Seeing and Not Seeing

I first encountered the Bengali Goddess Kālī in her dressing room—the workshops where she is prepared from straw and clay for her annual Pūjā—in November of 1989.1 I was making my first visit to Kumartuli, the section of northern Calcutta where many of the city’s professional image makers (Kumārs) have their studios. This was also my first adventure with Jeffrey Kripal, a new friend and colleague in the study of Bengali Śāktism. We were guided by Aditi Sen, of the American Institute of Indian Studies, a friend and mentor to us both.

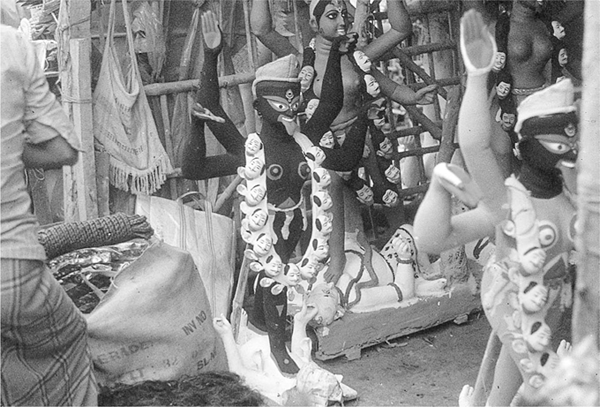

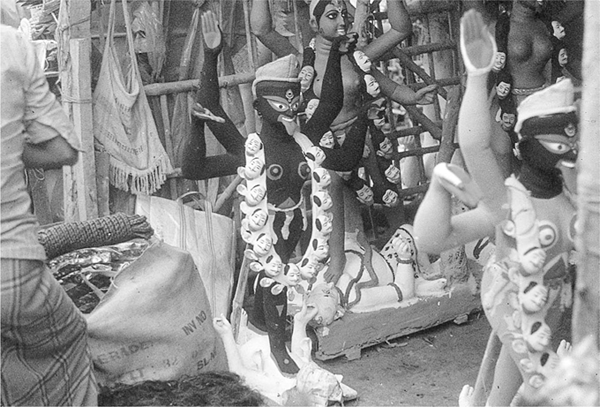

Jeff, Aditi, and I meandered through the alleyways of the artisans’ district, gazing at the many images (pratimās) of Kālī that awaited completion by their creators. Some were no bigger than a foot high, while others were so tall that painters had to perch atop ladders to design their faces. Some showed evidence of the straw innards underneath their drying clay molding, whereas more finished Kālīs glistened with the sheen of fresh paint and tinsel decorations. But as Jeff and I stared delightedly at these evolving figures, we noticed that there were two different types of Kālī images under production (fig. 6.1). The types had similar bodies, with shapely women’s curves, large round breasts, the right foot firmly planted on the chest of prostrate Śiva, and her four arms holding the traditional items (a cleaver [khaḍga] and severed head in her two left hands, and fearlessness- and boon-conferring hand positions [abhayā and varadā mudrās, respectively] displayed by her two right hands). The two types were also decorated in a comparable fashion, with paint, long black hair, ornaments, and clothes. The main differences concerned their colors and faces. To be sure, the black Kālī’s face was anthropomorphized, but the eyes were much larger than a human’s, and the requisite lolling tongue was distended below the chin to the point where the neck meets the torso. Her smile was hard to discern, and the overall effect, before clothes and decorations had somewhat modified it, was formidable. The visage of the blue Kālī, on the other hand, was modeled on a human woman’s face; the features were normal in size, the tongue was short, extending to slightly above the chin, and the upturned corners of the mouth formed an obvious smile.

FIGURE 6.1. Two types of Kālī. Kumartuli, Kolkata, November 1989. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

Jeff and I were puzzled by the disparity in these two depictions, but we had no time to inquire about their origins, meaning, or comparative popularity. Nonetheless, this initial glimpse alerted me to the multifacetedness of the Goddess’s iconographic traditions, and set me on a quest for further understanding. I stayed in Calcutta over eight Kālī Pūjā celebrations (1989, 1991, 1995, 1996, 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2001), during which time I saw and photographed hundreds of Kālīs, and interviewed many artisans and scholars knowledgeable about their iconographic development. In the years since that first trip to Kumartuli, I have also become fascinated by other aspects of Kālī’s history in Bengal: the upsurge of interest in Tantric rites and texts after the fifteenth century; the place of Kālī worship in the political and social consciousness of the landed gentry in the medieval and early modern periods; their avid patronage from the eighteenth century of new Śākta vernacular literatures; Kālī temple construction; and Kālī Pūjā festivities. It is now clear to me that all such features of Kālī’s involvement in the Bengali environment are pertinent to the understanding of her iconic portrayal.

It is my aim here to relate, I believe for the first time,2 a connected narrative about the evolution of Kālī’s iconography, tying together artistic, literary, religious, social, and political history—with a special emphasis on the relationship between the festival pratimās and the Goddess’s Tantric roots. This is a story unique to Bengal and—of late—to its West Bengali geographic locales; it describes Tantra on Bengali ground. Furthermore, it tells of revelations and concealments, meanings explicit and implicit, and the ironies of human motivation. To return to Kumartuli and our visit there in 1989, I now realize that Jeff and I had eyes discerning enough to identify fewer than half of the differences between the two types of Kālī figure. However, to have been so long unseeing only adds to present delight.

The Tantric Goddess Comes Forth

“Equipped with Tantric Paraphernalia:” Kālī in the Eleventh to Fourteenth Centuries

Although Kālī as a goddess has been known at least since the Epics and early Purāṇas,3 she begins to gain her characteristic Bengali iconic form4 and association with Tantric rituals beginning from around the eleventh century. Popular opinion assigns the creation of the modern Kālī image to the seventeenth century, with Kṛṣṇānanda Āgambāgīś and his famed vision of a servant girl slapping dung on a wall, which he saw as the promised revelation of Kālī’s form. However, Kālī’s iconography certainly predates Āgambāgīś; not only did he himself quote earlier Tantric descriptions of the Goddess’s appearance in his Tantric digest, the Tantrasāra, but we have independent corroboration from other texts and relics that at least from the eleventh century Kālī had been envisioned in terms very similar to what one sees today. To give just a few examples, the tenth- or eleventh-century Mahābhāgavata Purāṇa, the eleventh-century Devībhāgavata Purāṇa, and the thirteenth-century Bṛhaddharma Purāṇa (all written in Bengal or by Bengalis) describe Kālī in several places as a naked goddess with big teeth, a lolling tongue, a garland of cut heads, four arms, a corpse seat, and a covering of blood;5 and both the twelfth-century Kulacūḍāmaṇi Tantra and fifteenth-century Kālī Tantra are sources for some of Kālī’s dhyānas (descriptions used for Tantric meditation on the deity in the heart).6

Kālī’s early origins in eastern India can also be proven by her incorporation into Tantric ritual. Teun Goudriaan claims the early-thirteenth-century Yonigahvara as the oldest text on Kālī worship; its instructions on Tantric meditation, heroic rites, and heterodox practices all involve Kālī.7 By the time of Brahmānanda Giri and his pupil, Pūrṇānanda Giri, from the Dhaka region in the early and late sixteenth century, respectively, their rival Kṛṣṇānanda Āgambāgīś, also from the late sixteenth century, Raghunāth Tarkabāgīś Bhaṭṭācārya, in the late seventeenth century, and Rāmtoṣaṇ Tarkabāgīś, of the early nineteenth century, Kālī had become an important component of Śākta religious practice (sādhanā) and praise verse (stuti).8

Thus one must agree with Pratapaditya Pal, who argues that it was between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries that Kālī came to be worshiped with “all sorts of [T]antric paraphernalia,” such as skulls, corpses, and instruments of death, and who sat or stood on a corpse identified as Śiva.9 Evolving, therefore, from a fairly minor deity in the world of the Epics and earlier Purāṇas, Kālī makes her splash in Sanskrit literature in the first half of the second millennium as a deity of life, death, transformation, and ritual. While still shared by both Purāṇas and Tantras, she is primarily a Tantric deity, for she develops few myths or stories, except by association with Pārvatī, and her primary appearances occur in the context of instructions to spiritual adepts, or sādhakas.

An additional difference in these Purāṇic and Tantric portrayals of Kālī appears in a detailed examination of the Goddess’s dhyānas. Of the nine dhyānas reviewed here—six from Tantric and three from Purāṇic texts10—all refer to Dakṣiṇākālī as: terrible or frightening (karālā, bhayaṅkarī); toothy; naked; endowed with four arms holding the usual items; and adorned with a necklace of freshly severed, blood-dripping heads (muṇḍamālā) and a skirt of amputated arms, sewn together at the elbows. Other features of her iconographic portrayal include black skin color, disheveled hair, three eyes, a lolling tongue, a mouth that is both drinking and dripping blood, babies’ corpses dangling from her ears, a proclivity for quaffing liquor and bellowing horrid shrieks, and a preference for cremation grounds, where she wanders with her jackal and yoginī friends. Most of these dhyānas attempt to attenuate the off-putting nature of this Goddess by stressing her boon- and fearlessness-conferring hand gestures, her gorgeous smile, the crown and/or half-moon perched upon her head, the serpentine sacred thread draped around her torso, and her heavy, uplifted breasts.

What is intriguing to me about these dhyānas is their uneven references to Kālī’s activities with Śiva. Prior to the fourteenth or fifteenth century, Kālī may have been seated on Mahādeva in the form of a corpse, but there was nothing sexual about their interaction; he was just a seat. This Purāṇic and even early Tantric vision of the pair changes with the most famous of Kālī’s meditational images, from the Kālī Tantra, where the word viparītaratā is introduced to indicate that Kālī and Śiva are “engaged [in intercourse] in the reversed position,” with the female on top in a seated pose. This emphasis is repeated in later Tantric dhyānas from the Svatantra Tantra, the Mantramahodadhiḥ and the Āgamatattvavilāsa—an indication of Kālī’s growing importance to the sexualized philosophical and ritual Tantric context.

It is important to remember that these dhyānas were for meditational purposes only. The Tantric adept was to worship the Goddess in his heart; the construction of an actual image out of stone or clay was not the ideal. It is true that he was to invite her to step out from his heart into the specially prepared yantra, or mystic diagram, which he had created in front of him in order that he might make offerings to her, but her origin and form were always of the heart.11

Thus, Kālī’s presence in the world of Sanskrit ritual as practiced in eastern India began in the early centuries of the second millennium C.E., and she gained increasing attention over time in Tantric manuals, digests, and compendia. But she was principally a deity of the tutored elite, and the details of her appearance derived from and were germane to the largely esoteric arena of Tantric ritual and power. It is not until the seventeenth century that this Goddess of meditation and heterodox rite took her first steps out into the vernacular, popular world.

Looming Larger: Kālī’s Vernacularization and Popularization in the Seventeenth to Eighteenth Centuries

Much has been written about conditions in Bengal in the late medieval period: the revival from the time of Caitanya in the fifteenth century of Vaiṣṇava religiosity, which led the older Śākta and Tantric lineages into creative strategies of accommodation and rebuttal; the opportunities for expansion and frontier building under the Mughals; the rise of landed estates headed mainly by Hindus of a Śākta persuasion, who used Śākta symbols in the service of their own aspirations to power; after the arrival of the British in the seventeenth century, the new occasions for political and social jockeying among Bengalis, Mughal rulers, and British adventurers; and finally, in the eighteenth century, tremendous social upheavals emanating from famines, Mārāṭhā raids, and the burden of increased taxation. Such religious, social, and political contexts provide the backdrop for how the Goddess Kālī emerged from her narrow Tantric enclave and became accessible to a wider audience in this period: (1) the spate of Tantric texts, sometimes with Bengali translations, available from the sixteenth century; (2) Kālī’s entrance into two new vernacular literary genres, that of the Maṅgalakāvyas from the seventeenth century and the Śākta padas from the eighteenth; (3) the construction of many new goddess temples, also from the eighteenth century; and (4) the development, again in the eighteenth century, of the yearly Kālī Pūjā.

Why the sudden flowering of these literary and religious venues for the worship of the Tantric deity? Why the urge to make Kālī more publicly recognizable and accessible? Two answers suggest themselves again and again in the literature: the influence of, or threat from, the increasingly prominent Vaiṣṇava community; and the obvious “fit” between the martial imagery of the Goddess of power and the royal ambitions of the elite class of Hindu zamindars, who sought to legitimate their expanding social and religious status through Śākta symbolism.

THE PROLIFERATION OF TANTRIC TEXTS Take, as an example, the outpouring of Tantric texts and digests from the seventeenth century onward, many of which are repositories of thought on Kālī’s significance, ritual worship, and iconography. While scholars disagree as to the positive or negative valence of the interaction between Śāktas and Vaiṣṇavas after the time of Caitanya—some arguing that the relations were friendly and others that they were antagonistic12—it cannot be denied that the popularity of Vaiṣṇava literature spurred many Śākta writers into action. A new genre of Tantric texts was created to marry Vaiṣṇava and Śākta interests, stories, and rituals,13 and Kṛṣṇa found a favored place even in the Śākta Tantric compositions. Pratapaditya Pal notes that Āgambāgīś’s real reason for writing the Tantrasāra was to make more public those goddess traditions which were under threat of being lost in the wave of enthusiasm for Kṛṣṇa.14

Moreover, many of these Tantric ritual texts were written either by members of the landed gentry or by retainers and scholars under their patronage. Appendix I of S. C. Banerji’s Tantra in Bengal lists 97 unpublished Bengali Tantras. All of these for which there are dates derive from 1605 to 1843, and all of the writers are landlords or their proteges.15 One can make the same argument by glancing at the history of the Śākta poetry, which gains prominence with Rāmprasād Sen in the middle of the eighteenth century: everyone who composes in the genre, until well into the late nineteenth century, is associated with the largely Śākta-leaning aristocracy.16

KĀLĪ IN MEDIEVAL MAṄGALAKĀVYAS AND EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ŚĀKTA POETRY The second indicator that Kālī was becoming more noticeable in Bengali contexts is her inclusion in the genre of medieval Bengali Maṅgalakāvya poetry. This forms the bulk of middle Bengali epic poetry, probably derived from an earlier, oral tradition used as part of ritual worship,17 and represents popular, non-Brahmanical religiosity during the Sultanate period in Bengal.

The Kālikāmaṅgalakāvyas, which glorify Kālī, are noteworthy on several counts. First, unlike the case for Durgā, Caṇḍī, and Manasā, there is nothing at all written on Kālī in the vernacular until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when Bengalis started incorporating her into the Maṅgalakāvya genre. Second, one can see the growth of Kālī in Bengali devotion by looking at her increasingly prominent role in the poem’s main love-story about Vidyā and Sundara. Carol Salomon compared the Vidyā-Sundara sections in the twenty-three extant Kālikāmaṅgalakāvyas and discovered that whereas in the early versions Kālī has a minor, almost cosmetic role, in the later renditions, from the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, she directly intervenes in the story, moving the plot through her appearances and boons.18 Third, the Kālikāmaṅgala authors tend to sweeten and decorate the fierce Goddess, in a fashion similar to the earlier Sanskrit Tantras. While being described as grotesque, with a distended tongue, a garland made of severed heads, matted hair, and a tiger’s skin around her waist, deafening the atmosphere with her stamping thuds and raucous laughter, she is also painted with endearing language: her corpse earrings are decorated with jewels; she wears ankle bracelets with tinkling bells; gold and jewels cover her entire body; the crescent moon adorns her hair; and she stands in the charming three-bends tribhaṅga pose, like Kṛṣṇa.19 Here we have evidence, therefore, that the iconography of the slowly vernacularizing Kālī is in direct continuity with her Tantric past.

The Kālī of the Kālikāmaṅgala gives way, by the eighteenth century, to the Kālī of the Śākta padas, short lyrical poems of praise, petition, and complaint set to music and sung to the Goddess, now addressed as Mā, or Mother. This Kālī is still the cremation-ground wanderer of the Tantric dhyānas—many of the poems are Bengali transcriptions of the Tantric portraits of the deity, with a few petitionary lines added at the end—but she is also the one who can be teased, berated, pouted at, and threatened by her poet, who approaches her in a spirit of devotion (bhakti).20 Rāmprasād Sen, who may be considered the earliest exponent of the new Śākta poetry tradition, also wrote a Kālikāmaṅgalakāvya—proof of the literary transition from one genre to another.21 It is likely that the biggest impetus for the switch from the narrative Maṅgalakāvya style to that of the short, distinct padas was the influence of Vaiṣṇava Padāvalī and its pathos-filled descriptions of the love between Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā. Śākta poetry mirrors the rhythm patterns, refrains, and signature lines (bhaṇitās) of its Vaiṣṇava counterpart, as well as its imagery. Ways of describing Rādhā’s beauty are borrowed for Kālī, who, say some Bengali literary critics, is touched by the Vaiṣṇava sentiment (rasa) of sweetness (mādhurya); it is thus that she becomes the loving, compassionate, and attractive mother.22 From the Vaiṣṇava literary world, therefore, the Śākta poets inherit both a style and a set of familiar formulae for indicating the divine–human relationship in all its emotional timbres.

While it is easy to detect the Vaiṣṇava influence upon the composition of Śākta Padāvalī, it is harder to determine who sponsored the inclusion of Kālī in the Maṅgalakāvya literature, and why. Nonetheless, it is clear why the Tantric Goddess sat so lightly in the medieval poetry but endured in her association with the padas: as a deity chiefly associated in her former Sanskrit life with rituals and meditation prescriptions rather than with a stock of stories, she was less amenable of enfoldment into the Maṅgalakāvya genre, which depended upon tales of gods and goddesses to popularize their worship. The padas, by contrast, inherited the rich tradition of Tantric images and praises, composed for personal devotion and spiritual enrichment.

ERECTING TEMPLES FOR KĀLĪ What the new Tantric compendia, Maṅgalakāvya stories, and Śākta poems were doing for Kālī in the literary sphere in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the construction of new temples was doing in the realm of ritual. It is hard to know just when external mūrtis for worship replaced or were added to less anthropomorphic representations of the devī, such as the pot of water. There is a tradition that this innovation originated with Rājā Kṛṣṇacandra Rāy, head of the Nadia zamindari from 1728 until 1782,23 but it is likely that the practice of creating goddess figures began several decades previously; the oldest Kālī temples date from at least the beginning of the eighteenth century.24 Moreover, the mention of Rājā Kṛṣṇacandra Rāy brings us back to a familiar point: the dedication stones of almost all surviving temples vouch for the involvement of zamindar patronage in the construction of goddess sanctuaries. The same rājās and rāṇīs who were sponsoring the writing of Tantric digests and Śākta poetry were also paying for the erection of temples in their lands. The zamindars of Nadia, Burdwan, Natore, and Dinajpur were especially prominent in this regard, but temple dedication was enthusiastically pursued by all men and women of means to authenticate their claims to piety and social concern.

FIGURE 6.2. The Kālī of Kālīghāṭ Temple. Kolkata, October 2002. Photo by Jayanta Roy.

The images in these old temples maintain something of the spirit of the Tantric dhyānas by portraying a goddess of fierce demeanor. Their stern faces are not very anthropomorphized, for they contain large, flaming eyes, huge teeth, and extended, long tongues. The Kālī of Kālīghāṭ, the most famous of all Kolkata’s Kālī temples, is a good example; she is shaped like a huge egg, with four tiny arms on the side, and her face assumes gigantic proportions relative to the rest of her. She has three eyes of equal size, shaped like elongated ovals, a small nose, a row of teeth, and a large golden tongue that hangs down her front (fig. 6.2).25

Other famed Kolkata Kālī temples house images that, though more anthropomorphized than the mūrti of Kālīghāṭ, nevertheless look quite formidable.26 Examples include the large-eyed Kālī at Phiringi Kālī Temple, which claims to date from 1498; Ṭhanṭhanīya Kālī Temple on College Street, built in 1704, where the image is very tall, with a large golden tongue, teeth, and big eyes; Siddheśvarīkālī Temple in Citpur (fig. 6.3), built in 1730–1731, in the back room of which is preserved the sword used for human sacrifice by the dacoits who first worshiped her; Dakṣiṇeśvar Kālī Temple, made famous by Rāmakṛṣṇa, who became a priest after the temple was opened in 1855 and who was intensely devoted to the black image with its big eyes and long red tongue;27 the Kālī at Nimtala Burning Ghat, called Śmaśānakālī or Ānandamayī, whose staring, large eyes and long, pointed tongue engulf the face; and the image at the Ādyāpīṭh Temple in north Kolkata, from 1926, which is naked and somewhat masculine in its features.28

FIGURE 6.3. Siddheśvarīkālī at the Citpur Temple. Kolkata, September 1998. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

Though it is not impossible that additional research might uncover some older, less fearsome Kālīs from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, such would not counter the generalized portrait of Kālī seen above. Indeed, Dīptimay Rāy, who traveled quite extensively throughout Bengal in order to prepare his 1984 book on sites associated with Kālī, says of a shapely, graceful image he found at the temple at Uluberiya, Howrah: “This type of charming, affectionate, and blissful image is very rarely seen in West Bengal. There is no sternness on the Goddess’s face; rather, it is as if she were suffused with pure bliss.”29 In addition to the iconographic prescriptions in Kālī-centered dhyānas, another reason for the fierce visages of many of these images is their associated lore; dacoits, temples amid dark woods, Tantric sādhakas’ five-headed meditation seats,30 and activities involving corpses on the cremation grounds are recurrent themes in the stories linked with numerous Kālī temples.

It is clear from the form taken by these early Kālī mūrtis that they are modeled directly on guidelines given in the Tantric dhyānas. Temple worship, then, is a concession to popular religiosity for those not sufficiently serious, well trained, or spiritually advanced for the internal techniques of mental visualization. The Tantras state unequivocally that offering food, water, and flowers to an image is the lowest form of pūjā; mantra repetition and meditation in the heart are higher stages along the path. An early-nineteenth-century Tantric compendium, the Prāṇatoṣiṇī, actively prescribes the worship of small images for householders, who are not ready to see the Goddess in less obvious forms, such as a woman’s genitals (yoni), a mystic diagram (maṇḍala), a sword, or a stone; these are the provenance solely of the adept.31

Thus, although the exact path from the internally conceived Kālī of Tantric ritual to the externally adored Kālī of temple worship is not easy to reconstruct in terms of motivations and dates, it is clear that the emergence of Kālī temples in the early eighteenth century was a third arena in which the Tantric Devī was issuing forth from her specialized, esoteric environment.

FÊTING THE GODDESS But there is a fourth route along which Kālī was invited to travel into the larger world: her annual Pūjā in the month of Kārtik (October–November), which began to be celebrated in the mid-eighteenth century. Although we will investigate Kālī Pūjā more thoroughly in chapter 7, it is appropriate to say a few words about it here, in terms of what we can glean about its influence on Kālī’s iconography.

Since all such Pūjā images were created expressly to be immersed after the cessation of the two-day festival, there are very few still extant from which to gauge what the Goddess looked like in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. One must rely on paintings, newspaper and travelogue descriptions, and even cartoons. An additional source is the Kalighat paṭs, or watercolors on paper, depicting gods and goddesses, animals and birds, and contemporary social events, which were popular in Calcutta from about 1800 until the 1930s.

All such clues, scanty though they may be, indicate that both temporary images and painted renditions of the Goddess were being created very much in the style of the then-permanent images—in other words, according to the pattern of the Tantric dhyānas. In a depiction of the immersion of a Kālī image, dating from 1808 and painted by Balthazar Solvyns, one can see that the image is naked, except for her flowing hair and necklace of cut heads, and that her face is fierce, with an upturned and distended tongue.32 Though not necessarily intended to portray temporary Pūjā images, paṭs also hint at what the nineteenth-century Goddess might have looked like; in one famous example, from 1875, Kālī is black, naked, adorned with her usual getup, and fierce, with a very long, pointed tongue.33

Nationalism also had democratizing effects on the Goddess. Although, as we have seen in chapter 2, it was generally not Kālī, but Durgā or Bhārāta Mātā, who galvanized the Bengali anti-British effort in the early twentieth century, Kālī’s bloodlust was occasionally used to stir up revolutionary fervor.34 One excellent iconographic example is an early-twentieth-century painting of the black Kālī standing on a white Śiva in the battlefield amid fleeing human demons.35 This irked the British, who saw it as anti-English revolutionary propaganda. However, as historians Partha Chatterjee and Lata Mani, among others, have ably demonstrated, the nationalist deployment of goddesses did not only draw upon their capacities for blood-letting and destruction. In seeking to protect and defend their besieged culture from the colonialist onslaught, Bengali nationalists essentialized “woman”—and, by association, deities like Durgā, Bhārat Mātā, and Kālī—as the feminine, maternal representation of the nation and its authentic cultural traditions.36 In the process, as I have argued in chapter 4, Hindu goddesses gained increasingly voluptuous, motherly personas, for they came to stand for the weak, weeping Motherland, ready to pour out their milk in gratitude for their heroic sons’ protection. One can see hints of these increasingly feminine, motherly iconic characteristics in the afore-mentioned painting. Kālī may kill demons, but her face is round and comely, and her body shapely.

Just how far Kālī had come by the early twentieth century is shown by these popular artforms: she is now a familiar vehicle for social and political commentary. Like the deity of the Śākta padas and established temple images, this Kālī of the public Pūjās, the cheap watercolor paṭs, the political spoofs, and the nationalist construction was a newly externalized representation of the Sanskrit deity of ritual practice, who had emerged into a more specifically Bengali, nonelite milieu in answer to theological and sociopolitical need.

“When Religion Is Joined to Beauty”: The New Realism of the 1920s and 1930s

After the breakthroughs of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the next major development in Kālī’s iconography occurs in the early twentieth century, with the transition from bāroiyāri to sarbajanīn Pūjās. In 1926, in the Bagbazar area of Calcutta, the ever-popular Durgā Pūjā entered its third phase. Kālī Pūjā followed suit in 1928,37 and within six years Kālī’s iconographical presentation had changed to meet the new demand for a publicly accessible goddess.

This is how it happened.38 For the 7 November 1934 Kālī Pūjā, N. C. Pāl, the same Kumartuli artisan who was so instrumental in altering Durgā’s image in a genuinely “Indian” or “Orientalist” fashion, also experimented with the conventions of Kālī’s traditional pratimā. He produced an image that was more realistic, human, and beautiful than ever before. As explained in more detail in chapter 4, Pāl was heir to the late-nineteenth-century Calcutta style of realism popularized in the mythological paintings of elite artists like Ravi Varma, M. V. Dhurandhar, and Bāmapada Banerjee. In her study The Making of a New “Indian” Art: Artists, Aesthetics, and Nationalism in Bengal, c. 1850–1920,39 Tapati Guha-Thakurta describes the evolution in Indian aesthetic taste during the course of the nineteenth century, when the evocation of volume and perspective and the lifelike appearances of people and scenes made a clean break from the earlier conventions of the Kalighat paṭs. Influenced by the colonizers’ distaste for native forms and divinities, Bengali artists refined their depictions of Hindu deities, so as to dignify their status and meet the standards of a new artistic ideal. Though Guha-Thakurta does not directly relate the changes she describes for painting to those in the Kumartuli Pūjā workshops, it is certain that the general move toward realism and beauty affected N. C. Pāl, a self-avowed admirer of Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951) and his student Nandalal Bose (1883–1966), of the Bengal School of Painting.

N. C. Pāl’s Kālī first appeared in the Thanthania area of northern Calcutta. Newspapers went wild with excitement, printing photos of and encomia about the new style. Still portrayed with her typical ornaments, stance on Śiva, lolling tongue, and disheveled hair, Pāl’s image departed from past models chiefly in the face and in the more realistic conveying of motion. First, her skin got lighter, from black to blue. Then, instead of the large, flaming eyes with their fixed gaze, and the long, distended tongue, the new Kālī looked like a normal woman; Pāl gave her realistic eyes, which made the image less formidable, and an average-sized tongue. Whereas in the older images the Goddess stood in a static pose, with the front of her body facing directly ahead and standing on Śiva, lying lengthwise underneath her feet, Pāl tilted the image forty-five degrees to the right, such that the entirety of Śiva’s body was visible. Kālī does not just stand on him; she walks over him, as if heading off to the right, but turns her body to face the viewer (fig. 6.4).40

Newspaper reporters in 1934, 1935, and 1936, when Pāl’s innovation was still very new and called for commentary, described his image as “a brilliant combination of the artist’s versatility and inspiration and the modeler’s mastery of craft. It sufficiently demonstrates how the creation of beauty is made practicable if the oriental method of art is vitalized by a sense of reality and an understanding of the rhythm of motion.”41 Again, the “Kali image of Thanthania Sarbajanin offers a new aesthetic interpretation on a time-worn superstructure. A thing of beauty is a joy forever and when religion is joined to beauty, the delight is all the more brightened. No wonder therefore that the city of Calcutta jostled their [sic] way to the College Row to pay their tribute of homage and reverence to the Magna Mater.”42

FIGURE 6.4. N. C. Pāl’s new Kālī of the 1930s. Amrita Bazar Patrika, 2 Nov. 1937, p. 6.

From my perspective, the most interesting remarks on the new Kālī are those that relate her beautified appearance directly to the Tantric dhyānas. In a 1936 article by Ashokanath Shastri, the older images are critiqued for their departure from the spirit of the dhyānas, since their stiff postures and stylized faces fail to capture the spirit of motion and energy communicated in the Tantric descriptions, where “the whole atmosphere is surcharged with the mingled expression of fierceness, divine beauty, and sacredness.” He ends by referring to N. C. Pāl’s sweetened image at Thanthania as a true example of the mood and intent of the dhyānas.43 For this author, then, the move to increased realism is also a fulfillment of the Tantras.

Eventually called the “Orientalist,” “Artistic,” or “Modern” (Ādhunika) school, as opposed to the “Bengali” (Bāṅglā) or “Ancient” (Puraṇa) school, the conventions initiated by N. C. Pāl were instantly popular, and have remained so up until this day. Pāl’s sons and grandsons have continued the tradition at Thanthania, which is still one of the premier attractions in the city at Kālī Pūjā time. If one follows the Calcutta newspapers from 1934 up to the present, with an eye to which type of images are photographed and published, one finds that for many years in a row it was only the new, Orientalist type that was noted and commented upon by the staff reporters.44 It is not until 1963 that I find a single published photograph of the older, fiercer type of Kālī—and this was offset by another, humanized Kālī on the same page.45

More recently, along with the resurgence of interest in old Bengali songs, the traditional Kālīs, who never lost their popularity among established families sponsoring Kālī Pūjā in their homes, have made a comeback in the sarbajanīn contexts as well; over a three-year period, 1998–2000, Abhijit Ghosh did a survey of one hundred Kālī images each year in the same Pūjā pandals of southern Kolkata, taking note of various iconic cues: face design (fierce or sweet?), color (black, light blue, gray?), torso depiction (static, in motion?), the position of Śiva relative to the Goddess (lying parallel or perpendicular?), and so on. He found that fully one third of the Kālīs in all three years represented the fierce, old-style tradition.46 As one Bengali writer phrased it in 1993, “of all the images made according to custom, the ones from the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries are the most important.”47

Which Face Do You Want? The Modern Inheritance

Which kind of Kālī, indeed, is the more important? Why, and to whom? Certainly the blue, sweet, realistic Kālīs are in greater demand and generate more money on the open market. This is not only because they appeal to the heart, reminding one of the loveliness of one’s mother,48 or because they conform more to the vision of the buxom, near-naked woman promulgated by Hindi films—although these are probably influential connotations. Indeed, the explosion of the modern media—portrayals of film actresses and the use of goddesses in advertising—has affected popular ideas of how the Goddess should look. As Satish Bahadur observed sagely in the mid-1970s,

Popular art in any society serves the functions of myth creation and social catharsis. In India, the film is the primary vehicle for the spread of popular culture; the other media tend to model themselves after the style of the film…. Even the traditional iconography of statues and pictures for religious worship has accepted the visual values of the film; the conventional Durga image for the Bengali puja festival is looking more and more like Suchitra Sen!49

In 1995 film star Hema Malini came to Calcutta at Kālī Pūjā time and expressed her hope one day to play Mā Kālī in a film. In the same year, the leaders of the Thanthania Pūjā invited Madhu, “proudly proclaim[ing] how they have been leading the competition in the city to rope in silver screen idols to inaugurate their puja.”50 Idols and idols. Both beautiful.

The newer Kālīs are also, it must be noted, less expensive to make and therefore to buy. Pārtha Pāl and Pradīp Pāl, Kumartuli artisans from different families whom I interviewed in October of 1995, both stated without hesitation that they make more of the modern type of Kālī, and that their numbers are increasing every year.51 These softer Kālīs also sell postcards and inspire calendar art, nine tenths of which depict the newer Kālīs. Comments Kajri Jain, a scholar of Indian mass culture, Kālī in her more terrifying aspects has gradually receded from depiction in calendar art, and is being replaced by a sensuous treatment that can “sometimes verge on soft-focus eroticism.”52

The artisans themselves prefer the older style. According to Pradīp Pāl, they are more “godly” (Bhagavāner mata) and more demure, with their attractive decorations covering the entire front of the Goddess’s body. It is only the modern Kālīs whose upper torso, including her breasts, are regularly exposed (fig. 6.5). The modern goddesses, catering to whim and the vagaries of innovation, also appear more outlandish to the pious. Should Kālī be dressed as Mother Teresa, with a blue-bordered white sari, as occurred in 1997, or as Hanumān, her skin replaced with the furry black hair of a monkey, as found in 2004?53

There are a number of transitional varieties, the most popular being the traditional body (Kālī standing on Śiva lengthwise, her torso lavishly decorated) with the new, smiling, humanized, blue or gray face. This type of intermediate Kālī is at least as old as 1970, where I found it in a newspaper photograph,54 but from the mid- to late 1990s it has become quite the fashion for people who want to maintain something of the older feel without losing the more attractive face. As an indication of its importance, both Pārtha Pāl and Pradīp Pāl informed me that when people want to found a permanent Kālī temple, they most often commission an image with a traditional body and a modern face. Perhaps it is not appropriate to worship, year round, a naked Kālī; indeed, even the permanent Kālī images that are decades or even centuries old are all so draped in saris, flower garlands, and adornments that their bodies are lost to sight. The attempts of the priests in these Kālī temples to emphasize the Goddess’s decency and sanctity (or to preserve those of her viewers) are enhanced by her ornaments, signs of a married woman: bangles, earrings, and red powder on the hair parting.

FIGURE 6.5. A modern Kālī, with Śiva nearly sitting up. Kolkata, October 1998. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

Let me return to the comment made in 1936 by Ashokanath Shastri, on the relation between these new images and the Tantric dhyānas. Is it true that N. C. Pāl and his followers have brought us closer to the spirit of the Tantras? Has Kālī’s popularization enriched the appreciation of her Sanskrit, ritual past? A comparison between the iconographic prescriptions of the Tantras and the “Artistic” Pūjā images of today yields interesting results. Certainly, the nakedness (from the waist up) of the modern Kālīs, which enables one to get a clear view of the skirt of cut arms and her muṇḍamālā, is more in keeping with what the dhyānas designate. Furthermore, most artists add jackals poised hungrily underneath the dripping head in her hand, and even, occasionally, yoginī companions—all part of the Tantric description. Kālī’s alluring smile can also be said to derive from the dhyānas, which praise her face for its beauty.

On the other hand, the traditional Kālīs outdo their newer counterparts in their faces. Through their large eyes outlined in red, barred teeth, and longer tongue, they preserve the spirit of what nearly all the dhyānas state about this deity—that she is ghorā (horrible) and has a frightening face (karālavadanā). Also, although the realistic portrayal of motion and activity in the modern Kālīs undoubtedly brings the scene alive in a way that the older images do not, it is questionable whether the Tantric sādhaka, sitting alone meditating on the Goddess in his heart, was endeavoring to watch a simulated battle, complete with movement. What modern craftsmen have done is to turn an icon meant for contemplation into an imitation of life.

But there are aspects of Kālī as depicted in the dhyānas that neither old nor new Kālīs display at Pūjā time. Where, for instance, is the depiction of her open-mouthed horrid laughter (aṭṭahāsa), her drunkenness, her corpse earrings, or the blood dripping from the corners of her mouth and from the recently cut necks of her necklace onto her breasts and torso? Most especially, why is she standing and not seated on Śiva? And why is there no hint of the viparīta rati, or reversed sexual intercourse, which the two are enjoying? What does one make of the fact that most of these missing items are prescribed in Kālī’s most famous dhyāna from the Kālī Tantra, which is printed in all of her ritual manuals (pūjā paddhatis)?

Although there are a few old-style images that do retain some of these more forbidding elements,55 they are obviously a minor tradition, and both old and new Pūjā images appear to leave out significant details of Kālī’s Tantric demeanor. It is my contention, however, that the new ones leave out more. For what seems quite far from the vision of the Tantric dhyānas is not so much the lack of iconographic details—in some senses the more realistic, modern goddesses include more of these—but the intent behind those details; there is very little that frightens in most modern renditions. Kālī’s beautiful face and shapely, graceful body make her bloody accoutrements seem incidental or even comic by comparison. In this same vein, the position of Śiva, relative to that of the Goddess, has now been transformed even more radically than what was conceived under N. C. Pāl: Kālī sometimes stands atop her Lord, legs akimbo, so that the two are completely perpendicular to one another; and sometimes he nearly sits up, his head resting on his hand, to watch her (fig. 6.5). The overall inherited form of Kālī is still more or less present, therefore, but the implied meaning appears to have changed. Of the nine dhyānas surveyed for this chapter, the realistic Kālīs of the Kumartuli workshops conform most closely to that of the Bṛhaddharma Purāṇa, which contains little blood and gore and includes plenty of references to her smiling face and shapely breasts. The Purāṇic, nonsexual Kālī, once overshadowed by her Tantric counterpart, has regained market share.

The Kumartuli artisans admit their departure from the Tantric models. Pārtha Pāl told me that he had never seen a Pūjā image with blood dribbling out of Kālī’s open mouth or with corpses dangling at her ears. “That’s too dreadful (bhayaṅkara),” he told me. His older colleague, Pradīp Pāl, later agreed: “If we follow the Śāstric injunctions, no one will buy our images.” Professor Nṛsimhaprasād Bhāḍuri, a specialist on Śāktism, had perhaps the most intriguing comments to make about Kālī’s new form. The traditional Kālī, standing lengthwise over Śiva, is closer to the purport of the dhyānas, since it is possible to conceive of engaging in amorous activity from that position. In other words, while not actually depicted, viparīta rati is suggested. But this suggestion is masked when Kālī is turned to the right, as in the modern versions. Bhāḍuri claimed that this was the conscious decision of the artisans, who, with a “gentle touch” (bhadrāyana), altered the image for the sake of humanization (mānabāyana) and—I might add—propriety.56

Looking over Kālī’s iconographic history as a whole, it appears that certain aspects of the Tantric meditational prescriptions have always been overlooked in the externalization of her image: hints of sexuality, her peculiar earrings, her drunken bellowing, and the glistening blood on her body. With N. C. Pāl’s innovation and the attempt to create more realistic images, some parts of the dhyānas not often depicted in the older Kālīs—such as her nakedness and smile—were retrieved. As a result, the frightening effect of the fierce-faced Kālī with the bloodshot eyes and thirsty, extended tongue was attenuated. Sweetness and humanization are now preferred to the static icon of awe.

But must one choose? Pradīp Pāl informed me that, although it is rarely commissioned, there is a form of Kālī that holds together the suppleness of the new Kālī body and the “godly” look of the old Kālī face. Apparently, Belur Mah, the monastic headquarters of the Rāmakṛṣṇa Mission, requests this every year. Not everyone wants to see a movie star or one’s mother in the Goddess’s face.

Gains and Losses in the Travels of an Icon

Now when I visit Kumartuli and pass by an artisan’s godown, where Kālīs-in-waiting are drying or having their bodies painted and bedecked, I see a lot more than I did in 1989. Especially when the studio is home to old and new styles of image, standing next to one another, Kālī’s processional history seems to stand in front of me. I am reminded of the glossy pictures produced by the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, in which the stages of a man’s life are depicted by several images in succession: first the baby, then the adolescent, then the mature adult, and then the wrinkled man bent over his stick. At Kumartuli we do not see either the Kālī of the Tantric dhyānas, meant to be visualized inside the adept’s heart, or the Goddess as her seventeenth- to eighteenth-century sculptors first externalized her for temple worship, though the Bāṅglā or Puraṇa Kālī, with her formidable, fearsome mien, is a close approximation. It is the blue Kālī—looking younger and younger under the craftsmanship of N. C. Pāl’s inheritors—who is furthest away from her Tantric birth. And it is she who epitomizes and embodies the average devotee’s disquiet over the bloody, sexualized, power-conferring properties of Tantric ritual.

However, there continue to be people for whom the worship of Kālī is not genuine if the Tantric elements are omitted. One wonders what Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902), who died before the innovations of the 1930s, would say about this avoidance of Kālī’s dread nature. For while alive he castigated in biting language those who smoothed away her awesome side:57

Lo! how all are scared by the Terrific,

None seek Elokeshi whose form is Death.

The deadly frightful sword, reeking with blood,

They take from Her hand, and put a lute instead! …

True, they garland thee with skulls, but shrink back

In fright and call Thee, “O All-merciful!”

But Vivekānanda’s is a minority voice. As I have tried to demonstrate in this chapter, Kālī’s emergence into the popular world, with its consequent humanization and animation, was encouraged by many, in different decades and walks of life, who benefited from making her symbolism, might, and allure more accessible. For some the publicizing of her Tantric ritual in digests and manuals represented a means of countering, or subsuming, the threat of Vaiṣṇava popularity. For others, the patronage of her vernacular literature, her temples, and her annual festival offered legitimation for social and political ambition. Still others, fighting British imperialism, either emphasized her puissance in the name of political subversion, quoting Tantric ritual mantras to justify killing in her name,58 or folded her into a generic symbol of Motherland, to be cherished and protected. In the more recent past, in response to public taste and the exigencies of economic demand, her artisans have softened her yet more, creating with their “gentle touch” a Goddess who not only acts but also looks like one’s beautiful mother. In other words, Kālī’s path—remarkably similar to that traveled by Durgā and Jagaddhātrī, as we have seen in chapter 4—is the outcome of the intersection between historical, social, and political circumstance, and the active choices of her Bengali mediators.

But the end result has been the transformation of an icon, an image that—like those in the Eastern Orthodox churches of Byzantium and Russia—was meant for installation in the heart, an adoring inner gaze, and not the reproduction of reality. Through their frontal depictions, immobile bodies, often distorted facial proportions, and dignified colors, icons evoke feeling, express metaphysical profundity, and encourage absorption. The Jesus of the icons, to continue with the Christian parallel, is not the “friend” of modern Protestant posters, for there is nothing sentimental about iconic portraits, which guard against overfamiliarity with the divine. The same can be said for the older Kālī, who, with her stationary stance, exaggerated eyes with their fixed stare, severe visage, and bold colors of red, white, and black, invites a return gaze, a contemplative touching of eye and heart. But Russian icon painters of the late seventeenth century, influenced by Western Renaissance reforms, began to value naturalism, perspective, beauty, gentleness, and motion, which detracted eventually from the intense, spiritual effect of their former art. The same has happened in the modern Bengali milieu. Kālī is pretty, pleasing to behold, but to many Bengali devotees she is in danger of losing her “godly” side.

It is ironic indeed that in spite of their being claimed to communicate best the specifics of the dhyānas, the newest Kālīs conceal as much as they reveal about her Tantric origins. How many Bengalis know, or admit to knowing, that the primary reason Kālī stands on Śiva is not because she mistakenly stepped on him but because she is about to sit for conjugal bliss?59 Or what about the outstretched tongue, which in the newer images is so short that it lends credence to the popular story of Kālī sticking it out in embarrassment, rather than extending it thirstily for blood? Finally, many a blue Kālī has a red lotus painted around her mouth; what is this but a creative maneuver to mask her blood-smeared lips? In sum, while her artisans may have altered Kālī’s stance, literally and figuratively, to reflect changes in public taste, at least one of her feet remains firmly planted on Tantric ground—and this in a manner befitting Tantric esotericism, whether her votaries acknowledge and approve of it or not.