Content Area: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 C.E.

Early Renaissance in Italy: Fifteenth Century

TIME PERIOD: 1400–1500

The Early Renaissance takes place in the courts of Italian city-states: Ferrara, Florence, Mantua, Naples, Rome, Venice, and so on.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Donatello, David)

Essential Knowledge:

■Renaissance art is generally the art of Western Europe.

■Renaissance art is influenced by the art of the classical world, Christianity, a greater respect for naturalism, and formal artistic training.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction.

Essential Knowledge:

■There are the beginnings of global commercial and artistic networks.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art making is influenced by available materials and processes.

Learning Objective: Discuss how material, processes, and techniques influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Donatello, David)

Essential Knowledge:

■The period is dominated by an experimentation of visual elements, i.e., atmospheric perspective, a bold use of color, creative compositions, and an illusion of naturalism.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Botticelli, Birth of Venus)

Essential Knowledge:

■There is a more pronounced identity of the artist in society; the artist has more structured training opportunities.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence.

Essential Knowledge:

■Renaissance art is studied in chronological order.

■There is a large body of primary source material housed in libraries and public institutions.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Italian city-states were controlled by ruling families who dominated politics throughout the fifteenth century. These princes were lavish spenders on the arts, and great connoisseurs of cutting-edge movements in painting and sculpture. Indeed, they embellished their palaces with the latest innovative paintings by artists such as Lippi and Botticelli. They commissioned architectural works from the most pioneering architects of the day. Competition among families and city-states encouraged a competition in the arts, each state and family seeking to outdo the other.

Princely courts gradually turned their attention away from religious subjects to more secular concerns, in a spirit today defined as humanism. It became acceptable, in fact encouraged, to explore Italy’s pagan past as a way of shedding light on contemporary life. The exploration of new worlds, epitomized by the great European explorers, was mirrored in a new growth and appreciation of the sciences, as well as the arts.

Patronage and Artistic Life

The influence of the patrons of this period can be seen in a number of ways, including such things as specifying the amount of gold lavished on an altarpiece or which family members the artist was required to prominently place in the foreground of a painting. It was also customary for great families to have a private chapel in the local church dedicated to their use. Artists would often be asked to paint murals in these chapels to enhance the spirituality of the location.

EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE

Renaissance architecture depends on order, clarity, and light. The darkness and mystery, indeed the sacred sense of Gothic cathedrals, was deemed barbaric. In its place were created buildings with wide window spaces, limited stained glass, and vivid wall paintings.

Although all buildings need mathematics to sustain the engineering principles inherent in their design, Renaissance buildings seem to stress geometric designs more demonstrably than most. Harmonies were achieved by a system of ideal proportions learned from an architectural treatise by the Roman Vitruvius. The ratios and proportions of various elements of the interior of Florentine Renaissance churches were interpreted as expressions of humanistic ideals. The Early Christian past was recalled in the use of unvaulted naves with coffered ceilings.

Thus, the crossing is twice the size of the nave bays, the nave twice the width of the side aisles, and the side aisles twice the size of side chapels. Arches and columns take up two-thirds of the height of the nave, and so on. This logical expression is often strongly delineated by the floor patterns in the nave, in which white and gray marble lines demarcate the spaces, as at Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel (Figures 15.1a and 15.1b).

Florentine palaces, such as Alberti’s Palazzo Rucellai (Figure 15.2), have austere dominating façades that rise three stories from street level. Usually the first floor is reserved as public areas; business is regularly transacted here. The second floor rises in lightness, with a strong stringcourse marking the ceiling of one story and the floor of another. The third floor is capped by a heavy cornice in the style of a number of Roman temples.

Filippo Brunelleschi, Pazzi Chapel, Basilica di Santa Croce, designed 1423, built 1429–1461, masonry, Florence, Italy (Figures 15.1a and 15.1b)

Form

■Two barrel vaults on the interior; small dome over crossing; pendentives support dome; oculus in the center.

■Interior has a quiet sense of color with muted tones that is punctuated by glazed terra cotta tiles.

■Use of pietra serena (a grayish stone) in contrast to whitewashed walls accentuates basic design structure.

■Inspired by Roman triumphal arches.

■Ideal geometry in the plan of the building.

Function

■Chapter house: a meeting place for Franciscan monks; bench that wraps around the interior provides seating for meetings.

■Rectangular chapel with an apse and an altar attached to the church of Santa Croce, Florence.

Attribution

■Attribution of portico by Brunelleschi has been recently questioned; the building may have been designed by Bernardo Rossellino or his workshop.

Patronage

■Patrons were the wealthy Pazzi family, who were rivals of the Medici.

■The family coat-of-arms, two outward facing dolphins, is placed at the base of each pendentive on the interior.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 67

Web Source http://www.sgira.org/hm/brun7.htm

Figure 15.1a: Filippo Brunelleschi, Pazzi Chapel, Basilica di Santa Croce, 1429–1461, masonry, Florence, Italy

Figure 15.1b: Filippo Brunelleschi, Pazzi Chapel interior, Basilica di Santa Croce, 1429–1461, masonry, Florence, Italy

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Personal Sacred Spaces

–Bernini, Cornaro Chapel (Figures 17.4a, 17.4b)

–Giotto, Arena Chapel (Figures 13.1a, 13.1b, 13.1c)

–Ryoan-ji (Figures 25.2a, 25.2b)

Leon Battista Alberti, Palazzo Rucellai, c. 1450, stone, masonry, Florence, Italy (Figure 15.2)

Form

■Three horizontal floors separated by a strongly articulated stringcourse; each floor is shorter than the one below.

■Pilasters rise vertically and divide the spaces into squarish shapes.

■An emphasized cornice caps the building.

■Square windows on the first floor; windows with mullions on the second and third floors.

■Rejects rustication of earlier Renaissance palaces; used beveled masonry joints instead.

■Benches on lower level connect the palazzo with the city.

Figure 15.2: Leon Battista Alberti, Palazzo Rucellai, c. 1450, stone, masonry, Florence, Italy

Function

■City residence of the Rucellai family.

■The building format expresses classical humanist ideals for a residence: the bottom floor was used for business; the family received guests on the second floor; the family’s private quarters were on the third floor; the hidden fourth floor was for servants.

Context

■The articulation of the three stories links the building to the Colosseum levels, which have arches framed by columns: the first floor pilasters are Tuscan (derived from Doric); the second are Alberti’s own invention (derived from Ionic); the third are Corinthian.

■Original building:

–Five bays on the left, with a central door.

–Second doorway bay and right bay added later.

–Eighth bay fragmentary: owners of house next door refused to sell, and the Palazzo Rucellai never expanded.

Patronage

■Patron was Giovanni Rucellai, a wealthy merchant.

■Rucellai coat-of-arms, a rampart lion, is placed over two second-floor windows.

■Friezes contain Rucellai family symbols: billowing sails.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 70

Web Source http://www.sgira.org/hm/alberti3.htm

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Buildings in Urban Spaces

–Gehry, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (Figures 29.1a, 29.1b)

–Sullivan, Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building (Figure 21.14a)

–Trajan’s Market (Figure 6.10a)

FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE

The most characteristic development of Italian Renaissance painting is the use of linear perspective, a technique some scholars say was known to the Romans. Other scholars have attributed its revitalization, if not invention, to Filippo Brunelleschi, who developed perspective while drawing the Florence Cathedral Baptistery in the early fifteenth century. Some artists were fascinated with perspective, showing objects and people in proportion with one another, unlike medieval art which has people dominating compositions. Artists who were trained prior to this tradition were quick to see the advantages to linear perspective and incorporated it into their later works.

Later in the century, perspective becomes an instrument that some artists would use, or exploit, to create different artistic effects. The use of perspective to intentionally fool the eye, the trompe l’oeil technique, is an outgrowth of the ability of later fifteenth-century painters who employed it as one tool in an arsenal of techniques.

In the early part of the fifteenth century, religious paintings dominated, but by the end of the century, portraits and mythological scenes proliferated, reflecting humanist ideals and aspirations.

Interest in humanism and the rebirth of Greco-Roman classics also spurs an interest in authentic Greek and Roman sculptures. The ancients gloried in the nude form in a way that was interpreted by medieval artists as pagan. The revival of nudity in life-size sculpture is begun in Florence with Donatello’s David (Figure 15.5), and continued throughout the century.

Nudity is one manifestation of an increased study of human anatomy. Drawings of people with heroic bodies are sketched in the nude and transferred into stone and bronze. Some artists show the intense physical interaction of forms in the twisting gestures and straining muscles of their works.

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child with Two Angels, c. 1465, tempera on wood, Uffizi, Florence (Figure 15.3)

Content and Symbolism

■Symbolic landscape

–Rock formations symbolize the Christian Church.

–City near the Madonna’s head is the Heavenly Jerusalem.

■Pearl motif: seen in headdress and pillow as products of the sea (in upper-left corner).

■Pearls used as symbols in scenes of the Incarnation of Christ.

Context

■Mary seen as a young mother.

■Model may have been the artist’s lover.

■Landscape inspired by Flemish painting.

■Scene depicted as if in a window in a Florentine home.

■Humanization of a sacred theme; there is a sense of domestic intimacy.

■Lippi was a monk, as indicated by the word “Fra” that precedes his name; he was working in a Carmelite monastery under the patronage of the Medici.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 71

Web Source https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2004/feb/14/art

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Virgin Mary

–Notre Dame de la Belle Verriere (Figure 12.8)

–Röttgen Pietà (Figure 12.7)

–Miguel González, Virgin of Guadalupe (Figure 18.4)

Figure 15.3: Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child with Two Angels, c. 1465, tempera on wood, Uffizi, Florence

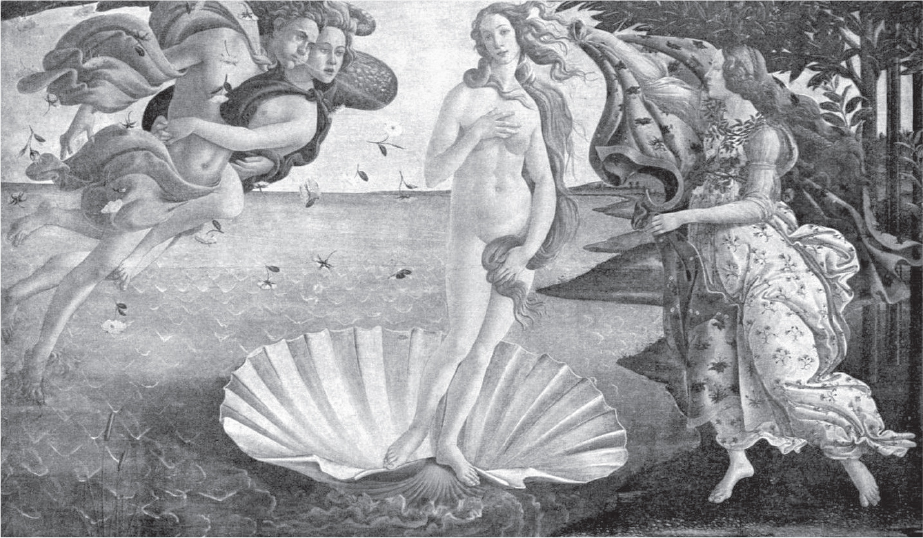

Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, c. 1484–1486, tempera on canvas, Uffizi, Florence (Figure 15.4)

Form

■Crisply drawn figures.

■Landscape flat and unrealistic; simple V-shaped waves.

■Figures float, not anchored to the ground.

Content

■Venus emerges fully grown from the foam of the sea with a faraway look in her eyes.

■Roses scattered before her; roses created at the same time as Venus, symbolizing that love can be painful.

■On the left: Zephyr (west wind) and Chloris (nymph).

■On the right: handmaiden rushes to clothe Venus.

Context

■Medici commission; may have been commissioned for a wedding celebration.

■Painting based on a popular court poem by the writer Poliziano, which itself is based on Homeric hymns and Hesiod’s Theogony.

■A revival of interest in Greek and Roman themes can be seen in this work.

■Earliest full-scale nude of Venus in the Renaissance.

■Reflects emerging Neoplatonic thought.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 72

Web Source http://www.pbs.org/empires/medici/renaissance/botticelli.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Classical References

–David, The Oath of the Horatii (Figure 19.6)

–Raphael, School of Athens (Figure 16.3)

–Dürer, Adam and Eve (Figure 14.3)

Figure 15.4: Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, c. 1484–1486, tempera on canvas, Uffizi, Florence

Donatello, David, c. 1440–1460, bronze, National Museum, Bargello, Florence (Figure 15.5)

Form

■First large bronze nude since antiquity.

■Exaggerated contrapposto of the body.

■Sleekness of the black bronze adds to the femininity of the work.

■Androgynous figure; homoerotic overtones.

Function

■Life-size work, probably meant to be housed in the Medici palace courtyard; not for public viewing.

Content

■The work depicts the moment after David slays the Philistine Goliath with a rock from a slingshot; David then decapitates Goliath with his own sword (1 Samuel 17).

■David contemplates his victory over Goliath, whose head is at his feet; David’s head is lowered to suggest humility.

■Laurel on David’s hat indicates he was a poet; the hat is a foppish Renaissance design.

Figure 15.5: Donatello, David, c. 1440–1460, bronze, National Museum, Bargello, Florence

Context

■David symbolizes Florence taking on larger forces with ease; perhaps Goliath would have been equated with the Duke of Milan.

■Nothing is known of its commission or patron, but it was placed in the courtyard of the Medici palace in Florence.

■Modern theory alleges that this is a figure of Mercury, and that the decapitated head is of Argo; Mercury is the patron of the arts and merchants, and therefore an appropriate symbol for the Medici.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 69

Web Source http://www.pbs.org/empires/medici/renaissance/donatello.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Nudity

–Female deity from Nukuoro (Figure 28.2)

–Seated boxer (Figure 4.10)

–Ingres, La Grande Odalisque (Figure 20.3)

VOCABULARY

Bottega: the studio of an Italian artist

Chapter house: a building next to a church used for meetings (Figures 15.1a and 15.1b)

Humanism: an intellectual movement in the Renaissance that emphasized the secular alongside the religious. Humanists were greatly attracted to the achievements of the classical past, and stressed the study of classical literature, history, philosophy, and art

Madonna: the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus Christ (Figure 15.3)

Mullion: a central post or column that is a support element in a window or a door (Figure 15.2)

Neoplatonism: a school of ancient Greek philosophy that was revived by Italian humanists of the Renaissance

Orthogonal: lines that appear to recede toward a vanishing point in a painting with linear perspective

Perspective: depth and recession in a painting or a relief sculpture. Objects shown in linear perspective achieve a three-dimensionality in the two-dimensional world of the picture plane. Lines, called orthogonals, draw the viewer back in space to a common point, called the vanishing point. Paintings, however, may have more than one vanishing point, with the orthogonals leading the eye to several parts of the work. Landscapes that give the illusion of distance are in an atmospheric or aerial perspective.

Pietra serena: a dark-gray stone used for columns, arches, and trim details in Renaissance buildings (Figure 15.1b)

Pilaster: a flattened column attached to a wall with a capital, a shaft, and a base (Figure 15.2)

Quattrocento: the 1400s, or fifteenth century, in Italian art

Trompe l’oeil: (French, meaning “fools the eye”) a form of painting that attempts to represent an object as existing in three dimensions, and therefore resembles the real thing

SUMMARY

Humanist courts of Renaissance Italy patronized artists who rendered both religious compositions and secular works. After 1450 it is common to see contemporary events, ancient mythology, or portraits of significant people take their place side by side with scenes of the Annunciation and Crucifixion.

Brunelleschi’s development of one-point perspective revolutionized Italian painting. At first, artists faithfully used the formula in their compositions, creating realistic three-dimensional spaces on their surfaces. Later, painters used perspective as a tool to manipulate the viewer’s impression of a particular scene.

Sculptors competed with the glory of ancient artists by creating monumental figures and equestrian images, and revived antiquity’s interest in nudity and idealized human proportion.

Architecture was dominated by spatial harmony and light interiors that contrasted markedly with the mystical stained-glass-filled Gothic buildings.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.Leon Battista Alberti’s architectural style represents a scholarly interpretation of classical elements seen in buildings such as

(A)the Mortuary temple of Hatshepsut

(B)the Parthenon

(C)the Column of Trajan

(D)the Colosseum

Questions 2–4 refer to the following picture.

2.The nudity in Donatello’s David

(A)would have been considered heroic in Islamic art

(B)is inspired by Gothic portal sculpture

(C)references the ideal human proportions expressed in Polykleitos’s canon

(D)recalls the nudity of public sculptures from the ancient Mediterranean

3.The laurel wreath on the head of the David refers to his

(A)oneness with nature

(B)victory over Goliath

(C)role as a shepherd

(D)author of a book in the Bible

4.Before the creation of Donatello’s David, large, public nude sculptures were not executed because

(A)they represented the pagan world of mythological gods

(B)artists were influenced by a general ban on images in Jewish art

(C)they showed man in a primitive and bestial state

(D)they were not suitable for women to view

5.Fra Filippo Lippi’s Madonna and Child with Two Angels reflects the Renaissance’s attitude toward a more

(A)ethereal and heavenly vision of Mary and Jesus

(B)formal and forbidding image of divine figures

(C)human and approachable interpretation of heavenly figures

(D)pagan and mythological approach to Christian imagery

Long Essay

Practice Question 2: Visual and Contextual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

This work is Leon Battista Alberti’s Palazzo Rucellai built c. 1450 of stone and masonry in Florence, Italy. It is a domestic structure.

Select and completely identify another building that is a domestic structure either from the suggested list below or any other relevant work.

Explain how each architect designed his or her building in relationship to the site around it.

In your answer, make sure to:

■Accurately identify the work you have chosen with at least two identifiers beyond those given.

■Respond to the question with an art historically defensible thesis statement.

■Support your claim with at least two examples of visual and/or contextual evidence.

■Explain how the evidence that you have supplied supports your thesis.

■Use your evidence to corroborate or modify your thesis.

Villa Savoye

House in New Castle County

Fallingwater

ANSWER KEY

1.D

2.D

3.D

4.A

5.C

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(D) The three floors with rounded arches interspersed by columns recalls an arrangement on the Colosseum in Rome.

2.(D) Greek and Roman cities are often characterized by a preponderance of large-scale heroic nude figures. Islamic art would have considered nudes as blasphemous and debasing. Gothic portal sculptures are typically entirely covered by drapery except for the extremities. This work does not have the ideal human proportions expressed by Polykleitos.

3.(D) David was a poet. The Book of Psalms is ascribed to his authorship.

4.(A) Nudity was associated with the pagan world; Christians sought to avoid association with pagan gods.

5.(C) The Renaissance was mostly interested in making human the divine image. This painting has a particularly affectionate view of a young mother as Mary, and a suitably human child accompanied by impish angels.

Long Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

Accurately identify the work you have chosen with at least two identifiers beyond those given. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye, 1929, steel and reinforced concrete, Poissy-sur-Seine, France. ■Venturi, Rauch, and Brown, House in New Castle County, 1978–1983, wood frame and stucco, Delaware. ■Wright, Fallingwater, 1936–1939, reinforced concrete, sandstone, steel, and glass, Pennsylvania. |

Respond to the question with an art historically defensible thesis statement. |

1 |

The thesis statement must be an art historically sound claim that responds to the question and does not merely restate it. The thesis statement should come at the beginning of the argument and be at least one, preferably two sentences. For example, the Palazzo Rucellai and Fallingwater are both works that consider aspects of the surrounding environment into their designs. In the first case, the Palazzo Rucellai is in an urban environment, the building constructed downtown amid other buildings; in the second case, Fallingwater is designed in a rural setting with many natural features. |

Support your claim with at least two examples of visual and/or contextual evidence. |

2 |

Two visual or contextual examples are needed here. For these examples, part of the evidence could involve a discussion of the relationship of each work to the area around it. For example, the Palazzo Rucellai is meant to be imposing and symbolize the status of the family who lives there, and to advertise itself to fellow city dwellers. This status is suggested by the friezes that contain the Rucellai family symbols of a billowing sail, or their coat-of-arms. These symbols are meant to impress fellow citydwellers of the status of the family within. |

Explain how the evidence that you have supplied supports your thesis. |

1 |

Good responses link the evidence you have provided with the main thesis statement. For example, make sure you make a strong connection between aspects of the site (the waterfall, for example, in Fallingwater) with the respect for nature felt by the Kaufmanns and Wright, and the welcoming of nature into the home. |

Use your evidence to corroborate or modify your thesis. |

1 |

This point is earned when a student demonstrates a depth of understanding, in this case of domestic architecture. The student must demonstrate multiple insights on a given subject. For example, the student could discuss each building’s function as a home as well as a monument to its owners. |