ONE

Introduction

Virtually everyone in the United States has grown up or lived in what they would consider a neighborhood. Despite this intimate familiarity, most people have little understanding of the forces that bring neighborhoods into being and make them change, the many ways in which neighborhoods influence our lives, whether these neighborhood-related processes are good or bad for society, and how we might intervene with public policies if we think neighborhood outcomes should be improved. In this book, I shed light on all these dimensions. To use a medical metaphor wherein the neighborhood is the “patient,” this book develops principles for comprehending the etiology of disease, diagnosing the patient, assessing the disease’s consequences for the patient, and providing an efficacious prescription.

More specifically, in this book I address in a holistic, multidisciplinary way the fundamental questions regarding neighborhoods by marshaling a half century worth of theory and evidence from many social sciences. What is the neighborhood? What drives changes in its residents’ economic standing or racial/ethnic composition, physical conditions, and retail activities? How do households and property owners form expectations about neighborhood change and interact with each other? What are the idiosyncrasies of neighborhood change processes? What consequences for human and financial capital transpire when neighborhoods change, and who disproportionately bears the costs of such changes? Why do we have so many blighted neighborhoods and ones that evince little diversity on racial/ethnic or economic grounds? In what dimensions and through what mechanisms do neighborhoods affect their residents? Is the current constellation of American neighborhoods optimal from society-wide perspectives of efficiency and equity? In addressing these questions, I derive eight summary propositions. Based on this diagnostic analysis, I then advance public policy and planning prescriptions for dealing with three most significant problems associated with how we have made our neighborhoods: physical blight, economic segregation, and racial/ethnic segregation.

The Framing of This Book

I ground my analysis on two premises that jointly provide a holistic perspective on neighborhoods.1 First, the nature and dynamics of the phenomenon we call the neighborhood result from the aggregation of individual behaviors driven primarily by two sets of actors—household occupants and owners/developers of residential property—operating within the framework of price signals and constraints provided by a predominantly capitalistic housing market operating at the metropolitan scale. Second, the character and dynamics of the neighborhood, in turn, affect a wide range of perceptions, behaviors, dimensions of well-being and socioeconomic opportunities of its resident adults and children. Put more succinctly, we make our neighborhoods and then they make us.2

In the next two sections, I provide overarching frameworks for these premises. I first focus on the determinants of individual household residential mobility, tenure choice, and residential property investment decisions, synthesizing the existing scholarship on these behaviors. Then I focus on how these two sets of decision makers are behaviorally linked, how their actions get aggregated to produce neighborhood-level outcomes, and how these aggregate outcomes in turn reflect back on the individual decision makers and their families, shaping their perceptions, behaviors, quality of life, and future opportunities. My frameworks are distinguished by their consideration of different spatial scales—individual, neighborhood, local political jurisdiction, and metropolitan area—and how the forces affecting neighborhoods are woven together in a complex web of mutually causal, self-reinforcing relationships.

Making Neighborhoods: Individual Decisions about Residential Mobility, Tenure Choice, and Property Investments

My unified framework for understanding the household’s residential mobility and tenure choice behavior and the dwelling owner’s investment behavior—the fundamental building blocks of neighborhood change—is represented diagrammatically in figure 1.1. In this and succeeding figures, rectangles denote sets of characteristics, attitudes, expectations, and behaviors, and presumed causal linkages between them are shown as arrows or “paths.” In this part of the analysis, for simplicity I consider the stock of existing households, dwellings, and neighborhoods to be predetermined for the decision maker. Though expectations about future changes in existing and new neighborhoods are an essential part of the decision-making process, as I will amplify below, for the most part during the short period when households and property owners are actively deciding where to live, whether to own or rent, and how much to invest in properties, they take the current array of opportunities as essentially fixed. I will consider the longer-term decisions about adding to the housing stock via construction of new properties and rehabilitation of nonresidential properties later in this chapter, and especially in chapter 3.

Figure 1.1. The objective and subjective determinants of individual household residential mobility, tenure, and property investment behaviors

During some short-term “snapshot” period of observation, the objective characteristics of the individual, the current dwelling occupied, the current neighborhood (including interactions with neighbors), prospective dwellings and neighborhoods, and any relevant private or public investments or policies supplying resources to the neighborhood can be considered predetermined—that is, taken as fixed values by the individual decision maker. Based on these currently experienced objective characteristics, the individual will form perceptions, mold beliefs, make subjective evaluations of the current dwelling and neighborhood (perhaps in relation to alternatives), and develop expectations about the future of the neighborhood.3 Based on these objective characteristics and subjective perceptions, beliefs, evaluations, and expectations, the resident household will make a decision about remaining in the current location or moving, in combination with a closely related decision about whether to own or rent the occupied property. Based on analogous inputs, the owner of the dwelling under consideration (who might be the occupying household) will make a decision about whether to sell the property; hold it and either maintain, undermaintain, or improve its quality; or (in the extreme) abandon the property. In the case of owner-occupiers, these latter decisions must be made jointly.4

In sum, my framing posits that several distinct sets of objective characteristics of the individual and the context influence several subjective attributes of the individual. Together these objective, predetermined elements and subjective, “intervening” elements determine individual residential mobility, tenure choice and/or housing investment behavior. The causal impacts of objective individual and contextual characteristics upon these two decisions may be direct and/or indirect; that is, mediated to greater or lesser degree by the intervening subjective elements. Consider now in more detail in the next two subsections what comprises these various elements and how they may be interrelated in the context of received scholarship about residential mobility, tenure choice, and housing reinvestment behaviors.

Residential Mobility Behavior of Households

Five theories of voluntary5 intraurban residential mobility have competed in the scholarly literature for decades, though they typically share many features and the lines among them are often blurred.6 As I will demonstrate, the causal paths in figure 1.1 it views as predominant distinguish each theory.

The first, “life course” theory, posits that households move in a predictable pattern across their lifetimes.7 Households evaluate their current residential situations in light of their current shelter needs associated with their particular stages in life: single, married without children, married with young children, married with older children, and so on. They typically deem the status quo no longer suitable when a new life stage emerges, whereupon mobility transpires. Features and size of the dwelling are often crucial in these situations, neighborhood context less so, from the perspective of life course theory. This theory sees paths E and B/D-R in figure 1.1 as salient.

The second, the “stress” theory, takes the view that households assess whether to move by comparing the satisfaction associated with current and potential residential environments.8 Stress is defined as the difference between current and potential residential satisfaction, and is seen as being directly related to the probability of moving. Life-cycle transitions can generate stress, but so too can neighborhood conditions such as intolerable socioeconomic composition or racial transition. This theory expands the hypothesized salient paths in figure 1.1 to include not only those above in the “life course” theory, but also F/I/K-S.

The third perspective, the “dissatisfaction” theory, posits that mobility is a two-stage process that begins when a threshold of dissatisfaction is exceeded.9 During the initial stage, households evaluate salient aspects of the current residential environment (potentially including those associated with both dwelling and neighborhood) in light of their needs and aspirations, yielding a certain high or low absolute degree of “residential dissatisfaction.” If the household registers sufficient dissatisfaction, it will develop a desire to move and enters into the second stage of the process, which involves actively gathering information to assess alternative residential locations. The members of the household will make the decision to move if they can find a financially feasible alternative that prospectively offers some relief from their dissatisfaction. In this view, background characteristics of both the household and the residential context influence mobility desires and actions only through the intervening variable of the current absolute level of residential dissatisfaction; that is, only paths B/D-R and F/I/K-S in figure 1.1.

The fourth theory, “disequilibrium,” posits that households attempt to maximize their well-being by consuming an “optimal” bundle of residential (dwelling and neighborhood) attributes.10 At any moment, however, households may not reside in their optimal bundle (i.e., be in disequilibrium) because family or current residential circumstances may have changed since the original point of in-moving or because other, superior market opportunities may have arisen subsequently. The probability of moving out is directly related to the degree of such disequilibrium between the households’ current and prospective feasible residential options, and inversely related to housing market search and moving costs. Market search will be undertaken whenever the expected benefits (marginal gain in well-being) of locating a more optimal, feasible alternative exceed the expected search costs. Although the marginal expected benefits of mobility are directly related to the current degree of disequilibrium residential consumption, there is no implicit threshold of absolute disequilibrium involved. Nevertheless, the salient paths in figure 1.1 would still be B/D-R and F/I/K-S.

In the fifth approach, “perceived net advantage,” I synthesized aspects of the above theories and extended from them by drawing from behavioral psychology to include the role of future expectations.11 At any particular moment, households may be seen as holding a multifaceted set of beliefs that inform a potential mobility decision, which concern both current and future (1) household needs and aspirations, (2) dwelling and neighborhood characteristics of occupied location and feasible alternative locations, and (3) financial and other adjustment costs associated with moving. Contemporary and futuristic beliefs are influenced not only by active market search but by passively acquired information gained through commuting, mass media, conversations, and so on.12 Taking into account beliefs about its current and anticipated needs and aspirations, the household will comparatively evaluate which feasible alternative locations (both now and in the future) may best meet them over an extended time horizon. Mobility will be triggered when a feasible alternative evinces a prospective long-term advantage in fulfilling needs/aspirations (net of adjustment costs), as appropriately adjusted for uncertainty and time horizons. From the perspective of the perceived net advantage theory all direct and mediated causal paths to mobility shown in figure 1.1 are of potential salience.

One common implication of all these approaches to residential mobility, with the possible exception of the “life course,” is that undesirable changes in the current neighborhood should increase the propensity to move out.13 Many multivariate statistical studies have supported this implication by identifying several objective neighborhood indicators as robust predictors of greater mobility. These have included increasing crime and declining neighborhood physical quality,14 lower homeownership rates,15 higher (and growing) percentages of black neighbors16 or lower-income neighbors,17 and greater discrepancies between the household’s income and that of the rest of the neighborhood.18 Perceptions of disorder can also prove a powerful stimulant to moving out.19

Of equivalent importance for the analysis in this book, characteristics of the neighborhoods from which households may feasibly choose, not just those of the prospective individual dwelling, influence the choice of where a household moves once it decides to leave its current neighborhood. Opinion polls have found that most Americans prefer the option of an inferior dwelling located in a better neighborhood than an equally expensive option involving a superior house in an inferior neighborhood.20 Researchers have found that when households are considering new potential neighborhoods, they most often are attracted to those having kin and friends,21 predominantly residents of similar economic standing22 and those of the same race or ethnicity.23

Housing Tenure Choice

There is much less theoretical dissention about the underlying factors that households weigh when considering whether to own or rent the dwellings they occupy.24 The household first considers the financial resources available for the purchase of a home or the successful application for a mortgage: long-term (“permanent”) income, assets, debt, credit rating (path E in figure 1.1). Then the prospective buyer must weigh the potential ongoing costs of holding the properties of the type, size, location, and features that are financially feasible. These costs include structural improvements, maintenance and repairs, local property taxes, federal income taxes (treatment of local tax and mortgage interest deductibility), hazard insurance, and expected equity appreciation (both for the home in question and for investments in alternative financial instruments); see path Q in figure 1.1. Finally, the household must assess the nonfinancial dimensions of homeowning: the value it places on independent control of the property and its terms of occupancy (path E in figure 1.1).

What should be clear from the foregoing summary of the tenure choice process is that it is inextricably bound up with mobility and neighborhood expectations.25 The decision maker must project the length of stay in the dwelling being considered for purchase. It is usually sensible to incur the considerable out-of-pocket and time costs associated with home purchase only if the household plans to remain there for a number of years. Moreover, the expected duration of residency may influence the expected home equity appreciation. Due to this joint nature of the choice between residential mobility and tenure, I portray them in the same box in figure 1.1.

It also should be clear that neighborhood perceptions, evaluations, and expectations strongly influence the tenure choice process (paths R, S, and T in figure 1.1). If the only homes a household can afford are located in weak, declining neighborhoods, for example, households may forego homeowning because they perceive that it will tie them to an unsatisfactory quality of residential life, and will expect the appreciation of their property to be minimal. Alternatively, households in certain segments of the housing market may perceive that few rental options exist in desirable neighborhoods, whereupon their desires to buy a home will receive a boost. This shaping of whether we rent or buy property is one of a number of ways in which neighborhood affects us, a persistent theme that will be illustrated throughout this book.

Housing Investment Behavior by Owners

At any particular moment, the investment options faced by owners of existing dwellings are threefold: improve the quality of the structure, maintain quality at the current level, or allow quality to decline (either by passive undermaintaining or by active partitioning of the dwelling into one or more smaller units). Once an owner chooses the strategy, an amount of investment can be decided upon. The predominant theory of such decision making on the part of investors of residential properties presumes that they are motivated to choose in such a way that their expected financial rate of return is satisfactory (at least, if not maximized) compared to nonhousing investment alternatives, considering to some degree both immediate and future financial flows.26

The intertemporal nature of the housing investment decision and the durability of the investment once made focus attention on the central role played by the owner’s expectations. Expectations about the future costs for housing improvements, the rate of structural depreciation, the interest rate for borrowed funds (i.e., the opportunity cost of savings), conditions in the surrounding neighborhood, and the rate of housing-price inflation jointly affect the perceived returns gained from expenditures on housing. All these expectations shape the owner’s net operating income from the dwelling being occupied and its asset value when it is eventually sold. In the context of figure 1.1, direct paths A, C, H, Q and indirect paths F/I/O–W and G/J/P–U are relevant for the owner of residential property. Consider these causal influences in more detail.

Influences on owner’s investment behaviors. Characteristics of the dwelling in question are independent, direct contributors to the observed housing investment behaviors (path A). Older structures usually deteriorate at a faster rate, thus presenting the owner with more frequently needed repairs to maintain constant quality. Dwellings with particular structural features render certain structural modifications extremely expensive; for example, those with sagging foundations are unlikely to support the addition of a second-story dormer, and those with obsolete wiring may not permit the installation of modern appliances or heating and cooling systems. A small lot may preclude the addition of a detached garage or a swimming pool. But beyond their physical features, dwellings may take on subjective and symbolic meanings for their owners that ultimate shape the sorts of investments that are made in them (path B-X).

Characteristics of the homeowner also directly influence the type of home investment strategy chosen and the expenditures allocated to its pursuit (path C). For example, owners with access to inexpensive yet skilled labor (perhaps their own) likely perceive home maintenance and repair costs as relatively low. The nature of the information one acquires shapes perceptions and expectations, of course; and the methods and extent of data acquisition vary by education, income, age, and family status of the owner (paths D-X, F-W, and G-U).27

The physical, demographic and socioeconomic character of the neighborhood in which a particular dwelling is located powerfully influences the type of investment strategies pursued. The value of the dwelling is not determined merely by its features and the lot on which it is located, but also by the surrounding environs’ socioeconomic, racial, ethnic, age, and family-status composition, environmental amenities, local public-service and infrastructure quality, land-use patterns, and aggregate housing stock conditions (path H).28 This means that the owner’s perceived payoffs from incremental investments will depend on the current as well as future conditions of the surrounding neighborhood that are capitalized by the market (path I-W). These physical, demographic, and socioeconomic attributes of the neighborhood also provide clues to prospective changes in the milieu (path J-U).29

Finally, resources provided by the nonprofit and for-profit sectors may impinge on the owner’s upkeep calculus. Governments, for instance, may directly subsidize housing repairs and improvements by providing grants or low-interest loans for this purpose (path Q). More indirectly, the actions of the public sector can greatly influence the perceptions and expectations held by owners, and thereby their subsequent investment activities (paths O-W and P-U). These actions may be substantive or symbolic. Examples of the former include improving neighborhood public parks, streets, lighting, or schools; encouraging the formation of local neighborhood organizations; or rezoning the area to permit or prohibit nonresidential land uses. Illustrations of the latter include the formation of a mayor’s neighborhood advisory board with appointees from all neighborhoods, the designation of an official neighborhood X pride week, or the erection of signs proclaiming the boundaries, name, and history of each neighborhood. The for-profit sector, especially the local retail sector, can also have substantial influences on the attractiveness of a neighborhood, and thereby on the investment incentives of property owners.

Additional influences on owner-occupant’s investment behaviors. Additional factors come into play for the property owner who also is the occupant. In such cases, the investment decision typically involves both “consumption” and “investment” dimensions.30 First, maintaining or improving structural quality may be seen as increasing “utility” or well-being gained from consuming (i.e., living in) the dwelling, but it requires a sacrifice of income that could be spent otherwise. Reducing housing quality, on the other hand, sacrifices such housing-related utility but allows for greater consumption of other goods and services besides housing, especially if the generation of added income accompanies the quality decline. Such could be the case if an owner subdivided an erstwhile single-family dwelling to produce one or more rental properties. A second consideration likely for most homeowners is the wealth effect of such housing investment activity. If an owner placed importance on the value of the durable housing package as an asset beyond its current value as a consumer good, the calculus of the housing investment decision would be altered. In other words, spending money on one’s home can be considered an investment, because it increases the eventual sales price of the home, and thus the wealth and future consumption possibilities of the homeowner.

The homeowner’s decision is also related to time in a more complex way than is that of the absentee owner. The choice of housing versus nonhousing expenditures cannot be fully understood in the context of a single moment. Because housing is a durable good, spending on it currently produces a useful flow of housing-related consumption services, as well as an augmented asset value for several subsequent periods. The degree to which any particular housing investment provides continuing consumption and asset benefits in the future depends on the rate of structural depreciation, the homeowner’s rate of time preference, and changes in neighborhood conditions. The homeowner’s decision thus involves not only choosing the desired mix of housing and nonhousing expenditures in the current period, but also this desired pattern of spending in the current period versus future ones.

Implicit in this discussion of the intertemporal nature of housing investment decisions by owner-occupants is the closely related decision about mobility. Obviously, a homeowner can adjust the amount of housing consumed by moving to a different dwelling, typically in conjunction with selling the previous home. The homeowner thus will sometimes contrast the well-being gained from pursuing a particular investment strategy for the current dwelling with that which can be gained from moving to another dwelling, possibly in a different neighborhood. Having formulated expectations and mobility plans, the homeowner makes a choice of housing versus nonhousing expenditures over the expected duration of tenure in the dwelling, within the set of constraints formed by both financial limitations of the owner and structural limitations of the dwelling. The former limitations consist of initial wealth, expected household income flows, and institutionally imposed borrowing constraints (path C in figure 1.1). The latter consist of the various architectural and mechanical idiosyncrasies of the physical structure that render alternative dwelling modification schemes more or less feasible in terms of incremental housing value gain versus modification cost (path A). Compared to those who plan to stay in their dwelling for a considerable period, homeowners who plan to move in the near future would be less concerned about the long-run consequences of current upkeep activities. That is, they would not be present to reap much of the stream of enhanced housing consumption provided by current upkeep, and hence would be less likely to undertake sizable amounts of such (path V).

The neighborhood is, of course, more than simply a place having particular physical features where particular types of autonomous individuals reside and into which financial resources flow. It is also an arena in which social interaction typically occurs among neighbors: they make friends, encourage conformity to collective norms, formulate solidarity sentiments, and pass along information. Another important distinguishing feature of owner-occupants as opposed to absentee owners is that the former are directly subject to this social dimension of the neighborhood in which they invest; the latter are not. This means that collectively those in the neighborhood have at least a potential for influencing the home investment behavior of homeowners residing there (path N).31 This is the crucial distinction between owner-occupants and absentee owners that explains much of the observed differences in their housing investment actions.32

The social-interactive dimension of neighborhood may also have three indirect impacts on homeowners. First, social discourse among neighboring homeowners may provide a conduit for data sharing that tend to create common perceptions informing their investment decisions (path K-W). Second, it may reassure each individual owner that all the other homeowners in the neighborhood are likely responding to the same social pressures to maintain dwelling quality. Thus, homeowners in a neighborhood with a great deal of social cohesion may be more likely to be optimistic in their expectations (and in the market’s evaluation) of the neighborhood’s physical quality and property value projections (path M-U). Third, it may alter homeowners’ expected longevity of tenure. Homeowners who are more attached to their neighborhood by strong social ties are less inclined to rupture these connections by moving out of the neighborhood, all else equal (paths L-V).

Making Our Neighborhoods: Aggregating Individual Decisions into Neighborhood Outcomes

The foregoing discussion summarized in figure 1.1 was based on the premise that those who wish to understand neighborhood dynamics must first understand the behavior of individual households and dwelling owners who ultimately determine the aggregate neighborhood outcomes. One must realize, of course, that in a broader, intertemporal framework, individual behaviors and aggregate neighborhood outcomes are related via mutually causal connections. In other words, individual actions in one period determine overall neighborhood characteristics in the next period through straightforward aggregation; these in turn affect subsequent individual perceptions, behaviors, evaluations, expectations and qualities of life.33 Thus, not only do individual behaviors shape what neighborhoods are and how they change, but neighborhood conditions and stability affect individuals in turn, in a variety of powerful ways. Figure 1.2 illustrates this fundamental point about circular patterns of causation schematically.

At any particular moment summarized in figure 1.1, three factors will influence the decisions made by an individual (resident household and/or property owner) in the neighborhood under consideration. These include (1) the aggregate behaviors of other households and owners in the neighborhood (path B in figure 1.2); (2) the aggregate behaviors of other resource providers in the public and for-profit sectors (path A); and (3) the current and expected future aggregate conditions in the neighborhood (path C). The individual undertakes a mobility, tenure, or housing investment behavior in ways described in the previous section, in conjunction with his or her personal and dwelling characteristics (path G). Concurrent with this individual’s behavior, other households and property owners in the same neighborhood are also making mobility, tenure, and investment decisions (path F). Moreover, individual mortgage lenders, retail developers, and public policy makers are also making decisions that will affect the flow of resources into the particular neighborhood (path E). This welter of individual behavioral decisions will determine in aggregate what characteristics the neighborhood will exhibit in subsequent periods after the changes in residence and the real estate investments have come to fruition (paths E, F, and G). But if the aggregate characteristics that manifest themselves over time confound the original expectations held by the three sets of decision makers, further modifications of their behaviors likely will be generated (paths H, I, and C). Of course, such modifications of individual behaviors in turn may alter again the aggregate outcomes for the neighborhood, and the process of circular causation continues.

Figure 1.2. Individual behaviors and neighborhood outcomes: patterns of circular causation

Neighborhoods Making Our Selves

Thus far, I have only considered how neighborhood conditions shape the mobility and tenure decisions of residents and the dwelling investment decisions of owners of property in the neighborhood, as summarized in paths I and C in figure 1.2. Though these influences are undoubtedly powerful, they by no means represent the full extent of how our neighborhoods shape us. There are three additional pathways through neighborhoods exert their effects on us.

First, neighborhoods directly shape how and where we collect data about our world, how we evaluate it and how we translate it into information useful for our decision-making. I discuss this pathway of neighborhood effect at length in chapter 5. Second, neighborhoods directly impinge on our mental and physical health by specifying the contextual influences to which we are exposed. The impacts of local schools, pollution, and violence are obvious illustrations. Finally, neighborhoods indirectly affect the human attributes that we acquire during the course of our lifetime by molding what options we perceive as most desirable and feasible. In this way, neighborhoods affect our decisions in the realms of fertility, education, employment and illegal activities, and thus influence the courses of our lives. These last two pathways are the subject of chapter 8.

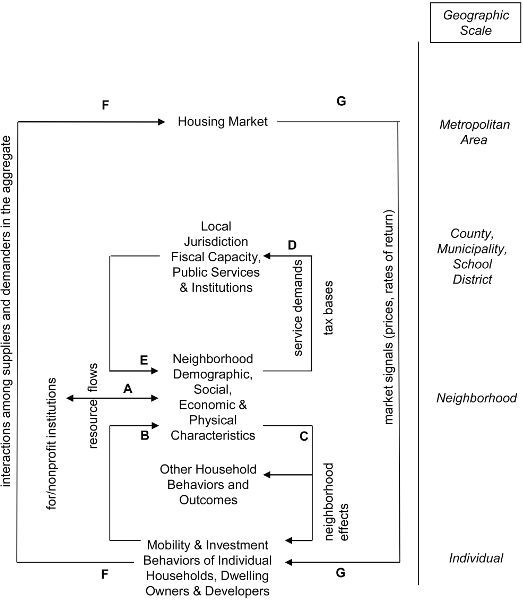

A Holistic, Multilevel, Circular Causation Model of Neighborhoods

Prior sections have stepped through the components of a holistic view of how we make our neighborhoods and how they make our selves. It is helpful to visualize these connections in a unified fashion; see figure 1.3. It makes clear my position that to understand the causes and effects of neighborhoods one must embed them in a framework in which four spatial levels—metropolitan, local jurisdiction, neighborhood, and individual—are interconnected in mutually causal ways.

Figure 1.3. A holistic, multilevel, circular causation model of neighborhoods

Previously, I explained the interconnections symbolized by paths A, B, and C in the context of figure 1.2. Aggregate population and physical characteristics of all neighborhoods in a local political jurisdiction will collectively affect what kinds of services and public institutions are demanded (parks, schools, safety forces, etc.), as well as the base of property, income, sales and other potential local taxes that can financially support such services and institutions (path D). Conversely, the combined tax/service package that the local jurisdiction provides to its citizens affects tautologically the quality of housing and the broader social characteristics of its constituent neighborhoods (path E). Finally, individual households and dwelling owners are interconnected with the metropolitan-wide housing market. As housing demanders and suppliers taken together, they “make the market” (path F); market signals in turn shape the mobility, tenure, and investment decisions of these individuals (path G). I amplify the analysis of these connections in chapters 3 and 4.

The Plan, Purposes and Propositions of This Book

I have organized this book to answer fundamental questions regarding neighborhoods in a coherent, cumulative manner. Chapter 2 addresses what a neighborhood is, whether it has definitive boundaries, and whether the “degree of neighborhood” can be measured. Chapters 3 and 4 address what drives changes in a neighborhood’s housing and physical conditions, residents’ economic standing or racial/ethnic (“racial” hereafter) composition, and retail activities. Chapter 5 addresses the question of how households and property owners acquire neighborhood-related information, form expectations about neighborhood change and interact with each other. Chapter 6 addresses the question of whether neighborhood change processes transpire in idiosyncratic, nonlinear ways. Chapter 7 addresses why we have so many blighted neighborhoods and ones that evince little diversity on racial or economic grounds. Chapter 8 addresses the mechanisms through which neighborhoods affect their residents. Chapter 9 addresses the consequences for human and financial capital that transpire when neighborhoods exhibit certain characteristics and change in particular ways, and addresses who disproportionately bears the costs associated with neighborhood processes. It also examines whether the current constellation of American neighborhoods is optimal from society-wide perspectives of efficiency and equity.

This book’s first major purpose is to develop analytical frameworks and marshal evidence from across the social sciences that permit the reader to understand better the origins, nature, and consequences of neighborhood conditions and their dynamics. To this end, I advance eight core propositions related to how we make our neighborhoods and how they make us. These propositions also could be considered testable hypotheses.

- • Externally generated change: Most forces causing neighborhoods to change originate outside the boundaries of that neighborhood, often elsewhere in the metropolitan area.

- • Asymmetric informational power: Information about the absolute decline of the current neighborhood will prove more powerful in altering residents’ and owners’ mobility and investment behaviors than information about its relative decline or its absolute improvement.

- • Racially encoded signals: Key types of information shaping perceptions and expectations about the neighborhood will influence the behaviors of residents and property owners, and a significant amount of such information lies encoded within the share of the black population in the neighborhood.

- • Linked threshold effects: Individual mobility and housing investment decisions are triggered discontinuously once perceptions and expectations regarding the neighborhood have exceeded critical values. Aggregations of individual actions typically lead to large changes in neighborhood conditions only after these causal forces exceed a critical point. Once begun, aggregate changes in neighborhood conditions progress over time in a nonlinear fashion once they exceed another critical point. Many effects of neighborhood conditions on residents and property values only occur once critical values of conditions are exceeded, but eventually the marginal impacts of these conditions may wane at extreme values.

- • Inefficiency: Decision makers in neighborhoods usually undertake an inefficient amount of activities of various sorts due to externalities, strategic gaming, and self-fulfilling prophecies. Externalities: Most decisions in neighborhoods regarding mobility, property upkeep, and so on have impacts on neighbors that typically are not considered by the decision makers. Gaming: Expected payoffs perceived by some decision makers will be influenced by uncertain actions of other decision makers in the neighborhood. Self-fulfilling prophecies: If many individual decision makers share the same expectations about the neighborhood, they will behave collectively in a manner that brings about their expectation.

- • Inequity: Lower-socioeconomic-status households and property owners typically bear a disproportionate share of the financial and social costs of neighborhood changes while reaping comparatively little of their benefits.

- • Multifaceted effect mechanisms: Neighborhood context affects the attitudes, perceptions, behaviors, health, quality of life, and financial well-being of resident adults and children through a variety of causal processes.

- • Unequal opportunity: Because neighborhood context powerfully affects children’s development while neighborhood contexts are very unequal across economic and ethnic groups, space becomes a way of perpetuating unequal opportunities for social advancement.

This book’s second major purpose is to show why and how we should make a more desirable palette of neighborhoods in American metropolitan areas. Based on diagnostic analyses culminating in the eight propositions above, the book builds a prima facie case that strategically targeted public policy interventions are required to make our neighborhoods more fair, humane, and productive environments for all Americans. Chapter 10 provides both overarching principles for strategic targeting interventions and specific prescriptions for public policy and planning initiatives dealing with the three most significant problems associated with how we have made our neighborhoods: physical blight, economic segregation, and racial segregation. It argues for programs that rely on voluntary but incentivized behaviors that gradually move toward a future of “opportunity neighborhoods”: places of good physical quality, safety, diversity in economic and racial dimensions, and resources supplied by public, for-profit, and nonprofit institutions. Such neighborhoods could restore reality to the American promise of “equal opportunity,” and serve as delivery systems for a new model of antipoverty policy and urban economic development.