Observe always that everything is the result of a change, and get used to thinking that there is nothing Nature loves so well as to change existing forms and to make new ones like them.

—Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

DARWIN CLOSED THE first edition of The Origin of Species with what has become perhaps the most widely quoted passage in all of biology:

There is a grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one: and that whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

It took him some twenty years to arrive at this phrasing. In earlier general sketches of his ideas, completed in 1842 and 1844, but never published, this passage was longer and notably different. The 1842 version read:

There is a simple grandeur in this view of life with its powers of growth, assimilation, and reproduction, being originally breathed into matter under one or a few forms, and that whilst this our planet has gone circling on according to fixed laws, and land and water, in a cycle of changes, have gone on replacing each other, that from so simple an origin, through the process of gradual selection of infinitesimal changes, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been evolved.

In 1844, Darwin tinkered with the choice of a few words, but the major changes came with the preparation of The Origin of Species for publication in 1859. Darwin removed the reference to the “process of gradual selection of infinitesimal changes” and condensed other phrases in ways that simplified the text and gave to it a poetic rhythm.

I have chosen four words that remained completely untouched throughout all versions and editions, “endless forms most beautiful,” as the inspiration for this book and the theme of this concluding chapter. This phrase captures the essence of the new science of Evo Devo. Here, I will discuss how the discoveries and perspectives of Evo Devo enlarge the grandeur of the evolutionary view of life, enrich our understanding of how Darwin’s endless forms have been and are being evolved, and have expanded and deepened the foundation of evolutionary thought.

My publisher informs me that I will not have twenty years to find just the right words, nor could I hope to capture the essence of this new discipline in such masterly prose as Darwin’s; nevertheless I will attempt to articulate four main points about the impact and importance of Evo Devo by way of summary and conclusion.

First, I assert that Evo Devo constitutes the third major act in a continuing evolutionary synthesis. Evo Devo has not just provided a critical missing piece of the Modern Synthesis—embryology—and integrated it with molecular genetics and traditional elements such as paleontology. The wholly unexpected nature of some of its key discoveries and the unprecedented quality and depth of evidence it has provided toward settling previously unresolved questions bestow it with a revolutionary character.

Second, Evo Devo provides a new means of teaching evolutionary principles in a more effective framework. By focusing on the drama of the evolution of form, and illustrating how changes in development and genes are the basis of evolution, the deep principles underlying the unity and diversity of life emerge. Furthermore, the visible forms of gene expression patterns in embryos and the concrete inventories of tool kit gene sets in different species provide more effective ways of illustrating evolutionary concepts than previous, more abstract approaches.

Third, because Evo Devo reveals and illustrates the evolutionary process and principles in such tangible ways, it has a critical role to play in the forefront of the societal struggle over the teaching of evolutionary biology.

And finally, the importance of evolutionary biology is far more than mere philosophy. The fate of the endless forms of Nature, including humans, depends on a broader understanding of human impacts on evolution.

Embryology is to me by far the strongest single class of facts in favor of change of forms, and not one, I think, of my reviewers has alluded to this.

—Charles Darwin, letter to Asa Gray,

September 10, 1860

The above quote reflects that embryology has always been an integral component of the evidence for evolution and the principle of common descent. The challenge for more than 100 years after Darwin was to explain how embryos—and thus the adult forms they produce—change. The Modern Synthesis added genetics to the evolutionary edifice, but geneticists of that era were largely restricted to studying small variations within species and did not know the chemical nature of the gene (i.e., DNA), let alone how genes affected form. The major accomplishment of the Modern Synthesis was the reconciliation between paleontological views of so-called macroevolution, or evolution above the species level, with genetic views of microevolution, the variation detectable within species. The synthesis asserted that large-scale changes in form as viewed in the fossil record could be explained by natural selection acting over long periods of time upon small genetic changes that produce variation within species. This was an extrapolation supported by a consensus opinion, but no one knew whether the genetic mechanisms governing large-scale change were the same or might be different than those affecting variation within species. Nothing was known about how genes affect form, which genes affect the evolution of form, or what kinds of changes in genes were responsible for evolution. Furthermore, once the structures of DNA and proteins were understood, the prevailing view of the architects and adherents of Modern Synthesis was that the process of random mutation and selection would so alter DNA and protein sequences that only closely related species would bear homologous genes.

Virtually everything I have described in chapters 3-10 has been discovered in the past twenty years. The insights provided by these discoveries have not just filled enormous gaps in our grasp of evolutionary processes, but they have also forced biologists to rethink completely their picture of how forms evolve. You have read detailed evidence of how differences in the way ancient tool kit genes are used has shaped the evolution of animal forms from Urbilateria to Homo sapiens. Here, I will summarize how major evolutionary ideas have been expanded, illuminated, or reconsidered based on this new body of evidence.

THE TOOLS FOR MAKING THE KINGDOM ARE ANCIENT

The first and still perhaps the most stunning discovery of Evo Devo is the ancient origin of the genes for building all sorts of animals (chapters 3 and 6). The fact that such different forms of animals are shaped by very similar sets of tool kit proteins was entirely unanticipated. The ramifications of these revolutionary findings are powerful and manifold.

First of all, this is entirely new and profound evidence for one of Darwin’s most important ideas—the descent of all forms from one (or a few) common ancestor. The shared genetic tool kit for development reveals deep connections between animal groups that were not at all appreciated from their dramatically different morphologies.

Second, the discovery that organs and structures that were long viewed as independent analogous inventions of different animals, such as eyes, hearts, and limbs, have common genetic ingredients controlling their formation has forced a complete change in our picture of how complex structures arise. Rather than being invented repeatedly from scratch, each eye, limb, or heart has evolved by modification of some ancient regulatory networks under the command of the same master gene or genes (chapter 3). Parts of these networks trace back to the last common ancestor of bilaterians (Urbilateria), and earlier forms (chapter 6).

Third, the deep history of the tool kit reveals that the invention of these genes was not the trigger of evolution. The bilaterian tool kit predated the Cambrian (chapter 6), the mammalian tool kit predated the rapid diversification of mammals in the Tertiary period, and the human tool kit long predated apes and other primates (chapter 10). It is clear that genes per se were not “drivers” of evolution. The genetic tool kit represents possibility—realization of its potential is ecologically driven.

LARGE-SCALE TRENDS IN ANIMAL DESIGN AND EVOLUTION HAVE A COMMON BASIS, AND ARE ENABLED BY THE PROPERTIES OF THE “DARK MATTER” OF THE GENOME

I have focused much attention in this book on the modular construction of animals from serially reiterated parts and the trend in evolution toward the greater specialization of these parts (chapter 1). Modularity is key to the building of complexity and the evolution of diversity. Complexity in animals is reflected by the number of different kinds of physical parts (cells, organs, appendages). Complexity has increased over time and in particular groups by the specialization of repeated parts and by the origin of new kinds of parts. Increases in complexity of both arthropods and vertebrates have occurred in some similar ways. We have seen that the deployment of different Hox genes in serially repeated structures differentiates the form and function of arthropod and vertebrate structures. The success of these groups has been enabled by the flexibility of the systems governing Hox gene deployment such that individual structures can evolve independently of others.

The crucial insights into how this independence, and hence complexity and diversity, is achieved come from understanding the properties of genetic switches (chapter 5). Because individual genes can be and are governed by numerous independent switches, mutations in one switch can be selected for that have no effect on other switches or the function of the protein encoded by a gene. Evolutionary changes in switches are responsible for shifting the zones of Hox genes underlying large-scale differences in body organization in various animals (chapter 6), for finer-scale differences in the appearance of the same structure in different animals (chapters 7 and 8), and for the origin and modification of new pattern elements (chapter 8). The key to the making of “endless” forms (i.e., diversity) is in the astronomical number of possible combinations of regulatory inputs and switches. Switches integrate inputs relating to three-dimensional space, cell and tissue identity, and relative developmental time. Any of these parameters can be modified by adding, subtracting, or fine-tuning inputs into switches. Furthermore, the number of switches can expand or contract in the course of evolution. Even with a finite set of tool kit proteins that act on switches, the combinatorial power is enormous.

The realization of this power is shaped, of course, by natural selection. Not all paths are explored, not all patterns are made. Nevertheless, we delight in the 17,000 or so extant patterns of butterfly wings; the great variety of sizes, shapes, and marking of fellow mammals; the geometry of the bodies and shells of marine animals; and even the 300,000 or more species of beetles. It has been estimated that the millions of animal species now living represent perhaps just 1 percent of the billion or more forms that have evolved in the past 500 million years. We know of many diverse groups that have long since disappeared: the dinosaurs, trilobites, many weird and wonderful Cambrian animals, and more than a dozen hominins. The combinatorial power of the genetic tool kit acting on vast arrays of genetic switches has produced this complexity and diversity.

EXISTING GENES AND STRUCTURES PROVIDE THE MEANS FOR INNOVATION

We have seen that insects, pterosaurs, birds, or bats did not invent “wing” genes (chapter 7), butterflies a “spot” gene (chapter 8), or humans a “bipedalism” or “speech” gene (chapter 10). Rather, innovation in all of these groups has been a matter of modifying existing structures and of teaching old genes new tricks.

The key to innovation at the genetic level is the multifunctionality of tool kit genes. The multifunctionality of tool kit genes stems from their deployment at different times and places through batteries of genetic switches. In this manner, a protein such as Distal-less can act at one time to promote limb formation, and at another to promote eye-spot development. The protein made each time is identical, so the difference in function is due to its action on different switches in these different contexts.

At an anatomical level, multifunctionality and redundancy are keys to understanding the evolutionary transitions in structures. We saw this especially in arthropods, where the shifting of a function such as feeding to one of a battery of appendages freed other appendages to become specialized for walking, swimming, or other activities. In a similar fashion, the gill branches in aquatic arthropod ancestors became modified into book gills, book lungs, tubular tracheae, spinnerets, and wings.

Evo Devo has revealed the continuity among forms that was masked or about which there were uncertainties based on appearance alone. By revealing the developmental similarities among structures, Evo Devo presents a wholly new kind of evidence that is far more objective than morphology alone. These insights into the evolution of novelty strengthen aspects of Darwin’s original ideas that some have found most difficult to grasp.

The history of these structures also illustrates how “endless forms” evolve through cycles of invention and expansion. New structures open up new ways of living. The insect wing led to the evolution of dragon-flies and mayflies, butterflies and beetles, fleas and flies, and more. The expansion of these groups was catalyzed in turn by a cycle of innovation and expansion by making modifications to the wings or body plan—scale coloration systems in moths and butterflies, a hard covering in beetles, a sophisticated balancing hindwing in flies.

Why are existing body parts and genes the more frequent pathway to innovation? This is a matter of probability. Variation in existing structures and genes is more likely to arise than are new structures or genes, and this variation is therefore more abundant for selection to act upon. As François Jacob explained so eloquently, Nature works as a tinkerer with available materials, not as an engineer does by design. The invention of wings never occurred from scratch, but by modifying a gill branch (insects) or forelimbs (three times). Trends in evolution reflect the paths that are most available and therefore those taken most frequently.

Evo Devo has revealed that evolution can and does repeat itself at the levels of structures and patterns, as well as of individual genes. If evolution takes the most probable path, via existing structures and genes, then when confronted with similar selection pressures, different species may follow the same path to adaptation. We saw this in the evolution of feeding appendages in crustacea (chapter 6), pelvic spine reduction in sticklebacks (chapter 7), and other cases of limb reduction in vertebrates. We also saw that melanic fur or plumage patterns can arise through mutations in the very same gene in different species, and even the very same position in this gene (chapter 9).

These instances of evolution repeating itself directly address difficulties some have had in grasping the role of random mutation in the evolutionary process. Some people have found it hard to imagine how novelty and complexity arise from “a random process.” The key distinction is that while the generation of genetic variation by mutation is a completely random process, the sorting of these variations as to which will persist and which will be discarded is determined by a powerful, selective nonrandom process. Of the hundreds of millions or billions of individual base pairs in an animal genome, all are equally susceptible to random copying errors or physical damage that cause mutations. But only a tiny fraction of all possible mutations can alter a mammal’s coat in a viable manner, or reduce a stickleback’s spines without causing catastrophic collateral damage. In large populations of animals, over eons of time, such mutations will arise simply as a matter of probability. When they do occur, positive selection upon the trait they affect will cause them to spread in populations over time.

Jacques Monod captured this interplay of randomness and selection in evolution must eloquently in the title of his landmark book, Chance and Necessity (a reference to the Greek philosopher Democritus who said, “Everything existing in the Universe is the fruit of chance and necessity”). Evolution is indeed a matter of chance, but in the random lottery of mutations, some numbers and combinations better meet the imperatives of ecological necessity, and they arise and are selected for repeatedly.

We also saw in rock pocket mice that the same species can use different paths to a similar solution. And, while pterosaurs, birds, and bats evolved wings out of their forelimbs, they did so in fundamentally different ways. Similar ecological demands and opportunities have selected for similar adaptations, but the developmental solutions will sometimes differ in detail.

By revealing the genetic and developmental mechanisms underlying change, Evo Devo allows us to compare and contrast the evolutionary paths of different groups. Long-standing mysteries such as Batesian mimicry in butterflies, melanism in moths, and even the evolution of finch beak size and shape now lie within our grasp. We shall soon have detailed pictures of many of the classic examples of natural selection and understand in depth how variation arises and is selected for.

WHAT IS TRUE OF SPECIES IS TRUE OF THE KINGDOM

The architects of the Modern Synthesis united evolutionary disciplines by asserting that the mechanisms that operated at the level of individuals in populations and species were sufficient to account for the great differences that evolve over geologic time. If, as some have proposed at various times over the past century, changes in form were due to very rare, special mutations that, for example, change a homeotic gene in just a particular way, then this extrapolation would not be justified. For a half century since the Modern Synthesis, this specter of a “hopeful monster” has lingered. The facts of Evo Devo squash it.

Evolution of homeotic genes and the traits they control has been very important, but has not occurred by different means than the sorts of mutations and variation that typically arise in populations. The preservation of Hox genes and other tool kit genes for more than 500 million years illustrates that the pressure to maintain these proteins has generally been as great as that upon any class of molecules. Instead, the evolutionary tinkering of switches, from those of master Hox genes to those of humble pigmentation enzymes, typically underlies the evolution of form. The continuity of the tool kit and the continuity of structures throughout this vast time illustrate that we need not invoke very rare or special mechanisms to explain large-scale change. The extrapolation from small-scale variation to large-scale evolution is well justified. In evolutionary parlance, Evo Devo reveals that macroevolution is the product of microevolution writ large.

Don’t know much about history

Don’t know much biology

Don’t know much about science books

—Sam Cooke, Herb Alpert, and Lou Adler,

“Wonderful World” (1960)

The teaching of evolution faces two challenges. The first is that it is a vast and growing subject that encompasses many disciplines. The second is that it is actively opposed, particularly in the United States, by some (but not all!) religious factions. I will address the new contribution Evo Devo can make to improving general public understanding first, the issue of opposition later.

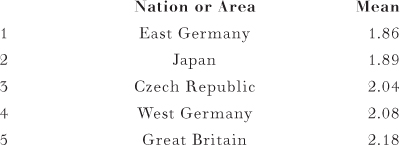

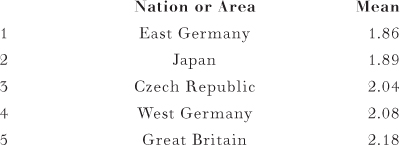

In general, the public understanding of evolution in the United States is particularly abominable. In a survey of citizens in twenty-one countries or regions regarding general environmental and scientific knowledge, the United States placed dead last on the question of human evolution. When asked to respond to the question “In your opinion, how true is this? Human beings developed from earlier species of animals,” using a four-point scale (1 represented definitely true, 2 probably true, 3 probably not true, and 4 definitely not true), the citizens of various countries responded correctly as follows:

Looking at the bright side, the United States can only move up from here.

In another survey, by the National Science Board in 1996, 52 percent of Americans polled either agreed that (32 percent) or did not know (20 percent) whether the statement “The earliest humans lived at the same time as the dinosaurs” was true.

Score that fact as two points for The Flintstones, zero for Darwin, Huxley, and the educational system of the world’s most wealthy, powerful, and technologically driven nation.

The scandal of this ignorance is on par, I would say, with not knowing how the United States was formed, the content of its Constitution, or the roots of Western civilization. This knowledge is considered basic literacy and taught and repeated at many grade levels. So, too, is biology and earth science for which evolution must provide the basic framework. Yet the statistics are appalling.

The situation is bad enough, and reflected in other figures about science and math literacy, that the blame can probably be shared in many quarters. There are plenty of books written about and organizations studying the general problem of scientific illiteracy and its causes; I won’t get into finger-pointing here. The only way up is through education. I would rather focus on what biologists and their allies at all levels of the teaching profession can do to improve matters, particularly in regard to evolution.

First, we must insist that evolution is much more than just a topic in biology—it is the foundation of the entire discipline. Biology without evolution is like physics without gravity. Just as we cannot explain the structure of the universe, the orbits of the planets and moon, or tides from mere measurement, we cannot explain human biology or Earth’s biodiversity via a compendium of thousands of little facts. All general survey courses and texts must have evolution as their central unifying theme.

With respect to the scientific content to be taught, Evo Devo has much to contribute that is new, tangible, and convincing. Since the Modern Synthesis, most expositions of the evolutionary process have focused on microevolutionary mechanisms. Millions of biology students have been taught the view (from population genetics) that “evolution is change in gene frequencies.” Isn’t that an inspiring theme? This view forces the explanation toward mathematics and abstract descriptions of genes, and away from butterflies and zebras, or Australopithecines and Neanderthals.

The evolution of form is the main drama of life’s story, both as found in the fossil record and in the diversity of living species. So, let’s teach that story. Instead of “change in gene frequencies,” let’s try “evolution of form is change in development.” This is, of course, a throwback to the Darwin-Huxley era, when embryology played a central role in the development of all evolutionary thought. There are several advantages of an embryological approach to teaching evolution.

First, it is a small leap to go from the building of complexity in one generation from egg to adult, to appreciating how increments of change in the process, assimilated over greater time periods, produce increasingly diverse forms.

Second, we now have a very firm grasp of how development is controlled. We can explain how tool kit proteins shape form, that tool kit genes are shared by all animals, and that differences in form arise from changing the way they are used. The principle of descent by modification (of development) is crystal clear.

Third, an enormous practical advantage is the visual nature of the Evo Devo perspective. The Chinese proverb I cited in chapter 4, “Hearing about something a hundred times is not as good as seeing it once,” is sound educational doctrine. We learn more by combining visuals with text. Let’s show students embryos, Hox clusters, stripes, spots, and all the glory of the making of animal form. The evolutionary concepts follow naturally.

A fourth benefit of this approach is that it brings genetics much closer to the powerful evidence of paleontology. Dinosaurs and trilobites are the poster children of evolution, and they inspire the vast majority of those who touch them. By placing these wonders of the ancient past in a continuum from the Cambrian to the present, life’s history is made much more tangible. It would indeed be a wonderful world if every student had guided, repeated classroom contact with some fossils.

Let me offer a couple more general suggestions. Natural selection is often at best described as a “just so story” of adaptations: finches beaks changed due to the type of food available, moths got darker because of pollution, etc. But I do not think that the power of small increments of selection, compounded over hundreds or thousands of generations, is widely taught or understood. The commonly repeated phrase “survival of the fittest” connotes more of a gladiator contest than the subtle power of selection to act on very small differences in overall survival and fecundity. The spread of favorable mutations in populations is easily simulated and illustrated, and it underscores the time dimension of evolution.

Finally, at the university level, the evolutionary view of life should be as fundamental to a college degree as Psychology 101 or Western Civilization. But rather than asking students to memorize and regurgitate mountains of testable facts, we should emphasize study of the history of the discovery of evolution, its major characters and ideas, and the basic lines of evidence. This would do far more to inform citizens and prepare teachers than forcing students to remember the Latin names of taxa. We are stoning our children to utter boredom with little pebbles and missing the big picture. The drama of the story of evolution will recapture student interest.

There is, especially in the United States, another obstacle besides content and teaching methods to evolutionary literacy; I will address that next. But even without the active opposition, we can do better, and we have to do better.

If you are convinced of a matter, you must take sides or you don’t deserve to succeed.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe,

Propylaea (1798)

In the short time between the first and second edition of The Origin of Species, Darwin inserted three more words into that famous closing paragraph, adding “by the Creator” to rewrite the phrase as “having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one …” Darwin later expressed his regret for doing so in a letter to botanist J. D. Hooker: “But I have long regretted that I truckled to public opinion, and used the Pentateuchal term of creation, by which I really meant ‘appeared’ by some wholly unknown process.”

The insertion of these words was intended to appease critics and make Darwin’s evolutionary ideas more palatable. It has certainly served to fuel much speculation about Darwin’s actual religious views. For some, this olive branch and Darwin’s reticence in disclosing his beliefs (which are revealed to some degree only in private correspondence and unpublished notebooks) were the foundation for reconciling and accommodating evolution and religion.

Plenty of scientists and a broad spectrum of religious denominations have found such an accommodation. For example, in 1996, Pope John Paul II reiterated the Catholic position that the human body has evolved according to natural processes. Furthermore, he noted that the evidence for evolution had increased greatly, to the point where it is “more than a hypothesis.” (While giving a stronger endorsement than his predecessors, the Pope is echoing a long-standing position of the Roman Catholic Church. My ordained teachers at St. Francis de Sales High School in Toledo introduced me to Darwin and evolution.) Coming from the head of the largest Christian faith in the world, with an infamously slow history of incorporating advances in science, the Pope’s statements might eventually mark a turning point in evolution’s long struggle for acceptance. But while some denominations have explicitly accepted the reality of biological evolution, fundamentalists who insist upon a literal reading of the Bible (referred to here as “creationists”) remain firmly opposed to evolutionary science and actively promote legislation aimed at crippling the teaching of evolution in public schools.

Goethe also said, “Nothing is worse than active ignorance,” and it is the agenda of these lost souls that the scientific and educational communities must thwart. I want to be very clear here in my position. I believe that the teaching of evolution and science is best served by promoting the scientific method and scientific knowledge and not by attacking religious views. The latter is a futile, counterproductive battle. However, I also believe, as many denominations have also concluded, that religion is better served by promoting and evolving its respective teachings and theologies, and not by attacking science, which is definitely a losing strategy.

Charles Harper, executive director of the John Templeton Foundation, an organization interested in the relationship between theology and science, wrote recently in the leading science journal Nature: “As scientific knowledge grows, religious commitments predicated on ‘gaps’ in scientific understanding will invariably shrink as those gaps are closed. Those Christians who are currently fighting evolutionary science will eventually need to take it seriously.” Harper is right. In this time of unprecedented power in understanding embryos, genes, and genomes, and with the continual expansion of the fossil record, those gaps are fast disappearing.

One example of a mistaken faith in those gaps is that of biochemist Michael Behe, who in 1996 published Darwin’s Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution. Written by a credentialed scientist, Behe’s book was received as a godsend by creationists. But Behe’s main claim, that the living cell is an entity of irreducible complexity, is empty. Behe was counting on biology to hit a wall in reducing complex phenomena to molecular processes. He joins a long line of prognosticators whose pessimistic forecasts have been obliterated in the continuing revolution in the life sciences.

Scott Gilbert, a biologist at Swarthmore College, author of the leading college text of developmental biology, and an accomplished historian of embryology and evolutionary biology, has summarized the Behe position, and its failure: “To creationists, the synthesis of evolution and genetics cannot explain how some fish became amphibians, how some reptiles became mammals, or how some apes became human. … Behe named this inability to explain the creation of new taxa through genetics ‘Darwin’s black box.’ When the box is opened, he expects evidence of the Deity to be found. However, inside Darwin’s black box resides merely another type of genetics—developmental genetics.”

Developmental genetics has been shedding new light on the making of complexity and the evolution of diversity for twenty years. Creationists just plain refuse to see it. How is such overt evidence ignored or dismissed? I can’t pretend to understand the psychological mechanisms that allow humans to deny reality. But I do understand the desperate political and rhetorical tactics of those who, holding a losing hand, refuse to accept it. In the creationists’ case, it is to assert that:

1. Evolution is just a theory, and there are other theories (creation or Intelligent Design) to which, out of fairness, equal treatment should be given.

or,

2. Evolution is a fraud perpetuated by scientists, or just bad science. For example, commenting on the Pope’s statement, Bible-Science Association Director Ian Taylor asserted, “With the Pope’s statement the Roman Catholic Church takes another step toward embracing one of the greatest deceptions ever foisted on mankind.… Honest scientists who know their business, such as … Dr. Michael Behe … have very forcefully pointed out, for example, that the irreducible complexity of the living cell makes chance-driven evolution absolutely impossible.”

or,

3. Because scientists often disagree or are uncertain as to all mechanisms of evolution, or the relative contribution of different forces, or don’t know all of the details of life’s history, this uncertainty is evidence of doubt and therefore evolution is a weak theory that should not be taught.

Evolution a deception perpetuated by dishonest scientists? In their zeal, the creationists appear to have forgotten what I thought would have been one of their guiding principles, that thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

As exasperating as the continuous battle with creationists may seem, the scientific community is now better organized and more prepared to deal with the movement. But, the battle against ignorance is not won. Rather, as Henry David Thoreau reminds us, this is a long haul:

You can hardly convince a man of an error in a life-time, but must content yourself with the reflection that the progress of science is slow. If he is not convinced, his grandchildren may be. The geologists tell us that it took one hundred years to prove that fossils are organic and one hundred and fifty more to prove they are not to be referred to the Noachian deluge.

The struggle to advance evolutionary thought is not limited to science and scientists. Theologians such as John Haught of Georgetown University have written extensively about the need to incorporate the evolutionary perspective of science into a modern fabric of theology. Haught, who views the scientific evidence in favor of evolution as overwhelming, points out that since the text of the Bible “was composed in a prescientific age, its primary meaning cannot be unfolded in the idiom of twentieth century science” (as creationism demands). He explains:

Many theologians have still not faced the fact that we live in a world after and not before Darwin and that an evolving cosmos looks a lot different from the world-pictures in which most religious thought was born and nurtured. If it is to survive in the intellectual climate of today, therefore, our theology requires fresh expression in evolutionary terms. When we think about God in the post-Darwinian period we cannot have exactly the same thoughts that Augustine, Aquinas, or for the matter our grandparents and parents had. Today we need to recast all of theology in evolutionary terms.

Haught has wrestled with the significance of evolution for such theological issues as suffering, freedom, and creation. Darwin wrestled with these matters as well. Haught presents the view that creation without evolution would produce a pallid and impoverished world that would lack “all the drama, diversity, adventure, and intense beauty that evolution has produced. It might have a listless harmony to it, but it would have none of the novelty, contrast, danger, upheavals, and grandeur that evolution has in fact brought over billions of years.”

This is certainly not traditional theology. But Haught’s message is logical—theology must evolve, or face becoming irrelevant. We’ll know it is a full-fledged revolution when fossils, genes, and embryos are discussed (positively) in Sunday school.

The stakes in the broader adoption of an evolutionary perspective are more than philosophical. Understanding the history of our planet, both recently and in the deep past, is key to its intelligent stewardship, and to its preservation for human societies.

The evolution of Homo sapiens and of our culture and technology has had and is having enormous impacts on biodiversity. It is estimated that before agriculture was introduced, we numbered perhaps 10 million. Our population reached 300 million by A.D. 1 and accelerated greatly with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, reaching 1 billion around 1800. We are now at 6 billion and projected to climb to 9 billion in the next fifty years, a thousand-fold increase in just 10,000 years.

Even before the most recent boom, humans and their cultures have had dramatic effects wherever they settled. For myself, one of the most poignant examples of our impact is depicted in my most favorite place on Earth, Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory of Australia. In addition to its spectacular diversity of living flora and fauna, Kakadu is the site of the longest continuous history of human habitation. The rock art of the Australian Aborigines is among the oldest anywhere in the world. At Ubirr, in the northern area of the park, there are many galleries with some figures drawn perhaps as long as twenty to forty thousand years ago and others made in very recent times. High up on the western face of an overhang of the main gallery is a painting of a thylacine (figure 11.1), a carnivorous marsupial also know as Van Diemen’s land tiger and the Tasmanian wolf. The animal is long gone from the Northern Territory and the Australian mainland and is now completely extinct—the last thylacine from Tasmania died in a zoo in 1936. On the mainland, the thylacine was most likely the victim of dingos that came to Australia with the Aboriginal migrations. The rock art at Kakadu reminds us of what once thrived in that remarkable place, both in terms of wildlife and members of our own species.

FIG. 11.1 The extinct thylacine. Top, Aboriginal rock art from western Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, depicting a thylacine, a striped carnivorous marsupial long extinct from the mainland. Bottom, naturalist sketch of Tasmanian tiger (thylacine), which was still living in Tasmania in the early twentieth century. PHOTO COURTESY OF DR. CHRISTOPHER CHIPPENDALE, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY

Similar stories follow human settlement elsewhere in the world. Cave art in France portrays extinct bison and rhinoceros, piles of bones are the only remnants of the large flightless moas of New Zealand exterminated by the Maoris (figure 11.2), sketches are the only record of dodos exterminated by sailors on the island of Mauritius (figure 11.2), and the last giant ground sloths and woolly mammoths were killed off by Paleo-Indians. The quagga (figure 11.3), one of four zebra species or subspecies alive at the time of Darwin’s birth, was extinct in the wild by the time of his death.

But the loss of these individual species pales in comparison to current trends of animal extinction. The large-scale destruction of habitat, the degradation of water and soil quality, the pollution of the air, and the loss of rain forests and coral reefs are wreaking global havoc on biodiversity. The butterflies and parrots of the Amazon are no longer as numerous or diverse as Bates found them, and if Darwin returned to the Galapagos Islands he would find that the very symbol of the islands, the Galapagos tortoise, as well as the large ground finch and sharp-beaked ground finch, have gone extinct on some islands. Under relentless human assault, Nature’s forms are not endless, nor are the most beautiful being spared.

FIG. 11.2 The dodo and the moa. These birds were exterminated by humans on the islands of Mauritius and New Zealand, respectively.

I am not so naïve to believe that science can solve all of the world’s problems, but ignorance of science, or denial of its facts, is courting doom. Recall Huxley’s words when he addressed the Royal Institution at the dawn of the first revolution in biology. He asked the audience what role England would have in the grand and noble reformation of thought then under way:

Will England play this part? That depends on how you, the public, deal with science. Cherish her, venerate her, follow her methods faithfully and implicitly in their application to all branches of human thought; and the future of this people will be greater than the past. Listen to those who would silence and crush her, and I fear our children will see the glory of England vanishing like Arthur in the mist.

FIG. 11.3 The quagga. This zebra species or subspecies went extinct in the late 1800s.

The question now at hand is not the glory of England, or of America, but of Nature. What a tragic irony, that the more we understand of biology, the less we have of it to learn from and to enjoy. What will be the legacy of this new century—to cherish and protect Nature, or to see butterflies and zebras and much more vanish into legend like the thylacine, moa, and dodo?