Content Area: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 C.E.

Renaissance in Northern Europe

TIME PERIOD: 1400–1600

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Cranach, Allegory of Law and Grace)

Essential Knowledge:

■Renaissance art is generally the art of Western Europe.

■Renaissance art is influenced by a number of concerns, including the art of the classical world, Christianity, a greater respect for naturalism, and formal artistic training.

■The Reformation and the Counter-Reformation created a division in European art between the northern artists who were generally Protestant and the southern artists who were generally Catholic. In the north, religious art was deemphasized and still life, genre, landscape, and portraiture increased in popularity. In the south, religious art continued to be important, in addition to an emphasis on naturalism, dynamic compositions, and pageantry.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Dürer, Adam and Eve)

Essential Knowledge:

■There are the beginnings of global commercial and artistic networks.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Cranach, Allegory of Law and Grace)

Essential Knowledge:

■The period is dominated by an experimentation of visual elements, i.e., atmospheric perspective, a bold use of color, creative compositions, and an illusion of naturalism.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait)

Essential Knowledge:

■There is a more pronounced identity of the artist in society; the artist has more structured training opportunities.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait)

Essential Knowledge:

■Renaissance art is studied in chronological order.

■There is a large body of primary source material housed in libraries and public institutions.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The prosperous commercial and mercantile interests in the affluent trading towns of Flanders stimulated interest in the arts. Emerging capitalism was visible everywhere, from the first stock exchange established in Antwerp in 1460 to the marketing and trading of works of art. Cities vied with one another for the most sumptuously designed cathedrals, town halls, and altarpieces—in short, the best Europe had to offer.

Political and religious turmoil began with the Reformation, which is traditionally dated to 1517 when a German monk and scholar named Martin Luther nailed a list of his complaints to the doors of All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Germany. Perhaps unknowingly, he began one of the greatest upheavals in European history, causing a split in the Christian faith and political turmoil that would last for centuries. Those countries that were Christian the shortest period of time (Germany, Scandinavia, and the Netherlands) became Protestant. Those with longer Christian traditions (Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Poland) remained Catholic.

With a Protestant wave of anti-Catholic feeling came an iconoclastic movement attacking paintings and sculptures of holy figures, which only a short while before were considered sacred. Calvinists, in particular, were staunchly opposed to what they saw as blasphemous and idolatrous images; they spearheaded the iconoclastic movement.

Patronage and Artistic Life

The conflict between Protestant iconoclasm and Catholic images put artists squarely in the middle. On the one hand, the Church was an excellent source of employment; on the other, what if the contentions of the Protestants were true?

Many, like Dürer, tried to resolve the issue by either turning to other types of painting, like portraits, or by seeking a middle road by playing down religious ecstasies or the lives of the saints. Protestants thought that God could be reached directly through human intercession, so paintings of Jesus, when permitted, were direct and forceful. Catholics wanted intermediaries, such as Mary, the saints, or the priesthood to direct their thoughts, so those images were more permissible to them. However, Catholics always insisted that a sculpture of Mary was just a reminder of the figure one was praying to. Idolatry was not endorsed.

The Northern European economy can be characterized by a capitalist market system that flourished due to expansive trade across the Atlantic. This brought with it a parallel emphasis on buying and selling works of art as commodities. New technologies in printmaking made artists internationally popular, and more courted than ever before.

NORTHERN RENAISSANCE PAINTING

One of the most important inventions in the last thousand years, if not history, is the development of movable type by Johann Gutenberg. The impact was enormous. This device could mass produce books, make them available to almost anyone, and have them circulated on a wide scale.

However, mechanically printed books looked cheap and artificial to those who were used to having their books handmade over the course of years, as the Golden Haggadah (Figure 12.10a) did for the super-wealthy patrons. Gutenberg’s first book, the Bible, was printed mechanically, but the decorative flourishes—mostly initial letters before each chapter—were hand painted by calligraphers. Meanwhile, a similar mechanical process gave birth to the print, first as a woodcut, then as an engraving, and later as an etching. Prints were mass produced and relatively inexpensive, since the artist made a prototype that was reprinted many times. Although each print was individually cheaper than a painting, the artist made his profit on the number of reproductions. Indeed, fame could spread more quickly with prints, because these products went everywhere, whereas paintings were in the hands of single owners.

The second important development in the fifteenth century was the widespread use of oil paint. Prior to this, wall paintings were done in fresco and panel paintings in tempera. Oil paint was developed as an alternative in a part of Europe in which fresco was never that popular.

Oil paint produces exceptionally rich colors, having the notable ability to accurately imitate natural hues and tones. It can generate enamel-like surfaces and sharp details. It also preserves well in wet climates, retaining its luster for a long time. Unlike tempera and fresco, oil paint is not quick drying and requires time to set properly, thereby allowing artists to make changes onto what they previously painted. With all these advantages, oil paint has emerged as the medium of choice for most artists since its development in Flanders in the Early Renaissance.

The great painted altarpieces of medieval art were the pride of accomplished painters whose works were on public view in the most conspicuous locations. Italian altarpieces from the age of Giotto tend to be flat paintings that stand directly behind an altar, often with gabled tops.

Alternatively, Northern European altarpieces are often cupboards rather than screens, with wings that open and close, folding neatly into one another. The large central scene is the most important, sometimes carved rather than painted; sculpture was considered a higher art form. Small paintings such as the Annunciation Triptych of 1425–1428 (Figure 14.1) were designed for portability. Larger works were meant to be housed in an elaborate Gothic frame that enclosed the main scenes. Sometimes the frame alluded to the architecture of the building in which the painting resided.

Altarpieces usually have a scene painted on the outside, visible during the week. On Sundays, during key services, the interior of the altarpiece is exposed to view. Particularly elaborate altarpieces may have had a third view for holidays.

Northern European artists were heavily influenced by International Gothic Painting, a courtly elegant art form, begun by Italian artists such as Simone Martini in the fourteenth century. This style of painting features thin, graceful figures that usually have an S-shaped curve as does Late Gothic sculpture. Natural details abound in small bits of reality that are carefully rendered. Costumes are splendidly depicted with the latest fashions and most stylish fabrics. Gold is used in abundance to indicate the wealth of the figures and the patrons who sponsored these works. Architecture is carefully rendered, frequently with the walls of buildings opened up so that the viewer can look into the interior. International Gothic paintings often have elaborate frames that match the sumptuous painting style.

Regardless of whether artists worked in the International Gothic tradition, Northern European painters generally continued the practice of opening up wall spaces to see into rooms as in the Annunciation Triptych (Figure 14.1). Typically, figures are encased in the rooms they occupy, rather than being proportional to their surroundings. Ground lines tilt up dramatically, as do table tops and virtually any flat surface. High horizons are the norm. Although symbolism can be seen in virtually any work of art in any art historical period, it seems to be particularly a part of the fabric of Northern European painting. Items that appear casually placed as a bit of naturalism can be construed as part of a symbolic network of interpretations existing on several important levels. Scholars have spilled a great deal of ink in decoding possible readings of important works.

Northern European art during the sixteenth century is characterized by the assimilation of Italian Renaissance ideas into a Northern European context. Michelangelo was enormously popular in Northern Europe, even though he never went there, and only one of his works did. However, many other Italian artists made the journey, including the elderly Leonardo da Vinci.

Northern European painting had a fondness for nature unknown in Italian art—whether it is seen in sweeping Alpine landscape views or the study of a rabbit or even a clump of earth. Landscapes, no matter how purely represented, generally have a trace of human involvement, sometimes shown by the presence of buildings or farms, or the rendering of small people in an overwhelming setting.

Northern artists continued to use high horizon lines that enabled a large area of the work to be filled with earthbound details. In general, there is a reluctance to use linear perspective in paintings, although atmospheric perspective is featured in landscapes.

Robert Campin workshop, Annunciation Triptych (also called Merode Altarpiece), 1427–1432, oil on wood, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Figure 14.1)

Figure 14.1: Robert Campin workshop, Annunciation Triptych (also called Merode Altarpiece), 1425–1428, oil on wood, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

■Triptych, or three-paneled altarpiece.

■Meticulous handling of paint; intricate details are rendered through the use of oil paint.

■Steep rising of the ground line; figures too large for the architectural space they occupy.

Function

■Meant to be in a private home for personal devotion.

Technique

■Oil paint gives the surface a luminosity and shine.

■Oil allows for layers of glazes that render soft shadows.

■Oil can also be erased with turpentine, allowing for changes and corrections.

Content

■Left panel: donors, middle-class people kneeling before the holy scene.

–Messenger appears at the gate to an enclosed garden.

■Center panel: Annunciation taking place in an everyday Flemish interior.

–Symbolism

•Towels and water represent Mary’s purity; water is a baptism symbol.

•Flowers have three buds, symbolizing the Trinity; the unopened bud represents the unborn Jesus.

•Mary is seated on a kneeler near the floor, symbolizing her humility.

•Mary blocks the fireplace, the entrance to hell.

•The candlestick symbolizes Mary holding Christ in the womb.

•The Holy Spirit with a cross comes in through the window, symbolizing the divine birth.

– Humanization of traditional themes: no halos, domestic interiors, view into a Flemish cityscape.

■Right panel: Joseph is working in his carpentry workshop; the mousetraps on the windowsill and the workbench symbolize the capturing of the devil.

–The mousetraps on the bench and in the shop window opening onto the street are thought to allude to references in the writings of Saint Augustine identifying the cross as the devil’s mousetrap.

Context

■Unusually, the main panel was not commissioned.

■Wings were commissioned when the main panel was purchased; the donor portrait was added at this time.

■After the donor’s marriage in the 1430s, the wife and messenger were added, which accounts for the rather squeezed-in look of the donor’s wife.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 66

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/470304

■Cross-Cultural Connections: Images of the Virgin Mary

–González, Virgin of Guadalupe (Figure 18.4)

–Lippi, Madonna and Child with Two Angels (Figure 15.3)

–Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (Figure 8.8)

Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, oil on wood, National Gallery, London (Figure 14.2)

Figure 14.2: Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, oil on wood, National Gallery, London

Form

■Meticulous handling of oil paint; great concentration of minute details.

■Linear perspective, but upturned ground plane and two horizon lines unlike contemporary Italian Renaissance art.

■Great care is taken in rendering elements of a contemporary Flemish bedroom.

Theories

■Traditionally assumed to be the wedding portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife.

■It may be a memorial to a dead wife, who could have died in childbirth.

■It may represent a betrothal.

■Arnolfini may be conferring legal and business privileges on his wife during an absence.

■The painting may have been meant as a gift for the Arnolfini family in Italy. It had the purpose of showing the prosperity and wealth of the couple depicted.

Context

■Symbolism of weddings:

–The custom of burning a candle on the first night of a wedding.

–Shoes are cast off, indicating that the couple is standing on holy ground.

–The groom is in a promising pose.

–The dog symbolizes fidelity.

■Two witnesses in the convex mirror; perhaps the artist himself, since the inscription reads “Jan van Eyck was here 1434.”

■The woman pulls up her dress to symbolize childbirth, although most likely she is not pregnant; the gesture may simply be a fashion of the time.

■Statue of Saint Margaret, patron saint of childbirth, appears on the bedpost.

■The man is standing near the window, symbolizing his role as someone who makes his way in the outside world; the woman appears further in the room to emphasize her role as a homemaker.

■Wealth is displayed in the opulent furnishings, the elaborate clothing, and the importing of fresh oranges from southern Europe.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 68

Web Source http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jan-van-eyck-the-arnolfini-portrait

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Couples in Art

–King Menkaura and queen (Figure 3.7)

–Veranda post (Figure 27.14)

–Justinian Panel and Theodora Panel (Figures 8.5 and 8.6)

Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1504, engraving, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Figure 14.3)

Figure 14.3: Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1504, engraving, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

■Influenced by classical sculpture; Adam looks like the Apollo Belvedere, and Eve looks like Medici Venus.

■Italian massing of forms, which he learned from his Italian trips.

■Ideal image of humans before the Fall of Man (Genesis 3).

■Contrapposto of figures from the Italian Renaissance, in turn also based on classical Greek art.

■Northern European devotion to detail.

Content

■Four humors are represented in the animals: cat (choleric, or angry), rabbit (sanguine, or energetic), elk (melancholic, or sad), ox (phlegmatic, or lethargic); the four humors were kept in balance before the Fall of Man; the humors fell out of balance after the successful temptation of the serpent.

■The mouse represents Satan.

■The parrot is a symbol of cleverness.

■Adam tries to dissuade Eve; he grasps the mountain ash, a tree from which snakes recoil.

Context

■Prominent placement of the artist’s signature indicates the rising status of his occupation.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 74

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/19.73.1/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: The Human Figure

–Polykleitos, Spear Bearer (Figure 4.3)

–Botticelli, Birth of Venus (Figure 15.4)

–Braque, The Portuguese (Figure 22.6)

Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim altarpiece, 1512–1516, oil on wood, Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar (Figures 14.4a and 14.4b)

Figure 14.4a: Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim altarpiece, first view, 1512–1516, oil on wood, Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar

Figure 14.4b: Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim altarpiece, second view, 1512–1516, oil on wood, Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar

Context

■Placed in a monastery hospital where people were treated for Saint Anthony’s fire, or ergotism—a disease caused by ingesting a fungus that grows on rye flour.

■The name of the disease explains the presence of Saint Anthony in the first view and in the third.

■Theme: healing through salvation and faith; Saint Sebastian (left) was saved after being shot by arrows; Saint Anthony (right) survived torments by devils and demons.

■Those suffering in the hospital were brought before this image, which symbolized heroism, sacrifice, and martyrdom.

■Ergotism causes convulsions and gangrene.

First view

■A scene of the crucifixion is in the center:

–Surrounded by a symbolically dark background.

–Christ’s body is dead with decomposing flesh emphasized as inspired by the writings by the mystic Saint Bridget.

–Christ’s arms are almost torn from their sockets.

–The body is lashed and whipped.

–The agony of the body is unflinchingly shown and acts as a symbol for the agony of ergotism.

■A lamb holds a cross, a common symbol for Christ, who is called the Lamb of God.

■A chalice catching the lamb’s blood parallels the chalice used to hold wine—the blood of Christ—during the Mass.

■The crucified body of Christ would have paralleled the raising of the sacramental bread called the Eucharist.

■A swooning Mary is dressed like the nuns who worked in the hospital.

■When panels open to reveal the next scene, Christ is amputated. Patients suffering from ergotism often endured amputation.

■Amputation also in the predella: Christ’s legs seem amputated below the kneecap.

Second view

■Marian symbols: the enclosed garden, closed gate, rosebush, rosary.

■Christ rises from the dead, on the right; his rags changed to glorious robes; he shows his wounds, which do not harm him now.

■Message to patients: earthly diseases and trials will vanish in the next world.

Third view

■Saint Anthony in the right panel has oozing boils, a withered arm, and a distended stomach: symbols of ergotism (this view is not illustrated on the AP exam).

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 77

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Pathos

–Seated boxer (Figure 4.10)

–Munch, The Scream (Figure 21.11)

–Kollwitz, Memorial Sheet for Karl Liebknecht (Figure 22.4)

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Allegory of Law and Grace, c. 1530, woodcut and letterpress (Figure 14.5)

Figure 14.5: Lucas Cranach the Elder, Allegory of Law and Grace, c. 1530, woodcut and letterpress

Function

■Designed using the woodcut technique to make the image available to the masses.

■Its purpose was to contrast the benefits of Protestantism versus the perceived disadvantages of Catholicism.

■Influential image of the Protestant Reformation; text appears in the people’s language: German, and not the church language: Latin.

Context

■Protestantism: the faithful achieve salvation by God’s grace; guidance can be achieved using the Bible.

■Meant to reflect the Lutheran ideas about salvation.

■Done in consultation with Martin Luther, a leader in the Protestant movement.

■Left: Last Judgment

–Moses holds the Ten Commandments.

–The Ten Commandments represent the Old Law, Catholicism.

–The Law of Moses is not enough; it is not enough to live a good life.

–A skeleton chases a man into hell.

■Right: Figure bathed in Christ’s blood

–Faith in Christ alone is needed for salvation.

–Symbolically, the barren branches of the tree on the left side contrast with the full bloom on the right.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 79

Web Source http://pitts.emory.edu/exhibits/exhibitcatalogs/LGCatalogFinal.pdf

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ideas and Rebellion

–Lawrence, The Migration of the Negro, Panel no. 49 (Figure 22.19)

–Michel Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000) (Figure 29.16)

–Neshat, Rebellious Silence (Figure 29.14)

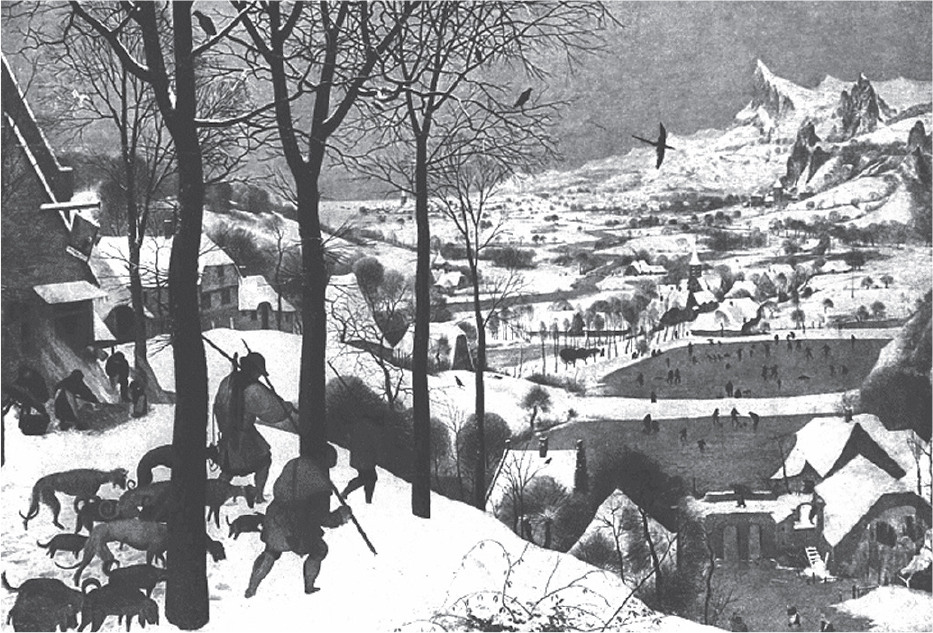

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow, 1565, oil on wood, Art History Museum, Vienna (Figure 14.6)

Figure 14.6: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow, 1565, oil on wood, Art History Museum, Vienna

Form

■Alpine landscape; typical winter scene inspired by the artist’s trips across the Alps to Italy.

■Strong diagonals lead the eye deeper into the painting.

■Figures are peasant types, not individuals.

■Landscape has high horizon line with panoramic views, a Northern European tradition.

■Extremely detailed.

Function

■One of a series of six paintings representing the labors of the months—this winter scene is November/December.

■Placed in a wealthy Antwerp merchant’s home.

■Patrons were wealthy individuals of high status; Bruegel’s paintings offered them a view of the world of the peasants.

Context

■Hunters have had little success in the winter hunt; dogs are skinny and hang their heads.

■Peasants in the sixteenth century were regarded as buffoons or figures of fun; Bruegel does not give them individuality but does treat them with respect.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 83

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/toah/hd/brue/hd_brue.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Hardship

–Turner, Slave Ship (Figure 20.5)

–Courbet, Stone Breakers (Figure 21.1)

–Stieglitz, The Steerage (Figure 22.8)

VOCABULARY

Altarpiece: a painted or sculpted panel set on an altar of a church

Annunciation: in Christianity, an episode in the Book of Luke 1:26–38 in which Angel Gabriel announces to Mary that she would be the Virgin Mother of Jesus (Figure 14.1)

Donor: a patron of a work of art, who is often seen in that work (Figure 14.1 left panel)

Engraving: a printmaking process in which a tool called a burin is used to carve into a metal plate, causing impressions to be made in the surface. Ink is passed into the crevices of the plate and paper is applied. The result is a print with remarkable details and finely shaded contours (Figure 14.3)

Etching: a printmaking process in which a metal plate is covered with a ground made of wax. The artist uses a tool to cut into the wax to leave the plate exposed. The plate is then submerged into an acid bath, which eats away at the exposed portions of the plate. The plate is removed from the acid, cleaned, and ink is filled into the crevices caused by the acid. Paper is applied and an impression is made. Etching produces the finest detail of the three types of early prints (Figure 17.9)

Oil paint: a paint in which pigments are suspended in an oil-based medium. Oil dries slowly allowing for corrections or additions; oil also allows for a great range of luster and minute details (Figure 14.2)

Polyptych: a many-paneled altarpiece

Predella: The base of an altarpiece that is filled with small paintings, often narrative scenes (Figures 14.4a and 14.4b)

Reformation: a division in western Christianity in which reformers broke away from the Catholic Church and formed a series of Protestant movements. It is considered to have started with the publication of the Ninety-five Theses by Martin Luther in 1517

Triptych: a three-paneled painting or sculpture (Figure 14.1)

Woodcut: a printmaking process by which a wooden tablet is carved into with a tool, leaving the design raised and the background cut away (very much as how a rubber stamp looks). Ink is rolled onto the raised portions, and an impression is made when paper is applied to the surface. Woodcuts have strong angular surfaces with sharply delineated lines (Figure 14.5)

SUMMARY

Northern European art from the fifteenth century is dominated by monumental altarpieces prominently erected in great cathedrals. Flemish artists delight in symbolically rich compositions that evoke a visually enticing experience along with a religiously sincere and intellectually challenging interpretation. The Flemish emphasis on minute details does not minimize the total effect. The introduction of oil paint provides a new luminous glow to Northern European works.

The invention of movable type brought about a revolution in the art world. Instead of producing individual items, artists could now make multiple images whose portability and affordability would ensure their widespread fame.

The achievements of Italian Renaissance painters had a profound effect on their Northern European counterparts in the sixteenth century. The monumentality of forms, particularly in the works of Michelangelo, were of great interest to Northern European artists, who traveled to Italy in great numbers. Even so, most Northern painters continued their own tradition of meticulously painting details, high horizon lines, and colorful surfaces that characterize their art.

The civil unrest that was an outgrowth of the Reformation caused many churches to be violated as works of art were smashed and destroyed because they were thought to be pagan. Protestants in general sought more austere church interiors in reaction against the perceived lavishness of their Catholic counterparts.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

Questions 1 and 2 refer to this image.

1.This work is both signed and dated, showing the growing status of artists. Which of the following works are also signed?

(A)Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis)

(B)Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

(C)Lamentation by Giotto

(D)Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci

2.This painting has been traditionally thought of as a wedding portrait. Which of the following has been interpreted as a wedding symbol?

(A)The burning candle, a custom on the first night of a wedding

(B)The inscription on the rear wall, which makes clear that a wedding contract has been signed

(C)The man’s fur coat, which is a typical garment for weddings

(D)The convex mirror, which reflects God’s blessing on this event

3.Altarpieces in Northern Europe during the Renaissance were different from their Italian counterparts in that the northern works

(A)are painted in tempera; Italian artists preferred oil

(B)rely on classical forms, which Italian artists rejected

(C)specialize in religious works, which Italian artists avoided

(D)fold closed as if they were cupboards; Italian works have one large dominant panel that does not fold closed

4.Woodcuts, such as Cranach’s Allegory of Law and Grace, enabled

(A)the artist to reach a wider audience with his ability to mass produce images

(B)the collector to display works that were resistant to fading and peeling

(C)the artist to use color in printmaking; before, only black and white was possible

(D)the artist for the first time to represent a scene three-dimensionally

5.Albrecht Dürer’s engraving of Adam and Eve references works of classical art for the forms of the two figures because it shows them as

(A)pagan and corrupt

(B)idealized before the Fall of Man

(C)saintly and holy

(D)concerned only about their physical appearance

Short Essay

Practice Question 5: Attribution

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

Attribute this painting to the artist who painted it.

Using at least two specific details, justify your attribution by describing relevant similarities between this work and a work in the required course content.

Using at least two specific details, explain why these visual elements are characteristic of this artist.

ANSWER KEY

1.A

2.A

3.D

4.A

5.B

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(A) The Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis) is signed (six times!) by Muhammad ibn al-Zain.

2.(A) All of the choices appear in the painting, but only the burning candle reflects a marriage custom.

3.(D) Northern works such as the Annunciation Triptych and the Isenheim altarpiece come in many sections and fold closed. Italian altarpieces tend to have one large scene that remains always viewable.

4.(A) Woodcuts made cheap mass-produced images available for a fraction of the cost of paintings. This enabled an artist’s reputation to spread very quickly.

5.(B) Dürer is representing people before the Fall of Man, and therefore perfect as God originally created them. It was after they sinned that their bodies became mortal and corruptible.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Attribute this painting to the artist who painted it. |

1 |

Pieter Bruegel the Elder |

Using at least two specific details, justify your attribution by describing relevant similarities between this work and a work in the required course content. |

2 |

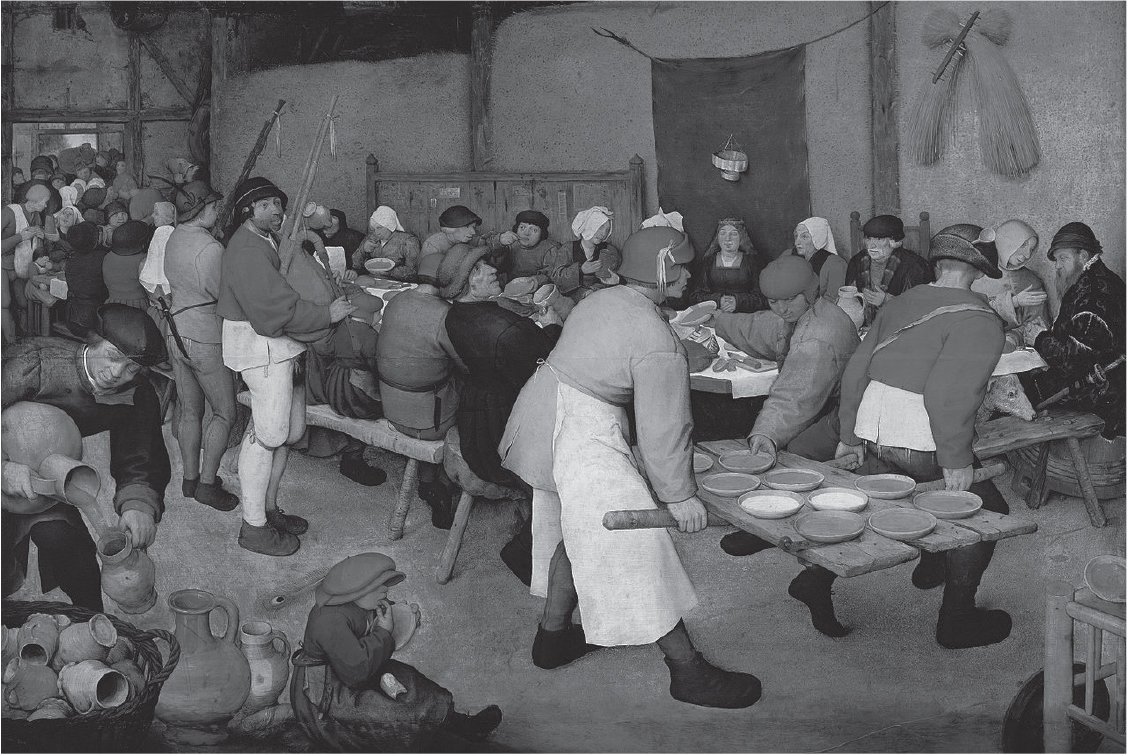

The work in the required course content is Hunters in the Snow. Answer could include: ■Peasants in everyday activities. ■Very detailed paintings. ■Strong receding diagonals. ■Gruff, but picturesque, view of country life. ■No central focus. |

Using at least two specific details, explain why these visual elements are characteristic of this artist. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■Rejection of Italian Renaissance ideals in art, including: –Not interested in symmetry and balance. –No classical idealization of forms. ■Bruegel gives the impression of the immediate and spontaneous; a moment in time. ■Bruegel has an affinity for genre scenes and landscapes. ■Bruegel’s extensive use of oil painting enables the artist to render great details and a luminous shine to his surfaces. |