Indian and Southeast Asian Art

TIME PERIOD: FROM ANCIENT TIMES TO THE PRESENT

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Sheik to Kings)

Essential Knowledge:

■The art of India is some of the oldest in the world with the longest continuous tradition.

■Indian artists employ a wide range of materials including ceramics and metal.

■Distinctive to India is the development of Buddhist stupas.

■Indian art extensively employs stone and wood carving.

■Indian art specializes in wall and manuscript painting.

■Tapestry is an Indian specialty.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Lakshmana Temple)

Essential Knowledge:

■The Indus Valley civilizations were among the most advanced for their time.

■Cultural centers in India became the home of great civilizations and dynasties.

■Some of the world’s greatest philosophies and religions developed in India.

■Early Indian religions often separated the cosmic from the earthly realm. All the religions in this area (i.e., Hinduism and Buddhist) adopted this world view.

■The Indian religions generated unique artistic expressions, such as the Buddhist stupa and the Hindu temple.

■Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism are image-friendly religions.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Jowo Rinpoche)

Essential Knowledge:

■Indian art has a rich tradition of depicting mythical and historical subjects.

■Architecture is generally religious.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Sheik to Kings)

Essential Knowledge:

■Asian art is influenced by global trends, and in turn influences global trends.

■Trade routes connected Asia with the world.

■Other religions such as Christianity and Islam have had a dramatic impact on the arts in India.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Angkor Wat)

Essential Knowledge:

■Art history as a science is subject to differing interpretations and theories that change over time.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The fertile Indus and Ganges valleys were too great a temptation for outsiders, and thus the history of India has become a history of invasions and assimilations. But those who invaded came to stay, and so Indian life today is a layering of disparate populations to create a cosmopolitan culture. There are eighteen official languages in India—Hindi, the one foreigners think of as the national language, is spoken natively by only 20 percent of the population. Along with Hindus and Muslims, there are many concentrations of Jains, Buddhists, Christians, and Sikhs, as well as myriad tribal religions. Geographically, India has enormous range as well, from the world’s tallest mountains to vast deserts and tropical forests. This is one of the most diverse countries on earth.

Patronage and Artistic Life

The arts play a critical role in Indian life. Most rulers have been extremely generous patrons, commissioning great buildings, sculptures, and murals to enhance civic and religious life, as well as their own glory. The interconnectiveness of the arts in India is crucial to understanding Indian artistic life. Monuments are conceived as a combination of the arts; the artists who work on them carry out their work at the behest of an artist who acts as a team leader with a single artistic vision. Thus, Indian monuments have a surprising uniformity of style. The design of religious art and architecture may have also been determined by a priest or other religious advisor, who ensured that proportions and iconography of monuments agreed with descriptions supplied in canonical texts and diagrams.

Much as in the European tradition, artists were trained as apprentices in workshops. The process was comprehensive; the artist learned everything from how to make a brush to how to create intricate miniatures or vast murals. Indians are highly organized in their approach to artistic training.

BUDDHIST PHILOSOPHY AND ART

Still practiced today as the dominant religion of Southeast Asia, Buddhism is a spiritual force that teaches individuals how to cope in a world full of misery. The central figure, Buddha (563–483 B.C.E.), who is not a god, rejected the worldly concerns of life at a royal court, and sought fulfillment traveling the countryside and living as an ascetic.

In Buddhism, life is believed to be full of suffering that is compounded by an endless cycle of birth and rebirth. The aim of every Buddhist is to end this cycle and achieve oneness with the supreme spirit, which involves a final release or extinguishing of the soul. This can only happen by accumulating spiritual merit through devotion to good works, charity, love of all beings, and religious fervor.

Buddhist art has a rich cultural iconography. Some of the most common symbols include:

■The Lion: a symbol of Buddha’s royalty

■The Wheel: Buddha’s law

■Lotus: a symbol of Buddha’s pure nature. The lotus grows in swamps, but mud slides off its surface.

■Columns surrounded by a wheel: Buddha’s teaching

■Empty Throne: Buddha, or a reminder of a Buddha’s presence.

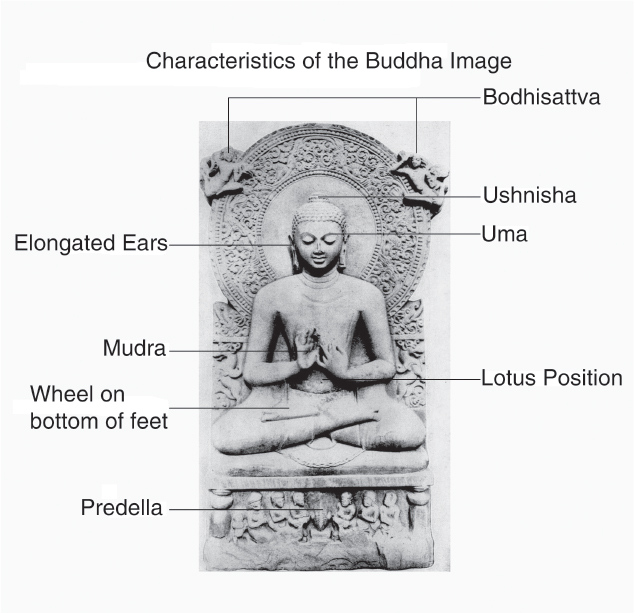

Figure 23.1: Principal characteristics of the Buddha

There is a surprising uniformity in the way in which Buddhas are depicted, given that they were produced over thousands of years and across thousands of miles. Typically Buddhas have a compact pose with little negative space (Figure 23.1). They are often seated, although standing and lying down are occasional variations. When seated, a Buddha is usually posed in a lotus position with the balls of his feet turned straight up, and a wheel marking on the souls of the feet is prominently displayed.

The treatment of drapery varies from region to region. In Central India, Buddhist drapery is extremely tight-fitting, and resting on one shoulder with folds slanting diagonally down the chest. In Gandhara, a region that spreads across northwest India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, Buddhist figures wear heavy robes that cover both shoulders, similar to a Roman toga, showing a Hellenistic influence.

Buddhas are generally frontal, symmetrical, and have a nimbus, or halo, around their heads. Helpers, called bodhisattvas, are usually near the Buddha, sometimes attached to the nimbus.

Buddhas’ moods are many, but most have a detached, removed quality that suggests meditation. Buddhas’ actions and feelings are revealed by hand gestures called mudras.

The head has a top knot, or ushnisha, and the hair has a series of tight-fitting curls. Extremely long ears dangle almost to his shoulders. A curl of hair called an urna appears between his brows. His rejection of courtly life explains his disdain for personal jewelry.

Beneath statues of Buddha there usually is a base or a predella, which can include donor figures and may have an illustration of one of his teachings or a story from his life.

Buddhist art also depicts distinctive figures called yakshas (males) and yakshis (females), which are nature spirits that appear frequently in Indian popular religion. Their appearance in Buddhist art indicates their incorporation into the Buddhist pantheon. The females often stand in an elaborate dance-like poses, almost nude, with their breasts prominently displayed. The depiction of yakshas accentuates male characteristics such as powerful shoulders and arms.

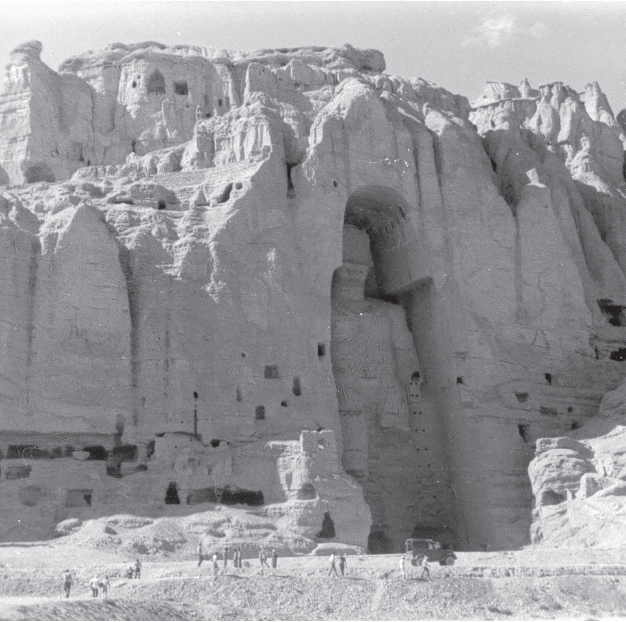

Buddha from Bamiyan, Gandharan, 400–800, destroyed 2001, cut rock with plaster and polychrome paint, Afghanistan (Figures 23.2a and 23.2b)

Figure 23.2a: Buddha from Bamiyan, Gandharan, 400–800, destroyed 2001, cut rock with plaster and polychrome paint, Afghanistan

Figure 23.2b: Buddha from Bamiyan, oblique view

Form and Content

■ First colossal Buddhas.

■ Two huge standing Buddhas, one 175 feet tall, the other 115 feet tall.

■ Smaller Buddha: Sakyamuni, the historical Buddha.

■ Larger Buddha: Vairocana, the universal Buddha.

■ Niche shaped like a halo—or mandorla—around the body.

■ Buddhas originally covered with pigment and gold.

■ Cave galleries weave through the cliff face; some contain wall paintings and painted images of the seated Buddha.

Function

■ Pilgrimage site linked to the Silk Road.

■ Pilgrims can walk through the cave galleries into passageways that lead to the level of the Buddha’s shoulders.

■ Legs are carved in the round; originally pilgrims were able to circumambulate.

■ Caves were part of a vast complex of Buddhist monasteries, chapels, and sanctuaries.

Context

■ Located near one of the largest branches of the Silk Road.

■ Bamiyan, situated at the western end of the Silk Road, was a trading and religious center.

■ These Buddhas served as models for later large-scale rock-cut images in China.

■ Destroyed by the Taliban in an act of iconoclasm in March 2001.

Content Area West and Central Asia, Image 182

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/208

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Monumental Sculpture

–Lamassu (Figure 2.5)

–Great Sphinx (Figure 3.6a)

–Longmen Caves (Figure 24.9a)

Jowo Rinpoche enshrined in the Jokhang Temple, Yarlung Dynasty, believed to have been brought to Tibet in 641, gilt metals with semiprecious stones, pearls, and paint; various offerings, Lhasa, Tibet (Figure 23.3)

Figure 23.3: Jowo Rinpoche enshrined in the Jokhang Temple, Yarlung Dynasty, believed to have been brought to Tibet in 641, gilt metals with semiprecious stones, pearls, and paint; various offerings, Lhasa, Tibet

History

■ Statue thought to have been blessed by the Buddha himself; believed to have been crafted in India during his lifetime; said to have his likeness.

■ Believed to have been brought to Tibet in 641.

■ Temple founded in 647 by the first ruler of a unified Tibet.

■ Disappeared in 1960s during China’s Cultural Revolution.

■ In 1983, the lower part was found in a rubbish heap and the upper part in Beijing; restored in 2003.

■ Enshrined in the Jokhang Temple, Tibet’s earliest and foremost Buddhist temple.

Function

■ Served as a proxy for the Buddha after his departure from this world.

■ Often decorated, clothed, and presented with offerings.

Context

■ Depiction of Buddha Sakyamuni as a young man around the age of twelve.

■ Most sacred and important Buddhist image in Tibet.

■ Jowo means “lord,” Khang means “house.”

Content Area West and Central Asia, Image 184

Web Source for Buddhist Art http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/budd/hd_budd.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Sacred Images

–Moai (Figure 28.11)

–Apollo from Veii (Figure 5.5)

–Reliquary of Sainte-Foy (Figure 11.6c)

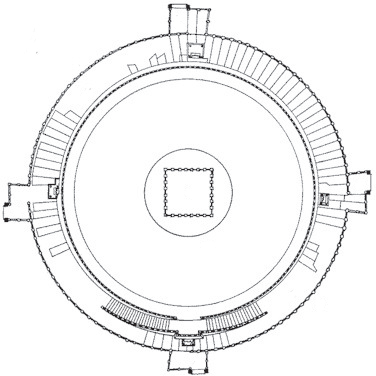

BUDDHIST ARCHITECTURE

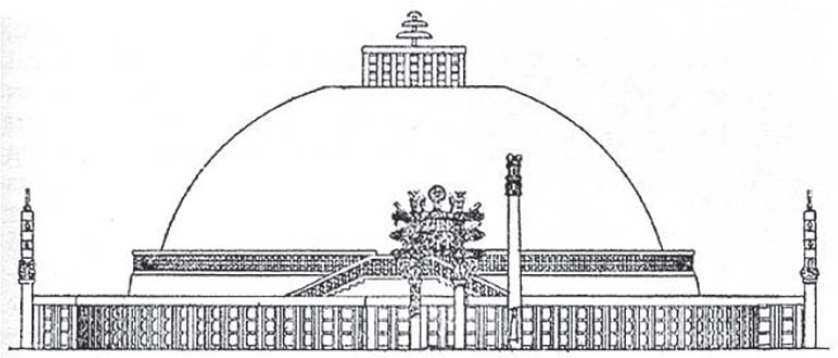

The principal place of early Buddhist worship is the stupa, a mound-shaped shrine that has no interior. A stupa is a reliquary; worshippers gain spiritual merit through being in close proximity to its contents. A staircase leads the worshipper from the base to the drum. Buddhists pray while walking in a clockwise or easterly direction, that is, the direction of the sun’s course. Because of its distinctive shape, that of a giant hemisphere, and because one walks and prays with the sun, the stupa has cosmic symbolism. It is also conceived as being a symbol of Mt. Meru, the mountain that lies at the center of the world in Buddhist cosmology and serves as an axis connecting the earth and the heavens.

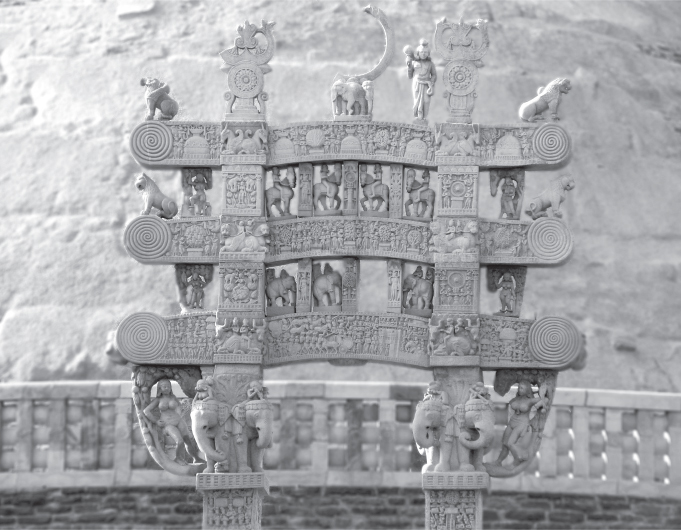

Stupas, like one at Sanchi (Figure 23.4a), have a central mast of three umbrellas at the top of the monument, each umbrella symbolizing the three jewels of Buddhism: the Buddha, the Law, and the Community of Monks. The square enclosure around the umbrellas symbolizes a sacred tree surrounded by a fence.

Four toranas, at the cardinal points of the compass, act as elaborate gateways to the structure.

Great Stupa, Buddhist, Mauyra, late Sunga Dynasty, 300 B.C.E.–100 C.E., stone masonry, sandstone on dome, Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh, India (Figures 23.4a, 23.4b, 23.4c, 23.4d, 23.4e)

Figure 23.4a: Great Stupa, Buddhist, Mauyra, Late Sunga Dynasty, 300 b.c.e.–100 c.e., stone masonry, sandstone on dome, Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh, India

Figure 23.4b: Interior ambulatorye

Figure 23.4c: North Gate, or Torana

Figure 23.4d: Great Stupa plan

Figure 23.4e: Great Stupa elevation

Function

■Pilgrimage site.

■A Buddhist shrine, mound shaped and faced with dressed stone containing the relics of the Buddha.

■The worshipper circumambulates the stupa clockwise along the base of the drum; circular motion suggests the endless cycle of birth and rebirth.

Form

■Three umbrellas at the top represent Buddha, Buddha’s law, and monastic orders.

■A railing at the crest of the mound surrounds the umbrellas, symbolically representing a sacred tree.

■Double stairway at the south end leads from base to drum, where there is a walkway for circumambulation.

■Originally painted white.

■Hemispherical dome is a replication of the dome of heaven. Seated Buddha from second level from the Later Gupta period.

Toranas

■Four toranas, or gateways, at cardinal points of the compass, grace the entrances.

■The orientation of the toranas (east, south, west, and north) and the direction of ritualistic circumambulation correspond with the direction of the sun’s course: from sunrise to zenith, sunset, and nadir.

■Torana: richly carved scenes on the architraves:

–Buddha does not appear himself but is symbolized by an empty throne or a tree under which he meditated.

– Some of these reliefs may also represent the sacred sites where Shakyamuni Buddha visited or taught others about the jataka stories or past lives of the Buddha.

– Horror vacui of composition.

– High-relief sculpture.

– Pre-Buddhist Yakshi figures symbolize fertility.

Context

■ Donors’ names are carved into the monument: 600 inscriptions reveal the project was funded by women as well as men, common people as well as monks.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 192

Web Source http://sanchi.org/sanchi-great-stupa.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Integration of Sculpture and Architecture

– Angkor Wat (Figures 23.8a, 23.8b, 23.8c, 23.8d)

– Parthenon (Figures 4.5, 4.6)

– Mortuary temple of Hatshepsut (Figure 3.9a)

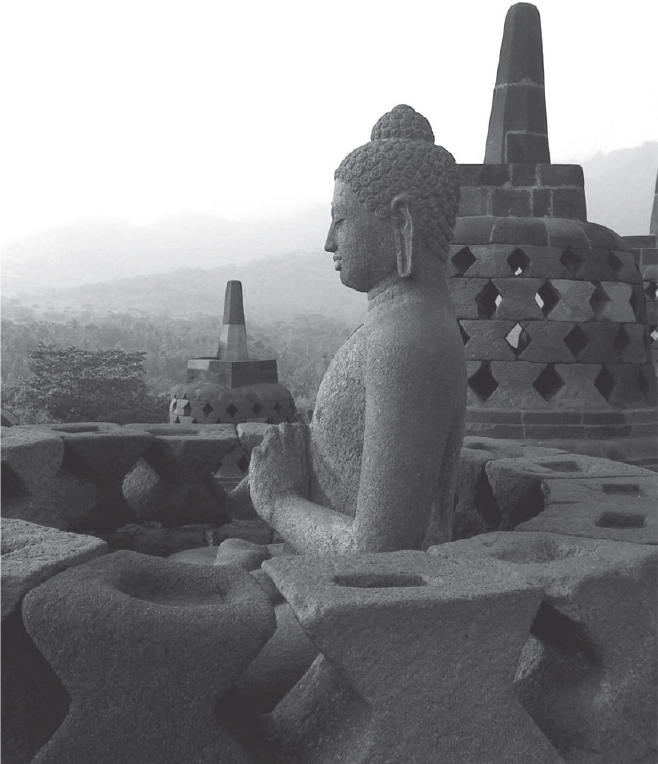

Borobudur Temple, Sailendra Dynasty, c. 750–842, volcanic stone masonry, Central Java, Indonesia (Figures 23.5a, 23.5b, and 23.5c)

Figure 23.5a: Borobudur Temple, Sailendra Dynasty, c. 750–842, volcanic stone masonry, Central Java, Indonesia

Figure 23.5b: Borobudur Temple: Queen Maya riding a horse carriage retreating to Lumbini to give birth to Prince Siddhartha Gautama

Figure 23.5c: Borobudur Temple, Buddha

Form

■ Pyramid in form; aligned with the four cardinal points of the compass.

■ Square-shaped plan with four entry points.

■ Rubble faced with carved volcanic stone.

■ Built on a low hill rising above a wide plain.

Content

■ This massive Buddhist monument contains 504 life-size Buddhas, 1,460 narrative relief sculptures on 1,300 panels 8,200 feet long.

■ 72 openwork stupas containing a Buddha, each with a preaching mudra.

■ Six identical square terraces are placed one atop the other, like steps; three smaller circular terraces are placed on top; the lowest level functions as the base of the structure, with a square floor plan; the second level recedes 23 feet from the edge of the base so that the space is wide enough for processions.

■ Each terrace is a level of enlightenment.

■ On the top is an enclosed stupa.

■ Divided into three sections, representing three levels of Buddhist cosmology:

– Base: represents the lowest level of experience; those who are aligned with their desires on Earth; the world of desire and negative impulses; sculptures here show the deeds of self-sacrifice practiced by the Buddha in his previous births and the story of his last incarnation as Prince Siddhartha.

– Body: five terraces in which people abandon their earthly desires; this is the world of forms—people have to control these negative impulses; sculptures here show the pilgrimage of the young man, Sudhana, who sets out in search of the Ultimate Truth.

– Superstructure: an area that represents a formless world, in which a person experiences reality in its purest stage, where the physical world and worldly desire are expunged.

Function

■ A place of pilgrimage.

■ Built as a stupa.

Context

■ Meant to be circumambulated on each terrace; six concentric square terraces topped by three circulaSr tiers with a great stupa at the summit.

■ Iconographically complex and intricate; many levels of meaning.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 198

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Pilgrimage Sites

– Church of Sainte-Foy, Conques (Figures 11.4a, 11.4b)

– the Kaaba (Figures 9.11a, 9.11b)

– Great Stupa (Figures 23.4a, 23.4b)

Queen Maya riding a horse carriage retreating to Lumbini to give birth to Prince Siddhartha Gautama

■ Densely packed scene; horror vacui.

■ The queen is majestic and at rest before giving birth.

■ Ready to give birth to her son, Prince Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha.

■ She is brought to the city in a great ceremonial procession.

Web Source http://borobudurpark.com/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Relief Sculpture

– Plaque of the Ergastines (Figure 4.5)

– Wall plaque from Oba’s palace (Figure 27.3)

– Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus (Figure 6.17)

HINDU PHILOSOPHY AND ART

To outsiders, Hinduism is a bewildering religion with myriad sects, each devoted to the worship of one of its many gods. The complexity and multiplicity of the practices and beliefs associated with Hinduism are evident in the name of the religion, which is an umbrella term meaning, “the religions of Hindustan (India).” Folk beliefs exist side by side with sophisticated philosophical schools. However, all forms of Hinduism concentrate on the infinite variety of the divine, whether it is expressed in the gods, in nature, or in other human beings. Those who proclaim to be orthodox Hindus accept the Vedic texts as divine in origin, and many maintain aspects of the Vedic social hierarchy, which assigns a caste of ritual specialists, known as Brahmins, to officiate between the gods and humankind.

As in the case of Buddhism, every Hindu is to lead a good life through prayer, good deeds, and religious devotion, because only in that way can he or she break the cycle of reincarnation. Shiva (Figure 23.6) is one of the principal Hindu deities, who periodically dances the world to destruction and rebirth. Other important deities include Brahma, the creator god; Vishnu, the preserver god; and the great goddesses who are manifest as peaceful consorts, like Laksmi and Parvati.

HINDU SCULPTURE

Temple sculpture is a complete integration with the architecture to which it is attached—sometimes the buildings are thought of as a giant work of sculpture. Pairs of divine couples, known as mithuna, appear upon the exterior and doorways of some temples. Sexual allusions dominate and are expressed with candor, but not obscenity. Hindu sculptures accentuate sinuous curves and the lines of the body. Dance poses are common. Temple surfaces are also ornamented with organic and geometric designs, including lateral bands that depict subjects such as lotus flowers, temple bells, and strings of pearls.

Images placed in the “womb” of the temple are idols in that they are invoked with the essence of divinity that the figure represents. To touch the image is to touch the god himself or herself; few can do this. Instead the image is treated with the utmost respect and deference, and is occasionally exposed to public viewing. Worshippers experience the divine through actively seeing the invoked image, an experience known as darshan and performing puja, a ritual offering to the deity, which is mediated by temple priests.

Shiva as Lord of Dance (Nataraja), Hindu, India (Tamil Nadu), Chola Dynasty, c. 11th century C.E., cast bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Figure 23.6)

Figure 23.6:Shiva as Lord of Dance (Nataraja), Hindu, India (Tamil Nadu), Chola Dynasty, c. 11th century c.e., cast bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

■ Shiva has four hands.

■ One hand sounds the drum that he dances to; another carries a flame of destruction; the other two offer the abhaya mudra, a gesture that allays fear.

■ Epicene quality showing an idealized, nearly nude, male figure.

■ Flying locks of hair terminate in rearing cobra heads.

■ Often depicted in a flaming nimbus, vigorously dancing with one foot on a dwarf, the Demon of Ignorance.

■ Fire around Shiva represents the borders of the Hindu cosmos; covered with flowers when carried in processions.

Function

■ The sculpture becomes the receptacle for the divine spirit when people pray before it; therefore, the sculpture is royally treated with gifts, food, and incense.

■ The sculpture can be bathed and clothed.

■ A hole is at the bottom of the sculpture for the placement of a pole so that it can be used in processions and covered by flowers.

Context

■ Shiva periodically destroys the universe so that it can be reborn again.

■ He unfolds the universe out of the drum held in one of his right hands; he preserves it by uplifting his other right hand in a gesture indicating “do not be afraid.”

■ Shiva has a third eye barely suggested between his other two eyes; he once burned the god Kama with this eye.

■ The message is that belief in Shiva can achieve salvation.

■ The distribution of this figure due to the patronage of a queen, Mahadevi.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 202

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39328

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Divine Judgments

– Last judgment of Hunefer (Figure 3.12)

– Last Judgment, Sainte-Foy, Conques (Figure 11.6a)

– Gaulli, Triumph of the Name of Jesus (Figure 17.6)

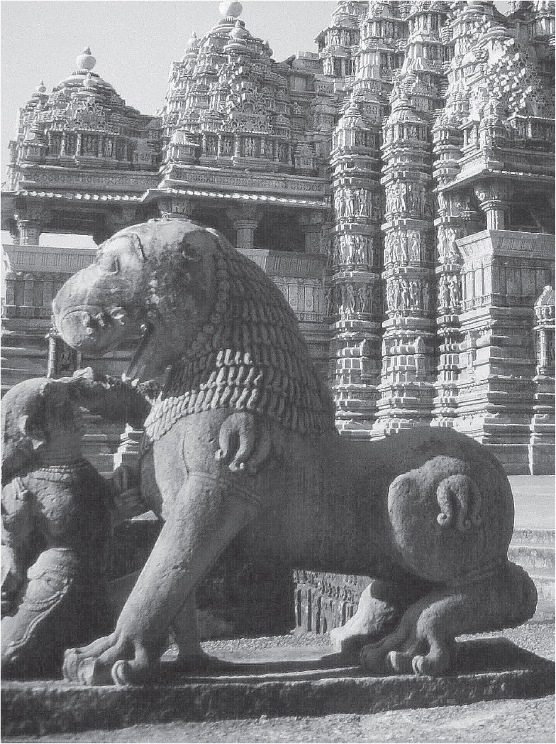

HINDU ARCHITECTURE

The Hindu temple is not a hall for congregational worship; instead it is the residence of a god. The temples are solidly built with small interior rooms, just enough space for a few priests and individual worshippers. At the center is a tiny interior cella that is called the “Womb of the World” where the sacred statue invoked with the main deity is placed. Although Indians knew the arch, they preferred corbelled-vaulting techniques to create a cave-like look on the inside. Thick walls protect the deity from outside forces. An antechamber, where ceremonies are prepared, precedes the cella, and a hypostyle hall is visible from the outside where congregants can participate. Hindu temples are constructed amid a temple complex that includes subsidiary buildings.

In northern India, temples have a more vertical character, with large towers setting the decorative scheme, and other subsidiary towers imitating the shape but at various scales. Placed on high pedestals, temples have a sense of grandeur as they command the countryside. Major temples form “temple cities” in south India, where layers of concentric gated walls surround a network of temples, shrines, pillared halls, and colonnades. The Hindu temples found in Cambodia are based upon a pyramidal plan with a central shrine surrounded by subshrines and enclosed walls.

Temple exteriors are covered with sculpture, almost in a feverish frenzy to crowd every blank spot on the surface.

Lakshmana Temple, Hindu, Chandella Dynasty, 930–950, sandstone, Khajuraho, India (Figures 23.7a, 23.7b, 23.7c, 23.7d)

Figure 23.7a:Lakshmana Temple, Hindu, Chandella Dynasty, 930–950, sandstone, Khajuraho, India

Figure 23.7b: Detail of façade of Lakshmana Temple

Figure 23.7c: Detail of Lakshmana Temple

Figure 23.7d: Plan of Lakshmana Temple

Form

■ The temple is placed on a high pedestal, or plinth, to be seen from a distance. It appears like rising peaks of a mountain range.

■ Compact proportions.

■ East/west axis: it receives direct rays from the rising sun.

■ The building is a series of shapes that build to become a large tower; complicated intertwining of similar forms called a shikara.

■ In the center is the “embryo” room containing the shrine.

■ The embryo, called a garbha griha, is very small with only space enough for a limited number of people. It is meant for individual—not congregational—worship.

Materials

■ Ashlar masonry; made of fine sandstone.

Sculpture

■ Bands of horizontal moldings unite the temple.

■ The sculpture on the surface harmoniously integrates with the architecture.

■ The figures are sensuous with revealing clothing.

■ Erotic poses symbolize regeneration.

■ Sexuality is frankly expressed.

Function

■ It is a Hindu temple grouped with a series of other temples in Khajuraho.

■ The temple is dedicated to Vishnu.

Patron

■ Yashovarman, a leader in the Chandella Dynasty, built the temple to legitimize his rule; completed by his son, Dharga, after his death.

Context

■ Worshippers move in a clockwise direction starting at the staircase to circumambulate the temple.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 200

Web Source for Hindu Art http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hind/hd_hind.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ashlar Masonry

– Parthenon (Figure 4.16b)

– Persepolis (Figures 2.6a, 2.6b)

– Petra (Figures 6.9a, 6.9b, 6.9c)

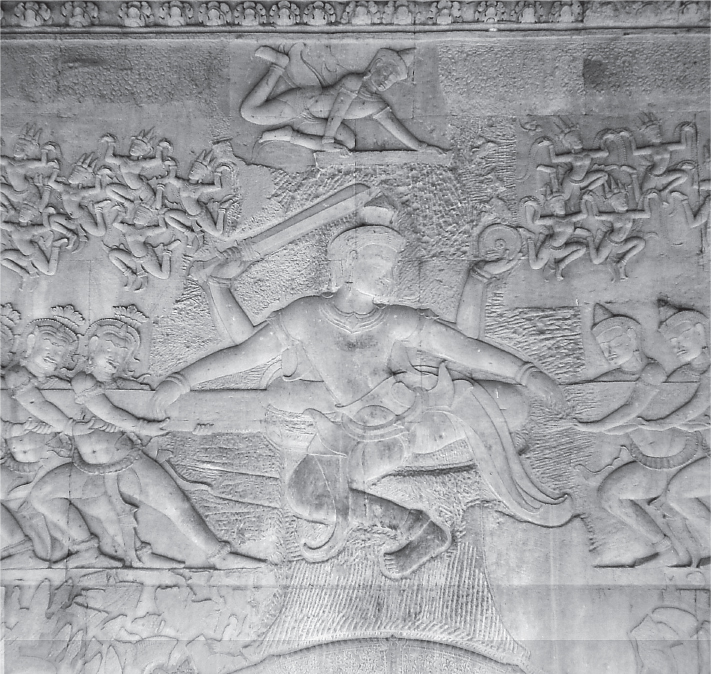

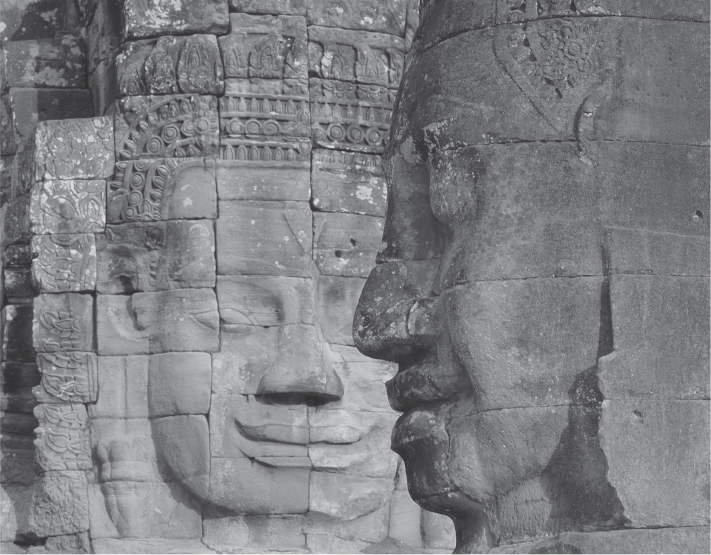

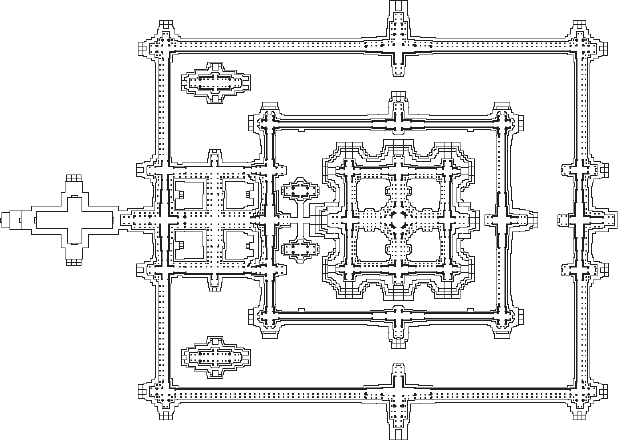

Angkor, the temple of Angkor Wat, and the city of Angkor Thom, Hindu, Angkor Dynasty, c. 800–1400, stone masonry, sandstone, Cambodia (Figures 23.8a, 23.8b, 23.8c, 23.8d, 23.8e)

Figure 23.8a: Angkor Wat, Hindu, Angkor Dynasty, c. 800–1400, stone masonry, sandstone, Cambodia

Figure 23.8b: South Gate of Angkor Thom

Figure 23.8c: Churning of the Ocean of Milk

Figure 23.8d:Jayavarman VII as Buddha

Figure 23.8e: Angkor Wat plan

Form

■ Main pyramid is surrounded by four corner towers; a temple-mountain.

■ Corbelled gallery roofs; influenced by the Indian use of corbelled vaulting.

■ The entire complex is made of stone; most surfaces are carved and decorated.

■ Horror vacui of sculptural reliefs.

■ Sculpture in rhythmic dance poses; repetition of shapes.

Function

■ Dedicated to Vishnu; most sculptures represent Vishnu’s incarnations.

■ May have been intended to serve as the king’s mausoleum.

■ Hindu temples functioned primarily as the home of the god.

Patronage

■ Angkor Wat was the capital of medieval Cambodia, built by King Suryavarman II.

■ The complex was built by successive kings, who installed various deities in the complex.

■ The kings often identified themselves with the gods they installed.

Context

■ The complex has a mixed Buddhist/Hindu character.

■ Mountain-like towers symbolize the five peaks of Mount Meru, a sacred mountain said to be the center of the spiritual and physical universe in both Buddhism and Hinduism.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 199

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Water and Art

– Versailles Gardens (Figure 17.3e)

– Kusama, Narcissus Garden (Figures 22.25a, 22.25b)

– Alhambra (Figure 9.15b)

■ Churning of the Ocean of Milk

– The story is from the Hindu religion.

– The story involves the churning of the ocean of the stars to obtain Amrita, the nectar of immortal life.

– Both the gods (devas) and the devils (asuras) churn the ocean to guarantee themselves immortality.

– To churn the ocean, they used the Serpent King, Vasuki.

– This bas-relief at Angkor Wat depicts devas and asuras churning the Ocean of Milk.

– Vishnu wraps a serpent around Mount Mandara; the mountain rotates around the sea and churns it.

■ Jayavarman VII as Buddha, Khmer king, reigned c.1181–1218

– Most famous and powerful Khmer monarch.

– Patron of Angkor Thom.

– Heavily influenced by his two wives, who were sisters; after his first wife’s death he married her sister.

– Jayavarman was devoted to Buddhism, although these monuments show a mixture of Buddhist and Hindu iconography.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 199

Web Source http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/668/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Gardens

– Versailles Gardens (Figure 17.3e)

– Ryoan-ji (Figures 25.2a, 25.2b, 25.2c)

– Kusama, Narcissus Garden (Figures 22.25a, 22.25b)

PAINTING

Indians excel at painting miniatures, illustrations done with watercolor on paper, used either to illuminate books or as individual leaves kept in an album. One of the most famous schools of Indian painting is the Rajput School, which enjoyed illustrating Hindu myths and legends, especially the life of Krishna. Care is also lavished on individual portraits, which were done with immediacy and freshness.

As in most Indian art, compositions tend to be both crowded and colorful. Perspective is tilted upward so that the surface of objects, like tables or rugs, can be seen in their entirety. Floral patterns contribute to the richness of expression. Figures are painted with great delicacy and generally seem small compared to the landscape around them. They have a doll-like character that adds to the fairy-tale-like nature of the stories being illustrated.

Characteristics of Indian painting include a heightened and intense use of color, with black lines outlining figures. Humans have a wide range of emotion; figures often gesticulate wildly. Nature is seen as friendly and restorative. Few names of Indian artists have come down to us; the works are generally anonymous, even among the greatest masters.

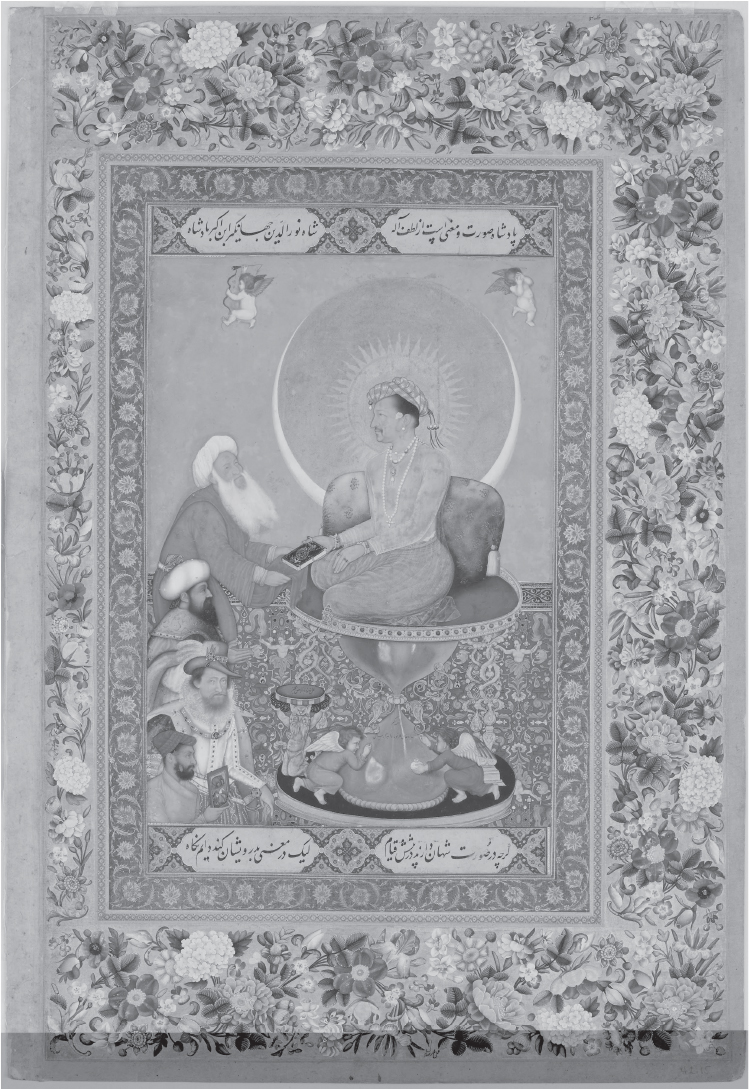

Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings, c. 1620, watercolor, gold, and ink on paper, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (Figure 23.9)

Figure 23.9: Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings, c. 1620, watercolor, gold, and ink on paper, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Content

■ Jahangir is the source of all light; he is surrounded by a halo of the sun and moon.

■ Jahangir is near the end: seated on an hourglass throne; sands of time running out.

■ Jahangir wears a single pearl as a devotion to an eleventh century saint.

■ Sufi Sheik is handed a book by Jahangir, or perhaps the holy man is handing Jahangir the book—the book is placed on a cloth so that the sheik does not touch Jahangir.

■ The sheik was the superintendent of the shrine at Ajmer, where Jahangir lived from 1613–1616.

■ Holy men are placed above and rank higher than all others; the painting is thought to represent the importance of spiritual life over worldly power.

■ The Ottoman sultan (not a real portrait) is placed higher than James I, but shows deference to Jahangir.

■ James I of England is in the lower left-hand corner; less important than Jahangir, as his position implies; the portrait based on a diplomatic gift probably by artist John de Critz, given by ambassador Sir Thomas Roe.

■ The artist, a Hindu, holds a miniature with two horses and an elephant—perhaps gifts from his patron.

■ The artist is in lower left-hand corner; he symbolically signs his name on the footstool beneath Jahangir.

Quotations

■ Quotation, in frame: “Though outwardly shahs stand before him, he fixes his gazes on dervishes.”

■ Angels wish Jahangir a long life by writing on the hourglass, “O Shah, may the span of your life be a thousand years.”

Context

■ Jahangir had many artists follow him wherever he went; he wanted everything recorded.

■ He sought to bring together things from distant lands.

■ Cross-cultural influences from Europe: a Renaissance carpet is in the background; figures of small cherubs are copied from European paintings; there is a halo behind Jahangir.

■ Great interest in the Mughal court for European allegorical portraits, techniques, and motifs.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 208

Web Source www.freersackler.si.edu/object/F1942.15a/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Works that Show Western Influence

– Cotsiogo, Painted elk hide (Figure 26.13)

– Cabrera, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Figure 18.6)

– Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene (Figure 28.7)

VOCABULARY

Ashlar masonry: carefully cut and grooved stones that support a building without the use of concrete or other kinds of masonry (Figure 23.7a)

Bas-relief: a very shallow relief sculpture (Figure 23.5b)

Bodhisattva: a deity who refrains from entering nirvana to help others

Buddha: a fully enlightened being. There are many Buddhas, the most famous of whom is Sakyamuni, also known as Gautama or Siddhartha (Figure 23.5c)

Cella: the main room of a temple, where the god is housed

Darshan: in Hinduism, the ability of a worshipper to see a deity and the deity to see the worshipper

Garbha griha: a “womb chamber,” the inner room in a Hindu temple that houses the god’s image

Horror vacui: (Latin, meaning “fear of empty spaces”) a type of artwork in which the entire surface is filled with objects, people, designs, and ornaments in a crowded and sometimes congested way (Figure 23.5b)

Hypostyle: a hall with a roof supported by a dense thicket of columns

Iconoclasm: the destruction of religious images that are seen as heresy (Figure 23.2)

Mandorla: (Italian, meaning “almond”) an almond-shaped circle of light around the figure of Christ or Buddha (Figure 23.2a)

Mithuna: in India, the mating of males and females in a ritualistic, symbolic, or physical sense (Figure 23.7b)

Mudra: a symbolic hand gesture in Hindu and Buddhist art (Figure 23.1)

Nirvana: an afterlife in which reincarnation ends and the soul becomes one with the supreme spirit

Puja: a Hindu prayer ritual

Sakyamuni: the historical Buddha, named after the town of Sakya, Buddha’s birthplace (Figure 23.3)

Shikara: a bee-hive shaped tower on a Hindu temple (Figure 23.7a)

Shiva: the Hindu god of creation and destruction (Figure 23.6)

Stupa: a dome-shaped Buddhist shrine (Figure 23.4a)

Torana: a gateway near a stupa that has two upright posts and three horizontal lintels. They are usually elaborately carved (Figure 23.4c)

Urna: a circle of hair on the brows of a deity, sometimes represented as focal point (Figure 23.1)

Ushnisha: a protrusion at the top of the head, or the top knot of a Buddha (Figure 23.1)

Vairocana: the universal Buddha, a source of enlightenment; also known as the Supreme Buddha who represents “emptiness,” that is, freedom from earthly matters to help achieve salvation (Figure 23.2a)

Vishnu: the Hindu god worshipped as the protector and preserver of the world (Figure 23.8c)

Wat: a Buddhist monastery or temple in Cambodia (Figure 23.8a)

Yakshi (masculine: yaksha): female and male figures of fertility in Buddhist and Hindu art

SUMMARY

The diversity of the Indian subcontinent is reflected in the wide range of artistic expression one finds there. Indians typically unify the arts, so that one large monument is realized as a single creative expression involving painting, sculpture, and architecture.

Buddhist images dominate early Indian art. Buddha himself is often depicted in a meditative state, with his various mudras revealing his inner thoughts. Hindu sculptures feature a myriad of gods, with Shiva as the most dominant. Both Buddhist and Hindu temples are mound-shaped, the Buddhist works being a large, solid hemisphere, and the Hindu a sculpted mountain with a small interior.

Both Hindu and Buddhist art are marked by horror vacui, forms piled one atop the other in crowded compositions.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

Questions 1–3 refer to these images.

1.The Lakshmana Temple is a Hindu temple that has a narrow interior because

(A)it symbolizes the embryo of the world, as if in its very womb

(B)vaulting techniques were unknown

(C)the narrow passageway symbolizes the journey to salvation

(D)the interior darkness symbolizes the evil in the world

2.Erotic sculptures on the outside of the temple connote

(A)inspiration

(B)regeneration

(C)subjugation

(D)intolerance

3.The highly carved exterior is similar to the complex at

(A)Borobudur, Java

(B)Persepolis, Iran

(C)Todai-ji, Japan

(D)Ryoan-ji, Japan

4.Shiva as Lord of Dance depicts an episode of divine judgment in which Shiva

(A)warns the living that judgment day is coming

(B)judges those who have died and will be sent to heaven or hell

(C) destroys the universe so that it can be reborn again

(D) comforts the weak and disciplines the strong

5.The Bamiyan Buddhas were destroyed in 2001 in an act of

(A)iconography

(B)impluvium

(C)isocephalism

(D)iconoclasm

Short Essay

Practice Question 3: Visual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

This work is Shah Shuja Enthroned with Maharaja Gaj Singh of Marvar by Bichitr.

Describe at least two visual characteristics of this work.

Using specific visual evidence, explain at least two techniques that Bichitr used that are part of Indian portrait tradition.

Discuss how this work references works of art in the Western tradition.

ANSWER KEY

1.A

2.B

3.A

4.C

5.D

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(A) The interiors of Hindu temples are characterized by small rooms that contain the god; they are called the “embryo” of the world and are meant to suggest the very center of existence, among many other things.

2.(B) The erotic sculptures are done with frankness to symbolize regeneration. They are not done to be lurid or sinful.

3.(A) Borobudur has many sculptures, both in relief and free standing, wrapped around its exterior.

4.(C) Shiva periodically dances the world to destruction and rebuilds it so that it can start afresh.

5.(D) Iconoclasm is defined as the destruction of images. The Bamiyan Buddhas were blown up because they were considered false idols.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Describe at least two visual characteristics of this work. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■ Work is framed in an elaborate border. ■ There is a tilted perspective: we look directly at the main figures, but they sit on a raised platform that we look down upon. ■ The colors are rich and vibrant. ■ Extensive use of gold to indicate material richness and status of the figures. ■ Words written in Indian script. |

Using specific visual evidence, explain at least two techniques that Bichitr used that are part of Indian portrait tradition. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■ Work done in watercolor. ■ Figures seated in an Asian-style pose. ■ Main figures are sumptuously dressed indicating their wealth and position. ■ Great attention paid to richly illustrated fabrics. ■ Great attention paid to minute details, but not at the expense of the overall scene. |

Discuss how this work references works of art in the Western tradition. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■ Putti carry a canopy over the heads of the seated figures. ■ Putti have Western-style wings and wear Western-style crowns. |