8 Stakeholder Centered Coaching—Expanding Consciousness

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

The major challenge of most executives is not understanding the practice of leadership—it is practicing their understanding of leadership.

—Marshall Goldsmith

The mismatch in perceptions between stakeholders and their appointed leaders is a common problem in schools. Leaders often do not perceive their behaviors in the same way as constituents. A leader might think he or she is a good listener, only to find out that the stakeholders do not agree. Other leaders assume no news is good news, but instead, it really means the stakeholder does not know how to give constructive feedback. There is an old adage “Don’t mistake silence for approval.” More often than not, it is because the stakeholder does not trust that the feedback would be received in a positive way. No one wants to jeopardize a relationship with a superior. And yet as leaders, to be the best that we can be, it is important to know what others’ perceptions are about how we interact.

Marshall Goldsmith (2007) has worked with businesses all over the world to build reciprocal processes to help leaders learn what their constituents think about their actions through Stakeholder Centered Coaching. Not only do leaders need honest feedback, but they need to learn how to be ready to receive this feedback as well.

The problem with feedback, as we learned through Humble Inquiry, is that it is often not received as intended. The challenge is that feedback is not always what was wanted. Even willing receivers are not always receptive to the feedback. We have all had the experience of receiving unwanted feedback. A well-meaning friend gives us feedback, and our internal voice responds, “Well, that is not want I wanted to know.” Yet external feedback is often necessary, as it exposes “blind spots” that need to be overcome in order to grow.

Initially, Bill used Stakeholder Centered Coaching to assist good leaders in becoming even better. Marshall Goldsmith’s book What Got You Here Won’t Get You There (2007) describes how to examine the discrepancy between how others view the leader and how the leader views him- or herself.

Goldsmith found that the best way to bring about change was through data collected from stakeholders. Professionals need to realize that they have blind spots, which can include habitual mindsets that keep them from understanding new information or perceptions. Stakeholder Centered Coaching breaks down the barriers by providing multiple viewpoints, making the data difficult to dismiss. Goldsmith advocates using a 360-degree feedback process, which solicits data from subordinates, superiors, and peers. Just one data point can easily be refuted; multiple data points that say the same thing cannot be ignored. When working with the data, Goldsmith suggests choosing one or two leadership behaviors and planning for regular updates on progress. Getting real feedback from those who report to the leader is critical in enhancing and sustaining long-term capacity, and these changes in key behaviors often lead to further refinements and accelerated performance.

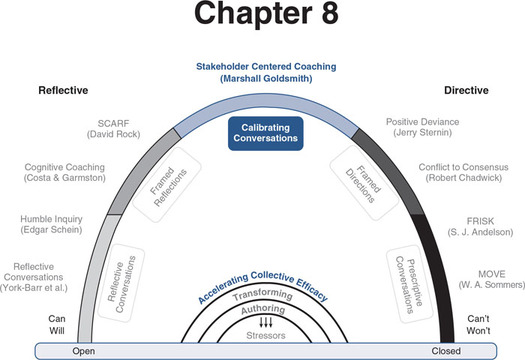

As humans, we are faced with challenges that we “do not know what we do not know.” Knowing about a problem behavior is rarely enough to change it. Doing requires, among other things, regular follow-up. Feedback to measure changes in perceptions is needed to ensure we are actually doing what we think we are doing. With an external feedback source, the coach’s job is not to give feedback, but rather to help the receiver interpret and evaluate the data to make plans for improvement and then to check in to assure follow-through. It takes the coach out of the judgment role and maintains a collaborative, problem-solving framework. We call this type a calibrating conversation because external feedback is used to determine improvements. We note here that for rest of the conversations in this book, some form of eternal evaluation or judgment will be made that determines the content.

Increasing Self-Awareness—Conversational Blind Spots

The major focus of the Stakeholder Centered Coaching process is to work with already-successful people to make improvements. The process is designed to help professionals shift thinking by receiving honest feedback and making the changes needed to improve performance. Einstein is credited with variations on this famous quote, “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” Indeed, efficacious professionals know this and seek out feedback.

The failure to model appropriate use of feedback erodes leadership capacity and trust. Leaders are vested with the job of giving feedback as part of a supervisory process. Yet when professionals allow bad habits to grow and fester and they ignore feedback, the problems expand, eroding respect. After all, supervisors often tell others to change, yet they continue ineffective behaviors and fail to model what is expected of subordinates. And sometimes, as Bill puts it, leaders need a “whack on the side of the head” to help find another way of doing business.

One goal of Stakeholder Centered Coaching is to increase self-awareness. Self-awareness is a habit of mind and must be developed and cultivated. One of the ways that Goldsmith works with leaders to help interpret the data is to uncover conversational blind spots that impede their attempts at effective communication and are judged by others in noncomplimentary terms. The list of conversational blind spots is as follows:

- ■ Inserting opinions for every situation; others see it as arrogant.

- ■ Interpreting with helpful suggestions; others see it as “butting in.”

- ■ Delegating to others; others see it as shirking responsibility.

- ■ Delegating and continuing to give directions; others see it as being overcontrolling.

- ■ Thinking they need to “hold their tongue;” others see it as being unresponsive.

- ■ Thinking that conflicts are healthy debates; others find unresolved conflicts as emotionally damaging.

- ■ Leaving the group to solve a collective problem; others see it as not caring.

Goldsmith views it a waste of valuable time and resources to coach someone who is unwilling to change and commit to improving their skills. As Marshall says, “I work with good people who want to get better.” Marshall Goldsmith is so committed to assuring change that his firm does not take payment until a final rating scale shows improvement. It should be noted that the Goldsmith’s consultant will terminate the process when the person is not responsive to the feedback or unwilling to follow through with commitments. If the leader is not going to have the discipline to follow through, there is no point investing time and energy in her or his personal and professional development. Often, this is a sign that the leader’s supervisor or board needs to consider moving this person on.

Limitations of Success

Over the years, Goldsmith was surprised to find that an additional barrier to learning was success. When successful, humans tend to bask in the good feelings of a job well done. Often, they do not reflect on their own contributions to the success, are not aware of the contributions of others, and then are surprised when the same tactics do not work in another situation. Success can shut down thinking; once an answer that works is found, many quit looking for new answers. Goldsmith writes, “The trouble with success is that it prevents us from achieving more success.” An alternative is what John Carse (1986) calls an “infinite game.” The goal of the infinite game is to keep getting better as opposed to finding one way that works and ending any further improvement (finite game). As De Witt Jones (1999) said, “Look for the second right answer.”

While coaching others, we have observed the success trap firsthand. When people are successful, they often brag about their success during the coaching. The interesting phenomenon, however, is that when queried, they are not nearly as conscious of the specific actions that directly contributed to the success. Consider this example:

Teacher: “The kids did so well today. All the kids worked well together.”

Coach: “Yes, the lesson seemed to flow, and the students were engaged. What are you learning as a teacher about how to engage these students?”

Teacher: (long pause) “I am not sure what you mean. It’s just great when the class gets into the flow.”

Coach: “And as a teacher, what do you do to make flow happen?”

Teacher: “That’s a good question. I need to think about that.”

When professionals solicit this kind of data, engage in this kind of reflection, and then change accordingly, they model open, honest appraisals of behavior. Learning from our successes is as important as learning from our failures. The goal is to be more conscious of how our behaviors—both positive and negative—impact others. By developing a culture that believes in continuous improvements, the conversations easily move toward the reflective posture.

Goldsmith has his own clearly delineated measures of successful coaching. To assure that the coaching is successful, he looks for three overt behaviors:

- ■ Courage: Learners need the courage to confront issues honestly and with humility.

- ■ Humility: Acceptance of feedback as helpful. Professionals receive feedback in the spirit in which it is given.

- ■ Discipline to follow through: There is nothing more dangerous to reputations as a failure to follow through.

Stakeholder Centered Coaching Process

Stakeholder Centered Coaching is a cyclical process not dissimilar to the reflective cycles described earlier. The difference is that the focus of the reflection is on the data obtained from stakeholders. The first step is to obtain baseline data. In Stakeholder Centered Coaching, the 360-degree feedback process is used as a way to collect this data. Usually, the person being coached is asked to give the names of five to eight stakeholders whom they perceive would provide honest data—neither best friends nor enemies. There are many online 360-degree assessments designed for businesses, which are worth the investment for high-level administrators. For Bill’s work with principals, however, he has found it more expedient and cost effective to use focused interviews of six to eight stakeholders to provide feedback to the principal, using these questions:

- ■ What are the principal’s strengths?

- ■ What are the principal’s challenges?

- ■ If the principal could change one or two things, what would they be?

- ■ Do you have any other observations or important data?

When using a more informal data collection system, as the coach, Bill gives stakeholders the following instructions:

- ■ Focus on behaviors to be improved in the future (do not dwell so much on the past).

- ■ Aim for truthfulness, not niceness, so that the feedback is helpful.

- ■ Obtain specific examples of the behavior to be changed.

- ■ Expect me to check in for additional feedback at set intervals.

When using easily identifiable stakeholders, Bill works with the principal to make sure that he or she understands the themes that emerge, that this is an improvement process, that no one is perfect, and that those offering feedback are providing positive support—even if the administrator does not see it that way. And it may seem excessive, but we also advise a strict rule: The principal may not engage in conversations about the data directly with those who volunteer to be of support. Any violation of this rule will terminate the process, and the termination will be communicated to a superior. For most, this would not be a problem, but Bill did have one principal who went right out and confronted a stakeholder because he did not like the message. It is noteworthy that this would be an example of counterproductive behavior, which would indicate that the person is not a good candidate for coaching and more than likely does not belong in the job. A conversation further down the Dashboard of Options would be in order.

Table 8.1 contains a greatly simplified Stakeholder Centered Coaching model and also modifications we have made to expand it into a principal coaching process.

Feedforward—An Open Habit of Mind

As Goldsmith (2007, p. 117) points out, “Getting feedback is the easy part. Dealing with it is hard.” Volumes have been written about feedback, yet it continues to be one of the least understood parts of the change process. Treat every piece of advice as a gift or a compliment and simply say thank you. No one expects you to act on every piece of advice; many are satisfied to know that you listened and took the information seriously. When leaders also use this feedback to shape behaviors, stakeholders notice. Ed Koch, former mayor of New York City, became famous for riding the subways of his city and asking, “How am I doing?”

Goldsmith likes to ask his clients to take a “feedforward” stance; instead of looking back, look to how this will help in the future. Feedforward helps to facilitate a positive attitude about receiving data:

- ■ Accept the data without judgment or prejudice.

- ■ Listen without interrupting or giving excuses.

- ■ Show humility and accept a possible better way.

- ■ Show courage and acknowledge what is difficult.

- ■ Show gratitude and say thank you.

- ■ Show discipline and take positive steps to change.

Feedforward focuses on what you are going to do differently. There is nothing you can do about the past; the future, however, offers an enormous opportunity to behave differently and for the better.

Make Changes Public

Another important aspect of Stakeholder Centered Coaching is to make the intended changes public. Humans get used to patterns of behavior and expect more of the same. When the pattern changes, they notice, but the disruption is not always perceived positively. Without realizing it, stakeholders can be highly critical of changes that seem out of the norm. Consider this crass statement: “Oh, boy! What workshop did he go to this week? I am not sure what he is up to, but it bugs me.” When a leader announces the intention to change and why, it lets others know that they will see new behaviors and that these behaviors are not random, but goal directed. Stakeholders are much more forgiving when they perceive that the changes are for the good of the organization. Furthermore, this public disclosure offers a chance for public reflection, which models what would be wanted from the stakeholders as well. Bill has also found that a commitment to the ongoing collection of data paired with small changes over time also communicates the serious intent of the leader.

Not all leaders are ready or open to the feedback they receive, and the conversations must necessarily become more directive. On occasion, ongoing feedback will indicate that there has been no change or, in some cases, a change for the worse. When 360-degree scores are worse, it usually means that the job is beyond his or her capacity. This means it is time to move on or change jobs. Goldsmith has found that not all are coachable, and he recommends corrective action if coaching does not work. These types of conversations are further described in Chapter 11 and Chapter 12.

Roadblocks to Learning

Some signs that people are less willing to receive and work with feedback are as follows:

- ■ A problem has been identified, but rather than trying to make the changes, they take a victim stance.

- ■ They are satisfied with their level of success and think the behaviors in question are not an issue.

- ■ They think that everyone else has the problem.

- ■ They seem to think others should tell them what to do.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

- ■ What is your relationship to feedback?

- ■ How do you receive and act on feedback?

- ■ In your life, when has feedback been ineffective?

- ■ What might you now change in your reactions to feedback?

- ■ How might you change your relationships with others based on feedback?

Goldsmith (2007) also cautions that when employees show deep blocks to learning, they may be grappling with a personal or psychological problem. This viewpoint ties directly to the stress responses described in Chapter 3. In these cases, it may be appropriate to make a referral to an employee assistance program. Now with the Internet, employers can turn to online services to get counseling for an employee. (Note: Goldsmith recommends Best Care Employee Assistance Program [www.bestcareeap.org]). Schools have not traditionally invested in these services, but we believe this is money well spent. While emotional-disturbance problems are probably not easily solved, some employees find a new lease on life by just talking through personal issues with a skilled coach.

We all face crises in our adult lives, and having support can make all the difference. As in all helping conversations, the boundary between professional coaching and psychological coaching can be blurred. We are clear: Professional coaching is not psychological coaching. When in doubt, involve a psychologist.

We conclude this chapter with the wise words of Goldsmith (2007, p. 174): “Successful people love getting ideas for the future. Successful people have a high need for self-determination and will tend to accept ideas about concerns that they ‘own’ while rejecting ideas that feel ‘forced’ upon them.” We believe Stakeholder Centered Coaching provides useful processes for dealing with complex issues of change.

Scenario 1

Diane worked as a principal for thirteen years in a university community where the parents were highly committed and supportive of the schools; they were also assertive and critical. She used to tell new teachers that every teacher at some point would get less-than-flattering feedback from a parent. She also told them that the successful teachers learned from these complaints. Diane reflects,

I didn’t realize it then, but I developed a form of Stakeholder Centered Coaching as a way of dealing with these parent complaints. I found that when teachers just brushed off these complaints, I would almost always get a similar complaint in subsequent years. I needed the teachers to learn from the feedback.

I now see working with this kind of data as a moral imperative; our job as supervisors is to help others meet the needs of all students. There is nothing like “first-person testimony” to provide notice of a problem. Parent complaints signal a failure at some level to meet a child’s needs.

Diane reports that she gained more traction and improvements through this process than all other supervision methods combined. This speaks to the power of Stakeholder Centered Coaching.

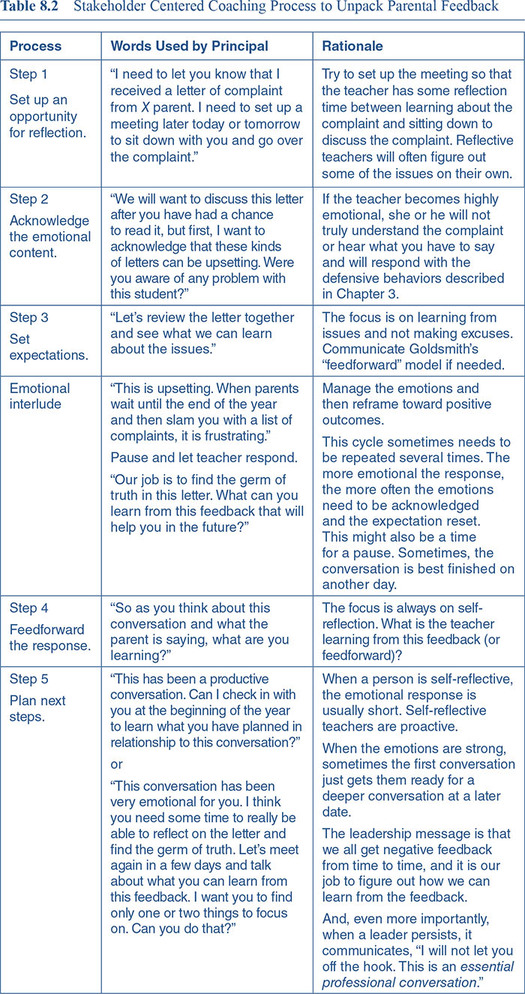

What made these parent complaints challenging was that they often came at year’s end and contained a multipage litany of everything they perceived the teacher had done wrong. Trying to find the real issue was sometimes difficult, and because the school year was over, the parent did not want to meet face to face with the teacher. Furthermore, these letters were always upsetting to the teacher, and teacher contract language limited the usefulness of anonymous feedback. Table 8.2 shows the process that Diane perfected to deal with these complaints.

Scenario 2

Bill has spent years coaching administrators both in person and over the phone. In this design, he has the principal plan for a change and also seek suggestions or feedback. He has found a few pointers for success with feedforward conversations as follows:

- He asks the administrator to pick one or two behaviors to change—ones that would be noticed by others. In other words, he wants her or him to pick changes that would make a significant, positive difference.

- Bill has the administrator describe these objectives in detail with him. Bill’s goal is to make clear the intentions to change.

- Now Bill asks the administrator to pick a colleague and describe the changes in detail to that person—then seek feedback/suggestions from the colleague regarding the changes.

- Bill instructs the administrator to accept the suggestions without judgment, denial, or debate and say thank you.

- Bill has the administrator make every attempt possible to use the suggestions while practicing the new behavior.

- If need be, Bill has the administrator seek an additional colleague to repeat Step 3.

- Bill has the administrator report on success and challenges the next time they chat.

The Final Word—Coaching Your Superintendent

Diane and colleagues used a similar process to provide feedback to a superintendent who was floundering on the job. When the school board asked for feedback, the administrators initially balked at the request. Then they realized nothing would change if they did not speak up. So a group of administrators interviewed the stakeholders and used the feedback to create a work plan based on identified leadership standards. Initially, this task was daunting—after all, the constructive feedback was going to the boss.

Diane reflects how proud she was of their work. “Not only did we provide honest, constructive feedback, but we created a document that made it clear to all what was and was not working. It reminded me that honest, constructive feedback is an ethical imperative.” She goes on, “We also had to reflect on our own leadership behaviors, as they served as a basis for our comparisons. It helped us clarify our own expectations for leadership.”

In the end, it turned out that the superintendent was not in the right position and moved on. Once again, the stakeholder process provided objective feedback; it was up to the superintendent to decide to make the changes.