Chapter 10

Making It Funky: Playing Hardcore Bass Grooves

In This Chapter

Feelin’ R & B

Feelin’ R & B

Igniting the Motown engine

Igniting the Motown engine

Creating a fusion of styles

Creating a fusion of styles

Playing funk

Playing funk

Hopping to hip-hop

Hopping to hip-hop

Bringing in da funky groove

Bringing in da funky groove

Access the audio tracks and video clips at www.dummies.com/go/bassguitar

Access the audio tracks and video clips at www.dummies.com/go/bassguitar

Gimme da funk! You gotta gimme da funk! When these words echo across the bandstand, they're directed at you (and your alter ego, the drummer). From Motown to hip-hop, the bass player takes a starring role in funk, and your skill and dexterity are put to the test. Funk is essentially party music, and your job is to keep every foot in the room moving to the beat.

Hardcore bass grooves give a real workout for any bass player. In funk, the sixteenth note is the rhythm of choice, and you play quite a few of them. In this chapter, I give you a selection of prime funk grooves that you can use when the words “Gimme da funk!” echo in your direction across the bandstand.

In addition to listening to the audio tracks mentioned in the chapter, you can watch me play many of the grooves in Video 26.

R & B: Movin’ to Rhythm and Blues

R & B (rhythm and blues) originated in the late 1940s and is often referred to as “R & B/Soul.” It's still one of today's most popular styles of music. R & B is dominated by session players — musicians who record with numerous artists. Often, record producers hire the same rhythm section (session players) to accompany all their artists. So you have the same bassist, drummer, guitarist, and keyboardist playing together for years and years on countless sessions with different artists. It's a sure recipe for some serious rhythm section interplay; these cats know each other's playing style.

Tommy Cogbill (who played with such singers as Aretha Franklin, Dusty Springfield, and Wilson Pickett) and Chuck Rainey (who played with Aretha Franklin, Quincy Jones, and Steely Dan) are two great session players. Because of this tradition of using session players, you can hear excellent grooves behind some fabulous singers. These musicians are completely at ease with one another after having recorded a multitude of successful songs together over the years.

The bass groove in R & B consists of a fairly active bass part, locked in tight with the drums. Because R & B music often has such a busy bass line — the harmony includes both scale and chord tones — you need a lot of different notes to keep it interesting and not overly repetitive.

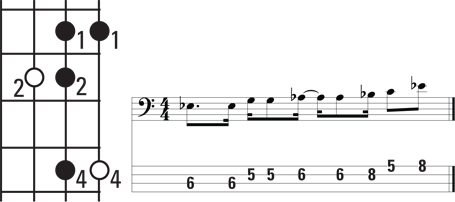

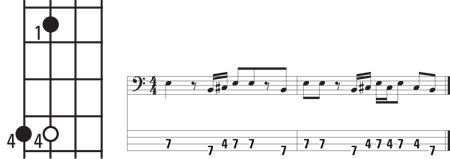

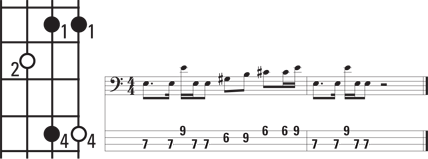

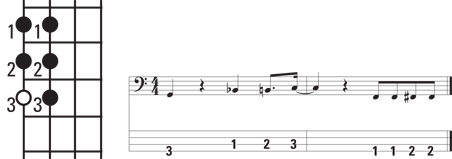

Figure 10-1 (at the start of Track 72) shows an R & B groove in a major tonality. (If you need help creating grooves for different tonalities — major, minor, and dominant — check out Chapter 6.) Start this groove with your middle finger to avoid shifting your left hand.

Figure 10-1: R & B groove using a major (Ionian) mode.

The groove in Figure 10-1 uses notes from the major chord and its related Ionian mode for a major tonality. (See Chapter 5 for information about mode and chord compatibility.) You can also play this groove as a dominant tonality by playing it as is or by using the  7 rather than the 6.

7 rather than the 6.

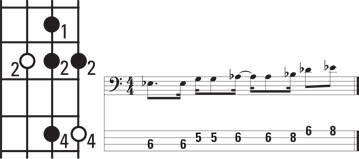

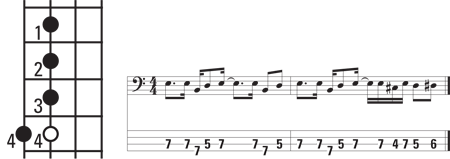

Figure 10-2 (at 0:27 on Track 72) shows an R & B groove in a dominant tonality using the Mixolydian mode. Start this groove with your middle finger to avoid shifting.

Figure 10-2: R & B groove using a dominant (Mixolydian) mode.

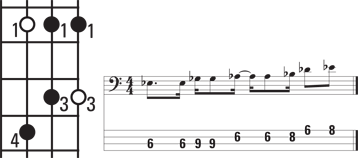

In Figure 10-3 (at 0:53 on Track 72), you can see what the groove from Figure 10-1 looks like in a minor tonality. This groove is based on a Dorian or Aeolian mode (either one will do in this case), and it fits perfectly over a minor chord. Start the groove with your index finger.

Figure 10-3: R & B groove using a minor (Dorian or Aeolian) mode.

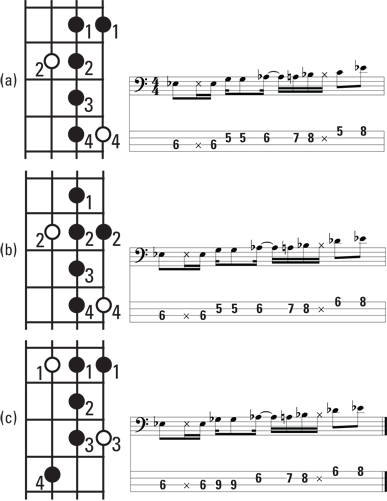

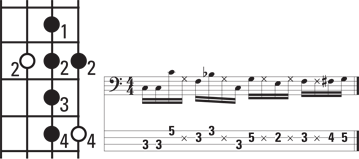

Dead notes and chromatic tones are frequently used in all funk styles, including R & B. (See Chapter 5 for an explanation of dead notes and chromatic tones.) Figure 10-4 shows you what the grooves in Figures 10-1, 10-2, and 10-3 look like with dead notes and chromatic tones added. The grooves in Figure 10-4 tend to sound fairly complex.

Figure 10-4: R & B grooves in major (a), dominant (b), and minor (c) tonalities, using dead notes and chromatic tones.

The Motown Sound: Grooving with the Music of the Funk Brothers

Motown is the name of a record label that got its start in Detroit in the late 1950s. The Motown style is actually part of the R & B family, which you can read about in the preceding section. Numerous singers recorded for Motown, and the vast majority of them were fortunate enough to be able to use the Motown house band — the famous Funk Brothers (a group of top-notch session players) — for their recordings.

James Jamerson (also known as Funk Brother #1) not only defined the label's sound with his active, syncopated lines on hundreds of hits, but he also forged the template for modern electric bass playing. Marvin Gaye, The Temptations, Stevie Wonder, and a slew of other artists benefited from the outstanding groove-creating abilities of Jamerson and the Funk Brothers. Your bass skills also can benefit from the Jamerson/Motown-style grooves featured in this section.

Many of the Motown grooves use constant structure. Constant-structure grooves use notes that occur in more than one tonality. (The shared notes are called common tones; see Chapter 6 for more about constant-structure grooves.) You can play a groove using constant structure over any chord and still make it sound interesting.

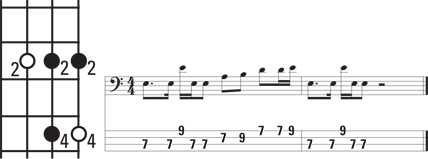

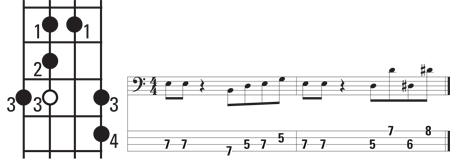

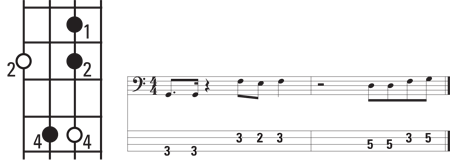

Figure 10-5 (at the start of Track 73) shows a typical Motown groove that works well over a major or dominant tonality. (This one even works for a minor tonality.) When you play the groove, start it with your pinkie.

Figure 10-5: Motown groove using constant structure for major and dominant tonalities.

Figure 10-6 (at 0:22 on Track 73) shows a busy Motown groove using common tones for dominant and minor tonalities. This groove also sports chromatic tones in the second measure (a classic groove tail) that lead back to the beginning of the groove (see Chapter 6 for an explanation of the groove tail). Start the groove with your pinkie.

Figure 10-6: Motown groove using constant structure for dominant and minor tonalities.

Fusion: Blending Two Styles into One

Fusion is the merging of two or more styles of music. Fusion generally refers to the combination of rock rhythms and jazz harmonies, but any combination of styles is possible. Fusion-style bass playing is intricate and complex, and full of nervous energy and fast notes; its deep grooves allow you to really rock the joint. In this section, I show you bass grooves that use every trick in the book: scale tones, dead notes, chromatic tones, and plenty of sixteenth notes.

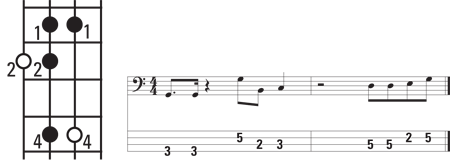

Figure 10-7 shows a busy fusion-style groove that you can play over either a major or dominant chord (Ionian or Mixolydian mode). Notice the use of dead notes and the chromatic tones that make the groove more interesting. Start the groove in Figure 10-7 with your middle finger; no shifts of the left hand are necessary (or desired). The groove is extremely busy, hitting all 16 of the sixteenth notes in the measure.

Figure 10-7: Fusion groove for a major or dominant chord.

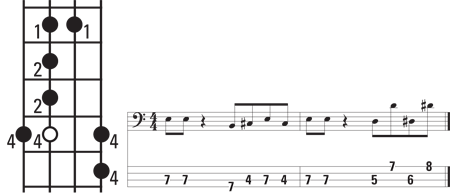

Figure 10-8 (at 0:33 on Track 74) shows a fusion-style groove for a dominant chord (Mixolydian mode). Start this groove with your middle finger.

Figure 10-8: Fusion groove for a dominant chord.

Many fusion-style tunes have an extended section of just one chord. With this type of tune, you don't have to move your groove from chord to chord. You can use a groove that covers all four strings of your bass to really expand your harmonic range. Figure 10-9 (at 1:06 on Track 74) shows such a groove. This groove, which is based on a Mixolydian mode (for a dominant chord), requires no shifting if you start it with your middle finger. It may take a bit of effort to get it under your belt — I mean fingers — but it's well worth it.

Figure 10-9: Fusion groove covering four strings on a dominant chord.

Funk: Light Fingers, Heavy Attitude

Funk is not only a collective term for funk styles; it also refers to a particular style of playing. Funk style is normally percussive in sound and is often played with a thumb (slap) technique (see Chapter 2). But playing finger-style works just as well in producing the percussive sound of funk. Flea (of the Red Hot Chili Peppers) and Victor Wooten (who plays with Béla Fleck and the Flecktones) are two excellent thumbers. Francis Rocco Prestia (of Tower of Power) is a master of finger-style funk. Marcus Miller (a solo artist) is great at using both finger-style and thumb technique.

Funk style emphasizes rhythm. The note choices are often neutral (they work for more than one tonality). Figure 10-10 is an example of a funk groove that's intended to be played by slapping. Of course, when your thumb starts to blister from all that slapping, you can always play the groove using finger-style. This particular groove moves through a little mini-progression (a sequence of chords) that's common in funk.

Figure 10-10: Funk groove played in slap-style.

Figure 10-11 (at the start of Track 76) shows a funk groove that can be played over a dominant or minor chord. It has an aggressive attitude. Start the groove with the index or middle finger of your left hand.

Figure 10-11: Funk groove for a dominant or minor tonality.

Figure 10-12 (at 0:27 on Track 76) shows a funk groove that can be played over a major tonality. (It also works over a dominant tonality.) This groove represents a happy-sounding funk. This happy sound isn't common, but sometimes the happy funk tunes have a way of sneaking up on you, so be ready. After all, where do you think the term slap-happy came from?

Figure 10-12: Funk groove using a major tonality.

The groove in Figure 10-13 (at 0:57 on Track 76) is a heavier funk groove in a minor tonality with a couple of chromatic tones added. (Remember: The more notes in a funk groove, the lighter the groove; the fewer notes in the groove, the heavier the groove.) Start this one with your pinkie or ring finger to keep the shifts to a minimum.

Figure 10-13: Heavy funk groove using a minor tonality.

Figure 10-14 (at 1:26 on Track 76) shows a heavy funk groove in a major or dominant tonality. While the major tonality isn't commonly found in funk, it's a good idea to be prepared in case you encounter one. Instead of defining this groove as a blatant major by adding a 3, you can avoid the 3 altogether by substituting the 6 (a neutral note). Start this groove with your pinkie to keep the shifts to a minimum.

Figure 10-14: Heavy funk groove for a major or dominant tonality.

In Figure 10-15 (at 1:55 on Track 76), you have a funk groove that fits over both minor and dominant chords and is played in finger-style. (I suggest using finger-style when you have a lot of fast-moving notes in a groove.) Start this groove with your pinkie or ring finger.

Figure 10-15: Finger-style funk for a minor or dominant tonality.

Figure 10-16 (at 2:21 on Track 76) shows you a finger-style funk groove in a major tonality (the counterpart of the groove from Figure 10-15). Start it with your pinkie.

Figure 10-16: Finger-style funk groove using a major tonality.

No matter how you play the grooves in this section, make them funky. Practice them with a metronome (see Chapter 4) and make them precise — and above all, enjoy!

Hip-Hop: Featuring Heavy Funk with Heavy Attitude

Hip-hop entered the music world in the 1990s. This style features a fat (“phat”) bass groove that sounds more laid-back than some of the other funk styles. Hip-hop is all about the message; the bass groove provides an important but unobtrusive accompaniment to the vocals. Although the bass line isn't busy, it's well timed and repetitive. The feel and attitude are the most important features of the hip-hop groove. Raphael Saadiq is a well-known hip-hop bassist; he's best known for his work with D'Angelo and Tony Toni Tone.

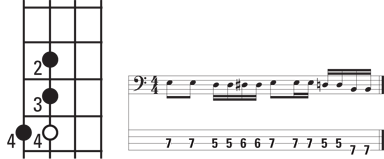

Figure 10-17 (at the start of Track 77) shows a hip-hop-style bass groove. Start the groove with your ring finger.

Figure 10-17: Hip-hop groove.

The tonality in hip-hop is often minor, but it may occasionally be a dominant tonality. Notice that the groove doesn't move much from its starting chord. The tone is usually much darker than the bright funk style.

Figure 10-18 (at 0:26 on Track 77) shows another groove in hip-hop style, this one for a minor or dominant tonality. Start this groove with your middle finger.

Figure 10-18: Hip-hop groove for a minor or dominant tonality.

Figure 10-19 (at 0:52 on Track 77) features a groove for a major or dominant tonality; it's for the happy hip-hoppers. Start this groove with your middle finger.

Figure 10-19: Hip-hop groove for a major or dominant tonality.

A synthesizer is sometimes used to play (or even double) the bass groove in hip-hop, but nothing grooves like the real thing.

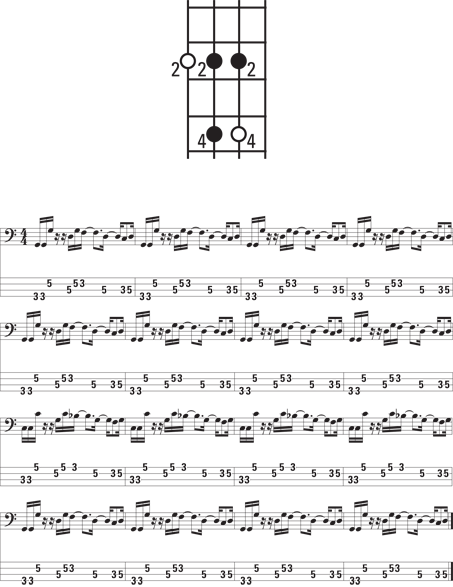

Knowing What to Do When You Just Want to Funkifize a Tune

You wanna bring in da funk? But how? That's a loaded question. You need a groove that does the funk genre justice and at the same time is ambiguous enough to fit over just about any chord. Voilá! I present to you the slam-dunk-funk-R-&-B/Soul-always-makes-people-happy groove that gets the job done. When you're in a pinch and don't know what to play on a song, whip out the hip little groove in Figure 10-20 to hold down the bottom. Chances are you'll be right on the money with it.

Figure 10-20: Generic funk groove and song.

The use of syncopation — a tied note that anticipates a beat (for more on ties, check out Chapter

The use of syncopation — a tied note that anticipates a beat (for more on ties, check out Chapter  You have to listen carefully to hear the subtle difference between the major and dominant grooves shown in Figures

You have to listen carefully to hear the subtle difference between the major and dominant grooves shown in Figures  To keep your R & B grooves interesting, you may want to start with simple rhythms and notes, and then you can add dead notes and chromatic tones as you get deeper into the tune.

To keep your R & B grooves interesting, you may want to start with simple rhythms and notes, and then you can add dead notes and chromatic tones as you get deeper into the tune.