This chapter includes substantial content from Nina Vredevoogd (Concur Technologies). It also includes contributions from Crysta Anderson (IBM), Michael Eggloff (IBM), and Eberhard Hechler (IBM).

Over 100 years ago, Louis Brandeis (later a justice of the United States Supreme Court) and Samuel Warren published an article called “The Right to Privacy” in the Harvard Law Review. As mentioned in chapter 2, this article defined privacy as the “right to be left alone.” Regulations and legislation around the world have since formalized and expanded this theory of privacy. According to IDC, only about 50 percent of the information in the digital universe that should be protected is actually protected.1 Although big data has many exciting applications, privacy concerns continue to pose a major challenge. Regulations and best practices are evolving very rapidly, as are consumers’ expectations about how their data is collected, kept, used, protected, and destroyed. Scarcely a day goes by without newspaper headlines reporting new and scary ways that organizations are using big data to track members of the public. This chapter includes several case studies regarding the use of big data as reported in the press.

Telephone companies can use signals from a global positioning system (GPS) to track the movement of individuals and use their calling patterns to understand their social relationships. Case Study 8.1 discusses the privacy implications of geolocation data in telecommunications.

Malte Spitz from the German Green party wanted to make a clear and convincing case for greater regulations around the privacy of big data. Mr. Spitz decided to publish the data collected from his mobile phone over a period of six months. Mr. Spitz sued the phone company and received a giant file with 35,000 data points showing his location over a period of six months. These data points represented GPS signals that were transmitted by his mobile phone even when it was not in use. Mr. Spitz then made this information publicly available. Taken individually, these data points were meaningless. However, researchers were able to construct a detailed profile of Mr. Spitz’s life by aggregating this data, integrating it with other publicly available information, and placing it on a visual map. For example, researchers combined his GPS latitude/longitude coordinates and timing data to pinpoint when he had visited political rallies, when he was on a train, which cities he visited, where he slept, where he worked, and which beer gardens he visited.

The United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) reportedly uses words on a watch list to flag blogs, Tweets, and Facebook pages for further review by investigators. Case Study 8.2 describes an unfortunate incident regarding a British couple, DHS, and Twitter.

DHS agents detained a young British couple at Los Angeles airport on suspicion of terrorist activities. A week earlier, one of them had tweeted, “Free this week, for quick gossip/prep before I go and destroy America.” The agents interrogated the pair, but did not believe the explanation that “destroy” was British lingo for partying hard. The agents also raised questions about earlier Tweets by the pair. After being held overnight, DHS agents put the couple on a flight back home and told them that the content of their Tweets had caused them to be turned away at the border.

Article 2 of the European Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) defines “personal data” as follows:

Personal data shall mean any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (“data subject”); an identifiable person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identification number or to one or more factors specific to his physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity.

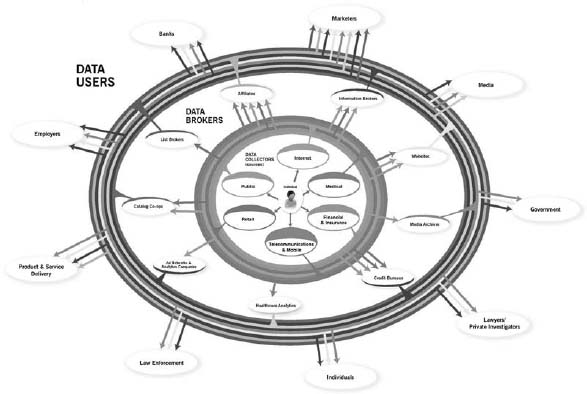

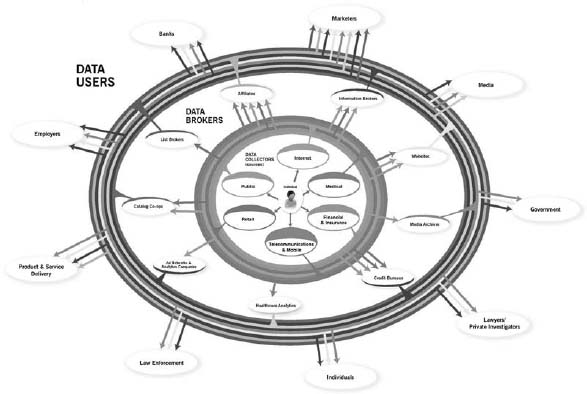

There are a number of players in the overall ecosystem for personal data, as shown in Figure 8.1:4

Figure 8.1: The personal data ecosystem.

The sheer volume, velocity, and variety of big data make it a prime target for abuse. We deal with privacy issues for web and social media in chapter 13, M2M data in chapter 14, big transaction data in chapter 15, biometrics in chapter 16, and human-generated data in chapter 17. Here, we cover generalized best practices relating to big data privacy:

8.1 Identify sensitive big data.

8.2 Flag sensitive big data within the metadata repository.

8.3 Address privacy laws and restrictions by country, state, and province.

8.4 Manage situations where personal data crosses international boundaries.

8.5 Monitor access to sensitive big data by privileged users.

Each best practice is discussed in the sections that follow.

As a first step, the big data governance program needs to identify sensitive data. In general, big data that can be linked to an individual should be treated as personally identifiable information (PII). Each jurisdiction may have its own regulations that govern the usage of this data. For example, the European Union requires a privacy impact assessment (PIA) regarding RFID data.

Big data is now blurring the lines between PII and non-PII. For example, browser fingerprinting does not rely on cookies and can uniquely identify computers and other personal devices. The term “browser fingerprint” refers to the specific combination of characteristics such as system fonts, software, and installed plug-ins that are typically made available by a consumer’s browser to any website visited.7 In another example, the country of birth, the country of residence, and account balance might not constitute PII when viewed separately. However, the combination of these three attributes might create sensitive data to uniquely identify a person born in Venezuela, living in Kazakhstan, and holding more than two million Euros in his bank account.

Given this blurring of the distinction between PII and non-PII, the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has stated that its proposed privacy framework applies to “consumer data that can be reasonably linked to a specific consumer, computer, or other device.”8 The report further states that companies must take three steps to protect this data:

Companies must take reasonable steps to de-identify the data. These steps include deletion or modification of data fields, the addition of “noise” to the data, or the use of aggregate or synthetic data.

Companies must publicly commit to maintain and use the data in a de-identified manner, and not attempt to re-identify it.

Companies should contractually prohibit service providers and third parties from attempting to re-identify the data.

Case Study 8.3 discusses the FTC investigation of Netflix, a provider of online and mail order video rentals.

Netflix is a provider of online and mail order video rentals in the United States. The FTC raised concerns about the company’s plan to publicly release purportedly anonymous consumer data to improve its movie recommendation algorithm. In response to the FTC’s privacy concerns, Netflix agreed to narrow its release of data to only certain researchers. In addition, Netflix committed to the implementation of a number of operational safeguards to prevent the data from being used to re-identify consumers. If it chose to share such data with third parties, Netflix stated that it would limit access only to researchers who had contractually agreed to specific limitations on its use.

Finally, Case Study 8.4 comes from a report in the New York Times about a retailer that used seemingly innocuous big transaction data to identify an expectant teenager before her father knew about her pregnancy.

A retailer wanted to send specially designed ads to women during their second trimester, before they were deluged with offers from other vendors. The retailer wanted to target expectant mothers during this early stage when they began buying new things like prenatal vitamins and maternity clothing. The advanced analytics team found a number of predictors that were useful to identify pregnant women. For example, pregnant women bought larger quantities of unscented lotion, special dietary supplements, scent-free soap, and large bags of cotton balls. The marketing team then used this pregnancy-prediction model to send offers to tens of thousands of female shoppers all over the United States.

About a year later, a man walked into a store and demanded to see the manager. He was clutching coupons that had been sent to his daughter, and he was angry. “My daughter got this in the mail!” he said. “She’s still in high school, and you’re sending her coupons for baby clothes and cribs? Are you trying to encourage her to get pregnant?” The manager apologized and then called a few days later to apologize again. On the phone, though, the father was somewhat abashed. “I had a talk with my daughter,” he said. “It turns out there’s been some activities in my house I haven’t been completely aware of. She’s due in August. I owe you an apology.”

Sensitive data can be stored in different parts of the organization. Big data stewards need to ensure that this data is appropriately classified in the metadata repository. Once the appropriate metadata is in place, the application can enforce the appropriate privacy policies such as, “If any application wants to access sensitive data, it needs be approved by the appropriate party.”

Certain data fields with personally identifiable information (PII) might not be subject to the required privacy safeguards. For example, a customer’s Social Security number (SSN) might reside in a field called “EMP_NUM,” and the last four digits of the SSN might be part of another field called “PIN.” As a result, just looking at the column headers is not sufficient.

Data discovery tools can discern that the EMP_NUM field in one table actually relates to the SSN in another table and to the PIN column. Data discovery tools need to look at all the actual data, and not just samples of data, as some statistical tools do.

Big data privacy presents a unique challenge because the Internet and social media are global phenomena, but laws and regulations are local. Each country, state, province, and other jurisdiction has its own laws and regulations governing privacy. Moreover, these laws and regulations are in a constant state of flux. It is not our intention to provide legal advice, but we offer examples of privacy laws and regulations in a few different jurisdictions. Each organization needs to consult with legal counsel regarding its own unique situation.

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 as a direct result of the atrocities during the Second World War. Article 12 of the declaration states the following relating to privacy:

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

The United States and Europe appear to view privacy differently, however. The United States appears to regard one’s personal information as a commodity, while the European Union (EU) regards privacy as an inalienable right. The EU’s perceptions of privacy are heavily influenced by history, such as when the Nazis used personal information collections to identify, round up, and dispose of “undesirables.”12

Historically, and particularly since World War II, Europeans have demonstrated great sensitivity to the issues of data protection, with the express purpose of preventing violations of fundamental human rights. Unlike the United States, Europe has chosen to protect an individual’s right to privacy via strict regulations and case law.

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (Council of Europe, 1950) states that “everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home, and his correspondence” subject to certain restrictions.

Article 8 of the European Union Charter of Fundamental Rights (2000/C 364/01) limits the use of personal data for secondary purposes:

…such data must be processed fairly for specified purposes and on the basis of the consent of the person concerned, or some other legitimate basis laid down by law.

The European Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) regulates the processing of personal data within the European Union. Here are some of the provisions of the directive relating to data collection practices that are common in the United States:

In January 2012, the European Commission proposed a comprehensive set of reforms to deal with new developments such as social media. The draft law is a proposal for “the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data (General Data Protection Regulation).” The new General Data Protection Regulation will repeal and replace the current European Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) and will increase the rights of individuals and the obligations of businesses. As of the publication of this book, the new regulations have not yet been adopted. We cover these regulations in some depth because we expect that other jurisdictions outside the European Union will move in the same direction.

Here are the key aspects of the proposed EU regulations:

The proposed legal framework is for a regulation, not a directive. Under EU law, a regulation automatically becomes part of the national legal system of each member state once it is passed. On the other hand, a directive prescribes only an end result that must be achieved by each member state on its own. Because 95/46/EC was a directive, it created a patchwork of national laws that made it difficult for companies to ensure compliance across the EU. Since the proposed legislation is a regulation, it is intended to create a consistent framework across the EU.

Organizations must remove personal data from their systems if an individual no longer wants his or her personal data to be processed, and there is no legitimate reason for an organization to keep it. The onus is on organizations to prove that they need to keep the data, rather than individuals to prove it shouldn’t be kept. The European Commission used the material in Case Study 8.5 to demonstrate the need for new regulations.15

Default settings should be those that provide the most privacy.

Companies must inform individuals as clearly, understandably, and transparently as possible about how their personal data will be used, so that they are in the best position to decide what data to share. Companies must also make sure that when users give their consent for companies to use their personal data, that agreement is given explicitly and with their full awareness.

Companies need to notify the supervisory authority of a personal data breach within 24 hours. Companies also need to notify data subjects (individuals) if the personal data breach is likely to adversely affect the protection of their personal data or privacy.

Organizations need to carry out an assessment of the impact of their operations on the protection of personal data when there are specific risks to the rights and freedoms of data subjects.

Enterprises need to appoint a data protection officer who reports to senior management and is responsible for compliance with the regulations.

The proposals will make it easier for individuals to access their data and give them the right to data portability, which means it will be easier to transfer personal data from one service provider to another.

The new regulations have garnered headlines because they provide for fines of up to two percent of annual worldwide turnover for international businesses.

An Austrian law student requested all the information that a social networking site kept about him on his profile. The social network sent him 1,224 pages of information. This included photos, messages, and postings on his page dating back several years, some of which he thought he had deleted. He realized that the site was collecting much more information about him than he thought, and that information he had deleted—and for which the networking site had no need—was still being stored.

Notwithstanding all of the above, data that is collected and placed on a global distributed network such as the Internet is, for all practical purposes, immortal. The regulations that prevent data collection without user consent provide the true hope for a reasonable expectation of privacy.16

Currently, no legal definition of privacy exists in the United States. As Judith DeCew notes:17

Because there is no right to privacy explicitly guaranteed in the Constitution and because the constitutional cases regarding this right are so diverse, there has been a great deal of criticism and controversy surrounding the right to privacy. It is even more difficult to describe the informational privacy protected in tort and Fourth Amendment law. The body of existing legal precedent in the United States leans toward putting the responsibility on the individual to take some explicit action to restrict the re-use of personal information once it has been voluntarily disclosed.

Unlike many countries in the rest of the world, the U.S. has no federal agency specifically focused on protecting privacy. However, Congress has passed piecemeal legislation governing privacy in certain industries:

The FTC has historically brought enforcement actions under Section 5 of the FTC Act that prohibits “unfair or deceptive acts or practices” when companies do not adhere to their published privacy policies. In addition, the FTC has gradually assumed responsibility to enforce a number of United States federal laws, including the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, and the Fair Credit Reporting Act.

The FTC is also at the forefront in terms of new regulations regarding the privacy of web and social media. In March 2012, the FTC released a report called Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: Recommendations for Businesses and Policymakers. The report does not yet carry the force of law, but it does include key recommendations to businesses and lawmakers regarding data privacy policy. Here are some of its key recommendations:

Privacy should be built in at every stage of product development and is the “default setting.” Companies should incorporate substantive privacy protections into their practices, such as data security, reasonable collection limits, sound retention and disposal practices, and data accuracy.

The report calls on companies to limit data collection to that which is consistent with the context of a particular transaction or the consumer’s relationship with the business, or as required by law. For any data collection that is inconsistent with these contexts, companies should make the appropriate disclosures at the relevant time and in a prominent manner outside of a privacy policy or other legal document.

The report highlighted the efforts of the Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC) to incorporate privacy by design. GMAC had previously collected fingerprints from individuals taking the Graduate Management Admission Test. After concerns were raised about individuals’ fingerprints being cross-referenced against criminal databases, GMAC developed a system that allowed for the collection of palm prints that could be used solely for test-taking purposes. The palm print technology is as accurate as fingerprinting, but less susceptible to “function creep” over time because a palm print is not a commonly used identifier.

The report states that companies should implement reasonable restrictions on the retention of data and should dispose of it once the data has outlived the legitimate purpose for which it was collected. Retention periods, however, can be flexible and scaled according to the type of relationship and the use of the data. For example, a mortgage company needs to maintain data for the life of the mortgage to ensure accurate payment tracking. Similarly, an auto dealer may need to retain data from its customers for years to manage service records and to inform customers of new offers.

On the other hand, location information may be used to build detailed profiles of consumer movements over time that could be used in ways not anticipated by consumers. For example, a consumer might use a mobile application to “check in” at a restaurant for the purpose of finding and connecting with friends who are nearby. That same consumer might not expect the application provider to retain a history of restaurants she or he has visited over time. If the application provider were to share that information with third parties, it could reveal a predictive pattern of the consumer’s movements, thereby exposing the consumer to a risk of harm such as stalking.

Companies should obtain affirmative express consent before using consumer data in a materially different manner than claimed when the data was collected.

The purchase of an automobile from a dealership illustrates how this standard could apply. In connection with the sale of the car, the dealership collects personal information about the consumer and his or her purchase. Three months later, the dealership uses the consumer’s address to send a coupon for a free oil change. Similarly, two years after the purchase, the dealership might send the consumer notice of an upcoming sale on the type of tires that came with the car, or information about the new models of the car. In this situation, the collection and subsequent use of data is consistent with the context of the transaction and the consumer’s relationship with the car dealership. Conversely, if the dealership sells the consumer’s personal information to a third-party data broker that appends it to other data in a consumer profile to sell to marketers, the practice would not be consistent with the car purchase transaction or the consumer’s relationship with the dealership. Companies should also obtain affirmative express consent before collecting sensitive data relating to children, finances, health, Social Security numbers, and geolocation.

The report calls on mobile phone operators to improve privacy protections, including the development of short, meaningful disclosures.

The report calls for targeted legislation to address consumers’ lack of visibility and control over the collection and use of their information by data brokers. These data brokers often buy, compile, and sell a wealth of highly personal information about consumers, but never interact directly with them. The report calls on data brokers that compile data for marketing purposes to create a centralized website where they would identify themselves to consumers, describe how they collect and use information, and detail the access rights and other choices they provide with respect to the consumer data that they maintain.

The report highlights the privacy issues that are surfaced when Internet service providers and social media platforms seek to build a comprehensive picture of consumers’ online activities.

In February 2012, the Obama administration released its “Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights” to serve as a blueprint for protecting consumer privacy.18 The proposals in the document are broadly similar to the March 2012 FTC report. In addition, The White House proposed that Congress grant the FTC the authority to enforce the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights. The White House simultaneously instructed the Commerce Department to work with the business community, privacy advocates, and other stakeholders to use the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights to establish enforceable privacy policies.

In addition to federal laws, individual states offer scattered statutes that apply only to specific sectors, such as education and child abuse records. In addition, 47 states, the District of Columbia, and several U.S. Territories have security breach notification (SBN) laws. SBN laws effectively promote privacy by requiring companies to notify consumers of unauthorized disclosures of certain kinds of personal data.19 California’s courts have adopted a particularly aggressive stance in favor of privacy, as shown in Case Study 8.6.

In February 2011, the California Supreme Court ruled against the housewares retailer Williams-Sonoma in a class action lawsuit. The court ruled that retail stores could not ask a customer to provide a postal zip code in the course of a credit card transaction. The plaintiff alleged that WilliamsSonoma used customer zip codes to obtain customer home addresses and then used the data for marketing or sold the information to other businesses. The plaintiff claimed that the practice breached her right to privacy under the California Constitution and violated the Song-Beverly Credit Card Act of 1971.

Given all of these developments, the United States appears to be gradually moving to a European approach to data privacy.

At the time of publication of this book, the Protection of Personal Information Act had not yet gone into effect in South Africa. Once this legislation does go into effect, the South African authorities will appoint a regulator to enforce compliance. South African organizations are already starting to think about how they will comply with the legislation. In general, it will require organizations to implement the following:

At the time of publication, Singapore was in the process of passing the Personal Data Protection Act, which would bring the country in line with other jurisdictions such as the EU.

The Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules were issued in 2011. These rules were issued to bring Indian privacy regulations in line with the rest of the world and to foster the continued growth of the India outsourcing industry. The privacy rules oblige organizations to notify individuals when their personal information is collected via letter, fax, or email. Press reports indicate that this meant that any personal information collected in India, or outside of India and transferred into the country, would be governed by these rules.

These rules could affect companies outsourcing their operations to India, potentially placing an unreasonable burden on outsourcers. They would need to notify individuals seeking assistance at a call center about their data handling practices and would need to obtain consent to handle personal data. However, given the importance of IT to India, press reports have indicated that these regulations would likely be relaxed.

The European Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) states that transfers of data outside the EU are permitted only if the receiving country ensures an adequate level of data privacy protection. Obviously, this would have had the effect of stifling the crossborder movement of data between the EU and the United States.

On April 19, 1999, the United States Department of Commerce issued a set of seven principles referred to as the “U.S.-EU Safe Harbor Principles.” These principles attempt to mitigate the negative commercial effects of restrictions imposed by the EU directive on data transfers to countries such as the United States that are not considered to have “adequate” privacy protection. These principles roughly correspond to the principles for data privacy protection outlined in the European Union directive:

The Safe Harbor Principles are meant to prevent U.S. companies from being sued by EU citizens or their governments for infringement of privacy, if they certify to the Department of Commerce or to a European Data Protection Authority that they will follow these principles. Certification is voluntary, but if a company were found to have violated the Safe Harbor Principles after indicating it would uphold them, it would be guilty of deceptive business practices and subject to prosecution by the FTC or other U.S. authorities. The U.S. has also concluded a similar Safe Harbor Framework with Switzerland.

The White House has claimed that 2,700 companies participate in the Safe Harbor Frameworks. By its own admission, however, the White House has stated that the Safe Harbor Frameworks do not cover sectors such as financial services, telecommunications, and insurance, which are outside the jurisdiction of the FTC.23 In addition, The Safe Harbor Frameworks have been the subject of severe criticism from a compliance and enforcement perspective. In a report called The US Safe Harbor—Fact or Fiction? (Galexia, 2008), Chris Connolly raises a number of issues, including the following:

The EU has also issued “model clauses” that need to be included by organizations when dealing with companies outside the European Economic Area (EEA) that will process personal data on their behalf. These clauses introduce a contractual obligation to secure personal information on the processor outside the EEA. As a result, U.S. companies doing business in the EU need to take precautionary measures and structure their business practices and policies to accommodate European requirements. For example, certain companies have set up websites in EU countries that are kept separate from their American businesses, so that data cannot be intermingled.

In addition, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) is working on a voluntary system of Cross Border Privacy Rules to streamline the data privacy policies and practices of companies operating within the region. APEC includes 21 members: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Chinese Taipei, Thailand, the United States, and Vietnam.

Most organizations have policies regarding access to sensitive data by privileged users such as database administrators, call center agents, and help desk personnel. However, many organizations do not have effective mechanisms to enforce these policies. To make matters worse, some of these privileged users might reside outside the country, in the case of applications that are outsourced. Here are some examples of how privileged users can potentially abuse sensitive big data:

Given all of this, the big data governance program needs to define sensitive data and establish policies to monitor access to this data by privileged users. Several database monitoring tools allow organizations to monitor when anyone issues a select statement against sensitive data. These tools are discussed in chapter 21, on big data reference architecture.

The laws and regulations regarding big data privacy continue to evolve by country, state, and province. Organizations need to work with legal counsel regarding the acceptable use of this information for customers and employees. Organizations also need to identify sensitive big data and flag it within their metadata repositories.

1. The 2011 Digital Universe Study: Extracting Value from Chaos. IDC, 2011.

2. Biermann, Kai. “Betrayed by our own data.” Zeit Online, March 26, 2011. http://www.zeit.de/digital/datenschutz/2011-03/data-protection-malte-spitz.

3. “Two U.K. citizens detained by DHS over Twitter jokes.” Homeland Security Newswire, February 2, 2012. http://www.homelandsecuritynewswire.com/dr20120202-two-u-k-citizens-detained-by-dhs-over-twitter-jokes.

4. Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: Recommendations for Businesses and Policymakers. Federal Trade Commission Report, March 2012. Page B-2.

5. Couts, Andrew. “Meet the online snoops selling your dirty laundry and how you can stop them.” Digital Trends, March 27, 2012. http://www.digitaltrends.com/socialmedia/unmasking-the-data-brokers-who-they-are-and-what-they-know-about-you/.

6. Ibid.

7. Larkin, Erik. “Browser Fingerprinting Can ID You Without Cookies.” PCWorld, Jan. 29, 2010. http://www.pcworld.com/article/188161/browser_fingerprinting_can_id_you_without_cookies.html.

8. Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: Recommendations for Businesses and Policymakers. Federal Trade Commission Report, March 2012. Page 18.

9. Ibid, page 21.

10. Duhigg, Charles. “How Companies Learn Your Secrets.” The New York Times, February 16, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/19/magazine/shopping-habits.html?pagewanted=1&_r=2&hp.

11. Section includes content from Vredevoogd, Nina. “Data Privacy Protection Law.” IMT551, 2004.

12. Craig, Terence and Ludloff, Mary E. Privacy and Big Data. O’Reilly, 2011. Page 30.

13. Cronin, Mary J. Privacy and Electronic Commerce. Hoover Press, Boston, MA, 2000.

14. “Proposed EU Data Protection Regulation—January 25, 2012 Draft: What US Companies Need to Know.” It Law Group, January 27, 2012. http://www.itlawgroup.com/resources/articles/230-proposed-eu-data-protection-regulation-january-25-2012-draft-what-us-companies-should-know-.html.

15. “How will the data protection reform affect social networks?” European Commission, January 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/justice/data-protection/document/review2012/factsheets/3_en.pdf.

16. Craig, Terence and Ludloff, Mary E. Privacy and Big Data. O’Reilly, 2011. Page 42.

17. DeCew, Judith W. In Pursuit of Privacy: Law Ethics, and the Rise of Technology. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1999. Page 21.

18. “Consumer Data Privacy in a Networked World: A Framework for Protecting Privacy and Promoting Innovation in the Global Digital Economy.” White House, February 2012.

20. “California court rules against Williams-Sonoma.” Reuters, February 10, 2011. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/02/11/us-williamssonoma-idUSTRE71A0BW20110211.

21. Claburn, Thomas. “India Adopts New Privacy Rules.” Information Week, May 5, 2011. http://www.informationweek.com/news/government/policy/229402835.

22. Vredevoogd, Nina. “Data Privacy Protection Law.” IMT551, 2004.

23. “Consumer Data Privacy in a Networked World: A Framework for Protecting Privacy and Promoting Innovation in the Global Digital Economy.” White House, February 2012. Page 33.