web Source https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544449

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Guardian Figures

–Nio guardian figure (Figures 25.1c, 25.1d)

–Staff god (Figures 28.5a, 28.5b)

–Lamassu (Figure 2.5)

Figure 3.9b: Kneeling statue of Hatshepsut, 1473–1458 B.C.E., red granite, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and three daughters, New Kingdom (Amarna), 18th Dynasty, 1353–1335 B.C.E., limestone, Egyptian Museum, Berlin (Figure 3.10)

Content

■Akhenaton holds his eldest daughter (left), ready to be kissed.

■Nefertiti holds her daughter (right) with another daughter on her shoulder.

■Intimate family relationships are extremely rare in Egyptian art.

Form

■State religion shift indicated by an evolving style in Egyptian art:

–Smoother, curved surfaces.

–Low-hanging bellies.

–Slack jaws.

–Thin arms.

–Epicene bodies.

–Heavy-lidded eyes.

Figure 3.10: Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and three daughters, New Kingdom (Amarna), 18th Dynasty, 1353–1335 B.C.E., limestone, Egyptian Museum, Berlin

■At the end of the sun’s rays, ankhs (an ankh is the Egyptian symbol of life) point to the king and queen.

Function

■The domestic environment was new in Egyptian art; the panel is for an altar in a home.

Technique

■Sunken relief, which is less likely to be damaged than raised relief.

■Sunken relief creates deeper shadows and can be appreciated in the sunlight.

Context

■Akhenaton abandoned Thebes and created a new capital, originally named Akhenaton and later changed to Amarna; the style of art from this period is called the Amarna Style.

■The state religion was changed by Akhenaton to the worship of Aton, symbolized by the sun-disk with a cobra; he changed his name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaton to reflect his devotion to the one god Aton; this is an early example of monotheism.

■Akhenaton and Nefertiti are having a private relationship with their new god, Aton.

■After Akhenaton’s reign, the Amarna style was slowly replaced by more traditional Egyptian representations.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 22

Web Source http://egyptian-museum-berlin.com/c52.php#n_hausaltar_01.jpg

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Genre Scenes

–Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance (Figure 17.10)

–Courbet, Stone Breakers (Figure 21.1)

–Grave stele of Hegeso (Figure 4.7)

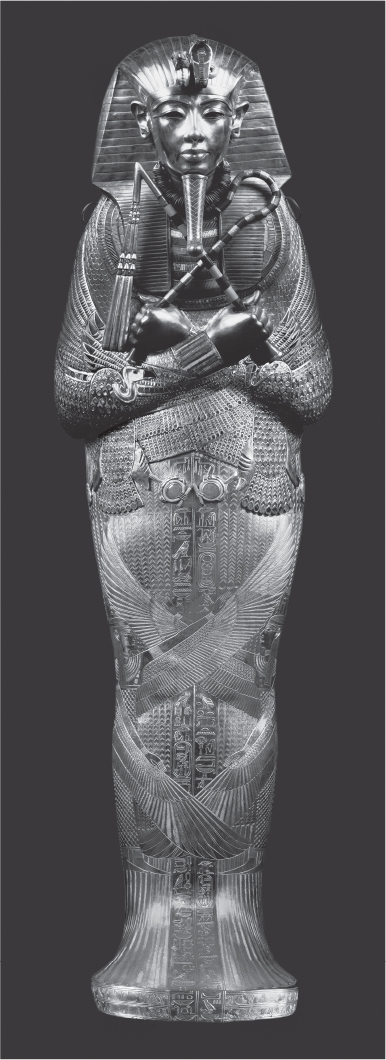

Innermost coffin of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c. 1323 B.C.E., gold with inlay of enamel and semiprecious stones, Egyptian Museum, Cairo (Figure 3.11)

Form

■Gold coffin (6 feet, 7 inches long) containing the body of the pharaoh.

■Smooth, idealized features on the mask of the boy king.

■Holds a crook and a flail, symbols of Osiris.

Function

■Mummified body of King Tutankhamun was buried with 143 objects, on his head, neck, abdomen, and limbs; a gold mask was placed over his head.

Context

■When Akhenaton died, two pharaohs ruled briefly, and then his son Tutankhamun reigned for ten years, from age 9 to 19.

■Tutankhamun’s father and mother were brother and sister; his wife was his half-sister; perhaps he was physically handicapped because of genetic inbreeding.

History

■Famous tomb discovered by Howard Carter in 1922.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 23

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tuta/hd_tuta.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Commemoration

–Sarcophagus of the Spouses (Figure 5.4)

–Moai (Figure 28.11)

–Ndop (Figure 27.5a)

Figure 3.11: Innermost coffin of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c. 1323 B.C.E., gold with inlay of enamel and semiprecious stones, Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Last judgment of Hunefer, from his tomb (Page from the Book of the Dead), New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, c. 1275 B.C.E., painted papyrus scroll, British Museum, London (Figure 3.12)

Form

■Narrative on a uniform register (read right to left).

Function

■Illustration from the Book of the Dead, an Egyptian book of spells and charms that acted as a guide for the deceased to make his or her way to eternal life.

Content

■Top register: Hunefer in white at left before a row of judges.

■Main register: the jackal-headed god of embalming, Anubis, leads the deceased into a hall, where his soul is weighed against a feather. If his sins weigh more than a feather, he will be condemned.

■The hippopotamus/lion figure, Ammit, between the scales, will eat the heart of an evil soul.

■The god Thoth, who has the head of a bird, is the stenographer writing down these events in the hieroglyphics that he invented.

■Osiris, god of the underworld, enthroned on the right, will subject the deceased to a day of judgment.

Context

■Hunefer was a scribe who had priestly functions.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 24

Web Source https://www.bbc.com/news/av/entertainment-arts-11669904/a-rare-view-of-egyptian-book-of-the-dead

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Scrolls

–Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace (Figures 25.3a, 25.3b)

–Bayeux Tapestry (Figures 11.7a, 11.7b)

–Bing, A Book from the Sky (Figures 29.8a, 29.8b)

Figure 3.12: Last judgment of Hunefer, from his tomb (Page from the Book of the Dead), New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, c. 1275 B.C.E., painted papyrus scroll, British Museum, London

VOCABULARY

Amarna style: art created during the reign of Akhenaton, which features a more relaxed figure style than in Old and Middle Kingdom art (Figure 3.10)

Ankh: an Egyptian symbol of life

Axial plan: a building with an elongated ground plan (Figure 3.8c)

Clerestory: a roof that rises above lower roofs and thus has window space beneath

Engaged column: a column that is not freestanding but attached to a wall (Figure 3.2)

Ground line: a baseline upon which figures stand (Figure 3.4a)

Hierarchy of scale: a system of representation that expresses a person’s importance by the size of his or her representation in a work of art (Figure 3.4a)

Hieroglyphics: Egyptian writing using symbols or pictures as characters (Figure 3.12)

Hypostyle: a hall that has a roof supported by a dense thicket of columns (Figure 3.8b)

In situ: a Latin expression that means that something is in its original location

Ka: the soul, or spiritual essence, of a human being that either ascends to heaven or can live in an Egyptian statue of itself

Mastaba: Arabic for “bench,” a low, flat-roofed Egyptian tomb with sides sloping down to the ground (Figure 3.1)

Necropolis: literally, a “city of the dead,” a large burial area (Figure 3.6b)

Papyrus: a tall aquatic plant whose fiber is used as a writing surface in ancient Egypt (Figure 3.12)

Peristyle: a colonnade surrounding a building or enclosing a courtyard (Figure 3.8a)

Pharaoh: a king of ancient Egypt (Figure 3.11)

Pylon: a monumental gateway to an Egyptian temple marked by two flat, sloping walls between which is a smaller entrance (Figure 3.8a)

Register: a horizontal band, often on top of another, that tells a narrative story (Figure 3.4)

Relief sculpture: sculpture which projects from a flat background. A very shallow relief sculpture is called a bas-relief (pronounced: bah-relief) (Figure 3.4) Contrast: Sunken relief

Reserve column: a column that is cut away from rock but has no support function

Sarcophagus (plural, sarcophagi): a stone coffin

Stylized: A schematic, nonrealistic manner of representing the visible world and its contents, abstracted from the way that they appear in nature

Sunken relief: a carving in which the outlines of figures are deeply carved into a surface so that the figures seem to project forward (Figure 3.10)

SUMMARY

Egyptian civilization covers a huge expanse of time that is marked by the building of monumental funerary monuments and expansive temple complexes. The earliest remains of Egyptian civilization show an interest in elaborate funerary practices, which resulted in the building of the great stone pyramids.

Egyptian figural style remained constant throughout much of its history, with its emphasis on broad frontal shoulders and profiled heads, torso, and legs. In the Old Kingdom the figures appear static and imperturbable. In the Amarna period the figures lose their motionless stances and have body types that are softer and increasingly androgynous.

The contents of the tomb of the short-lived King Tutankhamun give the modern world a glimpse into the spectacular richness of Egyptian tombs. One wonders how much more lavish the tomb of Ramses II must have been.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.The purpose of the seated scribe sculpture is to

(A)illustrate the large retinue the pharaoh had

(B)show how the pharaoh was literate and intelligent

(C)indicate how the pharaoh used scribes to write down his deeds

(D)attend to the pharaoh’s needs in the afterlife

Question 2 refers to the following image.

2.The ground plan of this building indicates that

(A)vast spaces are vaulted for large interiors

(B)there are four entrances, one for each cardinal point of the compass

(C)the interior rooms are dominated by closely spaced, thick columns

(D)the outside walls are low and shallow to allow the Nile to ceremonially flood the interior

3.The painting called the Last judgment of Hunefer shows the

(A)eternal punishment proclaimed upon a damned soul

(B)deceased being asked to account for the deeds in his life

(C)might of the pharaoh in deciding life and death

(D)rules of conduct imposed on the lowly and the mighty alike

4.Egyptian sculptors sometimes used sunken relief rather than bas-relief because

(A)sunken reliefs highlight the contours of the surfaces being carved so that the columns appear to have images protruding from their surfaces

(B)sunken reliefs are easier to carve, a necessity because Egyptians used soft bronze-age tools to carve into hard stones like graywacke

(C)sunken reliefs act as supporting elements to sustain the weight of the lintels

(D)sunken reliefs cast deep shadows so that the images can be read more clearly in the Egyptian sun

5.Which historical event is represented on the Palette of King Narmer?

(A)The founding of the first Egyptian dynasty

(B)The conquering of the Assyrians

(C)The abandonment of the polytheistic Egyptian religion in favor of one god, Aton

(D)The unification of Upper and Lower Egypt

Short Essay

Practice Question 6: Continuity and Change

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

This is the inner coffin of King Tutankhamun from c. 1323 B.C.E.

Where in Egypt was this coffin found?

Explain the contextual reasons this site was chosen for the burial of this coffin.

How does this site differ from the context of ancient Egyptian Old Kingdom burials?

Using at least two specific details, discuss how this work is part of a tradition of pharaonic burial.

ANSWER KEY

1.D

2.C

3.B

4.D

5.D

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(D) Images of scribes were placed in tombs to attend to the pharaoh’s needs in the afterlife. Whereas all of the other choices indicate how pharaohs used scribes, this sculpture of a seated scribe had the specific purpose of being placed in a tomb so that the ka could be accommodated, if necessary.

2.(C) There are thick round circles in a grid pattern on the ground plan which represent columns placed very closely together.

3.(B) This painting is a Last Judgment scene, in which the deceased’s soul is weighed against a feather to see if he is pure enough to face the gods.

4.(D) Sunken relief sculpture is no easier or more difficult to carve than any other sculpture no matter what tools are being used or what materials are being carved. Sunken reliefs do not enhance a structural function, nor do they protrude from the surface. However, in the severe Egyptian summer months, sunken reliefs cast shadows that more dramatically highlight the features of the relief sculpture.

5.(D) The Palette of King Narmer symbolically represents a conflation of all the episodes leading to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Where in Egypt was this coffin found? |

1 |

The coffin was found in a tomb in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. |

Explain the contextual reasons this site was chosen for the burial of this coffin. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■This was the traditional burial ground for Egyptian kings. ■The valley was naturally protected by cliffs against grave robbers. ■The cliffs and tombs could be easily dug from the rock here. |

How does this site differ from the context of ancient Egyptian Old Kingdom burials? |

1 |

Answers could include: ■It is a tomb rather than a pyramid. ■The coffin was buried in a tomb in a vast valley, as opposed to a pyramid field. ■The coffin was buried in a small suite of rooms underground rather than in a chamber in the center of a pyramid. |

Using at least two specific details, discuss how this work is part of a tradition of pharaonic burial. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■Elaborate funerary ceremonies; 143 objects found with the body. ■Gold symbolizes eternity; used extensively throughout the tomb. ■Holds a crook and a flail, symbols of Osiris. ■Above the head are symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt: the cobra and the falcon. ■Idealization of facial features of the king. |