Part I The Foundation—Conversational Competence

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

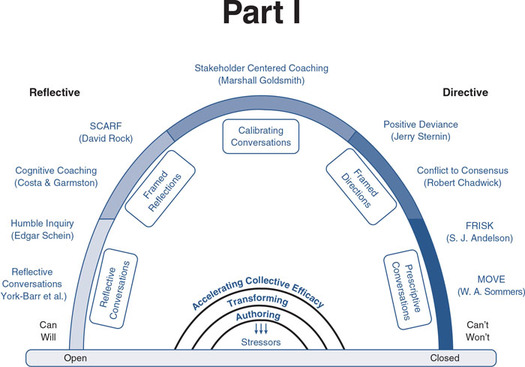

Take a few minutes and study the Professional Conversation Arc, which depicts the Nine Professional Conversations to Change Our Schools. What can you learn about this book from the diagram? Which conversations or practitioners do you already know? Which ones are new to you? For those conversations of which you are familiar, how do they relate to each other and their placement on the arc? What are you most curious to learn about?

Part I sets a context for why conversations are valuable and essential for building collective efficacy; conversations are the glue that builds cultures. While this section could be skipped in favor of going directly to the Nine Conversations, we believe it offers some important insights about why this book is so important.

Before delving more into the specifics of the graphic, we realize that we need to explain why these kinds of conversations are essential for the profession. To us, it seems obvious; to others, however, it is not so obvious. The lack of understanding about the need for professional conversations by educators, leaders, and teachers alike has been puzzling to us.

This dilemma is best told through a story. A principal new to a school offered his teachers release time to work on curricular issues. Their response was, “We do not know what we would do with the time.” He was shocked. When he was a teacher, his school had used school improvement funds to buy three days of collaboration for every grade level. That time was like gold to the teachers. The agendas were teacher directed, and some even stretched the three days into six half days. They had used it to bring their curriculum into alignment, to plan together, and to learn from each other. He knew he was a much better teacher as a result of this collaboration. This principal realized he had his work cut out for him. His teachers obviously had not done much collaborative work (indeed, the school was known for its rugged individualists).

In these next three chapters, we describe why educators everywhere would be well served to add a new knowledge domain to their practices: the skill and art of the conversation for expanding professional practices. As teachers, many intuitively understand how important language is for learning but do not actively pursue ways of improving these skills in their own professional practices. Instead, they fall back on what they know, what has served them in the past, and what is needed for the situation at hand.

In Chapter 1, we argue that conversations create bridges to understanding that open up access to knowledge coherence. By knowledge coherence, we mean that teachers seek agreement about what is essential for teaching and learning. When they don’t agree, they agree to work toward coherence and clarity about the nexus of their philosophical disagreements. Coherence does not infer agreement, but rather an understanding of the whole—the agreements, the points of divergence, and the impact of disagreements on learning.

It is only when professionals know what they stand for, can articulate how they make a difference for students, and are willing to question each other to find central truths that they can create a professional narrative of excellence.

When teachers join together and learn to articulate about shared practices, they communicate what is important to their students and to the community. They stand tall, firm in the respect given them as professionals. When this happens, they have created a knowledge legacy, which passes this professional knowledge onto newcomers.

In Chapter 2, we explore the problems created by the knowing–doing gap often reinforced by the lack of meaningful collaboration. Quite frankly, the current preservice programs are not sufficient for a 21st century profession. For this reason, schools must step in and assure that teachers become lifelong learners. The only way that this happens is through collaborative conversations.

In Chapter 3, we focus on the problems that arise in cultures that do not work well together and describe four stress reactions that block open, honest communication. We draw from adult learning theory to demonstrate how these dysfunctional communications can impede the goals of collective efficacy—the ability to author a future and to transform our thinking in the light of new data.

Together, these three chapters address this thesis: Professional conversations are essential for professional learning by describing what, why, and how these conversations fit into the context of professional learning communities. To better understand the intention of this book, take a minute before you begin Chapter 1 to review the graphic on the opposite page one more time to get a sense of the long-term outcomes of this book.