The theory presented here has a variety of implications that can add significantly to our understanding of the history of modern art, and a number of these will be considered later, in chapter 4. Before proceeding to those applications, however, it is useful to examine three important questions that arise in the course of using the theory to explain artists’ careers. One of these involves the level of simplification used by the theory, and how the two categories I have described in fact stand for a continuous range of variation in practice. The second concerns whether artists can change categories during their careers. And the third considers whether some important cases that appear anomalous are in fact contradictions of the theory. Discussing these three questions can clarify the use of the theory and avoid some possible misconceptions about its predictions.

If the artist carries through his idea and makes it into

visible form, then all the steps in the process are of

importance. . . . All intervening steps—scribbles,

sketches, drawings, failed works, models, studies,

thoughts, conversations—are of interest. Those that

show the thought process of the artist are some

times more interesting than the final product.

Sol LeWitt, 19671

To this point, the distinction between conceptual and experimental approaches has been treated as binary. Yet as in virtually all scientific analysis, the true distinction between these concepts is not qualitative but quantitative. This does not mean the binary distinction is not valid or useful; as the preceding empirical measurements have illustrated, the distinction is valuable in understanding artists’ careers. The usefulness of the distinction is analogous to the value of the distinction made by economists between theorists and empiricists. Although we recognize that much, if not most, research is based on both theory and evidence, the balance between the two is normally very unequal, and it is rarely difficult to identify in which area any particular work makes its real contribution.

Economists often speak informally of highbrow and lowbrow theorists, to refer to differences in the degree of abstraction the scholar typically uses. In similar fashion, we can ask not only how to distinguish conceptual from experimental artists, but how to understand systematic differences in the practices of artists within both groups. Doing this may help us to gain a better understanding of artists’ life cycles, and it is likely to give us a deeper appreciation for the problems modern artists have confronted, and how they have solved them.

For present purposes, I propose to distinguish between two types of practitioner—extreme and moderate—within both the conceptual and experimental approaches. One dimension along which many artists can be arrayed with some confidence is the degree to which they make decisions about a work of art before as opposed to during the execution of the final work. This is the dimension I will consider here.

Taking first conceptual artists, it might seem that extreme practitioners are most readily described and identified: they are artists who make all the decisions for a work before beginning it. It is unclear, however, if this practice is literally possible. There are artists who came close to it, and perhaps achieved it, during the 1960s, by making plans for their work and having these plans executed by others. The artists often did this not simply by describing a desired image, but by specifying the process by which the work was to be made. Yet even in these cases the artists often supervised the execution, and in most cases retained the right of approval of the final work—thus continuing to make decisions, or at least retaining the option of making decisions, after the planning stage. Andy Warhol approached the extreme of complete preconception in the silk-screened paintings based on photographs that he began to do with his assistant Gerard Malanga in 1963. Warhol would begin by selecting a photograph from a magazine or newspaper. He then sent this to a silk-screen manufacturer with instructions about the size of the screens and the number of colors he wished to use. The printers would deliver the screens to Warhol’s studio, which he appropriately called the Factory.2 An assistant would then press a variety of inks through these screens to create the image on canvas. Warhol sometimes helped; Gerard Malanga explained, “When the screens were very large, we worked together; otherwise, I was pretty much left to my devices.” Warhol’s intent was apparently to accept all the paintings produced in this way. Thus Malanga recalled: “Each painting took about four minutes, and we worked as mechanically as we could, trying to get each image right, but we never got it right. By becoming machines we made the most imperfect works. Andy embraced his mistakes. We never rejected anything. Andy would say, ‘It’s part of the art.’ ”3 Malanga’s account suggests that no decisions were made by Warhol after the initial selection of the photographs and paints, though his use of the first-person plural might raise the question of whether Warhol also automatically accepted works made by Malanga working in Warhol’s absence.

Another approach to the extreme of complete preconception was described in Sol LeWitt’s rules of 1971 for the execution of his wall drawings. LeWitt stipulated that the artist planned the drawing, which was then realized, and interpreted, by a draftsman. LeWitt recognized that “the draftsman may make errors in following the plan. All wall drawings contain errors, they are part of the work.” Yet LeWitt left open the question of whether the artist was to play any role after the planning stage when he declared, “The wall drawing is the artist’s art, as long as the plan is not violated.”4 Since LeWitt did not explain who would determine whether the plan was violated, or according to what criteria, his qualification left the possibility of a role for the artist after the planning stage.

Leaving aside these relatively minor questions about the practices of Warhol and LeWitt, it is clear that they should be classified as extreme conceptual artists. Yet for most of the modern era, having a painting executed entirely by someone other than the artist was not an option. Any artist making a painting obviously makes innumerable decisions in the process, as to what materials to use, where and when to work, and so on. Yet the real issue here does not concern these routine procedural decisions, but rather the major decisions that have the greatest impact on the appearance of the finished work. In this regard it is possible to define an extreme conceptual painter as one who makes extensive preparations in order to arrive at a precisely formulated desired image before beginning the execution of the final work.

Clear examples of modern artists who created these precise preparatory images can be cited. Georges Seurat’s preparations for his early masterpiece, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte, involved making more than 50 studies, including drawings, painted wood panels, and canvases.5 The painting was considerably more complicated than his earlier major work, Une Baignade à Asnières: “The greater complexity of the subject he planned to offset by completer documentation.”6 Seurat’s preparations led to a painting approximately one-tenth the size of the final work that has been titled “Definitive Study for ‘La Grande Jatte.’ ”7 By the time he executed the final canvas, he therefore knew precisely what he wanted to do:

Standing on his ladder, he patiently covered his canvas with those tiny multi-colored strokes. . . . At his task, Seurat always concentrated on a single section of the canvas, having previously determined each stroke and color to be applied. Thus he was able to paint steadily without having to step back from the canvas in order to judge the effect obtained. . . . His extreme mental concentration also enabled him to keep on working late into the night, despite the treacherous character of artificial lighting. But the type of light in which he painted was unimportant, since his purpose was completely formulated before he took his brush and carefully ordered palette in hand.8

Henri Matisse’s preparations for Luxe, calme, et volupté, the large Divisionist painting he produced in 1905, occupied the entire preceding winter. He not only made a series of drawings and smaller oil paintings, but at the end of these studies he drew a full-scale cartoon, or charcoal drawing on paper, of the work. He then had his wife and daughter transfer this drawing to canvas using the traditional technique of pouncing.9 The use of this mechanical procedure clearly points to Matisse’s wish to begin his painting from an unaltered replica of his final preparatory drawing.

The extensive preparations for these two major paintings, involving a large number of studies made over a considerable period of time, culminated in both cases in elaborate preparatory works that appear to signal that each artist had succeeded in making all the major decisions for his painting before he began to work on the final canvas. This identifies Seurat and Matisse as extreme conceptual painters.

To identify the opposite end of the spectrum being examined here, we can consider extreme experimental artists. Their description appears equally straightforward: these should be artists who make no decisions for a painting before beginning to create what will become the final work. This extreme is of course not literally possible. The artist must obviously make some preparations for a painting, by buying materials, having a place to work, and the like. But as previously we can put aside these routine problems and consider only those decisions that significantly affect the specific appearance of the finished work.

We can readily find examples of modern artists whose goal it was to begin their works entirely without conscious preconception. A number of Surrealist painters began their paintings with what they called automatic drawing. André Masson, for example, would begin a work by allowing his brush to move freely over the canvas. “Only after the drawing was well under way did Masson permit himself to ‘step back’ to consider the results.”10 The shapes he saw on the canvas would then suggest forms to him, and he would develop these into a finished image. Under the influence of the Surrealists, a number of the Abstract Expressionists also adopted automatism as a device to begin their paintings. The most celebrated of these was Jackson Pollock. He explained in 1948 that he would tack an unstretched length of canvas on the floor, then begin to work by dripping paint on it from all four sides: “It is only after a sort of ‘get acquainted’ period that I see what I have been about.”11 Like Masson, Pollock would then examine the pattern on the canvas and work toward developing this into a coherent composition. Pollock’s avoidance of preconception was such that often it was not until he was in the final stages of working that he would decide how large the final painting would be, and how it would be oriented.12

Identifying the extremes of both approaches is thus relatively easy; the more difficult problem is to separate the moderate conceptual from the moderate experimental artists. Artists in both of these groups make some preparatory studies for their paintings, but these are not as extensive as the meticulous preparations of the extreme conceptual artists. Where do we then draw the line between conceptual and experimental?

One resolution of this problem could be to consider other dimensions of the artists’ work, including whether their goals are visual or ideational. This is obviously something we should do before making definite assignments of artists for whom there is any uncertainty regarding whether they preconceive their works. Yet it is worth working a bit more on the latter dimension before proceeding to other criteria. The test I would propose for separating moderate practitioners of the two types is whether their preliminary works suggest that they have in fact made the major decisions about the appearance of the images in their paintings before beginning to execute them.

Examples are obviously necessary to clarify this criterion. In 1860, Edouard Manet made a preparatory drawing for a painting of his parents that he squared up for transfer to the canvas. The drawing’s exact resemblance to the finished work and the squaring-up together indicate that Manet had precisely preconceived the double portrait.13 On these grounds, we might identify Manet as a conceptual painter. Yet this painting dates from a period before Manet had made a major contribution, and he did not often make similar full compositional studies in later years. During 1862–63, however, Manet made a small number of drawings of reclining nudes that several scholars believe to have been explicitly related to his celebrated Olympia of 1863. Theodore Reff discusses four such drawings and concludes that “none corresponds to the painting, whereas the final study, executed in watercolor over a swift pencil sketch, is virtually identical.”14 Reff’s judgment is consistent with the observation of Manet’s friend, the critic Théodore Duret, that “in his early years, his favorite method was to use watercolor for the preliminary studies for his pictures, in order to establish the proper color-scheme and composition.”15 The combination of a limited body of preparatory works with a single small study that closely resembles the finished painting, which itself ranks as one of his major achievements, situates Manet as a moderate conceptual innovator in this scheme.

Claude Monet serves as an example of a moderate experimental artist. In his study of Monet’s technique, John House observed that Monet did make sketches and drawings to record possible compositions for his paintings, but argued that “they were not preparatory studies for individual paintings, but rather preliminary notations of possible viewpoints, a sort of repertory of potential subjects, which Monet might use in deciding which motifs to paint and how to frame a particular scene.” The use of the sketches to identify a motif before beginning the final work means that Monet was not an extreme experimental artist: unlike Masson and Pollock, he had a clear idea from the outset of what his subject was to be. Once Monet had selected a motif, however, the drawings played no additional role in the production of the final work: “Once he fixed on the viewpoint for a painting, the drawings would have no further use.” House describes precisely why Monet’s practice identifies him as an experimental artist according to the definition used here: “His search for a promising subject completed, whether with or without the assistance of drawings, the moment of precise formulation came when Monet first confronted his bare canvas. The essential forms of a picture were generally established in the early stages of its execution, in an initial mapping out which often included elements of considerable complexity.”16 Thus the specific formulation of the images in Monet’s paintings was not determined before he began a painting, but during its execution.

Monet’s goals often required him to make significant changes in his paintings during the working stage. House observed that “the execution of the canvas was not one continuous progression from the discovery of an interesting effect to its final pictorial realization. Difficulties might arise at any stage, and the variety of things that might go wrong helps to highlight the particular points in Monet’s working process where decisions had to be taken.” Monet’s working method also evolved over time: “The frequency and extent of the pentimenti to be found in his paintings increase during the 1880s and 1890s—a further indication of the growing complexity of his methods during these years.”17

Many of the changes in Monet’s paintings were caused by his insistence on “painting directly in front of nature,” as his scenes might change more quickly than he could capture them. This was sometimes caused by human agency, as when boats were moved on the beach at Etretat in stormy weather, but it was often due to natural causes: “Water levels may be raised or lowered; the state of wind or waves may change; snow may be added or erased; the angle or quality of lighting may be transformed; and the seasons themselves may be altered.”18 Evidence of Monet’s willingness to change his paintings in the course of their execution has been provided by recent X-ray examination of some of his works. So, for example, in On the Seine at Bennecourt, executed in 1868, X-rays show that the figure of a child was painted out of an earlier version and replaced by a dog. Similarly, X-ray analysis of his Bathers at La Grenouillère (1869) revealed a number of revisions in the composition made during its execution and led a group of scholars from England’s National Gallery to describe its production as “impulsive and experimental.”19 The evidence of these changes testifies to the sincerity of Monet’s advice that “one ought . . . never be afraid . . . of doing over the work with which one is not satisfied, even if it means ruining it.”20

Much more work remains to be done, in studying the practices of many more painters, before the scheme proposed here can be considered fully developed. Yet these examples suggest that it may be useful to consider the experimental-conceptual distinction not simply as a binary categorization, but rather as a quantitative difference. In this view there is a continuum, with extreme practitioners of either type at the far ends, and moderate practitioners of the two categories arrayed along the intermediate positions of the scale. The greatest difficulties in categorizing painters will obviously arise among the moderates of both groups, who may appear to be quite similar in their practices. Yet close examination may often allow them to be separated and classed clearly as experimental or conceptual, according to whether, in Reff’s terms, any single preparatory work is “virtually identical” to the finished work, or whether, in House’s language, the “essential forms” of their pictures were established only during their execution.

The need for careful study of artists’ methods in making these distinctions is occasioned by the fact that subtle differences in practices can be associated with major differences in artistic goals. At the start of his career as a painter, Paul Gauguin studied informally with Camille Pissarro. A recent monograph argued that Gauguin’s temperament would not have attracted him to the direct approach of Monet, Renoir, or Sisley, but would have led him to prefer Pissarro’s “careful preparation of the composition of a painting.”21 Consistent with this position, a recent analysis of Pissarro’s method produced the conclusion that among the leading Impressionists, Pissarro was apparently “least comfortable with the direct rendering and informal compositions that characterized Impressionism in the early 1870s.”22 Neither Pissarro nor Gauguin can be placed at either of the extreme positions on the spectrum described here. Yet the significant question is whether both should be placed at the same intermediate position: Did they share a moderate experimental or moderate conceptual approach? In fact, the answer appears to be that they did not; a difference appears between the practices of teacher and student that places them at different positions within the middle range of the spectrum considered here, on opposite sides of the divide between experimental and conceptual. In 1886, Gauguin began to square up preparatory figure drawings for transfer to the canvas, and thereafter, during the years in which he produced his most important work, he regularly followed this process in preparing to paint the major figures in his paintings.23 In contrast, although Pissarro accumulated scores of drawings of individual figures that he could place in his paintings as he desired, he rarely if ever transferred these drawings to the canvas by a mechanical process like squaring-up. Thus the authors of a study of Pissarro’s drawings concluded that they were rarely made for any specific projected painting, and that his preparatory process was “as experimental as the manner of painting itself.”24 Gauguin’s desire to preconceive central elements in his paintings, and Pissarro’s avoidance of doing so, appear symptomatic of the substantial difference that arose in their artistic goals and caused a rift between the two friends. Thus Gauguin emerged as a leading Symbolist painter in the late 1880s, having arrived at the belief that artists should not copy nature too closely, since “art is an abstraction.”25 In contrast, Pissarro remained steadfastly committed to the visual goal of “capturing the so random and so admirable effects of nature.”26 The contrast in their goals confirms the categorization, initially based on consideration of their preparation for their paintings, of Pissarro as a moderate experimental painter, and Gauguin as a moderate conceptual one.

An interesting issue related to the placement of artists on the experimental-conceptual spectrum concerns possible differences between their desired and actual practices. A variety of constraints, including existing technology as well as artists’ abilities, may prevent artists from achieving the degree of preconception of their work that they would like. An apparent example has been revealed by recent research. Thomas Eakins was a quintessential extreme conceptual artist. He planned his paintings meticulously, regularly making preparatory drawings of individual figures, elaborate perspective studies, and eventually full compositional studies for his paintings, which he then transferred to canvas through the use of a grid. Eakins was so committed to achieving representational accuracy that when possible he would borrow from boatbuilders the plans they had used to build the boats he painted.27 A great deal of attention has recently been given to the discovery by two conservators that Eakins began a number of paintings by projecting photographic images onto his canvases, which he then traced to establish the contours for figures and objects.28 Much less attention has been devoted to another finding of the conservators, however. In examining Eakins’s paintings, they found an element for which his procedures contrasted sharply with the careful preconception of his compositions. Thus they observed that Eakins “often followed an indirect course of successive approximations toward a harmonious arrangement and ordering of color.” Color frustrated Eakins, for it posed complicated problems that he could not solve to his satisfaction in advance. Early in his career he complained of his inability to use color without the need to “change & bother, paint in & out.” Color presented problems that were extremely complicated: “There is the sun & gay colors & a hundred things you never see in a studio light & ever so many botherations that no one out of the trade could ever guess at.” Lacking a satisfactory way of determining color relationships before he began a painting, Eakins followed a systematic process in which he applied layers of paint, working incrementally from brighter to darker colors in the course of executing a painting. Eakins clearly considered this working by stages to be the lesser of two evils. Thus he was appalled at Delacroix’s attempts “to seek the tones throughout his painting at the same time”; he found the results “abominable” and attributed this to the fact that Delacroix worked intuitively, and thus “didn’t have any process” to find the proper color relationships.29

Eakins’s response to the problem of color is intriguing and suggestive. It demonstrates that even extreme conceptual artists may be unable to plan their works as completely as they would like. Eakins’s solution was to design a process that advanced systematically, and thus minimized the impact of any single decision that had to be made during the process of execution. This example appears to open up a wider research agenda, of examining how other conceptual artists have coped with obstacles that prevented them from preconceiving their works as thoroughly as they would have liked.

More work remains to be done before the continuum described here can be used with confidence. A key question in determining the value of this work will involve the implications of the analysis for understanding artists’ life cycles. As demonstrated earlier, there is very strong evidence that artists’ creativity over the life cycle is systematically related to their approach, when the approach is simply measured qualitatively, as conceptual or experimental. Will the finer categorization discussed in this section add even greater explanatory power to the study of life cycles? There is currently not sufficient evidence to begin to answer this question. One conjecture might be made, however. Specifically, it might be hypothesized that extreme conceptual artists will tend to achieve their major contributions earlier in their careers than any other type of innovator. The basis of this hypothesis is that in many cases these artists’ innovations may often be both the most radical and the least complex. The former effect is a product of lack of experience, and consequent freedom from restrictions on extreme departures due to fixed habits of thought, while the latter means that the innovations can often be realized with only minimal requirements for acquired skills. But until more research is done to classify many more artists with precision, this must be considered no more than an untested conjecture.

Seurat has something new to contribute. . . . I am person

ally convinced of the progressive character of his art and

certain that in time it will yield extraordinary results.

Camille Pissarro, 188630

Seurat, who did indeed have talent and instinct, . . .

destroyed his spontaneity with his cold and dull theory.

Camille Pissarro, 189531

As is the case for practitioners of other intellectual disciplines, it appears that the typical pattern is for artists to find the approach that best suits them in the course of arriving at their mature style. The approach they settle on may not be the one in which they were originally trained. Thus throughout the modern era, many artists who have studied in academies have been taught to make careful preparatory studies for their paintings, but after leaving their schools have discovered that they preferred to work without fully preconceived images. So, for example, John Rewald observed of Cézanne that “he hardly ever did preliminary sketches, since his canvases are not the product of a long, abstract reflection but the result of direct observation which did not allow such preparations.”32 This of course applies to the mature artist. Cézanne in fact made four sketches, a watercolor, and two compositional studies for The Abduction of 1867, two preparatory drawings for his Portrait of Achille Emperaire of 1870, and at least six preparatory drawings and a compositional study for The Feast of 1872.33 Yet these paintings were made before Cézanne traveled to Pontoise later in 1872, where under Pissarro’s guidance he began to paint directly from nature and ceased to make preparatory drawings for his paintings. This practice suited him, and he followed it with very few exceptions thereafter.

Some artists have also changed in the opposite direction in the course of arriving at their mature styles. So, for example, Paul Signac worked under the influence of Impressionism early in his career. It was only after he met Georges Seurat that he quickly discovered that he preferred a conceptual approach and began to plan his paintings carefully in advance, the practice he followed for the rest of his life.34

But artists’ changes in practice in the course of arriving at their mature styles, whenever that occurs, are not at issue here. The significant question about the possibility of changes in approach is whether artists can make mature, important contributions in both experimental and conceptual approaches at different stages of their careers.

This question has never been posed directly before, so no systematic research has been aimed specifically at producing evidence that bears on it. Surveying many available detailed analyses of the careers of individual artists suggests that there have been few who have consciously attempted to change their approach after arriving at a mature style. Yet some artists’ careers do show indications that they may have made a genuine change over time from one approach to the other, and in at least one well-documented case an important artist specifically tried and failed to change approaches. A few examples can be considered here.

Edouard Manet was classified in the preceding section as a moderate conceptual artist, on the basis of the preparatory studies he did for paintings of the 1860s, including his famous Olympia of 1863. This was evidently not an uncommon practice for Manet around this time.35 Yet as is well known, Manet’s art changed considerably during the 1870s; one element of this was that “from 1870 on, Manet seldom felt the need to elaborate a preliminary composition in drawing form.”36 Nonetheless, there are specific drawings from the 1870s that are “reproduced practically unchanged in design and detail, in the medium of oils.”37 Yet X-ray analysis of Manet’s last great work, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, completed in 1882, reveals that he twice shifted the position of the reflection of the barmaid who is the painting’s central subject. These changes made in the course of executing the painting appear to be a prime source of the visual contradiction between the placement of the barmaid and the mirrored reflection of her encounter with a customer that has made the painting the subject of a vast amount of scholarly inquiry and debate. Thus an oil study Manet had made in preparation for the painting, which appears to have served as his point of departure for the final version, presents much less exaggerated distortions from a realistic portrayal of the scene.38 It is possible that the important modifications Manet made in the course of working on his final masterpiece serve as evidence that during the 1870s he had in fact evolved from his early moderate conceptual approach to a moderate experimental one, as in this time his “solution to composition became increasingly bound to the act of seeing or experiencing a motif or a scene directly.”39

Together with his friends Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro was a member of the core group of Impressionists who developed new ways of portraying nature and influenced virtually every advanced artist in Paris during the 1870s. Like his friends, however, Pissarro suffered acutely from the uncertainty that is typical of experimental artists, and during the early 1880s he appears to have become increasingly dissatisfied with his art. Thus in 1883 he confessed to his son Lucien, “I am much disturbed by my unpolished and rough execution; I should like to develop a smoother technique.”40 In 1885 Pissarro, then 55 years old, met Georges Seurat, who was just 26. Pissarro was quickly converted to Seurat’s conceptual ideas and techniques, and began to use them himself. During the next few years, Pissarro’s attempts to follow Seurat apparently involved not only using smaller brushstrokes and pure contrasting colors that were intended to achieve more luminous effects, but also greater planning of his paintings. Thus a number of his landscape drawings from this period appear to have served as compositional studies for paintings.41 In a letter of 1886 to his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, Pissarro explained that the Neo-Impressionist art developed by Seurat was based on planning and preconception: “As far as execution is concerned, we regard it as of little importance: art, as we see it, does not reside in the execution: originality depends only on the character of the drawing and the vision peculiar to each artist.”42

Pissarro’s decision to join the Neo-Impressionists was a brave departure. Although his work had not yet gained great commercial success, he was an established figure in Paris’s advanced art world, and his defection from Impressionism to join the much younger Neo-Impressionists came at considerable personal costs in broken friendships with Monet and others, as well as warnings from Durand-Ruel that his abrupt change in style would slow the growth of demand for his work. That he persisted in spite of these costs attests to the sincerity of Pissarro’s rhetoric in expressing his conviction that the conceptual approach of Neo-Impressionism represented a real advance over the unsystematic, experimental approach of Impressionism. In spite of the strength of his commitment, however, Pissarro soon found the conceptual approach of Neo-Impressionism unduly confining. In 1888 he wrote to Lucien of his frustration with Seurat’s small touches of pure color: “How can one combine the purity and simplicity of the dot with the fullness, liberty, spontaneity and freshness of sensation postulated by an impressionist art?”43 Similarly, the next year he complained to the critic Felix Fénéon of his problems with a “technique which ties me down and prevents me from producing with spontaneity of sensation.”44 In 1891, when he reported to Lucien his sadness at Seurat’s premature death, Pissarro wrote, “I believe you are right, pointillism is finished.”45 Several years later, with his customary honesty Pissarro wrote to a friend and former fellow Neo-Impressionist to explain his decision to give up the method:

I believe that it is my duty to write you frankly and tell you how I now regard the attempt I made to be a systematic divisionist, following our friend Seurat. Having tried this theory for four years and having now abandoned it, not without painful and obstinate struggles to regain what I had lost and not to lose what I had learned, I can no longer consider myself one of the neo-impressionists who abandon movement and life for a diametrically opposed aesthetic which, perhaps, is the right thing for the man with the right temperament but is not right for me, anxious as I am to avoid all narrow, so called scientific theories. Having found after many attempts (I speak for myself), having found that it was impossible to be true to my sensations and consequently to render life and movement, impossible to be faithful to the so random and so admirable effects of nature, impossible to give an individual character to my drawing, I had to give up. And none too soon!46

Pissarro’s account shows a clear awareness that an artist’s ability to use a conceptual approach was not simply a matter of choice, but instead stemmed from basic traits of personality that he did not possess. Plagued as he was by self-doubt throughout his career, Pissarro must have envied the young Seurat, who dealt in “clear certainties,” who “went his own way, sure of himself, trusting in the fertility and richness of his own esthetic sense,” and who believed he could accomplish “the mission of releasing art from the tentative, the vague, the hesitant, and the imprecise.”47 In 1886, Pissarro must have hoped that he himself would acquire these attitudes if he adopted Seurat’s artistic philosophy and practices. Within just a few years, however, he discovered that his lack of self-confidence was as immutable a feature of his personality as his need for spontaneity in painting. Thus, true to his experimental nature, in 1889 he confided to Lucien that his only certainty in abandoning his attempt to follow Seurat was that he had to continue searching: “I am at this moment looking for some substitute for the dot; so far I have not found what I want, the actual execution does not seem to me to be rapid enough and does not follow sensation with enough inevitability; but it would be best not to speak of this. The fact is I would be hard put to express my meaning clearly, although I am completely aware of what I lack.”48

Pablo Picasso’s artistic output was so vast that it is dangerous to generalize about his career without extended study, but it appears likely that as he grew older he tended to make fewer preparatory drawings for individual paintings, and that he also tended more often to produce paintings without any preparatory drawings.49 It might be supposed that this implies that as he aged he evolved from a conceptual to an experimental approach. This is not necessarily the case, however, for particularly for an experienced artist, preparatory drawings may be unnecessary for preconception of a painting. A few accounts of Picasso’s practices suggest this.

Françoise Gilot recalled that when she first went to live with Picasso in 1946, when he was 65, he tried to draw her, but was not satisfied with the results. He then asked her to pose for him in the nude. When she had undressed, Picasso had her stand with her arms at her sides:

Pablo stood off, three or four yards from me, looking tense and remote. His eyes didn’t leave me for a second. He didn’t touch his drawing pad; he wasn’t even holding a pencil. It seemed a very long time.

Finally he said, “I see what I need to do. You can dress now. You won’t have to pose again.” When I went to get my clothes I saw that I had been standing there just over an hour.

The next day Picasso began, from memory, a series of works of Gilot in that pose, including a well-known portrait of her titled La Femme-Fleur.50 Another account of Picasso’s ability to preconceive a work without the use of sketches was given by his friend and dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, to the photographer Brassaï in 1962. It involved Picasso’s production of a linocut with multiple colors, in an unusual way. Instead of the normal procedure of cutting a separate linoleum plate for each color, Picasso used only one: after printing one color, he would recut the plate and print another color. Kahnweiler observed that by repeating this process Picasso produced very complex prints, with as many as a dozen colors. Whereas the traditional approach permitted adjustments during the printing process, by allowing changes to any of the plates at the time of printing to make the separate images of the individual plates fit together with each other, Picasso’s method provided no such margin for error, since the image for each color was irreversibly destroyed when the unique plate was recut to print the next color. Kahnweiler marveled at Picasso’s ability to use this uncompromising process: “He must see in advance the effect of each color, because there’s no pentimento possible! . . . [I]t’s a kind of clairvoyance. I would call it ‘pictorial premonition.’ I was at his home a few days ago and saw him working. When he attacks the lino, he makes out or sees in advance the final result.”51 Although this issue has not been systematically studied, these anecdotes about Picasso’s practice suggest that it is possible that experienced conceptual painters, like chess masters, can preconceive their works without having to fix their preparatory images on paper.

The lack of systematic study of the careers of individual painters aimed at answering the question posed in this section makes it premature to offer any general conclusions about whether painters can change from one approach to the other. Yet as in the preceding section I can offer a conjecture, to be tested in the future. This is that whereas it may be possible for conceptual artists to evolve gradually into experimental ones, it is not likely that experimental artists can change into conceptual ones. The logic of this conjecture is that accumulation of experience and knowledge over time may allow an early deductive way of thinking to develop into a more nuanced inductive one, but that it is much less likely that the uncertainty and complexity of an artist who initially follows an inductive approach can ever be changed successfully into the simplicity and certainty of the deductive thinker.

The life of an artist is rightly a unit of study in any

biographical series. But to make it the main unit of study

in the history of art is like discussing the railroads of a

country in terms of the experiences of a single traveler

on several of them. To describe railroads accurately, we

are obliged to disregard persons and states, for the

railroads themselves are the elements of continuity, and

not the travelers or the functionaries thereon.

George Kubler, 196252

Like other behavioral relationships in the social sciences, the predicted relationships between the categories of analysis used here and artists’ life cycles are not laws, but tendencies. It is particularly important to remember this when using quantitative evidence to examine artists’ careers, because of a significant departure of the analyses presented here from the normal practice of empirical economics. Economists often carry out econometric estimation of relationships involving the human life cycle, but they invariably do this with data that represent the experiences of large numbers of people. The resulting estimates summarize the average behavior of members of the relevant groups. The behavior of many of the people included in the data sets may differ sharply from that of the average, but the measurements of population averages can nonetheless remain powerful as long as these divergent cases are relatively uncommon. In the present case, however, the estimates of artists’ life cycles given above are for individual artists. The visibility of any deviation from the typical relationship is obviously enormously magnified by this microscopic procedure, and consequently the possibility of unusual or anomalous cases should be kept in mind.

Yet although anomalies exist, some cases that initially appear anomalous can in fact be understood through relatively straightforward extensions of the analysis used here. These extensions typically involve placing the case at issue within a broader context—either seeing the career of the artist in relation to those of others or situating the innovation within the specific experiences of the artist. Several examples involving important modern artists provide illustrations.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, Claude Monet was an experimental innovator. Monet believed that progress in art was possible only with total commitment to the study of nature and long hours of work. As late as 1890, at the age of 50, he wrote a friend that he was “profoundly disgusted with painting. It really is a continual torture! Don’t expect to see anything new, the little I did manage to do has been destroyed, scraped off or torn up.” Monet’s goals were famously visual: “The further I get, the more I see that a lot of work has to be done in order to render what I’m looking for: ‘instantaneity,’ the ‘envelope’ above all, the same light spread over everything, and more than ever I’m disgusted by easy things that come in one go.”53 Although Monet was a great experimental artist, his major contribution was made at a very early age. The peak of his age-price profile occurs for work he did at age 29, and the five-year period from which the largest number of his paintings are illustrated in both the American and French textbooks is 1869–73, when he was 29–33.

These dates are hardly surprising, for they precisely locate the period when Monet was making his breakthrough innovations in Impressionism, which proved to be one of the most influential artistic achievements of the nineteenth century. During the summer of 1869, when Monet was 29, he painted with Renoir at a riverside café near Paris. Kenneth Clark called that café, La Grenouillère, the birthplace of Impressionism, as the two artists’ novel treatment of the reflection of light on the waters of the Seine produced a new technique so powerful that it not only directly affected sympathetic artists like Pissarro and Sisley, but induced a wide variety of artists whose interests were less obviously related, including Manet, Cézanne, Gauguin, and van Gogh, to experiment with Impressionist methods.54 That this seminal experimental discovery was made by Monet before the age of 30 appears to be a powerful violation of the prediction that important experimental innovations require lengthy periods of development.55

The resolution of this apparent contradiction follows from the recognition that the development of innovations need not be made entirely by individual artists. Monet’s early breakthrough appears to have resulted from his ability to take advantage of a research agenda that several older artists had begun. Art historians have long repeated Monet’s account of how, early in his career, he had initially rejected the advice of the older artist Eugène Boudin to paint from nature, but how he had then learned valuable lessons from Boudin and his friend Johan Jongkind after he had understood their methods and goals. Thus in an interview in 1900, Monet recalled that “Boudin, with untiring kindness, undertook my education,” teaching him to study nature, and that Jongkind later “completed the teachings that I had already received from Boudin.” Monet never hid his debt to his informal teachers, acknowledging in the 1900 interview that after he met Jongkind in 1862, “from that time on he was my real master,” while in 1920 he wrote to a friend, “I’ve said it before and can only repeat that I owe everything to Boudin.” Monet explained that he came to be fascinated by Boudin’s studies, “the products of what I call instantaneity.”56 But after learning the results of the research of the two older landscape painters, Monet formulated goals more ambitious than theirs, and it was only after several years of further experimentation that he discovered “the principle of the subdivision of colors” that allowed him to achieve the novel “effects of light and color” that transformed Paris’s advanced art world.57

Monet’s career illustrates George Kubler’s warning that “biographies . . . are only way stations where it is easy to overlook the continuous nature of artistic traditions.”58 The innovation of Impressionism provides an example of a substantial difference between the overall duration of a research project and the work on that project by a key member. Monet’s leadership in the discoveries of Impressionism appears to have been a consequence of his ability to build on the extended studies of the older artists: his relationship with Boudin and Jongkind was equivalent to joining a research project already in progress, and allowed him to formulate the goals and develop the techniques of Impressionism much sooner, and at a much younger age, than if he had had to work without the benefit of their lessons.

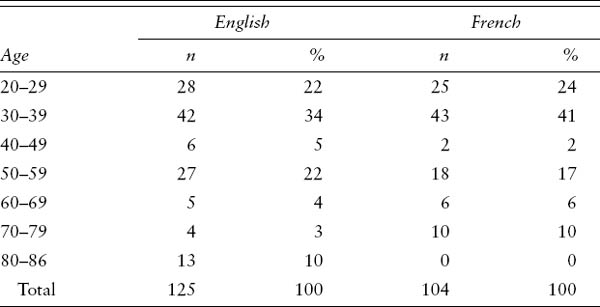

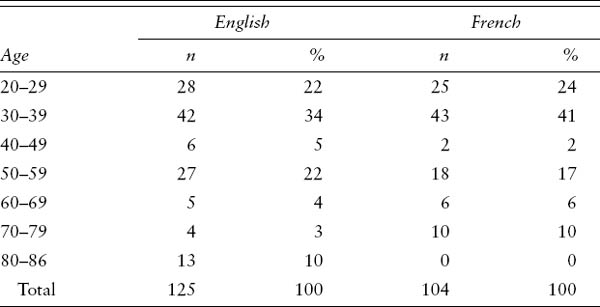

It is interesting to note that the pattern of Monet’s career reflects his experimental approach in spite of his early great achievement. Unlike many conceptual innovators who made important early discoveries and simply declined thereafter, Monet made several significant contributions later in his life. Table 3.1 presents the distributions by age of the illustrations of Monet’s paintings in the collections of textbooks in both English and French described earlier. Although both groups of scholars give clear precedence to the work of Monet’s late 20s and 30s, both distributions also include large numbers of illustrations from Monet’s 50s and for the work he did after the age of 60. The paintings presented from Monet’s 50s are from the series he executed during the 1890s, including the grain stacks, the poplars, and the views of Rouen Cathedral, while the illustrations of works he produced after age 60 give primary emphasis to the many paintings of water lilies he made at Giverny. Both of these later bodies of work made innovations that built on, and added to, the earlier discoveries in Impressionism. Thus during the twentieth century many artists would adopt the practice of painting in series. This would often stem from a belief about the value of seriality that Monet articulated in 1891, when he said of the grain stacks that the individual canvases would “only acquire their value by the comparison and succession of the entire series.”59 And during the 1950s, a number of critics and artists pointed to Monet’s late paintings of water lilies as a forerunner of Abstract Expressionism, in their size, composition, and use of color.60 Because of his experimental approach, however, Monet did not arrive at these later innovations suddenly, but, as John House observed, “this transformation . . . was the result of a protracted process of evolution.”61 Throughout his life Monet remained committed to a visual art, as just months before his death he declared that “the only merit I have is to have painted directly from nature with the aim of conveying my impressions in front of the most fugitive effects.”62

TABLE 3.1

Illustrations by Age, Monet, from Books Published in English and in French

Source: See table 2.1 and 2.2.

Vincent van Gogh’s career appears to present an anomaly of an opposite type. Van Gogh was a conceptual innovator, hailed in 1890 by the critic Albert Aurier as a great Symbolist painter who “considers this enchanting pigment only as a kind of marvelous language destined to express the Idea.”63 Yet van Gogh produced his most valuable work not in his 20s, but at the age of 36. Although van Gogh became a painter relatively late, after working as an art dealer and pastor, his greatest achievements were nonetheless made in the final few years of his life, when he had been a full-time artist for nearly a decade. Yet van Gogh’s career illustrates the necessity of a knowledge of advanced art in allowing an artist to make new contributions.

Van Gogh was largely a self-taught artist. He spent the first five years of his career as a painter in his native Holland and Belgium, where he could not see the most recent developments in modern art. Before he went to Paris, his brother Theo had told him of Impressionism, but Vincent did not know what it was. When Vincent decided to join his brother in Paris in 1886, he quickly realized that, as he wrote to a fellow artist who had remained in Antwerp, “There is but one Paris. . . . What is to be gained is progress and what the deuce that is, it is to be found here.”64 In Paris, under the guidance of Camille Pissarro, with astonishing speed van Gogh gained a knowledge of the methods and goals not only of Impressionism but also of Neo-Impressionism, and he became acquainted with Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, and a number of other young artists who were developing a new Symbolist art. Exhausted by two years of intense work in Paris, in 1888 van Gogh left for Arles, where he developed the personal form of Symbolist painting that became his distinctive contribution to modern art. Van Gogh recognized that the Impressionists would find fault with his new style, “because instead of trying to reproduce exactly what I have before my eyes, I use color more arbitrarily, in order to express myself forcibly.” His exaggerations of color and form were intended to communicate the intensity of his ideas and emotions, which he could not do within the constraints of Impressionism: “If you make the color exact or the drawing exact, it won’t give you sensations like that.”65

Clement Greenberg emphasized that “the ambitious artist . . . has to assimilate the best new art of the moment, or the moments, just before his own.”66 Vincent van Gogh did not begin to assimilate the best new art of his time until 1886, when he arrived in Paris. It was only then that he learned the techniques and motivations of the art that he would have to build on, and depart from, in order to make a significant contribution to advanced art. He did this remarkably quickly, as the landmark works of his career began to appear in 1888, just two years after he began his real education as an advanced artist, and continued from then through the remaining two years of his life. The art of these final years became a central influence on Fauvism and Expressionism. That van Gogh could make such a great contribution in such a short period is a clear consequence of his conceptual approach to art.

Roy Lichtenstein’s career provides another example of the effect of a conceptual artist’s delayed exposure to advanced art. Tables 2.5 and 2.7 show that Lichtenstein was the oldest of the leading conceptual artists of his era when he made his greatest contribution. Early in his career, Lichtenstein lived in the Midwest and upstate New York. In 1960 he took a teaching job at Rutgers University, where his colleagues included Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg, who were experimenting with Happenings and using a variety of objects as props in their performances and sculptures. Although Lichtenstein told an interviewer that at the time he had not been aware of being influenced by his colleagues, he later realized, “Of course, I was influenced by it all.”67 His art began to change almost immediately, as during 1961 he first inserted cartoon characters into his paintings, and soon thereafter he began to make entire paintings that copied comic strips. In 1963 he arrived at the technique that he would routinely use thereafter, as he began by making a small drawing that he then projected onto a larger canvas to allow him to trace the outlines for the images in his paintings.68 Lichtenstein made most of his best-known works in 1963, including Whaam!, which is the single painting by any American artist of his generation that is most often reproduced in textbooks.69 Thus although Lichtenstein did not produce his breakthrough work until he was 40 years old, he arrived at the images that embodied his major conceptual innovation within three years after his first exposure to New York’s advanced art world.

The social sciences do not produce deterministic laws from which there are no deviations, so inevitably there will be experimental artists who make major contributions early in their careers, and conceptual artists who make major contributions late in theirs. Yet what the examples considered here suggest is that we should not immediately assume that these occurrences are anomalous. Monet’s life cycle appears as an anomaly only if we consider his career in isolation. When we place it in context, it serves as a reminder that artistic innovations are not made by isolated geniuses, but are usually based on the lessons of teachers and the collaboration of colleagues. Unlike many other instances in which young artists have reacted against the art of their teachers, Monet embraced the goals and methods of Boudin and Jongkind and used their work as a point of departure for the development of even more ambitious techniques and intentions. The careers of van Gogh and Lichtenstein demonstrate that innovative artists must understand the advanced art of their time before they can make new contributions. What appears to be necessary for radical conceptual innovation is not youth, but an absence of acquired habits of thought that inhibit sudden departures from existing conventions. When van Gogh learned the methods and goals of Impressionism, he could see almost immediately that it was not an art that was suited to his temperament, but his own subsequent discoveries were then aided by his relationships with other young artists who were also reacting against Impressionism out of similar motives. Even less consciously, Lichtenstein responded just as quickly to the conceptual innovations that were changing advanced American art in the early 1960s.