Content Area: South, East, and Southeast Asia, 300 B.C.E.–1980 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: 1789–1848

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Hokusai, the Great Wave)

Essential Knowledge:

■The art of Japan is some of the oldest in the world with the longest continuous tradition.

■Distinctive to Japan is the development of rock gardens, teahouses, and wood-block printing.

■Japanese architecture uses natural materials such as wood and stone.

■Calligraphy is highly prized in Japan.

■Elaborate floral and animal-inspired artwork is a Japanese specialty.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Dry garden at Ryoan-ji)

Essential Knowledge:

■Ancient Japanese civilizations were very advanced for their time.

■Shared cultural ideas throughout Asia stimulated artistic production.

■Figural subjects are common in Japanese painting.

■Zen rock gardens and ink paintings were popular in Japan.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Ogata Korin, White and Red Plum Blossoms)

Essential Knowledge:

■Japanese art featured a counterculture approach that highlighted the achievements of nonprofessional artists with new types of subject matter.

■Architecture is generally religious.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Great Buddha at Todai-ji)

Essential Knowledge:

■Asian art is influenced by global trends, and in turn influences global trends.

■Trade routes connected Asia with the world.

■Buddhism was imported from Korea and China and was widely popular in part because of courtly patronage.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Nio guardian figures)

Essential Knowledge:

■Art history as a science is subject to differing interpretations and theories that change over time.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Japan is one of the few countries in the world that has never been successfully invaded by an outside army. There are those who have tried, like the Mongols in 1281, whose fleet was destroyed by a typhoon called a kamikaze, or divine wind, and there are those who have defeated the Japanese without invading, like the Allies in World War II, who never landed a force on the four principal islands, until the war was over.

Because of the relatively sheltered nature of the Japanese archipelago, and the infrequency of foreign interference, Japan has a greater proportion of its traditional artistic patrimony than almost any other country in the world. It was Commodore Perry who opened Japan, to outside influence in 1854. One by-product of Perry’s intervention was the shipment of ukiyo-e prints to European markets, first as packing material and then in their own right. They achieved enduring fame in nineteenth-century Europe and America, but were looked down upon by the upper classes in Japan, who were more than willing to send them off for export.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Japanese artists worked on commission, some for the royal court, others in the service of religion. Masters ran workshops with a range of assistants—the tradition in Japan usually marking this as a family-run business with the eldest son inheriting the trade. Assistants learned from the ground up, making paper and ink, for example. The master created the composition by brushing in key outlines and his assistants worked on the colors and details.

Painting is highly esteemed in Japan. Aristocrats of both sexes not only learned to paint, but became distinguished in the art form.

ZEN BUDDHISM

Zen is a school of Buddhism that is deeply rooted in all East Asian societies, and was imported from China in the late twelfth century. It had a particularly great impact on the art of Japan, where the Zen philosophy was warmly embraced.

Zen adherents reject worldliness, the collection of goods for their own sake, and physical adornment. Instead, the Zen world is centered on austerity, self-control, courage, and loyalty. Meditation is key to enlightenment; for example, samurai warriors reach deeply into themselves to perform acts of bravery and great physical endurance.

Zen teaches through intuition and introspection, rather than through books and scripture. Warriors as well as artists were quick to adopt a Zen philosophy.

THE JAPANESE TEA CEREMONY

The tea ceremony is a ritual of greater importance than it at first seems to the Westerner. The simple details, the crude vessels, the refined tea, the uncomplicated gestures—these alluring items are all part of a seemingly casual, but in fact, highly sophisticated tea ceremony that endures because of its minimalism. Teahouses have bamboo and wooden walls with floor mats of woven straw. Everything is carefully arranged to give the sense of straightforwardness and delicacy.

Visitors enter through a low doorway—symbolizing their humbleness—into a private setting. Rectangular spaces are broken by an unadorned alcove that houses a Zen painting done in a free and monochromatic style, selected to enhance an intimate atmosphere of warm and dark spaces.

Participants sit on the floor in a small space usually designed for about five people, and drink tea. The ceremony requires four principles: Purity, harmony, respect, and tranquility. All elements of the ceremony are proscribed, even the purification ritual of hand washing and the types of conversation allowed.

JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURE

The austerity of Zen philosophy can be most readily seen in the simplicity of architectural design that dominates Japanese buildings. A traditional structure is usually a single story, made of wood, and meant to harmonize with its natural environment. The wood is typically undressed—the fine grains appreciated by the Japanese. Because wood is relatively light, the pillars could be placed at wide intervals to support the roof, opening the interior most dramatically to the outdoors.

Floors are raised above the ground to reduce humidity by allowing the air to circulate under the building. Eaves are long to generate shady interiors in the summer, and steeply pitched to allow the quick runoff of rain and snow.

Interiors have mobile spaces created by sliding screens, which act as room dividers, by changing its dimensions at will. Particularly lavish homes may have gilded screens, but most are of wooden materials. The floors are overlaid with removable straw mats.

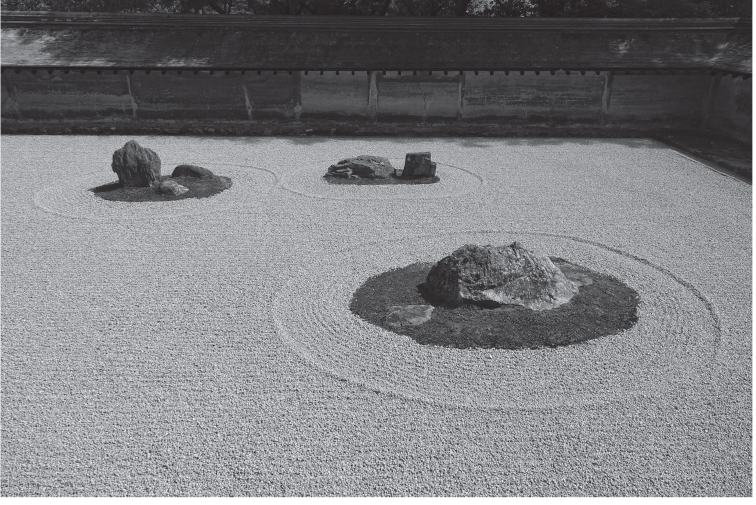

A principal innovation in Japanese design is the Zen garden, which features meticulous arrangements of raked sand circling around prominently placed stones and plants (Figure 25.2b). Each garden suggests wider vistas and elaborate landscapes. Zen gardens contain no water, but the careful placement of rocks often suggests a cascade or a rushing stream. Ultimately these gardens serve for spiritual refreshment, a place of contemplation and rejuvenation.

There is a deep respect for the natural world in Japanese thought. The native religion, Shintoism, believes in the sacredness of spirits inherent in nature. In a heavily forested and rocky terrained country like Japan, wood becomes the natural choice for building, and stone for Zen gardens.

Todai-ji, 743, rebuilt c. 1700, wood with ceramic tile roofing, Nara, Japan (Figure 25.1a)

Figure 25.1a: Todai-ji, 743, rebuilt c. 1700, wood with ceramic tile roofing, Nara, Japan

Various artists including sculptors Unkei and Keikei, as well as the Kei school.

Form

■A two-story building with long, graceful eaves hanging over the edges: the eaves protect the interior from the sun and rain.

■Seven external bays on the façade.

Function

■This is the original center of the Buddhist faith in Japan, from which ancillary temples around the country were served.

■The building expresses an imperial and political authority combined with religious overtones.

■It served as a center for the training of scholar monks, who studied Buddhist doctrines.

Context

■The name Great Eastern Temple refers to its location on the eastern edge of the city of Nara, Japan (called Daibutuden).

■The temple is noted for its colossal sculpture of seated Vairocana Buddha.

■The temple and Buddha have been razed several times during military unrest.

■The Buddha is influenced by monumental Chinese sculptures (cf. Longmen Caves, Figures 24.9a, 24.9b, 24.9c).

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 197

Great Buddha, base 8th century, upper portion including head 12th century, bronze (Figure 25.1b)

Figure 25.1b: Todai-ji, Great Buddha, base 8th century, upper portion including head 12th century, bronze

■Largest metal statue of Buddha in the world.

■Monumental feat of casting.

■Emperor Shōmu embraced Buddhism and erected sculpture as a way of stabilizing Japanese population during a time of economic crisis.

■Mudra: right hand means “do not fear”; left hand means “welcome.”

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 197

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Images of Buddha Across Asia

– Bamiyan Buddha (Figure 23.2)

– Jowo Rinpoche (Figure 23.3)

– Longmen Caves (Figures 24.9a, 24.9b, 24.9c)

Nio guardian figures, c. 1203, wood, by Unkei (Figures 25.1c and 25.1d)

Figure 25.1c: Nio guardian figure, c. 1203, wood, by Unkei

Figure 25.1d: Nio guardian figure, c. 1203, wood, by Unkei

■They are placed on either side of the Todai-ji south gate.

■The sculptures are a series of complexly joined woodblock pieces.

■Masculine, frightening figures that protect the Buddha derived from Chinese guardian figures such as those at Luoyang.

■Fierce, forbidding looks and gestures.

■Intricate swirling drapery.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 197

Great South Gate, 1181–1203, wood with ceramic tile roofing (Figure 25.1e)

Figure 25.1e: Great South Gate, 1181–1203, wood with ceramic tile roofing

■This is the main gate of Todai-ji.

■Nandaimon: great south gate, with five bays—three central bays for passing and two outer bays that are closed.

■The two stories are the same size: unusual in Japanese architecture (usually the upper story is smaller).

■Deep eaves are supported by the six-stepped bracket complex, which rise in tiers with no bracketed arms.

■The roof is supported by huge pillars.

■Unusual in that it has no ceiling; the roof is exposed from below.

■Overall effect is of proportion and stateliness.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 197

Web Source http://www.todaiji.or.jp/english/

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Entrances

– Great Portal, Chartres (Figure 12.6)

– North Gate of the Great Stupa (Figure 23.4c)

– Front Gate of the Forbidden City (Figure 24.2b)

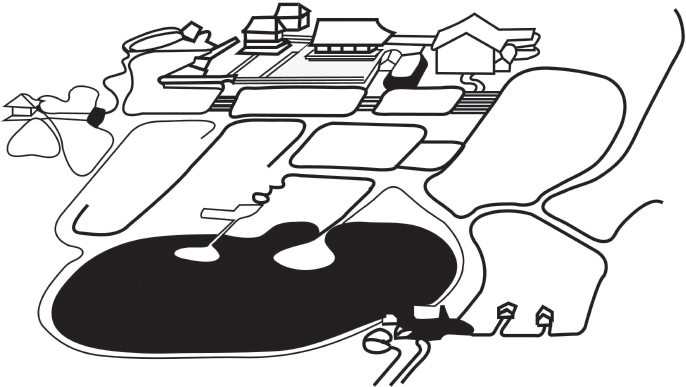

Ryoan-ji, Muromachi period, c. 1480, current design 18th century, rock garden, Kyoto, Japan (Figures 25.2a, 25.2b, 25.2c)

Figure 25.2a: Ryoan-ji, Muromachi period, c. 1480, current design 18th century, wet garden, Kyoto, Japan

Figure 25.2b: Ryoan-ji, dry garden

Figure 25.2c: Ryoan-ji, plan

■Garden as a microcosm of nature.

■Zen dry garden:

–Gravel represents water; gravel is raked in wavy patterns daily by monks.

–Rocks represent mountain ranges.

–Asymmetrical arrangement.

–The garden is bounded on two sides by a low, yellow wall.

–Fifteen rocks arranged in three groups interpreted as:

•Islands in a floating sea.

•Mountain peaks above clouds.

•Constellations in the sky.

•A tiger taking her cubs across a stream.

–Meant to be viewed from a veranda in a nearby building, the abbot’s residence.

–From no viewpoint is the entire garden viewable at once.

–Garden served as a focus for meditation; in a sense, a garden entered by the mind.

■Wet garden:

–Contains a teahouse.

–Seemingly arbitrary in placement, the plants are actually placed in a highly organized and structured environment symbolizing the natural world.

–Water symbolizes purification; used in rituals.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 207

Web Source http://www.ryoanji.jp/smph/eng/

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: People and Nature

–Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds (Figure 29.27)

–Velasco, Valley of Mexico (Figure 21.4)

–Turner, Slave Ship (Figure 20.5)

JAPANESE PAINTING AND PRINTMAKING

Chinese painting techniques and formats were popular in Japan as well, so it is common to see the Japanese as masters of the handscroll, the hanging scroll, and the decorative screen.

Characteristics of the Japanese style include elevated viewpoints, diagonal lines, and depersonalized faces.

A Japanese specialty is haboku or ink-splashed painting that involved applying in a free and open style that gives the illusion of being splashed on the surface. The preponderance of Chinese imagery and painting techniques caused a reaction in Japan, as artists and patrons sought to find a national voice, independent of other Asian traditions. Yamato-e, developed in the twelfth century, features tales from Japanese history and literature depicted usually in long narrative scrolls. There is a depersonalization of figures in yamato-e works, often with just a line to indicate the eyes and mouth, and many times the nose is missing or just suggested. Strong diagonals dominate compositions that feature buildings with their roofs missing so we can see inside. Clouds are used to divide compositions into sections so they become more manageable to the viewer.

Genre painting from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries was dominated by ukiyo-e, a term that means “pictures of the floating world.” The word “floating” is meant in the Buddhist sense of the passing or transient nature of life; therefore ukiyo-e works depict scenes of everyday life or pleasure: festivals, theater (i.e., the kabuki), domestic life, geishas, brothels, and so on. Ukiyo-e is most famously represented in wood-block prints, although it can be found on scrolls and painted screens.

Ukiyo-e was immensely popular; millions of prints were sold to the middle class during its heyday, usually put between 1658 and 1858. Although disdained by the Japanese upper classes for being popular, they won particular affection in Europe and in the Americas as an example of innovative Japanese art.

Printmaking was a collaborative process between the artist and the publisher. The publisher determined the market, dictated the subject matter and style, and employed the woodblock carver and the printer. At first, all prints were in black and white, but the popularity encouraged experimentation, and a two-color system was introduced in 1741.

By 1765, a polychrome print was created, and while this made the product more time-consuming to create and therefore more expensive, it was wildly popular and sold enthusiastically. Colors are subtle and delicate, and separated by black lines. Each color was applied one at a time, requiring a separate step in the printmaking process. This made the steps complicated with precise alignments critical to a successful print. Suzuki Harunobu was the first successful ukiyo-e artist in the polychrome tradition. Hokusai explored the relationship of ukiyo-e and landscape painting.

Western artists were taken with ukiyo-e prints. They particularly enjoyed the flat areas of color, the largely unmodulated tones, the lack of shadows, and the odd compositional angles, with figures occasionally seen from behind. Forms are often unexpectedly cut off and cropped by the frame of the work. The Western interest in realistic subject matter found agreement in ukiyo-e prints.

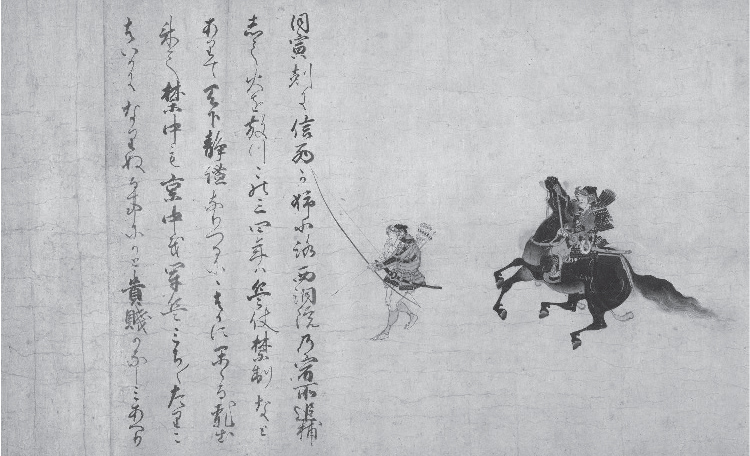

Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Kamakura period, c. 1250–1300, Handscroll (ink and color on paper), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Figures 25.3a and 25.3b)

Figure 25.3a: Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Kamakura period, c. 1250–1300, handscroll (ink and color on paper), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Figure 25.3b: Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, detail

Form

■A narrative work that is read from right to left as the scroll is unrolled.

■Point of view: one looks down from above onto the scene, which takes place in Kyoto.

■Strong diagonals emphasize movement and action.

■Swift, active brushstrokes.

■Depersonalized figures; many with only one stroke for the eyes, ears, and mouth.

■Tangled mass of forms accentuated by Japanese armor.

■Final scene: lone archer leads the escape from the burning palace with the Japanese commander behind him.

Function

■Hand scroll, meant to be read and studied, not meant to be placed on permanent display.

Context

■Military rule in Japan from 1185 on had an interest in the code of the warrior; reflected in the large quantity of war-related literature and paintings.

■Scroll depicts a coup staged in 1159 as Emperor Go-Shirakawa is taken prisoner.

■Burning of the imperial palace at Sanjô in Kyoto as rebel forces try to seize power by capturing a retired emperor.

■Imperial palace in flames; rebels force the emperor to board a cart waiting to take him into captivity.

■Rebels kill those opposed and place their heads on sticks and parade them as trophies.

■Painted a hundred years after the civil war depicted in the scene.

■Unrolls like a film sequence; as one unrolls, time advances.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 203

Web Source http://learn.bowdoin.edu/heijiscroll/

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Historical Events

–Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Figures 29.4a, 29.4b)

–Goya, And There’s Nothing to Be Done (Figure 20.2)

–Column of Trajan (Figure 6.16)

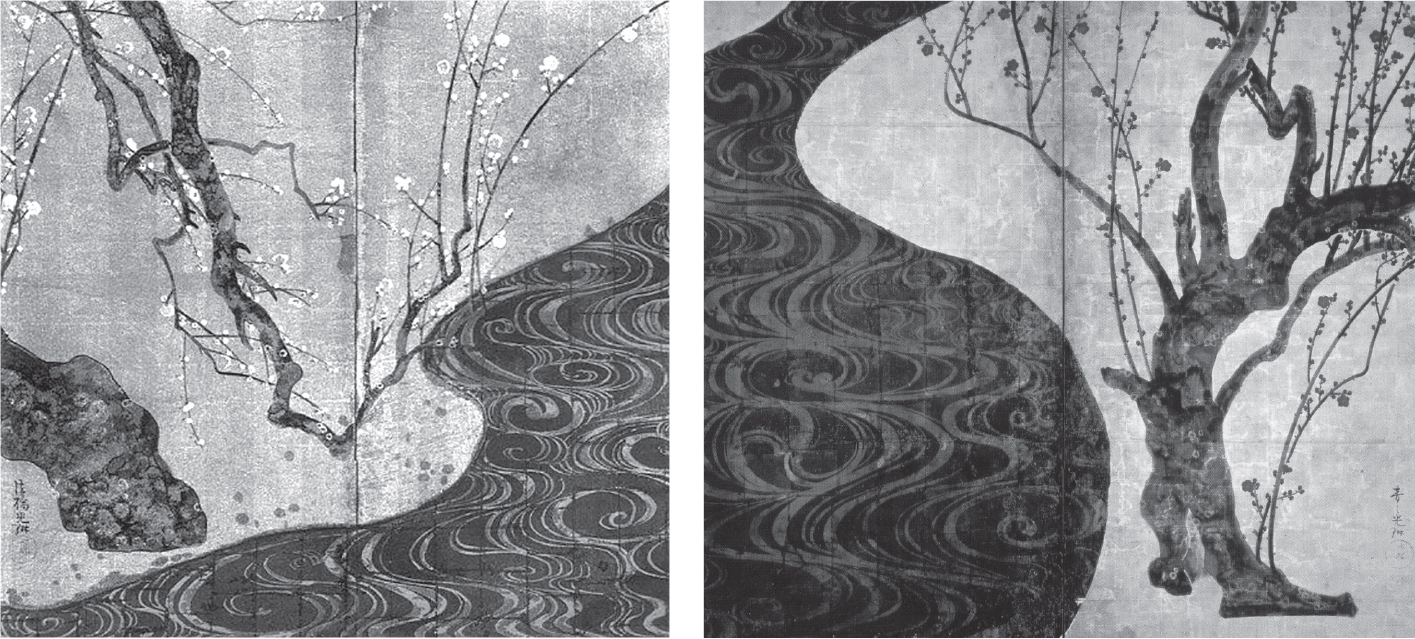

Ogata Korin, White and Red Plum Blossoms, 1710–1716, ink, watercolor, and gold leaf on paper, MOA Museum of Art, Atami, Japan (Figures 25.4a and 25.4b)

Figures 25.4a and 25.4b: Ogata Korin, White and Red Plum Blossoms, 1710–1716, ink, watercolor, and gold leaf on paper, MOA Museum of Art, Atami, Japan

Form

■A stream cuts rhythmically through the scene; swirls in the paint surface indicate water currents.

■White plum blossoms on left; red on right.

■The artist worked in vivid colors or ink monochrome on gold ground.

■This work has more abstracted and simplified forms than the compositions of Ogata’s predecessors.

■Old tree on left is balanced by new tree on right.

Function

■Japanese screen, usually used to separate spaces in a room.

Context

■Japanese rinpa style named for Ogata (Rin, for Ko-rin, and pa, meaning “school”).

■The work is influenced by the yamato-e style of painting.

■Tarashikomi technique, in which paint is applied to a surface that has not already dried from a previous application; creates a dripping effect, useful in depicting streams or flowers.

■The artist was a member of a Kyoto family of textile merchants that serviced samurai, a few nobility, and city dwellers.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 210

Web Source for Rinpa Style http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rinp/hd_rinp.htm

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Multi-Panel Paintings

–Campin, Annunciation Triptych (Figure 14.1)

–Grünewald, Isenheim altarpiece (Figures 14.4a, 14.4b)

–Circle of the Gonzalez family, Screen with the Siege of Belgrade and hunting scene (Figures 18.3a, 18.3b)

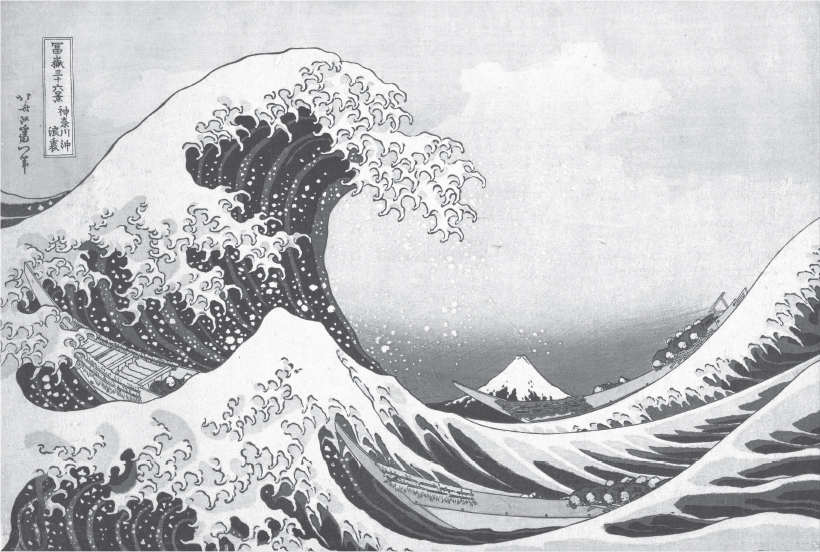

Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), called the Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830–1833, polychrome wood-block print; ink and color on paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Figure 25.5)

Figure 25.5: Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), called the Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830–1833, polychrome wood-block print; ink and color on paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

■Personification of nature; the wave seems intent on drowning the figures in boats.

■Mount Fuji, sacred mountain to the Japanese, seems to be one of the waves.

■The striking design contrasts water and sky with large areas of negative space.

■Imported color: Prussian blue, which made the print seem unusual and special to contemporaries.

Function

■Part of series of prints called Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.

Materials and Techniques

■Each wood-block print required the collaboration of a designer, an engraver, a printer, and a publisher.

■Conceived of as a commercial opportunity by the publisher, who may have doubled as a book dealer.

■The publisher determined the theme.

■The print was designed by an artist on paper, and then an engraver copied the design onto a woodblock.

■The printer rubs ink onto the block and places paper over the block to make a print.

■Many colored prints were made by using a separate block for each color.

■Prussian blue was highly prized in Japan; acquired through trade with Europe.

Context

■Mount Fuji, the highest mountain in Japan, is known for its symmetrical cone.

■Mount Fuji is considered a sacred site.

■In Shintoism, the forces of nature unite as one, as they do in the Hokusai print.

■This was the first time a landscape was a major theme in Japanese prints.

Content Area South, East, and Southeast Asia, Image 211

Web Source http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/JP1847/

■ Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Images of the Sea and Water

–Michelangelo, The Flood (Figure 16.2d)

–Turner, Slave Ship(Figure 20.5)

–Kusama, Narcissus Garden (Figures 22.25a, 22.25b)

VOCABULARY

Continuous narrative: a work of art that contains several scenes of the same story painted or sculpted in continuous succession (Figure 25.3a)

Genre painting: painting in which scenes of everyday life are depicted

Haboku (splashed ink): a monochrome Japanese ink painting done in a free style in which ink seems to be splashed on a surface

Kondo: a hall used for Buddhist teachings (Figure 25.1a)

Mandorla: (Italian, meaning “almond”) a term that describes a large almond-shaped orb around holy figures like Christ and Buddha (Figure 25.1b)

Tarashikomi: a Japanese painting technique in which paint is applied to a surface that has not already dried from a previous application (Figures 25.4a and 25.4b)

Ukiyo-e: translated as “pictures of the floating world,” a Japanese genre painting popular from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century (Figure 25.5)

Yamato-e: a style of Japanese painting that is characterized by native subject matter, stylized features, and thick bright pigments

Zen: a metaphysical branch of Buddhism that teaches fulfillment through self-discipline and intuition

SUMMARY

With much of its tradition intact, a firm history of Japanese artistic production can be studied from its earliest roots. Sculptures often survive in their original architectural settings.

The Japanese are particularly sensitive to the properties of wood construction. The earliest buildings maintain the beauty of untreated wood and show a great emphasis on harmonizing with the natural surrounding environment. Japanese buildings are meant to be viewed as part of an overall balance in nature. Japanese buildings never intrude upon a setting, but complement it fully.

Traditional Chinese forms of painting, such as scrolls, were admired in Japan. Nevertheless, uniquely Japanese artistic styles, such as ukiyo-e prints, were popular as well, particularly with the middle classes. The impact of ukiyo-e prints on nineteenth-century European art cannot be overstated.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.The Nio guardian figures and the Lamassu from the Assyrian culture have in common that they are both

(A)meant to symbolically protect the areas behind them

(B)a combination of human and animal forms

(C)made of stone and symbolize permanence

(D)carved with the image of the ruler on their faces

2.The Great Buddha in Todai-ji’s Great East Temple was probably influenced by similar works, such as

(A)the Terra cotta warriors

(B)Longmen Caves

(C)Angkor Wat

(D)the Great Stupa

3.Japanese wood-block prints can be seen as directly influencing works like Mary Cassatt’s The Coiffure in that they both

(A)share an affinity for brilliant coloring

(B)place figures at odd angles to the picture plane

(C)are concerned with solid modeling and massing of forms

(D)use the conventional three-dimensional linear perspective

4.The yamato-e technique is characterized by

(A)themes taken from Chinese literature

(B)the figures, which are highly individualized with great emphasis on reality

(C)compositions dominated by diagonals

(D)the artists who were the first in Japan to specialize in the Western oil painting technique

5.Dry landscape gardens in Japanese art carry great symbolic value. The viewer was meant to

(A)arrange the rocks and the sand in an artful display to suggest a real landscape

(B)sit directly in the center of the garden and meditate on the natural environment

(C)use the garden as a place to refresh the spirit by painting, writing poetry, or composing music

(D)be refreshed through reflection, contemplation, and meditation

Short Essay

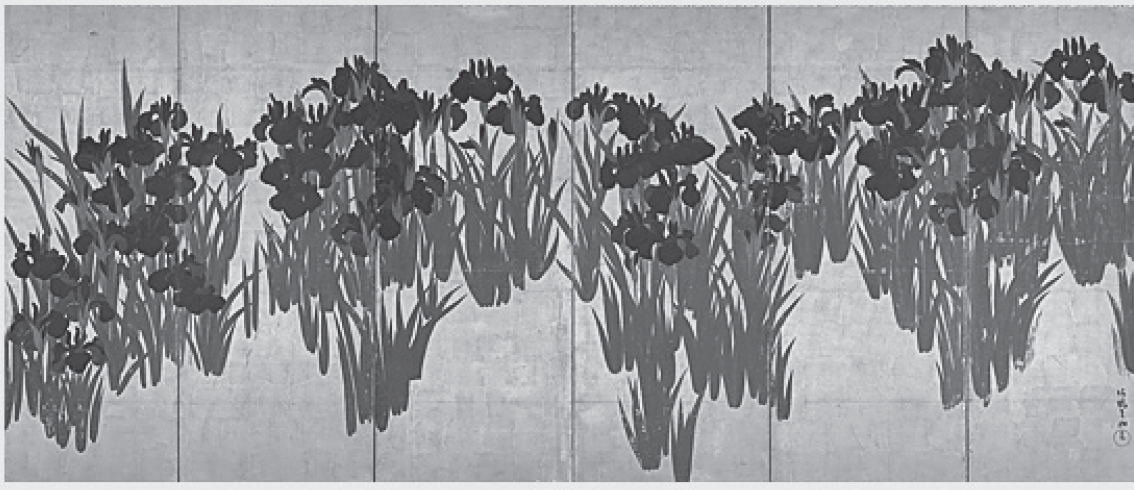

Practice Question 5: Attribution

Suggested Time 15 minutes

Attribute this painting to the artist who painted it.

Using at least two specific details, justify your attribution by describing relevant similarities between this work and a work in the required course content.

Using at least two specific details, explain why these visual elements are characteristic of this artist.

ANSWER KEY

1.A

2.B

3.B

4.C

5.D

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(A)Both the Nio guardian figures and the Lamassu are images at gateways, which act to shield the areas behind them.

2.(B)The grandeur of the Great Buddha in Todai-ji’s Great East Temple is equal to the great Buddha statues at the Longmen Caves.

3.(B)Mary Cassatt’s compositions were influenced by the unusual compositional angles seen in many Japanese wood-block prints.

4.(C)Yamato-e is more about Japanese history and literature depicted with diagonal compositions and depersonalized faces than about oil paint. Yamato-e was developed in Japan in the twelfth century, well before European contact.

5.(D)Viewers never entered a Japanese dry garden. They were enclosed environments meant for reflection, contemplation, and meditation.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Attribute this painting to the artist who painted it. |

1 |

Ogata Korin |

Using at least two specific details, justify your attribution by describing relevant similarities between this work and a work in the required course content. |

2 |

The work in the required course content is White and Red Plum Blossoms by Ogata Korin, 1710–1716, watercolor on paper. Two specific details could include: ■Diagonals influenced by the yamato-e style of painting. ■Rhythmic composition. ■Painted on a screen. ■View limited to a few details that are carefully painted rather than grand, detailed landscapes. ■Tarashikomi technique in which paint is applied to a surface that has not already dried from a previous application; creates a dripping effect useful in depicting streams and flowers. |

Using at least two specific details, explain why these visual elements are characteristic of this artist. |

2 |

Answers could include Ogata Korin’s belief in: ■Concentrating on a few details. ■A deeply personal view of nature. ■An emphasis on a fragile, tender, and gentle—rather than an awesome, threatening, or overwhelming—nature. ■Organizing natural forms into patterned compositions. |