Chapter 9

Swing It! Playing Styles That Rely on the Triplet Feel

In This Chapter

Swinging in swing style

Swinging in swing style

Working the jazz walking bass line

Working the jazz walking bass line

Shuffling through blues style

Shuffling through blues style

Combining styles with the funk shuffle

Combining styles with the funk shuffle

Access the audio tracks and video clips at www.dummies.com/go/bassguitar

Access the audio tracks and video clips at www.dummies.com/go/bassguitar

Tri-pe-let, tri-pe-let, tri-pe-let . . . snap your fingers while you say it out loud, accenting the italicized syllables. Now take a wild guess at what kind of feel (rhythm) this chapter is about. That's right; it's the triplet feel, the feel that all the styles I feature in this chapter are based on. Triplet styles come in two flavors: swing and shuffle.

In music that has a triplet feel, each of the four beats in a measure is broken into three equal parts. Instead of counting “1, 2, 3, 4,” you count “1-trip-let, 2-trip-let, 3-trip-let, 4-trip-let.” You hear four triplets in each measure for a total of 12 hits (occurrences).

Swing: Grooving Up-Tempo with Attitude

Swing style originated in the late 1920s and early ’30s. The style of the Glenn Miller and Benny Goodman bands typifies the music of the early swing era. Bands like The Brian Setzer Orchestra bring swing to today's music scene. In swing style, the first note of the two eighth notes in each beat is slightly longer than the second — long, short, long, short — and it gives the feeling of . . . swinging, of course. Each of the four beats in a measure still has the three parts of a triplet, but you tend to play on only the first and third of each — on the “tri-” and on the “-let” of the “tri-pe-let.”

The bass line in swing style is predictable but cool (it makes you want to snap your fingers). The vast majority of swing tunes are based on a major or a dominant tonality. (I cover tonality in Chapter 5.)

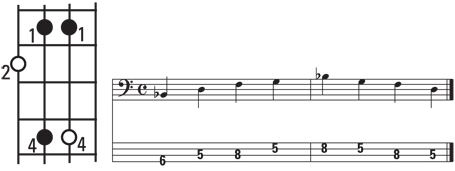

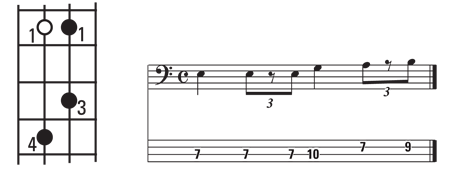

Figure 9-1 shows you a swing groove in a major tonality, using a major pentatonic scale. (See Chapter 7 for an explanation of pentatonic scales.) Start this groove with your middle finger to avoid shifting your left hand.

Figure 9-1: Swing groove using a major pentatonic scale.

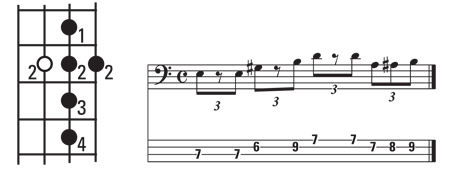

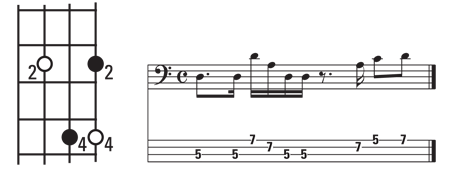

Figure 9-2 shows an example of a swing groove using a mode — in this case, the common Mixolydian mode. (Check out Chapter 5 for information about modes.)

Figure 9-2: Swing groove using a Mixolydian mode.

Jazz: Going for a Walk

A walking bass line simply walks through the appropriate scale of each chord, one note per beat, hitting every beat of each measure. The walking bass line in the jazz style is a more creative form of bass playing than the other swing styles because you choose new notes each time you play the same song. The walking bass line was developed by upright bassists, such as Ray Brown, Milt Hinton, Paul Chambers, and Ron Carter, but these days it's played just as commonly by bass guitarists. The triplet is implied in each beat; just listen to how these master bass players embellish their walk with dead notes (see Chapters 5 and 6 for dead notes).

Creating a walking bass line is one of the more elusive art forms in the bass world, but this section takes you through it step by step (pun intended) so it doesn't seem so obscure. The formula for a successful walking bass line is simple:

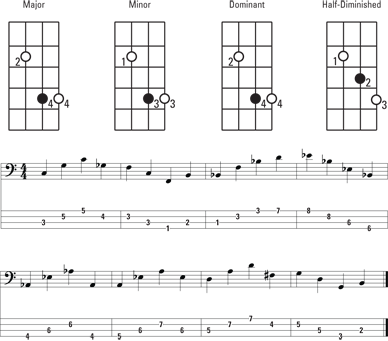

- Beat 1: Determine the chord tonality (major, minor, dominant, or half-diminished) so you know which finger to start with, and play the root of that chord.

In some cases, you may want to use something other than the root of the chord to give the line more melodic variety. If so, you can play a strong chord tone (the 3rd or the 5th of that chord) on beat 1, instead of the root. (See Chapter 5 for more about chord tonalities.)

- Beat 2: Play any chord tone of the chord, or any note in the scale related to that chord.

If you're not sure which scale belongs to which chord, check out Chapter 5.

- Beat 3: Play any chord tone or scale tone of the chord.

Yep — same as Step 2, but pick a different note.

- Beat 4: Play a leading tone to the next root.

A leading tone leads from one chord to the next. The sound of the leading tone isn't related to the current chord; it's related to the chord you're approaching. In other words, the leading tone prepares the listener's ear for the sound of the new chord. The most important point to understand about a leading tone is that it aims for the following chord's root. For example, if you're going from a C chord to an F chord, your leading tone relates to the F (never mind the C).

Leading tones come in three types:

- Chromatic (half-step)

- Diatonic (scale)

- Dominant (the 5 of the new chord)

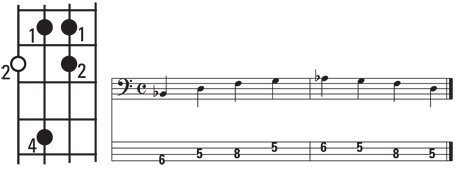

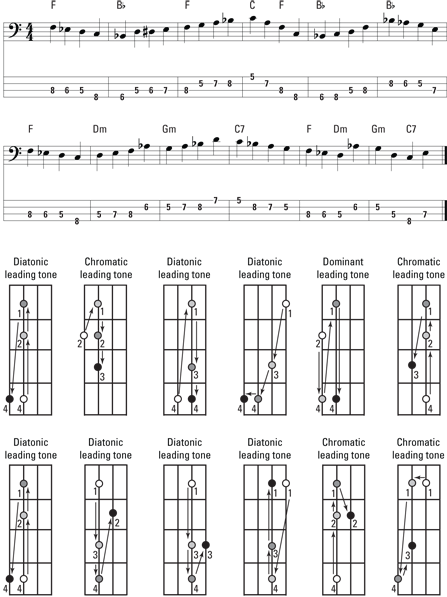

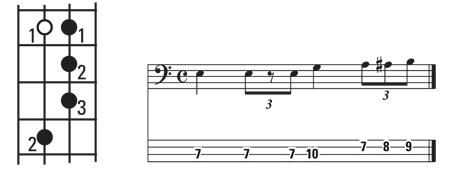

Figure 9-3 shows the location of each type of leading tone. The root of the new chord is represented by the open circle; the leading tones are represented by the solid dots. The arrows show which way the leading tone moves to resolve to the root of the new chord.

In a walking bass line, beat 4 of the measure is reserved for the leading tone.

In a walking bass line, beat 4 of the measure is reserved for the leading tone.

Figure 9-3: The locations of the chromatic, diatonic, and dominant leading tones.

Working the walk

Creating walking bass lines can be overwhelming at first because they don't seem to follow any predictable template the way regular grooves do (check out Chapter 6 for more on creating grooves). However, you can break down walking into three main concepts, and the whole thing becomes as clear as a 5th-fret harmonic on a brand new G string. Here are the three main concepts for walking bass lines:

- Walking using the root, the 5, and a leading tone

- Walking using chord tones and a leading tone

- Walking using scale tones and a leading tone

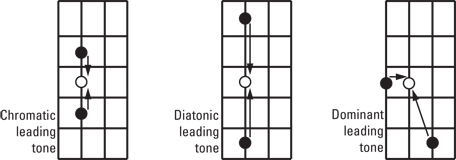

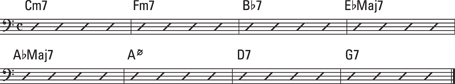

Figure 9-4 shows a typical jazz progression (sequence of chords) that includes the main chord types: major, minor, dominant, and half-diminished.

Figure 9-4: Jazz progression for walking bass.

The root-5 concept

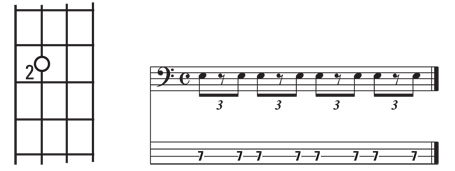

Figure 9-5 is an example of a walking bass line that uses only the root of a chord (including the octave), the 5, and the all-important leading tone that comes on the last beat of each measure (octaves and measures are explained in Chapters 5 and 4, respectively).

Figure 9-5: Walking bass using the root and 5 plus a leading tone.

The most important asset of this method is that you can use the same structure on all the major, minor, and dominant chords in a song. You can move the pattern as a constant structure from chord to chord with ease (see Chapter 6 for information on constant structure). Only the half-diminished chord requires a slight alteration in the pattern — you lower the 5 by a half step (or one fret), making it a diminished 5, which is the defining note for a half-diminished chord.

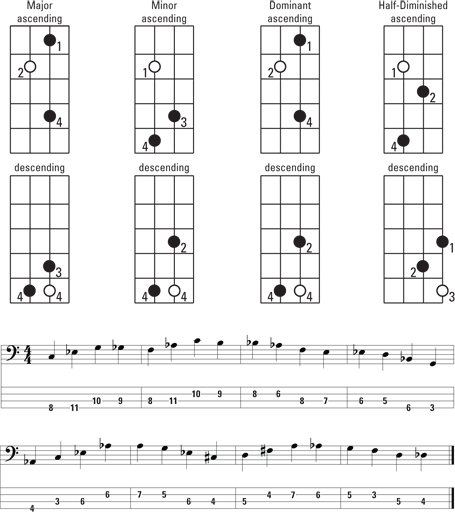

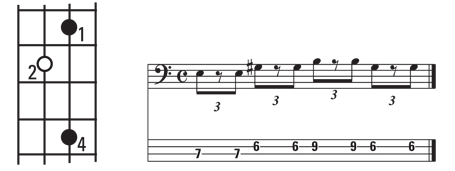

The chord-tone concept

You can bump your bass line to a new level of sophistication when you understand the chord-tone concept. Try playing the etude in Figure 9-6. (Etude is a fancy name for musical exercise.) In this case, you're using the chord tones of each chord, both ascending and descending, plus the crucial leading tone to walk your way from chord to chord through the harmony.

Figure 9-6: Walking bass using chord tones plus a leading tone.

To start, get your fretting hand into the proper position for each chord. Just follow the grid pattern in Figure 9-6 so you can cover all the notes for each chord without shifting. In other words, shift your hand into position at the beginning of each new chord, and then stay there until you have to shift into position for the next chord.

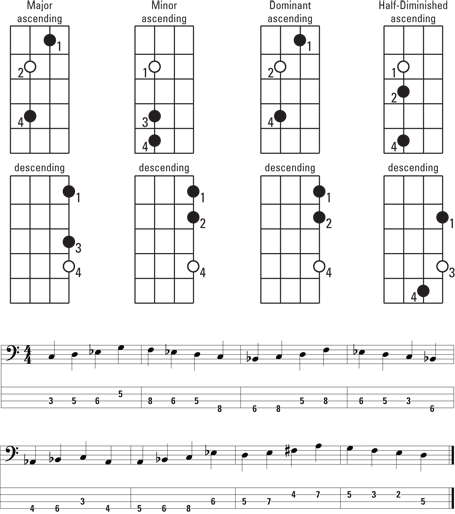

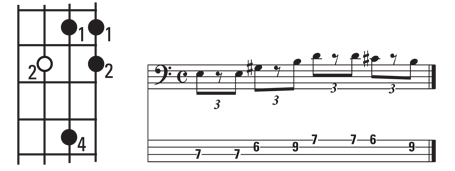

The scale-tone concept

The smoothest and most linear (moving step by step in a scale) walking concept is the one that uses scale tones; you can find an example in Figure 9-7. Play the first three notes of the appropriate scale for each chord, either ascending or descending, and add the leading tone on the last beat of each measure to get smoothly to the next chord (for a thorough explanation of the chord-scale relationships, check out Chapter 5).

Figure 9-7: Walking bass using scale tones plus a leading tone.

Which of the walking concepts in Figures 9-5 through 9-7 is right for you? Well, actually, all of them are great. If you have a good handle on all three concepts, you can switch among them while you're playing your bass part in a song. You'll sound cool, off-the-cuff, and unpredictable. And why not? Walking should be fun to play and interesting to listen to.

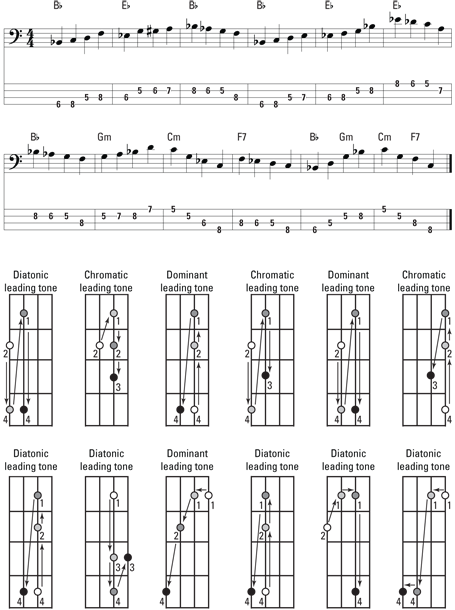

Applying a jazz blues walking pattern

You can walk through almost any jazz tune. To demonstrate the jazz walking style properly, I show you how to walk in a jazz blues progression (see Figures 9-8 and 9-9). In these figures, the chords are printed above each grid. The notes for each measure are clearly marked: Each open circle represents the root that begins the sequence; then you play the light gray circle, followed by the dark gray circle. The leading tone is the last note in each sequence (follow the arrows). You can start this progression on any root. Figure 9-8 is written in B ; you start the pattern on the E string with your middle finger. The pattern in Figure 9-9 is in F, and you start it on the A string with your pinkie.

; you start the pattern on the E string with your middle finger. The pattern in Figure 9-9 is in F, and you start it on the A string with your pinkie.

Figure 9-8: Jazz blues walking pattern starting on the E string.

Figure 9-9: Jazz blues walking pattern starting on the A string.

Which pattern is the right one for which key? Simple. Play the blues in keys G, G /A

/A , A, A

, A, A /B

/B , B, and C, using the pattern that starts on the E string. Play the blues in keys C

, B, and C, using the pattern that starts on the E string. Play the blues in keys C /D

/D , D, D

, D, D /E

/E , E, F, and F

, E, F, and F /G

/G , using the pattern that starts on the A string. In this way, your notes stay in the low register, making your walking bass line more authoritative — and who would argue with authority?

, using the pattern that starts on the A string. In this way, your notes stay in the low register, making your walking bass line more authoritative — and who would argue with authority?

Take your time when starting to play a new tune; you need to figure out the scales for each chord before you play it. The more you play, the faster you become.

Blues Shuffle: Walking Like Donald Duck (Dunn, That Is)

The blues shuffle is one of the most recognizable triplet feels in music. The bass line is an organized walk — it's a walking bass line that's repeated throughout the tune. When you play the blues shuffle, you may feel as if you're playing a lopsided rhythm. The first note is long, the second is short, the third is long, and so on.

Tommy Shannon (bassist for Stevie Ray Vaughan), Roscoe Beck (bassist for Robben Ford), and the incomparable Donald “Duck” Dunn (of the Blues Brothers and Booker T. & the MG's) are three wonderful blues bassists who are superbly skilled at playing the blues shuffle.

Figure 9-10 (at the start of Track 69) demonstrates a blues shuffle groove that uses only one note: The root. You can use this groove for any chord.

Figure 9-10: Blues shuffle groove using only the root.

Figure 9-11 (at 0:11 on Track 69) shows another example of a blues shuffle groove. The 3 and 5 are added to this groove to form a major chord. Start the groove with your middle finger.

Figure 9-11: Blues shuffle groove using a major chord.

In Figure 9-12, (at 0:39 on Track 69) notes from the Mixolydian mode (see Chapter 5 for more about modes) are added to the root, 3, and 5, filling out the chord to form a dominant tonality. Start this groove with your middle finger on the root.

Figure 9-12: Blues shuffle groove using a Mixolydian mode.

But what if the blues tune you're playing is on the sad side, in a minor tonality? (After all, sad tunes are a strong possibility when you're playing the blues.) If you want to play the groove in Figure 9-12 over a minor tonality, you need to make a minor adjustment: Simply change the tonality by flatting the 3 (making it a  3). Figure 9-13 (at 0:59 on Track 69) shows a blues shuffle that includes notes from the minor mode (the Aeolian or Dorian mode).

3). Figure 9-13 (at 0:59 on Track 69) shows a blues shuffle that includes notes from the minor mode (the Aeolian or Dorian mode).

Figure 9-13: Blues shuffle groove using a minor mode.

The blues shuffle groove in Figure 9-14 (at 1:18 on Track 69) is more complex. It includes not only notes from the chord and its related modes (in this case, Mixolydian for the dominant chord) but also chromatic tones (notes moving in half steps; see Chapter 5 for more on chromatic tones).

Figure 9-14: Blues shuffle groove using a Mixolydian mode with a chromatic tone.

Finally, Figure 9-15 (at 1:38 on Track 69) shows a complex blues shuffle, using a chromatic tone, that you play over a minor tonality.

Figure 9-15: Blues shuffle groove in a minor tonality using a chromatic tone.

The grooves in Figures 9-14 and 9-15 use a strong triplet figure (three notes per beat) on the last beat of the measure. This triplet figure helps establish the strong triplet feel for this style. Play around with these grooves and come up with some of your own. By the way, these grooves work well over a blues progression. (See Chapter 8 for the structure of the blues progression.)

Funk Shuffle: Combining Funk, Blues, and Jazz

Funk shuffle (also called shuffle funk) is a hybrid groove style, which means that it combines several elements of other styles — funk, blues, and jazz. When funk, which normally uses straight sixteenth notes, is combined with blues and jazz, which use triplets, the resulting combination is a lopsided sixteenth-note groove (a combination of long and short notes) — a very cool combination. This type of groove is pretty challenging to play, but some useful tricks of the trade can help make it a lot easier.

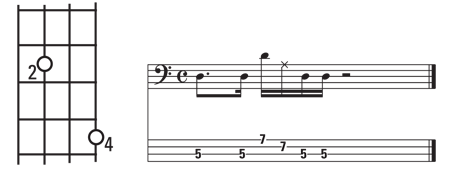

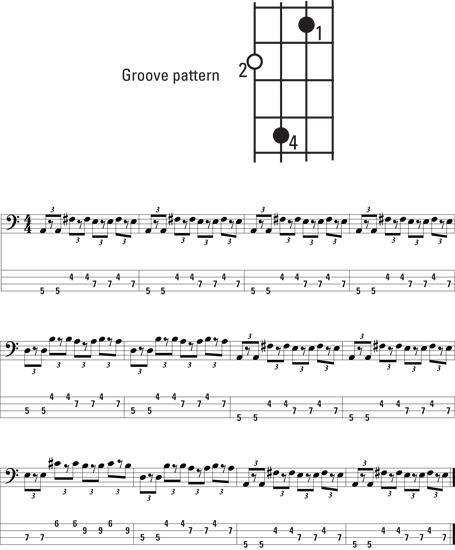

Check out Figure 9-16 (at the start of Track 70) for an example of a funk shuffle groove. This groove uses only the root (in two octaves) with an added dead note (a note that sounds like a thud; see Chapter 5 for a complete explanation). The drums are crucial in this style because they drive the rhythm along in tandem with the bass. You can start this groove with your index or middle finger on the low root (the starting note).

Figure 9-16: Funk shuffle groove using only the root.

Figure 9-17 (0:29 on Track 70) shows an example of a funk shuffle groove that uses notes common to both the Mixolydian (dominant) and Dorian (minor) modes. Whoa! The groove in Figure 9-17 fits over both dominant and minor? Yep! In fact, it's an ambiguous groove (see Chapter 5 for an explanation of ambiguous grooves). This groove isn't all that easy to master, but after you get comfortable with it, you can get lots (and lots) of use out of playing it over any dominant or minor chord. In the funk shuffle style, almost all chords are dominant or minor.

Figure 9-17: Funk shuffle groove for dominant and minor chords.

The funk shuffle in Figure 9-18 (0:58 on Track 70) includes more notes from both the Mixolydian and Dorian modes; notice the cool syncopation — the way a note anticipates the beat that it's normally expected to land on. (Chapter 10 covers syncopation.) The groove in Figure 9-18 can be used over most chords in shuffle funk tunes (that's right; it's an ambiguous groove). Most of the chords are either dominant (Mixolydian) or minor (Dorian). Start the groove with your index or middle finger to keep it in the box (so you don't have to shift your left hand).

Figure 9-18: Funk shuffle groove using notes from the dominant or minor modes.

When you're grooving on a funk shuffle, you can keep going for hours and hours without getting the least bit bored; because of its complexity, a funk shuffle is going to keep you busy. Keep the shuffle funky, “,cause it don't mean a thing if it ain't got that swing.”

The quintessential generic shuffle/swing song is a good old-fashioned blues, like the one in Figure 9-19. (For more on the structure of a typical blues song, check out Chapter 8.)

Figure 9-19: Generic shuffle song.

In this chapter, you can move all the grooves from chord to chord (check out Chapter

In this chapter, you can move all the grooves from chord to chord (check out Chapter  As you listen to the groove from Figure

As you listen to the groove from Figure