[The UN is] immensely important because it represents legitimacy and international law, without which we’ll all eventually go into the ditch. It represents a place where in emergencies you can actually do something . . . that will be accepted even by people . . . who would not accept an intervention by the US or any other single country.

—Brian Urquhart, former aide and adviser to UN secretaries-general

Two documents provide the framework for the UN’s purpose, organization, and values. The first is the Charter, ratified in 1945, which functions as the Constitution does for the United States and, like the Constitution, has been amended over time to reflect changing needs. The second is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a manifesto of human dignity and value that remains as fresh and radical as it was when adopted in 1948.

The Charter was signed on June 26, 1945, by fifty nations and entered into force several months later, on October 24. The chapters and articles constitute a treaty and are legally binding on the signatories. Article 103 of the Charter stipulates that if a member state finds that its obligations under the Charter conflict with duties under “any other international agreement,” the state must place its Charter obligations first.

An Egyptian representative signs the UN Charter at the San Francisco conference, June 26, 1945. UN Photo / Yould.

Nineteen chapters lay out the major components of the organization, including its director (the secretary-general), its lines of authority, and the responsibilities and rights of its members—that is, of the governments that constitute the UN membership. Chapter I describes the purpose of the UN, emphasizing international peace and security, and Chapter II lists the qualifications for membership.

Most of the information about the elements of the new organization, including its six principal organs, appears in Chapters III through XV. Chapter IV describes the role and responsibilities of the General Assembly and its constituent member states, including the one-nation, one-vote principle and the obligation of each nation to contribute to the financial needs of the UN. According to Article 19, a member state that falls two years behind in paying its dues may lose its vote in the General Assembly, unless the failure to pay “is due to conditions beyond the control of the Member.” Chapter V deals with the Security Council, specifying its five permanent members—China, France, the Soviet Union (now Russia), the United Kingdom, and the United States—and stipulating the periodic election of ten “non-permanent” members. Article 27 of the chapter also mentions the famous “veto” that the five permanent members (P5) can deploy if they want to prevent the council from taking a specific decision, but it does so indirectly, without ever using the word “veto,” by stating that decisions of the Security Council “shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members including the concurring votes of the permanent members.”

Like the US Constitution, the Charter can be amended (Chapter XVIII), a process requiring the approval of two-thirds of the member states, including all five of the permanent members of the Security Council. And as in the United States, amendments come rarely. One change, in 1965, enlarged the Security Council from eleven to fifteen members; two other changes concerned enlarging the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

The Charter clearly envisions the members as sovereign and independent states (Chapter I, Article 2) and requires that they resolve their disputes with one another without endangering international peace and security (Article 3). Member states are also asked to avoid threatening other nations with the use of force (Article 4) and to assist the UN with any actions it may take (Article 5). The final article of Chapter I attempts to balance the internal affairs of each member state with its international actions and responsibilities. It states that the UN is not authorized to intervene in domestic affairs of a member state, but it also says that this restriction does not limit the right of the UN under Chapter VII. That chapter gives the Security Council the authority to resolve international disputes through negotiation, economic, military, and other sanctions, and even the use of force.

President Franklin Roosevelt, one of America’s most skilled political leaders, worried that the new United Nations might fail to gain approval in Congress, which is what happened to its predecessor, the League of Nations. That would have been a fatal blow to the fledgling organization. The president therefore carefully chose the US delegates to the meetings that created the UN, including important leaders in Congress and in American society. When he died in April 1945, he left behind an able team to carry out the final acts of creation and presentation to Congress.

The sole female delegate to the San Francisco conference, which met in April 1945, was Virginia Gildersleeve, an eminent educator from New York City, who was responsible for dreaming up the opening to the Charter’s preamble—“We the peoples of the United Nations”—which is based on the opening of the preamble to the US Constitution: “We the people of the United States.” She persuaded her fellow delegates that this would be a compelling way to introduce the new organization to the world, and history has borne out her insight.

After the UN was established and the United States and other nations had ratified the Charter, much work remained to be done, including addressing the question of the basic rights that humans should expect to enjoy. This time it was another Roosevelt, Franklin’s widow, Eleanor, who contributed significantly.

Eleanor Roosevelt had gained a reputation as a champion of the poor and disenfranchised. President Harry Truman now appointed her to the distinguished list of delegates to the first meeting of the General Assembly in London in 1945. There she served as the sole female member of Committee III, slated to address humanitarian, social, and cultural matters. She also became closely involved in creating the UN’s other founding document, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

After Eleanor Roosevelt’s impressive performance in London, the White House and the State Department asked her to represent the government on the nascent UN Human Rights Commission and to help draft what became the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Some experts at the time believed that the League of Nations had been fatally flawed because its charter lacked a strong statement in favor of human rights. Many supporters of the UN had originally hoped to launch the new organization with both a charter and a declaration of human rights. “I felt extremely strongly that human rights were something which simply had to be developed into an international rule,” recalls Brian Urquhart, who participated in the commission’s proceedings. “It simply wasn’t good enough to try to rely on people to behave reasonably well: they don’t. The Nazis were an extreme, but they are not unique.”

The new Human Rights Commission, with Eleanor Roosevelt as its chair, began meeting to write the declaration in April 1946. It kept meeting for the next two and a half years, in New York City and then Geneva, Switzerland, until it hammered out a consensus document. Many difficulties arose as the eighteen delegates, who represented a wide spectrum of political, social, cultural, and religious views, discussed and debated the nature of rights—indeed, the meaning of being a human being—and the proper relation between the individual and the state.

An unexpected debate arose over the use of the noun “man” to stand for “humankind” in the first article of the draft. The original text read, “All men are created equal.” An Indian woman, Hansa Mehta, complained that the word could be misunderstood to exclude women. The UN’s Commission on the Status of Women voted unanimously to ask the Commission on Human Rights to substitute “all people” for “all men.” Eleanor Roosevelt was divided on the issue because she had never felt excluded by the use of “man” in the Declaration of Independence. But she relented, and the phrase “all human beings” became the definitive term in the draft.

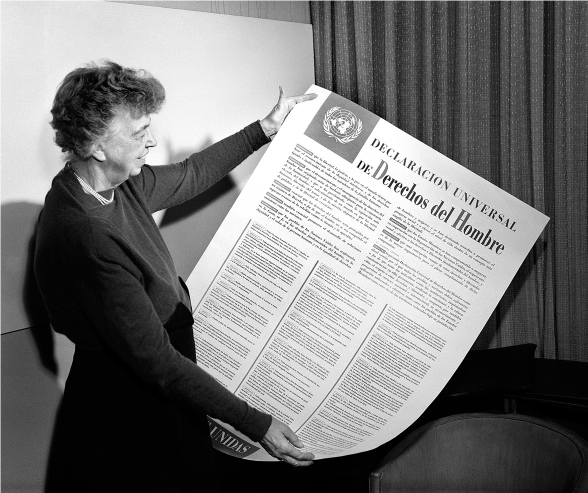

Eleanor Roosevelt with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Spanish version), November 1, 1949. UN Photo.

When the Universal Declaration was finished, it was sent to the General Assembly, which debated it anew. Finally, at 3:00 am on December 10, 1948, the General Assembly voted to adopt the draft. (The full text is printed in appendix B.)

Resting on Enlightenment ideals of human dignity, the Universal Declaration is unique both in its breadth and in its success as an international standard by which to identify the basic rights that every person should enjoy. Most human rights laws, and many national constitutions, reflect its provisions. It is an inspiration to people seeking freedom and to organizations advancing the cause of freedom and justice. Brian Urquhart praises the Universal Declaration “as one of the most important actions in the twentieth century because it changed the perception of human society from being a society where governments were dominant to a society where individual rights were the thing that everybody, including governments, had to worry about.”

Unlike the Charter, the Universal Declaration is not a treaty, and its provisions therefore are not law, but the declaration has been largely incorporated into two international treaties that came into effect in 1976 and that have been accepted by most member states: the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The UN refers to these covenants and the Universal Declaration as the International Bill of Human Rights.