The next pages contain an illustrated roundup of some kitchen equipment we find useful, so that you will see it all in one place rather than scattered throughout the two volumes.

Some of these implements are standard American, others are professional American, still others can be found in import shops or mail-order catalogues, and some are things to look out for if you go abroad and are browsing around in restaurants or butcher supply houses near the central markets. As always, we advise you to look for solid, practical, professional equipment designed by people in the chef business who sell to chefs. If you have trouble locating good equipment in your area, ask your butcher or the owner and chef of the best restaurant in town.

For browning meats and vegetables and for general sautéing, the heavyduty professional frying pan with its long handle and sloping 2-inch sides is the best shape. American cast-aluminum models (A and D) come either with plain or no-stick interiors. The French poêle (B) is of tôle épaisse (very thick sheet metal); one with a bottom diameter of 7 to 7½ inches is ideal for omelettes. The oval cast-iron pan (E), poêle à poissons, is as useful for browning roasts as it is for sautéing fish. The short-handled cast-iron American skillet (C) is also good in the oven, and is the pan to use for pommes Anna; the same shape can be found with an enameled surface, making it ideal for cooking in white wine, or for storing and serving stews or sautés.

You should have at least three sizes of frying pans—a large one 11 inches across its top diameter, a medium, or 10-inch, pan, and a smaller, 7- to 8-inch, pan for single servings and crêpes. You will probably end up with many more, some of one material, some of another, and each your pet for certain techniques.

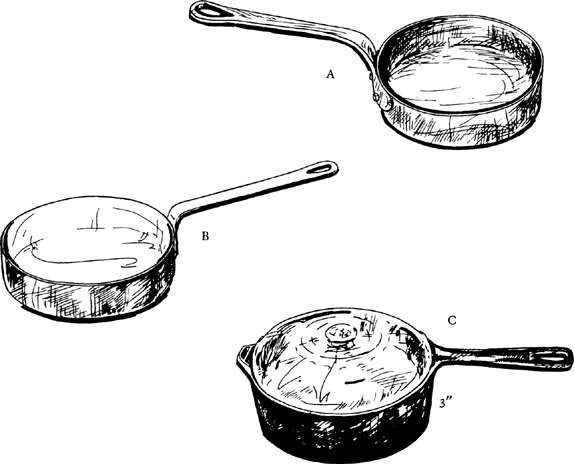

CHICKEN FRYERS

The straight-sided frying pan known as a sautoir in French and as a chicken fryer here, is useful, of course, for fried chicken, but it is also good for chicken sautés and fricassees, beef stews, fish stews, and numerous vegetable dishes. Because the cooking usually takes place on top of the stove, it must be of heavy material. The traditional shape (A and B) is typical of the French copper sautoir and of the American professional cast aluminum; the sides are 2¼ to 2½ inches high. The deep chicken fryer (C) is of cast iron; this is a fine cooking utensil, but remove foods from it as soon as they are done to prevent discoloration.

SAUCEPANS, KETTLES, COVERS, AND COLANDERS

You will need saucepans (casseroles) for sauces and saucepans for general boiling and simmering. When you are cooking with white wine or egg yolks, use a non-staining material like lined copper, stainless steel, flameproof ceramic or glass, or the familiar French enameled cast iron with wooden handle (A).

For boiling potatoes, pasta, and their like, cast aluminum is fine although you will have to scour it from time to time. The professional shape (B-1) is well designed; 1½, 2½, 4½, and 7 quarts (B-2) will give you a reasonable range of pan sizes.

Rather than having a special cover for each pot, a series of long-handled covers allows one to fit several sizes of saucepans (C).

Soup kettles (marmites) are essential for pot-au-feu, soups, bouillabaisse, lobsters, green beans à la française, and spinach. An 8-quart kettle and another of 18- to 24-quart capacity would meet most of your needs.

One of them might be the two-handled type (E or F), and another the preserving-kettle type with bucket handle (H). A French earthenware marmite (G) is attractive for soups and stews that are cooked and served in the same pot.

A large sturdy colander is a must; buy one 10 to 11 inches across the top diameter and 5 to 6 inches high, with feet (D).

Casseroles (cocottes) can double as saucepans or roasters, and are essential for stews and braises. Enameled ironware is always good because it will go on the stove or into the oven (A, B, C) and foods will not discolor in it; the oval shape is the best if you are limited in space or budget. The American heavy cast-aluminum (H) comes with a removable rack, and in several sizes up to the large turkey roaster. The French daubière (G) is in lined copper. Earthenware casseroles (D, E, F) are wonderful for cooking and serving because they spread and retain heat. The attractive copper cocotte (I) was designed for the famous potato dish pommes Anna, but may be used as a casserole or as two separate baking dishes.

WARNING: All casseroles, baking dishes, plates, pitchers, cups, and other utensils of earthenware, terra cotta, and like materials must be of the high-fired so-called stoneware type, or must otherwise by clearly labeled and certified safe for the cooking and serving of foods and drinks.

GRATIN DISHES AND ROASTING PANS

Flameproof dishes about 2 inches deep are used for baking, gratinéeing, roasting, and serving, and you should have a reasonable number of sizes. Enameled iron gratin dishes (plats à gratin) (A and E) are either oval or round, and come from shirred-egg size up to 13 to 14 inches long and 9 inches wide. Earthenware gratin dishes (B) are always attractive for serving. A nest of aluminum dishes (F) is conveniently stored and long lasting. Rectangular enameled iron (C) can be plain or with no-stick interior, and will double for roasting or gratinéeing. Be sure to have a rack (G) that will fit into your large roasting pan so that legs of lamb can be raised out of their juices. If your oven does not come with a perforated rack for the broiling pan (D), buy one separately; otherwise spluttering fat can catch fire while you are doing a steak.

IMPLEMENTS—KNIVES

Very sharp knives are the mark of the serious cook, and continual use of the butcher’s steel will keep them razor sharp. Carbon steel knives are preferred by most chefs, but there are stainless knives that will sharpen easily too.

The Central Hoard

The straight-edged, wedge-shaped cook’s knife (C,D,E,F,G,H) is the all-purpose shape for chopping, slicing, paring, and general cutting; you will need at least three, from the 2- to 3-inch blade for paring and small minces to the 10- to 12-inch blade for chopping and rapid slicing. Curved blades (A and B) are good for paring. A professional butcher’s steel (J) with blade 10 to 12 inches long is the best sharpening equipment. A larding needle (I) is indispensable for larding meat.

Slicing, carving, and boning knives have curved blades. Here is the slicing scimitar (K), and two other slicing shapes (L and M). The stubby knife (P) and its longer companion (O) are boning knives, as is the very thin knife known as a chicken sticker (Q) with its short blade; the longer-bladed version (N) is a Norwegian herring filleter, which is also useful for slicing off pork rinds and for cutting thin sheets out of pork fat.

Serrated Sawers

Serrated knives include the curved grapefruit knife (A), the bread knife (B), the all-purpose slicer (C), the frozen-food cutter (D), the ham slicer, which also does smoked salmon (E), and the vicious-looking French meat slicer (F), which is, in addition, very good with slab bacon.

Choppers and Rockers

The traditional chef’s knives (J and K) are for general chopping, as illustrated in Volume I, page 27. The Japanese version (I) works equally well. The two rockers (G and H) are marvelous for mushrooms and parsley, particularly the 3-bladed professional model.

BASHERS, BLUDGEONS, AND BLUNT INSTRUMENTS

For whacking up turkey carcasses, chopping bones, and flattening cutlets, here is a choice of weapons. The meat tenderizer with its cast-aluminum head has waffled sides for tenderizing (A) and smooth sides for flattening cutlets; you can also use it as a hammer, although the rubber-headed hammer that you can buy at any good hardware store (F) is less noisy. The French cleaver, feuille à fendre (D), or an ordinary hatchet (E) are for whacking carcasses or bones, and a hammer helps. The French cleaver-tenderizer, batte à côtelettes (B), is a useful instrument, and the wooden British basher (C) is for flattening cutlets that are held between sheets of waxed paper.

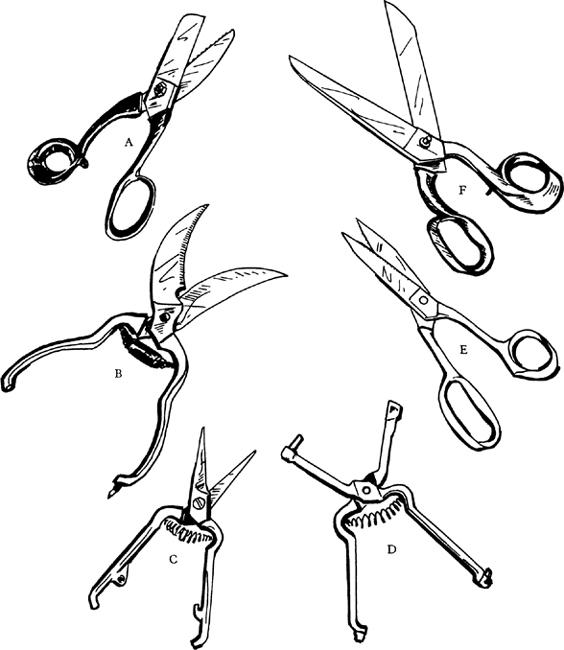

Heavy shears for cutting fish fins, gristle, and rib cages are the serrated French pair (A) and the heavy utility model (F), also French. Poultry shears with their curved blades (B) are useful on occasion, as are the sharp-pointed lobster shears (C). General purpose stainless kitchen scissors with take-apart blades (E) can go into the dishwasher. The scissor-action cherry or olive pitter (D) is invaluable when you have those jobs to do.

You can rarely have enough spoons, and all sizes are needed. Large models of tough nonmetallic composition (A and B) are essential for stirring in no-stick pans. Large stainless-steel spoons (E and F) have hundreds of uses, as do those of serving-spoon and soup-spoon size (C and D). The sturdy icecream spoon (H) does its job well, as does the no-stick scoop (G).

For testing meat and artichokes, for lifting, carving, and spearing, you need a number of sharp-pronged forks like the large chef’s model (I) for enormous roasts and giant birds, and general-purpose forks (E and G), as well as something like the slender Danish three-pronged pickle fork (D). The mixing fork (H) with its six flat-bladed prongs is a great American invention for blending and mashing. A wooden fork (F) is useful for stirring braised rice, and a salad fork (C), combined with spoon, does many a neat job of tossing. The table fork (B) is constantly on call for beating eggs, pricking pastry, general lifting, and stirring, while the small two-pronged fork (A) comes in for pokings and turnings.

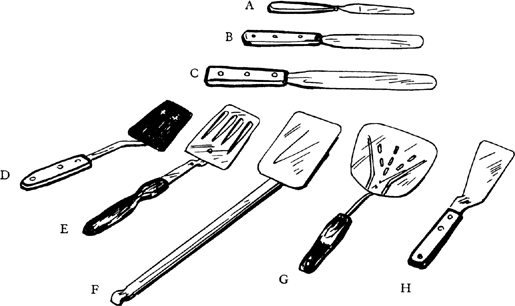

Flexible-blade spatulas scrape fragile cookies off of baking sheets, spread icings over cakes, and slide quiches onto plates; the 12-inch blade (C) and 8-inch (B) are useful sizes. The palette knife (A) is marvelous for delicate liftings and spreadings. Pancake turners of nonmetallic composition (D) are essential when you cook in no-stick pans, and stainless all-purpose models (E,F,H) are standard equipment. The very wide turner (G) does many a lifting job, such as getting asparagus out of hot water.

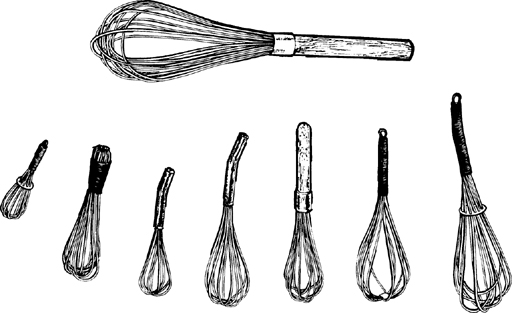

Wire whips or whisks which come in a variety of sizes from minute to gigantic—are wonderful for beating and general mixing.

Metal tongs (A and C) are for lifting and turning meats on a barbeque or in a pan, as well as for retrieving items from boiling oil. The Japanese wooden tongs (B) do many chores and are especially great for turning bacon in the pan. Life would be hard without the perforated spoon (E), and it is easy to become addicted to the great Italian scoop (D).

WOODEN SPOONS, SPATULAS, AND CHOPSTICKS

Why stir it with a wooden spoon? Because it blends the flour and butter roux without racket, and it scrapes the coagulated roasting juices into the deglazing sauce with more quiet efficiency than metal against metal. Actually, the French bowl-less wooden spatula (I,G,F), or the Japanese wooden spatula (H), or the no-stick spatula implements (C and D) are far more useful for every stirring, scraping, mixing, and beating job than the wooden spoon (A and B). Do not forget wooden chopsticks (E); they will beat the eggs for the omelette, lift the green bean out of the boiling pot for testing, and turn the bacon.

Opening, prying, and poking operations will be easier on fingers and tempers when you have something like A or C for screw-topped jars, or the all-purpose-everything item, B. The French tool, G, is for cans and general prying, while the box-opener-hammer-hatchet-etc. instrument, D, is useful anywhere. Ice picks, both the single-pointed F, and the 5-pronged E, are multi-purpose musts. Citrus zesters H and J are good for bar as well as kitchen, and the potato ballers I and K are useful for fruits and vegetables alike.

For grating, puréeing, and grinding, some hand-operated gadgets do a better job than the electric blender or mixer. Use 4-sided grater, L, when you want to grate orange rind or you need coarsely grated Swiss cheese, or a few slices of carrot; look for one in stainless steel. When grated cheese is to be spread over the sauce Mornay, hold the little French rotary grater, M, right over the gratin dish. The table model, N, is for great mounds of cheese if you do not have a grating attachment for your electric mixer.

Again, in spite of the marvels of the electric blender, you do need an efficient food mill for applesauce, puréeing soups, turnips, artichoke hearts, and canned Italian plum tomatoes. The French model, O, with removable disks and folding rubber-padded feet is still the best, in our opinion. One with a top diameter of 9 inches is the standard size; if you are having more than one, the 7-inch size is handy for small jobs like sieving hard-boiled egg yolks.

The old-fashioned potato masher, P, is not to be ignored, nor is the rectangular-headed garlic press, Q. Beware of faulty designs, however, especially in garlic presses. These should take a quite large, whole, unpeeled clove of garlic; the point is that you do not have to peel the garlic. The rectangular head allows a reasonably large clove to be puréed, and the holes should be just the right diameter for the press to do its work easily; if the one you buy does not perform as you think it should, take it back and demand a refund. Get yourself a good peppermill for the kitchen; the French Peugeot models (R and R-1), are always reliable.

Public performances are long when the flame lies low; chafing-dish heat elements are for cooking, and must provide proper heat. Unless you want the efficient gas-operated model, T, look for the kind that will hold a whole can of solidified alcohol, S, and that has an opening which will give you a large heat source.

The French salad basket, U, also comes with a rotary ratchet-gadget that spins salad greens dry in a jiffy. The basket for the Swiss model, V-1, fits into a container, V-2, which catches all the splattering water as the lettuce leaves whirl inside it.

If you do not have a meat-grinder attachment for your electric mixer, buy yourself a sturdy table model, W, always picking the large size for quick and easy operation. Many grinders come with the sausage-stuffing horn you will need for the charcuterie recipes (see illustrations).

From squeezing out cream puffs to making meringue cakes and potato borders, nothing will do the work as easily nor with as professional a look as the pastry bag (A) with its collection of interchangeable metal tubes. Buy the big professional, washable, canvas bags, 12, 14, and 16 inches long; in comparison with your other kitchen equipment, these are inexpensive, and so are the metal tubes. For a start, get 2 or 3 tubes with plain round openings varying from ¼ to ¾ inch in diameter (B), and a cannelated group of the same dimensions (C). Among the latter, the widely spaced teeth (C-1) are for rough masses like potatoes duchesse, while the fine teeth (C-2) are for icings. Ribbon tubes, both plain and cannelated (D), are used particularly for such decorations as the meringues for the Saint-Cyr; one of each, ¾ inch wide, should be sufficient.

BEATING EGG WHITES

You are far more likely to welcome soufflés, meringues, cakes, and baked Alaskas—or even to encourage them—when you have the proper egg-white beating equipment. We urge you to consider the type of heavy-duty electric mixer illustrated here (A). Its large revolving whip (A-1) also rotates around the bowl, beating egg whites so easily it will never again occur to you to think of them as a problem. In fact, this is a replica of the large industrial machines designed by professionals for professionals; to have a home model available is a tremendous help to all of us.

While you are at it, buy an extra bowl and an extra whip, to save you the chore of washing and drying in a single recipe like the Saint-Cyr, which calls for a butter and chocolate mixture as well as for beaten egg whites. The straight-sided bowl, in addition, is just the right shape for raising yeast dough. The dough hook (A-2) works very well for kneading French bread or brioche dough, while the flat beater (A-3) will do the whole operation for a pastry dough from working the butter into the flour to blending in the cold water; when you are doubling or tripling pastry recipes, or blending large batches of sausage meat, the heavy-duty action and ample bowl do the work with ease and speed. The bowl or jack attachment that holds either hot water or ice around the main mixing bowl (A-4) quickly warms the eggs and sugar as you beat them into a foaming mass, or chills the fish quenelle mixture so that you can beat in the maximum amount of cream. The set of rotary graters, slicers, and shredders (A-5) makes fast work of lots of cheese to grate, potatoes or onions to slice, or even mushroom duxelles. The food processor has made many of these attachments obsolete, but they still have their uses, especially when you are doing large quantities.

Whether you beat egg whites by machine or by hand, the theory and practice are the same. Have them at room temperature: they tend to coagulate and fleck when chilled. Start beating rather slowly until they begin to foam, add a pinch of salt and, if you are not using unlined copper, a scant ¼ teaspoon of cream of tartar for each 4 egg whites. Gradually speed the beating action to fast as you circulate the beater all around the bowl, keeping the whole mass in motion, and beating in as much air as possible to increase the volume of the egg whites by sevenfold at least, and until they form the peak illustrated here (B).

The unlined copper bowl (C) is chic, expensive, and looks pretty hanging by its ring on the kitchen wall; it works marvelously well. Egg whites beaten in it retain their volume and satiny gleam, and no one seems to know why. But a small stainless bowl (D) held in one hand, an electric beater held in the other (E), and cream of tartar work very well too. The important point for each is the beater-bowl relationship. Use the largest whip that will fit into a copper bowl (F) or the smallest stainless bowl that will function with your hand-held electric beater; in each case, this is so that you can keep the whole egg mass in continuous motion.

Great-grandmother used to calculate how hot her oven was by the time it took to brown a piece of white paper; taffy was done when the sugar syrup formed a hard ball in a glass of water; and if she missed on the roast she claimed she had gotten out of the wrong side of the bed that morning. Meat thermometers take the guess out of roasting; standard types are the stainless model (G) and the dial type (C). The vest-pocket thermometer (E), with its carrying case (D), is used by professional testers, and has a dial that registers from zero to 220 degrees F. (Weston Instruments, Inc., Newark, N.J.). A thermometer for deep-fat frying (A) can double for candy making, but if you do much sugar work you will want a candy thermometer too. Accurate oven thermometers are essential for any serious cooking. The stainless-steel type (B) is to be had in most stores; the professional folding oven thermometer (F) is manufactured by the Moeller Instrument Company, Richmond Hill, N.Y. When you are warned not to let the crème anglaise come near the boil or you may scramble the egg yolks, yet sternly reminded that you still must heat them enough to thicken the sauce, this stainless-steel temperature spoon (H) will tell you when 160 degrees and the danger point have arrived; since its temperature dial registers from 50 to 400 degrees, you can also use the spoon for sugar boiling and deep-fat frying.

Great-grandmother, our sacred example, measured by feel and hearsay. Her recipes called for a piece of butter the size of a walnut or an egg, a fistful of flour, as much milk as would fit into a teacup. Little failures could be blamed on the weather, the wind, or the vagaries of the coal-burning stove. We have no such excuses now, praises be to Fannie Farmer, who pioneered the whole movement away from the rounded soup spoon of unspecified dimensions and the wine glass of infinite capacity; it was she who helped establish the level tablespoon that holds exactly ½ liquid ounce, and the strictly calibrated 8-ounce cup.

Glass measures with pouring lips are basic equipment; have the three sizes that hold 1, 2, and 4 cups, respectively (A,B,C). Dry measures register to capacity when the cups are filled to the brim; these are the only accurate cup measurements for sugar, flour, and salt. The easiest to use are the stainless-steel type with long handles (E,F,G,H); have at least 2 sets so that some will be available while others are being washed. At least 2 sets of measuring spoons (D) are useful too, for the same reasons.

For all flour measurements in this volume, scoop the dry-measure cup directly into the flour sack or flour container, and fill the cup to overflowing (A)—do not shake or pack down the flour; sweep off excess flour even with the lip of the cup, using the straight edge of a knife (B). Then sift the flour, if

your recipe calls for sifting; for many recipes, however, such as pastry dough, the flour need not be sifted at all. Cups and spoons can never measure flour with the accuracy of scales, but this scoop-and-level system has proved itself out to our satisfaction, and is much easier and faster than the sifting-into-cup method we used in the first edition of Volume I. Here is a conversion and equivalency table for measuring different flours, and for changing old Volume I measurements into the scoop-and-level system.

FLOUR MEASURING CHART*

All-purpose and hard-wheat flour measured by the two methods

Cake flour, soft-wheat flour, French flour measured by the two methods

PANS

|

ROUND CAKE PANS (A) 4-cup size, 8 inches (top) diameter, 1½ inches deep 6-cup size, 9 by 1½ inches FRENCH PANS—moules à biscuits, moule à manqué 6-cup size, 8½ inches (top) diameter, 1½ inches deep 8-cup size, 9 by 2 inches |

|

SQUARE CAKE PANS (B) 6-cup size, 8 by 8 inches (top), 2 inches deep 8-cup size, 9 by 1½ inches 10-cup size, 9 by 2 inches FRENCH PANS—moule à manqué carré 5-cup size, 7¾ by 7¾ inches (top), 1½ inches deep 7-cup size, 9 by 1½ inches |

|

PIZZA PANS—ROUND COOKIE PANS (C) 12 to 14 inches inside diameter and ¾ inch deep FRENCH PAN—tourtière, various sizes usually in black iron, tôle noire |

JELLY-ROLL PAN—BAKING PAN (D) 15½ by 1½ inches (top), 1 inch deep FRENCH PAN—caisse à biscuits, caisse à génoise, many sizes from 8 by 12 inches up to bakery dimensions |

|

COOKIE SHEETS—BAKING SHEETS (E) 9 by 14 inches to 14 by 17 inches for home ovens FRENCH BAKING SHEETS—plaques à pâtisserie, plaques à bords évasés, plaques à pinces—in tôle noire or in aluminum, various sizes from 12 to 14 inches on up |

|

4-cup size, 8 inches (top) diameter, 1¼ inches deep 5-cup size, 9 by 1½ inches 6-cup size, 11 by 1¼ inches FRENCH PAN—no equivalent |

|

BREAD PAN—MEAT-LOAF PAN—ANGEL-LOAF PAN (G) 4-, 6-, and 8-cup sizes, varying widely in measurements according to individual manufacturers. For example, a pan 3½ inches deep, with top dimensions of 10½ by 4 inches and bottom dimensions of 9 by 2½ inches, holds 6 cups. Angel-loaf pans are usually 13 inches long (top) for the 2-quart size, and 16 inches for the large 4½-quart model. FRENCH PANS—moules à cake, moules à biscottes, moules à pain de mie (covered), in a variety of sizes |

PASTRY—ROLLING, SCRAPING, AND GLAZING

If you are going into quiches, pâtés en croûte, and especially into the fascinating realm of French puff pastry, get yourself a slab of marble 2 feet square and ¾ to 1 inch thick; its coolness helps prevent the dough from softening, and its smooth surface is easy to scrape clean.

One or two professionally designed rolling pins with rolling surfaces 16 to 18 inches long are essential for any pastry work—the silly toy pin (A), still sold to debutante cooks, makes hard work of any rolling operation. The French boxwood pin, rouleau à pâtisserie en buis (B) or its Italian equivalent, both without handles, are as useful for rolling as they are for beating chilled pastry into rolling shape. The fine professional American ball-bearing pin (C) is heavy enough to do half the work for you, and the cannelated pin (D), le Tutove, is especially designed to spread out the layers of butter inside the croissant dough as you roll. The rotary croissant cutter (E) then finishes the operation.

For scraping pastry off the work surface, and also for cutting and chopping dough, the hardware-store paint scraper (F) does almost as good a job as the French pastry scraper, coupe-pâte (G). The pastry blender (H), with its multiple chopping blades, cuts the butter into the flour when you are making pie dough by hand—it prevents the hot-finger syndrome that causes cardboard pastry.

Several pastry brushes (I) are needed, for glazing the tart with beaten egg as well as for general basting; be sure to buy ones designed for pastry or for basting, since cheap brushes leave bad tastes and drop hairs.

SMALL MOLDS—PETITS MOULES—FOR TARTLETS, BRIOCHES, PETITS FOURS

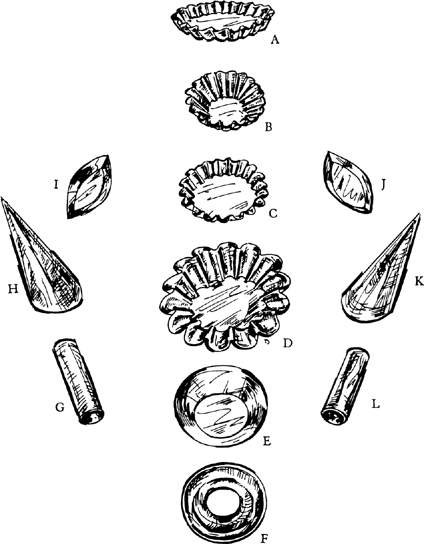

These should be in tinned metal, fer-blanc which is less likely to cause sticking problems than aluminum; if you have to scrub them after baking, warm them briefly and rub lightly with oiled paper toweling to keep the molds from rusting or sticking. Buy at least a dozen of whatever models you chose, so that you can form and bake as many at once as possible. Tartlet molds (A,C,I,J,E) are usually ½ inch deep and from 1½ to 3 inches in diameter or length. Individual brioches are usually baked in the round fluted molds (B and D), although these molds can serve for tartlets and entrée pastries too. Baby savarins are formed and baked in the ring mold, F, while cornets and rouleaux are formed around the metal cream horns (H and K) and tubes (G and L).

CUTTERS—DÉCOUPOIRS; EMPORTE-PIÈCES

If you are going into serious pastry work, sets of round and oval cutters neatly packed in tin boxes make storage and retrieval no problem at all. Oval cutters come plain (unis), I, or fluted (cannelés), D–H, with the smallest in the set being 1⅝ inches long and the largest 4¾ inches. Sets of plain (J) and fluted round cutters (K–O) go from ⅝ inch to 4 inches in diameter. The tiny cutters in the foreground, découpoirs à truffes (P–X), make designs in truffle slices, egg whites, and other small decorative elements for aspics and pastries. Something like the ravioli wheel (B), the large Italian wheel (A), or the pastry wheel (C) is always useful for pie doughs, puff pastries, and general dough cutting.

When you must prick the sheet of dough for Napoleons, all over at ¼-inch intervals, a fork takes quite a number of minutes while the roller pricker (Y), which doubles as a meat-tenderizer, covers the area in a few passes; its cast-aluminum head is 2 inches in diameter and its sturdy wooden handle is 4 inches long.

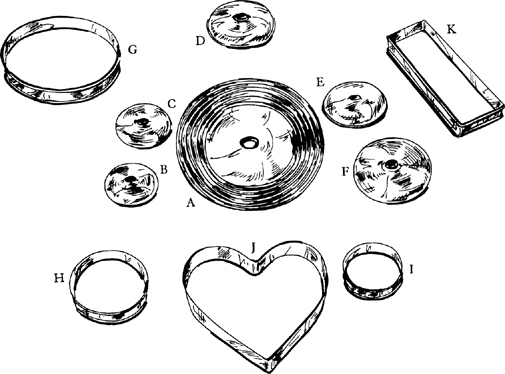

FLAN RINGS AND VOL-AU-VENT CUTTERS

Flan rings, formes sans fond (G,H,J,K, and I), come in all sizes and many shapes; they are designed especially for making the free-standing tart shells, pie shells, and quiches illustrated in Volume I, pages 143–5. A set of graduated vol-au-vent cutters (A–F) comprises 12 disks slightly raised to provide a finger hold in the center; disks range in size from 4 to 10½ inches in diameter. They are invaluable not only for cutting the vol-au-vent, but also for making circles in floured pastry sheets, like the cookie cups, or for any other circular cutting or marking operations, like the free-standing tart shells.

SOUFFLÉ DISHES AND BAKING DISHES

When you are instructed to “bake the dessert in an 8-cup cylindrical mold or dish, such as a charlotte, 4 inches deep,” A, D, and E are the dishes to use. The French charlotte molds (A and D) are the most useful baking dishes you can have in your kitchen, because you can bake in them, mold in them, caramelize them, heat them on top of the stove as well as in the oven, and you can serve from a napkin-wrapped charlotte mold. Be sure you buy the all-purpose type in tin-washed metal, tôle étamée; there are some models in flimsy aluminum that are good only for cold desserts. Useful sizes are the 6- and 8-cup models, although 3-cup, 4-cup, and very large sizes may fill some occasional needs. The American flameproof ceramic baking and soufflé dish (E) is excellent too, and a little deeper than the charlottes. French ovenproof white soufflé dishes (B and C) are attractive for baking and serving; for soufflés, tie a paper collar around them to hold the puff, as illustrated in Volume I, page 162.

Although you can make do with other methods, the traditional hinged mold for pâtés is comforting to own, decorative to look at, and will produce the beautiful finished product illustrated. These are of tôle étamée, tin-washed metal, and come in many sizes, shapes, and patterns. A 2-quart (2-liter) size is the most useful when you are buying only one. If you do not know how much a particular mold will hold, set it on a large piece of heavy foil or brown paper, fill with dried beans or rice, remove mold, and measure the beans or rice.

Eggs form themselves most happily in aspic when the mold is oval; the moules á dariole ovales, B and C, hold ½ cup and come with plain or fancy bottoms. Babas are baked in tiny charlottes, E and F, or the dariole ronde, A; these hold slightly over ⅓ cup, and are useful also for individual servings of aspic, and for small soufflés and custards. The miniature fluted mold, D, is for fancy aspics.

MOLDS FOR BAKING, FOR ASPICS, AND FOR FROZEN DESSERTS

Although the Kougloff and trois frères molds (A and D) are designed for cakes, and the ice-cream mold (E and F) for bombes glacées, all of the models pictured here are useful for aspics, and all, with the obvious exception of the fish (B), would do for frozen desserts and Bavarian creams. Use a simple pattern for frozen desserts (C and G); beware of too complicated a design or you may have terrible difficulties unmolding; the pattern in H is about as far as you can go. Although more modern materials are available, we like tôle étamée, tin-washed metal, for both baking and aspics because it seasons well—meaning it seems to present few sticking problems. Tin-lined copper for aspics is pretty to look at if you do not mind the initial expense and subsequent cleaning.

WINE GLASSES

If space is a problem, you need only one type of wine glass for Bordeaux, Burgundy, Rhine wine, Champagne, or Chianti—the tulip-shaped glass (A) that holds ¾ to 1 cup; fill it slightly less than half full to give room for swirling and sniffing. Equally serviceable is the shorter glass (B). If you are going to serve both a red and a white wine at a meal, use a larger glass (A) for the red wine in proportion to the one for the white wine (B); the white wine glass is usually placed on the outside. All of these are inexpensive and should be available in any wine shop or department store, as well as in all the restaurant and hotel supply stores. For prestigious red Bordeaux and Burgundies, the large-bowled glass (F) is amusing; a normal serving of 3 ounces looks small in it but develops its fullest bouquet. If you like to see all the champagne bubbles, hollow-stemmed crystal (E) is what to look for, although some connoisseurs sniff at wide-mouthed glasses for that noble brew. Cut-crystal sherry glasses (C) will start off any gathering in an elegant manner, and the brandy snifter (D) will release after-dinner esters.

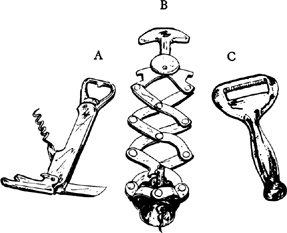

CORK SCREWS AND BOTTLE OPENERS

The reasonably priced barman’s corkscrew and bottle-cap opener (A) is designed for professionals. The flange on the left rests on the neck of the bottle to give you leverage, while the knife blade on the right, extended for display here but folded into the body of the opener when not in use, is for cutting the lead-foil cap off the wine bottle. The familiar French zig-zag (B) does a good job of leverage when corks are stubborn, and the heavy bottle-cap opener (C) is highly efficient.