EIGHT

The Effects of Neighborhoods on Individual Socioeconomic Outcomes

In chapter 5, I explained one major way that neighborhood affects us: shaping our perceptions and expectations that ultimately shape our residential mobility and housing reinvestment behaviors. Here I turn to an even more significant way in which neighborhoods make us: how neighborhoods directly and indirectly shape adults and children in ways that affect their socioeconomic prospects. I first present a conceptual model showing the relationship between neighborhood context; individual residents’ attitudes, behaviors, and attributes; and opportunities for social advancement. I next provide a detailed analysis of the theory and evidence related to the issue of the mechanisms through which neighborhood context exerts its impact on us. Finally, I briefly review the evidence arising from the latest sophisticated statistical evidence that plausibly measures the causal magnitudes of neighborhood effects on a wide variety of individual outcomes contributing to socioeconomic prospects.

A Conceptual Model of How Variations in Spatial Context Generate Inequalities in Socioeconomic Outcomes

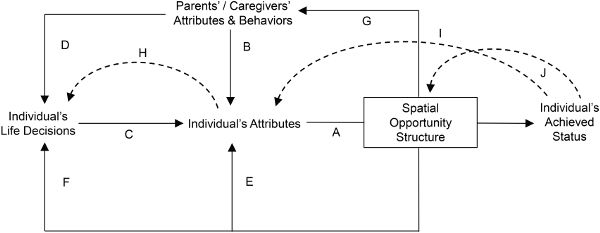

In overview, my conceptual model contends that variations in geographic context across multiple scales (neighborhood, jurisdiction, metropolitan region)—what I call “spatial opportunity structure”—affect the socioeconomic outcomes that individuals can achieve in two ways by altering

- 1. the payoffs that will be gained from the attributes that individuals possess during the period under study, and

- 2. the bundle of attributes that individuals will acquire, both passively and actively, during their lifetimes.

In the case of the first mechanism, the spatial opportunity structure serves as a mediating factor, translating a person’s bundle of individual attributes into achieved status depending on the geography of the individual’s residence, work, and routine activity spaces. In the case of the second mechanism, the spatial opportunity structure serves as a modifying factor affecting the bundle of attributes that individuals develop over time in three ways. First, it directly influences the attributes of individuals over which they may exercise little or no volition, such as exposure to environmental pollutants or violence. Second, it directly influences the attributes of individuals over which they exercise considerable volition by shaping what they perceive is the most desirable, feasible option. It does so by influencing (1) what information about the individual’s options is provided, (2) what the information objectively indicates about payoffs from these options, and (3) how the information is subjectively evaluated by the individual. These decisions early in life lead people into various path-dependent trajectories of achieved socioeconomic status and subsequent life decisions, in cumulatively reinforcing processes that can stretch across lifetimes and generations. Third, in the case of children and youth, the spatial opportunity structure indirectly influences their attributes through induced changes in the resources, behaviors and attitudes of their caregivers.

Overview and Definitions

Here I focus on understanding how the spaces in which individuals are embedded influence their socioeconomic outcomes. I conceptualize this aspect of space as spatial opportunity structure, the panoply of markets, institutions, services, and other natural and human-made systems that have a geographic connection and play important roles in peoples’ socioeconomic status achievements.1 The spatial opportunity structure includes labor, housing, and financial markets; criminal justice, education, health, transportation, and social service systems; the natural and built environment; public and private institutional resources and services; social networks; forces of socialization and social control (collective norms, role models, peers); and local political systems. By achieved socioeconomic status I mean earnings, wealth, and occupational attainment.

Various elements of the spatial opportunity structure operate at and vary across different spatial scales, as I introduced in chapter 1. This variation occurs over at least three distinct spatial scales. Across neighborhoods, variations in safety, natural environment, peer groups, social control, institutions, social networks, and job accessibility occur. Across local political jurisdictions, health, education, recreation, and safety programs vary. Across metropolitan areas, the locations of employment of various types and the associated wages, working conditions, and skill requirements vary, and there are differences in housing and other market conditions that affect individuals’ opportunities for advancement.2 Of course, since the smallest neighborhood scale is nested in all the larger ones, the attributes of all of these spaces become attached to each particular residential location, as I explicated in chapter 2. Thus, we can consider all of them neighborhood effects. It is in that sense that I employ this term here.

I view the spatial opportunity structure as affecting socioeconomic outcomes via “structuring opportunity” both directly and indirectly. It directly affects how, during a particular span of time, a set of personal attributes will pay off in terms of socioeconomic status achievements. Over a longer span of time, the spatial opportunity structure indirectly affects the set of attributes that individuals bring to the opportunity structure. Some of these indirect effects require little or no individual volition to acquire. This would include aspects of mental and physical health that may be passively acquired by living in the natural, built, and social environment, and the collective norms and local networks that influence what information people receive and how they evaluate it. In the case of children and youth, other indirect effects transpire through influences on the caregivers that affect the resources and parenting behaviors brought to bear in the household. A final indirect effect occurs by molding individual volition involved in decisions related to cognitive skill development and educational achievement, risky behaviors, marriage, fertility, labor force participation, and illegal activities. Decisions regarding these domains are so crucial in determining socioeconomic outcomes in our society that I label them life decisions. Below I amplify and illustrate these concepts and relationships with the aid of a heuristic model.

A Heuristic Model of Achieved Socioeconomic Status

In figure 8.1 I present a visual portrayal of my conceptual framework for understanding how neighborhood effects provide a foundation for inequalities in achieved status. Starting with the most basic and obvious relationship, an individual’s attributes will play a fundamental role in producing markers of achieved socioeconomic status; this is represented by path A in figure 8.1. If the individuals in question are adults, one would expect that interpersonal variations in their current bundles of achievement-influencing attributes would explain substantial variation in their contemporaneously measured achieved socioeconomic status; in the case of children, current attributes would be predictive (though with less precision) of future achieved socioeconomic status at some point when they became adults. Some personal characteristics are essentially fixed over the lifetime of the individual, inasmuch as they are associated with the vagaries of conception and birth. Such fixed attributes would include, for example, genetic signature, place and year of birth, and many (though not all) characteristics of the individual’s parents and ancestors. Other personal characteristics are potentially more malleable over a lifetime. Some may be acquired passively, such as through childrearing activities of one’s parents, as is portrayed in path B in figure 8.1. Other malleable attributes will be the product of previous decisions and actions by the individual even though, once acquired, these attributes may no longer be malleable (e.g., a physical disability or criminal record); this is portrayed as path C in figure 8.1. Some decisions are especially important in establishing a trajectory for achieved status outcomes, what I have previously called life decisions.3 These would include actions related to employment, crime, childrearing, cognitive and vocational skills, educational credentials, smoking, drinking, substance abuse and other aspects of health, and social networks. Of course, the norms, aspirations, information, and resources that individuals bring to bear in a particular life decision–making situation are substantially influenced by multiple inputs supplied by their parents or caregivers, both currently and perhaps earlier in their lives, as represented by path D in figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1. Heuristic model of the foundational role of the spatial opportunity structure in achieved socioeconomic status of individuals

Spatial opportunity structure as mediator between personal attributes and achieved status. At this point in my exposition, I take all these fixed and malleable attributes as predetermined so I can isolate one crucial role played by the neighborhood space in which the individual is currently embedded. I posit that the spatial opportunity structure serves as a mediator between individuals’ current characteristics and their socioeconomic status outcomes; see path A in figure 8.1. The spatial opportunity structure varies dramatically within metropolitan areas in the ways that it evaluates personal attributes in the process of translating them into achieved status. This means that one’s chances for such achievements will be enhanced or eroded depending on one’s place of residence, work, and routine activity space. Several illustrations serve to make my point. Even the most attractive attributes from an employer’s perspective may not yield a high income if the potential employee in question resides far from potential workplaces and cannot find a suitably fast and reliable form of commuter transportation. Underresourced, poorly administered schools with weak teachers and a cadre of disruptive, violent peers will be less likely to leverage students’ curiosity and native intelligence into literary and numerical competence and, ultimately, marketable educational credentials for those who have decided to get a diploma. Those who have accumulated little to no labor force experience may find that neighborhoods dominated by illegal or underground markets will favorably evaluate some of their attributes (e.g., present orientation, predilection for violence) that were discounted in mainstream labor markets. Women embedded in neighborhoods dominated by patriarchal norms and collective socialization into rigid gender roles will be less able to convert even the most productive personality attributes and educational credentials into socioeconomic achievements in the larger society.

Spatial opportunity structure as a modifier of personal attributes. As potent as the aforementioned effects of the spatial opportunity structure as mediator may be, it also exerts a powerful influence in three distinct ways through the passive and active acquisition and/or modification of personal attributes over time. First, through environmental exposure it directly influences some attributes of individuals over which they may exercise little or no volition. Second, it directly influences the attributes of individuals over which they exercise considerable volition by shaping what they perceive is the most desirable, feasible option in the process of making life decisions. Third, in the case of children and youth, the spatial opportunity structure indirectly influences their attributes through induced changes in the resources, behaviors, and attitudes of their caregivers. Diagrammatically, I am now turning our attention to explicating paths E, F, and G portrayed in figure 8.1.

The neighborhood’s physical and social environment constantly molds an individual’s personal attributes, even if such molding has not been consciously chosen and may be unobserved by the individual; this is represented by path E in figure 8.1. Several examples from the physical and social scientific literature illustrate my point. We know, for example, that variations in air pollution are associated with a range of health outcomes.4 Lead associated with neighborhoods with older housing stock causes permanent damage to children’s cognitive functions and attention spans.5 Exposure to violence (either as a victim or as a witness) creates physical, mental, and emotional responses that, among other things, have been shown to interfere with academic performance.6

As noted above, individuals can modify their attributes through their own life decisions. The spatial opportunity structure affects such decisions by shaping an individual’s perceptions of what is the most desirable, feasible course of action; I portray this relationship in path F in figure 8.1. The spatial opportunity structure shapes these decisions by influencing (1) what information about the individual’s options is provided, (2) what the information objectively indicates about payoffs from these options, and (3) how the information is subjectively evaluated by the individual. I explained these processes in detail in chapter 5 in the context of information used by households and property owners to form attitudes and expectations driving residential mobility and investment behaviors. Analogous processes also work when it comes to information related to the spatial opportunity structure. Therefore, for example, local networks can affect the quantity and quality of information that an individual can access regarding the opportunity set.7 William Julius Wilson’s notion of “social isolation” associated with minority neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage is illustrative of local networks bereft of information about employment opportunities.8 The collective norms operating within these networks can also shape which media of information transmission are considered more reliable sources of data about the opportunity structure. Neighborhood or school-based peers, role models, and other collective socialization forces can shape one’s norms and preferences, thereby altering the perceived prospective payoffs associated with various life decisions.

Finally, the spatial opportunity structure indirectly affects the attributes that children and youth will exhibit by shaping the resources, attitudes, health, and parenting behaviors of their adult caregivers; this portrayed as path G in figure 8.1. In my discussion of paths E and F, I described the various mechanisms of how spatial context can affect a person’s attributes; my point here is simply to note that when such persons happen to be caregivers, they become the medium through which the spatial opportunity structure transmits its impacts to those under their care. As illustration, there is ample evidence that the health (mental and physical) and resources (economic and social) of parents have a profound effect on how children develop in multiple domains.9 Thus, should the spatial opportunity structure have an impact on any of these domains through any of the causal processes previously modeled, the indirect causal link to the succeeding generation will be made. A variant of this connection is that researchers have observed caregivers altering their parenting styles in response to their perceptions of the spatial context in which their children must operate.10

Feedback effects. To complete my conceptual model, I consider several feedback effects, designated with dotted lines in figure 8.1. Once an individual makes a particular life decision, the associated attribute becomes part of the individual’s “resume” (path H in figure 8.1). This change in the portfolio of attributes will affect the individual’s opportunities in the future, perhaps irreversibly, depending on the life decision in question. Certainly the acquisition of educational credentials provides a lifelong change in one’s set of feasible opportunities; so does being convicted of a felony. Less obviously, prior life decisions may reshape individuals’ aspirations, preferences, and evaluative frames. For example, the prior decision to raise children may intensify one’s aversion to risky entrepreneurial ventures or participation in illegal activities. Similarly, if prior choices to seek long-term employment have consistently been frustrated, one’s willingness to invest in human capital development for the future and respect for civil authority may wane, leading to a pessimistic reevaluation of feasible options in the opportunity set. The previous decision to participate in gang activities may expose those individuals to different attitudinal and aspirational norms that likely alter their assessments of many options in the life decision set.

What one has achieved up to a particular moment in terms of markers of socioeconomic status (income, wealth, and occupation) also generates two feedback effects. The first is that the degree of achieved status shapes the bundle of attributes the person will develop in the future by altering the degree of financial constraint on obtaining certain attributes; I represent this by path I in figure 8.1. For example, greater accumulated wealth by a certain time in life permits people to buy superior training and credentials, maintain better health, and free themselves from constraints on employment by offloading some child-care responsibilities on to hired caretakers. One will be exposed to different sources of information, collective norms, peer effects, and role models in the workplace, depending upon occupation.

Finally, and perhaps most fundamentally, achieved status affects what spatial opportunity structure one confronts, as portrayed by path J in figure 8.1. Clearly, for most households in the United States that do not receive subsidies for housing, the neighborhood and associated characteristics of the spatial opportunity structure they will experience will depend on their ability to pay for housing. Residential sorting on the bases of income and wealth is to be expected in an economy where the market performs the main resource allocation functions, as modeled in chapter 3. Ability to pay for products and services will determine degree of exposure to other aspects of the spatial opportunity structure via interfaces with schools, transportation systems, retail shopping, and workplaces. Households with the greatest financial means select what they perceive as the most desirable niches within the spatial opportunity structure in which to live and undertake their routine activities, which are ceteris paribus the most highly priced, of course. The financial exclusivity of these spaces can be abetted by a variety of zoning codes and other development restrictions, if the well-heeled can politically dominate a local jurisdiction to serve their interests, as I explained in chapter 7. At the other extreme of achieved status, households with little to no market power are relegated by default to the least expensive residual pockets of the spatial opportunity structure: slums, ghettos, and the streets.

Cumulative causation and path dependencies. The foregoing model should make it obvious that I view the processes involved in achieving socioeconomic status as cumulative, path-dependent, and typically mutually reinforcing over time. One’s stock of attributes measured at any time will be shaped by the neighborhoods one has experienced in the past, both directly and indirectly through their influence on previous life decisions and actions by caregivers. Going forward, this current set of attributes will constrain (to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the attribute bundle and past socioeconomic achievements) the perceived life-decision options and associated expected payoffs. As illustration, a person who has dropped out of high school and served jail time for committing a felony will have far fewer options in the future for attaining higher socioeconomic status than a person who has a graduate degree and no brushes with the law. In addition, the expected financial payoffs associated with any similar life decision options they share (like working full-time) will differ significantly. In turn, these current interpersonal differences in opportunities will lead both people down different paths of life decisions in the future. Abetting this mutually reinforcing sequence of decisions over the life course is the aforementioned financial effect on which neighborhoods one can afford to access. Those whose paths have resulted in substantial achievements in status early in life can afford to occupy more privileged niches in the spatial opportunity structure, thereby providing themselves and their offspring with even better attributes and opportunities, which in turn will spawn even more productive life decisions.

The evolution of the spatial opportunity structure. The foregoing description has taken the housing market, a prime driver of the spatial opportunity structure, as predetermined. From the perspective of an individual decision maker, this is reasonable. From a longer-term general equilibrium perspective, of course, the housing market in particular and the spatial opportunity structure in general is constantly evolving, partly in response to how the population has been sorting themselves as housing demanders across the metropolitan area. As I have documented and analyzed in chapter 7, this sorting process has produced a great deal of racial and class segregation. In the next chapter I will document wide interneighborhood variations in many other contextual indicators. It is beyond the scope of this model to consider all these forces shaping the spatial opportunity structure; nevertheless, a few illustrative comments are in order.

Some of the alterations in the spatial opportunity structure may be exogenous to the actions of households, such as industrial restructuring produced by new technologies or international trade. However, the aggregate behaviors of households within a metropolitan area produced by a previous period’s opportunity structure may endogenously influence other alterations. For example, the poor quality of a neighborhood’s public school may constrain children’s ability to gain good skills and credentials. Yet, if many parents decide to participate in a political process, the result may be a reallocation of fiscal resources to improve the local school. The educational background of the parents of students living in the district also comprises an important element of constraint on school outcomes. Inasmuch as better-educated parents create more intellectually stimulating home environments, better monitor the completion of homework, and demonstrate more interest in what goes on in school, the quality of the classroom environment will improve for all students. So if, in response to inferior public education, better-educated parents move out of the district or enroll their children in private schools, the constraints on all parents who remain in the public school system become tighter. As another example, housing developers may cater to parents who have substantial status achievements by building new, high-quality subdivisions that create exclusive niches in the spatial opportunity structure. After incorporation, these niches may provide a wide range of attractive amenities and public services that encourage the success of the children living there.

Thus, those who are successful in one round of spatial status competition are in a better financial position in the next round to occupy superior neighborhoods within the evolving spatial opportunity structure, thereby improving their and their children’s odds of perpetuating this success and generating market forces that alter the structure itself over time. Conversely, those who evince few status achievements early in life are relegated to the multidimensionally inferior, least expensive neighborhoods, where they are induced by the resultant opportunity set to make life decisions that tend to perpetuate their inferior status. When some of these decisions viewed by the larger society as “social problems” become concentrated in the niches low-status people occupy, the larger opportunity structure will morph in many ways. Those with financial means move away from neighborhoods and schools of concentrated disadvantage, weakening the local retail sector and the entry-level job opportunities they provide. These same moves may strain the financial capacity of the local political jurisdiction, forcing a retrenchment in public services. In this fashion, a self-reinforcing spiral of spatial decline and individual impoverishment can be generated in certain locales, as I explained in chapters 3 and 4.

Summary of a Heuristic Model of the Spatial Opportunity Structure

Within the framework I have portrayed in figure 8.1, is it easy to comprehend how space plays a vital role not only as a foundation for current inequality, but for the perpetuation of intergenerational inequality as well. Through cumulative causation and path dependency, those with the greatest status attainments achieved early in adulthood can spatially nest in a neighborhood segment of the opportunity structure that enhances their prospects for continued success and provides their offspring with improved chances for replicating this success themselves. Over time, the spatial opportunity structure in turn evolves in ways that further benefit those with the greatest achieved status. By contrast, those who start with little typically are “stuck in place,” both geographically and socioeconomically, as powerfully documented by Patrick Sharkey.11

The Mechanisms of Neighborhood Effects

We may now probe more deeply the precise means through which the various dimensions of neighborhood context affect their residents, using the overarching model portrayed in figure 8.1. There have been many scholarly treatises about the potential causal connections between neighborhood context and individual behavioral and health outcomes.12 Though often in these works the potential mechanisms differ in labeling and categorizations, there is a broad consensus about how the underlying causal paths operate in theory. Unfortunately, there is no consensus about which mechanisms demonstrate the strongest empirical support. Perhaps this is because which mechanism dominates is contingent on the type of person and outcome being investigated. In this section, I list fifteen potential causal pathways between neighborhood context and individual behavioral and health outcomes, synthesizing both sociological and epidemiological perspectives. I provide a new conceptualization of dimensions of neighborhood effect mechanisms that uses a pharmacological “dosage-response” analogy to clarify the empirical challenges of this field of enquiry. I then review empirical studies related to neighborhood effect mechanisms and draw provisional conclusions about the dominant mechanisms operating.

How Does Neighborhood Transmit Effects to Individuals?

My synthesis of the disparate literatures in social science and epidemiology identifies fifteen distinctive types of linkages. I think it most useful to group these fifteen mechanisms of neighborhood effects under four broad rubrics: social-interactive, environmental, geographical, and institutional.13

Social-interactive mechanisms. This set of mechanisms refers to social processes endogenous to neighborhoods.

- • Social contagion: Contact with peers who are neighbors may change behaviors, aspirations, and attitudes. Under certain conditions, these changes can take on contagion dynamics that are akin to “epidemics.”

- • Collective socialization: Individuals may be encouraged to conform to local social norms conveyed by neighborhood role models and other social pressures. Achieving a minimum threshold or critical mass before a norm can produce noticeable consequences for others in the neighborhood characterizes this socialization effect.

- • Social networks: Information and resources of various kinds transmitted through neighbors may influence individuals. These networks can involve either “strong ties” or “weak ties.”

- • Social cohesion and control: The degree of neighborhood social disorder and its converse, “collective efficacy,”14 may influence a variety of behaviors and psychological reactions of residents.

- • Competition: Under the premise that certain local resources are limited and not pure public goods, this mechanism posits that groups within the neighborhood will compete for these resources among themselves. Because the outcome is a zero-sum game, residents’ access to these resources and their resulting opportunities may be influenced by the ultimate success of their group in “winning” this competition.

- • Relative deprivation: This mechanism suggests that residents who have achieved some socioeconomic success will be a source of disamenities for their less well-off neighbors. The latter may view the successful with envy or make them perceive their own relative inferiority as a source of dissatisfaction.

- • Parental mediation: The neighborhood may affect (through any of the mechanisms listed under all categories here) parents’ physical and mental health, stress, coping skills, sensed efficacy, behaviors, and material resources. All of these, in turn, may affect the home environment in which caregivers raise children.

Environmental mechanisms. Environmental mechanisms refer to natural and human-made attributes of the neighborhood that may affect directly the mental or physical health of residents without affecting their behaviors. As in the case of social-interactive mechanisms, the environmental category can also assume distinct forms:

- • Exposure to violence: If people sense that their property or person is in danger, they may suffer psychological and physical responses that can impair their functioning or sensed well-being. These consequences are likely even more pronounced if the person has been victimized.

- • Physical surroundings: Decayed physical conditions of the built environment (e.g., deteriorated structures and public infrastructure, litter, graffiti) may impart psychological effects on residents, such as a sense of powerlessness. Noise may create stress and inhibit decision-making through a process of “environmental overload.”

- • Toxic exposure: People may be exposed to unhealthy levels of air-, soil-, or water-borne pollutants because of the current and historical land uses and other ecological conditions in the neighborhood.

Geographical mechanisms. Geographic mechanisms refer to aspects of a neighborhood that may affect residents’ life courses solely due to its position in space relative to larger-scale political and economic elements, such as

- • spatial mismatch: Certain neighborhoods may have little accessibility (in either spatial proximity or as mediated by transportation networks) to job opportunities appropriate to the skills of their residents, and thereby may restrict their employment opportunities.

- • public services: Some neighborhoods may be located within local political jurisdictions that offer inferior public services and facilities because of their limited tax base resources, incompetence, corruption, or other operational challenges. These, in turn, may adversely affect the personal development and educational opportunities of residents.

Institutional mechanisms. The last category of mechanisms involves actions by those typically not residing in the neighborhood who control important institutional resources located there, or points of interface between neighborhood residents and vital markets:

- • Stigmatization: Neighborhoods may acquire stigma based on public stereotypes held by powerful institutional or private actors about its current residents. In other cases this may occur regardless of the neighborhood’s current population because of its history; its environmental or topographical disamenities; the style, scale and type of its dwellings; or the condition of its commercial districts and public spaces. Such a stigma may reduce the opportunities of its residents in various ways, such as job options and self-esteem.

- • Local institutional resources: Some neighborhoods may have access to few high-quality private, nonprofit, or charitable institutions and organizations such as benevolent associations, subsidized day care facilities, human welfare agencies, and free medical clinics. The lack of these institutions and organizations may adversely affect the personal development opportunities of residents.

- • Local market actors: There may be substantial spatial variations in the prevalence of certain private market actors that may encourage or discourage certain behaviors by neighborhood residents, such as liquor stores, fresh food markets, fast food restaurants, and illegal drug markets.

Conceptual Issues in Uncovering and Measuring Mechanisms of Neighborhood Effects

I find it revealing to employ a pharmacological metaphor of dosage-response here and frame the conceptual issues as follows: What about a particular “dose of neighborhood” might be causing the observed individual “response?” The challenges in answering this deceptively simple question are legion, and my purpose here is to present some of the major ones.15 If we are to understand deeply why aspects of the neighborhood context affect residents, we ultimately must answer seventeen questions arrayed under three overarching rubrics regarding the composition, administration, and response to the neighborhood dosage.

The composition of the neighborhood dosage. What are the “active ingredients” that constitute the dosage? What is it about this space in terms of internal social interactions, environmental conditions, geographic attributes, and reactions of external institutional drivers that is the causal agent, and how can it be measured precisely? If neighborhood is a multidimensional package of causal attributes, as is likely, we must identify and measure directly each part of the package.

The administration of the neighborhood dosage. In this realm, several questions must be addressed.

- • Frequency: How often is the dosage administered? For example, does a particular form of social interaction occur only rarely or, as in the case of air pollution, does the exposure occur during each inhalation?

- • Duration: How long does the dosage continue, once begun? Certain social interactions can vary dramatically in their length, whereas the dosage of unresponsive public services and nonexistent facilities can be omnipresent.

- • Intensity: What is the size of the dosage? How concentrated are the toxins? How weak are the local services? In the case of social interactive causes, the answers to the frequency, duration, and intensity questions will be related to the amount of time the individual spends in the neighborhood and outside the home in “routine activities.”

- • Consistency: Is the same dosage being applied each time it is administered? Do pollutants or the threat of victimization vary daily on the basis of meteorological conditions or time of day?

- • Trajectory: Is the frequency, duration, and intensity of dosage growing, declining, or staying constant over time for the resident in question? Do the individuals in a rising trajectory context evince fewer effects because they become “immune,” or evince stronger effects because their resistance is “weathered?”

- • Spatial extent: Over what scale does the dosage remain constant? How rapidly do the frequency, duration, intensity and consistency of dosage decay when the subject travels away from the residence? Do any of these gradients vary according to the direction of movement away from the residence?

- • Passivity: Does the dosage require any cognitive or physical action by residents to take effect? Do residents need to engage in any activities or behaviors, or even be cognizant of the forces operating upon them, for the effect to transpire? In the case of endogenous local social interactions, the answer is probably yes, but not in the case of the other categories of mechanisms.

- • Mediation: Does the resident in question receive the dosage directly or indirectly? For example, parents directly affected by the neighborhood may mediate neighborhood influences indirectly borne by children.

The neighborhood dosage-response relationship. Again, in this realm we must raise several issues:

- • Thresholds: Is the relationship between variation in any dimension of dosage administration and the response nonlinear? Are there critical points at which marginal changes in the dosage have nonmarginal effects?

- • Timing: Does the response to the dosage occur immediately, after a substantial lag, or only after cumulative administration? For example, you might acquire stigma as soon as you move into a certain neighborhood, but eroded health due to lack of local recreational facilities may not show up until much later.

- • Durability: Does the response to the dosage persist indefinitely? Or does it decay slowly or quickly? The developmental damage done by lead poisoning is, for illustration, indelible.

- • Generality: Are there many predictable responses to the dosage administration, or only one? Peers may influence a wide variety of adolescent behaviors, whereas certain environmental toxins may have rather narrowly defined health impacts.

- • Universality: Is the relationship between variation in any dimension of dosage administration and the particular response similar across children’s developmental stages, demographic groups, or socioeconomic groups? The same dosage of neighborhood may yield different responses, depending on the developmental or socioeconomic status of those exposed.

- • Interactions: Are dosages of other intra- or extra-neighborhood treatments also being administered that intensify the dosage’s expected response? Different dimensions of neighborhood may be not additive, but multiplicative in their consequences.

- • Antidotes: Are dosages of other intra- or extra-neighborhood treatments also being administered that counteract the dosage’s expected response? For example, efforts to improve residents’ health by building new clinics and outreach facilities in the neighborhood may appear to founder if environmental pollution in the area gets worse.

- • Buffers: Are people, their families, or their communities responding to the dosage in ways that counteract its expected response? Because residents individually and collectively potentially have agency, they may engage in compensatory behaviors that offset negative neighborhood effects, such as when parents keep their children in the home while certain violent youngsters are using the local playground.

Past Investigative Responses and Their Limitations

There are two broad sorts of approaches that social scientists have employed in an attempt to answer the above questions and uncover the dominant neighborhood effect mechanisms at work. The first consists of field-interview studies of people’s social relations and networks within neighborhoods and nonresidents’ opinions about neighborhoods, involving both quantitative and qualitative analyses of the data collected thereby. The second consists of multivariate statistical studies estimating models of how various neighborhood indicators correlate with a variety of individual outcomes for children, youths, and adults.

Field-interview studies try directly to observe potential mechanisms. In this vein, there have been numerous sociological and anthropological investigations, but they are often limited in their ability to discern the relative contributions of alternative causes because of their qualitative nature and their typical focus on only one set of mechanisms to the exclusion of others. Nevertheless, several have been revealing and remarkably consistent in their findings that allow us to rule out certain potential causes. Moreover, this style of investigation is more appropriate for probing many of the questions noted above, such as active ingredients, passivity, mediation, and buffering of dosages.

The multivariate statistical approach tries to draw inferences about neighborhood effect mechanisms from the statistical patterns observed. It has its own challenges, akin to a physician making a differential diagnosis based on a patient’s symptoms and only a partial, poorly measured medical history. One inferential notion that has been used is that if particular descriptors of a neighborhood prove more statistically and economically significant predictors of resident outcomes, they may hint at which underlying process is dominant. For example, imagine that the variable “percentage of residents in the neighborhood who are poor” did not prove statistically significant, but that the variable “percentage of residents in the neighborhood who are affluent” did prove so in a regression predicting outcomes for low-income residents. This would suggest that a positive social externality from the affluent group (such as role modeling), not a negative social externality from the poor group (such as peer effects), was present. Unfortunately, an overview of the research record typically does not produce such unambiguous results for coefficients. Moreover, most of this statistical literature is of little help to us here because it does not disaggregate findings by economic or demographic group. For example, how is one to interpret the finding from a regression model estimated over youth sampled from a variety of income groups that there is a negative correlation between the percentage of poor households in the neighborhood and an individual’s chances of dropping out of high school? One cannot make the deduction that nonpoor youth are positively influencing poor youth through role modeling. A second inferential notion often employed draws upon the assumption that different types of neighborhood social externalities yield distinctive functional forms for the relationship between the percentage of disadvantaged or advantaged residents in a neighborhood and the amount of externality generated. For example, collective social norms and social control likely come into play only after a threshold scale of the population group thought to be generating this effect has been achieved in the neighborhood, as I explained in chapter 6. We can use this logic to draw out implications for underlying mechanisms of neighborhood effects if the statistical procedures used to investigate the relationship between neighborhood indicators and individual outcome permit the estimation of nonlinear relationships. Unfortunately, as I documented in chapter 6, few extant empirical studies test for nonlinear relationships between neighborhood indicators and various individual outcomes. Moreover, even if we observe thresholds and other distinctive nonlinear relationships, it need not uniquely identify only one causal mechanism.

In what follows, I will organize the review in subsections corresponding to the foregoing mechanisms of neighborhood effects,16 bringing to bear evidence from the two approaches as relevant. Before turning to this empirical evidence, however, I note as preface that no definitive, comprehensive study of neighborhood effect mechanisms exists; none examines more than one or two of the above questions for an array of potential causal mechanisms.17 Indeed, scholars have not addressed most of the questions explicitly in the theoretical or empirical literature. Thus, one should treat my conclusions regarding neighborhood effect mechanisms as provisional.

Evidence on Social-Interactive Mechanisms of Neighborhood Effects

Social contagion and collective socialization. Numerous statistical studies have examined in detail the social relationships of youth from disadvantaged neighborhoods.18 They have identified links between deviant peer group influences and adolescents’ grade point average, mental health, antisocial behavior, school attainment, and substance abuse.19 Anne Case and Lawrence Katz’s investigation of youth in low-income Boston neighborhoods is notable because of its sophisticated efforts to avoid statistical bias.20 They find that neighborhood peer influences among low-income youth are strong predictors of a variety of negative behaviors, including crime, substance abuse, and lack of labor force participation. Stephen Billings, David Deming and Stephen Ross found with natural experimental data from North Carolina that peer effects on youth criminal behavior arise when school peers of the same race and gender reside less than one kilometer away from each other.21 This body of scholarship suggests that peer effects and role modeling among disadvantaged young neighbors often generate negative social externalities.22

However, the extent to which such negative socialization would diminish in the presence of higher-income youth is unclear. James Rosenbaum and his colleagues have provided a series of studies related to black families living in public housing in concentrated poverty neighborhoods who were assisted (with rental vouchers and counseling) in finding apartments in majority white-occupied neighborhoods of Chicago and its suburbs as part of a court-ordered remedy for the Gautreaux public housing discrimination suit.23 Though he provides one of the most optimistic portraits of the benefits that such moves can provide to black adults and their children, he does not find a great deal of social interchange or networking between these new in-movers and the original residents. Rosenbaum concludes by stressing instead the importance of role models and social norms in middle-class suburban environments for generating positive outcomes for those participating in the Gautreaux program.24 However, this optimistic conclusion has been challenged by recent qualitative case studies revealing limited role modeling between upper-income and lower-income blacks in gentrifying neighborhoods,25 and in mixed-income neighborhoods built on redeveloped public housing sites.26

The threshold notion embedded implicitly in both the social contagion and collective socialization mechanisms potentially allows them to be identified by regression-based studies that allow for nonlinear relationships between the measure of neighborhood context and the probability of the individual outcome being investigated. My review of this evidence in chapter 6 provides further support for the social contagion and collective socialization processes.

Social networks. Several qualitative studies based on field evidence investigate the social networks of blacks in US urban areas.27 They find that, controlling for personal income, those in areas of concentrated poverty typically are more isolated within their households and have fewer close external ties, especially with those who are employed or well educated. Black females’ volume, breadth, and depth of social relationships in poor neighborhoods are especially attenuated. Because job seekers in US high-poverty areas often rely upon neighbors for potential employment information, the situation appears ripe for neighborhood effects in such disadvantaged places, manifested as resource-poor social networks.

Statistical studies provide further support to the hypothesis that the social network mechanism of neighborhood effect has veracity when it comes to finding employment in the United States. Welfare participation appears to be enhanced by geographic proximity to others on welfare, especially if these proximate others speak the individual’s language.28 People who live on the same census block also tend to work on the same census block because they interact very locally when exchanging information about jobs, even when one controls for personal characteristics.29 Consistent with sociological field evidence above, interactions are stronger between individuals who share a common education.30

Evidence also suggests that the social networks established in disadvantaged US neighborhoods may be so influential that they are difficult to break even after people move away. Xavier de Souza Briggs examined the social networks of black and Hispanic youth who participated in a court-ordered scattered-site public housing desegregation program in Yonkers, New York, during the 1990s.31 He found few differences in the network diversity or types of aid provided through networks between youth who moved to developments in white middle-class neighborhoods and those who remained in traditional public housing in poor, segregated neighborhoods. The former group did not leverage any benefits of living in more affluent and racially diverse areas, and their social ties typically remained within the common race and class confines of their scattered-site developments. Other studies found that families participating in the Moving to Opportunity demonstration in Chicago were likely to maintain close social ties with their former poverty-stricken neighborhoods even after they moved a considerable distance away to low-poverty neighborhoods.32 More than half of those families indicated that their social networks were located somewhere other than their new neighborhood.

A large number of US-based field studies provide a complementary view. They consistently show that the social interaction among members of different economic groups is quite limited, even within the same neighborhood or housing complex.33 Members of the lower-status group often do not take advantage of propinquity to broaden their “weak ties” and enhance the resource-producing potential of their networks, instead often restricting their networks to nearby members of their own group.

Social cohesion and control. In a number of studies, Robert Sampson and his colleagues emphasize the importance of the social control mechanism.34 To understand the effects of disadvantaged neighborhoods, they argue, one must understand their degree of social organization, which entails the context of community norms, values, and structures enveloping residents’ behaviors—what Sampson has labeled “collective efficacy.” Sampson’s work has empirically demonstrated that disorder and lack of social cohesion are associated with greater incidence of mental distress and criminality in neighborhoods.35 There also has been work suggesting that social control and disorder potentially have effects on an array of youth outcomes.36

Finally, Anna Santiago and I provide a unique perspective on the issue by asking low-income parents what they thought the main mechanisms of neighborhood effects upon their children were.37 The dominant plurality (24 percent) cited lack of norms and collective efficacy. By contrast, they cited peers (12 percent), exposure to violence (11 percent), and institutional resources (3 percent) much less often. Of interest is that one-third reported that their neighborhoods had no effect, either because their children were too young or because they thought they could buffer the impacts.

Competition and relative deprivation. The US statistical evidence (already cited) overwhelmingly suggests that affluent residents convey positive externalities to their less well-off neighbors in most outcome domains; in the realm of secondary education there is, however, cautionary evidence that more intensive competition from better-off students can produce some negative outcomes for lower-income students.38 The qualitative evidence is inconsistent, with some case studies indicating that upper-income gentrifiers can sometimes mobilize and compete in ways that can work to the detriment of the original lower-income residents.39

Parental mediation. Few would disagree that parents’ mental and physical health, coping skills, sensed efficacy, irritability, parenting styles, and sociopsychoeconomic resources loom large in how children develop. Thus, if any of the above elements are seriously affected by the neighborhood, by whatever causal mechanism, child outcomes are likely to be affected—though in this case the neighborhood effect for children is indirect.40 For example, as I will explore in the following section, certain neighborhoods expose parents to much higher stress, which in turn adversely affects children.41 Such neighborhoods may also vary, however, in their degrees of social support that might serve to defuse the negative effects of stress. As another example, parenting styles related to responsiveness and warmth and to harshness and control vary across aspects of neighborhood disadvantage.42 Such variations, in turn, are associated with adolescent boys’ psychological distress, among other outcomes.43 Finally, riskier neighborhoods are associated with lower-quality home learning environments in many dimensions, thus resulting in lower reading abilities, verbal skills, and internalizing behavior scores.44

Evidence on Environmental Mechanisms of Neighborhood Effects

Social scientists have extensively studied exposure to violence as an environmental effect mechanism. The Yonkers (New York) Family and Community Survey and Moving to Opportunity demonstration have strongly supported the importance of this factor as perceived by parents, since most public-housing families cited safety concerns as a prime reason for participating in these programs.45 One of the most significant results of the Moving to Opportunity demonstration was the substantial stress reduction and other psychological benefits accrued by parents and children who moved from dangerous, high-poverty neighborhoods to safer ones.46 Other work has demonstrated that youths and adults exposed to violence as witnesses or victims suffer increased stress and decline in mental health.47 Exacerbated stress, in turn, can produce a variety of unhealthy stress-reduction behaviors such as smoking,48 and over the long term can reduce the efficacy of the body’s immune system.49 Studies also have linked exposure to violence with aggressive behaviors and reduced social cognition, though these relationships appear to be substantially mediated by the stress levels of parents.50

Researchers have highlighted the negative health impacts of several aspects of the physical environment of the neighborhood, such as deteriorated housing51 and ambient noise levels.52 Others have argued that the physical design of neighborhoods (absence of sidewalks, local land use mixes, cul-de-sacs, etc.) can affect the amount of exercise that residents get, which in turn affects obesity rates and other health outcomes.53 Results from the Moving to Opportunity demonstration found that those moving from disadvantaged to low-poverty neighborhoods had reduced rates of obesity, which supports the view that some unspecified physical features of the neighborhood environment were at play.54

Finally, a variety of toxic pollutants potentially present in a neighborhood can generate a variety of physiological responses that impair the health of residents.55 As illustrations of how widespread these health consequences can be, epidemiological studies have identified strong associations between air pollutants and lower life expectancy, higher infant and adult mortality risks, more hospital visits, poorer birth outcomes, and asthma.56 Air pollution has been shown to degrade students’ performance on examinations and, over the longer term, lower their postsecondary educational attainments and earnings.57 Proximity to hazardous waste (“brownfield”) sites has been associated with higher rates of mortality from cancer and other diseases.58 Studies have demonstrated that even small amounts of lead poisoning (typically produced by residue from deteriorated lead-based paint formerly used in homes or in nearby industrial sites) produces harms to infants and older children in the realms of mental development, IQ, and behaviors.59

Evidence on Geographical Mechanisms of Neighborhood Effects

Numerous studies have investigated the issue of racial differentials in accessibility to work (the “spatial mismatch” hypothesis).60 Ethnographies have shown that low-income youths can benefit greatly from part-time employment (by gaining resources, adult supervision, and routinized schedules), yet their neighborhoods typically have few such jobs.61 Nevertheless, there is considerable statistical evidence that this spatial mismatch is of less importance to economic outcomes in most metropolitan areas than the social-interactive dimensions of neighborhoods.62

Evidence on Institutional Mechanisms of Neighborhood Effects

Many studies have documented the vast differences in both public and private institutional resources serving different neighborhoods.63 Though there has been considerable debate on this subject, the current consensus seems to be that measurable educational resources and several aspects of student performance are highly correlated.64 Shortages of high-quality child care facilities are acute in many low-income neighborhoods, despite their proven effectiveness in building a variety of intellectual and behavioral skills in young children.65 Lower-income communities are also at a disadvantage in terms of access to medical facilities and practitioners.66 Still other studies have shown how the internal workings of institutions serving poor communities shape expectations and life chances of their clientele.67 Moreover, it is clear that many low-income parents believe that a paucity of local resources can adversely affect their children,68 and often try to compensate for this lack by seeking such resources outside their neighborhoods.69

There is also substantial evidence regarding the large spatial variations in many sorts of market actors whose proximity may affect health-related behaviors of neighborhood residents. Several studies, for example, have documented distinctive race and class patterns in the locations of supermarkets70 and liquor outlets.71 Quantifying a convincing causal link between such contextual variations and individuals’ diets, consumption patterns, and health has proven more challenging, however.72 In a similar vein, several qualitative studies have recounted incidences of place-based stigmatization of areas; but it is difficult to quantify the extent and power of this mechanism, because scholars have not yet related it statistically to individual outcomes.73

A Synthesis Regarding Evidence on Neighborhood Effect Mechanisms

What does the foregoing evidence suggest about the relative importance of various neighborhood effect mechanisms? With the mandatory caveat that firm conclusions are elusive here due to the underdeveloped state of scholarship and the complexity of the topic, my evaluation provisionally suggests the following nine conclusions.

First, research has consistently linked high concentrations of poverty (which typically are heavily Hispanic-occupied and especially black-occupied neighborhoods) statistically to weaker neighborhood cohesion and structures of informal social control. This situation is associated, in turn, with negative consequences like increased youth delinquency, criminality, and mental distress, although scholars have not yet linked it to other important outcomes like labor market performance. In this research, however, the aforementioned concentrations of poverty retain their relationship with a variety of child and adult outcomes even after intraneighborhood levels of social control and cohesion are taken into account. Clearly, more than this mechanism is at work.

Second, the fact that neighborhood poverty rates appear consistently related to a range of outcomes in a nonlinear thresholdlike fashion further suggests that the social contagion (peers) or the collective socialization (roles models, norms) forms of causal linkage are transpiring. There may also be some selectivity involved, as some socially disadvantaged groups seem more vulnerable to these contexts than are advantaged ones. I do not believe that the evidence can clearly distinguish the respective contributions made by the latter two alternatives.74

Third, the presence of affluent neighbors appears to provide positive externalities to their less well-off neighbors, seemingly working via the mechanism of social controls and collective socialization. Social networks and peer influences between the affluent and the poor, by contrast, do not appear as important in this vein. The outcomes for individuals that are most strongly related to affluent neighbors seem to be different from those most strongly related to disadvantaged neighbors. There is consistent evidence to suggest thresholds here as well, though the precise threshold is unclear and likely varies by outcome under consideration. Finally, most evidence indicates that the influence on vulnerable individuals of advantaged neighbors is smaller in absolute value than the influence of disadvantaged neighbors, whatever the mechanisms at play.

Fourth, there is little evidence suggesting that the competition or relative deprivation mechanisms operate in a meaningful way for lower-income individuals, with the possible exception of the secondary education domain.

Fifth, studies have consistently found relatively little social networking between lower-income and higher-income households or children within a given neighborhood, and this lack is compounded if racial differences are involved. Thus, there is little to support the version of neighborhood effects in which advantaged neighbors create valuable “weak ties” for disadvantaged ones.

Sixth, local environmental differences appear substantial, and likely produce important differentials in mental and physical health. Exposure to environmental pollutants and violence has the clearest consequences for the health of children, youths, and adults. Scholars have not adequately explored the longer-term consequences of these health impacts on educational, behavioral, and economic outcomes.

Seventh, it is unclear how much geographic disparities related to accessibility to work play an important role in explaining individual labor force and educational outcomes in all metropolitan areas.

Eighth, differences undoubtedly exist in in local institutional quality (especially related to public education), and local market actors. Unfortunately, convincing statistical models of the relationship between measured variations in these potential institutional causal mechanisms and a wide range of individual outcomes are rare.

Finally, there is probably a substantial indirect effect on children and youth that transpires through the combined effects of the social-interactive, environmental, geographic, and institutional dimensions of the neighborhood context on their parents. This is likely to affect a broad range of outcomes, though there have been no attempts to measure them comprehensively.

In sum, it is most sensible to conclude that many sorts of neighborhood effects are in operation simultaneously, but their relative importance is contingent on the particulars of the situation. Which mechanism dominates likely depends on the domain of outcome in question, and on the age, gender, and economic resources of the individuals under investigation.75

Evidence on the Magnitude of Neighborhood Effects on Socioeconomic Outcomes

Obtaining unbiased, meaningful estimates of the independent, causal effect of an individual’s neighborhood context is a notoriously challenging enterprise.76 Perhaps the most contentious aspect in this realm of scholarship, however, is the issue of geographic selection bias.77 The central issue here is that individuals or their parents typically move from and to certain types of places with an aim of improving their household’s prospects. Researchers can readily measure, and thus statistically control, many of these household predictors of residential choices, as I discussed in chapter 1. Concerns arise, however, because households likely have unmeasured motivations, behaviors, and skills related to their own socioeconomic prospects or those of their children, and make neighborhood selections as a consequence of these unobserved characteristics that by definition cannot be statistically controlled by researchers. Any observed relationship between neighborhood conditions and outcomes for adults or their offspring may be biased because of this systematic spatial selection process.78 Skeptics may rightly argue that unmeasured individual attributes drive the observed relationship, not the independent causal impact of the neighborhood in which the individual resides.

Three Approaches to Estimating Causal Impacts of Spatial Context

There have been three general empirical approaches adopted in response to the challenge of geographic selection bias. The most common approach consists of a variety of econometric techniques applied to observational (non–experimentally generated) longitudinal datasets involving individuals and their spatial contexts. The two other, less common approaches use natural or experimental designs to generate quasi-random or random assignments of households to neighborhoods.

Econometric models based on observational data. Most studies of spatial context effects have used observational data collected from surveys or administrative records of individual households residing in a variety of places because of mundane mobility factors associated with normal housing market transactions. The subset of studies that has tried to overcome geographic selection bias employs one or more of the following approaches:79

- • Difference models based on longitudinal data: Measuring differences between two periods in both outcomes and spatial contexts reduces the biases from unobserved, time-invariant individual characteristics.80

- • Fixed-effect models based on longitudinal data: Dummy variables for each individual observation serve as proxies for all unobserved, time-invariant characteristics of individuals that may lead to both geographic selection and outcomes.81

- • Instrumental variables for spatial context characteristics: The researcher devises proxy variables for geographic characteristics under investigation that, though correlated with these characteristics, only vary according to attributes exogenous to the individual, and thus are uncorrelated with their unobserved characteristics.82

- • Residents of same block: If little sorting on individual unobserved characteristics occurs at the census block level, then the impacts of networks among these very localized neighbors should be free of geographic selection bias.83

- • Timing of events: Individuals moving into certain well-defined places (such as public housing developments) after an event being investigated (such as a school achievement test) are likely to share common unobservable characteristics with individuals moving into the same places just before the event, so the short-term effect of the place can be measured by comparing the two groups’ outcomes.84 Analogously, one can address the selection bias problem by exploiting the variation in the timing of discrete neighborhood events compared to interview assessments for a sample of children in families that have previously selected the same neighborhood.85

- • Propensity score matching: Individuals who are closely matched on a wide variety of observable characteristics that predict their similar residential mobility behavior are likely to be well-matched on their unobservable characteristics as well; comparisons between matches of differences in their spatial contexts and individual outcomes should thus provide unbiased causal evidence.86

- • Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW): Like propensity score matching, IPTW uses a model of selection into the treatment status to predict the probability that an individual is in the observed treatment state. The investigator then constructs a weighted pseudosample in which the treatment and control groups are balanced on as many observable characteristics as possible. IPTW models selection into treatment status at multiple time points, allowing for unbiased estimates of treatment effects over time in the presence of observed confounders that vary over time and may be endogenous to the treatment.87

- • Nonmovers: Analyzing how exogenous neighborhood changes induce different outcomes for individuals who do not move during the analysis period arguably avoids part of the mobility selection issue.88

- • Sibling comparisons: Researchers can reduce biases from unobserved, time-invariant parental characteristics by measuring differences in outcomes and neighborhood experiences between siblings, who presumably are affected by the same set of unmeasured household characteristics.89

None of these econometric fixes to observational datasets is without challenge. As illustration, difference models reduce statistical power by shrinking variation in the outcome variable, and they assume that change relationships are independent of starting conditions. Fixed-effect models assume that the individual dummies adequately capture the bundle of unobserved characteristics for all times during the panel, and that the effect of this bundle remains constant during the panel. Instrumental variables must be both valid and strong, requirements that are not easily met. Microscale investigations are limited to neighborhood effect mechanisms than operate only at the small geographic scales, and they assume that there is no residential sorting on unobserved characteristics at that scale. Relying on the timing of moves immediately before and after an event assumes that context effects operate quickly after exposure. Propensity score matching and IPTW require assumptions about the strong relationship between unobservable and observable characteristics of individuals. Those individuals who do not move may be exhibiting residential selection based on unobserved characteristics. Variations in neighborhood exposures across siblings may be minimal, thus eroding statistical power.

Quasirandom assignment natural experiments. It is sometimes possible to observe nonmarket interventions into households’ residential locations that mimic random assignment. In the United States, such experiments typically have been based on court-ordered public housing racial desegregation programs,90 regional fair-share housing requirements,91 or scattered-site public housing assignments.92 In Canada and Europe, they have involved allocation of tenants to social housing,93 or placement of refugees in particular locales.94

Although these natural experiments may indeed provide some exogenous variation in locations, researchers are unlikely to avoid the geographic selection problem completely. In most cases, program staff makes assignments, and participants have some nontrivial latitude in which locations they choose, both initially and subsequent to original placement. Moreover, if the programs involve the use of rental vouchers, there will be selectivity in who succeeds in locating rental vacancies in qualifying locations, and in signing leases within the requisite period. These various potential selection processes raise the possibility that low-income families who succeed in living persistently in low-poverty neighborhoods have been especially motivated, resourceful, and perhaps courageous—traits measured poorly by researchers, but which likely would help the families succeed irrespective of their spatial contexts. Additional empirical problems can arise if sampled subjects move quickly from their quasirandomly assigned dwellings to other locations, thereby minimizing their exposure to measured context, and potentially confounding consequences because moving itself can be disruptive. As time passes, the randomness of location can erode, as selection of who stays in initially assigned places and who moves away comes into play. Finally, there may limitations in the range of places to which study participants move or are assigned, because of the location of available private rental or subsidized housing, thereby reducing the power of statistical tests to discern context effects.

Random assignment experiments. Many researchers advocate a random assignment experimental approach for best avoiding biases from geographic selection. Producing data on outcomes by an experimental design whereby individuals or households are randomly assigned to different geographic contexts is, in theory, the preferred method. In this regard, the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration has been touted conventionally as the study from which to draw conclusions about the magnitude of neighborhood effects.95 The MTO research design randomly assigned public housing residents who volunteered to participate in one of three groups: (1) controls that got no voucher but stayed in public housing in disadvantaged neighborhoods, (2) recipients of rental vouchers with no restrictions, and (3) recipients of rental vouchers and relocation assistance who had to move to census tracts with less than 10 percent poverty rates and remain there for at least a year.

There has been substantial debate over the power of MTO as an unambiguous test of spatial context effects.96 The debate focuses on five domains. First, although MTO randomly assigned participants to treatment groups, it randomly assigned neither characteristics of neighborhoods initially occupied by voucher-holders (except maximum poverty rates for the experimental group) nor characteristics of neighborhoods in which participants in all three groups later moved. Thus, there remains considerable question about the degree to which geographic selection based on unobserved characteristics persists. Second, MTO may not have exposed any group to neighborhood conditions long enough to observe much effect. Third, MTO overlooked the potentially long-lasting and indelible developmental effects upon adult experimental group participants who spent their childhoods in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Fourth, it appears that even experimental MTO movers rarely moved out of predominantly black-occupied neighborhoods near those of concentrated disadvantage, and achieved only modest changes in school quality and job accessibility. Thus, they may not have experienced sizable enhancements in their geographic opportunity structures. For these reasons, MTO may not have provided definitive evidence about the potential effects on low-income minority families from prolonged residence in multiply advantaged neighborhoods, despite its theoretical promise and notwithstanding conventional wisdom.

In summary, none of the three broad approaches to measuring effects of spatial context has proven limitation-free and unambiguously superior. Nevertheless, they as a group offer the strongest plausibly causal evidence to date on the topic at hand. Therefore, in the review that follows I will synthesize findings only from these methodologically rigorous studies that employ one or more of the aforementioned approaches.

A Synthesis of the Scientific Literature on Neighborhood Effects on Individuals

I organize the review by outcome domains that are closely related to socioeconomic opportunity: (1) risky behaviors, (2) cognitive skills and academic performance, (3) teen fertility, (4) physical and mental health, (5) labor force participation and earnings, and (6) crime.97 I emphasize at the outset that the scope, diversity, and complexity of the relevant literature is vast, so I limit my synthesis to only those studies that employ one of the aforementioned techniques for producing estimates of plausibly causal effects. Moreover, I do not attempt to review findings in any detail, reconcile conflicting results, nor attempt any formal meta-analysis. Instead, my aim is basic: in each outcome domain I will tally the number of these methodologically rigorous studies that find substantial, statistically significant effects of at least some aspect of spatial context (for at least some set of individuals) and those that do not.

Risky behaviors. As for risky behaviors, six studies of context effects involving the aforementioned econometric approaches to overcoming geographic selection have been undertaken, and most identified effects on a variety of risky behaviors.98 There are two examples of either the random or quasirandom neighborhood assignment approaches relevant to risky behaviors. Strong context effects on risky behaviors appear in both studies, but they are contingent on gender, ethnicity, and timing. Early MTO findings suggested that residence in lower-poverty neighborhoods led to substantial reductions of girls’ rates of risky behaviors and boys’ drug use. However, after initial declines in risky behavior, boys living in lower-poverty neighborhoods four to seven years after their first move were more likely to reengage in risky behaviors.99 By the end of the demonstration project, girls assigned to low-poverty neighborhoods were less likely to have serious behavioral problems. There were no significant group differences in more serious antisocial behaviors, however. Anna Santiago and colleagues’ analysis of data from a Denver natural experiment revealed that cumulative exposure to multiple dimensions of neighborhood context (especially safety, social status, and ethnic and nativity composition) affected the hazard of adolescents running away from home, using aggressive or violent behavior, or initiating marijuana use, though with substantial ethnic heterogeneity of relationships.100

Cognitive skills and Academic Performance. A recent meta-analysis of the international literature and a comprehensive review of the US literature conclude that there are nontrivial neighborhood effects on the development of cognitive skills, academic performance, and educational attainment.101 My assessment of the methodologically sophisticated literature reaches a similar conclusion, though I hasten to note that the magnitude of the neighborhood effect likely varies across individuals and groups.