Content Area: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 C.E.

TIME PERIOD: 200–500 C.E.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The culture, beliefs, and physical settings of a region play an important role in the creation, subject matter, and siting of works of art.

Learning Objective: Discuss how the culture, beliefs, or physical setting can influence the making of a work of art. (For example: Catacomb of Priscilla)

Essential Knowledge:

■Late Antique art falls within the medieval artistic tradition.

■Late Antique art is influenced by the needs of Christian worship.

■Late Antique art is known for its avoidance of naturalistic forms.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Cultural interaction through war, trade, and travel can influence art and art making.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art are influenced by cultural interaction. (For example: Santa Sabina)

Essential Knowledge:

■Late Antique art is heavily influenced by ancient art forms.

■Late Antique art has many regional variations.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art and art making can be influenced by a variety of concerns including audience, function, and patron.

Learning Objective: Discuss how art can be influenced by audience, function, and/or patron. (For example: Santa Sabina)

Essential Knowledge:

■Connections with the divine are illustrated through iconography.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Art history is best understood through an evolving tradition of theories and interpretations.

Learning Objective: Discuss how works of art have had an evolving interpretation based on visual analysis and interdisciplinary evidence. (For example: Orant fresco)

Essential Knowledge:

■Late Antique art is generally studied chronologically.

■Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Christianity, in the first century C.E., was founded by Jesus Christ, whose energetic preaching and mesmerizing message encouraged devoted followers like Saints Peter and Paul to spread the message of Christian faith and forgiveness across the Roman world through active missionary work. Influential books and letters, which today make up the New Testament, were powerful tools that fired the imagination of everyone from the peasant to the philosopher.

Literally an underground religion, Christianity had to hide in the corners of the Roman Empire to escape harsh persecutions, but the number of converts could not be denied, and gradually the Christians became a majority. With Constantine’s triumph at the Milvian Bridge in 312 C.E. came the Peace of the Church. Constantine granted restitution to Christians of state-confiscated property in the 313 C.E. Edict of Milan, which also granted religious toleration throughout the Empire. Constantine also favored Christians for government positions and constructed a series of religious buildings honoring Christian sites. Christianity was well on its way to becoming a state religion, with Emperor Constantine’s blessing.

After emerging from the shadows, Christians began to build churches of considerable merit to rival the accomplishments of pagan Rome. However, pagan beliefs were by no means eradicated by the stroke of a pen, and ironically paganism took its turn as an underground religion in the Late Antique period.

Patronage and Artistic Life

It was not easy being a Christian in the first through third centuries. Persecutions were frequent; most of the early popes, including Saint Peter, were martyred. Those artists who preferred working for the more lucrative official government were blessed with great commissions in public places. Those who worked for Christians had to be satisfied with private church houses and burial chambers.

Most Christian art in the early centuries survives in the catacombs, buried beneath the city of Rome and other places scattered throughout the Empire. Christians were mostly poor—society’s underclass. Artists imitated Roman works, but sometimes in a sketchy and unsophisticated manner. Once Christianity became recognized as an official religion, however, the doors of patronage sprang open. Christian artists then took their place alongside their pagan colleagues, eventually supplanting them.

EARLY CHRISTIAN ART

Christianity is an intensely narrative religion deriving its images from the various books of the New Testament. Christians were also inspired by parallel stories from the Old Testament or Hebrew Scriptures, and they illustrated these to complement Christian ideology. Since there are no written accounts of what the men and women of the Bible looked like, artists recreated the episodes by relying on their imagination. The following episodes from the New Testament are most often depicted:

■The Annunciation: The Angel Gabriel announces to Mary that she will be the virgin mother of Jesus (Figure 14.1).

■The Visitation: Mary visits her cousin Elizabeth to tell her the news that she is pregnant with Jesus. Because she is elderly, Elizabeth’s announcement of her own pregnancy is greeted as a miracle. Elizabeth gives birth to Saint John the Baptist.

■Christmas or the Nativity: The birth of Jesus in Bethlehem. Mary gives birth in a stable; her husband, Joseph, is her sole companion. Soon after, angels announce the birth to shepherds.

■Adoration of the Magi: Traditionally, three kings, who are also astrologers, are attracted by a star that shines over Jesus’s manger. They come to worship him and present gifts.

■Massacre of the Innocents: After Jesus is born, King Herod issues an order to execute all male infants in the hope of killing him. His family takes him to safety in an episode called The Flight into Egypt.

■Baptism of Jesus: John the Baptist, Jesus’s cousin, baptizes him in the Jordan River. Jesus’s ministry officially begins.

■Calling of the Apostles: Jesus gathers his followers, including Saint Matthew and Saint Peter, as his ministry moves forward (Figure 17.5).

■Miracles: To prove his divinity, Jesus performs a number of miracles, like multiplying loaves and fishes, resurrecting the deceased Lazarus, and changing water into wine at the Wedding at Cana.

■Giving the Keys: Sensing his own death, Jesus gives Saint Peter the keys to the kingdom of heaven, in effect installing him as the leader when he is gone, and therefore the first pope.

■Transfiguration: Jesus transfigures himself into God before the eyes of his apostles; this is the high point of his ministry.

■Palm Sunday: Jesus enters Jerusalem in triumph, greeted by throngs with palm branches.

■Last Supper: Before Jesus is arrested, he has a final meal with his disciples in which he institutes the Eucharist—that is, his body and blood in the form of bread and wine; at this meal he reveals that he knows that one of his apostles, Judas, has betrayed him for 30 pieces of silver (Figure 16.1).

■Crucifixion: After a brief series of trials, Jesus is sentenced to death for sedition. He is crowned with thorns, whipped with lashes, and forced to carry his cross through the streets of Jerusalem. At the top of a hill called Golgotha he is nailed to the cross and left to die (Figure 14.4a).

■Deposition/Lamentation/Entombment/Pieta: Jesus’s body is removed from the cross by his relatives, cleaned, mourned over, and buried (Figures 12.7, 13.1, and 16.5).

■Resurrection: On Easter Sunday, three days later, Jesus rises from the dead. On Ascension Day he goes to heaven.

Also important are four author portraits of the Evangelists, who are the writers of the principal books, or gospels, of the New Testament. These books are arranged in the order in which it was traditionally believed they were written: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Evangelist portraits appear often in medieval and Renaissance art, each associated with an attribute:

■Matthew: angel or a man

■Mark: lion

■Luke: ox or calf (Figure 10.2b)

■John: eagle

These attributes derive from the Bible (Ezekiel 1:5–14; Revelations 4:6–8) and were assigned to the four evangelists by great philosophers of the early church such as Saint Jerome.

Catacomb paintings, like the ones at Priscilla (Figure 7.1) from the fourth century, show a sensitivity toward artistic programs rather than random images. Jesus always maintains a position of centrality and dominance, but grouped around him are images that are carefully chosen either as Old Testament prefigurings or as subsidiary New Testament events. Early Christians learned from ancient paintings to frame figures in either lunettes or niches.

When Christianity was recognized as the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380 C.E., Christ was no longer depicted as the humble Good Shepherd; instead he took on imperial imagery. His robes become the imperial purple and gold, his crook a staff, his halo a symbol of the sun-king.

Unlike Roman mosaics, which are made of rock, Christian mosaics are often of gold or precious materials and faced with glass. Christian mosaics glimmer with the flickering of mysterious candlelight to create an other-worldly effect.

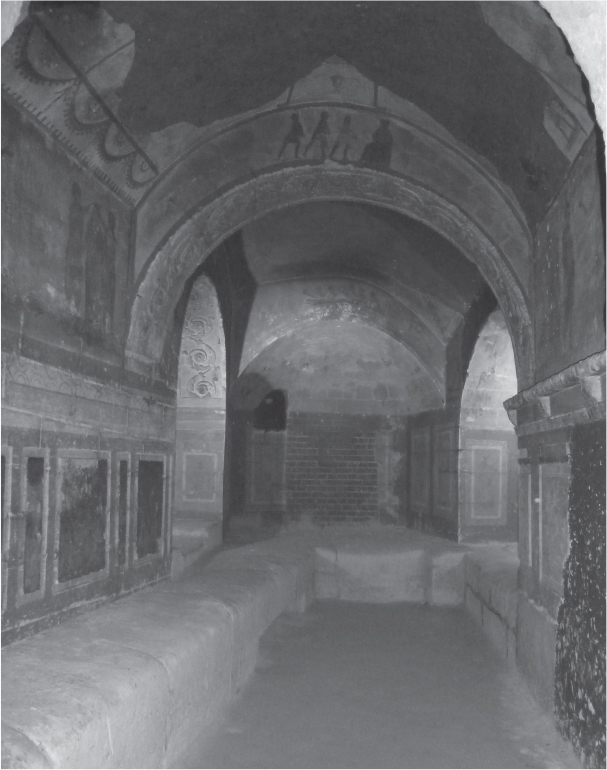

Figure 7.1a: Greek Chapel in the Catacomb of Priscilla, Late Antique Europe, 200–400, excavated tufa and fresco, Rome, Italy

Catacomb of Priscilla, Late Antique Europe, 200–400, excavated tufa and fresco, Rome, Italy (Figures 7.1a, 7.1b, 7.1c)

Form and Function

■Catacombs are passageways beneath Rome that extend for about 100 miles and contain the tombs of 4 million dead.

■They contain the tombs of seven popes and many early Christian martyrs.

■The Priscilla catacomb has some 40,000 burials.

Figure 7.1b: Orant fresco in the Catacomb of Priscilla, 200–400, excavated tufa and fresco, Rome, Italy

Context

■Called Priscilla because she was the donor of the land for her family’s burial. It was then opened up to Christians.

■Greek Chapel (Figure 7.1a):

–Named for two Greek inscriptions painted on the right niche.

–Three niches for sarcophagi.

–Lower portions done in the first Pompeian style of painting with imitation marble paneling enriching the surface.

–Upper portions decorated with paintings in later Pompeian styles: sketchy painterly brushstrokes.

–Contains scenes of Old and New Testament stories.

•Old Testament scenes show martyrs sacrificing for their faith.

•New Testament scenes show miracles of Jesus.

■Orant fresco (Figure 7.1b):

–Fresco over a tomb niche set over an arched wall; cemetery of a family vault.

–Central figure stands with arms outstretched in prayer; perhaps the same woman seen three times.

•Figure is compact, dark, and set off from a light background with terse angular contours and emphatic gestures.

•Figure prays for salvation in heaven.

•Deeply set eyes—windows to the soul—staring upward implore God’s deliverance.

–Left: painting of a teacher with children, or the image of a couple being married with a bishop.

–Right: mother and child, perhaps Mary with Christ or the Church.

Figure 7.1c: Good Shepherd fresco in the Catacomb of Priscilla, 200–400, excavated tufa and fresco, Rome, Italy

■Good Shepherd fresco (Figure 7.1c):

–Parallels between Old and New Testament stories feature prominently in Early Christian art; Christians see this as a fulfillment of the Hebrew scriptures; shows Christian interest in adapting aspects of the Hebrew scriptures in their own context.

–Restrained portrait of Christ as a Good Shepherd, a pastoral motif in ancient art going back to the Greeks.

•Symbolism of the Good Shepherd: rescues individual sinners in his flock who stray.

–Stories of the life of the Old Testament Prophet Jonah often appear in the lunettes; Jonah’s regurgitation from the mouth of a big fish is seen as prefiguring Christ’s resurrection.

–Peacocks in lunettes symbolize eternal life; quails symbolize earthly life; Christ is seen as a bridge between these worlds.

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 48

Web Source http://www.catacombepriscilla.com/index_en.html

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ceiling paintings

–Sistine Chapel ceiling (Figure 16.2a)

–Gaulli, Triumph of the Name of Jesus (Figure 17.6)

EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE

Under the city of Rome can be found a hundred miles of catacombs, sometimes five stories deep, with millions of interred bodies. Christians, Jews, and pagans used these burial grounds because they found this a cheaper alternative to aboveground interment. Finding the Roman practice of cremation repugnant, Christians preferred burial because it symbolized Jesus’s, as well as their own, rising from the dead—body and soul.

Catacombs were dug from the earth in a maze of passageways that radiated out endlessly from the starting point. The poor were placed in loculi, which were holes cut in the walls of the catacombs meant to receive the bodies of the dead. Usually the bodies were folded over to take up less room. The wealthy had their bodies blessed in mortuary chapels, called cubicula, and then often placed in extravagant sarcophagi.

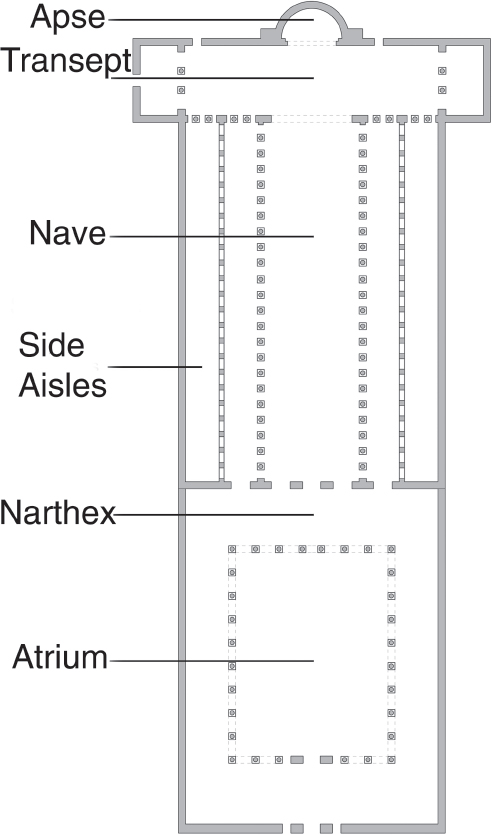

After the Peace of the Church in 313 C.E., Christians understood how they could adapt Roman architecture to their use. Basilicas, with their large, groin-vaulted interiors and impressive naves, were meeting places for the influential under the watchful gaze of the emperor’s statue. Christians reordered the basilica, turning the entrance to face the far end instead of the side, and focused attention directly on the priest, whose altar (meaning “high place”) was elevated in the apse. The clergy occupied the perpendicular aisle next to the apse, called the transept. Male worshippers stood in the long main aisle called the nave; females stood in the side aisles with partial views of the ceremony. In this way, Christians were inspired by Jewish communities in which this gender division was standard.

Figure 7.2: Early Christian basilica. Some basilicas do not have a transept and have only one side aisle on either side of the nave.

A narthex, or vestibule, was positioned as a transitional zone in the front of the church. An atrium was constructed in front of the building, framing the façade. Atria also housed the catechumens, those who expressed a desire to convert to Christianity but had not yet gone through the initiation rites. They were at once inside the church precincts but outside the main building. On occasion this overall design had the symbolic effect of turning the church into a cross shape.

Early Christian art has a “love/hate” relationship with its Roman predecessors. On the one hand, these were the people who mercilessly cemented Christians into giant flowerpots, covered them with tar, ignited them, and used them to light the streets at night. On the other hand, this was the world they knew: the grandeur, the excitement, the eternal quality suggested by mythical Rome.

Early Christian art shows an adaptation of Roman elements—taking from their predecessors the ideas that best expressed Christianity, and using the remnants of their monuments to embellish the new faith. In this way, Christianity, like most religions, expressed dominance over the older forms of worship by forcing pagan architectural elements, like columns, to do service to a new faith. Santa Sabina (Figures 7.3a, 7.3b, and 7.3c) employed a number of Roman columns from pagan temples. This type of reuse of architectural or sculptural elements is called spolia.

Early Christian churches come in two types, both inspired by Roman architecture: centrally planned and axially planned buildings. The exteriors of both church structures avoided decoration and sculpture that recall the façade of pagan temples.

The more numerous axially planned buildings, like Santa Sabina, had a long nave focusing on an apse. The nave, used for processional space, was usually flanked by side aisles. The first floor had columns lining the nave; the second floor contained a space decorated with mosaics; and the third floor had the clerestory, the window space. Early Christian basilicas have thin walls supporting wooden roofs with coffered ceilings (Figure 7.3b).

Centrally planned buildings were inspired by Roman buildings such as the Pantheon. The altar was placed in the middle of the building beneath a dome ringed with windows. Men stood around the altar, women in the side aisle, called an ambulatory.

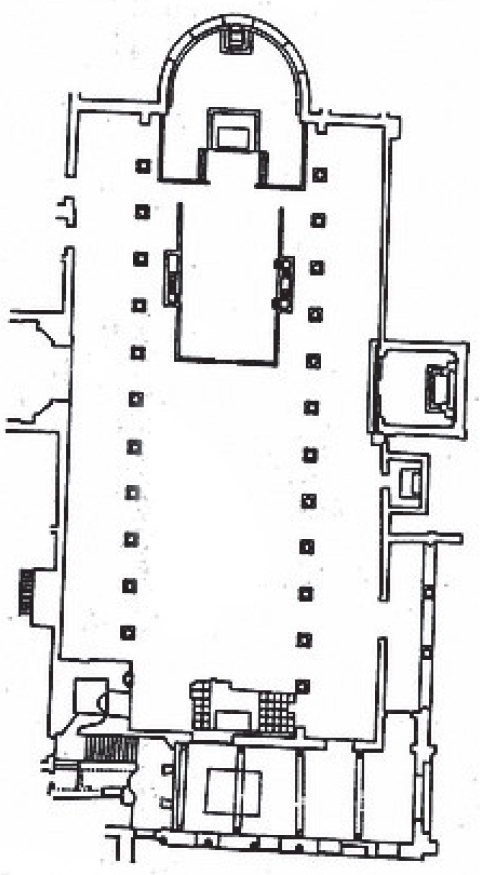

Santa Sabina, Late Antique Europe, 422–432, brick, stone, and wooden roof, Rome, Italy (Figures 7.3a, 7.3b, 7.3c)

Form

■Three-aisled basilica culminating in an apse; no transept.

■Long, tall, broad nave; axial plan.

■Windows not made of glass, but selenite, a type of transparent and colorless gypsum.

■Flat wooden roof; coffered ceiling; thin walls support a light roof.

Figure 7.3a: Rear and flank exterior of Santa Sabina, Late Antique Europe, 422–432, brick, stone, and wooden roof, Rome, Italy

Figure 7.3b: Nave of Santa Sabina

Figure 7.3c: Ground plan of Santa Sabina

Function

■Early Christian parish church.

■As in the Jewish tradition, men and women stood separately; the men stood in the main aisle, the women in the side aisles with a partial view.

Context

■Spolia: tall slender columns taken from the Temple of Juno in Rome, erected on this site; a statement about the triumph of Christianity over paganism.

■Bare exterior, sensitively decorated interior—represents the Christian whose exterior may be gross, but whose interior soul is beautiful.

■Built by Peter of Illyria.

Patronage

■According to an inscription in the narthex, the basilica was founded by Pope Celestine I (422–432).

Content Area Early Europe and Colonial Americas, Image 49

Web Source http://metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Age_of_Spirituality_Late_Antique_and_Early_Christian_Art_Third_to_Seventh_Century, pp. 266, 656–657

■Cross-Cultural Comparisons for Essay Question 1: Ground Plans of Religious Structures

–Angkor Wat (Figure 23.8e)

–Great Stupa (Figure 23.4d)

–Great Mosque at Córdoba (Figure 9.14e)

VOCABULARY

Ambulatory: a passageway around the apse or altar of a church

Apse: the endpoint of a church where the altar is located (Figure 7.2)

Atrium (plural: atria): a courtyard in a Roman house or before a Christian church (Figure 7.2)

Axial plan (Basilican plan, Longitudinal plan): a church with a long nave whose focus is the apse; so-called because it is designed along an axis (Figure 7.3)

Basilica: In Christian architecture, an axially planned church with a long nave, side aisles, and an apse for the altar (Figure 7.3)

Catacomb: an underground passageway used for burial (Figure 7.1a)

Central plan: a church having a circular plan with the altar in the middle

Clerestory: the third, or window, story of a church

Coffer: in architecture, a sunken panel in a ceiling

Cubicula: small underground rooms in catacombs serving as mortuary chapels

Gospels: the first four books of the New Testament that chronicle the life of Jesus

Loculi: openings in the walls of catacombs to receive the dead

Lunette: a crescent-shaped space, sometimes over a doorway, that contains sculpture or painting

Narthex: the closest part of the atrium to the basilica, it serves as vestibule, or lobby, of a church (Figure 7.2)

Nave: the main aisle of a church (Figure 7.2)

Orant figure: a figure with its hands raised in prayer (Figure 7.1b)

Spolia: in art history, the reuse of architectural or sculptural pieces in buildings generally different from their original contexts

Transept: an aisle in a church perpendicular to the nave, where the clergy originally stood (Figure 7.2)

SUMMARY

Christianity was an underground religion for the first three hundred years of its existence. The earliest surviving artwork produced by Christians was buried in the catacombs far from the average Roman’s view.

Imagery for Christian objects was derived from Roman precedents. Classical techniques such as fresco and mosaic flourished under Christian patronage, as did Roman figural compositions sometimes employing contrapposto. Moreover, Roman centrally and axially planned buildings found new life in Christian churches.

PRACTICE EXERCISES

Multiple-Choice

1.Construction of buildings like Santa Sabina relies on construction principles learned in the

(A)Basilica Ulpia

(B)Pantheon

(C)Colosseum

(D)Hagia Sophia

2.The painters of the catacombs preferred the fresco technique because

(A)oil paint does not blend well on wall surfaces

(B)mosaics were unavailable during this period

(C)fresco forms a permanent bond with the wall

(D)Christians have used fresco since Egyptian times

3.The Good Shepherd is an image in Early Christian catacombs that has its origins in the Bible, but pictorially the images are inspired by

(A)Greek images of shepherding

(B)Roman belief in agrarian virtues

(C)Muslim cultivation of extensively planned gardens

(D)prehistoric cave paintings of people and their animals

4.The division of painted spaces in the Good Shepherd fresco in the Catacombs of Priscilla is influenced by

(A)Roman wall paintings as seen in the House of the Vettii

(B)Greek vase painting as seen in the Niobides Krater

(C)Greek friezes as seen in the Great Altar of Zeus and Athena at Pergamon

(D)Etruscan wall paintings as seen in the Tomb of the Triclinium

5.After the catacombs in Rome were closed, legends grew around them that they were

(A)haunted spaces

(B)used to hide from Roman persecution

(C)exclusively for the Roman elite

(D)not really there, only the subject of legends

Short Essay

Practice Essay 4: Contextual Analysis

Suggested Time: 15 minutes

The images above show the interior and the ground plan of the church of Santa Sabina in Rome.

Describe the choice of materials used in the construction of this church.

Describe at least two elements of the Christian design that were adapted from non-Christian sources.

Using both the photograph and the ground plan, analyze how the design of the building is meant to accommodate the needs of Christian religious ceremonies.

ANSWER KEY

1.A

2.C

3.A

4.A

5.B

ANSWERS EXPLAINED

Multiple-Choice

1.(A) The Basilica Ulpia and other Roman basilicas formed a general inspiration for Christian churches.

2.(C) Christians did not exist in the Egyptian period. Oil painting was invented much later in the Renaissance. Mosaics were available, but were very expensive. Fresco forms a permanent bond with the wall surfaces, and was comparatively easy to use.

3.(A) The Good Shepherd image is inspired by a story from the Bible, but it has its pictorial roots in the shepherding image dating back to the Greeks.

4.(A) Roman paintings, such as the ones in the House of the Vettii, are separated by lines that define the wall spaces.

5.(B) Legends grew up about the catacombs that Christians, who were persecuted under the Romans, used them for hideaways. In truth, everyone in the ancient world knew where they were, so no one would have escaped by hiding there.

Short Essay Rubric

Task |

Point Value |

Key Points in a Good Response |

|

Describe the choice of materials used in the construction of this church. |

1 |

Answers could include: ■Wooden roof allowed for thinner walls in contrast to stone roofs that required heavier walls. ■Windows not made of glass but of selenite, a type of transparent and colorless gypsum. |

|

Describe at least two elements of the Christian design that were adapted from non-Christian sources. |

2 |

Answers could include: ■Spolia: tall slender columns taken from the Temple of Juno in Rome, erected on this site; a statement about the triumph of Christianity over paganism. ■Wooden roof similar to those in Roman basilicas. ■Building made of brick and stone as in Roman buildings. |

|

Using both the photograph and the ground plan, analyze how the design of the building is meant to accommodate the needs of Christian religious ceremonies. |

2; 1 point for photograph and 1 point for ground plan |

Answers could include: ■Christians worship congregationally facing a priest. Photograph and ground plan indicate placement of altar. ■Long nave for congregation; rounded apse sites the altar and highlights the priest. ■As in the Jewish tradition, men and women stood separately; the men stood in the main aisle, the women in the side aisles with a partial view. Ground plan indicates placement of aisles. |