7Approaches to Kālī Pūjā in Bengal

This chapter1 continues our focus on Kālī but moves from an emphasis on iconography to a discussion of the festival proper—chapters 6 and 7, then, mirror chapters 4 and 5, which covered the same two large topics, for Durgā and, to a lesser extent, Jagaddhātrī. Kālī’s festival follows Durgā’s by three weeks, on the dark-moon night of the month of Kārtik, coincidentally also Diwali.2 In many ways their pairing makes sense, as from at least the sixth century C.E., Kālī has been claimed as a multiform of Durgā who issued like a daughter, younger sister, or helper from Durgā’s angry forehead to help her battle demons.

Not surprisingly, the two Pūjās have developed in tandem: as we have seen in chapter 2, Kālī, like Durgā, was utilized in the expression of anticolonial and communal political rhetoric; chapter 5’s discussion about Durgā’s debut from elite origins and her evolution through to the public, popular form of her festival is equally true for Kālī, even up to the modern craze for the “Theme Pūjā”3; and chapters 4 and 6 illustrate how the iconographic depictions of both goddesses have changed in the direction of softer, more humanized portrayals. The two festivals are even linked in the artisans’ studios, for Durgā faces salvaged from the river after immersions are turned into the ḍākinī and yoginī figures that accompany Kālī at the next Pūjā. Notwithstanding these significant areas of overlap, there are also important differences between the two festivals, and these will concern us for the remainder of the chapter.

Not Twins: Different Births, Different Lives

Kālī’s Spotlight Is Smaller

Even the staunchest devotee of Kālī must admit that her pedigree cannot match Durgā’s. While we have evidence for the performance of Durgā Pūjā as far back as the sixteenth century, and perhaps even earlier, we cannot date Kālī Pūjā much before the mid-eighteenth century. The most well known story of its rise in Bengal concerns Rājā Kṛṣṇacandra Rāy, Nadia zamindar and Śākta patron of the mid-eighteenth century. William Ward, writing in the second decade of the nineteenth century, states that Kṛṣṇacandra ordered all his subjects to perform Kālī Pūjā on pain of penalty; apparently more than ten thousand people in the Krishnanagar area complied. Kṛṣṇacandra’s grandson, Īśāncandra (who would presumably have been alive during Ward’s day), also patronized Kālī Pūjā on a grand scale, offering eighty thousand pounds of sweets, one thousand goats, sheep, and buffalos, and one thousand saris to the Goddess. Finally, Ward notes that Rājā Rāmakṛṣṇa Rāy of Natore expended one lakh rupees on a Kālī Pūjā image.4

There are indications that Ward’s claim for the late date may be correct. Many of the sixteenth-century ballads from eastern Bengal retrieved by Dīneshchandra Sen contain bāromāsī (“twelve month”) sections, with stylized descriptions of what festivals occur each month of the year; while Durgā Pūjā is almost always referred to in September/October, Kālī Pūjā is rarely included for October/November. Again, mentions of Kālī Pūjā are completely missing from Tantric texts that are otherwise devoted to the specifics of her worship.5 Chintaharan Chakravarti suggests Kāśīnāth’s Śyāmāsaparyāvidhi of 1777 as the oldest reference to Kālī Pūjā, since Kāśīnāth quotes Tantric passages in a manner calculated to prove Kālī’s importance.6

Moreover, of the two, Durgā Pūjā has always been the more popular and has always received more news coverage, in both English and Bengali; indeed, Kālī Pūjā is virtually absent from the papers into the early twentieth century. When there is a story it focuses on Diwali, and mentions street illuminations, firecrackers, foods, new account books, Lakṣmī, day trips for Europeans, and gambling. Kālī does not appear at all, except in the context of the Kālīghāṭ Temple, where people go on Diwali for sacrifice and the starting of the new year.7 Published interest in Kālī Pūjā per se begins to grow slowly, and only from the late 1920s with the new sarbajanīn festivals, and the 1930s with the new humanized goddess depictions. Diwali always tops the Pūjā in terms of photos and news coverage, however, and this remains true into the 1980s. Striking as an example of the imbalance of attention to Kālī vis-à-vis Durgā is the Pūjā season coverage for 1964 of the Bengali newspaper Ānanda Bājār Patrikā: there are three photos, total, of Kālī images, compared with 143 of Durgā.8

Kālī Pūjā pandals also tend to be smaller, less often thematically decorated, and less gorgeous than Durgā’s counterparts,9 although, interestingly, since the mid-1970s Kālī Pūjā pandals have totaled more than twice the number of Durgā Pūjā pandals. The reason for this, explained Subhas Ray, personal assistant to the deputy commissioner of police at Lal Bazaar, is that Durgā Pūjā pandals are larger, are more expensive, cause more traffic congestion, and hence are more strictly regulated.10 Kālī, I have also been told, does not need splendid temporary shrines in which to take residence, as Bengal is dotted with thousands of Kālī temples, which become the nexus of activity at the Pūjās. This is not true for Durgā, however, who, due to some peculiarity of fate in Bengal, has almost no permanent temples.

Her Reputation Is More Formidable

A second major difference between Durgā and Kālī Pūjās is Kālī’s association with fear and power. Rarely identified with the girl or daughter of the house, as is Durgā,11 Kālī’s iconography is more forbidding, and she is more prone to punish for ritual infractions. Even twenty-five years after the sarbajanīn Pūjā format had become popular, certain people were still hesitant to take it on. Stated Śākta expert Narendra Nath Bhattacharyya when commenting about his college days in the late 1950s, “Kālī bāroiyāri was rare, because one was afraid.”12 In an article for the Statesman’s Puja supplement for 1957, Tapanmohan Chatterji writes that Kālī’s tongue is out “for a taste of the warm blood of her victims” and that people worship her out of fear of her curses.13 Sudhīr Kumār Cakrabartī, writing a Bengali article specifically aimed at explaining the various aspects of Kālī, omits discussion of the three eyes, bloody tongue, and cremation-ground dwelling, “for fear.”14 This sense that Kālī’s power is not to be disregarded is exemplified in a news story from 2003 about a father who dreamed that if he did not marry off his two minor sons immediately, the Goddess would kill them.15

As we saw in chapter 2, Kālī’s fearsome demeanor and connoted potency were particularly efficacious in galvanizing public support for nationalist causes. During the early 1920s, an author writing for the Ānanda Bājār Patrikā during Kālī Pūjā season used her cremation-ground imagery to challenge Bengalis to act: “Are the great bhairavas awake, those who will sit doing śakti-sādhanā on the corpses of this race? Are the priests of the new era ready, those who have prepared the offerings for the worship of the Mother who dwells on the great charnel grounds of Bengal, flooded with skeletons of our past glory? Will they be able to satisfy the Destroyer by their pūjā, offering bestial things such as the fear, shame, dirt, and the unending sorrow of Bengalis? If not, then there is only darkness, and the fear of ghosts…. In order to receive without fear her boons of fearlessness and aid, call on the Mother without fear in the midst of the famine and hardship pervading our country.”16 One of the forms of Kālī, in fact, is specifically called Cremation-Ground Kālī, or Śmaśānakālī, and there are both permanent temple images and sporadic temporary images of this type erected during the Pūjās.17

Kālī is not only potentially frightening herself; she also has strong links to fearful people. Antisocials and goondas, for instance, are frequently central to her temple foundation stories. Indeed, there is a whole genre of Kālī images called Ḍākāt Kālīs, for their association with the robbers or dacoits who founded or patronized them. The town of Shantipur, in Nadia, a Śākta heartland, specializes in Ḍākāt Kālīs.18 Modern-day goondas are often involved in the sponsorship of Kālī Pūjā pandals: “Criminals in Bengal have always been attracted to the rituals associated with Kali Puja. … Community Kali pujas are basically by the goondas, of the goondas, for the goondas.”19 As Nazrul Islam, deputy police commissioner, further explains, rowdies are attracted to Kālī because people are afraid of her and her devotees and hence are more likely to give money to support pandals; because intoxicants are considered her prasād; and because it is widely believed that if you commit a crime on Kālī Pūjā and evade capture, you will be protected the whole year.20 Anyone who has spent any time in West Bengal will have heard stories of harassment and forced subscription payments by local toughs at Kālī Pūjā time, and of rowdy behavior, drunkenness, and gambling.

Corruption or bad behavior exhibited by people responsible for Kālī’s numerous temples also lends her a dubious reputation, by association—something that does not happen with Durgā because of her lack of permanent temples. In Kolkata, the most famous temple is Kālīghāṭ, widely critiqued as a dirty, unkept zone where pilgrims are harassed by greedy ritual specialists. In 2004 the Government of West Bengal announced that it would pay to have the temple renovated, but the Temple Trust did not cooperate, fearing interference in the running of the site, and in 2006 the courts banned the pilgrim guides (pāṇḍas), widely experienced as rapacious, from entering the inner sanctum of the temple. In responding to accusations that the temple authorities were misappropriating devotees’ offerings, the courts also mandated that offerings would have to be dropped into sealed boxes, and that a representative from the district magistrate would have to be present when they were opened. Kālī temple functionaries are not necessarily, it appears, a trustworthy lot.

Another type of person associated with and attracted to Kālī’s worship is the Tāntrika, or practitioner of ritual derived from the Tantras. Almost every Kālī temple of any repute, especially if established in the eighteenth century or earlier, is said to have had a Tāntrika in its history or to have been established by a Tāntrika on a human corpse.21 In Kolkata this is true of Ānandamayīkālī of Nimtala, Siddheśvarīkālī on Citpur Road, Siddheśvarīkālī of Thanthania, Jaykālī of Shyambazar, and even the fairly new Lake Kālī Temple, from 1948; one can find numerous similar stories from all over the state. Moreover, all Bengali towns and cities have their resident Tantric astrologers and siddhi-wielders, men who offer to help you with love, marriage, business, children, education, family troubles, and even enemies. One fervent Kālī devotee, Tāntrika, and Ph.D. student whom I met at the University of Calcutta told me that he could arrange to have anyone who was troubling me killed. The dacoit or lawbreaker and the Tāntrika are sometimes conjoined in Kālī contexts. Two of the biggest Kālī Pūjās today are organized by clubs in Chetla and Kalighat that have rather dubious reputations. They worship the Chinnamastā and Cāmuṇḍā forms of Kālī, complete with blood sacrifices performed by red-robed Tāntrikas.

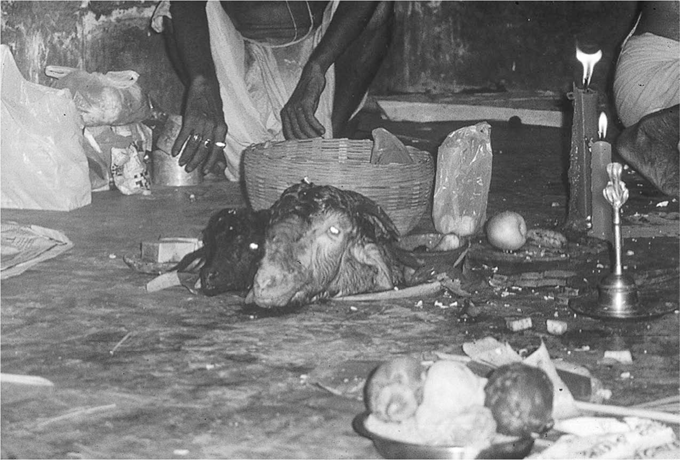

In addition, old families with traditions of worshiping Kālī often do so according to Tantric rites. Belpukur, a village in Nadia district north of Krishnanagar, for example, is famed for its Tantric Kālī Pūjās: animal sacrifice is important (fig. 7.1), alcohol (kāraṇabāri) replaces Ganges water for ritual sanctification, and alcohol is also offered to the deity.22 It goes without saying that iconographically all of these temple and home images are of the old, traditional, fierce variety.

In spite of the fact that Durgā, too, came into prominence through the active patronage of elite families, her history does not include dacoits or Tantric sādhakas. Although Durgā Pūjā is described in Sanskrit and Bengali Tantric texts at least since the tenth century, Durgā’s worship has been linked with royalty and with householders, not with heterodox rituals.23 Nor does she have the same fearful reputation. She is, to be sure, dread-inspiring to Mahiṣa and other demons whom she kills, but her iconography includes a plethora of weapons for war, not heads, severed limbs, or other dismembered trophies of war. Because of her closer mythological ties to Śiva, her identification with the Bengali daughter and daughter-in-law, and her more benign visage, Durgā appears to have been less heavily Tantricized.

In this context, the fact that Kālī Pūjā and Diwali, the pan-Indian festival of lights that celebrates the pacific deities Lakṣmī and Gaṇeśa, occur on the same night results in a rather peculiar conjunction of ideas, rituals, and ideological associations—more so than occur as a result of the parallel conjunction of Bijayā Daśamī with the slaying of Rāvaṇa by Rāma.24 Diwali is a home-based festival, and it communicates auspiciousness, new beginnings, and a sense of well-being—not the awe associated with blood sacrifice and midnight ritual. Wrote Abhī Dās, in “Sekāle Bāṅgālīr Kālīpūjā,” in 1985: the conjunction of Diwali and Kālī Pūjā is ironic, as they are exact opposites. Diwali represents fortune and victory, Lakṣmī’s face is yellow and smiling, and she is worshiped with lamps and white flowers. Kālī, on the other hand, represents famine, war, rebellion, and fear; her face is black and fearsome, and she is worshiped with red flowers and darkness.25 Another Bengali author noted with chagrin how much Kālī Pūjā is being affected, Indianized, and genericized by its conjunction with Diwali.26 Local stories abound as to the reason for the simultaneity of the festivals: Lakṣmī and Kālī came together, as opposites, from the churning of the milk ocean; Kālī needs light to fight demons; and light helps establish the boundary between the living and the dead, since the dead visit the earth at Kālī Pūjā, and one needs to keep the evil spirits at bay.27 Clearly there is a perceived disjunction between the festival cultures that occur on the dark-moon night of the month of Kārtik.

FIGURE 7.1. Goat heads placed before the image of Kālī at a house Pūjā in Belpukur, a village in Nadia district north of Krishnanagar. November 1999. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

She Is Raw, Sexualized, Immodest

In spite of the normative iconographic tradition of Kālī standing upon the chest of her husband Śiva, since the fifteenth century the Tantric dhyānas that describe her meditational form actually indicate that she is supposed to be seated on him, since they are engaged in viparīta rati, or the pleasure of reversed sexual intercourse.28 A few old images and paintings from the nineteenth century mirror this prescription: Śiva’s penis, testicles, and pubic hair are prominently depicted in a late-nineteenth-century Kalighat paṭ in Kolkata’s Asutosh Museum;29 the British Museum houses a fierce black clay Kālī, with red-ringed breasts, children’s corpses adorning her ears, a girdle of hands that fails to cover her pubic area, and an ithyphallic Śiva;30 the same museum retains a large watercolor painting (ca. eighteenth–nineteenth century) depicting a three-cornered yantra, inside of which is a seated light-colored Kālī engaged in intercourse with a three-eyed, ugly, dark blue demon whose erect penis is clearly visible (they are seated on Śiva, who is seated on a corpse);31 in Krishnanagar at the Ānandamayī Kālī Temple, Kālī sits on Śiva, who is acting as her Tantric meditation seat (fig. 7.2);32 and in Hooghly district one can visit the home of Abadhūt, a Tantric sādhaka from the early twentieth century who painted a picture of Kālī nude from the waist up, seated in intercourse with Śiva, blood trickling from her open mouth onto her exposed breasts.33

FIGURE 7.2. Kālī seated on Śiva, Ānandamayī Temple. Krishnanagar, October 1998. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

Seeing all these images reminds one that this goddess derives from an esoteric, Tantric world that is neatly disguised by today’s pretty Pūjā images, where Śiva is either asleep, amused, or focused on something else. The sexual element is not however completely missing, even if intercourse is not indicated, for many of the post-1926 images of Kālī (but not Durgā) leave the breasts uncovered. Some contemporary Bengali women find this immodesty unbecoming and embarrassing; Kālī’s sexuality is uncomfortable.34 When I was in Kolkata in 2000, a local controversy raged over a seventy-five-year-old Tantric priest who for the prior fifty years had been worshiping a series of ten-year-old girls over a wooden pyre in the Kasi Mitra Burning Ghat in northern Kolkata on Kālī Pūjā night. The Tāntrika removed all his clothes for the event, and he and his assistants went into trances, cut themselves with knives, collected their blood, and offered it to the Goddess. He then washed the little girl’s feet with alcohol and licked them clean. Neither the police nor the health department nor the current little girl’s mother was happy about the practice, but, citing “tradition,” they were all reluctant to stop it.35 Tantra, sexuality, blood, and fear: these are unavoidable aspects of Kālī’s inheritance.

Durgā’s persona is not nearly as sexualized as this; in one Oriya version of the Mahiṣa myth, she is said to be enraged that Mahiṣa is granted a boon of being able to be killed only if she shows him her privates,36 but such is never depicted or exhorted for meditation in Bengal, and sexual rites are not a part of her worship. There is an aspect to Kālī Pūjā that is, or has the potential to be, both more fearful and more immoderate than anything one finds in its more popular sister festival.

Differently Empowered: Comparative Conceptions of Śakti

The various contrasts we have been enumerating can perhaps best be summed up by recourse to notions of śakti. I asked several scions of the old families who still carry on the tradition of celebrating Durgā Pūjā and/or Kālī Pūjā how they would compare the two goddesses. Two themes predominated in their comparative responses. First, they said, Durgā is either the daughter of the house (bāḍīr meye) or the universal mother (sabāier mā), whereas Kālī is a symbol of power (śaktir pratīk), whose wrath, in case of a ritual mistake, is a cause for fear (bhay).37 Second, Durgā fights for us in battle, as would a mother, whereas Kālī is angry (or has rāg) in general, and could turn against us with her uplifted khaḍga.38 Keeping these contrasts in mind, it is easy to see why some interviewees asserted that “Kālī is only for Śāktas; Durgā is for everyone.”39

Although one would not want to draw these distinctions too tautly, especially given the bhakti perspective on Kālī, one might characterize Durgā’s power as protective, maternal, and distributive, and Kālī’s as contractual, won by or offered to the deserving, and associated with aggrandizement and personal power. As a result, it is easy to understand how Kālī became associated with revolutionaries’ power quests, whether during the colonial period or during the 1970s reign of terror by the Naxalites, for whom, “like the red flag of the Communists, Kālī is a symbol of revolution.”40 Even today, the trail to the Kālīghāṭ Temple of aspirants to would-be regal power continues this connection between Kālī and political śakti; for instance, in 2002, erstwhile King Gyanendra of Nepal, following the custom begun by his father and brother, came all the way to Kālīghāṭ from Kathmandu to offer two goats and several gold pieces to the Goddess.

Held Back, Pulled Forward: Analyzing Kālī’s Pūjā

Given Kālī’s Tantric origins, it is perhaps not surprising that her persona maintains something of its esoteric, fearsome, sexualized character. While it is true that since the eighteenth century Kālī has been softened and maternalized by her incorporation into a bhakti tradition, the preceding layers of her history—her bloodlust for demons, her utilization by Tāntrikas in meditation for the acquisition of siddhis, and her reputation for wrath—have been neither superceded nor entirely hidden. And one would not expect them to be, for a goddess’s past, and a community’s past, are defining for their present. As Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann stated in their landmark study, The Social Construction of Reality, remembering the past is very significant in the socialization of individuals and contributes decisively to the formation of their identities.41 Even if they are somewhat afraid of the Goddess, Śāktas who consider themselves Kālī-devotees value her historical associations with siddhis, power, and particular sādhakas such as Rāmakṛṣṇa and Rāmprasād. These are part of a “pastness” that contributes to her authenticity and that creates a context for popular memory and nostalgia.

This estimation of her heritage becomes all the more important when one considers that Kālī Pūjā is not in fact old at all, since, as indicated earlier, we have no evidence that it predates the eighteenth century. In the language of Eric Hobsbawm, what Rājā Kṛṣṇacandra Rāy of Nadia and his contemporaries did for Kālī Pūjā was to create an “invented tradition,” establishing within a fairly brief period a public celebration that was legitimized by the simultaneous sponsorship of newly translated Tantras and the construction of goddess temples.42 Not only was Kṛṣṇacandra thus encompassing his newly ritualized Pūjā within supporting structures; he was also following the injunctions of the Goddess herself, to whom the maintenance of her “traditions” is said to be extremely important. Thus the zamindars’ innovations were presented as continuous with a valued past. The same impulse to legitimize by reference to antiquity can be seen in the admiring reactions of journalists to the innovations of the 1920s; they were careful to point out that the sarbajanīn festival format was no more boisterous or ostentatious than were the celebrations of the monied classes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. And one art critic defended the new realism of the N. C. Pāl school as conforming more accurately to the spirit of the medieval dhyānas than did the traditional Bāṅglā style. In other words, newness is acceptable only as a more authentic return to or recapitulation of an esteemed perceived past model. One can perhaps understand the modest revival of the traditional, fierce Kālī images in many contemporary Bengali pandals as an effort to reclaim the power of, as well as even to market, that past.

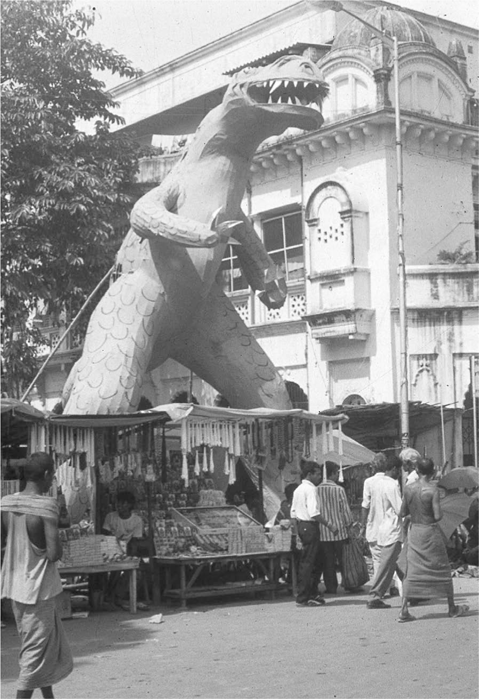

If this heritage that differentiates Kālī from Durgā is thus so important, what accounts for the near parallelism between the two goddess festivals? How can we understand the pull, the draw, of the Durgā pattern for Kālī? Here I find three models helpful. The first is the work of Milton Singer, who was a pioneer in theorizing the effect of urbanization on traditional religion.43 Drawing upon his work in what was then Madras, he showed that the cultivation of bhakti allowed for the relaxation of strict ritual rules, allowing devotees to adapt to situations where traditional practice was either impossible or undesirable. In our Bengali context, the influence of bhakti upon the cult of Kālī over the last two hundred and fifty years has meant that, for some, Kālī the mother pushes aside Kālī the Tantric power, and hence that her softened features can be celebrated without fear and in novel ways, including in an effervescent public festival (fig. 7.3).

A second model derives from the work of Gananath Obeyesekere, who, in his work on the Sri Lankan Buddhist goddess Pattini, describes what happens to the personality of a deity when she becomes more universally popular and hence must appeal to a wider audience: her rough edges are smoothed over, and her purity and benevolence are emphasized.44 To the extent that the Bengali Kālī is, in some quarters, becoming less interested in blood sacrifice and is looking more like a shapely sixteen-year-old or a young version of one’s mother than a skeletal hag, she is following the rubric suggested by Obeyesekere. The greater a deity’s claim to devotee numbers, the more accommodative she must become to their varied tastes.

The final lens through which to view the emergent parallels between Durgā and Kālī Pūjās since the 1920s is that of the leveling effects of middle-class urban religion. To turn again to the work of Joanne Waghorne, who has written about what she calls this middle-class “sensibility,” she argues that all public rituals have been transformed by new contemporary idioms of public culture, where public festivals, of whatever religion,45 take on characteristics of political rallies, movie theater enactments, and mass media entertainment. The middle-class urge to compete in the display of wealth and status, as well as its desire for respectability and its tendency toward gentrification, find expression in temple building and renovation, festival patronage, and the founding of charitable institutions. Writes Waghorne about Mariyamman’s new popularization in Chennai: “As willing as the middle classes are to appropriate the power of the goddess, they do this by cleaning her house and purifying or isolating her coarser elements.”46 From this perspective, Kālī’s Pūjā looks increasingly like Durgā’s because both share in a common urban style of Hindu public religiosity, a globalized local form. Although this is a story for another day, this common idiom is now affecting other deities in Bengal as well, such as Śītalā, Viśvakarmā, and even Lakṣmī.47

FIGURE 7.3. A Jurassic Park dinosaur entertaining onlookers at Kālī Pūjā. Kolkata, October 1998. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

So which is it? Does Kālī Pūjā contain reminders of her fierce past that provide devotees cause for pride—and discomfort—regarding her Tantric origins and distinctiveness? I have certainly argued for this. Or is Kālī Pūjā so much like Durgā Pūjā that both have become examples of a form of urban religion characterized by revelry, rivalry, and even nostalgic longing that has developed fairly uniformly since the 1920s? I have provided evidence for this point as well.

In the end I am forced to conclude—like Kālī herself, holding Tantric reminders in one set of hands and devotional reassurances in the other—that both interpretations are true. One cannot judge as anything other than a desire to control and enhance the experience of Kālī Pūjā, the spate of police-initiated directives forbidding rowdy-ism, dangerous firecrackers, noise level above a certain decibel, and Kālī images too tall to pass under electric wires on their way to river immersions. The 2004 announcement that Kālīghāṭ and Dakṣiṇeśvar were being scheduled by the Government of West Bengal for massive renovations—to be directed by the Kolkata Municipal Development Authority, overseen by the State Tourism Department, and paid for by a Boston-based NRI group called the Boston Pledge—was welcomed by most pilgrims, since the plans included guesthouses of international standards and even carparks.48 Such a move was intended to commodify, market, and upgrade the Goddess. That, as of 2009, the temple renovations were still blocked by the temple authorities themselves shows that not everyone values the middle-class ideals of cleanliness, order, and public accountability.

FIGURE 7.4. The Kālī too horrible to worship. Bartamān, 27 Oct. 1995, p. 3.

Other reminders of the older, fiercer, less controlled Kālī also lurk underneath the surface. In Kālī Pūjā 1995, the Bengali newspaper Bartamān ran a story about a sarbajanīn image of a Cāmuṇḍā-esque Kālī, copied from a real image supposedly found in a cave in Himachal Pradesh and set up in a Kolkata pandal. It was so ugly and horrifying that no Bengali Brahman priest was willing to perform her pūjā (fig. 7.4).49 Two Tāntrikas appeared and informed the pandal organizers that if one wanted to worship this type of image, human sacrifice would be necessary. At the conclusion of the Pūjā, it was immersed without ever having had the Goddess’s life invited to vivify it. Thus even an expansive bhakti perspective and an inviting street-festival context were powerless to transform the ugliness and dread of such an image.

It is not surprising that in the worship of a deity there are limits to how much the past can be watered down or smoothed over. One would not expect Kālī to become dissociated from her moorings and transmuted into a copy of Durgā, for the two goddesses are quite distinct—textually, philosophically, and in the context of private devotion and ritual. And yet the fact that, even if only on the surface, Kālī’s festival has become so like Durgā’s, with its sexy goddess images, its jocular, competitive, public nature, and its incorporation into a yearly round of familiar rituals for the divine Mother, testifies to the democratizing and leveling effects of bhakti, popularity, and urban religion. The street festival forms it own homogenizing world.