Content Area: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 C.E.

TIME PERIOD

| Early Byzantine | 500–726 |

| Iconoclastic Controversy | 726–843 |

| Middle and Late Byzantine | 843–1453, and beyond |

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Hagia Sophia)

Essential Knowledge:

■Byzantine art is a medieval tradition.

■Byzantine art is inspired by the requirements of Christian worship.

■Byzantine art avoids naturalism and incorporates text into its images.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Vienna Genesis)

Essential Knowledge:

■Works of art were often displayed in religious and royal settings.

■Surviving architecture is mostly religious.

■Often there were reactions against figural imagery.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Justinian and Theodora panels from San Vitale)

Essential Knowledge:

■The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

■Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The term “Byzantine” would have sounded strange to residents of the Empire—they called themselves Romans. The Byzantine Empire was born from a split in the Roman world that occurred in the fifth century, when the size of the Roman Empire became too unwieldy for one ruler to manage effectively. The fortunes of the two halves of the Roman Empire could not have been more different. The western half dissolved into barbarian chaos, succumbing to hordes of migrating peoples. The eastern half, founded by Roman Emperor Constantine the Great at Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), flourished for one-thousand years beyond the collapse of its western counterparts. Culturally different from their Roman cousins, the Byzantines spoke Greek rather than Latin, and promoted orthodox Christianity, as opposed to western Christianity, which was centered in Rome.

The porous borders of the Empire expanded and contracted during the Middle Ages, reacting to external pressures from invading armies, seemingly coming from all directions. The Empire had only itself to blame: The capital, with its unparalleled wealth and opulence, was the envy of every other culture. Its buildings and public spaces awed ambassadors from around the known world. Constantinople was the trading center of early medieval Europe, directing traffic in the Mediterranean and controlling the shipment of goods nearly everywhere.

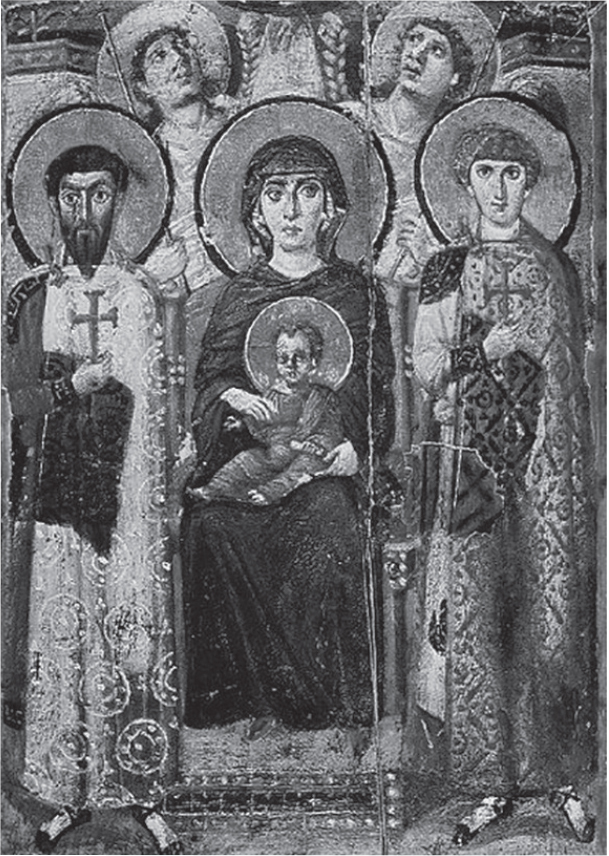

Icon production was a Byzantine specialty (Figure 8.8). Devout Christians attest that icons are images that act as reminders to the faithful; they are not intended to actually be the sacred persons themselves. However, by the eighth century, Byzantines became embroiled in a heated debate over icons; some even worshipped them as idols. In order to stop this practice, which many considered sacrilegious, the emperor banned all image production. Not content with stopping images from being produced, iconoclasts smashed previously created works. Perhaps the iconoclasts were inspired by religions, such as Judaism and Islam, which discouraged images of sacred figures for much the same reasons. The unfortunate result of this activity is that art from the Early Byzantine period (500–726) is almost completely lost. The artists themselves fled to parts of Europe where iconoclasm was unknown and Byzantine artists welcome. This so-called Iconoclastic Controversy serves as a division between the Early and Middle Byzantine art periods.

Despite the early successes of the iconoclasts, it became increasingly hard to suppress images in a Mediterranean culture such as Byzantium that had such a long tradition of creating paintings and sculptures of gods, going back to before the Greeks. In 843, iconoclasm was repealed and images were reinstated. This meant that every church and monastery had to be redecorated, causing a burst of creative energy throughout Byzantium.

Medieval Crusaders, some more interested in the spoils of war than the restoration of the Holy Land, conquered Constantinople in 1204, setting up a Latin kingdom in the east. Eventually the Latin invaders were expelled, but not before they brought untold damage to the capital, carrying off to Europe precious artwork that was simultaneously booty and artistic inspiration. The invaders also succeeded in permanently weakening the Empire, making it ripe for the Ottoman conquest in 1453. Even so, Late Byzantine artists continued to flourish both inside what was left of the Empire and in areas beyond its borders that accepted orthodoxy. A particularly strong tradition was established in Russia, where it remained until the 1917 Russian Revolution ended most religious activity. Even rival states, like Sicily and Venice, were known for their vibrant schools of Byzantine art, importing artists from the capital itself.

Patronage and Artistic Life

The church and state were one in the Byzantine Empire, so that many of the greatest works of art were commissioned, in effect, by both institutions at the same time. Monasteries were particularly influential, commissioning a great number of works for their private spaces. Interiors of Byzantine buildings were crowded with religious works competing with each other for attention.

A strong court atelier developed around a royal household interested in luxury objects. This atelier specialized in extravagant works in ivory, manuscripts, and precious metals.

Individual artists worked with great piety and felt they were executing works for the glory of God. They rarely signed their names, some feeling that pride was a sin. Many artists were monks, priests, or nuns whose artistic production was an expression of their religious devotion and sincerity.

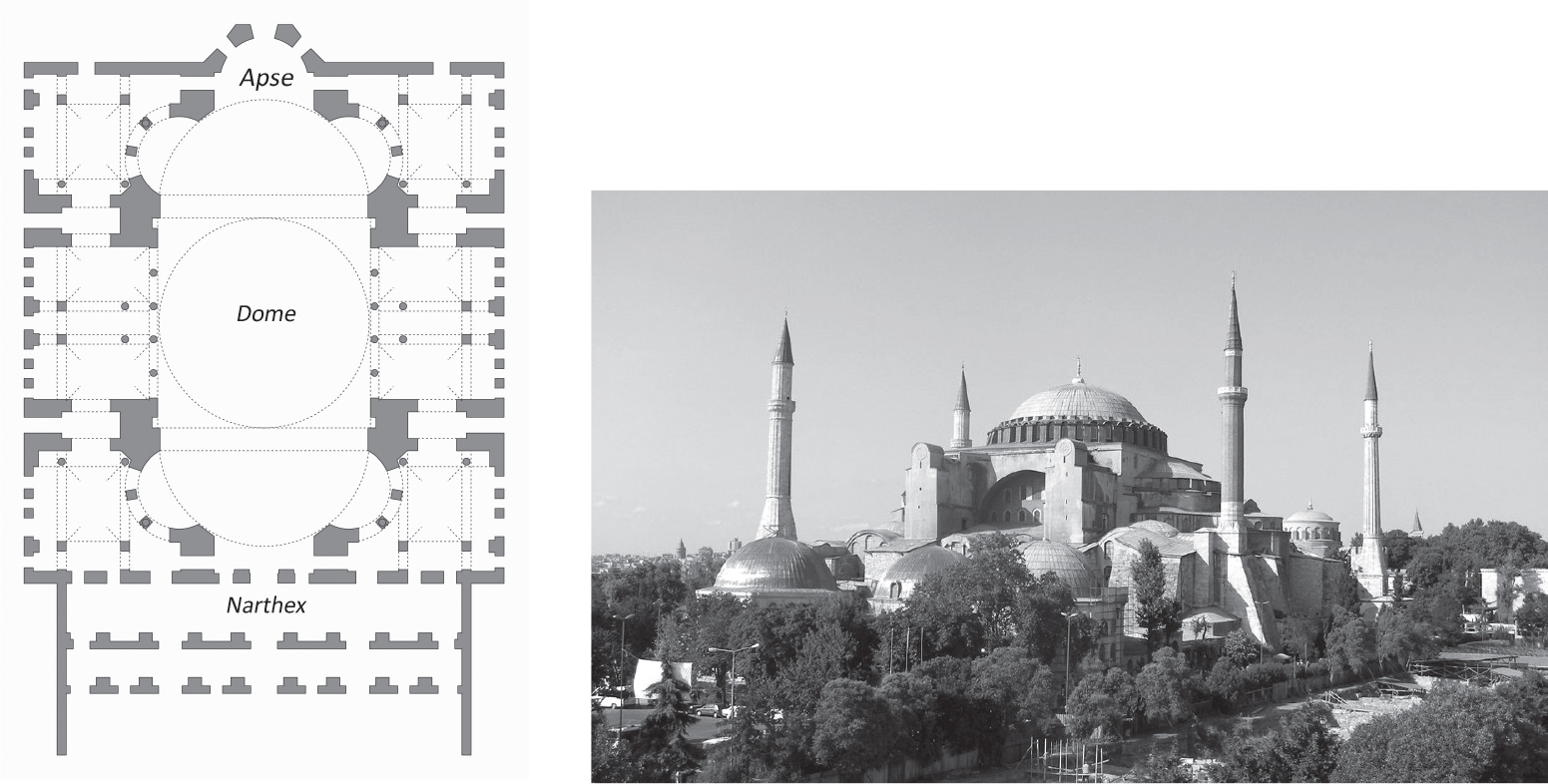

BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE

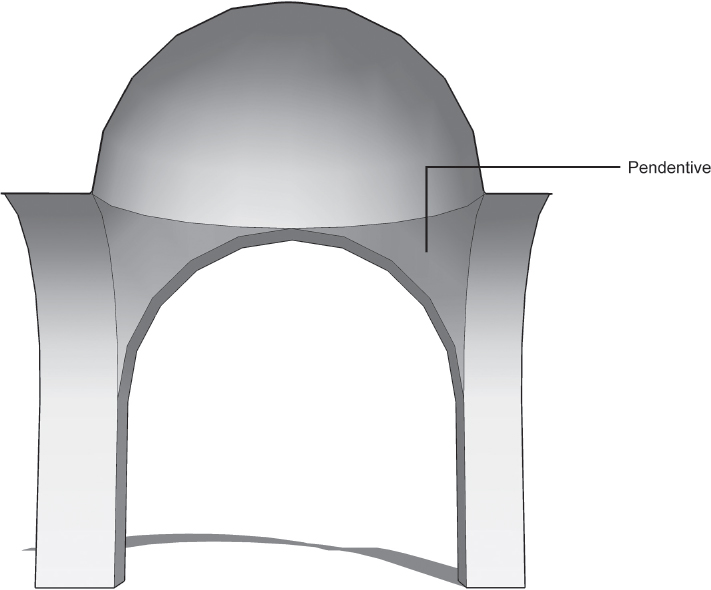

Byzantine architecture shows great innovation, beginning with the construction of the Hagia Sophia in 532 in Istanbul (Figures 8.3a, 8.3b, and 8.3c). The architects, Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus (actually a mathematician and a physicist rather than true architects), examined the issue of how a round dome, such as the one built for the Pantheon in Rome (Figure 6.11), could be placed on flat walls. Their solution was the invention of the pendentive (Figure 8.1), a triangle-shaped piece of masonry with the dome resting on one long side, and the other two sides channeling the weight down to a pier below. A pendentive allows the dome to be supported by four piers, one in each corner of the building. Since the walls between the piers do not support the dome, they can be opened up for greater window space. Thus the Hagia Sophia has walls of windows that flank the building on each side, unlike the Pantheon, which lacks windows, having only an oculus in the dome.

Figure 8.1: A dome supported by pendentives

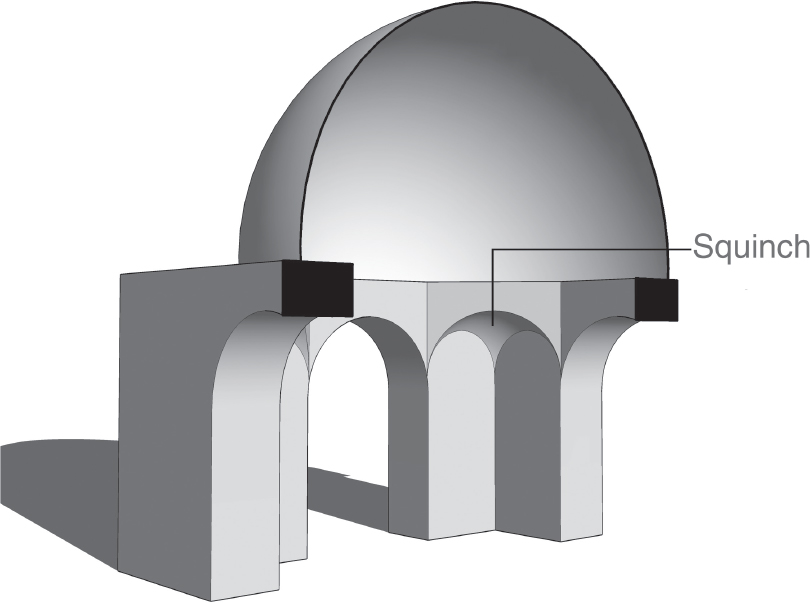

Middle and Late Byzantine architects introduced a variation on the pendentive called the squinch (Figure 8.2). Although fulfilling the same function as a pendentive, that is, transitioning the weight of a dome onto a flat rather than a rounded wall, a squinch can take a number of shapes and forms, some corbelling from the wall behind, others arching into the center space. Architects designed pendentives and squinches so that artists could later use these broad and protruding surfaces as painted spaces.

Figure 8.2: A dome supported by squinches

The Hagia Sophia’s dome is composed of a set of ribs meeting at the top. The spaces between those ribs do not support the dome and are opened for window space. The Hagia Sophia has forty windows around the base of the dome, forming a great circle of light (or halo) over the congregation.

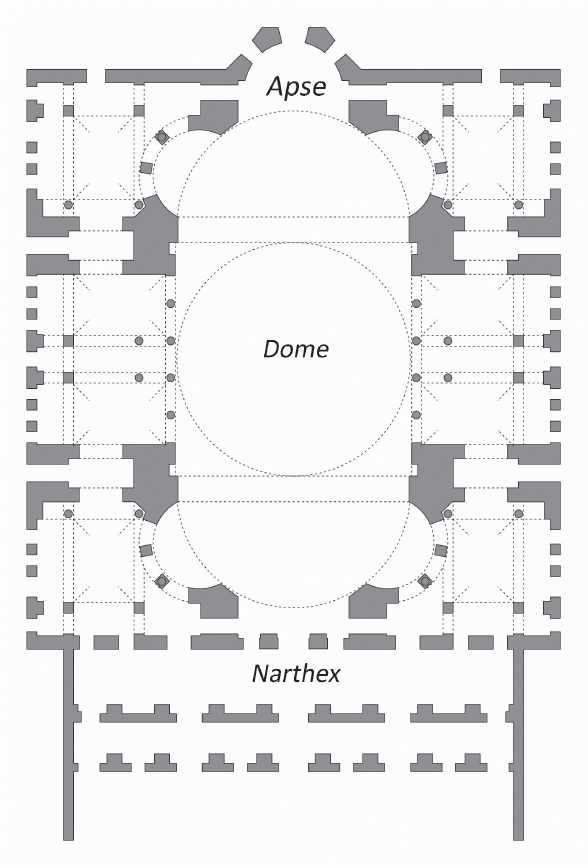

A further innovation in the Hagia Sophia involves its ground plan (Figure 8.3c). Churches in the Early Christian era concentrate on one of two forms: the circular building containing a centrally planned apse and the longer basilica with an axially planned nave facing an altar. The Hagia Sophia shows a marriage of these two forms, with the dome emphasizing a centrally planned core and the long nave directing focus toward the apse.

Except for the Hagia Sophia, Byzantine architecture is not known for its size. Buildings in the Early period (500–726) have plain exteriors made of brick or concrete. In the Middle and Late periods (843–1453), the exteriors are richly articulated with a provocative use of various colors of brick, stone, and marble, often with contrasting vertical and horizontal elements. The domes are smaller, but there are more of them, sometimes forming a cross shape.

Figure 8.3a: Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus, Hagia Sophia, 532–537, brick and ceramic elements, with stone and mosaic veneer, Constantinople (Istanbul)

Interiors are marked by extensive use of variously colored marbles on the lower floors and mosaics or frescoes in the elevated portions of the buildings. Domes tend to be low rather than soaring, having windows around the base. Interior arches reach into space, creating mysterious areas clouded by half-lights and shimmering mosaics. These buildings usually set the domes on more elevated drums.

Greek Orthodox tradition dictates that important parts of the Mass take place behind a curtain or screen. In some buildings this screen is composed of a wall of icons called an iconostasis.

Figure 8.3b: Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus, Hagia Sophia, 532–537, Constantinople (Istanbul)

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus, Hagia Sophia, 532–537, brick and ceramic elements, with stone and mosaic veneer, Constantinople (Istanbul) (Figures 8.3a, 8.3b, and 8.3c)

Form

■Exterior: plain and massive with little decoration.

■Interior:

–Combination of centrally and axially planned church.

–Arcade decoration: walls and capitals are flat and thin and richly ornamented.

–Capitals diminish classical allusions; surfaces contain deeply cut acanthus leaves.

–Cornice unifies space.

–Large fields for mosaic decoration; at one time there were four acres of gold mosaics on the walls.

–Many windows punctuate wall spaces.

■Dome: the first building to have a dome supported by pendentives.

–Altar at end of nave, but emphasis placed over the area covered by the dome.

–Large central dome, with 40 windows at base symbolically acting as a halo over the congregation when filled with light.

Function

■Originally a Christian church; Hagia Sophia means “holy wisdom.”

■Built on the site of another church that was destroyed during the Nike Revolt in 532.

■Converted to a mosque in the fifteenth century; minarets added in the Islamic period.

■Converted into a museum in 1935.

Figure 8.3c: Ground plan of Hagia Sophia

Context

■Marble columns appropriated from Rome, Ephesus, and other Greek sites.

■Patrons were Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora, who commissioned the work after the burning of the original building in the Nike Revolt.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 52

Web Source https://www.ktb.gov.tr/EN-113776/ayasofya-hagia-sophia.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Buildings that Have Changed Use

–Parthenon (Figure 4.16b)

–Pantheon (Figures 6.11a, 6.11b)

–Great Mosque at Córdoba (Figures 9.14a, 9.14b, 9.14c, 9.14d, 9.14e)

Figure 8.4a: San Vitale, Early Byzantine Europe, 526–547, brick, marble, and stone veneer, Ravenna, Italy

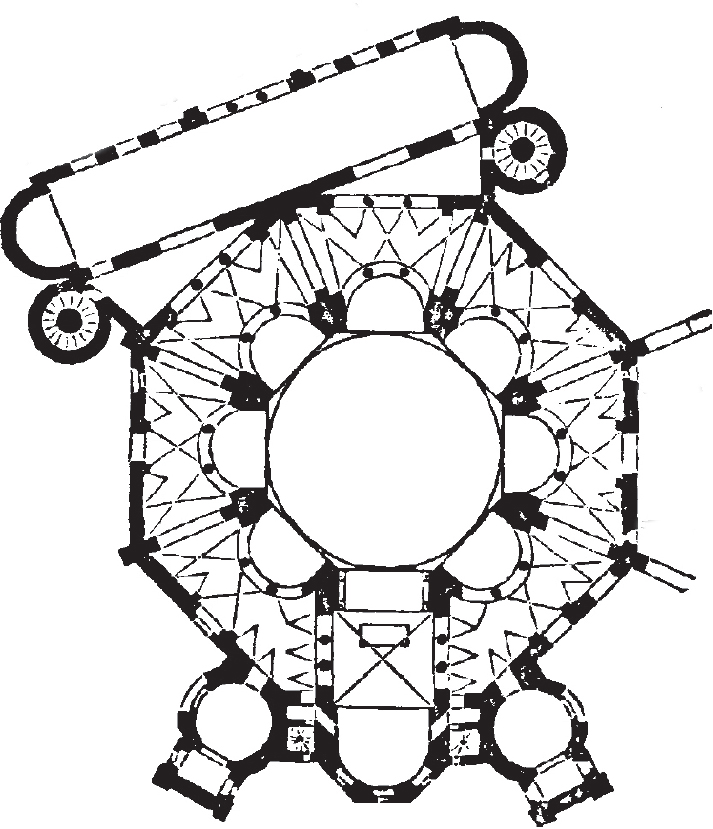

San Vitale, Early Byzantine Europe, 526–547, brick, marble, and stone veneer, Ravenna, Italy (Figures 8.4a, 8.4b, and 8.4c)

Form

■Eight-sided church.

■Plain exterior; porch added later, in the Renaissance.

■Large windows for illuminating interior designs.

■Interior has thin columns and open arched spaces.

■Dematerialization of the mass of the structure.

■Combination of axial and central plans.

■Spolia: bricks taken from ruined Roman buildings reused here.

■Martyrium design: circular plan in an octagonal format.

Figure 8.4b: San Vitale interior, 526–547, Ravenna, Italy

Function

■Christian church.

Context

■Mysterious space symbolically connects with the mystic elements of religion.

■Banker Julianus Argentarius financed the building of San Vitale.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 51

Web Source http://www.ravennamosaici.it/?lang=en

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Buildings with Circular Plans

–Pantheon (Figures 6.11a, 6.11b)

–Dome of the Rock (Figures 9.12a, 9.12b)

–Mosque of Selim II (Figures 9.16a, 9.16b, 9.16c)

Figure 8.4c: San Vitale plan, 526–547, Ravenna, Italy

BYZANTINE PAINTING

The most characteristic work of Byzantine art is the icon, a religious devotional image usually of portable size and hanging in a place of honor either at home or in a religious institution. An icon has a wooden foundation covered by preparatory undercoats of paint, sometimes composed of such things as fish glue or putty. Cloth is placed over this base, and successive layers of stucco are gently applied. A perforated paper sketch is placed on the surface, so that the image can be traced and then gilded and painted. The artist then applies varnish to make the icon shine, as well as to protect it, because icons are often touched, handled, and embraced. The faithful were encouraged to kiss icons and burn votive candles beneath them; as a result, icons have become blackened by candle soot and incense, their frames singed by flames. Consequently, many icons have been repainted and no longer have their original surface texture.

Icons were paraded in religious processions on feast days, and sometimes exhibited on city walls in times of invasion. Frequently they were believed to possess spiritual powers, and they held a sacred place in the hearts of Byzantine worshippers.

Byzantine painting is marked by a combination of the classical heritage of ancient Greece and Rome with a more formal and hieratic medieval style. Artists are trained in one tradition or the other, and it is common to see a single work of art done by a number of artists, some inspired by the classical tradition, and others by medieval formalism. The Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (Figure 8.8) shows both traditions.

Those artists who were classically trained used a painterly brushstroke and an innovative way of representing a figure—typically from an unusual angle. These artists employed soft transitions between color areas and showed a more relaxed figure stance.

Those trained in the medieval tradition favored frontal poses, symmetry, and almost weightless bodies. The drapery is emphasized, so there is little effort to reveal the body beneath. Perspective is unimportant because figures occupy a timeless space, marked by golden backgrounds and heavily highlighted halos.

Whatever the tradition, Byzantine art, like all medieval art, avoids nudity whenever possible, deeming it debasing. Nudity also had a pagan association, connected with the mythological religions of ancient Greece and Rome.

One of the glories of Byzantine art is its jewel-like treatment of manuscript painting. The manuscript painter had to possess a fine eye for detail, and so was trained to work with great precision, rendering minute details carefully. Byzantine manuscripts are meticulously executed; most employ the same use of gold seen in icons and mosaics. Because so few people could read, the possession of manuscripts was a status symbol, and libraries were true temples of learning. The Vienna Genesis (Figures 8.7a and 8.7b) is an excellent example of the sophisticated court style of manuscript painting.

Byzantine art continues the ancient traditions of fresco and mosaic painting, bringing the latter to new heights. Interior church walls are covered in shimmering tesserae made of gold, colored stones, and glass. Each piece of tesserae is placed at an odd angle to catch the flickering of candles or the oblique rays of sunlight; the interior then resembles a vast glittering world of floating golden shapes, perhaps echoing what the Byzantines thought heaven itself would resemble.

Court customs play an important role in Byzantine art. Purple, the color usually reserved for Byzantine royalty, can be seen in the mosaics of Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora. However, in an act of transference, purple is sometimes used on the garments of Jesus himself. Custom at court prescribed that courtiers approach the emperor with their hands covered as a sign of respect. As a result, nearly every figure has at least one hand covered before someone of higher station, sometimes even when he or she is holding something. Justinian himself (Figure 8.5), in his famous mosaic in San Vitale, holds a paten with his covered hand.

Facial types are fairly standardized. There is no attempt at psychological penetration or individual insight: Portraits in the modern sense of the word are unknown. Continuing a tradition from Roman art, eyes are characteristically large and wide open. Noses tend to be long and thin, mouths short and closed. The Christ Child, who is a fixture in Byzantine art, is more like a little man than a child, perhaps showing his wisdom and majesty. Medieval art generally labels the names of figures the viewer is observing, and Byzantine art is no exception.

Typically, most paintings have flattened backgrounds, often with just a single layer of gold to symbolize an eternal space. This becomes increasingly pronounced in the Middle and Late Byzantine periods in which figures stand before a monochromatic of golden opulence, perhaps illustrating a heavenly world.

Justinian Panel, c. 547, mosaic from San Vitale, Ravenna (Figure 8.5)

Content

■Emperor Justinian, as the central image, dominates all; emperor’s rank indicated by his centrality, halo, fibula, and crown.

■To his left the clergy, to his right the military.

■Dressed in royal purple and gold.

■Divine authority symbolized by the halo; Justinian is establishing religious and political control over Ravenna.

Form

■Symmetry, frontality.

■Slight impression of procession forward.

■Figures have no volume; they seem to float and yet step on each other’s feet.

■Minimal background: green base at feet; golden background indicates timelessness.

Figure 8.5: Justinian Panel, c. 547, mosaic from San Vitale, Ravenna

Function

■Justinian holds a paten, or plate, for the Eucharist; participating in the service of the Mass almost as if he were a celebrant—his position over the altar enhances this reference.

■Justinian appears as head of church and state; regent of Christ on earth.

Context

■Archbishop Maximianus is identified; he is the patron of San Vitale.

■XP or Chi Rho, the monogram of Christ, on soldier’s shield shows them as defenders of the faith, or Christ’s soldiers on earth.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 51

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Mosaics

–Alexander Mosaic (Figure 4.20)

–Dome of the Rock interior (Figure 9.12b)

Theodora Panel, c. 547, mosaic from San Vitale, Ravenna (Figure 8.6)

Content

■Empress Theodora stands in an architectural framework holding a chalice for the Mass and is about to go behind the curtain.

Form

■Slight displacement of absolute symmetry with Empress Theodora; she plays a secondary role to her husband.

■She is simultaneously frontal and moving to our left.

■Figures are flattened and weightless; barely a hint of a body can be detected beneath the drapery.

Function

■She holds a chalice for the wine; participating in the service of the Mass almost as if she were a celebrant.

■She is juxtaposed with Emperor Justinian on the flanking wall; both figures hold the sacred items for the Mass.

Context

■Richly robed empress and ladies at court.

■The three Magi, who bring gifts to the baby Jesus, are depicted on the hem of her dress. This reference draws parallels between Theodora and the Magi.

Figure 8.6: Theodora Panel, c. 547, mosaic from San Vitale, Ravenna

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 51

Web Source http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/ARTH/arth212/san_vitale.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Role of Women in Positions of Power

–Kneeling statue of Hatshepsut (Figure 3.9b)

–Presentation of Fijian mats and tapa cloths to Queen Elizabeth II (Figure 28.10)

–Olowe of Ise, veranda post of enthroned king and senior wife (Figure 27.14)

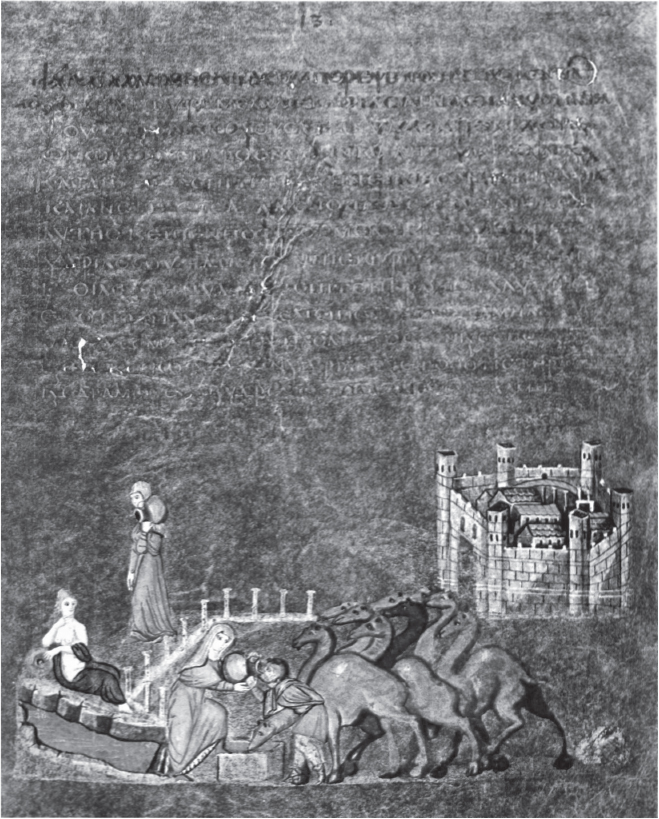

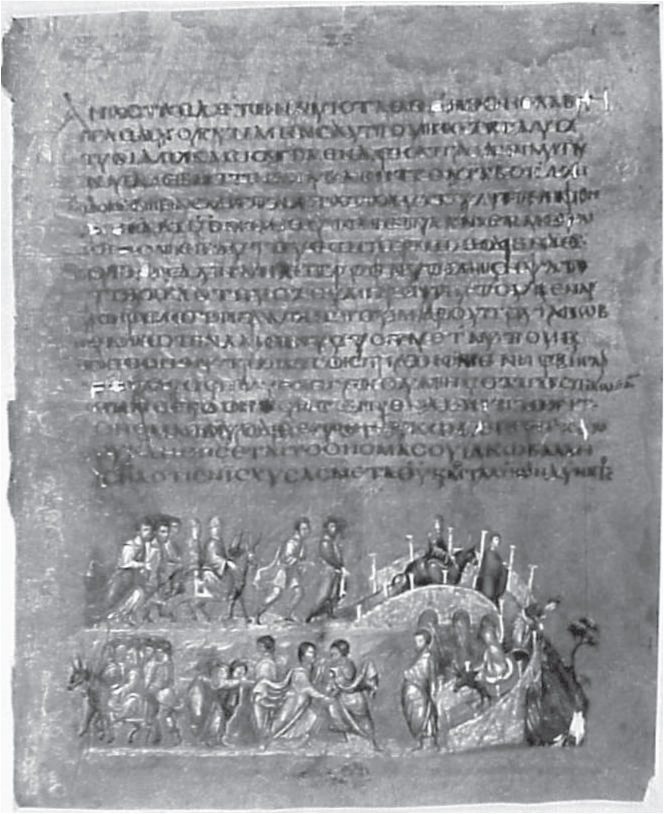

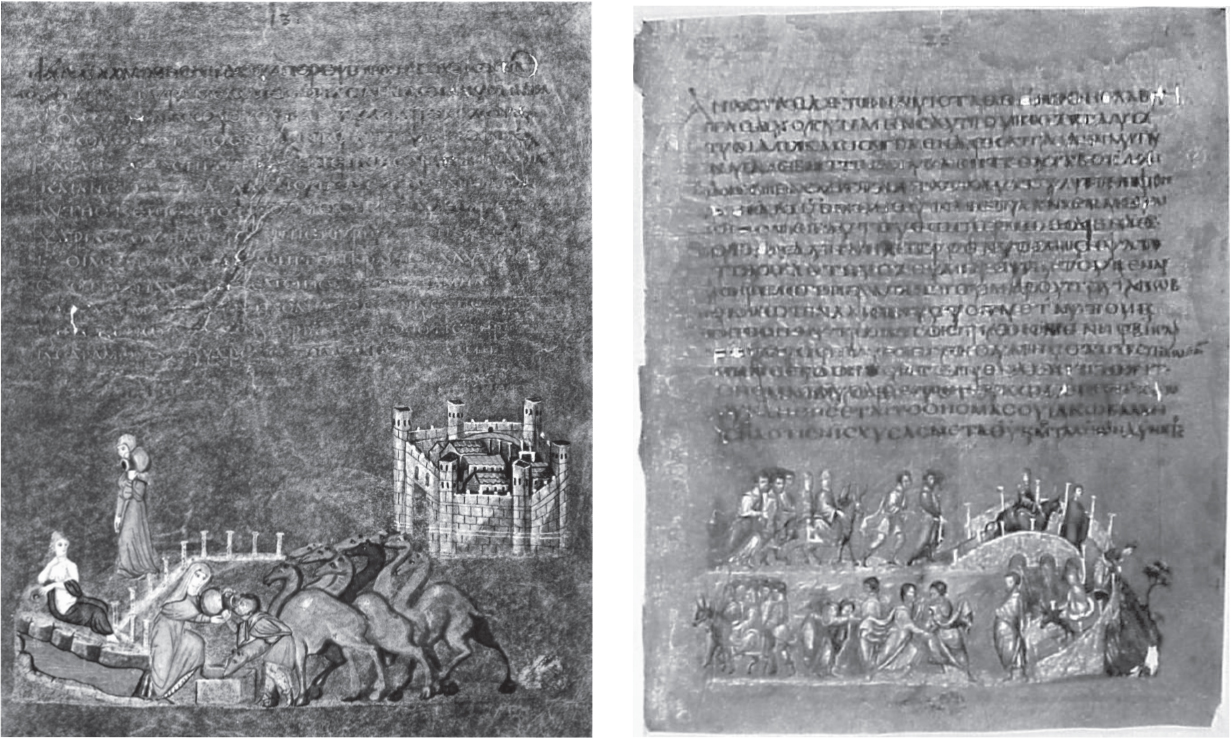

Vienna Genesis, Early Byzantine Europe, early 6th century, illuminated manuscript, tempera, gold, and silver on purple vellum, Austrian National Library, Vienna (Figures 8.7a and 8.7b)

Form

■Lively, softly modeled figures.

■Classical training of the artists: contrapposto, foreshortening, shadowing, perspective, classical allusions.

■Shallow settings.

■Fluid movement of decorative figures.

■Richly colored and shaded.

■Two rows linked by a bridge or a pathway.

■Text placed above illustrations, which are on the lower half of the page.

■Continuous narrative.

Context

■First surviving illustrations of the stories from Genesis.

■Genesis stories are done in continuous narrative with genre details.

■Written in Greek.

■Partial manuscript: 48 of 192 (?) illustrations survive.

Materials and Origin

■Manuscript painted on vellum.

■Written in silver script, now oxidized and turned black.

■Origin uncertain: a scriptorium in Constantinople? Antioch?

■Perhaps done in a royal workshop; purple parchment is a hallmark of a royal institution.

Figure 8.7a: Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, from the Vienna Genesis, Early Byzantine Europe, early 6th century, illuminated manuscript, tempera, gold, and silver on purple vellum, Austrian National Library, Vienna

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well

■Genesis 24: 15–61.

■Rebecca, shown twice, emerges from the city of Nahor with a jar on her shoulder to go down to the spring.

■She quenches the thirst of a camel driver, Eliezer, and his camels.

■Colonnaded road leads to the spring.

■Roman water goddess personifies the spring.

Jacob Wrestling the Angel

■Genesis 32: 22–31.

■Jacob takes his two wives, two maids, and eleven children and crosses a river; the number of children is abbreviated.

■At night Jacob wrestles an angel.

■The angel strikes Jacob on the hip socket.

■Classical influence in the Roman-designed bridge, but medieval influence in the bridge’s perspective: i.e., the shorter columns are placed in the nearer side of the bridge and the taller columns behind the figures.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 50

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Age_of_Spirituality_Late_Antique_and_Early_Christian_Art_Third_to_Seventh_Century p. 458 ff.

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Narrative

–Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace (Figures 25.3a, 25.3b)

–Last judgment of Hunefer (Figure 3.12)

–Churning of the Ocean of Milk (Figure 23.8c)

Figure 8.7b: Jacob Wrestling the Angel, from the Vienna Genesis, Early Byzantine Europe, early 6th century, illuminated manuscript, tempera, gold, and silver on purple vellum, Austrian National Library, Vienna

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George, Early Byzantine Europe, 6th or early 7th centuries, encaustic on wood, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, Egypt (Figure 8.8)

Function

■Icon placed in a medieval monastery for devotional purposes.

Content and Form

■Virgin and Child centrally placed; firmly modeled.

–Mary as Theotokos, mother of God.

–Mary looks beyond the viewer as if seeing into the future.

–Christ child looks away, perhaps anticipating his crucifixion.

■Saints Theodore and George flank Virgin and Child.

–Warrior saints.

–Stiff and hieratic.

–Directly stare at the viewer; engage the viewer directly.

■Angels in background look toward heaven.

–Painted in a classical style with brisk brushwork in encaustic, a Roman tradition.

–Turned toward the descending hand of God, which comes down to bless the scene.

■Because the three groups are in very different styles, it has been assumed that they were painted by three different artists.

Figure 8.8: Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George, Early Byzantine Europe, 6th or early 7th centuries, encaustic on wood, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, Egypt

Context

■Pre–Iconoclastic Controversy icon, location in the Sinai and encaustic places it near Roman-Egyptian encaustic painted portraits.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 54

Web Source https://www.sinaimonastery.com/index.php/en/treasures/icons

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: A Work of Art Done by Many Artists

–Terra cotta warriors (Figures 24.8a, 24.8b)

–Parthenon (Figures 4.16a, 4.16b)

–Koons, Pink Panther (Figure 29.9)

VOCABULARY

Axial plan (Basilican plan, Longitudinal plan): a church with a long nave whose focus is the apse, so-called because it is designed along an axis

Cathedral: the principal church of a diocese, where a bishop sits (Figure 8.3a)

Central plan: a church having a circular plan with the altar in the middle

Chalice: a cup containing wine, used during a Christian service (Figure 8.6)

Codex (plural: codices): a manuscript book (Figures 8.7a and 8.7b)

Continuous narrative: a work of art that contains several scenes of the same story painted or sculpted in continuous succession (Figure 8.7)

Cornice: a projecting ledge over a wall (Figure 8.3b)

Encaustic: a type of painting in which colors are added to hot wax to affix to a surface. (Figure 8.8)

Eucharist: the bread sanctified by the priest at the Christian ceremony commemorating the Last Supper

Genesis: first book of the Bible that details Creation, the Flood, Rebecca at the Well, and Jacob Wrestling the Angel, among other episodes (Figures 8.7a and 8.7b)

Icon: a devotional panel depicting a sacred image (Figure 8.8)

Iconoclastic controversy: the destruction of religious images in the Byzantine Empire during the eighth and ninth centuries.

Iconostasis: a screen decorated with icons, which separates the apse from the transept of a church

Illuminated manuscript: a manuscript that is hand decorated with painted initials, marginal illustrations, and larger images that add a pictorial element to the written text (Figures 8.7a and 8.7b)

Martyrium (plural: martyria): a shrine built over a place of martyrdom or a grave of a martyred Christian saint

Mosaic: a decoration using pieces of stone, marble or colored glass, called tesserae, that are cemented to a wall or a floor (Figures 8.5 and 8.6)

Paten: a plate, dish, or bowl used to hold the Eucharist at a Christian ceremony (Figure 8.5)

Pendentive: a construction shaped like a triangle that transitions the space between flat walls and the base of a round dome (Figure 8.1)

Squinch: the polygonal base of a dome that makes a transition from the round dome to a flat wall (Figure 8.2)

Theotokos: the Virgin Mary in her role as the Mother of God (Figure 8.8)

XP: the Christian monogram made up of the Greek letters khi and rho, the first two letters of Khristos, the Greek form of Christ’s name (Figure 8.5)

SUMMARY

The Eastern half of the Roman Empire lived for another one thousand years beyond the fall of Rome under a name we today call Byzantine. The Empire produced lavish works of art for a splendid court that resided in Constantinople—one of the most resplendent cities in history.

Byzantine art specialized in a number of diverse art forms. Walls were covered in shimmering gold mosaic that reflected a heavenly world of great opulence. Icons that were sometimes thought to have spiritual powers were painted of religious figures. Ivories were carved with consummate precision and skill.

Byzantine builders invented the pendentive, first seen at the Hagia Sophia. However, in later buildings the squinch was preferred.

The death of the Empire in 1453 did not mean the end of Byzantine art. Indeed, a second life developed in Russia, in eastern Europe, and in occupied Greece lasting into the twentieth century.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.Interior mosaic decoration is different in Late Antique and Byzantine buildings than in that of the ancient world in that

(A)ancient mosaicists used large blocks of stone rather than miniature pieces called tesserae.

(B)tiles were made from glass, whereas Byzantine tiles were made of metal

(C)tiles depicted animals and vegetable forms; Byzantine mosaics depict people

(D)tiles are colored in flat pastel shades; Byzantine tiles glow with a use of gold and sparkling colors

Questions 2 and 3 refer to the following images.

2.The ground plan of the Hagia Sophia suggests that

(A)columns are used as decorative patterning rather than as internal supports

(B)it is a combination of a central and a basilican plan

(C)the mihrab faces Mecca

(D)the Roman basilican type has been altered to create side aisles

3.Later additions to the original construction of this church included

(A)enlargement of windows

(B)development of rib vaults

(C)installation of underground catacombs

(D)addition of minarets

4.The mosaics of Justinian and Theodora have been placed in San Vitale

(A)to commemorate a state visit by the Emperor and Empress

(B)as a thank you for helping to construct the building

(C)to symbolize their semidivine status as participants in the Mass

(D)because they were declared saints after they died

5.After the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, its artistic tradition was carried on in

(A)Turkey

(B)Russia

(C)Austria

(D)Spain

Short Essay

Practice Question 4: Contextual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

The illustrations below are pages from the Vienna Genesis: Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well on the left and Jacob Wrestling the Angel on the right.

What is the written source of the images in this manuscript?

Describe at least two elements of the work that indicate an imperial or royal patronage.

The scenes have a number of motifs taken from classical art. Using specific details, analyze how these settings are incorporated into the text.

The scenes have a number of motifs taken from classical art. Using specific details, analyze why these settings are incorporated into the text.

ANSWER KEY

1.D

2.B

3.D

4.C

5.B

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(D) Byzantine mosaics are characterized by their glowing golden colors; Roman and Greek mosaicists use pastel colors.

2.(B) The Hagia Sophia was constructed as a combination of the central plan (dome sitting on pendentives) and a basilican plan (long nave terminating at an apse).

3.(D) The minarets were added by the Muslims when the building was turned into a mosque.

4.(C) There is no evidence that either Justinian or Theodora ever visited or financially supported San Vitale. Even though they wear halos, they were never declared saints after their death. Their presence and their halos suggest a semidivine presence at services.

5.(B) After the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the Byzantine artistic tradition was carried on in Russia.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

|

What is the written source of the images in this manuscript? |

1 |

The manuscript source is the Book of Genesis, Chapters 24 and 32, or more generally, the Hebrew Scriptures. |

|

Describe at least two elements of the work that indicate an imperial or royal patronage. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■Work done on vellum, a luxurious, expensive product. ■Painted with silver ink (now oxidized and turned black). ■Purple parchment is a hallmark of a royal institution. |

|

The scenes have a number of motifs taken from classical art. Using specific details, analyze how these settings are incorporated into the text. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Classical training of the artists: contrapposto, foreshortening, shadowing, perspective. ■In Rebecca: –Roman water goddess personifies the spring. –Colonnaded road leads to the spring. ■In Jacob: –Roman-style bridge. |

|

The scenes have a number of motifs taken from classical art. Using specific details, analyze why these settings are incorporated into the text. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■The Byzantines called themselves Romans and saw themselves as continuing in this tradition. ■Classical style references the antique world and great epic moments in ancient history. |