Content Area: Indigenous Americas, 1000 B.C.E.–1980 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: 3500 B.C.E.–1492 C.E. AND BEYOND

Some of the main periods are these:

| Civilization | Date | Location |

| Chavín | 900–200 B.C.E. | Coastal Peru |

| Mayan | 300–900 C.E. and later | Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Yucatán |

| Ancient Puebloans | 550–1400 C.E. | Southwestern United States |

| Mississippian | 800–1500 C.E. | Eastern United States |

| Aztec | 1400–1521 C.E. | Central Mexico, centered in Mexico City |

| Inka | 1438–1532 C.E. | Peru |

| North American Indian | 18th century to present | North America |

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Machu Picchu)

Essential Knowledge:

■The art of the indigenous people of America is among the oldest artistic traditions in the world. It extends from about 10,000 B.C.E. through the time of the European invasions.

■The art of this area can be divided into many cultural and historical groupings both in North and South America.

■Ancient Mesoamerican art (from parts of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize) is characterized by architectural structures such as pyramids, a strong influence of astronomy and calendars on ritual objects, and great value placed on green objects such as jade or feathers.

■Three major cultures of ancient Mesoamerica include the Olmec, the Maya, and the Mexica (also called the Aztecs).

■There is a great emphasis on figural art in ancient Mesoamerica, including representations of rulers and mythical events.

■Art of the central Andes (from Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador) shows a deep respect for animals and plants, as well as shamanistic religions.

■The physical environment of the central Andes (the Amazon, the Andes mountains, and the coastal deserts) plays a large role in art making.

■Art in central Andes was generally made by groups in workshops, rather than by individuals.

■Themes in Andean art particularly address the earth-bound and the celestial.

■Native North American art has diverse themes, but many of the artworks concern nature, animals, and large rituals. Respect for elders is a key unifying factor.

■There is no unifying name for the native people of North America, other than terms that have been imposed by others (i.e., Native Americans, First Nations, etc.)

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Bandolier bag)

Essential Knowledge:

■Mesoamerican civilizations have had a broad impact on the world as a whole.

■Mesoamerican objects were valued and treasured in Europe by connoisseurs and collectors. National museums were opened to promote an understanding of ancient American art. Twentieth-century artists both in Latin America and elsewhere around the world have been influenced by the art of ancient America.

■Current Native Americans today strongly identify with the cultural achievements of their ancestors. Art forms are maintained and revived.

■There are exchanges of materials, ideas, and subject matter between Native Americans and Europeans.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Chavín nose ornament)

Essential Knowledge:

■The modern concept of art is different than the intended purpose of objects from this period. Objects were created to represent or contain a life force, and viewing was seen as a participatory activity.

■Art was generally generated in workshops.

■Rulers were the major patrons. Patrons could also include a family member, a tribal leader, or an elder.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Transformation mask)

Essential Knowledge:

■Mesoamericans and Native Americans use trade materials, animal-based products, and precious stones. Works of art are generally functional.

■Central Andean artists prized featherwork, textiles, and green stones, and favored works made of metal and bone. Ceramics and wood were considered as occupying the lowest end of the artistic scale.

■Pyramids began as earthworks and then grew to multilevel structures. Sites were often added to over many years. Most architecture is made of stone, using the post-and-lintel system and faced with painted sculpture. There are large plazas placed before the pyramids.

■North American Indians produced works which included ceramics, hide paintings, basketry, weaving, adobe structures, and monumental earthworks.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Great Serpent Mound)

Essential Knowledge:

■There are many differences in the cultures of the Americas and therefore many approaches to studying the various art forms.

■Examination of artwork from this period relies on many sources including archaeology and written accounts by colonists.

■A multi disciplinary approach is used to examine the works of this period.

■There are many approaches to Native North American art including archaeology, tribal history, and anthropology.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Humans are not native to the “New World”; Americans do not have an ancestry dating back millions of years, the way they do in Africa or Asia. People migrated from Asia to America over a span of perhaps 30,000 years, crossing the Bering Strait when the frozen winters made the way walkable. Eventually people understood that the climate was good enough to raise crops, particularly in what is today Mexico and Central America, and the population boomed.

As in other parts of the world, local rivalries and jealousies have played their part in the ebb and flow of American civilizations. Some civilizations are intensely cultivated and technological, refining metal ore and developing a firm understanding of astronomy and literature. Others remained nomadic and limited their activities as hunter–gatherers. In any case, when the European colonizers arrived at the end of the fifteenth century, they encountered in some ways a very sophisticated society, but in others, one that did not even possess a functioning wheel and refined metals mostly for jewelry rather than for use.

Each succeeding civilization buried or destroyed the remains of the civilization before, so only the hardiest ruins have survived the test of time. Most of what can be gleaned about pre-Columbian American society is ascertained by archaeologists working on elaborate burial grounds or digging through the ruins of once-great ancient cities.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Artists were commoners, as was true in most societies in the ancient world. Because of their special abilities, however, artists were employed by the state to work at important sites instead of doing menial labor. Some were even members of the royalty. Artists were trained in an apprenticeship program, and reached fame through the rendering of beautifully crafted items.

Ancient Americans used an extremely wide variety of materials in their artwork, usually capitalizing on what was locally available. Since they did not have draught animals, and since wheeled carts were unknown, artists were reliant on what was locally produced, or on objects small enough to trade and carry. Even so, Aztecs, for example, carved in obsidian, jade, copper, gold, turquoise, basalt, sandstone, granite, rock crystal, wood, limestone, and amethyst, among many other media.

Tropical cultures profited from the skins of animals and feathers of birds and produced great works using brilliant plumage. Featherwork became a distinguished art form in the hands of pre-Columbian artists.

CHAVÍN ART

Chavín is a civilization named after its main archaeological site, preserved in coastal Peru. Chavín art is dominated by figural compositions, often shown in a combination of human and animal motifs. Many figures unite various animal forms into one being: fanged mouths are merged with serpents in the hair, for example. Figures are generally heavily rendered with an eye to monumentality. Symmetry is desired; works are carved in low relief on polished surfaces that use rectangular formats.

Chavín architects chose sites that were dramatic, sometimes on mountain tops. Often buildings, such as those at Chavín de Huántar, were built around a U-shaped plan that embraced a plaza and faced out toward an expansive view. Stepped platforms rise to support ceremonial buildings. Some sites are oriented to the cardinal points on the compass, but at Chavín the site seems to be coordinated with an adjacent river, which some say was a reference to water sources and their importance to society.

Chavín de Huántar, 900–200 B.C.E., stone, Northern Highlands, Peru

Function

■A religious capital.

■Temple, 60 meters tall, was adorned with a jaguar sculpture, a symbol of power.

■Hidden entrance to the temple led to stone corridors.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 153

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/330

Plan and Lanzón Stone, granite (Figures 26.1a and 26.1b)

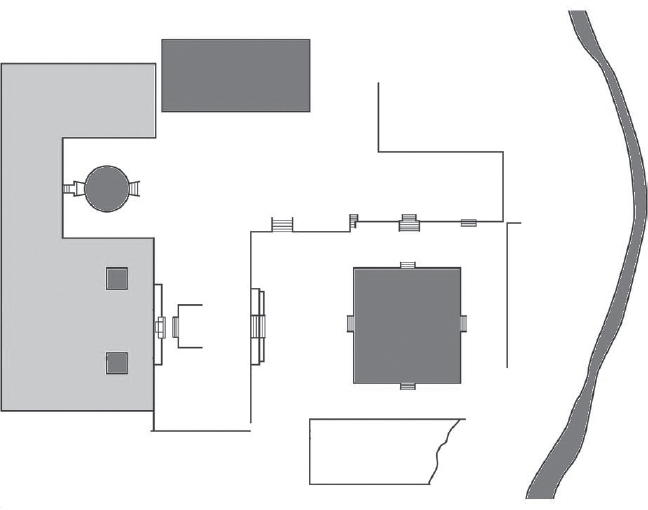

Figure 26.1a: Plan of Chavín de Huántar, 900–200 B.C.E., stone, Northern Highlands, Peru

Figure 26.1b: Lanzón Stone, 900–200 B.C.E., granite, Peru

Form

■Inside the old temple of Chavín is a mazelike system of hallways.

■Passageways have no natural light source; they are lit by candles and lamps.

■At the center, underground, is the Lanzón (Spanish for “blade”) Stone; blade shaped; may also represent a primitive plough; hence, the role of the god in ensuring a successful crop.

■Depicts a powerful figure that is part human (body) and part animal (claws, fangs); the god of the temple complex.

■Head of snakes and a face of a jaguar.

■Eyebrows terminate in snakes.

■Flat relief; designs in a curvilinear pattern.

■15 feet tall.

Function

■Served as a cult figure.

■Center of pilgrimage; however, few had access to the Lanzón Stone.

■Modern scholars hypothesize that the stone acted as an oracle; hence a point of pilgrimage.

■New studies show the importance of acoustics in the underground chamber.

Relief sculpture, granite, Chavín de Huántar (Figure 26.1c)

Figure 26.1c: Relief sculpture, granite, 900–200 B.C.E., Peru

■Shows jaguars in shallow relief.

■Located on the ruins of a stairway at Chavín.

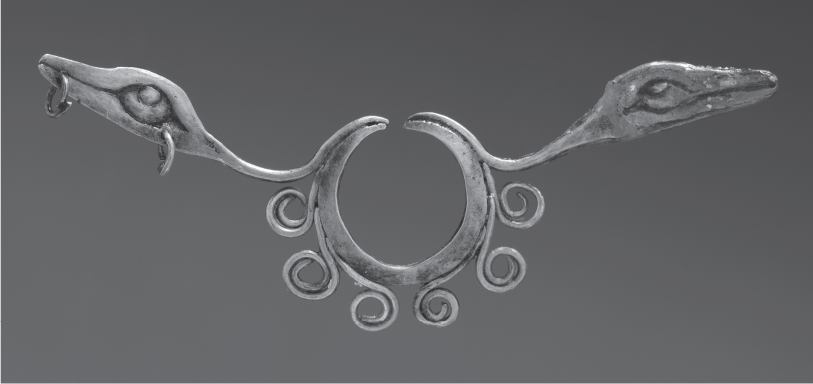

Nose ornament, hammered gold alloy, Cleveland Museum of Art (Figure 26.1d)

Figure 26.1d: Nose ornament, hammered gold alloy, Cleveland Museum of Art

Form

■Worn by males and females under the nose.

■Held in place by the semicircular section at the top.

■Two snake heads on either end.

■Cf. Lanzón Stone (Figure 26.1b): serpent motif appears in both.

Function

■Transforms the wearer into a supernatural being during ceremonies.

Context

■Elite men and women wore the ornaments as emblems of their ties to the religion and eventually were buried with them.

■The Chavín religion is related to the appearance of the first large-scale precious metal objects; revolutionary new metallurgical process.

■Technical innovations express the “wholly other” nature of the religion.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 153

Web Source http://www.clevelandart.org/art/1958.183

MAYAN ART

Mayan sculpture is easy to recognize, because of the unusual Mayan concept of ideal beauty. The model seems to have been a figure with an arching brow, with the indentation above the nose filled in as a continuous bridge between forehead and nose. Most well-to-do Mayans put their children in head braces to create this symbol of beauty if the child was not born with it. Facial types are long and narrow, with full lips and mouths ready to speak. It is common to see figures elaborately dressed with costumes composed of feathers, jade, and jaguar skin. The Mayans preferred narrative art done in relief sculpture. Their relief work has crisp outlines with little attention given to modeling.

Mayan sculpture is typically related to architectural monuments: Lintels, facades, jambs, and so on. Figures of gods are stylized and placed in conventional hieratic poses possessing symbols of beauty, most notably tattooing and crossed eyes. Most Mayan sculptures were painted.

A typical work that appears everywhere in Mayan cities is the chacmool, a figure that is half-sitting and half-lying on his back. The unusual pose of the figure is balanced by the face which turns 90 degrees from the body. Elbows firmly rest on the ground, lending a sloping sense to the body. On his stomach is a plate, which has made some scholars deduce that the figure was meant to receive offerings. Sculptures such as these influenced modern artists such as Henry Moore.

Mayan pyramids are set in wide plazas as a center of civic focus. Grandly proportioned temples accompany pyramids, although their interiors are narrow and tall, giving a certain claustrophobic effect enhanced by the use of corbelled vaulting. Temples had long roof combs on the roof to accentuate their verticality.

Yaxchilán, 725 C.E., limestone, Chiapas, Mexico (Figures 26.2a, 26.2b, and 26.2c)

Figure 26.2a: Structure 40, Yaxchilán, Mayan, 725 C.E., limestone, Chiapas, Mexico

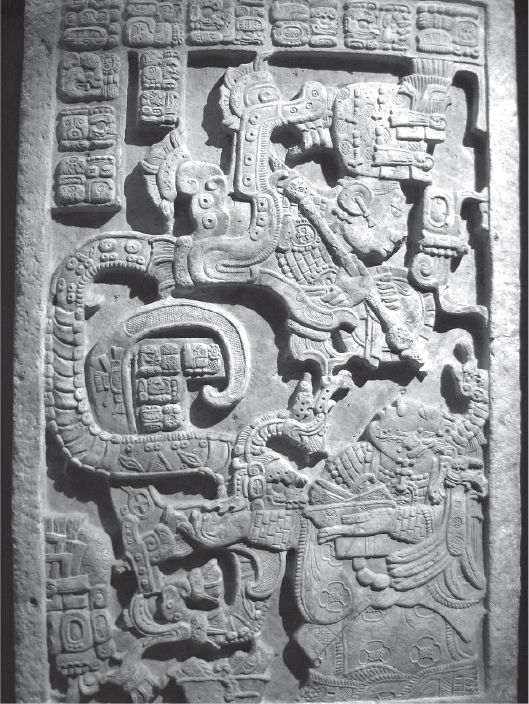

Figure 26.2b: Lintel 25, Structure 23, Yaxchilán, 725 C.E., limestone, British Museum, London

Function

■City set on a high terrace; plaza surrounded by important buildings.

■Flourished c. 300–800 C.E.

Structure 40, Yaxchilán, Mayan, 725 C.E., limestone, Chiapas, Mexico (Figure 26.2a)

Form

■Overlooks the main plaza.

■Three doors lead to a central room decorated with stucco.

■Roof remains nearly intact, with a large roof comb (ornamented stone tops on roofs).

■Corbel arch interior.

Patronage

■Built by ruler Bird Jaguar IV for his son, who dedicated it to him.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 155

Lintel 25, Structure 23, Yaxchilán, 725 C.E., limestone, British Museum, London (Figure 26.2b)

Form and Content

■The lintel was originally set above the central doorway of Structure 23 as a part of a series of three lintels.

■Lady Xook (bottom right) invokes the Vision Serpent to commemorate her husband’s rise to the throne.

■The Vision Serpent has two heads: one has a warrior emerging from its mouth, and the other has Tlaloc, a war god.

■She holds a bowl with bloodletting ceremonial items: stinging spine and bloodstained paper; she runs a rope with thorns through her tongue.

■She burns paper on a dish as a gift to the netherworld.

■The depicted ritual was conducted to commemorate the accession of Shield Jaguar II to the throne.

Function

■Lintels intended to relay a message of the refoundation of the site—there was a long pause in the building’s history.

■Shield Jaguar’s building program throughout the city may have been an attempt to reinforce his lineage and his right to rule.

Context

■The building is dedicated to Lady Xook, Shield Jaguar II’s wife.

■The inscription is written as a mirror image—extremely unusual among Mayan glyphs; uncertain meaning, perhaps indicating she had a vision from the other side of existence and she was acting as an intercessor or shaman.

■The inscription names the protagonist as Shield Jaguar II.

■Bloodletting is central to the Mayan life. When a member of the royal family sheds his or her blood, a portal to the netherworld is opened and gods and spirits enter the world.

Theory

■Some scholars suggest that the serpent on this lintel and elsewhere depicts an ancestral spirit or founder of the kingdom.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 155

Structure 33, Yaxchilán, Mayan, 725 C.E., limestone, Chiapas, Mexico (Figure 26.2c)

Figure 26.2c: Structure 33, Yaxchilán, Mayan, 725 C.E., limestone, Chiapas, Mexico

■Restored temple structure.

■Remains of roof comb with perforations.

■Three central doorways lead to a large single room.

■Corbel arch interior.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 155

Web Source https://www.peabody.harvard.edu/cmhi/site.php?site=Yaxchilan

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Temples

–White Temple and its ziggurat (Figures 2.1a, 2.1b)

–Lakshmana Temple (Figures 23.7a, 23.7b)

–Todai-ji (Figure 25.1a)

ANCIENT PUEBLOANS

Anasazi is a term that means “ancient ones” or “ancient enemies” in the Navajo language. This is the name that used to be used to indicate the culture of ancient puebloans. They are most famous for their meticulously rendered pueblos, which are composed of local materials. A core of rubble and mortar is usually faced with a veneer of polished stone. The thickness of the base walls were used to determine the size of the overall superstructure, with some pueblos daring to raise themselves five or six stories tall. All pueblos faced a well-defined plaza that was the religious and social center of the complex.

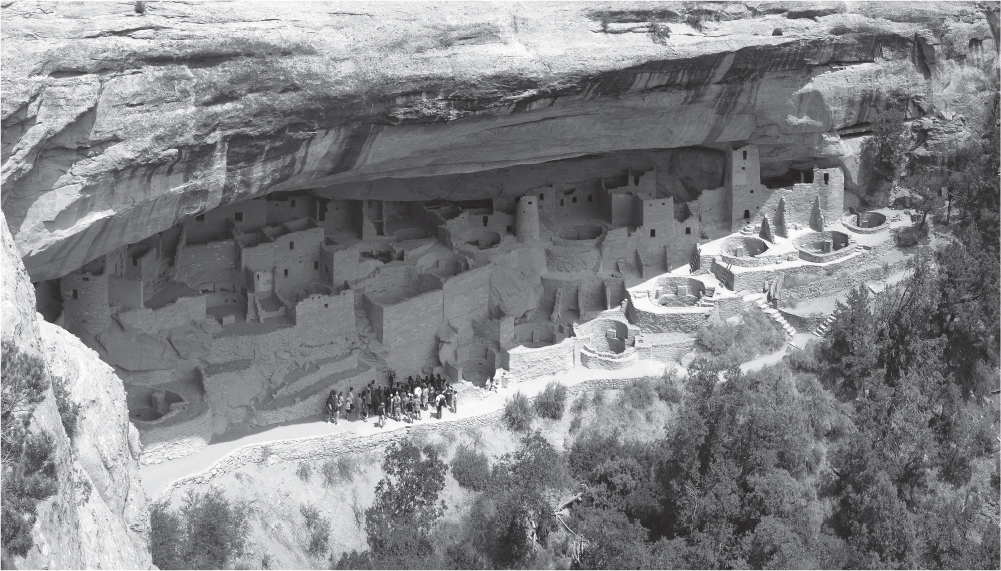

Mesa Verde cliff dwellings, Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi), 450–1300 C.E., sandstone, Montezuma County, Colorado (Figure 26.3)

Figure 26.3 Mesa Verde cliff dwellings, Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi), 450–1300 C.E., sandstone, Montezuma County, Colorado

Form

■The top ledge houses supplies in a storage area; cool and dry area out of the way; accessible only by ladder.

■Each family received one room in the dwelling.

■Plaza placed in front of the abode structure; kivas face the plaza.

Function

■The pueblo was built into the sides of a cliff, housed about one hundred people.

■Clans moved together for mutual support and defense.

Context

■Farming done on the plateau above the pueblo; everything had to be imported into the structure; water seeped through the sandstone and collected in trenches near the rear of the structure.

■Low winter sun penetrated the pueblo; high summer sun did not enter the interior and therefore it stayed relatively cool.

■Inhabited for two hundred years; probably abandoned when the water source dried up.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 154

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/27

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Cliffside

–Bamiyan Buddhas (Figures 23.2a, 23.2b)

–Longmen Caves (Figures 24.9a, 24.9b)

–Petra (Figure 6.9b)

MISSISSIPPIAN ART

An increase in agriculture meant a population boom, as sustained communities evolved in fertile areas. Eastern Native Americans were mound-builders and created an impressive series of earthworks that survive in great numbers even today. Huge mound complexes, such as Cahokia, Illinois, were impressive city-states that governed wide areas. Other mounds, such as Great Serpent Mound (Figure 26.4), were built in effigy shapes of uncertain meaning. Many of these mounds have baffled archaeologists, because they clearly could only be fully appreciated from the air or a high vantage point, which mound builders did not possess.

Figure 26.4: Great Serpent Mound, Mississippian (Eastern Woodlands), c. 1070 C.E., earthwork/effigy mound, Adams County, southern Ohio

Great Serpent Mound, Mississippian (Eastern Woodlands), c. 1070 C.E., earthwork/effigy mound, Adams County, southern Ohio (Figure 26.4)

Context

■Many mounds were enlarged and changed over the years, not built in one campaign.

■Effigy mounds popular in Mississippian culture.

■Associated with snakes and crop fertility.

■There are no burials associated with this mound, though there are burial sites nearby.

Theories

■Influenced by comets? Astrological phenomenon? Head pointed to summer solstice sunset?

■Theory that it could be a representation of Halley’s Comet in 1066.

■Rattlesnake as a symbol in Mississippian iconography; could this play a role in interpreting this mound?

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 156

Web Source http://worldheritageohio.org/serpent-mound/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Earthworks

–Smithson, Spiral Jetty (Figure 22.26)

AZTEC ART

Aztec art is most famously represented by gold jewelry that survives in some abundance, and jade and turquoise carvings of great virtuosity. The aggressive nature of Aztec religions, with its centering on violent ceremonies of blood-letting, was often manifest in great stone sculptures of horrifying deities such as Coyolxauhqui, whose characteristics include human remains from bloody sacrifices.

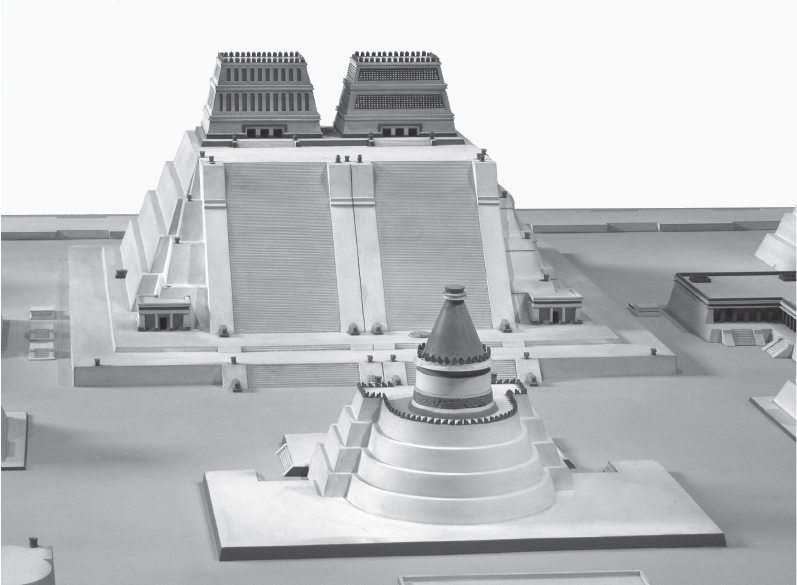

Templo Mayor (Main Temple), Mexica (Aztec), 1375–1520, stone, Tenochtitlán, Mexico City, Mexico (Figure 26.5a)

Figure 26.5a: Templo Mayor (Main Temple), Mexica (Aztec), 1375–1520, stone, Tenochtitlán, Mexico City, Mexico

Form

■Pyramids built one atop the other so that the final form encases all previous pyramids; seven building campaigns.

■Pyramids have a step-like series of setbacks; not the smooth-surfaced pyramids seen in Egypt.

■Characterized by four huge flights of very vertical steps leading to temples placed on top.

Function

■Tenochtitlán was laid out on a grid; city seen as the center of the world.

■The temple structures on top of each pyramid were dedicated to and housed the images of the two important deities.

Context

■Two temples atop a pyramid, each with a separate staircase:

–North: dedicated to Tlaloc, god of rain, agriculture.

–South: dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, god of sun and war.

–At the spring and autumn equinoxes, the sun rises between the two.

–Large braziers put on top where the sacred fires burned.

–Temple structures housed images of the deities.

■Temples begun in 1375; rebuilt six times; destroyed by the Spanish in 1520.

■The destruction of this temple and reuse of its stones by the Spanish asserted a political and spiritual dominance over the conquered civilization.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 157

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/teno_2/hd_teno_2.htm

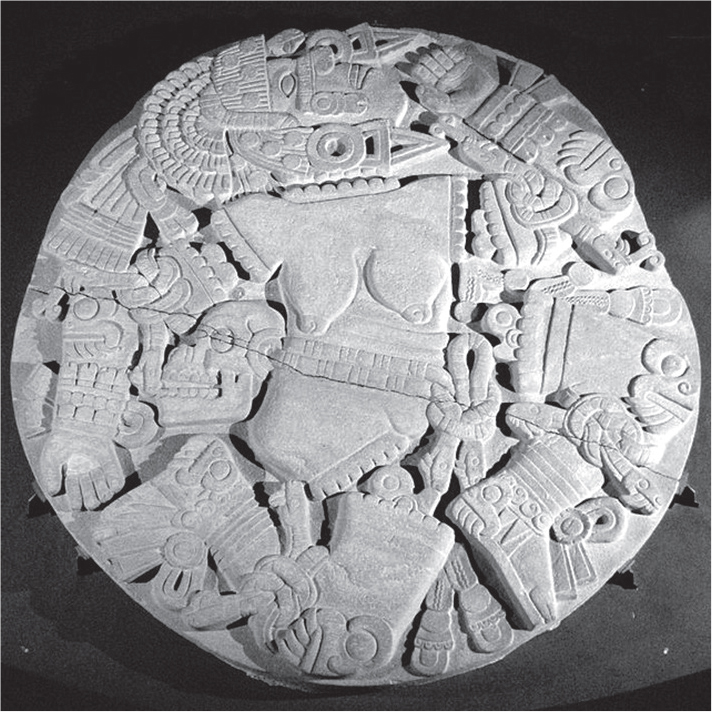

Coyolxauhqui “She of the Golden Bells,” 1469 (?), volcanic stone, Museum of the Templo Mayor, Mexico City (Figure 26.5b)

Figure 26.5b: Coyolxauhqui Stone, volcanic stone

Form

■Circular relief sculpture.

■Once brilliantly painted.

■So called because of the bells she wears as earrings.

Context

■Coyolxauhqui and her many brothers plotted the death of her mother, Coatlicue, who became pregnant after tucking a ball of feathers down her bosom. When Coyolxauhqui chopped off Coatlicue’s head, a child, Huitzilopochtli, popped out of the severed body fully grown and dismembered Coyolxauhqui, who fell dead at the base of the shrine.

■This stone represents the dismembered moon goddess, Coyolxauhqui, who is placed at the base of the twin pyramids of Tenochtitlán.

■Aztecs sacrificed people and then threw their dismembered remains down the steps of the temple as Huitzilopochtli did to Coyolxauhqui.

■Aztecs similarly dismembered enemies and threw them down the stairs of the great pyramid to land on the sculpture of Coyolxauhqui.

■A relationship was established between the death and decapitation of Coyolxauhqui with the sacrifice of enemies at the top of Aztec pyramids.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 157

Web Source http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/aztec/interactive/index.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Human Figure in Relief

–Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and three daughters (Figure 3.10)

–Victory adjusting her sandal (Figure 4.6)

–Anthropomorphic stele (Figure 1.2)

Calendar Stone, basalt (Figure 26.5c)

Figure 26.5c: Calendar Stone, basalt

Context

■Aztecs felt they needed to feed the sun god human hearts and blood.

■A tongue in the center of the stone coming from the god’s mouth is a representation of a sacrificial flint knife used to slash open the victims.

■Circular shape reflects the cyclic nature of time.

■Two calendar systems, separate but intertwined.

■Calendars synced every fifty-two years in a time of danger, when the Aztecs felt a human sacrifice could ensure survival.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 157

Web Source http://www.kidsdiscover.com/quick-reads/understanding-mysterious-aztec-sun-stone/

Olmec-style mask, jadeite (Figure 26.5d)

Figure 26.5d: Olmec-style mask, jadeite

■Found on the site; actually a much older work executed by the Olmecs.

■Olmec works have a characteristic frown on the face; pugnacious visage; baby face; a cleft in the center of the head carved from greenstone.

■Shows that the Aztecs collected and embraced artwork from other cultures, including early Mexican cultures such as the Olmec and Teotihuacán.

■Shows that the Aztecs had a wide-ranging merchant network that traded historical items.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 157

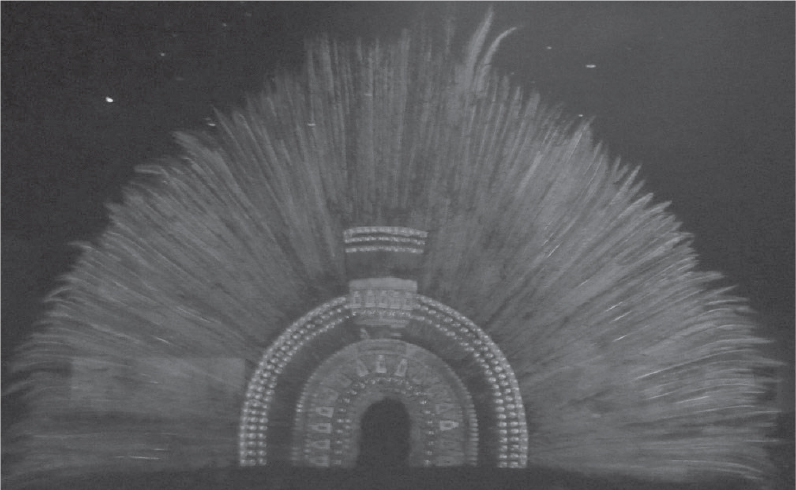

Ruler’s feather headdress (probably of Motecuhzoma II), Mexica (Aztec), 1428–1520, feathers (quetzal and blue cotinga) and gold, Museum of Ethnology, Vienna (Figure 26.6)

Figure 26.6: Ruler’s feather headdress (probably of Motecuhzoma II), Mexica (Aztec), 1428–1520, feathers (quetzal and cotinga) and gold, Museum of Ethnology, Vienna

Form

■Made from 400 long green feathers, the tails of the sacred quetzal birds; male birds produce only two such feathers each.

■The number 400 symbolizes eternity.

Function

■Ceremonial headdress of a ruler.

■Part of an elaborate costume.

Context

■Only known Aztec feather headdress in the world.

■Feathers indicate trading across the Aztec Empire.

■Headdress possibly part of a collection of artifacts given by Motechuzoma (Montezuma) to Cortez for Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire.

■Current dispute over ownership of the headdress; today it is housed in the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna, Austria.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 158

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Exotic Materials

–‘Ahu ‘ula (Figure 28.4)

–Circle of the González family, Screen with the Siege of Belgrade and hunting scene (Figures 18.3a, 18.3b)

–González, Virgin de Guadalupe (Figure 18.4)

INKAN ART

Inkan architecture defies the odds by building impressive and well-designed cities in some of the most inaccessible or inhospitable places on earth. Typically Inkan builders used ashlar masonry of perfectly grooved and fitted stones placed together in almost a jigsaw puzzle arrangement. All stones have slightly beveled edges that emphasize the joints. The buildings tend to taper upward like a trapezoid, the favorite building shape of early Americans.

The impressive Inka Empire stretched from Chile to Colombia and was well-maintained by an organized system of roads that united the country in an efficient communication network. The Inka had no written language, so much of what we know about the civilization has been deduced from archaeological remains.

Maize cobs, c. 1440–1533, sheet metal/repoussé, metal alloys, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Figure 26.7)

Figure 26.7: Maize cobs, c. 1440–1533, sheet metal/repoussé, metal alloys Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Technique and Form

■Repoussé technique.

■Hollow metal object.

■Life-size.

Function

■May have been part of a garden in which full-sized metal sculptures of maize plants and other items were put in place alongside actual plants in the Qorinkancha garden.

■May have been used to ensure a successful harvest.

Context

■Maize was the principal food source in the Andes.

■Maize was celebrated by having sculptures fashioned out of sheet metal.

■Black maize was common in Peru; oxidized silver reflects that.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 160

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Metalwork

–Merovingian looped fibulae (Figure 10.1)

–Golden Stool (Figure 27.4)

–Muhammad ibn al-Zain, Baptistère de Saint Louis (Figure 9.6)

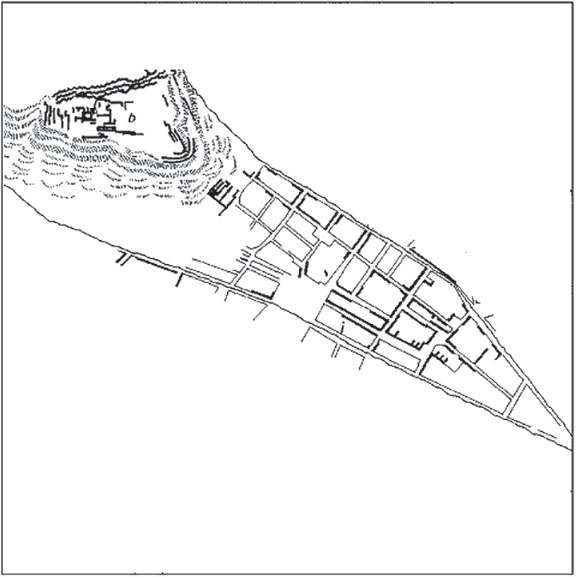

City of Cusco plan, Peru, c. 1440 (Figure 26.8a)

Figure 26.8a: Plan of the City of Cusco, c. 1440

Form

■In the shape of the puma, a royal animal.

■Modern plaza is in the place where the puma’s belly would be.

■Head, a fortress; heart, a central square.

Function

■Historic capital of the Inka Empire.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 159

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/273

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: City Planning

–Athenian Agora (Figure 4.15)

–Forum of Trajan (Figure 6.10a)

–Forbidden City (Figures 24.2a, 24.2b, 24.2c, 24.2d)

Qorikancha: main temple, church, and convent of Santo Domingo, c. 1440, convent added 1550–1650, andesite, Cusco, Peru (Figure 26.8b)

Figure 26.8b: Qorikancha: main temple, church, and convent of Santo Domingo, c. 1440, convent added 1550–1650, andesite, Cusco, Peru

Form

■Ashlar masonry; carefully grooved and beveled edges of the stone fit together in a puzzle-like formation.

■Slight spacing among stones allows movement during earthquakes.

■Walls taper upward; examples of Inkan trapezoidal architecture.

■Temple displays Inkan use of interlocking stonework of great precision.

■Original exterior walls of the temple were decorated in gold to symbolize sunshine.

■Spanish chroniclers insist that the walls and floors of the temple were covered in gold.

Function

■Qorikancha: golden enclosure; once was the most important temple in the Inkan world.

■Once was an observatory for priests to chart the skies.

Context

■The location is important; placed at the convergence of the four main highways and connected to the four districts of the empire; the temple cemented the symbolic importance of religion, uniting the divergent cultural practices that were observed in the vast territory controlled by the Inkas.

■Remains of the Inkan Temple of the Sun form the base of the Santo Domingo convent built on top.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 159

Web Source https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/mar/25/cusco-coricancha-temple-history-cities-50-buildings

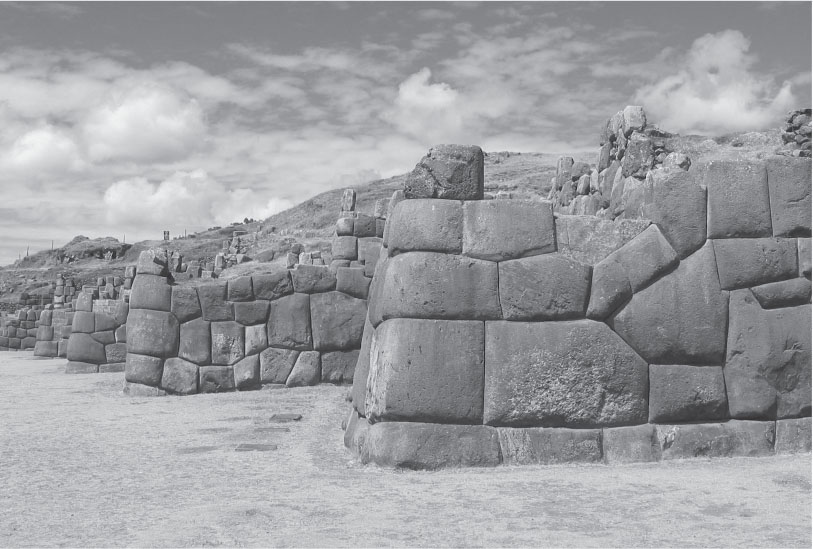

Walls at Saqsa Waman (Sacsayhuaman), c. 1440, sandstone, Peru (Figure 26.8c)

Figure 26.8c: Walls at Saqsa Waman (Sacsayhuaman), c. 1440, sandstone, Peru

Form

■Ashlar masonry.

■Ramparts contain stones weighing up to seventy tons, brought from a quarry two miles away.

Context

■Complex outside the city of Cusco, Peru, at the head of the puma-shaped plan of the city.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 159

Machu Picchu, Inka, 1450–1540, granite, Central Highlands, Peru (Figure 26.9a)

Figure 26.9a: City of Machu Picchu, Inka, 1450–1540, granite, Central Highlands, Peru

Form

■Buildings built of stone with perfectly carved rock rendered in precise shapes and grooved together; thatched roofs.

■Outward faces of the stones were smoothed and grooved.

■Two hundred buildings, mostly houses; some temples, palaces, and baths, and even an astronomical observatory; most in a basic trapezoidal shape.

■Entryways and windows are trapezoidal.

■People farmed on terraces.

Function

■Originally functioned as a royal retreat.

■The estate of fifteenth-century Inkan rulers.

■So remote that it was probably not used for administrative purposes in the Inkan world.

■Peaceful center: many bones were uncovered, but none of them indicate war-like behavior.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 161

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/274

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Public spaces

–Acropolis (Figure 4.16a)

–Persepolis (Figure 2.6a, 2.6b)

–Mesa Verde (Figure 26.3)

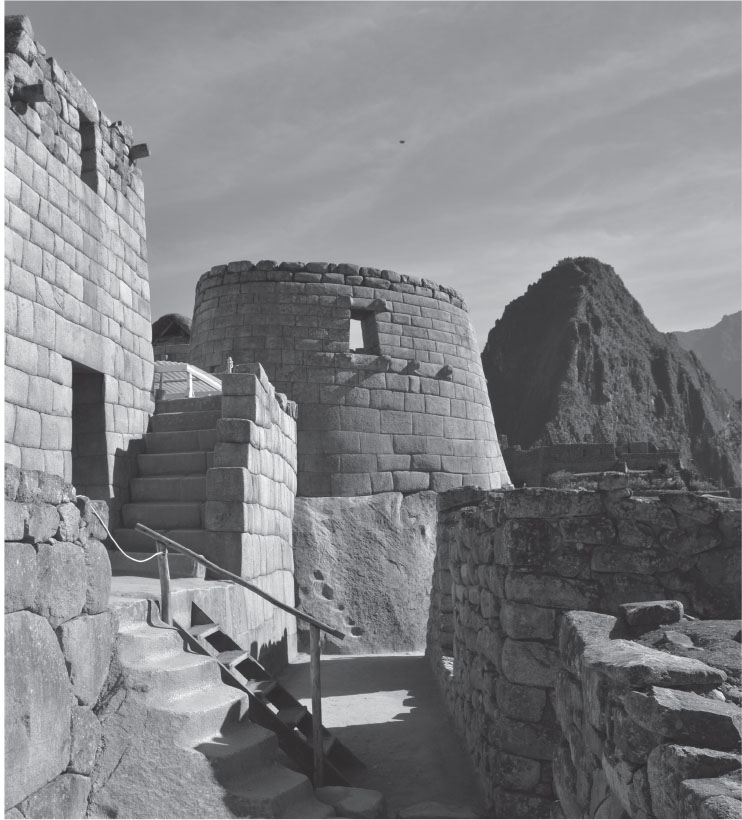

Observatory, 1450–1540, granite, Peru (Figure 26.9b)

Figure 26.9b: Observatory, 1450–1540, granite, Peru

Form

■Ashlar masonry.

■Highest point at Machu Picchu.

Function

■Used to chart the sun’s movements; also known as the Temple of the Sun.

■Left window: sun shines through on the morning of the winter solstice.

■Right window: sun shines through on the morning of the summer solstice.

■Devoted to the sun god.

Intihuatana Stone, 1450–1540, granite, Peru (Figure 26.9c)

Figure 26.9c: Intihuatana Stone, 1450–1540, granite, Peru

■Intihuatana means “hitching post of the sun”; aligns with the sun at the spring and the autumn equinoxes, when the sun stands directly over the pillar and thus creates no shadow.

■Inkan ceremonies held in concert with this event.

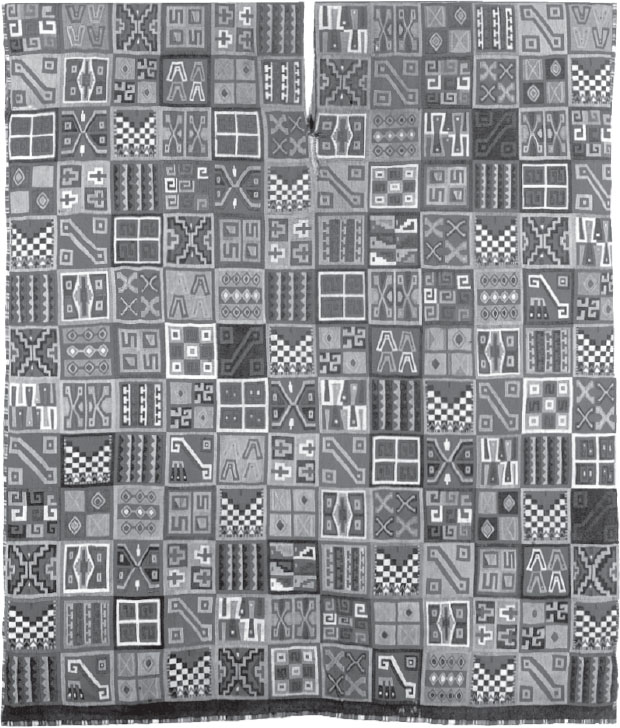

All-T’oqapu tunic, Inka, 1450–1540, camelid fiber and cotton, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. (Figure 26.10)

Figure 26.10: All-T’oqapu tunic, Inka, 1450–1540, camelid fiber and cotton, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

Form

■Rectangular shape; a slit in the center is for the head; then the tunic is folded in half and the sides are sewn for the arms.

■The composition is composed of small rectangular shapes called t’oqapu.

■Individual t’oqapu may be symbolic of individuals, events, or places.

■This tunic contains a large number of t’oqapu.

Function

■Wearing such an elaborate garment indicates the status of the individual.

■May have been worn by an Inkan ruler.

Technique

■Woven on a backstrap loom.

■One end of the loom is tied to a tree or a post and the other end around the back of the weaver.

■The movement of the weaver can create alternating tensions in the fabric and achieve different results.

Context

■Exhibits Inkan preference for abstract designs, standardization of designs, and an expression of unity and order.

■Finest textiles made by women, a highly distinguished art form; this tunic has a hundred threads per square centimeter.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 162

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Status Symbols

–Rank badge of Sin Sukju (Figure 24.6)

–Nun’s badge in Portrait of Juana Inés de la Cruz (Figure 18.6)

–Looped fibulae (Figure 10.1)

NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN ART

Local products form the basis of most North American art forms: wood in the Pacific Northwest; clay, plant fibers, and wool in the American Southwest; and hides in areas populated by large animals like bison and deer. As with most nomadic or semi nomadic peoples (although the Southwest Indians lived in large pueblos or cliff dwellings with fairly sophisticated agricultural programs), geometric designs on ceramics and utilitarian objects and highly decorated fabric with beading and weaving mark their art. Plains Indians even illustrated hides to relate myths and events pertinent to their tribal histories. As the influence of the European settlers spread throughout the Indian nations, native Indian artists were keen to adapt their traditional art forms to new media introduced from abroad. The Europeans also brought with them a curiosity about native art forms, and acted as collectors and patrons for works that appealed to their sensibilities. Thus native American artists, like Cadzi Cody in hide painting and Maria Martínez in ceramics, began serving an emerging tourist industry that appreciated their artistry.

Bandolier bag, Lenape (Delaware tribe, Eastern Woodlands), c. 1850, beadwork on leather, Museum of the American Indian (Figure 26.11)

Figure 26.11: Bandolier bag, Lenape (Delaware tribe, Eastern Woodlands), c. 1850, beadwork on leather, Museum of the American Indian

Form

■The bandolier bag has a large, heavily beaded pouch with a slit on top.

■The bag was held at hip level with strap across the chest.

■The bag was constructed of trade cloth: cotton, wool, velvet, or leather.

Function

■It was made for men and women; objects of prestige.

■They were made by women.

■Functional and beautiful; acted also as a status symbol as part of an elaborate garb.

■Bandolier bags are still made and worn today.

Context

■Beadwork not done in the Americas before European contact.

■Beads and silk ribbons were imported from Europe.

■The bags contain both Native American and European motifs.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 163

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/319100

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Functional Works of Art

–Niobides Krater (Figures 4.19a, 4.19b)

–Navigation chart (Figure 28.3)

–Duchamp, Fountain (Figure 22.9)

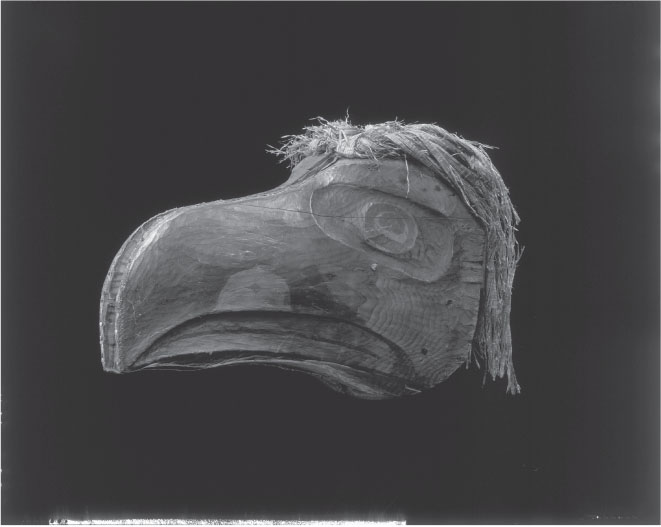

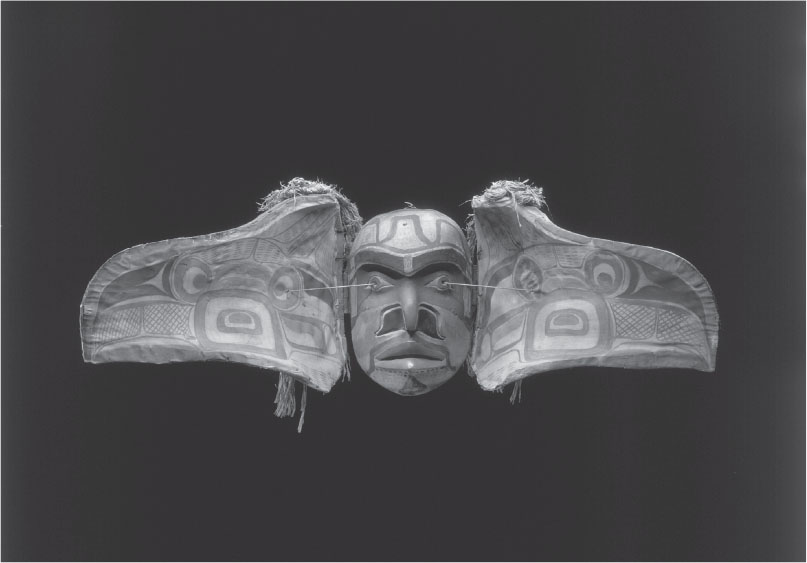

Transformation mask, Kwakwaha’wakw, Northwest Coast of Canada, late 19th century, wood, paint, and string, Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France (Figures 26.12a and 26.12b)

Figure 26.12a: Transformation mask, Kwakwaha’wakw, Northwest Coast of Canada, late 19th century, wood, paint, and string, Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France

Figure 26.12b: Interior of Transformation mask

Form

■The mask has a birdlike exterior face; when opened, it reveals a second human face on the interior.

Function

■The masks were worn by native people of the Pacific. Northwest, centered on Vancouver Island.

■They were worn over the head as part of a complete body costume.

Context

■During a ritual performance, the wearer opens and closes the transformation mask using strings.

■At the moment of transformation, the performer turns his back to the audience to conceal the action and heighten the mystery.

■Opening the mask reveals the face of an ancestor; there is an ancestral element to the ceremony.

■Although these masks could be used at a potlatch, most often they were used in winter initiation rites ceremonies.

■The ceremony is accompanied by drumming and takes place in a “big house.”

■Masks are highly prized and often inherited.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 164

Web Source https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8WREmWxggU&list=PLoAgj1OfSJXMElG4mKifqwfnz0TrISinA&index=2

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Human and Animal Hybrids

–Sphinx (Figure 3.6a)

–Running horned woman (Figure 1.9)

–Mutu, Preying Mantra (Figure 29.25)

Attributed to Cotsiogo (Cadzi Cody), Painted elk hide, Eastern Shoshone, Wind River Reservation, Wyoming, c. 1890–1900, painted elk hide, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York (Figure 26.13)

Figure 26.13: Attributed to Cotsiogo (Cadzi Cody), Painted elk hide, c. 1890–1900, painted elk hide, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Content

■Depicts traditional aspects of the Plains people’s culture that were nostalgic rather than practical: bison hunted with bow and arrow—nomadic hunting gone; bison nearly extinct.

■Hide paintings mark past events.

■Bison considered to be gifts from the Creator.

■Horses, in common use around 1750, liberated the Plains people.

■Teepee: made of hide stretched over poles:

–Exterior poles reach the spirit world or sky.

–Fire represents the heart.

–The doorway faces east to greet the new day.

■The sun dance was conducted around a bison head, and was outlawed by the U.S. government; viewed as a threat to order.

■The sun dance involved men dancing, singing, preparing for the feast, drumming, and constructing a lodge. They honored the Creator deity for the bounty of the land.

■The warrior’s deeds were celebrated on the hide.

Function

■Worn as a robe over the shoulders of the warrior.

■Perhaps a wall hanging.

Context

■Depicts biographical details; personal accomplishments; heroism; battles.

■Men painted hides to narrate an event.

■Eventually, painted hides were made for European and American markets; tourist trade.

■Used paint and dyes obtained through trade.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 165

Web Source https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/tipi/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Animal Imagery

–Apollo 11 stones (Figure 1.7)

–Aka elephant mask (Figure 27.12)

–Muybridge, The Horse in Motion (Figure 21.5)

Maria Martínez and Julian Martínez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel, Tewa, Puebloan, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, mid-20th century, blackware ceramic, Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C. (Figure 26.14)

Figure 26.14: Maria Martínez and Julian Martínez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel. Tewa, Puebloan, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, mid-20th century, blackware ceramic, Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.

Form

■Black-on-black vessel.

■Highly polished surface.

■Contrasting shiny black and matte black finishes.

■Exceptional symmetry; walls of even thickness; surfaces free of imperfections.

Function

■Comes from the thousand-year-old tradition of pottery making in the Southwest.

■Maria Martínez preferred making pots using a new technique that rendered a vessel lightweight, less hard, and not watertight, as traditional pots were; this kind of vessel reflected the market shift away from utilitarian vessels to decorative objects.

Technique

■Used a mixture of clay and volcanic ash.

■The surface was scraped to a smooth finish with a gourd tool and then polished with a stone.

■Julian Martínez painted designs with a liquid clay that yielded a matte finish in contrast with the high shine of the pot itself.

Context

■At the time of production, pueblos were in decline; modern life was replacing traditional life.

■Artists’ work sparked a revival of pueblo techniques.

■Maria Martínez, the potter, developed and invented new shapes beyond the traditional pueblo forms.

■Julian Martínez, the painter of the pots, revived the use of ancient mythic figures and designs on the pots.

■Reflects an influence of Art Deco designs popular at the time.

Content Area Indigenous Americas, Image 166

Web Sources http://www.mariajulianpottery.com/mariamartinezbio.html and https://nmwa.org/works/martinez-jar

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Limited Color

–Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds (Figure 29.27)

–Mblo (Figure 27.7)

–Shiva as Lord of Dance (Figure 23.6)

VOCABULARY

Ashlar masonry: carefully cut and grooved stones that support a building without the use of concrete or other kinds of masonry (Figure 26.8b)

Bandolier bag: a large heavily beaded pouch with a slit on top worn at the waist with a strap over the shoulders (Figure 26.11)

Chacmool: a Mayan figure that is half-sitting and half-lying on his back

Corbel arch: a vault formed by layers of stone that gradually grow closer together as they rise and eventually meet

Coyolxauhqui: an Aztec moon goddess whose name means “Golden Bells” (Figure 26.5b)

Huitzilopochtli: an Aztec god of the sun and war; sometimes represented as an eagle or as a hummingbird

Kiva: a circular room wholly or partly underground used for religious rites

Potlatch: a ceremonial feast among northwest coast American Indians in which a host demonstrates his or her generosity by bestowing gifts

Pueblo: a communal village of flat-roofed structures of many stories that are stacked in terraces; made of stone or adobe (Figure 26.3)

Relief sculpture: a sculpture that projects from a flat background (Figure 26.1c)

Repoussé: (French, meaning “to push back”) a type of metal relief sculpture in which the back side of a plate is hammered to form a raised relief on the front (Figure 26.7)

Roof comb: a wall rising from the center ridge of a building to give the appearance of greater height (Figure 26.2a)

Teepee: a portable Indian home made of stretched hides placed over wooden poles

Tlaloc: ancient American god who was highly revered; associated with rain, agriculture, and war

T’oqapu: small rectangular shapes in an Inkan garment (Figure 26.10)

Transformation mask: A mask worn in ceremonies by people of the Pacific Northwest, Canada, or Alaska. The chief feature of the mask is its ability to open and close, going from a bird-like exterior to a human-faced interior (Figures 26.12a and 26.12b)

SUMMARY

It is difficult to condense into a simple format the complex nature of ancient American civilizations. Some societies were nomadic and produced portable works of art that were meant for ceremonial use. Others established great cities in which ceremonial centers were carefully designed to enhance religious and secular concerns.

Each society of Indians used the local available materials to create their works. Indians from rich forest lands produced huge totem poles that symbolized the spirit of the living tree as well as the gods or legends carved upon them. Those from drier climates made use of adobe for their building material, as in the desert Southwest, or earthenware for fancifully decorated jugs and pitchers. The great cities of Mesoamerica are hewn from stone to create a symbol of permanence and stability in cultures that were more often than not dynamic and in flux.

It is common in ancient America for societies to build on the foundations of earlier cultures. Thus new cities spring from the ruins of the old, as pyramids are built over smaller structures on the same site.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.Transformation masks are best understood as works

(A)used as centerpieces in homes

(B)that are seen as part of a larger ceremony

(C)used to recall ancestral spirits to cast a spell on the wearer’s behalf

(D)used as a display much the same way that totem poles are used

2.Native American artworks often show the influence of Europeans in that they

(A)used European materials in their work

(B)portrayed European historical events with their own histories

(C)adapted European faith traditions and abandoned Native American imagery in their work

(D)experimented with European artistic techniques such as contrapposto and chiaroscuro

3.The image of Coyolxauhqui was carved on a round disk and placed

(A)at the top of an Aztec pyramid so people could worship it

(B)at the entrance to an Aztec temple complex so people could see to whom the complex was dedicated

(C)at the base of a pyramid so sacrificial victims could reenact the fate of Coyolxauhqui

(D)in the coronation room of the king so that his ancestral lineage could be observed by all

4.The Hide Painting of a Sun Dance attributed to Cotsiogo is painted on the same kind of surface as

(A)Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace

(B)The Book of Lindisfarne

(C)Folio from a Qur’an

(D)The Court of Gayumars

5.The Hide Painting of a Sun Dance attributed to Cotsiogo draws on Native American traditions

(A)in its use of the repoussé technique

(B)in that it shows great virtuosity in the handling of classical forms

(C)of articulating forms by placing them in an active sequence around a given space

(D)that place humans on an exaggerated scale dominating all other figures in a work

Short Essay

Practice Question 4: Contextual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

This is the Lanzón Stone from Chavín de Hunántar.

Describe the original placement of the Lanzón Stone.

Using at least two examples of contextual evidence, explain how the siting of the work has influenced the choice of materials and imagery.

Using at least two examples of contextual evidence, explain how the work relates to the site as a whole.

ANSWER KEY

1.B

2.A

3.C

4.B

5.C

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(B) Transformation masks were only one part of a much larger ceremony of Kwakwaha’wakw Indians.

2.(A) When the Europeans settled in America, they often traded their materials for things the Indians valued. The bandolier bag, for example, is made from beads imported from Europe.

3.(C) The disk containing the image of Coyolxauhqui was placed at the bottom of a pyramid. The Aztecs sacrificed people and then threw them down the pyramid the way Huitzilopochtli did to Coyolxauhqui. There was a relationship established between the death and decapitation of Coyolxauhqui and the sacrifice of Aztec enemies at the top of the pyramid.

4.(B) Both the hide painting and The Book of Lindisfarne were executed on animal skins.

5.(C) Native American art often places figures in an active sequence around a given space.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Describe the original placement of the Lanzón Stone. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■The stone was placed inside the temple Chavín at the center of a mazelike system of hallways. ■The stone is underground and in a dark area. |

Using at least two examples of contextual evidence, explain how the siting of the work has influenced the choice of materials and imagery. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■The blade shape of the stone might reflect a plough used for farming; hence the role of the god in ensuring a successful crop. ■The figure carved on the surface is part human (body) and part animal (claws, fangs), with the head of snakes and the face of jaguars. ■Figure done in flat relief. ■Served as a cult figure with limited access. ■Granite was chosen for its durable qualities. |

Using at least two examples of contextual evidence, explain how the work relates to the site as a whole. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■Center of pilgrimage. ■May have been an oracle. ■Stone is buried beneath a large temple presumably dedicated to the gods. ■The whole complex was a religious center. |