The merging of units and sub-units to form what the writers of the military manuals would describe as the ‘perfect phalanx’ highlights an element of the pike-formation’s performance on the field of battle that has seen its fair share of scholarly contention: how rigid was a whole line of pikemen once the army had deployed in line? Some scholars suggest that the Hellenistic pike-phalanx lacked the ability to adapt to varying terrain and changes in the tactical situation. Adcock, for example, states that the pike-phalanx was ‘muscle-bound and without flexibility’.¹ Pietrykowski similarly calls the pike-phalanx ‘ponderous’ and states that the formation was ‘fatally flawed at its core’ due to its rigidity ‘which, in turn, inhibited tactical flexibility’.² Somewhat contradictorily, Anson says that the phalanx was organized into ‘interdependent blocks of infantry’ requiring ‘less emphasis on the ability of the individual soldier and encouraging unit solidarity’ while also stating thatthe formation ‘lacked flexibility’.³

Other scholars suggest the exact opposite, claiming that there was an inherent level of adaptability within the structure of the Hellenistic pike-phalanx. Burn plainly states that ‘Alexander’s formations were, naturally, flexible’.⁴ Featherstone states that it was Alexander who broke the pike-phalanx into smaller units, turning it into a ‘spear-hedged’, highly mobile formation ‘rather than a juggernaut of moving spear points’.⁵ Warry calls the pike-phalanx ‘a highly flexible unit, capable of assuming various formations’.⁶

Other scholars offer that the early phalanx did possess tactical flexibility but that this ability was later lost during the time of the Successors. Bosworth suggests that flexibility was what mattered most to the phalanx.⁷ Gabriel states that it is often mistakenly believed that the pike-phalanx lacked flexibility and that it was, in fact, less prone to breaking up than the Classical Age hoplite phalanx until the armies of the later Successor Period expanded the size and depth of the formation to a point where it could hardly manoeuvre at all.⁸ Tarn states that, by the second century BC, the flexibility of Alexander’s phalanx had been lost and rough or hilly ground always disrupted these later, rigid, formations.⁹ Pietrykowski states that ‘relentless training, brilliant leadership and a forgivingly flexible construction rendered the phalanx of Philip [II] and Alexander [the Great] far better suited to an irregular battlefield than the Hellenistic armies of later decades; suggesting that it was the longer pikes of the Successor period which made later phalanxes ‘less flexible and less manoeuvrable’.¹⁰

A review of the ancient descriptions of the pike-phalanx in action tends to agree with those scholars who advocate a certain level of flexibility within the phalanx. As far back as the early reign of Philip II, and well into the Successor Period, the sources detail pike formations which are both adaptable in deployment and flexible in operation. At Chaeronea in 338BC, for example, the Macedonian army deployed and ‘individual units were positioned where the situation required’.¹¹ At Thebes in 335BC, Alexander divided his army into three separate groups, some of which must have contained units of pike infantry, one to attack the palisade which had been erected in front of the city, another (which included a contingent of Macedonians) to face an advance by the Thebans, and another which was posted in reserve behind the lines and who advanced to support the units facing the Thebans when they became hard pressed.¹² This shows that not only could sections of the pike phalanx be deployed separately from each other, but that reserve units could be brought up and into the fight when required.¹³ This can only be considered a use of pikemen in a line that was not rigid. Units of pikemen, rather than the whole phalanx, were also regularly used in many of Alexander’s sieges and assaults as independent contingents.¹⁴

While the use of individual contingents, rather than the whole battleline, would seem an obvious use of manpower in siege warfare, the literary sources also detail the use of individual units of the phalanx in open field engagements as well. At Gaugamela in 331BC, for example, Alexander advanced his right wing, which contained some pike units, in an oblique line towards the Persian left.¹⁵ Curtius states that the entire line, rather than just the right wing, advanced at an angle.¹⁶ It is almost impossible for a pike-phalanx, either in part or as a whole, to advance at an angle if the formation is a solid, rigid line. However, it is much easier to advance individual units obliquely. This suggests that Alexander’s phalanx was not an inflexible battle line. Rather it seems that the pike-phalanx was comprised of a number of independent ‘combat groups’ – made up of the various units and sub-units of the phalanx – who acted in concert with each other within the parameters of any predetermined plan or spontaneous command while attempting to limit any fragmentation of the line as a whole which may occur as different units advanced and/or engaged. Later, when a gap had opened in the Persian line opposite the Macedonian right, Alexander directed his attack into this opening using his cavalry and ‘the section of the phalanx stationed there’.¹⁷ This shows that the pike units on the right of the line could operate independently from the rest. This independence is confirmed by Arrian who describes how the merarchia commanded by Simmias, on the left of the line between the merarchiae of Craterus and Polyperchon at Gaugamela, ‘halted their unit [Arrian uses the term ‘phalanx’ in its generic sense] and were fighting where they stood as the Macedonian left was reported to be in trouble’.¹⁸ Thus it seems clear that each of the merarchiae of Alexander’s line were operating somewhat independently on the field. Again, this indicates that the phalanx was not one rigid battleline.

This flexibility of the phalanx was also used to arrange the deployment of an army to meet certain conditions on the battlefield and to cater to an overall plan of battle. At Asculum in 279BC, Pyrrhus posted units of native levies in between the units of his phalanx.¹⁹ At Sellasia in 222BC, Antigonus similarly posted units of allied infantry between the units of his pike-phalanx to provide the line with enough flexibility to assault up a hill while simultaneously maintaining unit cohesion.²⁰ At Magnesia in 190BC, Antiochus had his pike-phalanx divided into ten divisions with thirty-two elephants positioned between each contingent.²¹ Thus, right from the onset, all of these deployments of the phalanx would not have been a rigid line of pikemen as some scholars suggest.

Even while marching, the phalanx operated as interdependent units. Any redeployment from column into line conducted in the manner of Alexander’s advance towards Issus (see pages 311-317) can only have been undertaken on a unit by unit basis. Similarly, the wheeling of Machanidas’ phalanx at Mantinea in 207BC could only have been conducted in units rather than as a whole line.²² At the same engagement, Polybius describes how Philopoemen, commanding the opposing Achaean forces, deployed his phalanx in contingents with spaces left between.²³ As the battle began, the first section of the Achaean troops wheeled to the left onto clear ground and then advanced into battle without breaking ranks.²⁴ All of these descriptions can only be taken as references to a pike-phalanx that is both flexible in its arrangement and adaptable to varying tactical situations due to it operating as semi-independent combat groups. Similarly, during the parade at Daphne in 168BC, Antiochus IV is said to have ordered ‘those to advance, those to halt, and assigned others to their positions, as occasion required’.²⁵ This again suggests a pike-phalanx which operated as independent units rather than as a solid, rigid, line.

Aelian also details a large number of other ways that the phalanx could be configured other than just in a horizontal or oblique line. These include such formations as the concave or convex crescent (meneoides [μηνοειδής]), with a variant also known as the kyrtē [Kυpτὴ] formation), the open-ended square (epicampios emprosthia [ἐπικάμπιος ἐμπροσθια]), the wedge (embolon [ἔμβoλoν]), and the hollow square (plaision [πλαίσιoν]).²⁶ In Illyria in 335BC, Alexander the Great formed part of his troops into a wedge, and formations such as defensive squares were adopted by Eumenes’ troops at Gabiene in 316BC and by Antiochus III’s phalanx at Magnesia in 190BC.²⁷ These formations are difficult, if not impossible, to form with a single, rigid, line, but can be accomplished by simply arranging the units and sub-units of the phalanx into the desired configuration. At Issus, the pike units on the right wing, finding the Persians who were opposing them in flight, wheeled inwards to attack troops who were holding the centre of the phalanx at bay at the river’s edge.²⁸ Again, this shows that the units of the phalanx could operate independently of each other and, if the need arose, come to each other’s aid. Dickinson suggests that the phalanx could change formation easily.²⁹ This can only be based upon an acknowledgement that the phalanx was composed of several individual units which could be rearranged with ease. Such references also illustrate a continued use of varied arrangements of the pike-phalanx across almost the whole of the Hellenistic Period.

Regardless of whether Aelian’s descriptions of alternative formations are taken as indicative of the variable deployments of the early phalanx under Philip and Alexander (which Aelian suggests he is writing about), or of the later formations of the Successor Period, or both, it is clear that the phalanx was highly adaptable and not inflexible. Importantly, if these descriptions are seen as references to the formations of the later Successor Period – and the references to the adoption of defensive squares at Gabiene and Magnesia suggest that, if not wholly a Successor Period concept, then the use of such formations may simply be a continuance of earlier phalanx configurations – it is clear that the use of longer pikes in this time period did not inhibit the adaptability of the phalanx as some scholars suggest. This flexibility in the deployment, manoeuvring and operation of the phalanx also impacted on how it moved into the attack regardless of its initial configuration.

It is often stated by modern scholars that the Hellenistic pike-phalanx could only operate on certain terrain. Anson, for example, states that the phalanx required ‘level and clear ground with no obstacles’.³⁰ Snodgrass similarly says that the phalanx could be clumsy on rough terrain.³¹ Markle states that ‘the sarissa armed phalanx could only be effectively used on a level plain unbroken by streams, ditches or rivers’ and that uneven or broken ground was likely to cause gaps to form in the line.³² English suggests that Alexander’s troops flattening a grain field with their pikes in Illyria in 335BC (Arr. Anab. 1.4.1) was to create a level battlefield which suited the phalanx best.³³ Griffith, in a fairly generalized statement, claims that ‘acting in big formations on fairly level and unbroken ground, the [phalanx] was very formidable’.³⁴

Such claims, either referenced or otherwise, are based upon a passage by Polybius. In his examination of the pike-phalanx, Polybius states:

The phalanx…requires ground that is level and bare which has no obstacles such as ditches, clefts, ravines running together, ridges, [or] flowing rivers; for all of the aforementioned are sufficient to impede and fragment such a formation.³⁵

The sentiment of this passage can also be found in Livy (who used Polybius as a source) who declares that ‘the slightest unevenness in the terrain renders the phalanx ineffective’.³⁶ Plutarch’s account of the battle of Pydna, the event being described by both Polybius and Livy, also includes a declaration that the phalanx ‘required firm footing and smooth ground’.³⁷

However, there are several issues with the use of Polybius’ passage to account for the operation of the pike-phalanx. Firstly, as Morgan points out, the word used by Polybius to describe the most preferable ground for the phalanx to operate on (epipedos), while regularly translated as ‘flat’ (as in the above quote) can also mean ‘sloped’. Indeed, Polybius himself uses the word epipedos on a number of occasions to refer to ground with anything from a gentle undulation to a fairly steep incline such as a description of the peninsula of Sinope (4.56.6), the lofty ridges at Sellasia (5.24.3), and the valley of Leontini (7.6.3).³⁸ Consequently, it is possible to interpret Polybius’ description as meaning that the phalanx required terrain that was ‘sloped/undulating and bare…’. Furthermore, even if the passage is taken as meaning ‘flat’, just because this was the most preferable ground for the phalanx to operate on does not necessarily mean that it was the only ground that it could operate on. Hammond suggests that while ‘ideally’ the phalanx fought on flat ground, it could also fight on difficult ground.³⁹ In fact, some of the major pike-phalanx engagements of the Hellenistic Age were fought on ground which Polybius would have considered unsuitable.

As far back as the dawn of the Hellenistic Age, the phalanx was fighting on terrain that was anything but flat. In 350BC, Phocion held the high ground against Philip II and waited for the Macedonian attack.⁴⁰ This shows that the early Hellenistic pike-phalanx was capable of attacking up an incline. High ground was also employed at the battle of Chaeronea in 338BC, but this time by Philip himself. Polyaenus tells us how the units of the Macedonian phalanx on the right of the line withdrew to high ground to their rear, enticing the Athenian left flank to advance. Once in possession of this high ground, Philip’s troops re-engaged causing the Athenian line to break.⁴¹ Thus it seems clear that at least part of Philip’s pike-phalanx could effectively engage an opponent on sloping ground and, with the advantage of fighting downhill, fight quite effectively.⁴² Hammond goes as far as to suggest that the counterattack from the high ground was the key to securing Macedonian victory at Chaeronea.⁴³ If this was the case, then uneven ground could actually work in the phalanx’s favour.

High ground was also a dominant feature of the battle of Sellasia in 222BC. Antigonus Doson had invaded southern Greece to aid the Achaean League against Cleomenes III of Sparta. Cleomenes secured the heights of two hills, called Olympus and Euas, where the road to Sparta and the river Oenous ran between the hills.⁴⁴ Both positions were occupied with contingents of the Spartan pike-phalanx and were additionally reinforced with a ditch and palisade.⁴⁵ On the right of their line, the attacking Macedonians formed up their phalanx with units of allied infantry in between each contingent.⁴⁶ The slopes of Euas, which range from a 15° incline near the base of the hill to around 20° nearer to the summit, were much steeper than that of neighbouring Olympus.⁴⁷ It has been suggested that Antigonus’ alternating deployment of the phalanx units on his right wing may have been to provide the line with greater flexibility to cope with this steep ground.⁴⁸ On the Macedonian left, on the other hand, where the incline of Olympus was less, Polybius specifically states that the phalanx was deployed without any gaps or intervals, but does state that it was arranged in a double depth due to the narrowness of the front.⁴⁹

The Macedonian right assaulted up Euas and, according to Polybius, their line was unbroken when it reached the Spartan position on the summit.⁵⁰ If correct, this shows that, with the insertion of more mobile troops to act as hinges between the units of the pike-phalanx, this formation could effectively advance up fairly steep terrain and possibly even fight over a defensive ditch and palisade. In another indication of how steep terrain could favour the pike-phalanx, Polybius outlines how he believed that one of the major mistakes made by the Spartans at Sellasia was to not have their phalanx on Euas attack down the slope and engage the advancing Macedonians using the advantages of the high ground which, if need be, would have provided them with a means of retreat.⁵¹ Such claims by Polybius seem odd when it is considered that in his own account of the battle of Pydna, he supposedly claims that the pike-phalanx can only operate on ‘flat’ ground. This in itself, suggests that Polybius’ passage should be better translated as ‘sloped’ or ‘inclined’ ground at best.

On the Macedonian left at Sellasia, the pike-phalanx also assaulted up the slopes of Olympus, but here Cleomenes ordered his phalanx to tear down part of their protective palisade and attack downhill (as Polybius says they should have also done on Euas).⁵² Polybius states that both sides lowered their pikes and engaged each other on the slopes of the hill – showing that the pike-phalanx could engage on such ground while moving in either direction.⁵³ However, the impetus of the downhill Spartan attack forced the Macedonian line back onto the plain below.⁵⁴ Plutarch states that the Macedonian right, after defeating those holding Euas, moved back down the hill and attacked Cleomenes and his Spartans – most likely from the rear – and secured the victory.⁵⁵

In this engagement, pike-phalanxes from both sides functioned effectively on anything but level ground. Both wings of the Macedonian phalanx attacked up fairly steep hills with the right wing apparently attacking over the ditch surrounding the Spartan position on the summit of Euas. Furthermore, the Macedonian left wing seems to have been able to withdraw down the slopes of Olympus without breaking the line or devolving into a rout, the Spartan right wing was able to very effectively attack downhill, in an action which must have also involved them crossing the ditch they had dug in front of their position, and (at least according to Plutarch) the Macedonian right was able to turn about and advance back down Euas to engage the Spartans from behind. Importantly, if Plutarch’s statement is accurate, the Macedonian right-wing phalanx would have also needed to have crossed the terrain below the hills in order to engage. Plutarch describes the valley as ‘full of ravines, water courses and generally irregular’.⁵⁶ None of these features seem to have impeded the functioning of the phalanx which indicates that it could operate on steep and/or broken ground.

The battle of Cynoscephalae in 197BC was also fought up and over high ground which Plutarch describes as ‘the sharp tops of hills lying close beside each other’.⁵⁷ Polybius calls the ridge ‘rough, precipitous and of considerable height’.⁵⁸ Pietrykowski calls the ridge upon which the battle was fought ‘a true liability’ to the ‘ponderous phalanx’.⁵⁹ Morgan, on the other hand, points out that the terrain does not seem to have been a deciding factor in the outcome of the battle.⁶⁰ Both of these claims seem to be only partially correct as, depending upon the exact nature of the ground on certain parts of the ridge, the phalanx was either hindered (which ultimately led to its defeat) or not.

The Macedonian army of Philip V, and the Roman army of Titus Flaminius, were both encamped on either side of the ridge at Cynoscephalae. Philip is said to have considered the ground unsuitable and unfavourable for a major engagement but, following initial contact and skirmishing between advance units from both sides, and the receipt of favourable reports from the ridge above which stated that the Romans were in retreat, Philip began to commit more troops to the action including elements of his pike-phalanx.⁶¹ Units of Philip’s right-wing phalanx surmounted the ridge at a run: a manoeuvre which must have necessitated their pikes being held vertically.⁶² Livy says that, once in position and arranged in double depth, the phalangites were ordered to drop their pikes and fight with swords because the length of the weapons was a hindrance.⁶³ Both Polybius and Plutarch, on the other hand, state that the phalanx engaged with its pikes lowered.⁶⁴ Indeed, there are several reasons why Livy’s account should be considered incorrect in this matter. Firstly, Livy later states that the phalanx was unable to turn about to face an attack from the rear.⁶⁵ While this is true of a phalanx with its pikes lowered, it can be easily accomplished by one just fighting with swords. This suggests that the Macedonians were using the sarissa. Secondly, Livy also states that, at the end of the battle, parts of the phalanx signalled their surrender by raising their pikes.⁶⁶ It is unlikely that the members of the phalanx had put away their swords, picked up their pikes – which would have been somewhere uphill behind them as the sources all state that the Macedonian right wing pushed the Romans down the slope – and then used them to signal their surrender. It is more likely that the phalanx had been using their pikes all along.

The phalanx units on the Macedonian right wing effectively engaged the Romans using the advantages of the high ground to their fullest. Plutarch states that the Romans facing these units could not withstand their attack.⁶⁷ It was a different story on the Macedonian left, however, and it was in this quarter that the nature of the terrain may have hampered (and eventually defeated) the pike-phalanx. Livy says that additional pike units were brought up in column – a formation he says is better suited to a march than a battle – rather than in extended line. The ground here may have been more broken than on the right and this caused large gaps to open in the phalanx as it deployed: gaps which the more mobile Roman maniples were able to exploit to defeat the Macedonian left and then swing around to attack the remaining units on the Macedonian right.⁶⁸ Polybius states that this fracture of the phalanx on the left was due to some units already being engaged, others only just making the top of the ridge, while others were in position but were not advancing down the hill. Interestingly, none of these factors have much to do with the nature of the terrain itself and, as such, the extent to which the ground caused the fragmentation of the Macedonian line at Cynoscephalae cannot be conclusively determined. However, it seems clear that it is not the incline of the battlefield which is a hindrance to the operation of the pike-phalanx, but whether or not the line can be maintained on the terrain that the battle is fought upon. This again goes against Polybius’ claim that the phalanx could only operate on ‘flat’ ground.

Another feature which Polybius states could disrupt the function of the phalanx is the presence of a ditch, ravine or river on the battlefield. Yet Alexander the Great’s two battles at Granicus in 334BC and Issus in 333BC were both fought with the pike-phalanx advancing over watercourses and both resulted in Macedonian victories. Arrian’s account of the battle at Granicus contains few details of the infantry action but he does describe the banks of the river as ‘very high, in some places like cliffs’ and how the Persians waited on the far bank so that they could fall upon the Macedonians as they emerged from their crossing.⁶⁹ Arrian and Plutarch also note how the current of the river was strong enough to pull Alexander and his cavalry downstream when they started to cross.⁷⁰ In another comment on the banks of the river, Diodorus similarly states that the Persians held the far side as they thought that they could easily defeat the Macedonians when their phalanx was disrupted as they crossed.⁷¹ Plutarch also notes the uneven slopes of the river banks, but also states that the phalanx crossed the river and quickly put the Persians to flight.⁷² Polyaenus simply states that the phalanx fell upon the enemy and defeated them.⁷³ There are few recorded casualties for the infantry in this engagement.⁷⁴ This would suggest that, regardless of how the banks are described or how fast the river was flowing, the river posed little obstacle to the advance of the phalanx.

At Issus, Arrian again describes the banks as, ‘in many places, precipitous’.⁷⁵ Unlike at Granicus, however, at Issus the banks of the river do seem to have caused some problems for the phalanx. Arrian states that gaps began to form in the line as sections of the phalanx negotiated the crossing and while some units were held up by a stronger resistance than in other areas.⁷⁶ This finds many similarities with the fragmentation of the phalanx at Cynoscephalae. Other units of the phalanx at Issus were able to cross easily – aided by the fact that the Persians opposing them had fled – reform and hit the remaining Persians in the flank.⁷⁷ Markle suggests that both Ptolemy and Callisthenes, the main sources for Arrian, exaggerated the difficulty of the crossing at Issus to make the victory more impressive.⁷⁸ Yet the fact cannot be dismissed that Alexander suffered more casualties among his pike-phalanx at Issus than he did at Granicus. The one thing that could have been a deciding factor in this outcome was the nature of the river that the phalanx had to cross and how it caused part of his line to lose cohesion. Furthermore, Markle claims that the nature of a watercourse at Issus would have made using the sarissa untenable and, as such, suggests that this indicates that Alexander’s troops were not using the sarissa at all.⁷⁹ For the members of the pike-phalanx, it would be far easier to use the longer reach afforded by the sarissa to engage opponents on an elevated riverbank, as they crossed a river, than it would have been if they were only using more traditional length spears. Curtius’ description of Alexander’s infantry at Issus aiming their weapons at the faces of those arrayed on the bank above them seems to confirm the use of a lengthy weapon from the riverbed – most likely the sarissa. This further suggests that Alexander’s troops were using lengthy pikes at both Granicus and Issus.

In his critique of Callisthenes’ account of the battle of Issus, Polybius ponders:

how did a unit of phalangites mount the river’s bank which was both steep and covered with thorny bushes? For this would seem contrary to reason. One must not attribute such an absurdity to Alexander who acquired experience and training in warfare from childhood. Rather, one should attribute it to the historian who, on account of his own inexperience, is unable to distinguish the possible from the impossible in such matters. So much for…Callisthenes.⁸⁰

Polybius also declares ‘what can be less prepared than a phalanx advancing in line but broken and disunited’.⁸¹

While such accusations seem initially valid, Polybius is missing some important considerations in his claims. Firstly, Alexander had successfully attacked with the pike-phalanx across a river at Granicus the previous year so there would be no reason to assume that he thought he could not do it again at Issus. Secondly, the river does seem to have posed problems to the phalanx as it crossed (at least in Arrian’s account) which could be attributable to the slopes and bushes cited by Polybius. Lastly, despite Polybius claiming that such factual errors belonged to those with no experience, unlike Polybius, Callisthenes was actually present at the engagement and may have been an eye witness to the crossing. Consequently, there is little reason to place doubt on the description of the operations of the pike-phalanx at Issus that have come down to us second-hand though Arrian. Strangely, even though his account of the battle is much briefer than that of Arrian, Plutarch states that Fortune had presented Alexander with the ideal terrain for the battle.⁸² Despite the much harder struggle at Issus, it is clear that Alexander’s phalanx could advance and engage across a watercourse with only limited disruption to the line.

Ditches and rivers were also features of other battles during the later Hellenistic Age. At Mantinea in 207BC, for example, the Spartan pike-phalanx of Machanidas attempted to fight its way across a defensive ditch and was defeated.⁸³ However, the important thing to note is that the force holding the other side of the ditch was another pike-phalanx and not some other form of infantry. The ancient texts time and again outline the benefit of using pikearmed phalangites with the benefit of high ground and, while Polybius does state that the Spartan line at Mantinea fragmented as it crossed the ditch, part of the reason for their defeat would have undoubtedly been trying to overcome the lengthy weapons of the opposing formation arrayed against them from elevated ground. Other phalanxes, for example those of Alexander at Granicus and Issus, seem to have had only minor difficulties in crossing a river against opponents who were not armed with long pikes. A similar outcome occurred when Eumenes faced off against Antigonus at the river Pasitigris in 317BC. In this engagement, Antigonus attempted a river crossing but Eumenes and his troops ‘withstood him, joined battle with him, killed many of his men and filled the stream with dead bodies’.⁸⁴ Yet again, it is the fact that the higher ground (or in this case bank) was held by opposing forces which seems to have been a more decisive factor in the outcome rather thanjust the influence of the terrain.

When Pyrrhus attacked the city of Sparta in 272BC, the city’s defences were reinforced with a ditch 6 cubits (2.88m) wide and 4 cubits (1.92m) deep.⁸⁵ Plutarch says that the freshly turned earth of this defensive work made it hard for the attackers to gain a firm footing.⁸⁶ It is interesting to note that a lengthy sarissa, held in its ready position, projects ahead of the bearer by up to nearly 12 cubits (5.76m) if it is of the 14 cubit variety common to the late Hellenistic Period and is held by the last 2 cubits of its length. Plutarch recounts how Hieronymus considered the Spartan entrenchment as being rather small.⁸⁷ The validity of this statement can be seen in the fact that a phalangite standing on one side of the ditch would easily be able to reach an opponent standing on the other due to the length of his pike. Thus the only danger to the advancing pike-phalanx would have been when they actually chose to cross the ditch. Had the phalangites simply remained on their side, the Spartans would have undoubtedly been forced to pull back as they would not have been able to engage their opponents. The key element of the perils of this defensive work as it is described by Plutarch is that it was the freshly turned earth, rather than the nature of the ditch itself, that was an impediment to the advance of the phalanx.

Channels and watercourses also played a part in the battle of Pydna in 168BC: although not in the way, or to the extent, that Polybius would suggest in his critique of the phalanx. Plutarch observes that the plain of Pydna was cut by the rivers Aeson and Leucus but that, at the time of the battle (the end of summer) the water was not deep.⁸⁸ This comment about the apparent lack of depth of the rivers suggests that both rivers were substantially deeper at other times of the year and, as such, the banks of the streams at the time of the encounter could have been rather steep. Plutarch states that the Macedonian commander, Perseus, thought that these would disrupt the Roman formations.⁸⁹ This suggests that the initial Macedonian strategy was to hold a defensive position and attack the Romans when they advanced. Hammond, in his analysis of the battle concludes that the two opposing battlelines ran from the southwest to the northeast and, as such, the two rivers on the battlefield, which ran roughly west to east, dissected both formations.⁹⁰ As Plutarch notes, Paulus waited for the sun to pass its zenith so that it would not be shining into the faces of his troops when he attacked.⁹¹ This would only make sense if both armies were deployed north-south (with the Romans facing east). While Hammond’s orientation of the lines in this manner conforms with the statement made by Plutarch, it must also be considered that in doing so parts of both armies had to have advanced down, or at least across, sections of a riverbed in order to engage. However these obstacles do not seem to have impeded either army to any great extent.

As if to confirm this tactic of a Macedonian defensive action, Plutarch describes Paulus as being reluctant to go into action against a phalanx that was ‘already drawn up and fully formed’.⁹² What happened to this initial strategy is not stated but, not long afterwards, the Macedonians are said to have quickly gone on the offensive and advanced almost up to the Roman camp.⁹³ This advance would have included parts of the pike-phalanx crossing both rivers which do not seem to have posed much of an impediment to the formation as it moved forward. However, as the battle continued, dangerous gaps began to form in the Macedonian line which allowed the Romans to attack individual phalangites from the flank and rear. Plutarch partially attributes this fragmentation of the phalanx to the terrain, which he says was uneven, but also to the very length of the phalanx and to the fact that some units were hard pressed while others were continuing to advance.⁹⁴ This finds similarities with both Alexander’s battle at Issus and Philip V’s engagement at Cynoscephalae. Yet it must also be noted that, prior to this occurrence, and while the phalanx maintained its cohesion, Plutarch states that the phalanx was ‘everywhere unassailable’, that Paulus was frightened by the sight of the organized phalanx, and that, due to the losses his troops were suffering, he rent his clothes in despair.⁹⁵ Further evidence that some of the fighting took place in and across the water channels is found in Plutarch’s statement that the following day the waters of the Leucas were stained with blood.⁹⁶ Consequently, it is yet again clear that it is in the maintenance of the line (or not) where the deciding factor in the outcome of the battle involving a pike-phalanx lies rather than the terrain upon which it was fought.⁹⁷ Livy attributes the Roman victory to this factor alone in his account of the battle.⁹⁸

Indeed, the maintenance of the line, or not, was the major contributing factor to the success or failure of the pike-phalanx in action. The use of units and sub-units, while providing the pike-phalanx with a certain level of tactical flexibility, also created the potential for the greatest danger to the formation: the opening up of gaps in the line. There are numerous ancient texts which contain generalised comments to the effect that, if the cohesion of the line is retained, a pike formation is almost unbeatable.⁹⁹ Such claims would also have to assume that the vulnerable flanks of the phalanx were protected as well.

How these gaps formed was due to a number of combined factors. Polybius states that whether the pike-phalanx advances and puts an opponent to flight, or is itself turned, the line will fragment as, in one scenario, units of the phalanx will pursue the routed enemy while, in the other, fleeing phalangites will not maintain their formation.¹⁰⁰ Plutarch states that the uneven terrain at Pydna resulted in the phalanx being unable to maintain ‘as close a formation as possible’ (using the term synaspismos in its generic sense) and that this also caused gaps to form in the line.¹⁰¹ Plutarch also states that gaps will form in the phalanx when parts of it are hard pressed while other sections continue to advance.¹⁰² This is exactly what happened at both Issus and Cynoscephalae which shows that this was a vulnerability that existed within the pike-phalanx across the entire Hellenistic Period.

The only way to avoid such perils would be for the entire line to halt its advance if part of it became hard-pressed. Arrian states that the integrity and safety of the whole line depended upon each man holding his position.¹⁰³ This would not only relate to each phalangite keeping his position within his file, but to each file and sub-unit keeping their respective positions across the line as a whole. However, due to the semi-independent nature of the sub-units of the phalanx, and the sheer size of some of the battlelines of the Hellenistic Age, there was not enough command and control to keep the entire line intact and, as a result, gaps would inevitably form.¹⁰⁴ In some instances unit commanders were able to gauge what was happening around them and halt their formation to prevent further fragmentation of the line. We see this in the actions of the units within the merarchia of Simmias at the battle of Gaugamela who ‘halted their unit and were fighting where they stood as the Macedonian left was reported to be in trouble’.¹⁰⁵

When gaps formed in the line, this was when the phalangite was most vulnerable. By exploiting these gaps, more mobile opponents could move inside the sets of serried pikes, negating the advantage that such a lengthy weapon provided, and attack at close-quarters with short reach weapons, or attack the phalangites from the side. In either case the panoply of the phalangite placed him at a considerable disadvantage. The lengthy sarissa, for example, was practically useless as an individual combative weapon due to its size and weight and the formation, not matter how fragmented, made it difficult for the phalangite to individually turn and face a direct threat from the side or rear. Markle offers that the only place that a sarissa did function effectively was within the confines of the massed phalanx.¹⁰⁶ Plutarch also comments on the small size of the phalangite sword and shield and that these made them no match for the Romans in hand-to-hand combat once a gap had been exploited.¹⁰⁷

The creation of such gaps posed little threat when facing another pike-phalanx, the members of which could not exploit it and, even if an inevitability, the success of the pike-phalanx against more mobile opponents suggests that any deficiencies in the formation were countered by many of its other advantages in most cases. So long as enough of the line remained intact to pin the enemy in place for the amount of time required for a flanking cavalry attack to work, then the phalanx was reasonably secure – as per Alexander’s battle at Issus. If, on the other hand, the protection for the flanks of the phalanx was removed, or any flanking attack against the enemy line failed to achieve its purpose, then the gaps that had formed in the line as a result of the phalanx’s advance could result in its undoing. Yet the separation of the line did not mean immediate defeat. On the contrary, the ancient literature shows that the pike-phalanx could even operate reasonably well on terrain which could do nothing but cause the line to fragment.

In Polybius’ critique of the phalanx he states that the formation could be interrupted by obstacles. However, even generally rough and/or wooded terrain did not always negatively impact the function of the pike-phalanx. At Asculum in 279BC, the Romans engaged Pyrrhus of Epirus on terrain which Plutarch describes as ‘rough ground where his [i.e. Pyrrhus’] cavalry could not operate, and along the wooded banks of a river…’¹⁰⁸ Pyrrhus engaged on this ground with his whole army, including his pike-phalanx, and secured a long and hard fought victory.¹⁰⁹ Polybius states that Pyrrhus deployed with alternating units of phalangites and allied troops across his line.¹¹⁰ This arrangement may have been to ensure that his line was more flexible, and therefore less likely to have gaps form, as it advanced across the difficult terrain. Polybius makes the comment in his examination of the pike-phalanx that it is almost impossible to find clear and obstacle free land for the pike-phalanx to fight on.¹¹¹ While generalised in nature, such comments fail to consider that if obstacle free ground was so rare, yet crucial to the proper functioning of the pike-phalanx, why anyone would have adopted such a style of fighting in the first place or have been able to use it to such great effect for almost two centuries up to the time that Polybius was writing. Clearly, obstacles of any shape or form, whether they be rivers, ditches, ridges or trees did not have a significant impact of the operation of the pike-phalanx so long as adequate precautions were taken to ensure the flexibility and maintenance of the line.

Even a narrow fronted battlefield seems to have been little impediment to the pike-phalanx. In 191BC, Antiochus III occupied the narrow pass of Thermopylae in central Greece against the army of the Roman consul Marcus Acilius Glabrio.¹¹² Part of this army included a contingent of sarissaphori who were positioned as a second line of infantry, against a series of defensive works that had been constructed.¹¹³ In the narrow pass, Antiochus’ phalangites engaged the Romans ‘with their sarissae presented in a massed order, the formation with which the Macedonians from the time of Alexander [the Great] and Philip [II] used to strike terror into enemies who did not dare to engage the thick array of pikes presented to them’.¹¹⁴ The phalangites seem to have held their own in the initial stages of the battle – Livy says they ‘easily withstood the Romans’.¹¹⁵ When they became hard pressed, the phalangites withdrew inside the fortifications and ‘made what amounted to another palisade with their pikes thrust out in front of them’ and the Macedonians used this position to easily fend off the attacking Romans.¹¹⁶ This resistance continued until a force of Romans managed to get around behind the Macedonians, using the same path that the Persians had used to outflank Leonidas and his Spartans back in 480BC, which caused the formation to rout and flee for their camp¹¹⁷

Frontinus states that the phalanx did not like fighting in cramped quarters.¹¹⁸ Hammond offers that phalangites were not well suited to fighting in narrow areas like streets or in siege warfare.¹¹⁹ However, this is precisely the kind of terrain where a unit of pikemen would have been at their best. In narrow fronted areas like streets or passes like Thermopylae, where the flanks of the formation were protected by buildings or natural features, a contingent of pikemen could easily hold their own against any opponent with shorter reach weapons so long as the high ground was not occupied by the enemy who could then use this position to rain missiles down upon the phalangites.¹²⁰ If the files could be maintained, the pikes strongly presented, and the formation not crowded by opposing troops, pikemen could simply either advance forward and drive or kill everything before them or hold their position and let the attacking enemy impale themselves on their pikes. However, if the formation was not maintained on such narrow terrain, then any warrior was in trouble regardless of the type of weapon he was using. Plutarch describes in detail the confusion of urban warfare in the Hellenistic Age in his account of Pyrrhus’ assault on Argos in 272BC. In this attack, Pyrrhus’ troops were driven out of the town square, where Plutarch says there was plenty of room to fight and give ground, only to have his formations spoiled by reinforcements coming the other way. In the confusion, orders could not be heard, several elephants went wild and trampled all underfoot, and ‘once a man had drawn his sword or aimed his spear it was impossible for him to sheathe [it] or put it up again, but it would pierce whoever stood in its way’.¹²¹ It is this type of cramped and confused environment where the use of weapons was limited, rather than any reference to the nature of the terrain itself, that Frontinus must be referring to. Had Pyrrhus’ troops been able to withdraw without such confusion, much of the carnage mentioned by Plutarch could possibly have been avoided.

Despite such accounts, phalangites did take part in many assaults on urban areas – particularly ones that were taken through breaches in the walls rather than through the use of assault ladders. At both Tyre and Gaza, for example, some of the troops who stormed the cities were from units of Alexander’s pike-phalanx.¹²² This suggests that either these troops were employing their pikes in an urban environment, or may have been using other, smaller weapons, such as the front halves of their sarissae or just their swords. In any case, these units would have been fighting in a narrow, enclosed space, but with their flanks somewhat protected. Indeed, if contingents of Classical hoplites such as the 300 Spartans, arranged in close order, were able to hold the Thermopylae pass for two and a half days in 480BC, and inflict substantial casualties among their enemies, then even a single syntagma of phalangites could have held the same position with their longer pikes almost indefinitely. This shows that the narrowness of the terrain was also not an impediment to the functioning of the pike-phalanx and, depending upon the circumstances, could actually make the position even stronger.

Markle suggests that sarissa-armed infantry were never led across rivers or ditches except by incompetent commanders.¹²³ However, a review of the literary accounts of some of the major confrontations of the Hellenistic Period shows that in many cases experienced commanders from Philip II to Perseus successfully engaged opponents with pike-phalanxes on this very type of terrain. In other cases, pike formations fought effectively on hilly or narrow ground – contrary to what Polybius would have us believe in his examination of the phalanx. Anderson suggests that Polybius’ description of the unsuitability of the phalanx on rough terrain may simply be an exaggeration to illustrate his point concerning the loss at Pydna.¹²⁴ Based upon the different terrains that the phalanx successfully fought upon, if Polybius’ passage is not translated in another way, this seems more than likely. Thus it seems clear that the use of units and sub-units within the structure of the pike-phalanx made it a very flexible formation and one that could be configured and used on almost any battlefield of the ancient world.

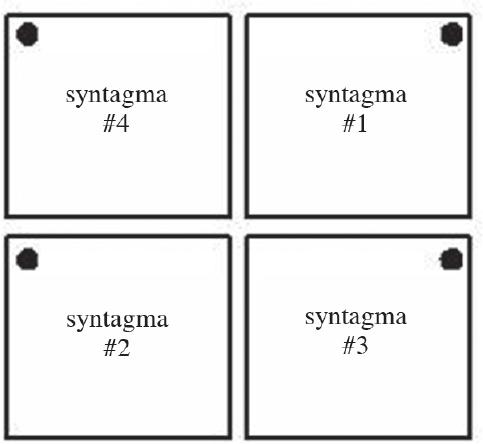

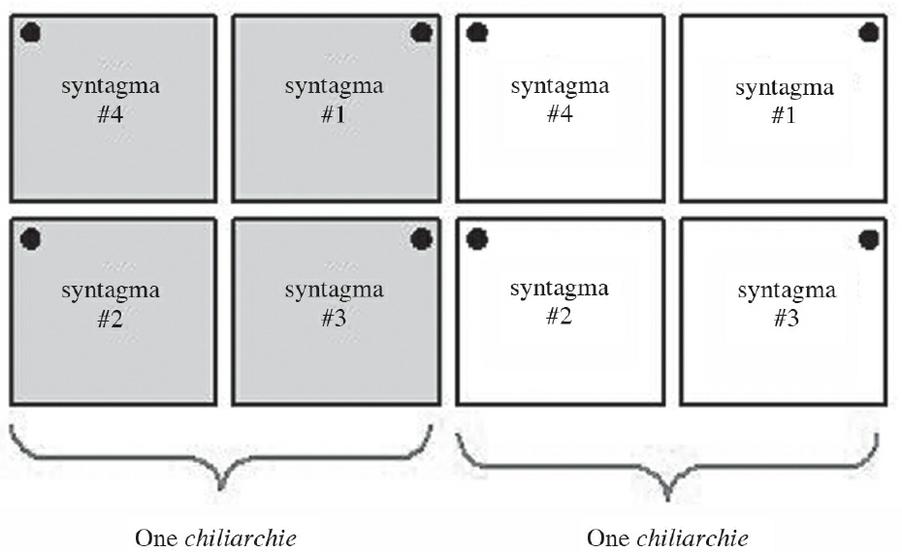

A deployed pike-phalanx could be a lengthy formation. A single syntagma of 256 men arranged in sixteen files (for example, with each file occupying an intermediate-order interval of 96cm per man) would possess a frontage of around 16m. Each chiliarchia of the phalanx, if all four of its constituent syntagmae were arranged side-by-side with no interval between, would possess a frontage of 64m. Each merarchia, with its four constituent chiliarchiae similarly arranged side-by-side with no interval between, would possess a frontage of 256m. Thus a pike-phalanx such as that of Alexander the Great, comprised of six separate merarchiae, when at full strength and deployed in a continuous line in its standard depth, would stretch for more than 1.5km. The effective control of such a lengthy formation in battle came down to a number of factors across all levels of command. The effective control of the phalanx was not just due to the positioning of officers across its front rank and the symmetrical distribution of their command abilities to support each other, but through careful planning, clearly understood commands with an easy means of delivering them, and the adaptability of the pike-phalanx in general.

In many instances how the phalanx was to form up and fight was decided well before the commencement of hostilities at a pre-battle council of senior officers. Alexander the Great held just such a council meeting at Granicus in 334BC where, upon receiving reports from his scouts on the Persian positions, he immediately gave all necessary orders in preparation for a battle.¹²⁵ This was not a one sided discussion and Alexander’s senior general, Parmenion, was able to offer his own advice – advice Alexander readily dismissed.¹²⁶ If Arrian is correct in stating that the deployment of the merarchiae at Granicus followed a rotating roster of command to some extent, it would seem likely that these dispositions were confirmed in such a pre-battle council as well.¹²⁷ Alexander’s advance from column into line at Issus the following year must have also been determined well beforehand as is suggested by Curtius (see pages 311-317).¹²⁸ At Tyre in 333BC, officers of varying ranks were present at strategic conferences.¹²⁹ Machanidas’ deployment from column into line at Mantinea in 207BC must have similarly followed a preconceived plan and operational deployment (see pages 322-326).¹³⁰

A major pre-battle council was also held by Alexander prior to the battle of Gaugamela in 331BC which involved commanding officers of all of the different contingents within the army – all of whom seem to have been able to contribute to the discussion. Arrian states that:

…he stopped his phalanx [i.e. army]…and again summoned the Companions, generals, squadron commanders and the leaders of the allied and foreign mercenaries, and posed the question whether he should advance his phalanx at once from this point, as most of them urged, or, as Parmenion thought best, encamp there for the time being, reconnoitre the whole of the terrain…and make a thorough survey of the enemy’s positions. Parmenion’s advice prevailed and they camped there, in the order in which they were to go into battle¹³¹

This passage provides a great deal of information about what took place at these pre-battle councils. Firstly, it is carried out at a time which allows for the options for the timing of the operation to be debated: in this case either to encamp and fight on another day or engage immediately. Secondly, Arrian’s passage shows that the order of battle was pre-arranged at these meetings. Finally, these councils involved representatives of all the units within the army. This would allow the commander of each contingent to know its exact place in the battleline for the ensuing battle and what it was expected to do on the day. As Hammond notes, the discussions and conclusions reached at the pre-battle councils had to envisage how the ensuing battle would unfold as all of the senior commanders present at them would be in the thick of the fighting in their own individual sectors of the battlefield once hostilities had commenced.¹³² Importantly, even if it was decided to go into battle immediately, it can only be assumed that enough time would have been left for these orders and dispositions to be relayed down through the chain of command to each respective sub-unit of the formation. If it was decided to encamp, then presumably orders for the night watch would have been issued, rosters for eating, resting and other duties would have been finalized, and these too would have to be filtered down to each and every member of the army.¹³³

Following this council at Gaugamela, Arrian states that, following an inspection of the army, Alexander summoned the officers again and issued further instructions for how the army was to conduct itself on the day of the battle.¹³⁴ Parmenion is said to have gone to Alexander again following this second council to offer other options such as an immediate night attack on the Persian position – advice which, again, Alexander rejected.¹³⁵ This shows that, once plans had been set, they could be refined further, and possibly even altered, with discussions at the highest command level.

At the Hydaspes, orders were given to certain units regarding what to do if the battle progressed in a certain way. Craterus, for example, commanding units holding the riverbank to keep the Indians of king Porus in check, was instructed by Alexander:

not to attempt a crossing until Porus and his army had left his camp to attack Alexander’s forces [who were attacking from a different direction], or until he had leamt that Porus was in flight and [Alexander] victorious; ‘but should take a part of his army and lead it against me’, Alexander continued, ‘and leave another part behind in his camp with elephants, still stay where you are. If, however, Porus takes all of his elephants with him against me, but leaves some part of his army behind in his camp, cross with all speed…¹³⁶

It is unlikely that most battle plans were as elaborate, or as reliant upon certain conditions, as those given to Craterus at the Hydaspes. It is more likely that, as with Alexander’s council at Gaugamela, the main concern with the plan would have been where each unit was to deploy in the line. From here, the majority of operational tactics for the pike-phalanx seem to have simply been for an order to be given for the phalanx to ‘lower pikes’ (καταßαλoυσαι τας σαpίσας) and advance into action (see following).¹³⁷ This simplicity of direction would ensure that instructions were not confused or misinterpreted as they were passed down the line. It also partially explains why Alexander used the exact same tactic – a frontal advance with the phalanx while the right wing cavalry attacked from the flank – at each of his four major battles with only slight variations on a theme.

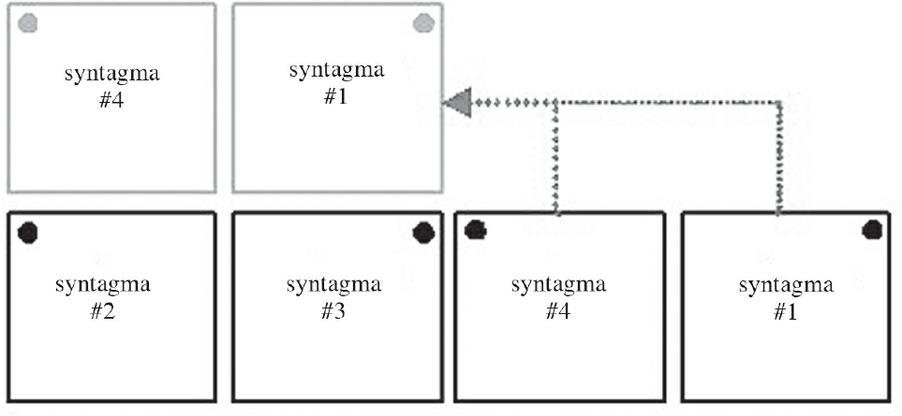

Once battle had been joined, a complex system for relaying commands was used to capitalise on the flexibility of the phalanx and to exploit any tactical opportunity that presented itself. Other commands put into effect orders that had been pre-planned. Arrian states that at Gaugamela the units of Alexander’s phalanx had been ordered to open gaps to counter an attack by Persian scythe-bearing chariots. Arrian uses the past tense ‘they had been ordered’ (ὥσπερ παρήγγελτo αὐτοῖς) here which suggests that this had been part of the plan developed from Alexander’s reconnaissance of the enemy position and the considered method of their attack. This relay of commands would have been carried out by four of the supernumeraries attached to each syntagma of the pike formations: the herald (stratokērux – στρατοκῆρυξ), the aide-de-camp (huperetēs – ὑπηρέτης), the standard bearer (semeiphoros – σημειφόρος), and the trumpeter (salpigktēs – σαλπιγκτής).

According to the Suda, it was the role of the herald to relay orders by voice.¹³⁸ During a battle, each officer above the rank of syntagmatarch, in command of their respective unit or sub-unit within the broader formation of the pike-phalanx, would have the aid of a herald. Thus, if the preconceived battle plan required the unit to conduct a particular movement such as an advance, a feigned withdrawal or a counter-march when either a certain point in time was reached or a certain criteria was met, the commander, once that moment had arrived, could instruct his herald of the new order who would then call it out so that it could be heard by the men in the unit. At Gaugamela, part of Alexander’s standing instructions was for his troops to obey orders quickly.¹³⁹ This shows that, even though a pre-conceived battle plan may have been formulated, parts of it were either not put into effect immediately once the battle had begun, and/or that, due to the many variables of combat, plans could change and new orders issued at a moment’s notice.¹⁴⁰

If any such an operation was conducted by a relatively large unit, such as a merarchia, it is highly unlikely that the voice of the herald standing next to the merarch would carry far enough to be clearly heard by every member of the larger unit – even without the din of battle being considered. As such, an instruction announced by the commanding officer’s herald must have been relayed across larger units by the other heralds within it. Due to heralds being attached to each syntagma, this would mean that each instruction would only have to be passed a distance of 16m from one herald to the next. Even if a phalangite on the far side of his syntagma did not hear the order called out by his respective herald, he still would be in a position to hear the instructions as it was relayed by the herald attached to the adjacent unit. This, in part explains why the supernumeraries were attached to the syntagma rather than a larger unit and why this unit was the smallest tactical formation of the phalanx.

Under such circumstances silence was paramount. Aelian and Arrian devote entire sections of their examinations of the phalanx to the importance of silence within the ranks so that such orders could be heard.¹⁴¹ At Gaugamela, Alexander ordered his troops to advance in total silence and to only raise their warcry in unison when ordered to do so.¹⁴² This would have ensured that any instructions given up to that point would have been easily heard and promptly followed as the sheer size of the formations involved caused considerable problems for the relaying of information. Appian states that one of the problems of large armies is that they are often so big that people cannot see what is going on and if one section of the line gets into difficulties, the news of this trouble is intensified as it is transmitted down the line and this can lead to a general panic forming.¹⁴³ The avoidance of such potential calamities explains why Hellenistic armies employed a whole range of methods to pass information and instructions between commanders and their units.

Verbal instructions could also be delivered by a runner. This was most likely one of the roles of the aide-de-camp. The Suda states that the role of this supernumerary was to ‘carry over some of the things that are needed’.¹⁴⁴ The most likely form of these ‘needed things’ would have been the delivery of information. At the Hydaspes, the units of Meleager, Attalus and Gorgias were instructed to cross the river as separate units.¹⁴⁵ It is unlikely that Alexander personally delivered such instructions, although it cannot be ruled out that they were part of the already disclosed pre-conceived battle plan. Rather Alexander would have relayed these orders to the individual unit commanders via a runner and these orders would then be passed down through the respective formations. Arrian describes this in his account of the battle itself. Once across the river, Alexander is said to have ‘ordered the infantry to follow in good order and at a marching pace…He directed Tauron, the commander of the archers, to lead them on with the cavalry, also at full speed.’¹⁴⁶ Once the fighting had commenced ‘Coenus was sent to the right…and ordered to close with the barbarians from behind…[and] Seleucus and Antigenes and Tauron were put in command of the infantry phalanx, with orders not to take part in any action…’.¹⁴⁷ Again, it is unlikely that Alexander, who was himself engaged on the right of the line, would have delivered all of these instructions personally and would have used a series of messengers to deliver the orders.

Many of the pike units themselves seem to have had a considerable amount of command autonomy on the battlefield, especially at the higher levels. At Granicus, the units of Alexander’s right wing wheeled to the left to strike the Persians in the flank. Such a manoeuvre could have only been undertaken if the commanders of each of the two merarchiae involved had co-ordinated with each other, most likely through the use of orders delivered by runners, the exact moment that this change in direction was going to take place. Had both units not co-ordinated their movements, they ran the risk of entangling with one another, possibly as one unit continued to advance while the other wheeled, or of one unit being left dangerously exposed while the other changed its path. At Gaugamela, Parmenion, in command of the left wing, also sent messengers to Alexander to inform him that the position was becoming hard pressed.¹⁴⁸ This not only demonstrates the use of messengers and runners to relay information and requests for assistance across the battlefield, but that some of these messengers were highly mobile, possibly mounted, and could cover considerable distances to locate specific individuals amidst a battle containing thousands of men. All of this combined to make the pike-phalanx, and pike-phalanx tactics, rather fluid and adaptable.

Yet, across the din of battle, general instructions such as the order to advance or retreat may not be heard for any number of reasons. This was where the other supernumeraries attached to each syntagma, the standard bearer and the trumpeter came into play. The positioning of standards across the front of the pike-phalanx could not only be used to help the formation retain a relatively level frontage, as Curtius states they were used for at Gaugamela, but could also be used to relay orders to the troops of their respective units.¹⁴⁹ The Suda states that one of the functions of the standard bearer was to relay orders ‘by the standard, if the voice is not heard because of noise [of battle]’.¹⁵⁰ Thus the role of the standard bearer was to facilitate the issue of commands by delivering them visually. It can only be assumed that, when a unit received such instructions, they were relayed both verbally by the herald and simultaneously visually by the standard bearer so that each member of the unit would have a chance of receiving the orders in at least one form.

This, in turn, suggests that there was a standard set of drill movements and actions that the standard bearer could perform and that the meaning of these instructions was easily recognizable by every member of the unit. Unfortunately, none of the extant literature outlines what these drill movements or actions were. However, it must be concluded that there was an action (or series of actions) which translated into every basic command that a unit might be given – raise pikes; lower pikes; advance; halt, wheel, counter-march and so on – otherwise the standard bearer would have limited value to the command structure of the unit.

As with the herald, because there was one standard bearer attached to each syntagma of the phalanx, the signal that was given needed only to have been visible from a distance equal to the diagonally opposite side of the unit – a distance of some 20m. Even if those on the far side of the unit were unable to see their respective standard bearer due to dust, smoke, rain or any other visual impediment, they might have still been able to see the standard belonging to the adjacent unit, or simply relied on the verbal outbursts of the herald for their instructions.

Furthermore, there had to be both a verbal command and a visual signal which signified that the command that was to follow was for a specific unit to avoid confusion. For example if the men on the far side of one syntagma could not see their standard nor hear their herald, but the adjacent unit was given the order to advance while theirs was not, those men could not simply follow the orders relayed by the supernumeraries of the adjoining unit lest they incorrectly obey an order that was not meant for them. This suggests that each order that was relayed was preceded by a call and/or signal which alerted the men of the required unit that the information that was to follow was for them, and for them alone. Regardless of whether this was for a sub-unit such as an individual syntagma, or was an order that governed an entire merarchia but was being relayed to each sub-unit within it, as each successive unit was forwarded the command, the men inside it would have had to have been alerted that an order was coming.

Standards and banners, in a variety of forms, relayed information at all levels in battles across the breadth of the Hellenistic Age. Pyrrhus’ army at Asculum in 279BC, for example, employed a series of ‘hoisted signals’ to relay instructions.¹⁵¹ Standards were also used in the army of Philip V at Athens in 200BC and by the army of Antiochus III at Thermopylae in 191BC.¹⁵² At Sellasia in 222BC, Antigonus himself began the attack by raising linen and scarlet flags to order different wings of his line to advance.¹⁵³ Polybius says that, once these signals had been given, the officers commanding the appropriate units then relayed these instructions down to their men.¹⁵⁴ This not only illustrates the use of other means for the officers of each unit to relay the order to advance, but also that a pre-conceived plan had been put into effect, most likely determined at a pre-battle council, where the officers were informed of what to do once the flags had been raised.

Yet under certain conditions neither the cries of the herald, nor the signals of the standard bearer, could be heard or seen. This was where the last of the supernumeraries – the trumpeter – was used.¹⁵⁵ As with both the herald and the standard bearer, commands issued for each unit would have been delivered though a variety of different trumpet blasts to relay specific orders. Thus, like the standard bearer, there must have been a certain set of blasts (or series of blasts) each of which translated into a specific command that was readily understood by each member of the phalanx. Additionally, and also like the standard bearer, there must have also been a set of specific notes that could be played to alert individual units to the incoming orders. Polybius states that at Sellasia a contingent of light troops was recalled by the sounding of a trumpet.¹⁵⁶ This indicates that there was a preliminary blast to alert just the light troops to the incoming order as, had the trumpet call simply meant ‘withdraw!’ any unit may have followed the order.

Other, more general orders, seem to have been able to be delivered by trumpet as well. Alexander’s army, for example, was ordered to both attack and withdraw at Halicarnassus in 334BC, Issus in 333BC, Gaugamela in 331BC, and at the Hydaspes in 326BC, by the sound of a trumpet.¹⁵⁷ The entire army of Eumenes was recalled ‘with the sound of the trumpet’ at the Hellespont in 321BC, as was Polyperchon’s army at Megalopolis in 318BC.¹⁵⁸ Demetrius’ army was similarly recalled ‘by a trumpet call’ at the Nabataean Rock in 312BC.¹⁵⁹ At the battle of Beth-Zachariah in 162BC, the signal for the whole Seleucid army to advance into battle was given by the blast of a trumpet.¹⁶⁰ Such passages show the use of trumpeters to relay commands across the entire Hellenistic Period. Undoubtedly these instructions would have been passed among the units by their various trumpeters and more than one ‘sound of the trumpet’ over the entire execution of the command must be assumed.

This leads to the question of the advance itself; once the signal to advance had been given, how fast did the phalanx actually move and how was this pace maintained so that the cohesion of the line was not lost? Sheppard suggests that the advance of the phalanx was sometimes conducted at the run.¹⁶¹ Adcock, on the other hand, offers that the phalanx relied more on a steady advance than it did on a rapid charge.¹⁶² Pietrykowski suggests the phalanx advanced at the ‘quick step’.¹⁶³ In modern military terminology, this equates to a rate of around 120 paces per minute – with each pace being about 75cm in length (from heel to toe).¹⁶⁴ If this is the rate of march that Pietrykowski is referring to, it would seem a bit quick for a formation of men encumbered with heavy armour and carrying a 5kg sarissa who were trying to maintain a compact formation.¹⁶⁵ When the maximum possible rate of march was tested using small groups of re-enactors equipped as phalangites, it was found that it is almost impossible to maintain any semblance of order within the ranks when the formation is moving at anything other than a brisk walk. This would suggest that a slightly slower pace would have been used by much larger pike-phalanxes.

Indeed, there are only few accounts in the ancient literature where the phalanx seems to have moved at anything like a running pace. One instance of a rapid advance occurred at Cynoscephalae in 197BC.¹⁶⁶ Yet even here this advance was to move troops into position quickly, and to seize high ground, rather than an actual advance into combat. The pike units on Alexander’s right wing at Gaugamela are also said to have advanced against the gap in the Persian lines at the run (δρόμῳ).¹⁶⁷ However, it is unlikely that a rapid rate of march could have been conducted in a manner which would allow the pike formation to be maintained. Consequently, it is more likely that the Macedonians advanced at a brisk trot at best rather than a flat out run. In a clear instance of a rapid advance into contact, at Massaga in 327BC, Alexander’s phalanx was said to have counterattacked ‘at the run’. However, even here Arrian states that ‘the mounted javelineers, the light armed Agrianians and the archers first raced forward and joined battle while Alexander himself kept the phalanx in formation’.¹⁶⁸

This suggests that, not only is the term ‘phalanx’ being used here in its generic sense to mean ‘army’, but also that the pike units were brought into action at a slower pace than the lightly armed troops to maintain their cohesion. This is also likely what happened at Gaugamela where the gap in the Persian line was assaulted by cavalry at the charge (hence the use of a term meaning to ‘run’ or ‘advance quickly’) with pike units moving up in support but more likely at a slower pace to maintain their lines. Additionally, it would have taken a short amount of time for Alexander’s phalanx at Massaga to conduct another counter-march and advance upon the enemy in their proper order – more time than would be required for the cavalry and light troops who could simply turn about. This again suggests that the pike units advanced more slowly.

Other passages suggest that a rather rapid advance of the phalanx was possible. At Chaeronea, for example, Philip’s phalangites delivered a ‘committed attack’.¹⁶⁹ At Gaugamela, Alexander’s phalanx ‘rolled forward like a flood’.¹⁷⁰ At Pydna, the Macedonians are said to have attacked so swiftly that the first Roman was killed not far from his camp.¹⁷¹ While all of these accounts clearly describe an advance of the pike-phalanx that was seemingly quite rapid, none of them specifically state that they were conducted at a running pace and a simple fast walk cannot be discounted. It can also not be discounted that these descriptions are of the ferocity of the attacks made at Chaeronea and Gaugamela, rather than their speed, and that the cause for the seemingly rapid attack at Pydna was in part due to the unpreparedness of the Romans. Furthermore, it is possible that the descriptions of the running move of the phalanx up the ridge at Cynoscephalae are merely a literary motif, utilizing a description of something that the pike-phalanx rarely did, to emphasize the seriousness and urgency of the situation. This in itself would suggest that the pike-phalanx advanced into action at a much slower pace.

The few ancient passages that provide more details of the movement of the phalanx all suggest that the formation was moved at a slow pace that would allow the line to be maintained. Arrian, for example, states that, at the battle of Issus ‘[Alexander] was leading [his men] still in line… step by step so that no part of this phalanx should vary and break apart [as it would] at a quicker pace’.¹⁷² Even formations of more mobile hoplites in the Classical Age rarely charged at the run and, as Arrian states, it would be almost impossible to maintain a formation of thousands, or tens of thousands, of men armed with lengthy pikes at such a speed.¹⁷³ Julius Africanus, in a reference to the combat of the Classical Age, states that ‘running in hoplite equipment was infrequent and not prolonged; it is instead quick and of the sort that might be used when one is in a hurry to get inside the trajectory of an arrow’.¹⁷⁴ It can therefore only be assumed that variations of a ‘quick-step’ pace, and possibly one of a slower ‘halfpace’, were used to keep the phalanx (both Classical and Hellenistic) together depending upon things like terrain and the tactical necessities of each situation.

Philip II’s feigned retreat at Chaeronea, for example, if accomplished by having his pike units march backwards, rather than having them conduct a counter-march, could have only been done at a slow pace so that the formation could be maintained, and the pikes kept presented, while the unit moved back and uphill away from an advancing enemy.¹⁷⁵ Alexander is said to have conducted a similar feigned retreat at Massaga in 327BC but, according to Arrian, this manoeuvre was clearly undertaken using a counter-march rather than by marching his phalanx backwards.¹⁷⁶ At Magnesia in 190BC the phalanx formed a defensive hollow square, with light troops and elephants positioned in the centre, and attempted to withdraw ‘step-by-step’.¹⁷⁷ Appian specifically states that the defensive square was arranged in an intermediate-order and that thickly set sarissae projected from all four sides of the formation.¹⁷⁸ Parts of this square would have been definitely marching backwards and a slow pace would have certainly been used to keep the formation together.

The ability for the phalanx to advance or retreat with relative ease and still maintain the integrity of their formation also demonstrates that the side-on posture suggested by some scholars for how the sarissa was wielded, and the close-order interval of 48cm per man, could not have been used within the pike-phalanx. When standing side-on it is impossible to move at anything faster than a shuffling side step. While this could be used for a slow advance, it could not be used for anything more rapid and the inability of the weapons of the phalanx to be deployed while in a close order would simply be compounded if the formation was attempting to move forwards or backwards at the same time. Thus it seems clear that the pike-phalanx operated on the battlefield with its members wielding the pike using an oblique body posture, within an intermediate-order interval of 96cm per man, and moving at a brisk walk at the very best.

The pace of the march could have been maintained through the use of a cadence of some kind. Hoplite armies of the Classical Age regularly used a chanted ‘marching song’ (ἐμβατήριος παιάν), or paean, to keep in step and hold the formation together, just as many modern armies do.¹⁷⁹ While there are no specific references to the army of Alexander using the paean, and Aelian emphasizes the importance of silence within the phalanx, Alexander’s order to advance in silence at Gaugamela suggests that on occasion the phalanx could be quite boisterous. This suggests the use of a sung cadence at times, and the references to units or phalanxes moving ‘step-by-step’ additionally suggest the use of a cadence of some form.

If a called or sung cadence was not used, another possibility is that a musical one was. Again, hoplite armies of the Classical Age were regularly accompanied by musicians, whose beats played on anything from drums to trumpets to pipes and lyres, helped keep the formation in step and maintain the phalanx’s cohesion.¹⁸⁰ The trumpeter attached to each syntagma of the Hellenistic pike-phalanx could have similarly been used to blast a series of short notes at regular intervals to help keep the formation moving at the desired measured pace. If a new order was received, which then needed to be passed on to the men of the unit, the trumpeter could simply halt the playing of the cadence and deliver the instructions. The brief cessation of the blown cadence would have the added benefit of alerting the men within earshot that another order was about to be relayed.

Dickinson claims that, apart from wheeling, there is no evidence for intricate drill movements being made by Alexander’s phalanx.¹⁸¹ However, the literary evidence shows that the phalanx was capable of varied and detailed movements, both in the time of Alexander and the later Successors. Furthermore, it is clear that the use of the herald, the standard bearer, the aide-de-camp and the trumpeter as means of delivering instructions and to maintain the formation, allowed the commanders of pike-phalanxes to carry out the details of any battle plan, adjust them when necessary, and adapt the flexible units of the pike-phalanx to the changing nature of the battlefield, both easily and with a certain level of sophistication.

Once the phalanx had been deployed in its proper order and configuration, the weapons held by the individual phalangites had to be positioned in order to engage an opponent. Polybius details how phalangites were given orders to ‘lower pikes’ (καταβαλoῦσαι τὰς σαρίσας).¹⁸² The order to lower pikes is also contained in a list of general drill commands found in the military manuals.¹⁸³ Both Polybius and the manuals also outline how the weapons of the forward ranks of the phalanx projected ahead of the line once they had been lowered for combat.¹⁸⁴ Polybius calls this arrangement a ‘closely packed [hedge] of pikes’ (συμφράξαvτες τὰς σαρίσας).¹⁸⁵ Livy similarly describes the phalanx as ‘closely packed and bristling with extended pikes’.¹⁸⁶ Plutarch says that the pikes of the phalanx were ‘set at one level’ (ταῖς σαρίσαις ἀφ’ ἑvὸς συvθήμaτος κλιθείσαις).¹⁸⁷ But how were the pikes of the phalanx actually arranged once they had been lowered and set in position? It all depended upon how the file itself was configured.

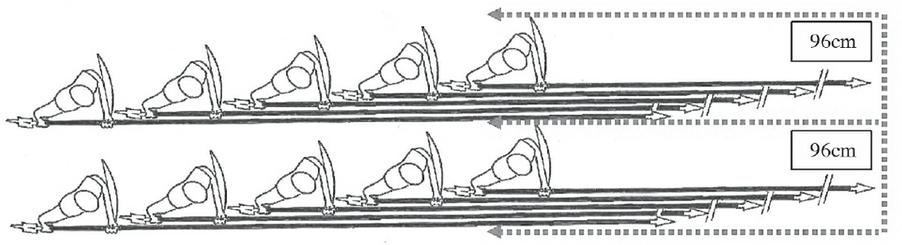

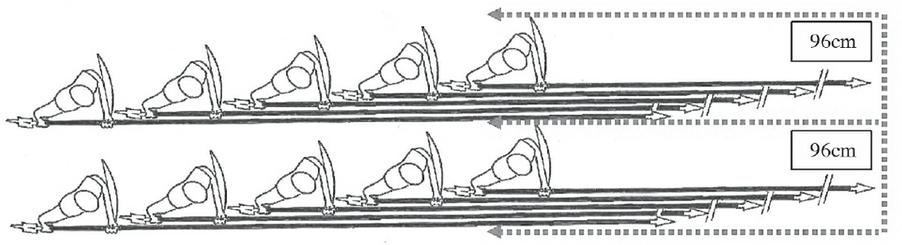

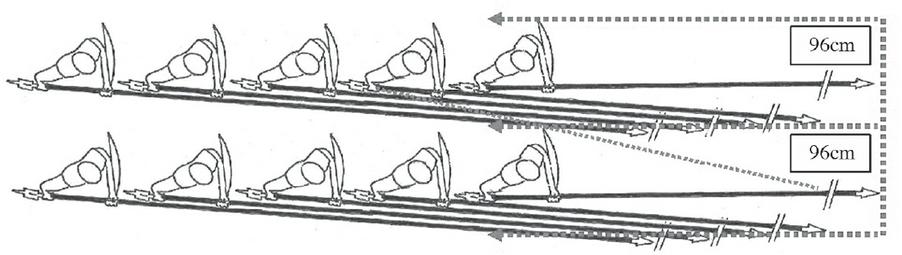

The vast majority of modern works which examine the warfare of the Hellenistic Age contain passages and/or diagrams which show the members of each file of the phalanx with their pikes lowered and parallel with each other. This seems to be a commonly accepted convention amongst scholars and no analysis of other possible configurations, or of the further implications of such arrangements, seems to have been made other than presenting a generalized statement on the matter. Fuller, for example, simply states that ‘the phalangite wielded his sarissa with both hands, keeping it carefully aligned with the weapons of his comrades’ (Fig. 50).¹⁸⁸

Fig. 50: The first five members of two files with their pikes lowered parallel to each other.

Such an arrangement of the file conforms with the use of the 96cm intermediate-order interval outlined in the military manuals for how the phalanx was configured. Plutarch’s description of all of the lowered weapons of the phalanx being ‘set at one level’ indicates that those weapons that were presented for combat were side by side and not positioned one above the other and the arrangement of the men in the file with their pikes held parallel to each other conforms with this description. This, in turn, means that the phalangites of each adjacent file could not have moved closer to each other and, as such, the intermediate-order was the smallest interval that the phalanx could adopt while still being capable of movement with relative ease and of presenting an offensive posture (see: Bearing the Phalangite’s Panoply from page 133). Such an arrangement also has other implications for understanding the internal structure of the pike-phalanx.