Content Area: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: 1600–1700

The term “Baroque” means “irregularly shaped” or “odd,” a negative word that evolved in the eighteenth century to describe the Baroque’s departure from the Italian Renaissance.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Gaulli, Triumph of the Name of Jesus)

Essential Knowledge:

■Baroque art can be found in New Spain.

■Baroque art still has a basis on classical formulas, but also has an interest in dynamic compositions and theatricality.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Rubens, Henri IV Receives the Portrait of Marie de’ Medici)

Essential Knowledge:

■There are the beginnings of global commercial and artistic networks.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew)

Essential Knowledge:

■The period is dominated by an experimentation of visual elements, i.e., atmospheric perspective, a bold use of color, creative compositions, and an illusion of naturalism.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Le Vau and Hardouin-Mansart, Versailles)

Essential Knowledge:

■There is a more pronounced identity of the artist in society; the artist has more structured training opportunities.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance)

Essential Knowledge:

■Baroque art is studied in chronological order and by geographic region.

■There is a large body of primary source material housed in libraries and public institutions.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In 1600, the artistic center of Europe was Rome, particularly at the court of the popes. The completion of Saint Peter’s became a crusade for the Catholic Church, both as an evocation of faith and as a symbol of the Church on earth. By 1650, however, the increased power and influence of the French kings, first at Paris and then at their capital in Versailles, shifted the art world to France. While Rome still kept its allure as the keeper of the masterpieces for both the ancient world and the Renaissance, France became the center of modern art and innovation, a position it kept unchallenged until the beginning of World War II.

The most important political watershed of the seventeenth century was the Thirty Years’ War, which ended in 1648. Ostensibly started over religion, and featuring a Catholic resurgence called the Counter-Reformation, the Thirty Years’ War also had active political, economic, and social components as well. The war succeeded in devastating central Europe so effectively that economic activity and artistic production ground to a halt in this region for the balance of the seventeenth century.

The Counter-Reformation movement reaffirmed all the things the Protestant Reformation was against. Protestants were largely iconoclasts, breaking painted and sculpted images in churches; Catholics endorsed the place of images and were reinspired to create new ones. Protestants derided saints; Catholics reaffirmed the communion of saints and glorified their images. Protestants played down miracles; Catholics made them visible and palpable as in the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (Figures 17.4a and 17.4b).

Patronage and Artistic Life

Even with all the religious conflict, the Catholic Church was still the greatest source of artistic commissions in the seventeenth century, closely followed by royalty and their autocratic governments. Huge churches and massive palaces had big spaces that needed to be filled with large paintings commanding high prices. However, artists were not just interested in monetary gain; many Baroque artists such as Rubens and Bernini were intensely religious people, who were acting out of a firm commitment to their faith as well as to their art. Credit must be given to the highly cultivated and farsighted patrons who allowed artists to flourish; Pope Urban VIII, for example, sponsored some of Bernini’s best work.

BAROQUE ARCHITECTURE

Landscape architecture becomes an important artistic expression in the Baroque. Starting at Versailles (Figure 17.3e) and continuing throughout the eighteenth century, palaces are envisioned as the principal feature in an ensemble with gardens that are imaginatively arranged to enhance the buildings they framed. Long views are important. Key windows are viewing stations upon which gardens spread out before the viewer in an imaginatively orchestrated display that suggests man’s control over his environment. Views look down extended avenues carpeted by lawns and embraced by bordering trees, usually terminating in a statue or a fountain. The purpose is to impress the viewer with a sense of limitlessness.

Baroque architecture relies on movement. Façades undulate, creating symmetrical cavities of shadow alternating with projecting pilasters that capture the sun. Emphasis is on the center of the façade with wave-like forms that accentuate the entrance. Usually entrances are topped by pediments or tympana to reinforce their importance. A careful interplay of concave and convex shapes marks the most experimental buildings by Borromini. Interiors are richly designed to combine all the arts; painting and sculpture service the architectural members in a choreographed ensemble. The aim of Baroque buildings is a dramatically unified effect.

Baroque architecture is large; it seeks to impress with its size and its elaborate ornamentation. In this regard, the Baroque style represents the imperial or papal achievements of its patrons—proclaiming their power and wealth. Buildings are erected at high points accessible by elaborately carved staircases, ones that spill out toward the spectator and change direction—and view—as they rise.

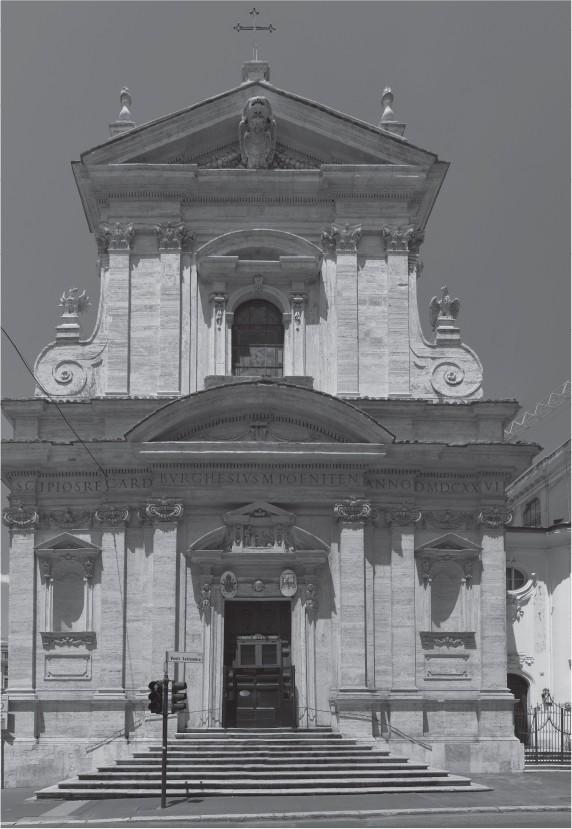

Carlo Maderno, Santa Maria della Vittoria, 1605–1620, Rome (Figure 17.1)

Figure 17.1: Carlo Maderno, Santa Maria della Vittoria, 1605–1620, Rome

Form

■First story: six Ionic pilasters; emphasis placed on center of façade.

■Round and triangular pediments; broken pediments; swags and scrollwork.

Function

■Catholic church, originally dedicated to Saint Paul.

Context

■Rededicated to the Virgin Mary in gratitude for a military victory in Bohemia in 1620.

■The Turkish standards captured in the Siege of Vienna in 1683 are on display.

■Single wide nave

■One of the side chapels houses Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (Figures 17.4a and 17.4b), with a window added to illuminate the sculptural group.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 89

Web Source http://romeartlover.it/Vasi148.htm

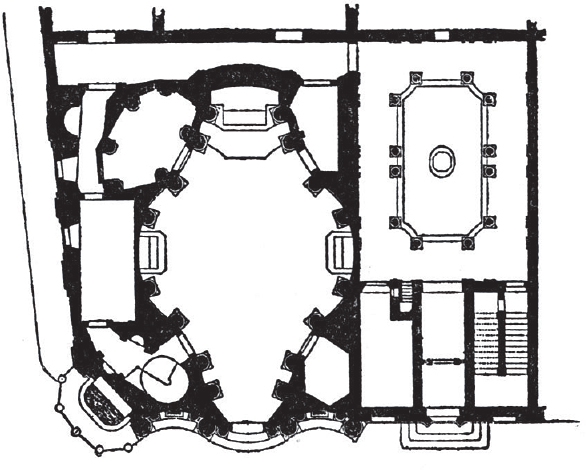

Francesco Borromini, Saint Charles of the Four Fountains (San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane), 1638–1646, stone and stucco, Rome (Figures 17.2a, 17.2b, and 17.2c)

Form

■So named because it is on a street intersection in Rome with four fountains.

Exterior

■Unusually small site.

Figures 17.2a: Francesco Borromini, Saint Charles of the Four Fountains (San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane), 1638–1646, stone and stucco, Rome

Figure 17.2b: Francesco Borromini, interior of Saint Charles of the Four Fountains (San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane), 1638–1646, stone and stucco, Rome

Figure 17.2c: Francesco Borromini, plan of Saint Charles of the Four Fountains (San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane)

■The building is designed with alternating convex and concave patterns and undulating volumes in both the ground plan and on the façade.

■The façade higher than the rest of the building.

Interior

■The interior side chapels merge into a central space.

■The interior dome is oval shaped and coffered.

■The dome has an interconnection of different shapes that fit together seamlessly; they illustrate the Baroque admiration for multiplicity that resolves into a unified space.

■The walls are treated sculpturally; Baroque drama and complexity.

■Borromini worked in shades of white, avoided colors used in many other Baroque buildings.

Function

■It was built as part of a complex of monastic buildings for the Spanish Trinitarians, an order of religious dedicated to freeing Christian slaves.

Context

■Sculptures of Trinitarian saints are placed on the façade.

■Medallion on façade once held a fresco of the Trinity.

■Borromini worked on the building for free, giving him more artistic license.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 88

Web Source https://vimeo.com/135904560

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Architectural Sculpture

–Temple of Amun-Re (Figures 3.8a, 3.8b, 3.8c)

–Parthenon (Figures 4.4, 4.16b)

–Lakshmana Temple (Figures 23.7a, 23.7b)

Figure 17.3a: Louis Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Versailles, begun 1669, masonry, stone, wood, iron, and gold leaf, Versailles, France

Figure 17.3b: Louis Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Versailles façade, begun 1669, masonry, stone, wood, iron, and gold leaf, Versailles, France

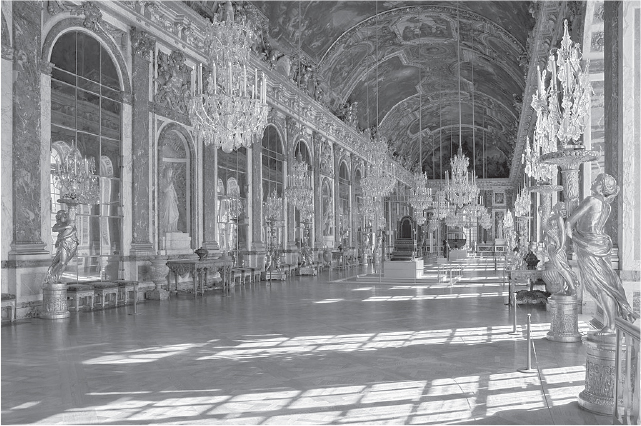

Louis Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Versailles, begun 1669, masonry, stone, wood, iron, and gold leaf; gardens, Versailles, France (Figures 17.3a–17.3e)

Figure 17.3c: Louis Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Versailles courtyard, begun 1669, masonry, stone, wood, iron, and gold leaf, Versailles, France

Figure 17.3d: Louis Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Versailles, Hall of Mirrors, begun 1669, masonry, stone, wood, iron, and gold leaf, sculpture: bronze and marble, Versailles, France

Figure 17.3e: Versailles gardens, begun 1669, Versailles, France

Function

■This is the palace of King Louis XIV and subsequent kings and their courts.

■The palace expresses the idea of the absolute monarch; the massive scale of the project is indicative of the massive power of the king.

Form and History

■Louis XIV reorganized and remodeled an existing hunting lodge into an elaborate palace.

■The center of the building is Louis XIV’s bedroom, or audience chamber, from which all aspects of the design radiate like rays from the sun (hence Louis’ sobriquet the Sun King).

■The building is centered in a vast garden and town complex that radiated from it.

■There is a subdued exterior decoration on the façade; the undulation of projecting members is understated.

Hall of Mirrors

■240 feet long, facing the garden façade.

■Barrel-vaulted painted ceiling (paintings stress the military victories of Louis XIV; rooms that flank the Hall of Mirrors are thematically related, one of Peace and the other War).

■Light comes in from one side and ricochets off large panes of glass, the largest that could be made at the time.

■This is an example of a use of flickering light in an architectural setting.

■Mirrors were among the most expensive items manufactured in the seventeenth century—the Hall of Mirrors is an extravagant display of wealth.

■Mirrors were made exclusively in Venice at the time; workers had to be imported from Venice to make the mirrors, which conformed to the dictates that the decorations at Versailles had to be made in France.

■Hall of Mirrors used for court and state functions: embassies, births, and marriages were celebrated in this room.

■Subsequent history:

–Used by Bismarck to declare William I as German emperor after the defeat of the French in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

–Used reciprocally by the French after the defeat of the Germans in World War I to sign the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Gardens

■Classically and harmoniously arranged.

■Formal gardens near the palace; more wooded and less elaborate plantings farther from the palace.

■Baroque characteristics:

–Large size.

–Long vistas.

–Terminal views in fountains and statuary.

–Geometric plantings show control of nature.

■A mile-long canal crossed by another canal forms the main axis of the gardens; linked to the rising sun over the palace.

■Only the fountains near the palace were turned on all the time; others were turned on only when the king progressed through the gardens.

■Illustrates the belief that humans can organize and control nature to make a more refined experience.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 93

Web Source http://en.chateauversailles.fr/homepage

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: National Capitals

–Nan Madol (Figures 28.1a, 28.1b)

–Great Zimbabwe (Figures 27.1a, 27.1b)

–Forbidden City (Figures 24.2a, 24.2b, 24.2c, 24.2d)

BAROQUE PAINTING AND SCULPTURE

Baroque artists explored subjects born in the Renaissance but previously considered too humble for serious painters to indulge in. These subjects, still life, genre, and landscape painting, flourished in the seventeenth century as never before. While religious and historical paintings were still considered the highest form of expression, even great artists such as Rembrandt and Rubens painted landscapes and genre scenes. Still lifes were a specialty of the Dutch school.

Landscapes and still lifes exist not in and of themselves, but to express a higher meaning. Still lifes frequently contain a vanitas theme, which stresses the brevity of life and the folly of human vanity. Broad open landscapes feature small figures in the foreground acting out a Biblical or mythological passage. Genre paintings often had an allegorical commentary on a contemporary or historical issue.

Landscapes were never actual views of a particular site; instead they were composed in a studio from sketches done in the field. The artist was free to select trees from one place and put them with buildings from another. Landscape painters felt they had to reach beyond the visual into a world of creation that relies on the thoughtful combination of disparate elements to make an artistic statement.

Painters were fascinated by Caravaggio’s use of tenebrism—even the greatest painters of the century experimented with it. The handling of light and shadow became a trademark of the Baroque, not only for painters, but for sculptors and architects as well. Northern artists specialized in impasto brushwork, which created a feeling of spontaneity with a vibrant use of visible brushwork. Similarly, sculptors animated the texture of surfaces by variously polishing or abrading surfaces.

Painters like Caravaggio painted with an expressive sense of movement. Figures are dramatically rendered, even in what would appear to be a simple portrait. Light effects are key, as offstage sources illuminated parts of figures in a strong dark light contrast called tenebroso. Colors are descriptive and evocative. Inspiration comes from the Venetian Renaissance, and passes through Caravaggio and onto Rubens and his followers, who are called Rubénistes. Naturalists reject what they perceive as the contortions and artificiality of the Mannerists.

As in the other arts, Baroque sculpture stressed movement. Figures are caught in mid-motion, mouths open, with the flesh of one figure yielding to the touch of another. Some large works, particularly those by Bernini, were often meant to be placed in the middle of the floor or at a slight distance from a wall and be seen in the round. Sculptors employ negative space, carving large openings in a work so that the viewer can contemplate a multiplicity of angles. Marble is treated with a tactile sense: human skin given a high polish, angel wings shown with a feathery touch, animal skins reveal a coarser feel. Baroque sculptors found inspiration in the major works of the Greek Hellenistic period.

Italian Baroque Art

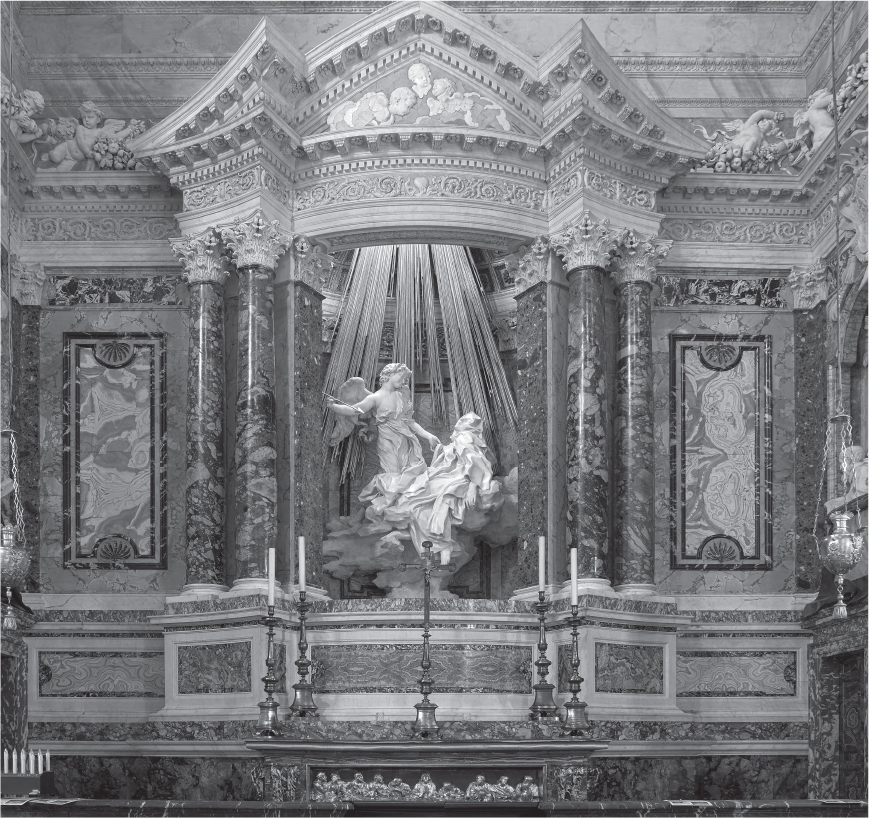

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–1652, marble, stucco and gilt bronze, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome (Figures 17.4a and 17.4b)

Figure 17.4a: Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Cornaro Chapel, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–1652, marble, stucco, and gilt bronze, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

Figure 17.4b: Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–1652, marble, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

Form

■Marble is handled in a tactile way to reveal textures: skin is high gloss, feathers of angel are rougher, drapery is animated and fluid, clouds are roughly cut.

■Figures seem to float in space; the rays of God’s light symbolically illuminate the scene from behind.

■Natural light is redirected onto the sculpture from a window hidden above the work.

■The work captures a moment in time—a characteristic of Baroque art.

Patronage

■Stage-like setting with the patrons, members of the Cornaro family, sitting in theater boxes looking on and commenting.

Function and Context

■Saint Teresa was canonized in 1622; a new saint at the time.

■This is a sculptural interpretation of Saint Teresa’s diary writings, in which she tells of her visions of God, many involving an angel descending with an arrow and plunging it into her.

■Saint Teresa’s pose suggests sexual exhaustion, a feeling that is consistent with her description of spiritual ecstasy in her diary entries.

■This is a Counter-Reformation work that illustrates the use of images to increase piety and devotion among the Catholic faithful.

■It is located inside Santa Maria della Vittoria (Figure 17.1).

■Cf. Visionary experience depicted in Lintel 25, Yaxchilán (Figure 26.2).

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 89

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Use of Light and Dark

–Lanzón Stone (Figure 26.1b)

–Court of the Lions (Figure 9.15b)

–Pantheon (Figures 6.11a, 6.11b)

Caravaggio, Calling of Saint Matthew, 1597–1601, oil on canvas, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome (Figure 17.5)

Figure 17.5: Caravaggio, Calling of Saint Matthew, 1597–1601, oil on canvas, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Function and Patronage

■One of three paintings illustrating the life of Saint Matthew in a chapel dedicated to him by the Contarelli family.

Form

■Diagonal shaft of light points directly to Saint Matthew, who points to himself as if unsure that Christ would select him.

■Light coming in from two sources on the right creates a tenebroso effect on the figures.

■Christ’s pose is the inverse of Adam’s on the Sistine Ceiling.

■Only a slight suggestion of a halo on Christ’s head indicates sanctity of the scene.

■Foppishly dressed figures wear cutting-edge Baroque fashion.

■Figures placed on a shallow stage.

■Sensual figures, everyday people.

■Naturalist approach to the Baroque.

Context

■Matthew was a tax collector; hence he is seated at a table with coins being counted.

■Story taken from Matthew 9:9: “As Jesus went on from there, he saw a man named Matthew sitting at the tax collector’s booth. ‘Follow me,’ he told him, and Matthew got up and followed him.”

■Two figures on the left are so concerned with counting the money they do not even notice Christ’s arrival; symbolically their inattention (and by implication, everyone else’s) to Christ deprives them of the opportunity he offers: eternal life.

■Jesuit influence on Counter-Reformation Baroque art; the sensual or physical expression of faith as expressed in Saint Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 85

Web Source https://www.artble.com/artists/caravaggio/paintings/the_calling_of_saint_matthew

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Light Effects

–Viola, The Crossing (Figures 29.18a, 29.18b)

–Walker, Darkytown Rebellion (Figure 29.21)

–Notre Dame de la Belle Verriere (Figure 12.8)

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Triumph of the Name of Jesus, 1676–1679, fresco and stucco, Il Gesù, Rome (Figure 17.6)

Figure 17.6: Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Triumph of the Name of Jesus, 1676–1679, fresco and stucco, Il Gesù, Rome

Form and Content

■On the ceiling in the main nave of Il Gesù, Rome (Figure 16.6).

■In the center is the monogram of Jesus, IHS, in a brilliant sea of golden color.

■Figures tumble below the name; some are carved in stucco and enhance the three-dimensional effect.

■Some cast long shadows across the barrel vault.

■Some painted figures are not stucco, but maintain a vibrant three-dimensional illusion.

■It is as if the ceiling were opened to the sky and the figures are spiraling around Jesus’s name.

■Depicted in the center are holy men and women.

■Around the rim are priests, soldiers, noblemen, and the Magi.

■Allegories of avarice, simony, heresy, and vanity occupy the lowest registers.

■Di sotto in sù.

Function

■A Last Judgment scene, placed over the barrel vault of the nave; cf. Last Judgment scenes placed on the walls of chapels (Sistine Chapel: Figure 16.2e; Arena Chapel: Figure 13.1b).

■Message to the faithful: the damned are cast into hell; the saved rise heavenward.

Context

■Inspired by Saint Paul’s epistle to the Philippians 2:10: “That at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth.”

■There is the influence of Bernini’s dramatic emotionalism in the style; Gaulli was Bernini’s pupil.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 82

Web Source http://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/45004

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ceiling Paintings

–Michelangelo, The Flood (Figure 16.2d)

–Catacomb of Priscilla Good Shepherd (Figure 7.1c)

–Lascaux Caves (Figure 1.8)

Spanish Baroque Art

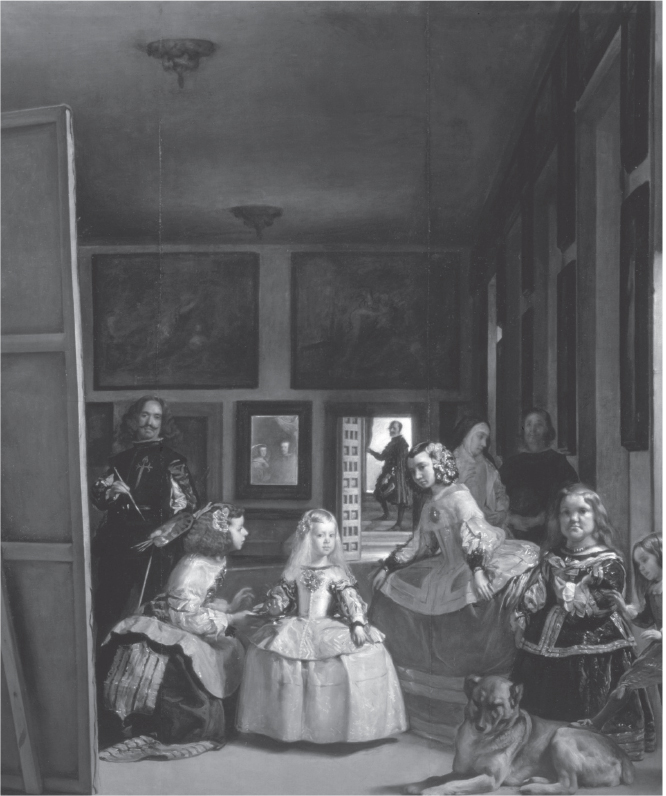

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656, oil on canvas, Prado, Madrid (Figure 17.7)

Figure 17.7: Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656, oil on canvas, Prado, Madrid

Content

■Portrait of the artist in his studio at work; he steps back from his very large canvas and looks at the viewer.

■Central is the Infanta Margharita of Spain with her meninas (attendants), a dog, a dwarf, and a midget. Behind are two chaperones in half-shadow. In the doorway is perhaps José Nieto, who was head of the queen’s tapestry works (hence his hand on a curtain).

■The king and queen appear in a mirror. But what is the mirror reflecting?

–Velázquez’s canvas?

–The king and queen perhaps standing in the viewer’s space—is this why people have turned around?

–Or is it reflecting a painting of the king and queen on the far wall of the room?

■What is the painter painting?

–The royal family?

–The Infanta?

–A painting of this painting?

–Us?

–Ultimately, there is no answer, which expresses the Baroque fascination with exploring reality.

Form

■Alternating darks and lights draw the viewer deeper into the canvas; the mirror simultaneously reflects out into the viewer’s space.

■Dappled effect of light on shimmering surfaces.

■Painterly brushstrokes seen in the sleeves of the Infanta and the hands of the artist.

Function

■Painting originally hung in King Philip IV’s study.

Context

■Velázquez wears the cross of the Royal Order of Santiago, which elevated him to knighthood; this work seeks to establish painting as a noble occupation.

■Paintings on the back wall depict Minerva, goddess of wisdom and patroness of the arts.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 91

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Self-Portraits

–Mori, Pure Land (Figure 29.19)

–Raphael, School of Athens (Figure 16.3)

–Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings (Figure 23.9)

Flemish Baroque Art

Peter Paul Rubens, Marie de’ Medici Cycle, 1621–1625, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris (Figure 17.8)

Figure 17.8: Peter Paul Rubens, Henri IV Receives the Portrait of Marie de’ Medici, 1621–1625, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris

Form

■Heroic gestures, demonstrative spiraling figures.

■Mellow intensity of color, inspired by Titian and Caravaggio.

■Sumptuous full-fleshed women.

■Splendid costumes suggest an opulent theatrical production.

■Allegories assist in telling the story and mix freely with historical people.

Function and Context

■24 huge historical paintings allegorically retelling the life of Marie de’ Medici, queen of France, wife of King Henry IV; the series also contains three portraits.

■Commissioned by Marie de’ Medici, at the time the widow of Henry IV.

■The series was placed in Marie de’ Medici’s home in Paris, the Luxembourg Palace.

Henri IV Receives the Portrait of Marie de’ Medici

■Henry IV is smitten by the portrait of his intended; the portrait is the center of a swirling composition.

■The portrait is held by Cupid (the god of love) and Hymen (the god of marriage).

■Mythological gods Jupiter (symbolized by an eagle) and Juno (symbolized by a peacock) look down from below; they are symbolic of marital harmony. They express their support.

■Royalty was considered demigods; the approval of mythological gods is in concert with their beliefs about themselves.

■This represents the tradition of portraits being exchanged before the marriage.

■They were actually married by proxy in 1600.

■Behind Henry is the personification of France:

–France is a female figure with a masculine helmet and manly legs.

–She whispers to Henry to choose love over war.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 86

Web Source https://fds.duke.edu/db/attachment/2652

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Relationships

–Klimt, The Kiss (Figure 21.12)

–Veranda post (Figure 27.14)

–Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and three daughters (Figure 3.10)

Dutch Baroque Art

While the Baroque is often associated with stately court art, it also flourished in mercantile Holland. Dutch paintings are harbingers of modern taste: landscapes, portraits, and genre paintings flourished; religious ecstasies, great myths, and historical subjects were avoided. In contrast to the massive buildings in other countries, Dutch houses are small and wall space scarce, so painters designed their works to hang in more intimate settings. Even though commerce and trade boomed, the Dutch did not want industry portrayed in their works. Ships are sailboats, not merchant vessels, which courageously braved the weather, not unloaded cargo. Animals are shown quietly grazing rather than giving milk or being shorn for wool. A featureless flat Dutch landscape is animated by powerful and evocative skies.

Dutch painting, however, has several things in common with the rest of European art. Most significantly, Dutch art features many layers of symbolism that provokes the viewer to intellectual consideration. Still life paintings, for example, are not the mere arrangement of inanimate objects, but a cause to ponder the fleeting nature of life. Stark church interiors often symbolized the triumph of Protestantism over Catholicism. Indeed, while Dutch art may seem outside the mainstream of the Baroque, it does have important parallels with contemporary art in the rest of Europe.

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait with Saskia, 1636, etching, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (Figure 17.9)

Figure 17.9: Rembrandt, Self-Portrait with Saskia, 1636, etching, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

Content

■Rembrandt is seen drawing or perhaps making an etching.

■Saskia is seated deeper into the work, but is very noticeable because she is portrayed with a lighter touch.

Function

■Not for general sale but for private purposes.

Context

■The scene depicts the 30-year-old Rembrandt with his new bride.

■This is the only image of Rembrandt with his wife together in an etching.

■Images of Saskia are abundant in Rembrandt’s output; she was a source of inspiration for him.

■Marital harmony; Saskia as a muse who inspires him.

■Characteristic of Rembrandt: they are wearing fanciful, not contemporary, dress.

■Saskia was the mother of four.

■Rembrandt’s self-portraits included 50 paintings, 32 etchings, and 7 drawings.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 87

Web Source http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/58483

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Graphic Arts

–Dürer, Adam and Eve (Figure 14.3)

–Cranach, Allegory of Law and Grace (Figure 14.5)

–Kollwitz, Memorial Sheet for Karl Liebknecht (Figure 22.4)

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Figure 17.10)

Figure 17.10: Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Form and Content

■Light enters from the left, illuminating the figures and warmly highlighting textures and surfaces: the woman’s garments, wooden table, marble checkerboard floor, jewelry, the painting, etc.

■A moment in time: stillness and timelessness.

■The woman is dressed in fine, fur-trimmed clothing.

■Geometric lines focus on a central point at the pivot of the balance.

■The figure seems unaware of the viewer’s presence.

■Her pensive stillness suggests she may be weighing something more profound than jewelry.

Context

■A small number of Vermeer works are in existence.

■Except for two landscapes, Vermeer’s works portray intimate scenes in the interior of Dutch homes.

■The viewer looks into a private world in which seemingly small gestures take on a significance greater than what first appears.

■A family member may have posed for the painting, perhaps Vermeer’s wife, Caterina.

Theories

■Is it a genre scene or an allegory? Or both?

■A moment of weighing and judging.

■In the background is a painting of the Last Judgment, a time of weighing souls:

–The woman is at a midpoint between earthly jewels and spiritual goals such as meditation and temperance.

–The balance (scale) has nothing in it; pearls and coins on the table waiting to be measured; may be symbolic of a balanced state of mind.

–The balancing reference perhaps relates to the unborn child.

–This is Catholic subject matter in a Protestant country; Vermeer and his family were Catholic.

■Vanitas painting: gold should not be a false allure.

■Vermeer may have used a camera obscura.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 92

Web Source http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Collection/art-object-page.1236.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Genre Scenes

–Grave stele of Hegeso (Figure 4.7)

–Cassatt, The Coiffure (Figure 21.7)

– Bayeux Tapestry, First Meal (Figure 11.7b)

Rachel Ruysch, Fruit and Insects, 1711, oil on wood, Uffizi, Florence (Figure 17.11)

Form

■Asymmetrical, artful arrangement.

■A finely detailed illustration of natural objects in a rural setting.

Content

■Not a depiction of actual flowers, but a construct of perfect specimens all in bloom at the same time.

■The artist probably used illustrations in botany textbooks as a basis for the painting.

■Wheat and grapes juxtaposed: may have been a reference to the Eucharist.

Figure 17.11: Rachel Ruysch, Fruit and Insects, 1711, oil on wood, Uffizi, Florence

Context

■The artist’s father was a professor of anatomy and botany as well as an amateur painter.

■The artist produced a number of such still lifes in woodland settings.

■Parallels Dutch interest in botany, and the growing of flowers for decorative and medicinal purposes.

■Flowers were symbols of wealth and status.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 96

Web Source https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rachel-Ruysch

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Still Lifes

– Daguerre, Still Life in Studio (Figure 20.8)

– Matisse, Goldfish (Figure 22.1)

VOCABULARY

Di sotto in sù: (“from the bottom up”) a type of ceiling painting in which the figures seem to be hovering above the viewers, often looking down at us (Figure 17.6).

Genre painting: painting in which scenes of everyday life are depicted

Impasto: a thick and very visible application of paint on a painting surface

Still life: a painting of a grouping of inanimate objects, such as flowers or fruit (Figure 17.11)

Tenebroso/Tenebrism: a dramatic dark and light contrast in a painting (Figure 17.5)

Vanitas: a theme in still life painting that stresses the brevity of life and the folly of human vanity (Figure 17.11)

SUMMARY

The Baroque has always symbolized the grand, the majestic, the colorful, and the sumptuous in European art. While the work of Rubens and Bernini and the architecture of Versailles certainly qualify as this view of the Baroque, the period is equally famous for small Dutch paintings of penetrating psychological intensity and masterful interplays of light and shadow.

Illusion is a key element of the Baroque aesthetic. Whether it be the floating of Saint Teresa on a cloud or the trompe l’oeil ceilings of Roman palaces, the Baroque teases our imagination by stretching the limits of the space deep into the picture plane. The same complexity of thought is applied to intriguing and symbolic still lifes, known as vanitas paintings, or intricate groupings of figures such as Las Meninas (Figure 17.7).

The Baroque is characterized by a sense of ceaseless movement. Building façades undulate, sculptures are seen in the round, and portraits show sitters ready to speak or interact with the viewer. Naturalist painters, like Caravaggio, use dramatic contrasts of light and dark to highlight the movement of the figures.

The Baroque achieves a splendor through an energetic interaction reminiscent of Hellenistic Greek art, which serves as its original role model.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.The theatrical illusionism of Baroque works is similar to those seen in which of the following periods?

(A)Roman Republic

(B)Chinese Ming

(C)Cambodian Khmer

(D)Greek Hellenistic

2.Vanitas paintings are usually seen as symbolic elements in

(A)still lifes, where they demonstrate the passing nature of human life

(B)genre paintings, where they show the folly of human interactions

(C)landscapes, where they stress the changing nature of the seasons

(D)historical paintings, where they indicate the folly of greatness and triumph

3.An innovation seen in the architecture of Francesco Borromini is his

(A)use of non-Western elements in his Catholic churches

(B)massing of forms on a grand scale to achieve a powerful effect

(C)use of gardens to enhance the setting of his buildings

(D)creation of stone buildings that are not linear but curvilinear and undulating in form

4.Which of the following is the prime reason why Caravaggio’s public and patrons found his art objectionable?

(A)He copied directly from great masters of the Renaissance and was considered derivative rather than inventive.

(B)He worked for discredited bishops, popes, and kings and was tainted by association.

(C)He made saintly figures have earthly characteristics, which shocked church officials.

(D)He showed the harsh glare of direct sunlight on his figures, which illuminated them in an uncompromising light.

5.The union of mythological gods and allegorical figures with real people as seen in the Peter Paul Rubens painting Henri IV Receives the Portrait of Marie de’ Medici from the Marie de’ Medici Cycle can also be seen in

(A)Reliquary of Sainte-Foy

(B)Code of Hammurabi

(C)Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace

(D)Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais

Short Essay

Practice Question 6: Continuity and Change

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

This work is Woman Holding a Balance by Johannes Vermeer from 1664.

In this painting, Jan Vermeer is influenced by contemporary trends that are characteristic of Dutch painting in seventeenth-century Holland.

Describe specific characteristics of Dutch painting seen in this work.

Using at least two specific details, discuss the symbolic elements that could lead to an allegorical interpretation of this work.

Using at least two specific contextual details, discuss how this work reflects seventeenth-century Dutch society.

ANSWER KEY

1.D

2.A

3.D

4.C

5.B

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(D) Works like the Winged Victory of Samothrace show a theatrical illusionism, similar to that of Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa.

2.(A) Vanitas paintings are still lifes, generally still lifes that stand alone, although they can be part of larger compositions. They usually have symbols of the passing of time, like clocks, skulls, or hourglasses, which symbolize—among other things—the folly of human endeavor.

3.(D) Borromini’s buildings, like San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, show his interest in cutting stone into undulating and curvilinear forms.

4.(C) Caravaggio was famous for using models who were not glorious or saintly looking for images of angels, the Virgin Mary, and various saints.

5.(B) In the Code of Hammurabi, the god Shamash has contact with Hammurabi by literally handing him the code.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Describe specific characteristics of Dutch painting seen in this work. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■It is not grand, large, or overwhelming but small and concentrated. ■It does not have historical associations. ■It is seemingly simple but asks the viewer to contemplate its meaning. ■It is not theatrical but poignant. ■The meaning is captured in a simple gesture and a moment suspended in time. ■Genre scene. ■Mercantile activity seen in a symbolic setting. |

Using at least two specific details, discuss the symbolic elements that could lead to an allegorical interpretation of this work. |

1 point for each symbolic element |

Answers could include: ■Weighing and judging. ■Holds a balance or scales. ■Pregnant woman. ■Vanitas theme. ■Symbolism of various objects. ■Last Judgment in the painting in the background. |

Using at least two specific contextual details, discuss how this work reflects seventeenth-century Dutch society. |

1 point for each element of context |

Answers could include: ■Merchant activity of weighing goods. ■Christian imagery of the judging and weighing of souls. ■Deeper meaning seen in common activities of the time. ■Lack of ostentation in dress, home, and environment reflects Dutch pragmatism. ■Genre scenes can carry a higher meaning. ■Lack of symbols of royalty or historical allusions; an anti-Spanish feeling. |