Content Area: Ancient Mediterranean, 3500 B.C.E.–300 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: 3500 B.C.E.–641 C.E.

| Sumerian Art | c. 3500–2340 B.C.E. | Iraq |

| Babylonian Art | 1792–1750 B.C.E. | Iraq |

| Assyrian Art | 883–612 B.C.E. | Iraq |

| Persian Art | c. 559–331 B.C.E. | Iran |

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Statues of votive figures from Tell Asmar)

Essential Knowledge:

■Ancient Near Eastern art takes place mostly in the city-states of Mesopotamia.

■Religion plays a dominant role in the art of the Ancient Near East.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: White Temple on its ziggurat)

Essential Knowledge:

■Figures are constructed within stylistic conventions of the time, including hierarchy of scale, registers, and stylized human forms.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Persepolis)

Essential Knowledge:

■There are many similarities among artistic styles in the Ancient Near East, which indicates a vibrant exchange of ideas.

■Ancient Near Eastern artistic conventions influenced later periods in art history.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Code of Hammurabi)

Essential Knowledge:

■Ancient Near Eastern art concentrates on royal figures and gods.

■Ancient Near Eastern architecture is characterized by ziggurats and palaces that express the power of the gods and rulers.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Standard of Ur)

Essential Knowledge:

■The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written record.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Ancient Near East is where almost everything began first: writing, cities, organized religion, organized government, laws, agriculture, bronze casting, even the wheel. It is hard to think of any other civilization that gave the world as much as the ancient Mesopotamians.

Large populations emerged in the fertile river valleys that lie between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. City centers boomed as urbanization began to take hold. Each group of people vied to control the central valleys, taking turns occupying the land and eventually relinquishing it to others. This layering of civilizations has made for a rich archaeological repository of successive cultures whose entire history has yet to be uncovered.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Kings sensed from the beginning that artists could help glorify their careers. Artists could aggrandize images, bring the gods to life, and sculpt narrative tales that would outlast a king’s lifetime. They could also write in cuneiform and imprint royal names on everything from cylinder seals to grand relief sculptures. This was the start of one of the most symbiotic relationships in art history between patron and artist.

ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN ART

One of the most fundamental differences between the prehistoric world and the civilizations of the Ancient Near East is the latter’s need to urbanize; buildings were constructed to live, govern, and worship in. However, in the Near East, stone was at a premium and wood was scarce but earth was in abundant supply. The first great buildings of the ancient world, ziggurats, were made of baked mud, and they were tall, solid structures that dominated the flat landscape. Although mud needed care to protect it from erosion, it was a cheap material that could be resupplied easily.

Human beings did not play a central role in prehistoric art. Lascaux has precisely one male figure but more than six hundred cave paintings of animals. A few human figures like the anthromorphic stele populated a sculptural world full of animals and spirals. However, in the Near East artists were more likely to depict clothed humans with anatomical precision. Near Eastern figures are actively engaged in doing something: hunting, praying, performing a ritual.

One of the characteristics of civilizations that settle down rather than nomadically wander is the size of the sculpture they produce. Nomadic people cannot carry large objects on their migrations, but cities retain monumental objects as a sign of their permanence. Near Eastern sculptures could be very large—the lamassus, man-headed winged bulls, at Persepolis are gigantic. The interiors of palaces were filled with large-scale relief sculptures gently carved into stone surfaces.

The invention of writing enabled people to permanently record business transactions in a wedge-shaped script called cuneiform. Laws were written down, taxes were accounted for and collected, and the first written epic, Gilgamesh, was copied onto a series of tablets. Stories needed to be illustrated, making narrative painting a necessity. Walls of ancient palaces not only had sculptures of rulers and gods but also had narratives of their exploits.

Near Eastern art begins a popular ancient tradition of representing animals with human characteristics and emotions; some Sumerian animals have human heads. The personification of animals was continued by the Egyptians (the Sphinx) and the Greeks (the Minotaur), sometimes producing fantastical creations. There was also a trend to combine animal parts, as in the Lamassu (c. 700 B.C.E.) (Figure 2.5), with the human head at the top of a hoofed winged animal.

SUMERIAN ART

Sumerian art, as contrasted with prehistoric art, has realistic-looking figures acting out identifiable narratives. Figures are cut from stone, with negative space hollowed out under their arms and between their legs. Eyes are always wide open; men are bare-chested and wear a kilt. Women have their left shoulder covered; their right is exposed. Nudity is a sign of debasement; only slaves and prisoners are nude. Sculptures were placed on stands to hold them upright. There was a free intermixing of animal and human forms, so it is common to see human heads on animal bodies, and vice versa. Humans are virtually emotionless.

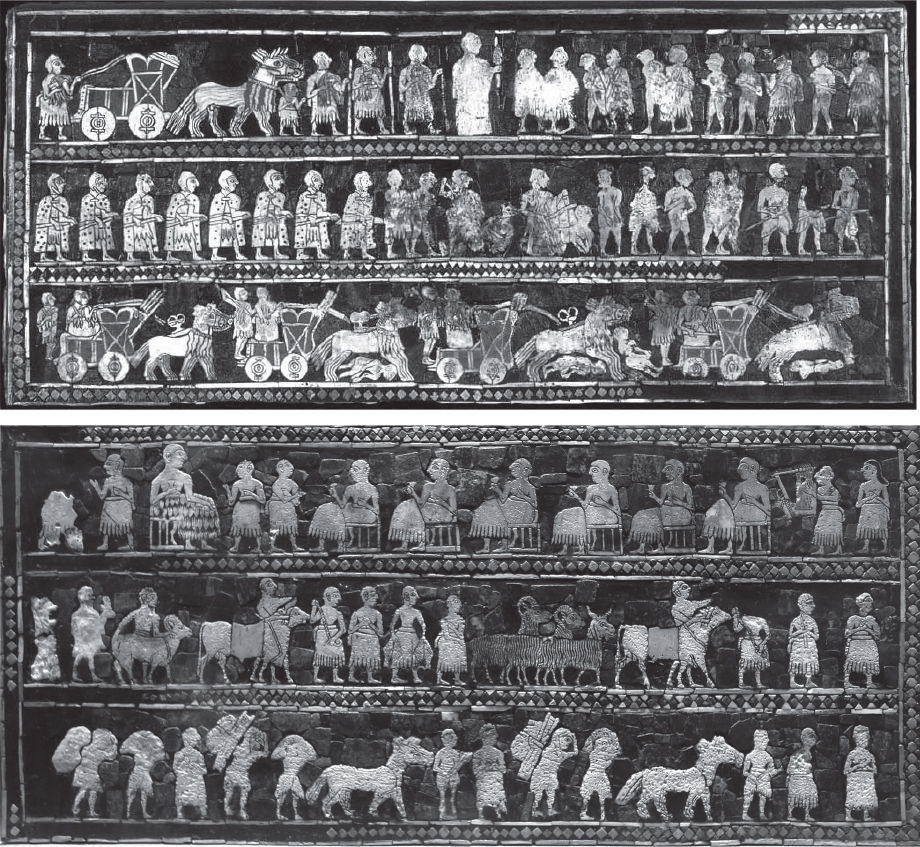

Important figures are the largest and most centrally placed in a given composition. Such an arrangement is called hierarchy of scale and can be seen in the Standard of Ur (c. 2600 B.C.E.) (Figures 2.3a, 2.3b), in which the king is the tallest figure, located in the middle of the top register.

In the Sumerian world the gods symbolized powers that were manifest in nature. The local god was an advocate for a given city in the assembly of gods. Thus, it was incumbent upon the city to preserve the god and his representative, the king, as well as possible. The temple, therefore, became the center point of both civic and religious pride.

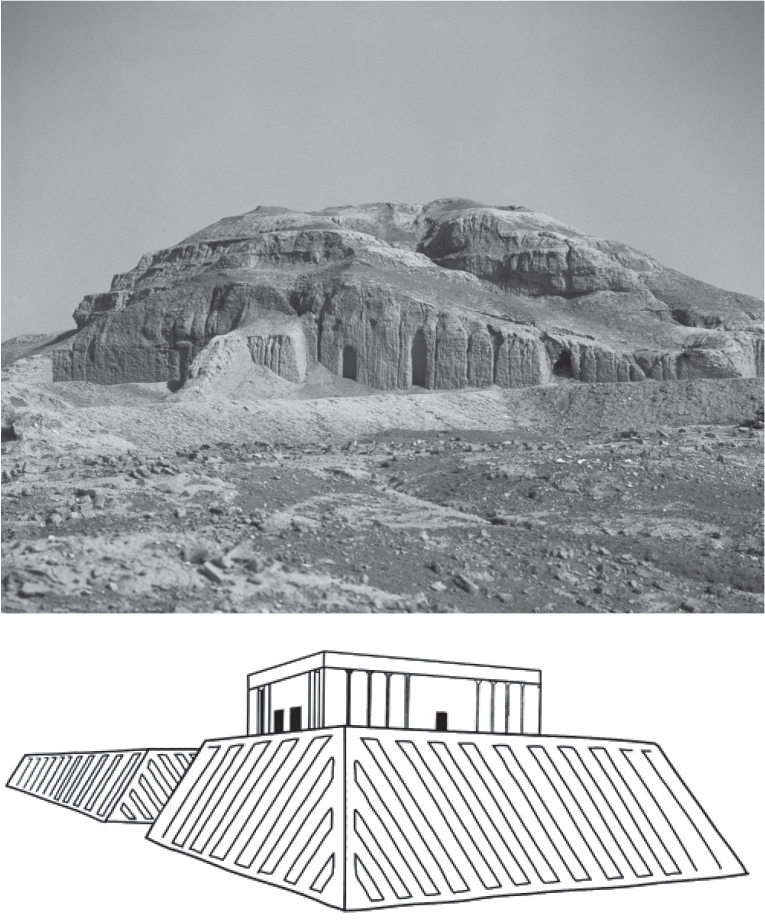

Figures 2.1a and 2.1b: White Temple and its ziggurat with reconstruction, c. 3500–3000 B.C.E., mud brick, Uruk (modern Warka), Iraq

White Temple and its ziggurat, c. 3500–3000 B.C.E., mud brick, Uruk (modern Warka), Iraq (Figures 2.1a and 2.b)

Form

■Buttresses spaced across the surface to create a contrasting light-and-shadow pattern.

■The ziggurat tapers downward so that rainwater washes off.

■Entire form resembles a mountain, creating a contrast between the vast flat terrain and the man-made mountain.

■Bent-axis plan: ascending the stairs requires angular changes of direction to reach the temple (compare Mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, Figure 3.9a)

Function

■On top of the ziggurat is a terrace for outdoor rituals and a temple for indoor rituals.

■The temple on the top was small, set back, and removed from the populace; access reserved for royalty and clergy; only the base of the temple remains.

■The temple interior contained a cella and smaller rooms meant for the deities to assemble before a select group of priests.

Materials

■Mud-brick building built on a colossal scale and covered with glazed tiles or cones.

■Whitewash used to disguise the mud appearance; hence the modern name of White Temple.

Context

■Large settlement at Uruk of 40,000, based on agriculture and specialized labor.

■Uruk may be the first true city in history; the first with monumental architecture.

■Ziggurat sited within the city.

■Deity was Anu, the god of the sky, the most important Sumerian deity.

■Gods descend from the heavens to a high place on Earth; hence the Sumerians built ziggurats as high places.

■Four corners oriented to the compass; cosmic orientation.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 12

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Religious Centers on Man-Made or Natural Hilltops

–Yaxchilán Structure 40 (Figure 26.2a)

–Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlán (Figure 26.5a)

–Acropolis (Figure 4.16a)

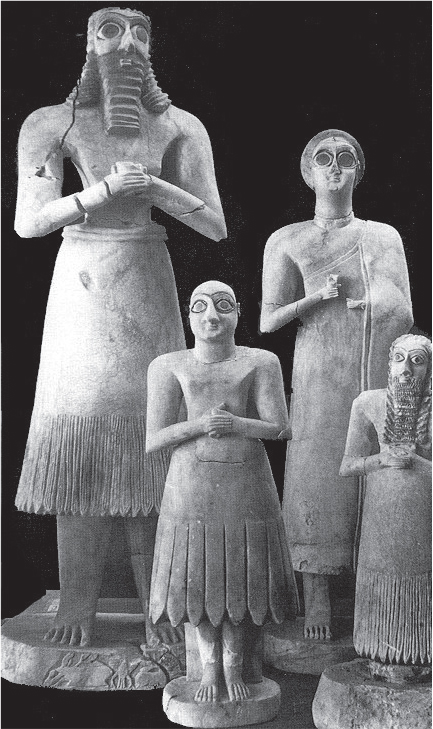

Statues of votive figures, from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), c. 2700 B.C.E., gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, Iraq Museum, Baghdad, and the University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (Figure 2.2)

Form

■Figures are of different heights, denoting hierarchy of scale.

■Hands are folded in a gesture of prayer.

■Huge eyes in awe, spellbound, perhaps staring at the deity.

■Men: bare chested; wearing belt and skirt; beard flows in ripple pattern.

■Women: dress draped over one shoulder.

■Arms and feet cut away.

■Pinkie in a spiral; chin a wedge shape; ear a double volute.

Function

■Some have inscriptions on back: “It offers prayers.” Other inscriptions tell the names of the donors or gods.

■Figures represent mortals; placed in a temple to pray before a sculpture of a god.

Context

■Gods and humans physically present in their statues.

■None have been found in situ, but buried in groups under the temple floor.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 14

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/TOAH/hd/edys/hd_edys.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Shrine Figures

–Female deity from Nukuoro (Figure 28.2)

–Veranda post (Figure 27.14)

–Ikenga (shrine figure) (Figure 27.10)

Figure 2.2: Statues of votive figures, from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), c. 2700 B.C.E., gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, Iraq Museum, Baghdad and the University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

Standard of Ur from the Royal Tombs at Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar, Iraq), c. 2600–2400 B.C.E., wood inlaid with shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone, British Museum, London (Figures 2.3a and 2.3b)

Form

■Figures have broad frontal shoulders; bodies in profile; twisted perspective.

■Emphasis on eyes, eyebrows, ears.

■Organized in registers; figures stand on ground lines.

■Reads from bottom to top.

Content

■Two sides: war side and peace side; may have been two halves of a narrative; early example of a historical narrative.

■War side: Sumerian king, half a head taller than the others, has descended from his chariot to inspect captives brought before him, some of whom are debased by their nakedness; in lowest register, chariots advance over the dead.

■Peace side: food brought in a procession to the banquet; musician plays a lyre; ruler is the largest figure—he wears a kilt made of tufts of wool; may have been a victory celebration after a battle.

Figures 2.3a and 2.3b: War (top) and Peace (bottom) from the Standard of Ur from the Royal Tombs at Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar, Iraq), c. 2600–2400 B.C.E., wood inlaid with shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone, British Museum, London

Context

■Found in tomb at the royal cemetery at Ur in modern Iraq.

■Reflects extensive trading network: lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, shells from the Persian Gulf, and red limestone from India.

Theories

■Perhaps used as part of soundbox for a musical instrument; modern name of “standard” comes from the theory that it was once placed on a pole and carried in a procession (few now accept this).

■The two scenes may illustrate the dual nature of an ideal Sumerian ruler: the victorious general and the father of his people, who promotes general welfare.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 16

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Narrative in Art

–Bayeux Tapestry (Figures 11.7a, 11.7b)

–Column of Trajan (Figure 6.16)

–Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace (Figures 25.3a, 25.3b)

BABYLONIAN ART

Because of the survival of the famous Code of Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 B.C.E.) (Figure 2.4), Babylon comes down to us as a seemingly well-ordered state with a set of strict laws handed down from the god Shamash himself. Nothing was spared in the decoration of the capital, Babylon, covered with its legendary hanging gardens and walls of glazed tile.

Code of Hammurabi, Babylon (modern Iran), Susian, c. 1792–1750 B.C.E., basalt, Louvre, Paris (Figures 2.4a and 2.4b)

Form

■A stele meant to be placed in an important location.

Function

■Below the main scene contains one of the earliest law codes ever written; symbolically shows a ruler’s need to establish civic harmony in a civilized world.

■300 law entries placed below the images, symbolically showing the god Shamash handing the laws to Hammurabi.

Content

■Sun god, Shamash (patron of justice), enthroned on a ziggurat, hands Hammurabi a rope, a ring, and a rod of kingship.

■Shamash is in a frontal view and a profile at the same time; headdress is in profile; rays (wings?) appear from behind his shoulders.

■Shamash’s beard is fuller than Hammurabi’s, illustrating Shamash’s greater wisdom.

■Shamash, judge of the sky and the earth, with a tiara of four rows of horns, presents signs of royal power, the scepter and the ring, to Hammurabi.

■They stare at one another directly even though their shoulders are frontal; composite views.

■Hammurabi depicted with a speaking/greeting gesture.

Context

■Written in cuneiform.

■Text in Akkadian language, read right to left and top to bottom in 51 columns.

■Law articles are written in a formula: “If a person has done this, then that will happen to him.”

History

■Hammurabi (1792–1750 B.C.E.) united Mesopotamia in his lifetime.

■Took Babylon from a small power to a dominant kingdom; after his death the empire dwindled.

Figures 2.4a and 2.4b: Code of Hammurabi, Babylon (modern Iran), Susian, c. 1792–1750 B.C.E., basalt, Louvre, Paris

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 19

Web Source http://musee.louvre.fr/oal/code/indexEN.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Humans and the Divine

–Jayavarman VII as Buddha (Figure 23.8d)

–Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings (Figure 23.9)

–Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (Figures 17.4a, 17.4b)

ASSYRIAN ART

Assyrian artists praised the greatness of their king, his ability to kill his enemies, his valor at hunting, and his masculinity. Figures are stoic, even while hunting lions or defeating an enemy. Animals, however, possess considerable emotion. Lions are in anguish and cry out for help. This domination over a mighty wild beast expressed the authority of the king over his people and the powerful forces of nature.

Cuneiform appears everywhere in Assyrian art; it is common to see words written across a scene, even over the bodies of figures. Shallow relief sculpture is an Assyrian specialty, although the lamassus are virtually three-dimensional as they project noticeably from the walls they are attached to.

Lamassu, from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad, Iraq), c. 720–705 B.C.E., alabaster, Louvre, Paris (Figure 2.5)

Form

■Human-headed animal guardian figures: face of a person, ears and body of a bull.

■Winged.

■Appears to have five legs: when seen from the front, it seems to be standing at attention; when seen from the side, the animal seems to be walking.

■Faces exude calm, serenity, and harmony.

Figure 2.5: Lamassu, from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad, Iraq), c. 720–705 B.C.E., alabaster, Louvre, Paris

Materials

■Carved from a single piece of stone.

■Meant to hold up the walls and arch of a gate.

■Stone is rare in Mesopotamian art and contrasts greatly with the mud-brick construction of the palace.

Function

■Meant to ward off enemies both visible and invisible.

■Inscriptions in cuneiform at the bottom portion of the lamassu declare the power of the king and curse his enemies.

Context

■Sargon II founded a capital at Khorsabad; the city was surrounded by a wall with seven gates.

■The protective spirits (guardians) were placed at either side of each gate.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 25

Web Source http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/winged-human-headed-bull

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Hybrid Figures

–Sphinx (Figure 3.6a)

–Buk (mask) (Figure 28.9)

–Mutu, Preying Mantra (Figure 29.25)

PERSIAN ART

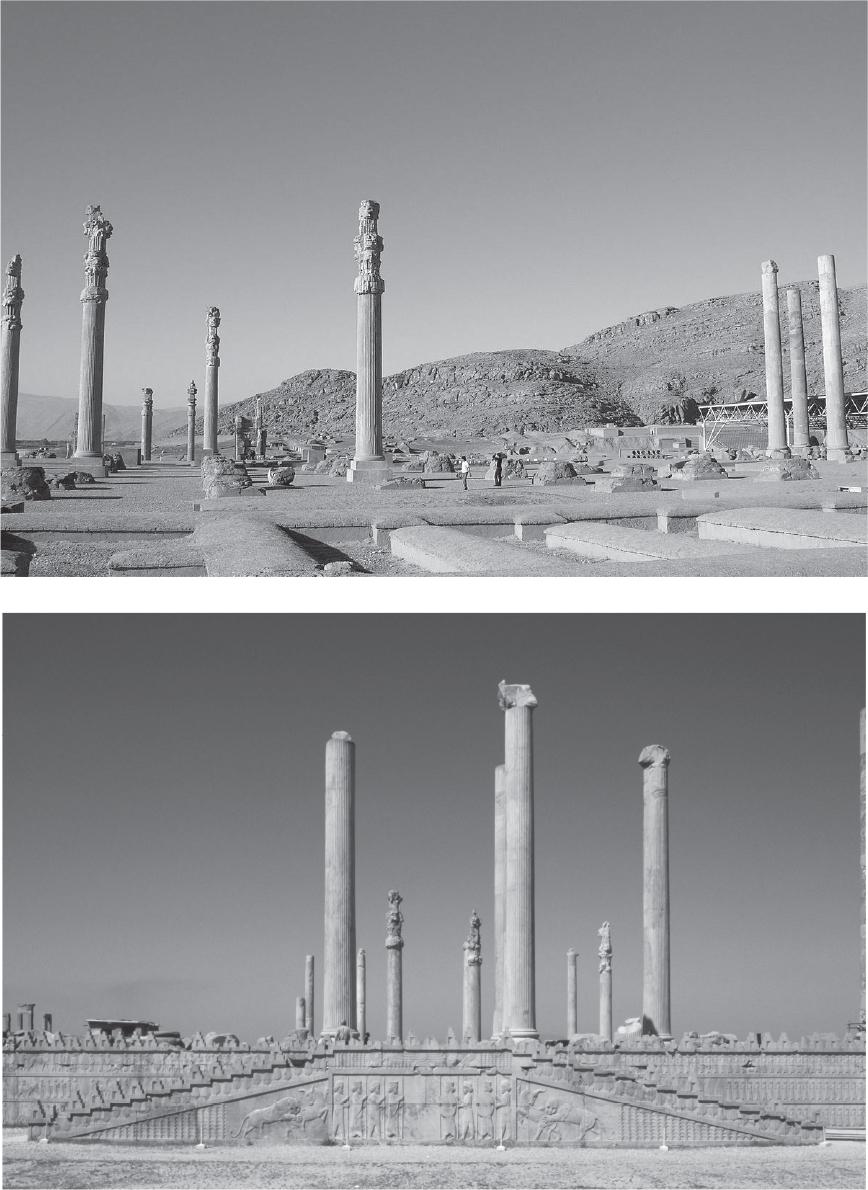

Persia was the largest empire the world had seen up to this time. As the first great empire in history, it needed an appropriate capital as a grand stage to impress people at home and dignitaries from abroad. The Persians erected monumental architecture, huge audience halls, and massive subsidiary buildings for grand ceremonies that glorified their country and their rulers (Figures 2.6a and 2.6b). Persian architecture is characterized by columns topped by two bull-shaped capitals holding up a wooden roof.

Audience Hall (apadana) of Darius and Xerxes, c. 520–465 B.C.E., limestone, Persepolis, Iran (Figures 2.6a and 2.6b)

Form

■Built on artificial terraces, as is most Mesopotamian architecture.

■Columns have a bell-shaped base that is an inverted lotus blossom; the capitals are bulls or lions.

■Everything seems to have been built to dwarf the viewer.

Function

■Built not so much as a complex of palaces, but rather as a seat for spectacular receptions and festivals.

■One enters the complex through gigantic gates depicting lamassu figures. Above the gates is an inscription, the Gates of All Nations, which proudly announces this complex as the seat of a great empire.

■Audience hall (apadana) had 36 columns covered by a wooden roof; held thousands of people; was used for the king’s receptions; had stairways adorned with reliefs of the New Year’s festival and a procession of representatives of 23 subject nations.

■Hypostyle hall, derived from Egypt, is an indication of one of the many cultures that inspired the complex.

Figures 2.6a and 2.6b: above: Audience Hall (apadana) of Darius and Xerxes; below: apadana stairway, c. 520–465 B.C.E., limestone, Persepolis, Iran

Materials

■Mud brick with stone facing; stone symbolizing durability and strength.

Context and Interpretation

■Relief sculptures depict delegations from all parts of the empire bringing gifts to be stored in the local treasury; Darius selected this central location in Persia to ensure protection of the treasury.

■Carved onto the stairs are the immortals, the king’s guard, who were so called because they always numbered 10,000; originally painted and adorned with metal accessories; some covered in gold leaf.

■Stairs have a central relief of the king enthroned with attendants, the crown prince behind him, and dignitaries bowing before him.

■Orderly and harmonious world symbolized by static processions.

History

■Built by Darius I and Xerxes I; destroyed by Alexander the Great, perhaps as an act of revenge for the destruction of the Acropolis in Athens (Figure 4.16a).

■Many cultural influences (Greeks, Egyptians, Babylonians) contributed to the building of the site, as a sign of Persian cosmopolitan imperial culture.

Content Area Ancient Mediterranean, Image 30

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/114/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ceremonial Spaces

–Forum of Trajan (Figure 6.10a)

–Forbidden City (Figure 24.2a)

–Great Zimbabwe (Figures 27.1a, 27.1b)

VOCABULARY

Apadana: an audience hall in a Persian palace (Figure 2.6a)

Apotropaic: having the power to ward off evil or bad luck

Bent-axis: an architectural plan in which an approach to a building requires an angular change of direction, as opposed to a direct and straight entry (Figure 2.1)

Capital: the top element of a column

Cella: the main room of a temple where the god is housed

Cuneiform: a system of writing in which the strokes are formed in a wedge or arrowhead shape

Façade: the front of a building. Sometimes, more poetically, a speaker can refer to a “side façade” or a “rear façade”

Ground line: a baseline upon which figures stand (Figures 2.3a, 2.3b)

Ground plan: the map of a floor of a building

Hierarchy of scale: a system of representation that expresses a person’s importance by the size of his or her representation in a work of art (Figure 2.2)

Lamassu: a colossal winged human-headed bull in Assyrian art (Figure 2.5)

Lapis lazuli: a deep-blue stone prized for its color

Negative space: empty space around an object or a person, such as the cut-out areas between a figure’s legs or arms of a sculpture

Register: a horizontal band, often on top of another, that tells a narrative story (Figures 2.3a, 2.3b)

Relief sculpture: sculpture that projects from a flat background. A very shallow relief sculpture is called a bas-relief (pronounced: bah-relief) (Figures 2.4a, 2.4b)

Stele (plural: stelae): a stone slab used to mark a grave or a site (Figures 2.4a, 2.4b)

Votive: offered in fulfillment of a vow or a pledge (Figure 2.2)

Ziggurat: a pyramid-like building made of several stories that indent as the building gets taller; thus, ziggurats have terraces at each level (Figure 2.1)

SUMMARY

The Ancient Near East saw the birth of world civilizations, symbolized by the first works of art that were used in the service of religion and the state. Rulers were quick to see that their image could be permanently emblazoned on stelae that celebrated their achievements for posterity to admire. The invention of writing created a systematic historical and artistic record of human achievement.

Common characteristics of Ancient Near Eastern art include the union of human and animal elements in a single figure, the use of hierarchy of scale, and the deification of rulers.

Because the Mesopotamian river valleys were poor in stone, most buildings in this region were made of mud brick and were either painted or faced with tile or stone. Entranceways to cities and palaces were important; fantastic animals acted as guardian figures to protect the occupants and ward off the evil intentions of outsiders.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.The Standard of Ur, an ancient Sumerian work, shows that at an early date there was extensive trading between peoples as illustrated by the use of

(A)lapis lazuli from Afghanistan

(B)bronze from India

(C)papyrus from Egypt

(D)marble from Greece

Questions 2–4 refer to the images below.

2.The White Temple is constructed on a large platform base that raises it above the ground and gives the structure considerable height. This technique was highly influential for hundreds of years and can be seen in

(A)the Great Stupa from Sanchi, India

(B)the Great Pyramids of Giza, Egypt

(C)the Palace of Darius, at Persepolis, Iran

(D)Stonehenge in Wiltshire, United Kingdom

3.The White Temple and its ziggurat symbolize

(A)that the gods required their buildings to be of mud brick to represent the impermanence of life

(B)the belief that a bent-axis plan limits the number of worshippers on the site

(C)that the gods live in relative seclusion at the top of a ziggurat, approachable by a select few

(D)the power of the Persian state to build a massive temple

4.The White Temple and its ziggurat has the following design element:

(A)It has tapered sides for the purpose of washing off rainwater.

(B)It was guarded by composite sculptures called lamassus.

(C)It has a columned hall, called an apadana, used for ceremonies.

(D)It has a small interior chamber that held the tomb of the king.

5.The laws expressed on the Code of Hammurabi can be summarized as

(A)forgiveness is the highest form of justice

(B)the only way to deter crime is to use the death penalty

(C)justice depends on your ability to pay

(D)the punishment reflects the crime

Short Essay

Practice Question 3: Visual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

This is the Code of Hammurabi from c. 1792–1750 B.C.E.

Describe the subject matter of the Code of Hammurabi.

Describe at least two visual characteristics of the Code of Hammurabi.

Using specific contextual evidence, explain how the Code of Hammurabi was intended to function.

Using specific visual evidence, explain how the subject matter or visual characteristics of the Code of Hammurabi reinforce its function.

ANSWER KEY

1.A

2.C

3.C

4.A

5.D

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(A) The work has no marble, papyrus, or bronze in it. Lapis lazuli, a rich blue stone, was imported from Afghanistan.

2.(C) The Palace of Darius is also raised on a high platform to give it a more formidable presence.

3.(C) Ziggurat temples were accessible to only a few important figures in Sumerian society. The ziggurat is not built of impermanent materials because it represents the passing of life; it was built of mud brick because that was the only building material available to the Sumerians. A bent-axis plan does not limit the number of participants; it was used for ceremonial purposes.

4.(A) There is no indication that there were any burials associated with the White Temple or its ziggurat; nor did it have guardian figures or columned halls. The sides were pitched so that rainwater would not collect on the mud brick and erode the structure.

5.(D) The laws on the Hammurabi code can be summarized as the severity of the punishment reflects the magnitude of the crime. What you have done will be done unto you.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Describe the subject matter of the Code of Hammurabi. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Below the main scene contains one of the earliest law codes ever written; symbolically shows a ruler’s need to establish civic harmony in a civilized world. ■300 law entries placed below the grouping, symbolically given from the god Shamash to Hammurabi. |

Describe at least two visual characteristics of the Code of Hammurabi. |

1 point each |

Answers could include: ■Sun god, Shamash, enthroned on a ziggurat, hands Hammurabi a rope, a ring, and a rod of kingship. ■Shamash is in frontal view and profile at the same time; headdress is in profile; rays (wings?) from behind his shoulder. ■They stare at one another directly even though their shoulders are frontal; composite views. ■Hammurabi depicted with a speaking/greeting gesture. |

Using specific contextual evidence, explain how the Code of Hammurabi was intended to function. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■A stele meant to be placed in an important location. ■The stele spells out the laws of the land in a clear and orderly fashion. ■The stele represents the power of the king to organize human behavior. ■The stele represents Shamash’s will as expressed through Hammurabi. |

Using specific visual evidence, explain how the subject matter or visual characteristics of the Code of Hammurabi reinforce its function. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Shamash’s beard is fuller than Hammurabi’s, illustrating Shamash’s greater wisdom. ■Shamash, judge of the sky and the earth, with a tiara of four rows of horns, presents signs of royal power, the scepter and the ring, to Hammurabi. ■By placing the god and the king in the same space, it indicates a direct relationship between the two, and reinforces the legitimacy of the laws inscribed in the code. |