13 |

The importance of mood and relationships in anxiety |

We hope that by the time you come to this section of the book you will have worked your way through the chapters that are relevant to your particular anxiety problem. It may be, however, that you still have some remaining difficulties, or that your progress in overcoming your anxiety has been hampered by problems such as low mood or problems in relationships.

If you suffer from an anxiety disorder then it is highly likely that you will also experience periods of low mood, or even depression. It may be that having the anxiety problem is making your mood low, or that having low mood is making the anxiety problem worse.

When we talk about low mood we mean a whole range of symptoms, including those listed below. These are not the only symptoms of low mood that can accompany anxiety, but they are some of the common ones. For a more complete description of symptoms of depression, see Table 13.1 on p. 406:

• You are likely to have a sense of feeling rather flat and lacking in motivation. It might seem as though normal activities are just too much.

• Feelings of hopelessness. You might find that you feel demoralized, and think there’s no point trying, because nothing’s going to work.

• You might find that you have very little energy, get tired easily, or suffer disruption to your sleeping pattern.

• You might find that you think about yourself in a negative way and feel worthless and useless.

If you have been feeling anxious for a while you can easily lose confidence in yourself. If your anxiety leads you to feel that you can’t do the activities that you used to be able to do, or that life is generally more difficult, then you may well start to think, ‘What’s the matter with me? I’m so useless now; I can’t do anything.’ Thinking that you are useless or a failure can seriously affect your self-esteem, and lead to low mood or depression.

Furthermore, it is tiring being anxious all the time and being tired and worn down can drag your mood down, too. This means that you will have less energy to tackle your difficulties, and are therefore more likely to feel hopeless and demoralized.

Finally, we have seen that it is common for people to avoid certain situations when they feel anxious, resulting in an ever more narrow, restricted life. Not only does this affect your confidence, but you are probably not doing as many enjoyable activities as in the past. We know that when people do not have activities in their life that are enjoyable and rewarding for them, their mood suffers and they start to feel low.

Once your mood has started to get low, it can also make the anxiety itself worse. This happens for a number of reasons. Firstly, low mood can affect you so that you end up not eating or sleeping properly, and tiredness will also exacerbate your anxiety. Secondly, feeling ‘flat’ or ‘sad’ can make it harder to think rationally, and cause you to think negatively about yourself. This impacts on confidence and your beliefs about your ability to overcome your anxiety problems. Thirdly, low mood impedes memory and concentration so that it becomes harder to undertake everyday tasks, even if you want to do them, and harder to remember what you have managed to accomplish. Fourthly, low mood makes you less likely to enjoy social activities and events, so naturally you stay in more. Ultimately this will make going out again even more of a challenge.

In effect, the relationship between low mood and anxiety can act like another vicious cycle. Like other vicious cycles, the good news is that this can become a virtuous one, too!

Figure 13.1: The anxiety–low mood vicious cycle

If your low mood has become very bad, you should consider whether you may be depressed.

Table 13.1 below gives the symptoms of depression adapted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). As we said in Part 1, only a trained mental-health professional can diagnose you as having a particular mental-health disorder. However, the list of symptoms of depression in the table may help you assess yourself.

Table 13.1: Symptoms of depression (based on the DSM-IV criteria)

If you are depressed you will have either 1 or 2 (or both):

1. Your mood has been depressed most of the day, nearly every day, for example, feeling sad, empty.

2. You have noticed a marked diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day.

If you are depressed you will also have at least three or four of the following:

3. You have lost a significant amount of weight (when not dieting), or you have gained a significant amount of weight.

4. You have had difficulty sleeping or have being sleeping a great deal more than usual nearly every night.

5. Other people have noticed that you have been agitated or slowed down nearly every day.

6. You have been tired and have had no energy nearly every day.

7. You feel worthless or guilty nearly every day.

8. You have noticed that you are having trouble concentrating, or that you are indecisive, nearly every day.

9. You think about death a lot, and may have suicidal thoughts, or suicidal plans.

10. Your symptoms make it difficult for you to function at work and at home, or in your social life or other important areas of life.

11. Your symptoms are not due to the physical effects of a substance such as a recreational drug, a medication, or a general medical condition such as an underactive thyroid.

Sometimes it can be hard to tell the difference between low mood and depression because they are so closely linked. The main differences between the two are:

• The depth and intensity of the mood disturbance in depression is much worse than in a passing, manageable low mood.

• Depression seems to go on without any let-up – people’s mood is low and depressed pretty much all of the time.

• Both low mood and depression make it harder to tackle normal life, but in depression this is more than just a feeling that things are difficult. Depression has a significant effect on people’s ability to function, so that even small things seem impossible to tackle.

If you think that you may be depressed, there are two main ways forward. The first is to try to tackle this using self-help methods. There are several good self-help books for depression, including Overcoming Depression by Paul Gilbert (see p. 439). The second is to talk to your GP and discuss whether antidepressant medication may be helpful, or whether a referral to a therapist might be best.

If your mood is not as bad as in a full depression, then the ‘top tips’ below may be sufficient to help you tackle it:

1. Try to make sure you have something pleasurable to look forward to each day. This may be small (for example, turning on an electric blanket at night, having a bubble bath, watching a good TV programme, or listening to music) but it has to be planned and present every day.

2. Use problem solving to tackle specific problems that are causing your low mood (see Chapter 8 on Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Worry).

3. Make sure you have a structure to your day, for instance, getting up at and going to bed at a reasonable time and eating properly.

4. Do not isolate yourself from your friends and family; try to go out and see if it is actually more pleasant than you predict.

5. If you feel that doing too much is contributing to your low mood, then try to slow down for a couple of days as an experiment and see the consequences.

Sometimes when your mood gets very low you can start to think that there really is no hope and no escape, and that you and other people might be better off if you were not around. If you recognize these thoughts, and fear that you are feeling suicidal, please get help straight away. You can make an appointment with your GP or physician. If it is out of hours, then your local Accident and Emergency Department (A&E) has people who can help. You don’t have to live with these thoughts and feelings on your own. The right assistance for recovery is available. You can find a list of helpful resources in the appendices.

Another common aspect to anxiety is that it can affect your relationships with other people, particularly those who you are close to. Problems in relationships can increase our feelings of anxiety. As with so many other aspects of psychological problems, these difficulties can best be described as a vicious cycle, in this case between anxiety and relationship problems.

Figure 13.2: The anxiety–relationship problems vicious cycle

There are a number of ways in which this vicious cycle can work. Firstly, relationship problems can have a big effect on your anxiety. If you are having difficulties with your partner, or with a child or a parent, and are involved in arguments and tension, then you might well feel anxious. You might be going through a period of upheaval in your life – such as divorce, changing job, moving house, arguing with a family member or forming a new romantic relationship. You might have moved and be finding it hard to make friends and become anxious about whether people will like you. You might have lost someone close to you, and as well as feelings of grief and sorrow, worries about how you are going to cope without them may surface. All of these scenarios can provoke anxiety and anxious ways of thinking and behaving.

Secondly, anxiety itself can have a big impact on relationships. For instance, you might stop going out because you just get too anxious in crowds, or in open or unfamiliar places. This means that you are likely to avoid your friends, who can end up feeling rejected, and may even stop contacting you. You might find that you commit to social activities but make excuses at the last minute, which makes people close to you feel let down. It is common for people who suffer from anxiety to cancel holidays at the last minute, even expensive and well-planned ones, because at the final moment their anxiety about leaving home or getting on a plane is too great. Such behaviour will clearly have a significant impact on your partner. Another way in which anxiety can affect relationships is that you might spend a lot of time asking for reassurance from people close to you, or insisting that they take part in your anxious rituals (particularly true of OCD). Or your partner might feel that you have changed and be uncomfortable or frustrated with this new side of you. All of these eventualities can place a great strain on relationships.

If you have anxiety you might be worried about being rejected or abandoned by other people. You might find it harder to deal with conflict in your close relationships, even ‘normal’ levels of conflict that are part of the manageable interactions of everyday life. Sometimes, people with anxiety are so worried about how other people are behaving towards them that they forget to think about how they are behaving themselves. You might find that you are behaving in ways that make the relationship worse without even realizing it. For instance, you might get angry if you think someone is rejecting you – even if they’re not – but because you are angry, they get angry with you, further straining the relationship.

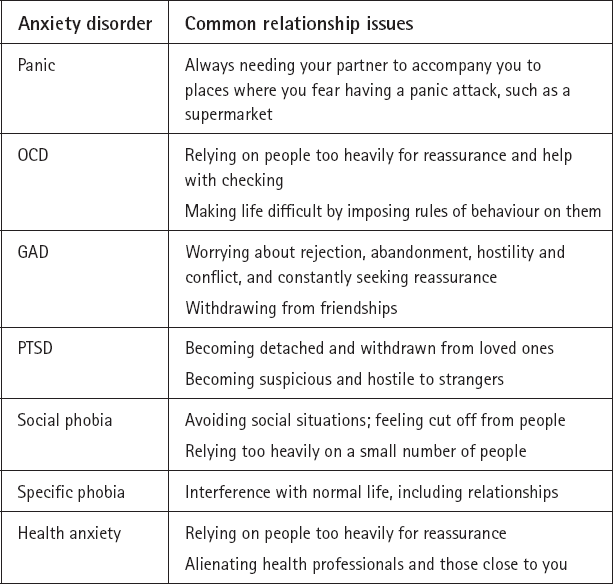

Relationship problems can be present in all types of anxiety. Table 13.2 below shows some of the common issues in relationships that can arise with the different anxiety disorders.

Table 13.2: Anxiety and relationships

There are two particular aspects of relationship problems that we think are especially worth addressing:

We have spoken a great deal about avoidance and the role it plays in anxiety. Avoidance of relationships can increase your sense of isolation. We all need other people. We need people for love and affection, and to feel important and valuable. We also need other people to have fun with! When you avoid situations where you will come into contact with other people, you end up depriving yourself of some very important needs. Your friends will feel rejected if you avoid seeing them, particularly if they don’t know the cause. When you avoid people because you are too anxious to go out, your relationships start to suffer, and you can end up feeling friendless and isolated. This is likely to make your mood lower, and as we have seen this can make your anxiety worse. The bottom line is that we need to find a way to keep relationships and friendships going even when you are most anxious.

Ask yourself: ‘Is my anxiety making me avoid my friends and family? Am I feeling lonely and neglected because my friends and family have given up trying to contact me?’ If the answer to these two questions is yes, then have another look at pp. 62–9 on behavioural experiments to deal with avoidance. Set up an experiment to help you to get back in touch with people and see what happens. Remind yourself that you need people. Even if the prospect of seeing them makes you feel anxious, it really is worthwhile.

There is a typical pattern when we develop problems, whether these are financial, medical, social or anything else. When the problem first occurs, other people usually rally round to help – the crisis brings out the best in people, and they are likely to be kind and sympathetic. If the problem goes on for a long time, people can’t keep the ‘crisis’ level of sympathy going.

They stop being so helpful and sympathetic, and at worst can even seem to be fed up with you, or blame you for how you feel. We sometimes call this change in how people respond ‘compassion fatigue’ – it’s as if your friends and family just get worn out with being sympathetic, so you can end up feeling abandoned and rejected, often when you need help most.

If you have had an anxiety problem for a long time, you and your friends and family are likely to feel fed up. You will probably all feel demoralized and start thinking that you’ll never get better. None of you may know what to do to make things better. People commonly treat those closest to them harshly, so you and your friends and family may be frustrated with each other, and blame each other when things don’t go right. As the diagram of the vicious cycle on p. 408 illustrates, both the relationship and the anxiety can get worse.

It’s important to understand why your friends and family can lose sympathy. It’s common for those around us to become demoralized because their attempts to help us don’t seem to have achieved much. Our loved ones can start to feel useless and powerless when their suggestions and support don’t work. They can feel sad and rejected. If the anxiety has had a big impact on you, and on your joint lives, your partner might feel a strong sense of loss for how you used to be, or how things were between you. Even though it is you who has the anxiety problem, the impact on your close relationships, particularly with your partner, can be pretty serious, too.

One of the first steps to improving relationships is to become aware of whether the vicious cycle is affecting you, and in what way.

Ask yourself, ‘Am I having problems with my friends or my family? Are these problems making my anxiety worse? Or is my anxiety making the problems in my relationships worse?’

Think about the important people in your life. How do you feel when you see them or think about them? Do you feel calmer and more secure? Or do you feel more tense and wound up? Does being with them make your anxiety better or worse? Do you have the same arguments again and again, and repeat the same old lines without either of you listening? Are there issues that repeatedly come up that never seem to be resolved?

If the answer to these questions is that you feel worse around the important people in your life, then you have taken a brave step and you should acknowledge it. It is important to realize that neither of you is deliberately damaging your relationships. It is worth trying:

• Firstly, try to talk to them about what is going on. Getting problems out in the open can be an enormous relief to everyone. Make a deal that you will both try to talk without blaming the other person, and that you will both do your utmost to listen properly and try to understand the other person’s point of view.

• Secondly, try to put nice words and behaviour back into your relationship. Make an agreement that you will both pay each other compliments, even on small daily tasks like cooking, doing the washing up, or on clothes and hair. Try doing something that you know the other person will like – bring them tea in bed, or mow the lawn. When relationships start out people do a lot of these kinds of behaviours, and then forget to do them as time goes by. Even small compliments can help to rekindle the good feelings between you.

• Thirdly, don’t get cross and act rejected (even if you feel it) when your partner or close friend doesn’t respond as you would like. Remember that it is difficult for them, too. You could try letting them know that you understand what it is like for them to live with someone suffering from anxiety.

• Fourthly, try to find a way in which you can be together sometimes where the anxiety problem doesn’t intrude. If you used to like going out to clubs together but you can’t face it now, then hire a karaoke machine and run your own disco at home for the two of you! If you liked going out for meals, then find a quiet pub where you can have a meal together in a corner where no one will intrude. Try to find a ‘calm’ space somewhere in your lives where you can be happy and relaxed together.

If you feel that you need more help than is contained in these simple suggestions, then there are a number of books listed in the Resources section at the end of this book that give you more detail about how to tackle relationship problems. Or you could try going to an organization that helps people with relationship problems, such as Relate – again details are given in the Resources section (see p. 446). You don’t have to be married or heterosexual to go to Relate, and you can even go on your own if your partner won’t come with you.

• Help the person you are supporting to think about their mood and their relationships, and to notice how these are linked to their anxiety.

• Sometimes people might think that low mood and poor relationships are normal and they do not realize that these are problems that can be dealt with. Help them to make a realistic appraisal of the areas of difficulty and see if they would be helped by making positive changes.

• If they have problems in more than one area, help the person to decide which to tackle first, and encourage them to focus on one problem at a time – their anxiety, mood or relationships.