GIS and small-area estimation of income, well-being and happiness |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

■ Combining small-area data with national social surveys to estimate small-area information

■ Identifying and studying interdependencies between variables at the local level

■ Becoming familiar with statistical modelling approaches to the analysis of small-area data

■ Becoming familiar with geosimulation and spatial microsimulation

■ Estimating small-area information on ‘soft’ variables such as happiness and well-being

■ Becoming familiar with a wide body of literature on small-area estimation

In this chapter we provide an overview of GIS-related methodological tools that can be used to combine different sets of secondary data in the social sciences in order to estimate small-area information on very important policy-relevant variables that are not typically available from publicly available data sources. Examples of such variables range from household income and individual earnings (which are typically collected by governments and tax authorities, but which are often deemed to be politically and socially sensitive and are not made publicly available due to confidentiality concerns) to variables that are often not routinely available such as health and health-related information, subjective well-being and happiness. The estimation and mapping of small-area distribution of these types of variables at small-area levels has always been a very challenging exercise, but there has been a rapidly increasing number of projects that utilise GIS-related methods to build relevant geographical databases.

The best source of small-area socio-economic information in most countries is the census of population. However, in many cases the census does not provide any information on variables such as household income, wealth and taxation in order to preserve confidentiality (Marsh, 1993) and to minimise non-response even though collecting information on income would be extremely useful for policy analysis. Aspects of such information are available from various government surveys but in many cases the finest spatial scale to which these survey data are coded is the region or, in the case of surveys such as Understanding Society (formerly known as the British Household Panel Survey [BHPS]), in the UK, the local authority district. Even then such sample surveys provide incomplete geographical coverage. Despite these problems and issues, there has been considerable progress (especially over the past 20 years) in the development of small-area microdata estimation methods.

Even in the cases where small-area information on income and economic circumstances is available, there is typically a lack of additional detail in the form of small-area microdata (e.g. a list of individuals with estimated income, employment status, number of children, educational attainment, etc.) that would enable the study of interdependencies of variables at the small-area level (e.g. poverty and educational attainment or educational opportunities, or estimating the number of children living below the poverty threshold in families with unemployed parents).

This chapter (and accompanying practical) provides examples of how it is possible to combine national social survey data with geographical data in order to address the paucity of microdata at small-area level. In addition, it shows how these methods can be used in a GIS context for what-if policy analysis. We begin by providing examples of national survey data that can be combined with the types of data reviewed and discussed in previous chapters (including some of the small-area data sources presented in Chapter 2). We then discuss relatively simple methods of estimating income at the small-area level (e.g. by combining social class and income from a survey with small-area data on social class), before moving on to more sophisticated modelling methods. Finally, we provide applied examples and outputs of such methods and discuss their policy relevance and societal importance. These examples include the geographical analysis of national social and area-based policies, involving the investigation of the geographical implications of national policies, current trends in socio-economic polarisation and inequalities between and within cities.

Overall, the data and methods presented in this chapter demonstrate the huge potential for GIS to be used to estimate very important small-area information and to also address a series of important policy questions from a geographical perspective. However, as the reader will see, we also need to introduce techniques used in parallel with GIS – modelling techniques such as regression and spatial microsimulation. The GIS remains the container for the data and the core software for data visualisation, but greater analytical power comes from coupling other modelling techniques.

Combining small-area with national social survey data

As we noted in Chapter 2, there is a wealth of geographical data ranging from regional to small-area level that can be stored, analysed and visualised with the use of GIS. As argued in Chapter 2, one of the most important and reliable sources of small-area socio-economic data is the census of population, as it is the most authoritative and spatially comprehensive social survey and is used by governments around the world to support decisions pertaining to the allocation of public expenditure at different geographical levels. In addition, census data are very valuable commercially, as they form the basis for geodemographic analysis (as also discussed in the previous chapter) and are used in marketing analysis and retail modelling (see Chapter 8). However, the census data variables are relatively limited on cost grounds and in order to preserve confidentiality. For instance, the questionnaire of the last census of the UK population had 56 questions pertaining to themes such as work, health, national identity, passports held, ethnic background, education, second homes, language, religion and marital status.1 However, it did not include any questions on household income or lifestyle.

In Chapter 2 we provided an overview of sources of data on a number of themes and variables not measured by the census (such as crime-and safety-related variables, health, deprivation, income and lifestyle information, etc.) but estimated on the basis of social survey or administrative data and, in many cases, by combining them with census data with the use of small-area estimation methods. Such data sources are made available to meet a very strong need for small-area data from academics, private and public sector organisations and government departments. Again our examples here are drawn from the UK – we hope the reader can search for the equivalent in their home country. The important point is how many of these variables can be mapped and analysed in a GIS framework to provide important insights into spatial patterns of policy-relevant socio-economic variables.

There is also a wealth of UK social survey data that can be used, as is demonstrated in this chapter, in combination with census and other small-area data to produce small-area information on variables that are not available from other sources as well as synthetic populations which can be analysed to study interdependencies between different variables at the individual level (e.g. age, health status), household level (e.g. household type, household income) and different area-level variables (e.g. availability and quality of local amenities, access to job markets, etc.).

There are numerous UK socio-economic surveys of households and individuals that can be used to study these interdependencies but with limited scope for GIS analysis. The outputs of most of these surveys are typically released at relatively coarse levels of geography (e.g. region or local authority district level geographies). Among the most widely used socio-economic surveys in the UK are the New Earnings Survey (conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS)), which records employment data of a relatively large sample of employees. Further, the Family Expenditure Survey (FES) has been widely used for policy analysis. The FES is a continuous survey of household expenditure and income carried out by the ONS (sample size 10,000 households). It should be noted that the FES was combined with the National Food Survey from 2001 and renamed to the Expenditure and Food Survey. It is now known as the Living Costs and Food Survey.2 Among the survey’s topics are:

■ food consumption and nutrition;

■ expenditure on goods and services, with considerable detail in the categories used;

■ income, including details about the sources of income;

■ possession of consumer durables and cars;

■ housing.

Further, the Family Resources Survey3 (FRS) is a continuous survey that was launched in October 1992 by the Department of Social Security (ONS, 2000b; Dhanecha et al., 2003). The FRS has a relatively large sample size (around 26,000 households per year). The FRS includes:

■ basic household and individual characteristics (tenure, ethnic origin, employment status, etc.);

■ housing costs (rents, mortgages, Council Tax, water and sewerage charges, insurance);

■ household income (including benefit receipt, unearned income, pensions, etc.);

■ other costs (travel to work costs, childcare costs, maintenance payments, etc.);

■ ownership of vehicles and consumer durables.

(ONS, 2000b; Dhanecha et al., 2003)

The General Lifestyle Survey (GLS), formerly known as the General Household Survey, was conducted from 1971 to 2012 (UK Data Service, 2017a) and covered five ‘core’ subjects: population and family information, housing, employment, education and health. In addition, special topics were added from year to year. In 1998 these supplementary topics included smoking, drinking, hearing, contraception and day care. Questions related to elderly people were also repeated from earlier years, with the results published as a separate report ‘People aged 65 and over’ (UK Data Service, 2017a). The GLS can be used to explore the relationships between income, housing, economic activity, family composition, fertility, education, leisure activities, drinking, smoking and health. In addition to regular ‘core’ questions, certain subjects are covered periodically, such as:

■ family and household formation;

■ health and related topics;

■ use of social services by the elderly and participation in sports and leisure activities.

Another widely used survey for labour market analysis is the Labour Force Survey (LFS) which is conducted by the ONS. The survey was biennial from 1973 to 1983. Since 1984 the LFS has been conducted annually, and since 1992 quarterly, with around 40,000 sampled households (ONS, 2015; UK Data Service, 2017b). The LFS has a panel design and every household is interviewed for five waves. The LFS asks a range of questions including:

■ household composition;

■ housing tenure;

■ ethnicity;

■ education and training;

■ employment, unemployment and job search activities;

■ reasons for not wanting to work;

■ income;

■ labour mobility;

■ travel to work;

■ trade union membership;

■ current working conditions;

■ hours of work and health (sickness, accidents and health problems/disabilities).

One of the most comprehensive surveys in Britain is the BHPS/Understanding Society,4 which is an annual survey of the adult population of the UK, drawn from a representative sample of over 5,000 households. The aim of the survey is to deepen the understanding of social and economic change at the individual and household levels in Britain, as well as to identify, model and forecast such changes, their causes and consequences in relation to a range of socio-economic variables (Taylor et al., 2001). Appendixes 6.1 and 6.2 outline the core household and individual questions asked in the BHPS questionnaires (and the basis for the Understanding Society Survey, which is also known as the UK Household Longitudinal Study). These questions have generated a wealth of socio-economic and demographic variables, which make the BHPS unique in that it contains almost all the variables contained in most other national social survey data in Britain. However, as is the case with all other large surveys, BHPS gives information at relatively coarse levels of geography.

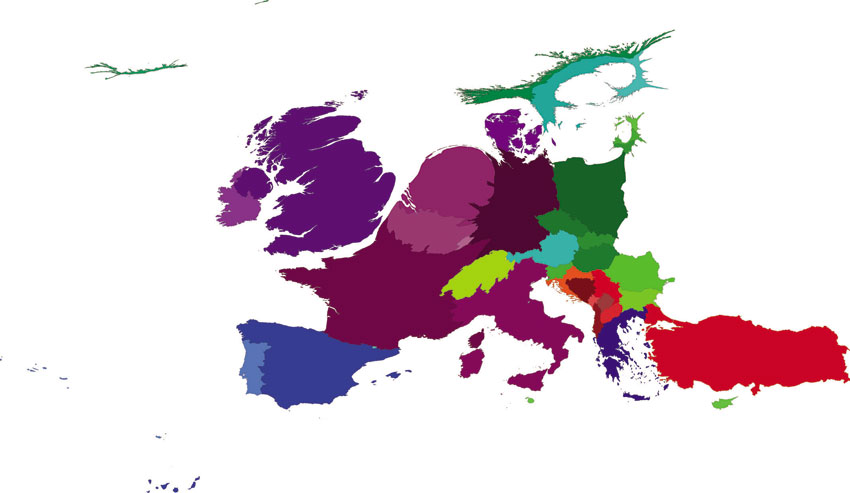

Figure 6.1 Geographical distribution of subjective happiness in Europe (see Figure 3.6 for details of colour scheme used)

Source: Ballas et al. (2014), based on data from the European Values Survey

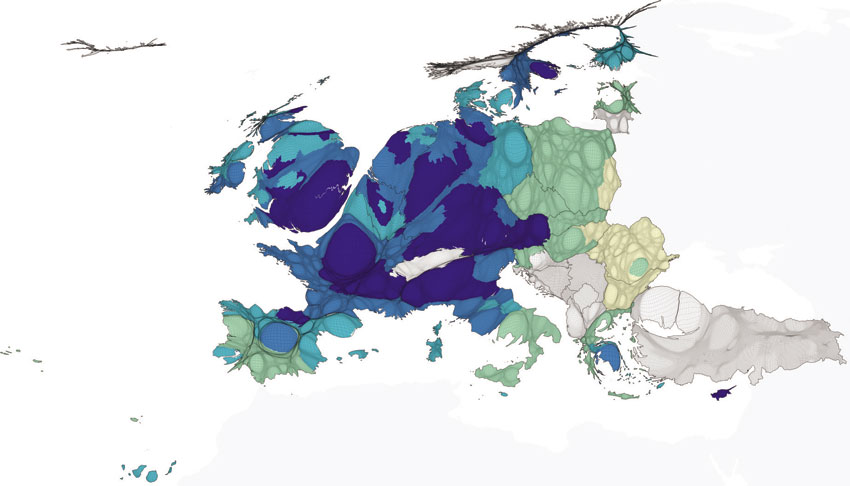

The UK social survey data sets described above can be used in many cases to obtain data on variables such as average income or more unusual data such as life satisfaction and subjective happiness at national or regional level. For instance, Figures 6.1 and 6.2 present cartographic representations (using the methods described in Chapter 3) of national subjective life satisfaction in Europe (based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) data) and regional disposable income (based on data from the European Values Survey).

Figure 6.2 Net adjusted disposable income of private households (purchasing power consumption standard), 2007

Source: Ballas et al. (2014)

Overall, there are very few sources of geographically detailed microdata sets, but it is increasingly possible to use GIS and related methods to combine such surveys with local area (within regions and cities) data. The remainder of this chapter provides an overview of these methods as well as new approaches that utilise online data sources. In addition, the accompanying practical provides data and a worked example of how to apply one of the methods described below.

Generating indirect non-survey designed estimates

The simplest approach to combining national social survey data with small-area information is to obtain small-area total numbers from the census on variables that could be correlated with a ‘target variable’ to be estimated (e.g. income would be correlated with ‘occupational classification’). The next step is to obtain information at the national or sometimes regional level on the same variable cross-tabulated by the census variable. For example, Figure 6.3 shows the average monthly earnings in euros (before tax) by broad occupational classification in the UK according to the EU-SILC. These data can be matched with suitable small-area data from sources such as the census of population. For instance, the UK census of population provides information on total population by broad and more detailed occupation group categories. Table 6.1 presents these broad categories.

Table 6.1 Census of population small-area broad occupational groupings

1. |

Managers, directors and senior officials |

2. |

Professional occupations |

3. |

Associate professional and technical occupations |

4. |

Administrative and secretarial occupations |

5. |

Skilled trades occupations |

6. |

Caring, leisure and other service occupations |

7. |

Sales and customer service occupations |

8. |

Process, plant and machine operatives |

9. |

Elementary occupations |

Source: UK Census of Population Table (QS606EW) Occupation (Minor Groups) (QS606EW) obtained via https://neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk

The data sets from the EU-SILC and the census of population illustrated in Figure 6.3 and Table 6.1, respectively can be used to generate what can be described as ‘indirect non-survey designed estimates of earnings’ at the small-area level. This can be achieved by multiplying the average income for each occupational group shown in Figure 6.3 with the total number of people belonging to this group (or a similar group, if there is no direct match). It should be noted that both the EU-SILC and the census of population data sets contain more detailed information on occupational groupings that could be used (more than 100 sub-groups) to provide more sophisticated estimates. In addition, when suitable data are available it is also useful to combine different variables (e.g. calculate average earnings by socio-economic occupation and by age and sex and then multiply this by the respective total numbers at the small-area level).

Figure 6.3 Gross monthly employee earnings by occupation category in the UK, 2011

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the EU-SILC

The simple approach described above can be adopted to estimate any other variable at the small-area level, as long as there is some association (according to relevant theories or appropriate statistical analysis) between the variable to be estimated and the relevant variables available at the small-area level. The steps to be adopted with this simple approach can be summarised as follows:

■ Obtain small-area total numbers from the census on variables that could be correlated with a ‘target’ variable (e.g. income would be correlated with ‘occupational classification’).

■ Obtain information at the national or sometimes regional level on the same variable cross-tabulated by the relevant census variable (e.g. earnings by occupational classification).

■ Multiply the known census totals by average value for each area.

The accompanying practical for this chapter provides an example of how this method can be applied to estimate expenditure for small areas. The next section discusses more sophisticated approaches to small-area estimation that are based on suitable statistical analysis that identifies small-area variables that are most likely to be correlated with a ‘target’ variable to be estimated.

Statistical model-based estimates

The simple approach described above can be useful if there are limited resources, but it does not take advantage of geographical models that can be used for a more sophisticated estimation of information at the small-area level using GIS-related methods. In particular, there has been a great deal of more sophisticated modelling work conducted by geographers and regional economists who have been involved in the construction of small-area income estimation models. In contrast to the above simple approach, these modelling approaches explore the relationship between the target variable to be estimated (typically income) and a wide range of other socio-economic and demographic variables. In this section we give a flavour of these developments over the past 20 years drawing on and updating a review of relevant work (Ballas et al., 2006a). Most of these developments are based on statistical analysis and modelling which are increasingly embedded in GIS proprietary software. For instance, one of the key methods is regression analysis which can be used to understand, model and predict a variable (such as income, known as the dependent variable) on the basis of the observations of explanatory (or independent) variables. For example, as also discussed in the previous section, income is correlated with variables such as educational attainment, socio-economic classification and occupational status, employment status and age. Regression analysis is typically employed to identify the causes of particular phenomena (e.g. the relationship between income inequality and crime) at different geographical levels and it is a standard tool that is now embedded in GIS software packages such as ArcGIS5 (see Figure 6.4).

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the standard regression models have relatively limited potential for GIS-based analysis, as they do not take into account spatial dependencies between observations and potential local variations in statistical relationships. Such issues can be addressed with the use of more ‘geographically aware’ methods such as Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), which involves the estimation of local regression equations (Brunsdon et al., 1996; Fotheringham et al., 2002) and Anselin’s (1995) Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA). There is specialised stand-alone software that can be used to apply these methods but there are also features in proprietary GIS packages such as ArcGIS that enable GWR6 and LISA7 analysis. These are very powerful toolkits for the study of local variations and associations between variables, but there a number of alternative approaches building on different ‘flavours’ of statistical modelling (including regression) that are particularly aimed at estimating small-area information and, in particular, income. These are discussed in some detail in the remainder of this section.

Figure 6.4 Regression in GIS as explained by ArcMap instruction manuals

Among the early most sophisticated and robust small-area income estimation modelling approaches in the UK is the work of Bramley and Smart (1996) who developed a formal model capable of estimating local (at local authority district level) income distributions on the basis of census data, as well as data from the UK FES and the UK National Online Manpower Information System.8 Their modelling approach was based on classifying FES households by type and economic activity (e.g. no household members in employment, one household member in employment, 2+ members in employment) obtained from the census at the local authority district level. To each household type they then allocated a median weekly income based on the data shown in Table 6.2. One of the key characteristics of their model was the ability to estimate proportions of households by local authority districts that have an income below a given level. Bramley and Smart (1996) applied their modelling approach and generated results for England. They also validated their results, by comparing their estimates with FES data at the national level, as well as regional and district income data from the Inland Revenue, and found that their model estimates fitted these data reasonably well.

Bramley and Lancaster (1998) refined this model by incorporating housing tenure disaggregation. They have also modified model parameter values on the basis of the analysis of microdata specific to Scotland, before implementing the model for Scottish districts and sub-district areas (postal sectors). They then tested the predictions of the model for Scotland against various external data sets at different geographical levels. An additional important development in their model was a method of updating and projecting the estimates forward. The method was based on the utilisation of a wider range of data including the LFS, New Earnings Survey, claimant unemployment data, Scottish Office household projection data, housing stock by tenure and house prices. For instance, they used 1992 and 1995 district-level data from the LFS to calculate the rate of change for a number of indicators (economic activity rates, unemployment rates, part-time workers, industry and occupation structure). They then applied these rates to the 1991 census values in order to provide updated data for their model. Another example of small-area estimation is the work of Rusanen et al. (2001, 2002) who examined income data in Finland and carried out an analysis of mean taxable incomes per household throughout the 1990s at a 1 by 1 km grid cell resolution, comparing their results with income data at postal district and municipality levels. They suggested that the smaller the areal unit used, the greater the income differences, and vice versa, and concluded that the results of analyses based on different areal units cannot necessarily be regarded as comparable. Hamnett and Cross (1998) used GHS data and New Earnings Survey data to examine the existence and extent of income polarisation in London. Their research suggested that the evidence for polarisation was relatively weak, and that where polarisation exists it is asymmetric, with much greater growth in the size of groups at the top of the earnings distribution than at the bottom.

Table 6.2 Household groupings and income distributions used by Bramley and Smart (1996), based on 1991 Family Expenditure Survey

Household type |

Composition (%) |

Median income per week |

Single elderly |

14.6 |

£92.30 |

Single adult |

12.8 |

£217.30 |

Lone parent + child |

4.3 |

£109.20 |

Elderly couple |

9.8 |

£177.90 |

Couple/2 adults |

22.1 |

£405.70 |

Couple + 1 child |

8.3 |

£392.20 |

Couple + 2 children |

10.6 |

£413.10 |

Couple + 3+ children |

5.2 |

£391.30 |

3+ adults |

12.1 |

£517.50 |

All households |

100 |

£296.80 |

Another relevant (and more recent) example is the work of Longley and Tobon (2004) who presented developments in the provision and quality of digital data, arguing that these developments create new possibilities for spatial and temporal measurement of the properties of socio-economic systems at finer levels of granularity. In addition, they suggest that the ‘lifestyles’ data sets collected by private sector organisations in the UK and the US provide one such prospect for better inferring the structure, composition and heterogeneity of urban areas. Using a case study of the city of Bristol they compare the patterns of spatial dependence and spatial heterogeneity observed for a small-area income measure with those of the census indicators that are commonly used as surrogates for it.

Using similar ‘lifestyle’ data, the CACI consultancy reported findings on household wealth in the UK. In particular, CACI publishes an annual report on the ‘Wealth of the Nation’, examining average household income by broad geographic regions such as county or local authority and exploring local concentrations of wealth and poverty by ranking local neighbourhoods with the highest proportion of households earning a lot, or very little. CACI estimates household income distributions at geographical level down to unit postcode based on four million market research records, ACORN (their household-level geodemographic classification), national census and survey data, and statistical modelling. CACI weights household records from commercial data sets so that they match target distributions by ACORN class, postcode area and income band.

CACI’s reports (2005) are typically based on PayCheck, a system that provides estimates of gross household income (including investment income and social security) right down to the level of postcode. In particular, PayCheck is CACI’s estimate of household income at postcode level. It is based upon government data sources together with income data for millions of UK households collected from lifestyle surveys and guarantee card returns (CACI, 2005). The core directory provides estimates of mean gross household income by postcode and a banding of these mean incomes, which can be used for profiling or classifying postcodes. The extended directory provides more detailed information on the expected income distribution within each postcode. A similar source of household income information is the Experian database, which is available for academic use (Webber, 2004; Census Dissemination Unit, 2005). This database comprises the Mosaic UK household classification data, classifying all UK households into 11 groups, 61 types and 243 segments and is updated every year. It also comprises median household income data which are estimated on the basis of a multi-stage process that predicts personal and household income for a number of standard employment types using survey data (including MORI’s Financial Tracking Survey). Nevertheless, it should be noted that a serious flaw of both CACI and Experian data is the dependence on lifestyle surveys and postcode addresses (with associated biased response rates) and a reliance on a small number of lifestyle categories to model income. McLoone (2002) provides a detailed discussion and critique of CACI’s data.

Williamson and Voas (2000) pointed out that CACI small-area income estimates might be the best that have been produced due to the size of the underlying data set. Nevertheless, it is very difficult to evaluate the results and the techniques, given that these are not in the public domain (with the exception of the methods used by Experian9). Williamson and Voas (2000) and McLoone (2002) also stress that possible weaknesses of the CACI approach include an over-reliance on geodemographic classification and an analysis of geographical context restricted to postcode area level.

In the US, Fay and Herriot (1979) were among the first researchers to use a statistical approach to estimate income for small areas (defined as ‘areas with a population of less than 1,000 residents’). More recently, Fisher (1997) presented the ‘Small-area Income and Poverty Estimates’ (SAIPE) programme, which aimed at estimating median household income for states and counties, as well as poverty for states, counties and school districts. These estimates were based on statistical models that used decennial census data, household survey data, administrative records data and population estimates. Gee and Fisher (2004) discuss ways of identifying the degree of error in the estimates generated by this method. Cressie (1995) also discussed geographical data on income in the US, suggesting that the data published by the US Census Bureau at the county level are often a noisy representation of the true geographic distribution of rates over the small areas, and he presented a Bayesian statistical method for smoothing raw rates.

Lynch (2003) also used US census data in combination with US Internal Revenue Service data in order to produce estimates of income levels and income inequality in the United States for 1988, 1995 and 1999. He analysed trends in national and regional income inequality and income levels between 1988 and 1999. At a smaller area level, Cloutier (1995, 1997) explored the inter-urban variation in family income distribution in the 1980s. Cloutier (1995) argued that the estimation of percentile incomes within intervals reported by the Census Bureau has often been carried out under the assumption that incomes are uniformly distributed. Using log-normal extrapolation methods Cloutier (1995) demonstrated that income might be significantly underestimated if the assumption is applied to lower level percentiles in the black family income distribution and suggested that analysis based on US census data about the level and determinants of the relative income of poor black families could be misleading.

In a more applied context, Cloutier (1997) used similar methods to demonstrate that urban development, rising female-headship, a widening educational distribution and changes in the industrial and occupational mix were major contributing factors to rising inequality in US metropolitan areas. Hammer et al. (2003) studied the impact of income estimates derived using the US Census Bureau SAIPE method upon the development of a ‘distressed county’ index that was used by the US Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). In particular, they evaluated the potential impact of incorporating the SAIPE estimates into the index and they suggested that these would alter the index but not to a radical degree. They also suggested that combining the SAIPE point estimate and the SAIPE upper bound estimate in the determination of distressed status would achieve the objective of using more current estimates of poverty while reducing the negative consequences of using an estimate of poverty with greater statistical variation than decennial census-derived estimates.

As can be seen thus far from the examples discussed above, there have been numerous attempts worldwide to estimate income at geographical levels that are much smaller than the official statistical units at which survey-based data are typically available.

The best way of validating small-area estimation methods is by comparing estimated or modelled data with actual census or census-style survey data. This became possible in England and Wales when the ONS tested an income question during their large-scale census rehearsal in April 1999, following a survey of census users (Rees, 1998). The question was dropped from the final version of the census form used in 2001 due to concerns about potential negative impacts on response rates. However, Williamson and Voas (2000) conducted research for the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) between 2000 and 2001 (Williamson, 2005) and carried out analysis of these rehearsal data in order to explore alternative small-area income imputation methods. Figure 6.5 shows the census rehearsal data income distribution.

This distribution approximates a log-normal pattern, which is what should be expected according to relevant literature in economics. Nevertheless, it is interesting to explore this distribution in different areas. Figure 6.6 shows the income distribution for enumeration districts classified on the basis of overall income. As can be seen, the pattern varies considerably. Also, as Williamson (2000) points out, there are considerable variations in households in different income bands by area. In particular, at electoral ward level, the proportion of household heads in the top income band is on average 9.1%, ranging from 2.8% to 21.6% (Williamson and Voas, 2000). In addition, Williamson and Voas suggest that 89% of enumeration districts contained one or more household heads who were in the top income decile of the population.

Figure 6.5 Census rehearsal household income distribution

Source: After Williamson and Voas (2000)

Williamson’s research project made extensive use of the census rehearsal data in order to evaluate existing and proposed small-area income estimation methods. He assessed the efficacy of alternative small-area imputation strategies when applied to sub-district spatial units. In particular, he evaluated the census rehearsal data set and evaluated established small-area income estimation methods. Williamson suggested that by far the most effective simple proxy for income is the proportion of the economically active population in National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) categories 1 and 2 (Managerial and professional occupations). He also suggested that this finding applies regardless of whether mean income is measured per person, per adult or per number of persons in the household. The proportion of NS-SEC 1+2 captured 74% to 81% of the observed variation in income between enumeration districts (areas with an average size 100 households). The only income measure for which a better alternative exists is mean total household income, for which the proportion of households with no car offers better performance. Williamson also explored the association of a range of deprivation indexes (such as those discussed in Chapter 5) with income data from the census rehearsal exercise. According to his analysis, these indexes, based on the combination of a number of proxy measures, performed less well than % NS-SEC 1+2. Williamson’s results suggested that only in certain circumstances can even commercial geodemographic (area) classifications match the performance of the simple indicator % NS-SEC 1+2.

Voas and Williamson (2000) and Williamson’s (2005) research were evaluated by Patrick Heady of the UK ONS and his colleagues who consequently built a regression synthetic estimation fitted using area-level covariates approach (Heady et al., 2003).10 Their modelled estimation method involves combining survey data with other data sources that are available on an area basis and is underpinned by the area-level relationship between the survey and auxiliary variables (usually administration data or census data). In this context, Heady et al. (2003) modelled ten variables at the small-area level: household income from the FRS, household income from the GHS, a measure of social capital, children from ethnic minorities, number of people to help in a crisis, single-parent families, overcrowding and three measures of poor health. They developed a regression model that was used to estimate ‘average weekly household’ income at the electoral ward level in England and Wales on the basis of the following predictors:

■ the social class of the ward population;

■ household type/composition;

■ regional/country indicators;

■ the employment status of the ward population;

■ the proportion of the ward population claiming DWP benefits;

■ the proportion of dwellings in each of the Council Tax bands in a ward.

Figure 6.6 Income distribution of household representatives in different local neighbourhoods (census enumeration districts) classified by income

Source: After Williamson and Voas (2000)

Their model-based approach is based on finding a relationship between weekly household income (as measured in the FRS) and covariate information (usually from census or administrative sources) for the wards that are represented in the FRS. The Small-area Estimation Project (SAEP) methodology has been applied by ONS to produce ward-level estimates of income in Britain with the latest data (at the time of writing this book) in 2011/12.11

Geosimulation and spatial microsimulation

In this section we discuss ways of building on the experience obtained through the studies reviewed so far, in order to produce improved and more detailed small-area estimates of variables that are not available at small-area level. So far we have described a wide range of methodologies aimed at estimating income at various geographical scales in different contexts. Most of these regression-based modelling approaches to small-area estimation have been very successful in identifying census and other variables that are useful for predicting a target variable such as average income at various scales. However, they are not suitable for estimating combinations of variables (e.g. number of low-income elderly individuals with no access to a car; or numbers of households with dependent children below the poverty threshold) or proportions of households or individuals earning below or above particular income thresholds. Such estimates are particularly useful for the geographical analysis of the impacts of national public policies as well as area-based policies. In this section we present more sophisticated geographical approaches that can be used to produce small-area microdata including a wide range of variables (and combination of variables) that include income but also other information, and which can support the spatial analysis of national social policies as well as urban and regional policies. In particular, we present GIS-based research efforts that are aimed at creating simulation models that can be used for the estimation of the spatial impacts of social policies, as well as their socio-economic impact, in order to address the need for spatial analysis of national social policies. These geographical simulation methods are conceptually very relevant to popular life simulation computer games such as SimCity and the Sims, but, instead of using game-based rules and hypothetical imaginary data on the synthetic characters of the game, it involves the merging of small-area statistics (such as census of population data) and social survey data to simulate a population of individuals within households (or different geographical units), whose characteristics are as close to real populations as it is possible to estimate. These methods can also involve the development and use of computer agent-based models (Heard et al., 2015) and dynamic microsimulation models which involve forecasting past changes forward to produce the best estimate possible of an individual’s circumstances in the future – were current trends to continue – or under different policy scenarios.

Microsimulation is a technique that has been broadly developed and used by economists and other social scientists.12 In particular, economists have long been involved in the development of microsimulation models that are capable of modelling the impact of national government policies. The results of national (aspatial) microsimulation models are widely quoted in the media when covering the possible impact of government budget changes upon different types of households. Microsimulation models aim to build large-scale data sets on the attributes of individuals or households (and/or on the attributes of individual firms or organisations) and to analyse policy impacts on these micro-units; by permitting analyses at the level of the individual, family or household they provide the means of assessing variations in the distributional effects of different policies (e.g. see Mitton et al., 2000; Redmond et al., 1998). However, these models have been very limited in terms of geographical analysis capacity and this was mostly due to the lack of good quality geographical data, issues of computational power and software developments. In particular, until very recently there were very few sources of geographical socio-economic data. Even today, with a very few exceptions, there are no very small-area population microdata, which are the standard data sets used by sophisticated economic microsimulation models.

Microsimulation models become geographical when spatial information about the simulated entities is available (or estimated). Spatial microsimulation involves the creation of large-scale population microdata sets and the analysis of the impacts of any policy changes that change the attributes contained in these micro databases in some way. In other words, adding spatial detail to traditional microsimulation involves creating geographically referenced microdata that refer to a particular locality, to a geographically defined and restricted area. Since there are very few sources of geographically detailed microdata, there is a need to create these data using spatial microsimulation techniques by merging census and survey data to simulate a population of individuals within households (for different geographical units) whose characteristics are as close to the real population as it is possible to estimate.

Various types of spatial microsimulation models can be distinguished. For instance, there are static models that are based on simple snapshots of the current circumstances of a sample of the population at any one time, and dynamic models that vary or age the attributes of each micro-unit in a sample to build up a synthetic longitudinal database describing the sample members’ lifetimes into the future. The main characteristic of dynamic models is that they incorporate behavioural responses under different policy scenarios.

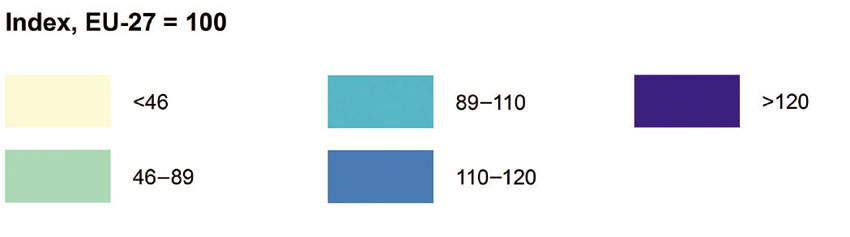

As noted above, spatial microsimulation involves the creation of large-scale population microdata sets and the analysis of policy impacts at the micro level. Population microdata contain information on individuals rather than aggregate data. Population microdata can be divided into individual microdata that contain information on individuals, household microdata that might contain household information only and household microdata that might contain individual and household information. For example, the BHPS/Understanding Society data that we described earlier can be used in combination with census small-area data to estimate health-related variables at the small-area level, as well as to explore the interdependencies of these variables with socio-economic variables such as income, social class, access to health services, etc. The BHPS/Understanding Society is a representative longitudinal survey on the social situation of private households and can be presented in the format of a list of individuals within households (see Tables 6.3 and 6.4).

Spatial microsimulation techniques involve the merging of survey data such as the BHPS with census and other geographical area data to simulate a population of individuals within households (for different geographical units), whose characteristics are as close to the real population as it is possible to estimate. In other words, geographical microsimulation models simulate virtual populations in given geographical areas, so that the characteristics of these populations are as close as possible to their ‘real-world’ counterparts. One of the major advantages of microsimulation is that it can be a substitute for conducting detailed surveys to produce survey data such as the BHPS described above at the small-area level.

The spatial microsimulation method typically involves three major procedures:

■ The construction of a microdata set from samples and surveys.

■ Static what-if simulations, in which the impacts of alternative policy scenarios on the population are estimated: who would benefit from a particular local or national government policy? Which geographical areas would benefit the most?

■ Dynamic modelling, to update a basic microdata set and future-oriented what-if simulations.

Table 6.3 The BHPS microdata format

Table 6.4 Variable descriptions for Table 6.3

Person |

Person number |

*HID |

Household identifier (number of household to which the listed individual belongs) |

PID |

Person identifier (a unique number to identify the individual) |

*AGE12 |

Age at 1/12/ * |

SEX |

Sex |

*JBSTAT |

Current labour force status (e.g. self-employed, in paid employment, unemployed, family care, etc.) in year * |

*HLLT |

Health status in year * |

*QFVOC |

Vocational qualifications in year * |

*Tenure |

Tenure status in year * |

*JLSEG |

Socio-economic group: last job (in year *) |

The first procedure can also be defined as static spatial microsimulation. This involves the reweighting of an existing microdata sample (which is only available at coarse levels of geography), so that it would fit small-area population statistics tables. For instance, an existing microdata set such as the BHPS described above can be reweighted to ‘populate’ small areas. The BHPS provides a detailed record for a sample of households and all of their members. Reweighting methods aim to sample from all the microdata records to find the set of household records that best matches the population described in the UK small-area statistics. First, a series of small-area tables (e.g. from the census or other sources) that describe the small area of interest must be selected. For example, a reweighting method would sample from the BHPS to find a suitable combination of households that would fit the statistical data in two hypothetical areas or neighbourhoods within cities and regions presented in Table 6.5.

The task would be to select the records of the BHPS microdata that best match these statistical descriptions using statistical matching or geographical microsimulation reweighting techniques. However, there is a vast number of possible sets of households that can be drawn from the BHPS sample. There is a wide range of techniques that can be employed to find a set that fits the target tables well. There are a number of alternative static spatial microsimulation approaches that are capable of generating small-area microdata based on estimation methods ranging from Iterative Proportional Fitting-based deterministic reweighting (Ballas, 2004; Ballas et al., 2005a, 2005c) and synthetic reconstruction (Ballas and Clarke, 2000) to combinatorial optimisation heuristic techniques such as simulated annealing (Williamson et al., 1998; Ballas et al., 2007b). These models also include systematic validation of the simulations by comparing simulated outputs to published data and in some cases also involve creating Graphical User Interfaces and Planning Support GIS systems (Ballas et al., 2007b; see Figure 6.7) that allow interactive visualisation and mapping of the outputs under different scenarios. Recent reviews of the state of the art and relevant developments are presented by Hermes and Poulsen (2012) and Tanton and Edwards (2013).

Table 6.5 A hypothetical small-area statistical data set for two areas

Small-area table 1 (household type) |

Small-area table 2 (economic activity of household head) |

Small-area table 3 (tenure status) |

Area 1 |

Area 1 |

Area 1 |

60 married couple households |

80 employed/self-employed |

60 owner occupier |

20 single-person households |

10 unemployed |

20 Local Authority or Housing Association |

20 other |

20 other |

20 rented privately |

Area 2 |

Area 2 |

Area 2 |

40 married couple households |

60 employed/self-employed |

60 owner occupier |

20 single-person households |

20 unemployed |

20 Local Authority or Housing Association |

40 other |

30 other |

20 rented privately |

Figure 6.7 Spatial microsimulation query results

Overall, these models result in the creation or synthesis of small-area population microdata which can be achieved by combining different small-area census cross-tabulations or by merging survey data such as census and other geographical area data to simulate a population of individuals within households (for different geographical units), whose characteristics are as close to the real population as it is possible to estimate. In other words, the models simulate virtual populations in given geographical areas, so that the characteristics of these populations are as close as possible to their ‘real-world’ counterparts. The simulation outputs can include a wide range of policy-relevant variables such as earned income, tenure status, household type, socio-economic group, consumption patterns, car ownership and so forth.

An example of a model that combines national survey data with small-area census data to estimate small-area microdata is the SimBritain model (Ballas et al., 2005a, 2005c) which adopts a so-called deterministic approach to reweighting survey microdata so that they fit given small-area statistics tables. In particular, this methodology was used to estimate a wide range of non-census variables (including household income) at the small-area level. This model has been used to assess the socio-economic as well as geographical impact of a wide range of national social policy changes in the UK (Ballas et al., 2007a; also discussed in more detail in the next section). Another example of such a model is the Microsimulation Modelling and Predictive Policy Analysis System (Micro-MaPPAS) (Ballas et al., 2007b – an example is shown in Figure 6.7) which is open-source software implementing a geographical microsimulation model which is capable of constructing a list of approximately 715,000 individuals living within households along with their associated attributes for any point in time (past or future) at very small-area levels (down to UK OAs, an average of 100 households). The technique applies a simulated annealing combinatorial optimisation algorithm to data from the census of population and national survey microdata. There is also ongoing work and recent developments aimed at producing freely available generic code and software that can be combined with GIS (see the Further reading and resources section at the end of this chapter).

Dynamic microsimulation involves forecasting past changes forward to produce the best estimate possible of an individual’s circumstances in the future – were current trends to continue, or were they to change under different policy scenarios. Dynamic microsimulation typically involves the modelling of behavioural and second-order effects. This can be carried out on the basis of calculated probabilities for a series of event changes that occur during the lifetime of individuals. Another aim of dynamic spatial microsimulation is the analysis of household and individual reactions and behavioural changes that might result from policy changes. This adds further to the complexity of the task.

The task becomes even more difficult when there are attempts to introduce geographical detail. Spatial dynamic microsimulation involves the behavioural modelling of individuals over time and at various geographical scales. It also involves the modelling of individual decisions that have a strong geographical element, such as migration. The latter is dependent on a series of individual characteristics such as age, socio-economic background and tenure.

Spatial dynamic microsimulation involves the modelling of different types of transitions on the basis of each individual’s attributes and circumstances. Nevertheless, one of the biggest problems associated with both spatial and non-spatial dynamic microsimulation is that they can be extremely complex and difficult to develop, implement and explain to policy practitioners who might be interested in using them. It has often been argued in the microsimulation literature that there is a need for transparency and simplicity in the construction of models. An alternative to the traditional comprehensive dynamic microsimulation models is to combine aggregate projection methods with the static microsimulation methods.

Table 6.6 depicts the steps that need to be followed in the procedure for allocating employment status and industry and modelling survival and migration. It should be noted however that the example depicted is simplified, in order to illustrate the process.

Table 6.6 A simple example of the microsimulation procedure for the modelling of migration and survival

Steps |

1st |

2nd |

… |

Last |

Age, sex and marital status and location (e.g. neighbourhood or small-area level)(given) |

Age: 25 Sex: Male Marital Status: single GeoCode: Neighbourhood 1 |

Age: 76 Sex: Female Marital Status: married GeoCode: Neighbourhood 2 |

… |

Age: 30 Sex: Male Marital Status: married GeoCode: Neighbourhood 3 |

Probability (conditional upon age, sex, location) of person to migrate |

0.30 |

0.05 |

… |

0.26 |

Random number |

0.2 |

0.4 |

… |

0.6 |

Migration status assigned on the basis of random sampling |

Migrant |

Non-migrant |

… |

Non-migrant |

Probability (conditional upon age, sex, location) of person to survive |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

|

Random number |

0.5 |

0.9 |

… |

0.4 |

Survival status |

Survived |

Deceased |

… |

Survived |

One of the inherent difficulties of such a task is to determine the interdependencies between individual attributes and events. For instance, the probabilities of an individual participating in the labour force might be conditional upon family status (e.g. having children). However, it could also be argued that family status depends on labour market status.

An additional difficulty associated with dynamic spatial microsimulation models is the lack of sufficient geographical data that would enable the simulation of interactions such as migration flows between areas (e.g. there are no microdata on migration that would enable a reasonably accurate simulation of migration into the future). Due to the lack of suitable data there have been very few examples of spatial microsimulation of dynamic events such as migration (e.g. Ballas et al., 2005b; Rossiter et al., 2009; Kavroudakis et al., 2013). Nevertheless there are ongoing efforts to develop dynamic spatial microsimulation methodologies building on previous work (e.g. the work of Harding et al. (2010) and Holm and Mäkilä (2013)) in order to project small-area populations in all study regions under different scenarios. The models to date include the so-called probabilistic dynamic modelling (e.g. see Ballas et al., 2005b), implicitly dynamic macro approaches (Ballas et al., 2005a) and econometric approaches. There is also great potential to link dynamic microsimulation with another conceptually similar type of individual-level modelling: agent-based models (ABM). As noted above, ABMs are normally associated with the behaviour of multiple agents in a social or economic system. These agents usually interact constantly with each other and the environment they ‘live’ or move within, and their actions are driven by certain rules. Although this methodology is conceptually very similar to microsimulation (where agents could be the individuals within the households), it has long been argued that ABM might offer a better framework for including behavioural rules into the actions of agents (including an element of random behaviour) and for allowing interactions between agents (Davidsson, 2000). There are a number of good illustrations in a geographical setting (Heppenstall et al., 2005, 2006, 2007; Malleson et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2008) and there is a research agenda to link these two complementary approaches more effectively. Spatial microsimulation could be used to give the agents in ABM their initial characteristics and locations, while ABM could then provide the capacity to model individual adaptive behaviours and the emergence of new behaviours (also see Boman and Holm, 2004).

Using GIS and spatial microsimulation for public policy analysis

Spatial microsimulation models are very powerful tools for the analysis of urban, regional or national government policies. There are numerous examples of applied spatial microsimulation models for national policy analysis by geographers and regional scientists in a wide range of fields including social policy (e.g. Ballas and Clarke, 2000; Ballas et al., 2007a; Chin et al., 2005), poverty small-area estimation and analysis (Ballas, 2004; Tanton, 2011), health (Edwards and Clarke, 2009; Morrissey et al., 2008; Tomintz et al., 2008), agricultural policy (Ballas et al., 2006b; Hynes et al., 2009), international migration (Rephann and Holm, 2004), educational policy (Kavroudakis et al., 2013) and crime analysis (Kongmuang et al., 2006). In this section we give just a small flavour of how GIS and spatial microsimulation applications can be used to estimate and analyse policy-relevant information.

One of the key application areas of spatial microsimulation involves the estimation of small-area income distributions and the use of these estimates for policy analysis. Here we give a couple of examples of spatial microsimulation models that have been used to that end. We begin with the SimBritain model (Ballas et al., 2005a, 2007b) which combined small-area data from the UK census of population with the BHPS (described in more detail above) in order to produce a small-area survey microdata set for the geographical analysis of poverty and to explore the possible impacts of alternative social policy scenarios. The SimBritain model also involved the use of previous census data and appropriate population projection methods to estimate small-area microdata into future years. Table 6.7 shows an example of the analysis that was conducted at the small-area level (British electoral wards, parliamentary constituencies and metropolitan districts) with this model. The table shows households classified as very poor (all households with income below or equal to half of the median household income) in the city of York, UK, in different simulation years. As can be seen, the model outputs include variables that are not typically measured by the census of population (such as income, but also ‘loneliness’ and ‘happiness’ indicators) and cross-tabulations of as many variables as are deemed useful. For instance, Table 6.8 uses the outputs to draw pictures of the life of households in a similar way that Charles Booth and Seebohm Rowntree did in their original studies of poverty in London and York (as discussed in Chapter 5). It is possible to use the output of the method presented here to make some notes on the life of simulated households, and in this case of typical very poor households. This kind of information could also be used for the development of ABMs, which is a potential new development as discussed above.

Table 6.7 Living standards of very poor households

Very poor households |

1991 |

2001 |

2011 |

2021 |

Households (% of all households in York) |

17.2 |

17.3 |

17.8 |

21.3 |

Individuals (% of all individuals in York) |

14.7 |

13.3 |

13.7 |

20.5 |

Children (% of all children in York) |

21.8 |

17.7 |

18.6 |

38.5 |

Limiting long-term illness (as a % of all individuals in group) |

9.0 |

7.3 |

5.4 |

7.9 |

Elderly (over 64 years as a % of all individuals in group) |

30.1 |

32.0 |

33.3 |

44.2 |

Individuals in group with father’s occupation: unskilled (%) |

10.5 |

6.8 |

3.3 |

15.1 |

Reporting anxiety and depression (% of all individuals in group) |

10.6 |

10.3 |

7.4 |

3.1 |

Individuals who reported that they have no one to talk to (%) |

19.9 |

23.8 |

31.1 |

31.5 |

Promotion opportunities in current job (as % of individuals with a job) |

33.7 |

36.9 |

51.9 |

79.7 |

Feeling unhappy or depressed (%) |

19.9 |

19.0 |

18.2 |

12.1 |

Home computer in accommodation (%) |

1.4 |

1.0 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

House without central heating (%) |

26.1 |

21.4 |

21.4 |

31.1 |

Single-person households (%) |

61.6 |

76.0 |

77.9 |

64.4 |

Cars/households ratio |

0.23 |

0.32 |

0.38 |

0.40 |

Source: SimBritain model after Ballas et al. (2005c)

A key feature of spatial microsimulation models is the ability to perform what-if policy analysis. Again, we can use an application of the SimBritain model to illustrate how this is possible. Having estimated small-area microdata containing policy-relevant information (e.g. individual and household attributes and circumstances, levels of income) it is possible to estimate how many individuals and households are affected by particular policy changes. SimBritain was used to consider and analyse the geographical and socio-economic impact of a set of policies that were introduced by the British government in the late 1990s and which are described in detail in Appendix 6.3. The information provided in Appendix 6.3 was used to identify eligible individuals and households in the spatially microsimulated data set that was created by the SimBritain model. The next step was to estimate the total amounts by which each simulated eligible individual would be better off as a result of these policies and to then aggregate these to any geographical level deemed appropriate for mapping and analysis of any spatial patterns.

Figures 6.8 and 6.9 show examples of such mapping at the parliamentary constituency level in Wales and at the level of electoral ward in the city of York. In particular they depict the spatial distribution of the additional income per household by area which would result from implementing all the policy reforms shown in Appendix 6.3.

Table 6.8 Simulating the lives of individuals and households at small-area levels

Age in years |

Status |

56 and 52 |

Married couple, male aged 56, economically active but unemployed. Formerly employed as motor mechanic/auto engineer. Female aged 52, economically inactive. Food expenditure £25 per week. No car. House owned with mortgage. Highest educational qualification of male: GCE O levels. Female has no formal qualifications. |

46 |

Divorced, female, full-time personal services worker (hairdresser on seasonal/temporary job). Finding it quite difficult financially. No dependent children. Believes that all health care should be free, feeling unhappy or depressed. Has one car. Weekly household food expenditure £35. |

78 |

Divorced, female, retired sales assistant. Feels that there is no one who she could count on to listen if she needs to talk. Feels that she is just about getting by financially. No children, no car. Weekly food and grocery expenditure £20. |

34 and 21 |

Married couple, two children (aged eight and five). Two cars. Male has full-time job. He is self-employed (craft and related occupations – construction). Female is economically inactive (family care). Just about getting by financially. Household weekly food and grocery expenditure £40. |

34 and 33 |

Married couple, four children (aged 14, 13, 12 and 9). Male unemployed (previous job: food, drink and tobacco process operative). Female economically inactive (family care). Household weekly expenditure on food £80. |

30 |

Divorced, female, mother of three children (aged 11, 9 and 2), economically inactive (family care), weekly expenditure on food £20, no qualifications, formerly employed as a sales assistant. No car. House rented from local authority. |

Source: SimBritain model after Ballas et al. (2005c)

Figure 6.8 Estimated spatial distribution of additional income per household at the parliamentary constituency level for Wales

Source: SimBritain model after Ballas et al. (2005c)

Figure 6.9 Estimated spatial distribution of additional income per household by electoral ward for the city of York, UK

Source: SimBritain model after Ballas et al. (2005c)

These examples demonstrate how spatial microsimulation and GIS together can be used to highlight the importance of geography and to estimate the geographical as well as the social, temporal and economic impacts of policies. In particular, spatial microsimulation methods and GIS can be used to estimate the geographical impacts of social policies. These can then be compared with the respective impacts of area-based policies, as social policies can be seen as alternatives to area-based policies. Further, spatial microsimulation methods can be used to analyse social policy in a geographically oriented proactive fashion. For instance, spatial microsimulation can be employed to identify deprived localities in which poor individuals and households are over-represented, and then used to answer questions such as: ‘What social policy could be applied, which, all else being equal would most likely improve the quality of life of residents in the inner-city localities of a city?’ In other words, new social policies can be formulated on the basis of spatial microsimulation outputs. Spatially oriented social policies can be seen as a substitute or an alternative to traditional area-based policies and direct comparisons of their efficiency and effectiveness can be made.

There are ongoing developments in GIS and spatial microsimulation for policy analysis. A recent example is the SIMALBA13,14 model of the Scottish population and a recent application aimed at modelling the geographical impacts of proposed British national fiscal policies, focusing on the capital of Scotland, Edinburgh, and the largest city, Glasgow (Campbell and Ballas, 2013). Using a similar approach to the one adopted in SimBritain, SIMALBA combines data from the Scottish Health Survey with small-area census data to generate policy-relevant small-area microdata. These microdata can then be used to explore alternative proposed national government policies. One of these proposed policies that was considered and analysed is the introduction of a tax rate of 50% on personal income in the UK for higher incomes. SIMALBA was used to estimate the spatial distribution of people who would be affected by this change and mapped them at the OA level (neighbourhood level). Figure 6.10 shows the estimated distribution of people (at the neighbourhood level) in the city of Edinburgh who earn over £150,000 per year and who would be liable for a 50% rate of income tax if it were to be introduced in Scotland.

Figure 6.10 Simulated percentage earning over £150,000, Edinburgh, UK: quintiles

Source: Campbell and Ballas (2013)

Another application area that relates to adding a geographical dimension to debates around the importance of measuring quality of life is where spatial microsimulation has been used to estimate personal happiness and quantify and estimate its value for different types of individuals, living in different areas. As Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen points out:

A person who has had a life of misfortune, with very little opportunities, and rather little hope, may be more easily reconciled to deprivations than others reared in more fortunate and affluent circumstances. The metric of happiness may, therefore, distort the extent of deprivation in a specific and biased way.

(Sen, 1987: 45)

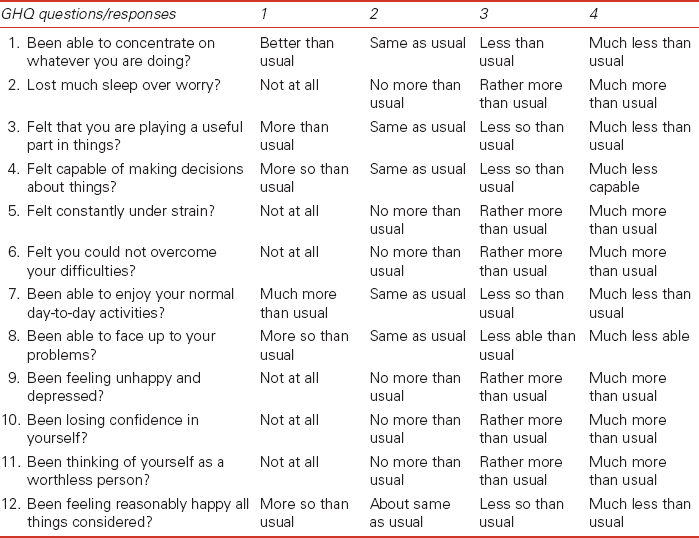

Table 6.9 Measuring subjective well-being in the BHPS: the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) set of questions as they appear on the BHPS questionnaire

Spatial microsimulation can be ideally suited to estimate happiness, since the degrees of well-being vary significantly between different individuals (different people are made happy by different things, life-courses, etc.). ‘SimHappiness’ (Ballas, 2010) was used to that end, combining data from the BHPS (and especially the subjective happiness and well-being variables generated from responses to the questions described in Table 6.9) and the UK census of population to add a geographical dimension to happiness research (such as the research on happiness by Clark and Oswald, 2002; Blanchflower and Oswald, 2004; Layard, 2005). SimHappiness was developed to estimate the geographical distribution of individual contentment through the 1990s across Britain. Figure 6.11 shows an output of this model, showing the estimated geographical distribution of happiness in Wales (at the level of Welsh Unitary Authorities).

Figure 6.11 Estimated geographical distribution of happiness (% happy more than usual) in Wales, 2001

Source: After Ballas (2010)

This chapter has presented a number of methods for the estimation of policy-relevant geographical information at various spatial scales. A key argument and message that is particularly prominent is that it is increasingly possible to use GIS and related spatial modelling methods to adopt a geographical approach to national policy analysis. The methods presented in this chapter (and especially the spatial microsimulation models) can be used to estimate the geographical distribution of a wide range of extremely policy-relevant social and economic variables. The accompanying practical shows how it is possible to make a start towards estimating and mapping small-area data using GIS. This provides a basis for the use of more advanced methods such as spatial microsimulation which enable the estimation of small-area microdata that can be re-aggregated or disaggregated geographically to provide estimates at any spatial level deemed appropriate for policy analysis as demonstrated in the practical. Although these methods are not available as part of proprietary GIS packages, there are stand-alone open-source GIS-based applications such as Micro-MaPPAS (Ballas et al., 2007b) as well as available software and data (see Further reading and online resources section for more information).

The accompanying practical (Practical 2: Combining survey and small-area data) makes use of some of the approaches discussed in this chapter in order to estimate the spatial distribution of consumer expenditure. Specifically, you estimate small-area expenditure on groceries, combining counts of households and surveyed expenditure rates, which vary by geodemographic classification. We also explore how to convert data between different geographies, and how to create high-quality cartographic outputs.

Notes

1 www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/census/2011/how-our-census-works/how-we-took-the-2011-census/how-we-collected-the-information/questionnaires--delivery--completion-and-return/2011-census-questions/index.html.

2 www.ons.gov.uk/surveys/informationforhouseholdsandindividuals/householdandindividualsurveys/livingcostsandfoodsurveylcf.

3 www.gov.uk/government/collections/family-resources-survey--2.

4 www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/.

5 E.g. see www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=71a65d35688a4502b123cbdfc99afdee.

6 http://webhelp.esri.com/arcgisdesktop/9.3/index.cfm?TopicName=Geographically%20Weighted%20Regression%20(Spatial%20Statistics).

7 http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.3/tools/spatial-statistics-toolbox/h-how-cluster-and-outlier-analysis-anselin-local-m.htm.

9 http://census.ac.uk/cdu/experian/household%20income.pdf.

10 Williamson’s ESRC report in 2005, reported on a research project carried out between 2000 and 2001. Heady and colleagues are mentioned in this report with regard to the dissemination of the findings.

11 www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/Info.do?m=0&s=1446935569123&enc=1&page=analysisandguidance/analysisarticles/small-area-model-based-income-estimates.htm&nsjs=true&nsck=false&nssvg=false&nswid=1600.

12 Microsimulation was first introduced in Orcutt (1957).

13 Sim referring to simulation, and Alba meaning ‘Scotland’ in Scottish Gaelic.

Further reading and online resources (including free software)

All website URLs accessed 30 May 2017.

■ Combinatorial Optimisation software (including dummy data set and associated documentation) by Paul Williamson (University of Liverpool): http://pcwww.liv.ac.uk/~william/microdata/CO%20070615/CO_software.html.

■ Iterative Proportional Fitting and integerisation R code and data: Lovelace, R., & Ballas, D. (2013) ‘Truncate, replicate, sample’: A method for creating integer weights for spatial microsimulation, Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0198971513000240 (open-access article including publicly available R code and data).

■ A recent review of the state of the art and research challenges by Adam Whitworth (University of Sheffield): Whitworth, A. et al. (2013) Evaluations and Improvements in Small Area Estimation Methodologies. Discussion Paper. NCRM www.ncrm.ac.uk/research/NMI/2012/smallarea.php and http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/3210/. This includes a Spatial Microsimulation R-Library by Dimitris Kavroudakis (University of the Aegean) including R code. Available from: www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.268326!/file/sms_Manual_v9.zip.

■ An introductory text to spatial microsimulation: Ballas, D., Rossiter, D., Thomas, B., Clarke, G., & Dorling, D. (2005) Geography Matters: Simulating the Local Impacts of National Social Policies, Joseph Roundtree Foundation. Available from: www.jrf.org.uk/file/36059/download?token=NkTWwksy&filetype=full-report.

Ballas, D., Clarke, G. P., & Dewhurst, J. (2006) Modelling the socio-economic impacts of major job loss or gain at the local level: a spatial microsimulation framework. Spatial Economic Analysis, 1(1), 127–146.

Ballas, D., Kingston, R., Stillwell, J., & Jin, J. (2007) Building a spatial microsimulation-based planning support system for local policy making. Environment and Planning A, 39(10), 2482–2499.

Hermes, K., & Poulsen, M. (2012) A review of current methods to generate synthetic spatial microdata using reweighting and future directions. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 36, 281–290.

Tanton, R., & Edwards, K. (2013) Spatial Microsimulation: A Reference Guide for Users, Springer, Berlin.

BHPS Individual Questionnaire

Core |

Neighbourhood and individual: Demographics Birthplace, residence Satisfaction with home/neighbourhood Reasons for moving Ethnicity Educational background and attainments Recent education/training Partisan support Changes in marital status Citizenship |

Current employment: Employment status Not working/seeking work Self-employed Sector private/public SIC/SOC/ISCO Nature of business/duties Workplace/size of firm Travelling time Means of travel Length of tenure Hours worked/overtime Union membership Prospects/training/ambitions Superannuation/pensions Attitudes to work/incentives Wages/salary/deductions Childcare provisions Job search activity Career opportunities Bonuses Performance related pay |

Finances: Incomes from: Benefits/allowances/pensions/rents/savings/ Interest/dividends Pension plans Savings and investments Material well-being Consumer confidence Internal transfers External transfers Personal spending Roles of partners/spouses Domestic work/childcare/bills/everyday spending Car ownership/use/value of car Interview characteristics Windfalls |

Rotating core |

Health and caring: Personal health condition Employment constraints Visits to doctor Hospital/clinic use Use of health/welfare services Social services Specialists Check-ups/tests/screening Smoking Caring for relatives/others Time spent caring for others Private medical insurance Activities in daily living |

Employment history: Past year Labour force status spells Size/sector/nature of business/duties Wages/salary/deductions Reasons for leaving/taking jobs |

Values and opinions: Partisanship/interest in politics Religious involvement Parental questionnaire |

Variable components |

Lifetime marital status history (Wave 2): Number of marriages Marriage dates Divorce/widowhood/ Separation dates Cohabitation before marriage Lifetime marital status history (Wave 3): Start and finish dates Labour force status Sector/nature of business duties Health and caring: Children’s health Other health scales: SF36 (Wave 9) Computers and computing (Wave 6/7): Ownership and usage |

Lifetime fertility and adoption history (Wave 2 and Wave 8 catch-up): Birth dates Adoption dates Sex of children Leaving or mortality dates Lifetime cohabitation history (Wave 2 and Wave 8 catch-up): Start and finish dates Number of partners Neighbourhood and demographics: Driving licence Parents’ employment background Family background Difficulties with debt Community and neighbourhood Employment (Wave 9): National Minimum Wage Work strain Work orientation |

Lifetime employment status history (Wave 2): Start and finish dates Employment status Values and opinions: Aspirations for children Important events Quality of life Credit and debt: Investment and savings Commitments Crime: Criminal activity on local area Perceptions of crime |

BHPS Household Questionnaire: core questions

Size and condition of dwelling Ownership status Length of tenure Previous ownership Interview characteristics |

Household Finances: Rent and mortgage, loan and HP details Local Authority service charges Allowances/rebates Difficulties with rent/mortgage payments Household composition Consumer durables, cars, telephones, food Heating/fuel types, costs, payment methods Non-monetary poverty indicators Crime |

Appendix 6.3 A selection of policies that were evaluated in SimBritain

Working Families’ Tax Credit